Data universalism

Data universalism is an epistemological framework that assumes a single universal narrative of any dataset without any consideration of geographical borders and social contexts. This assumption is enabled by a generalized approach in data collection. Data are used in universal endeavours across social, political, and physical sciences unrestricted from their local source and people.[1] Data are gathered and transformed into a mutual understanding of knowing the world which forms theories of knowledge. One of many fields of critical data studies explores the geologies and histories of data by investigating data assemblages and tracing data lineage which unfolds data histories and geographies (p.35).[1] This reveals intersections of data politics, praxes, and powers at play which challenges data universalism as a misguided concept. [1]

Theoretical framework

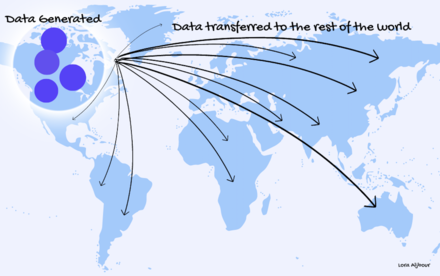

[edit]Data are mainly sampled in rich Western countries which are considered the leaders and voices of technological developments while ignoring cultures, communities, and geographies despite its application being widespread.[2] As the data lifecycle grows, processed small data that are grounded within big data are compiled and formed from heterogeneous sources extracted from mainstream places, forming what has come to be understood as knowledge.[1]

As of 2022, research has not shown the origin behind universalism as a practice due to a lack of controlled data. According to cultural psychologists, democracy and universalism have a positive correlation but there are no studies that show how universalism is shaped by people's experiences and environments (p.1).[3] A push toward datafication has been spurred by democratically advanced Western voices and diffused across fragile democracies in the Global South with no consideration to the geopolitical context and influence powers of the data landscape in countries outside the West.[2] As mentioned by Cappelen et. al, obscure information is found on the epistemology of universalism, although it is argued that a lack of representative data are problematic for broad global analyses (p.1).[3]

Criticism

[edit]

Data universalism has been critiqued by many scholars concerned about data privacy and data justice, claiming that it conceals cultural specifications and diversity. Datafication ought to be viewed through the lens of epistemic diversity and justice to achieve data obedience. So, people are encouraged to critically examine the impacts of datafication by reimagining people and places. [2]

De-westernization

[edit]Milan and Treré have contended that datafication as a privileged practice carried by dominant Western democracies that fail to see the richness of worldviews and meanings of the South. As promoted by Global South and Indigenous scholars, data universalism mistakenly assumes data to be universal when it ought to be treated differently (p.323).[2] If data are extracted without an ethical foundation grounded by attitude and method, the data becomes pervasive and incompetent.[4] Moreover, a shift from a technocentric perspective that emphasizes the human agency behind data to a data method that stimulate discussion about the repercussions of datafication requires relocating the agency. This reinforces the notions of ethics and responsibilities around the data (p.327).[2] A push for bottom-up data practices shifts the focus of datafication to data justice to encourage citizens of the South to participate in political agency and repel an oppressed and inequal datafication process. Negligence in abstracting knowledge from others through diversifying social and historical contexts will result in biased sampling techniques and methods in data generation.[2] This causes skewed data to be generated leading to unequal datafication.[1]

Also, an aggregate technique used for data processing misrepresents data in a way that shapes an aggregate value as representing an aggregated individual. This adheres to the bias factor in making the subject appear as a collective by reducing variance and limiting space of contributions (p.192).[1] Using an aggregate technique submits to universal normativity which situates what is considered to be universally right as a practice that does not take responsibility for the context of a specific situation nor the interpretation of norms. Similarly, the interpretation of norms are also subject to contextual interpretations. While humans operate in unique cases where information can be incomplete, agency empowers humans to assess the situation and make radical decisions in complex situations where information is obscure. Thus, assuming universal normativity will not only incapacitate one's ethical validity when making choices but may lead to questionable decisions (p.284). [4]

Global South

[edit]Historical processes of global capitalism and colonialism have majorly impacted the supply of knowledge from Western modernity and subordinated knowledge from the Global South. Colonialism, in this perspective, is understood as data colonialism which pressures but also exploits datafication on communities. Global South and Indigenous scholars claim that the decolonial lens which transcends to a Eurocentric perspective adds value to critical data studies by questioning the geopolitics of knowledge, the depth of knowledge regeneration, and the power constructions of past injustices. [2] Notions of data politics and data justice are more interested in giving a voice to the underprivileged and acquiring decolonial practices rather than issues concerning the blueprints of the political and social contexts of liberal democracies and social orders. Still, achieving decolonial critical data studies comes with a unique set of challenges that confronts the knowledge that has been produced and the knowings of the world, which is at the center of epistemology. [1] The wave of the big data revolution feeds on insights into the production of data, how knowledge is produced, and how it is conducted and governed while using new epistemologies to make sense of the world.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Kitchin, Rob (2021). The data revolution : a critical analysis of big data, open data & data infrastructures (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-5297-3375-4. OCLC 1285687714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Milan, Stefania; Treré, Emiliano (2019). "Big Data from the South(s): Beyond Data Universalism". Television & New Media. 20 (4): 319–335. doi:10.1177/1527476419837739. hdl:11245.1/e1c07958-9584-4d24-8aba-360688e13fe6. ISSN 1527-4764. S2CID 150586372.

- ^ a b Cappelen, Alexander; Enke, Benjamin; Tungodden, Bertil (2022). Moral Universalism: Global Evidence (Report). National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers. Cambridge, MA. doi:10.3386/w30157. hdl:10419/267342. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ a b Zanotti, Laura (2015). "Questioning universalism, devising an ethics without foundations: An exploration of international relations ontologies and epistemologies". Journal of International Political Theory. 11 (3): 277–295. doi:10.1177/1755088214555044. ISSN 1755-0882. S2CID 146949853.

- ^ Kitchin, Rob (2014-04-01). "Big Data, new epistemologies and paradigm shifts". Big Data & Society. 1 (1): 319–322. doi:10.1177/2053951714528481. ISSN 2053-9517. S2CID 145597078.