Cultural references to Macbeth

The tragic play Macbeth by William Shakespeare has appeared and been reinterpreted in many forms of art and culture since it was written in the early 17th century.

Plays

[edit]The following list of plays including references to Macbeth is ordered alphabetically.

- Wale Ogunyemi's adaptation, A'are Akogun, was first performed in Nigeria in 1968 and mixed the English and Yoruba languages.[1]

- Eugène Ionesco's Macbett satirized Macbeth as a meaningless succession of treachery and slaughter.[2]

- Erica Schmidt's Mac Beth tells the story of seven schoolgirls who perform Macbeth in their free time, which leads to their murder of a classmate.[3][4]

- Macbitches by Sophie McIntosh examines female ambition through the lens of college students surprised at the casting of a freshman as Lady Macbeth.[5][4][6]

- Joe de Graft adapted Macbeth as a battle to take over a powerful corporation in Ghana in his 1972 Mambo or Let's Play Games, My Husband.[7]

- In 2000, Chuck Mike and the Nigerian Performance Studio Workshop produced Mukbutu as a direct commentary on the fragile nature of Nigerian democracy at the time.[8]

- Peerless, a 2022 play written by Jiehae Park, reimagines Macbeth from the perspective of twin Asian-American students competing for admission at a top college.[4][9]

- Maurice Baring's 1911 The Rehearsal fictionalizes Shakespeare's company's inept rehearsals for Macbeth's premiere.[10]

- Sleep No More is an immersive theater experience that loosely adapts Macbeth in a 1930's setting, with additional inspiration taken from the films of Alfred Hitchcock and the 1697 Paisley witch trials.[11]

- Welcome Msomi's 1970 play Umabatha adapts Macbeth to Zulu culture, and was said by The Independent to be "more authentic than any modern Macbeth" in presenting a world in which a man's fighting ability is central to his identity.[12]

- Gu Wuwei's 1916 play The Usurper of State Power adapted both Macbeth and Hamlet as a parody of contemporary events in China.[13]

- Dev Virahsawmy's Zeneral Macbeff, first performed in 1982, adapted the story to the local Creole and to the Mauritian political situation.[14] He later translated Macbeth itself into Mauritian creole, as Trazedji Makbess.[15]

Film

[edit]Joe MacBeth (Ken Hughes, 1955) established the tradition of resetting the Macbeth story among 20th-century gangsters.[16] Others to do so include Men of Respect (William Reilly, 1991),[17] Maqbool (Vishal Bhardwaj, 2003)[18] and Geoffrey Wright's Australian 2006 Macbeth.[19]

In 1957, Akira Kurosawa used the Macbeth story as the basis for the "universally acclaimed"[20] Kumunosu-jo (in English known as Throne of Blood or (the literal translation of its title) Spiderweb Castle).[21] The film is a Japanese period-piece (jidai-geki), drawing upon elements of Noh theatre, especially in its depiction of the evil spirit who takes the part of Shakespeare's witches, and of Asaji, the Lady Macbeth character, played by Isuzu Yamada,[22] and upon Kabuki Theatre in its depiction of Washizu, the Macbeth character, played by Toshiro Mifune.[23] In a twist on Shakespeare's ending, the tyrant (having witnessed Spiderweb Forest come to Spiderweb Castle) is killed by volleys of arrows from his own archers after they come to the realization he also lied about the identity of their former master's murderer.[24]

William Reilly's 1991 Men of Respect, another film to set the Macbeth story among gangsters, has been praised for its accuracy in depicting Mafia rituals, said to be more authentic than those in The Godfather or GoodFellas. However the film failed to please audiences or critics: Leonard Maltin found it "pretentious" and "unintentionally comic" and Daniel Rosenthal describes it as "providing the most risible chunks of modernised Shakespeare in screen history."[25] In 1992 S4C produced a cel-animated Macbeth for the series Shakespeare: The Animated Tales,[26] and in 1997 Jeremy Freeston directed Jason Connery and Helen Baxendale in a low budget, fairly full-text, version.[27]

Twenty-first century

[edit]Twenty-first-century cinema has re-interpreted Macbeth, relocating "Scotland" elsewhere: Maqbool to Mumbai, Scotland, PA to Pennsylvania, Geoffrey Wright's Macbeth to Melbourne, and Allison L. LiCalsi's 2001 Macbeth: The Comedy to a location only differentiated from the reality of New Jersey, where it was filmed, through signifiers such as tartan, Scottish flags and bagpipes.[28] Alexander Abela's 2001 Makibefo was set among, and starred, residents of Faux Cap, a remote fishing community in Madagascar.[29] Leonardo Henriquez' 2000 Sangrador (in English: Bleeder) set the story among Venezuelan bandits and presented a shockingly visualised horror version.[30]

Billy Morrissette's Scotland, PA reframes the Macbeth story as a comedy-thriller set in a 1975 fast-food restaurant, and features James LeGros in the Macbeth role and Maura Tierney as Pat, the Lady Macbeth character: "We're not bad people, Mac. We're just under-achievers who have to make up for lost time." Christopher Walken plays vegetarian detective Ernie McDuff who (in the words of Daniel Rosenthal) "[applies] his uniquely offbeat menacing delivery to innocuous lines."[31] Scotland, PA's conceit of resetting the Macbeth story at a restaurant was followed in BBC Television's 2005 ShakespeaRe-Told adaptation.[32]

Vishal Bhardwaj's 2003 Maqbool, filmed in Hindi and Urdu and set in the Mumbai underworld, was produced in the Bollywood tradition, but heavily influenced by Macbeth, by Francis Ford Coppola's 1972 The Godfather and by Luc Besson's 1994 Léon.[33] It deviates from the Macbeth story in making the Macbeth character (Miyan Maqbool, played by Irfan Khan) a single man, lusting after the mistress (Nimmi, played by Tabbu) of the Duncan character (Jahangir Khan, known as Abbaji, played by Pankaj Kapoor).[18] Another deviation is the comparative delay in the murder: Shakespeare's protagonists murder Duncan early in the play, but more than half of the film has passed by the time Nimmi and Miyan kill Abbaji.[34]

In 2006, Geoffrey Wright directed a Shakespearean-language, extremely violent Macbeth set in the Melbourne underworld. Sam Worthington played Macbeth. Victoria Hill played Lady Macbeth and shared the screenplay credits with Wright.[19] The director considered her portrayal of Lady Macbeth to be the most sympathetic he had ever seen.[35] In spite of the high level of violence and nudity (Macbeth has sex with the three naked schoolgirl witches as they prophesy his fate), intended to appeal to the young audiences that had flocked to Romeo + Juliet, the film flopped at the box office.[36]

The 2011 short film Born Villain, directed by Shia LaBeouf and starring Marilyn Manson, was inspired by Macbeth and features multiple scenes where characters quote from it.

In 2014, Classic Alice wove a 10 episode arc placing its characters in the world of Macbeth. The adaptation uses students and a modern-day setting to loosely parallel Shakespeare's play. It starred Kate Hackett, Chris O'Brien, Elise Cantu and Tony Noto and embarked on an LGBTQ plotline.

The 2015 American black and white film, Thane of East County, features actors in a production of Macbeth who mimic the characters they portray.[37]

Also in 2015, Brazilian film A Floresta que se Move (The Moving Forest) premiered at the Montreal World Film Festival.[38] Directed by Vinícius Coimbra and starred by Gabriel Braga Nunes and Ana Paula Arósio, the film uses a modern-day setting, replacing the throne of Scotland with the presidency of a high-ranked bank.[39][40][41]

The 2016 Malayalam-language film Veeram directed by Jayaraj is an adaptation of Shakespeare's Macbeth[42]

The 2021 Malayalam-language film Joji directed by Dileesh Pothan is a loose adaptation of Shakespeare's Macbeth.[43]

The 2021 Bengali web-series Mandaar on Hoichoi, directed by Anirban Bhattacharya and starring Debasish Mondal and Sohini Sarkar, is a loose adaptation of Shakespeare's Macbeth.[44]

Literature

[edit]There have been numerous literary adaptations and spin-offs from Macbeth. Russian novelist Nikolay Leskov told a variation of the story from Lady Macbeth's point of view in Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which itself became a number of films[45] and an opera by Shostakovich.[46] The play has been used as a background for detective fiction (as in Marvin Kaye's 1976 Bullets for Macbeth)[47] and, in the case of Ngaio Marsh's last detective novel Light Thickens, the play takes centre stage as the rehearsal, production and run of a 'flawless' production is described in absorbing detail (so much so that her biographer describes the novel as effectively Marsh's third production of the play).[48] But the play was also used as the basis of James Thurber's parody of the whodunit genre The Macbeth Murder Mystery, in which the protagonist reads Macbeth applying the conventions of detective stories, and concludes that it must have been Macduff who murdered Duncan.[49] Comics and graphic novels have utilised the play, or have dramatised the circumstances of its inception: Superman himself wrote the play for Shakespeare in the course of one night, in the 1947 Shakespeare's Ghost Writer.[50] A cyberpunk version of Macbeth titled Mac appears in the collection Sound & Fury: Shakespeare Goes Punk.[51] Terry Pratchett reimagined Macbeth in the Discworld novel Wyrd Sisters (1988). In this story 3 witches, led by Granny Weatherwax, attempt to put a murdered king's heir on the throne.[52] In 2018, Jo Nesbø wrote Macbeth, a retelling of the play as a thriller. The novel was part of Hogarth Shakespeare.[53][54]

Lines from the play have inspired titles of many works of literature, for example Agatha Christie's By the Pricking of My Thumbs.[55]: 164 The title of the book comes from Act 4, Scene 1 of Macbeth, when the second witch says:

By the pricking of my thumbs,

Something wicked this way comes.

In Tripp Ainsworth's novel Six Pistols and a Dagger, Smokepit Fairytales Part VI, the events of Macbeth are meshed with those of Blackbeard as the wife of a feared space pirate initiates his downfall.

Eleanor Catton's 2023 novel Birnam Wood takes its title from the play. In the context of the novel, Birnam Wood refers to a "guerrilla gardening collective that... cultivates wherever it can."[56]

Music and audio

[edit]

Macbeth is, with The Tempest, one of the two most-performed Shakespeare plays on BBC Radio, with over 20 productions between 1923 and 2022,[57] the 2022 production starring David Tennant.[58] Other BBC Radio productions include:

- 1934 - Charles Laughton[59]

- 1944 - Leslie Banks[60]

- 1947 - Howard Marion-Crawford[61]

- 1956 - Michael Hordern[62]

- 1966 - Paul Scofield[63]

- 1971 - Joss Ackland[64]

- 1984 - Denis Quilley[65]

- 1991 - Ian Holm

- 1991 - Tim McInnerny[66]

- 1995 - Steven Berkoff[67]

- 2000 - Ken Stott[68]

- 2015 - Neil Dudgeon[69]

One of the best-known recorded productions, starring Anthony Quayle and Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, was released as part of the Shakespeare Recording Society unabridged productions in 1960 by Caedmon Records (SRS-M-231). Other unabridged recorded productions have been released by the Marlowe Society (Argo Records ZPR 201-3), the Old Vic Company (HMV ALP 1176) with Alec Guinness and Pamela Brown, and the Complete Arkangel Shakespeare with Hugh Ross and Harriet Walter

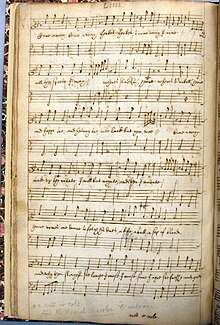

The extant version of Macbeth, in the First Folio, contains dancing and music, including the song "Come Away Hecate" which exists in two collections of lute music (both c.1630, one of them being Drexel 4175) arranged by Robert Johnson.[70] And, from the Restoration onwards, incidental music has frequently been composed for the play: including works by William Boyce in the eighteenth century.[71] Davenant's use of dance in the witches' scenes was inherited by Garrick, which in turn influenced Giuseppe Verdi to incorporate a ballet around the witches' cauldron into his opera Macbeth.[72] Verdi's first Shakespeare-influenced opera, with libretto by Francesco Maria Piave, incorporated a number of striking arias for Lady Macbeth, giving her a prominence in the early part of the play which contrasts with the character's increasing isolation as the action continues: she ceases to sing duets and her sleepwalking confession is starkly contrasted with the "supported grief" of Macduff in the preceding scene.[73] Other music influenced by the play includes Richard Strauss's 1890 symphonic poem Macbeth.[74] Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn incorporated themes depicting the female characters from Macbeth in the 1957 Shakespearean jazz suite Such Sweet Thunder: the weird sisters juxtaposed with Iago (from Othello), and Lady Mac represented by ragtime piano because, as Ellington put it, "we suspect there was a little ragtime in her soul".[75] Another Jazz collaboration to create hybrids of Shakespeare plays was that of Cleo Laine with Johnny Dankworth, who in Laine's 1964 Shakespeare and All That Jazz juxtaposed Titania's instructions to her fairies from A Midsummer Night's Dream with the witches' chant from Macbeth.[76] In 2000, Jag Panzer produced their heavy metal concept-album retelling Thane to the Throne.[77] In 2017, pianist John Burke scored an outdoor production of Macbeth.[78]

In the musical Hamilton by Lin-Manuel Miranda several characters and a direct quote from the second line of Macbeth's Act 5 soliloquy ("Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow...") are referenced in the song "Take a Break." The titular character also states his enemies see him as Macbeth, grabbing power for power's sake.[79]

Visual arts

[edit]The play has inspired numerous works of art. In 1750 and 1760 respectively, the painters John Wootton and Francesco Zuccarelli portrayed Macbeth and Banquo meeting the Three Witches in a scenic landscape, both likely having been inspired by Gaspard Dughet's 1653–4 painting Landscape in a Storm. While Wootton's extended visualization was ultimately more significant, Zuccarelli's allegorical version became available to a much wider constituency, through its 1767 exhibition with the Society of Artists and its subsequent engraving by William Woollett in 1770.[80] The scene in which Lady Macbeth seizes the daggers, as performed by Garrick and Mrs. Pritchard, was a touchstone throughout Henry Fuseli's career, including works in 1766, 1774 and 1812.[81] The same performance was the subject of Johann Zoffany's painting of the Macbeths in 1768.[82] In 1786, John Boydell announced his intention to found his Shakespeare Gallery. His chief innovation was to see the works of Shakespeare as history, rather than contemporary, so instead of including the (then fashionable) works depicting the great actors of the day on stage in modern dress, he commissioned works depicting the action of the plays.[83] However the most notable works in the collection disregard this historicising principle: such as Fuseli's depiction of the naked and heroic Macbeth encountering the witches.[84] William Blake's paintings were also influenced by Shakespeare, including his Pity, inspired by Macbeth's "Pity, like a naked new-born babe, striding the blast."[85] Sarah Siddons' triumph in the role of Lady Macbeth led Joshua Reynolds to depict her as The Muse of Tragedy.[86]

-

John Wootton's 1750 Macbeth and Banquo meeting the Weird Sisters.[87]

-

Francesco Zuccarelli's 1760 rendition of Macbeth and the Witches.[88]

-

James Caldwell's engraving, after Henry Fuseli, of Macbeth's encounter with the witches.[84]

-

Pity by William Blake, based on Macbeth's "Pity, like a naked new-born babe, striding the blast."[85]

-

Joshua Reynolds depicted Sarah Siddons as The Muse of Tragedy, largely due to her triumph in the role of Lady Macbeth.[86]

-

John Singer Sargent's painting of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, in a gown decorated with green beetle wings.[91]

-

The "MacBeth Chair" on display in the Special Collections Department of Cleveland Public Library. The plate affixed to the chair identifies it as being crafted from "Burnam Wood" oak, and it is inscribed with "Fear not till Birnam Wood do come to Dunsinane." (Act V, Scene 5, line 2405–6)

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]Unless otherwise specified, all citations of Macbeth refer to Muir (1984), and of other works of Shakespeare refer to Wells and Taylor (2005).

- ^ Banham (2002, 292)

- ^ Hortmann (2002, 219)

- ^ Collins-Hughes, Laura (May 20, 2019). "Review: Girls Just Wanna Play 'Mac Beth'". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Tran, Diep (Nov 4, 2022). "How Female Playwrights Are Adapting, and Revamping, 'Macbeth'". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "macbitches". Theatrical Rights Worldwide. Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ Ramírez, Juan A. (August 22, 2022). "Review: Without Bloodshed, the Ingénue Takes the Lead". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Banham (2002, 296)

- ^ Banham (2002, 297)

- ^ "peerless". Playbill. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Lanier (2002, 119)

- ^ Brantley, Ben (April 13, 2011). "Shakespeare Slept Here, Albeit Fitfully". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Banham (2002, 286–287), citing The Independent 8 August 1997

- ^ Gillies (2002, 267)

- ^ Banham (2002, 289–292)

- ^ Banham (2002, 289)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 100–102)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 110–111)

- ^ a b Rosenthal (2007, 123–124)

- ^ a b Rosenthal (2007, 127–128)

- ^ Guntner (2000, 125)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 103)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 103–104)

- ^ Howard (2003, 617)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 105)

- ^ Brode (2001, 193); Rosenthal (2007, 110)

- ^ Holland (2007, 43)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 112–3)

- ^ Jess-Cooke (2006, 174–175)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 114–117)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 118–120)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 121–122)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 122)

- ^ Jess-Cooke (2006, 177–178)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 124)

- ^ Interview with Geoffrey Wright in "Making of Documentary" on DVD of Macbeth (2006 film)

- ^ Rosenthal (2007, 127)

- ^ Coddon, David L. (2014-08-20). "San Diego filmmakers mine 'Macbeth' for 'Thane of East County'". San Diego CityBeat. Archived from the original on 2014-09-09. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "A Floresta que se Move / The Moving Forest". Montreal World Film Festival webpage. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Lynn Colling. "Ana Paula Arósio volta ao cinema em 'A Floresta que se Move', filme dirigido por Vinícius Coimbra". Película Criativa (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Flavia Guerra. "Ana Paula Arósio volta às telas em 'A Floresta que se Move'". O Estado de São Paulo (in Portuguese). Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Flavia Guerra. "Ana Paula Arósio é Lady Macbeth em 'A Floresta que se Move'". Carta Capital (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ "Veeram Movie Review". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Joji' trailer: Fahadh Faasil stars in modern-day 'Macbeth' adaptation". The Hindu. 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Mandaar trailer: Macbeth meets Byomkesh in Anirban Bhattacharya's directorial debut". OTTplay. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Brode (2001, 192)

- ^ Sanders (2007, 156)

- ^ Osborne (2007, 129)

- ^ Margaret Lewis 'Ngaio March: A Life'

- ^ Lanier (2002, 85)

- ^ Lanier (2002, 136–137)

- ^ Sound & Fury: Shakespeare Goes Punk

- ^ Shakespeare, William; Williams, William Proctor (2006). Macbeth. Sourcebooks, Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-4022-2679-3. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Larman, Alexander (1 April 2018). "Macbeth by Jo Nesbø review – something noirish this way comes". The Observer. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Drabelle, Dennis. "Review | Jo Nesbo puts a Nordic chill on 'Macbeth'". Washington Post. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Osborne, Charles (2001). The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie: A Biographical Companion to the Works of Agatha Christie. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-28130-7.

- ^ Garner, Dwight (March 13, 2023). "Guerrilla Gardeners Meet Billionaire Doomsayer. Hurly-Burly Ensues". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Greenhalgh (2007, 186 and footnote 39 on 197)

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Macbeth".

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 8 April 1934.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 27 February 1944.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 14 October 1947.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 2 September 1956.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 22 May 1966.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 25 July 1971.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 23 April 1984.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 16 February 1992.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 28 December 1995.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 10 September 2000.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". 17 May 2015.

- ^ Brooke (2008, 225)

- ^ Sanders (2007, 32)

- ^ Sanders (2007, 60)

- ^ Sanders (2007, 83 & 112–116)

- ^ Sanders (2007, 16)

- ^ Sanders (2007, 17 & 20)

- ^ Macbeth 1.1.10–11; A Midsummer Night's Dream 3.1.154–166); Sanders (2007, 22–23)

- ^ Lanier (2002, 72)

- ^ "MACBETH, Starring Justin Deeley, Slashes Into Serenbe Playhouse". Broadway World Atlanta. 2017-06-06. Retrieved 2016-06-14.

- ^ "Take a Break lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda". Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ Sillars (2006, 1–2, 77–79)

- ^ a b Orgel (2007, 74)

- ^ Orgel (2002, 247–249)

- ^ Orgel (2007, 75)

- ^ a b Orgel (2007, 76)

- ^ a b Macbeth 1.7.21–22; Orgel (2007, 77)

- ^ a b Gay, Penny. "Women and Shakespearean Performance", in Wells and Stanton (2002, 155–173) p159.

- ^ Sillars (2006, 158)

- ^ Sillars (2006, 77)

- ^ Orgel (2002, 248)

- ^ Orgel (2007, 74); Orgel (2002, 246–247)

- ^ Schoch (2002,59)

References

[edit]- Bald, Robert Cecil (1928). "Macbeth and the "Short" Plays". The Review of English Studies. os–IV (16). Oxford University Press: 429–31. doi:10.1093/res/os-IV.16.429. ISSN 1471-6968.

- Banham, Martin; Mooneeram, Roshni and Plastow, Jane Shakespeare and Africa in Wells and Stanton (2002, 284–299)

- Barnet, Sylvan (1998). "Macbeth on Stage and Screen". In Barnet, Sylvan (ed.). Macbeth. Signet Classics. New American Library. pp. 186–200. ISBN 978-0451524447.

- Bentley, Gerald Eades (1941). The Jacobean and Caroline Stage. Vol. 6. Clarendon Press.

- Billington, Michael Shakespeare and the Modern British Theatre in Wells and Orlin (2003, 595–606)

- Bloom, Harold (1999). Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. Penguin. ISBN 1-57322-751-X.

- Bloom, Harold (2008). Introduction. In Macbeth: Bloom's Shakespeare Through the Ages. Ed. Harold Bloom. New York: Chelsea House. ISBN 978-0791098424.

- Booth, Michael R. (1995) "Nineteenth-Century Theatre" in Brown (1995, 299–340)

- Braunmuller, Albert R. (1997). "Introduction". In Braunmuller, Albert R. (ed.). Macbeth. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–93. ISBN 0-521-22340-7.

- Brode, Douglas (2001). Shakespeare at the Movies: From the Silent Era to Today. Berkley Boulevard.

- Brooke, Nicholas, ed. (1990). The Tragedy of Macbeth. By William Shakespeare. The Oxford Shakespeare ser. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199535835.

- Brown, John Russell, ed. (1995). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-285442-9.

- Brown, Langdon (1986). Shakespeare around the Globe: A Guide to Notable Postwar Revivals. Greenwood Press.

- Bryant, J. A. Jr. (1961). Hippolyta's View: Some Christian Aspects of Shakespeare's Plays. University of Kentucky Press. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Burnett, Mark Thornton and Wray, Ramona (eds.) (2006). Screening Shakespeare in the Twenty-First Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2351-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chambers, E. K. (1923). The Elizabethan Stage. Vol. 2. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-811511-3. OCLC 336379.

- Clark, Sandra and Pamela Mason, eds. (2015). Macbeth. By William Shakespeare. Arden Third ser. London: The Arden Shakespeare. ISBN 978-1-9042-7140-6.

- Coddon, Karin S. (1989). "'Unreal Mockery': Unreason and the Problem of Spectacle in Macbeth". ELH. 56 (3). Johns Hopkins University: 485–501. doi:10.2307/2873194. JSTOR 2873194.

- Coursen, Herbert R. (1997). Macbeth: A Guide to the Play. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30047-X.

- Dunning, Brian (7 September 2010). "Skeptoid #222: Toil and Trouble: The Curse of Macbeth". Skeptoid. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- Faires, Robert (13 October 2000). "The curse of the play". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- Forsyth, Neil Shakespeare the Illusionist: Filming the Supernatural in Jackson (2000, 274–294)

- Freedman, Barbara Critical Junctures in Shakespeare Screen History: The Case of Richard III in Jackson (2000, 47–71)

- Garber, Marjorie B. (2008). Profiling Shakespeare. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96446-3.

- Gay, Penny Women and Shakespearean Performance in Wells and Stanton (2002, 155–173)

- Gillies, John; Minami, Ryuta; Li, Ruri and Trivedi, Poonam Shakespeare on the Stages of Asia in Wells and Stanton (2002, 259–283)

- Greenhalgh, Susanne Shakespeare Overheard: Performances, Adaptations and Citations on Radio in Shaughnessy (2007, 175–198).

- Guntner, J. Lawrence Hamlet, Macbeth and King Lear on Film in Jackson (2000, 117–134), especially the section Macbeth: of Kings, Castles and Witches at 123–128.

- Gurr, Andrew. 1992. The Shakespearean Stage 1574-1642. Third ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42240-X.

- Halliday, F. E. (1964). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1965. Penguin.

- Hawkes, Terence Shakespeare's Afterlife: Introduction in Welles and Orlin (2003, 571–581)

- Hodgdon, Barbara and Worthen, W. B. (eds.) (2005). A Companion to Shakespeare and Performance. Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4051-8821-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Holland, Peter Touring Shakespeare in Wells and Stanton (2002, 194–211)

- Holland, Peter Shakespeare Abbreviated in Shaughnessy (2007, 26–45)

- Hortmann, Wilhelm Shakespeare on the Political Stage in the Twentieth Century in Wells and Stanton (2002, 212–229)

- Howard, Tony Shakespeare on Film and Video in Wells and Orlin (2003, 607–619)

- Jackson, Russell, ed. (2000). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63975-1.

- Jess-Cooke, Carolyn Screening the McShakespeare in Post-Millennial Shakespeare Cinema in Burnett and Wray (2006, 163–184).

- Kermode, Frank (1974). "Macbeth". In Evans, C. Blakemore (ed.). The Riverside Shakespeare. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 1307–11. ISBN 0-395-04402-2.

- Kliman, Bernice; Santos, Rick (2005). Latin American Shakespeares. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-8386-4064-8.

- Lanier, Douglas (2002). Shakespeare and Modern Popular Culture. Oxford Shakespeare Topics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-818703-3.

- Marsden, Jean I. "Improving Shakespeare: From the Restoration to Garrick." The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage, Cambridge UP, Cambridge, England, 2002, pp. 21–36.

- Maskell, David W. (1971). "The Transformation of History into Epic: The 'Stuartide' (1611) of Jean de Schelandre". Modern Language Review. 66 (1). Modern Humanities Research Association: 53–65. doi:10.2307/3722467. JSTOR 3722467.

- Mason, Pamela Orson Welles and Filmed Shakespeare in Jackson (2000, 183–198), especially the section Macbeth (1948) at 184–189.

- McKernan, Luke and Terris, Olwen (1994). Walking Shadows: Shakespeare in the National Film and Television Archive. British Film Institute. ISBN 0-85170-486-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McLuskie, Kathleen Shakespeare Goes Slumming: Harlem '37 and Birmingham '97 in Hodgdon & Worthen (2005, 249–266)

- Moody, Jane Romantic Shakespeare in Wells and Stanton (2002, 37–57).

- Morrison, Michael A. Shakespeare in North America in Wells and Stanton (2002, 230–258)

- Muir, Kenneth (1984) [1951]. "Introduction". In Muir, Kenneth (ed.). Macbeth (11 ed.). The Arden Shakespeare, Second Series. pp. xiii–lxv. ISBN 978-1-90-343648-6.

- Nagarajan, S. (1956). "A Note on Banquo". Shakespeare Quarterly. 7 (4). Folger Shakespeare Library: 371–6. doi:10.2307/2866356. JSTOR 2866356.

- O'Connor, Marion Reconstructive Shakespeare: Reproducing Elizabethan and Jacobean Stages in Wells and Stanton (2002, 76–97)

- Orgel, Stephen (2002). The Authentic Shakespeare. Routledge. ISBN 041591213X.

- Orgel, Stephen Shakespeare Illustrated in Shaughnessy (2007, 67–92)

- Osborne, Laurie Narration and Staging in Hamlet and its Afternovels in Shaughnessy (2007, 114–133)

- Palmer, J. Foster (1886). "The Celt in Power: Tudor and Cromwell". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 3 (3). Royal Historical Society: 343–70. doi:10.2307/3677851. JSTOR 3677851. S2CID 162969426.

- Paul, Henry Neill (1950). The Royal Play of Macbeth: When, Why, and How It Was Written by Shakespeare. Macmillan Publishers.

- Perkins, William (1618). A Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft, So Farre forth as it is revealed in the Scriptures, and manifest by true experience. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- Potter, Lois Shakespeare in the Theatre, 1660–1900 in Wells and de Grazia (2001, 183–198)

- Rosenthal, Daniel (2007). 100 Shakespeare Films. British Film Institute. ISBN 978-1-84457-170-3.

- Sanders, Julie (2007). Shakespeare and Music: Afterlives and Borrowings. Polity Press. ISBN 978-07456-3297-1.

- Schoch, Richard W. Pictorial Shakespeare in Wells and Stanton (2002, 58–75)

- Shaughnessy, Robert, ed. (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Popular Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60580-9.

- Shirley, Francis (1963). Shakespeare's Use of Off-stage Sounds. University of Nebraska Press.

- Sillars, Stuart (2006). Painting Shakespeare: The Artist as Critic, 1720-1820. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85308-8.

- Smallwood, Robert Twentieth-Century Performance: The Stratford and London Companies in Wells and Stanton (2002, 98–117)

- Spurgeon, Caroline (1969). "Shakespeare's Imagery and What It Tells Us". In Wain, John (ed.). Shakespeare: Macbeth: A Casebook. Casebook Series, AC16. Macmillan. pp. 168–177. ISBN 0-876-95051-9.

- Straczynski, J. Michael (2006). Babylon 5 – The Scripts of J. Michael Straczynski, Vol. 6. Synthetic World.

- Tanitch, Robert (2007). London Stage in the 20th Century. Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904950-74-5.

- Tanitch, Robert (1985). Olivier. Abbeville Press Publishing. ISBN 9780896595903.

- Tatspaugh, Patricia Performance History: Shakespeare on the Stage 1660–2001 in Wells and Orlin (2003, 525–549)

- Taylor, Gary Shakespeare Plays on Renaissance Stages in Wells and Stanton (2002, 1–20)

- Thomson, Peter. 1992. Shakespeare's Theatre. 2nd ed. Theatre Production Studies ser. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-05148-7.

- Tritsch, Dina (April 1984). "The Curse of 'Macbeth'. Is there an evil spell on this ill-starred play?". Showbill. Playbill. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- Walter, Harriet (2002). Actors on Shakespeare: Macbeth. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571214075.

- Wells, Stanley and de Grazia, Margreta (eds.) (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65881-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wells, Stanley and Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.) (2003). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924522-3.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wells, Stanley and Stanton, Sarah (eds.) (2002). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79711-X.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Wells, Stanley; Taylor, Gary; et al., eds. (2005). The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926718-7.

- Wickham, Glynne. (1969). Shakespeare's Dramatic Heritage: Collected Studies in Mediaeval, Tudor and Shakespearean Drama. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-710-06069-6.

- Willems, Michèle Video and its Paradoxes in Jackson (2000, 35–46)

- Williams, Simon The Tragic Actor and Shakespeare in Wells and Stanton (2002, 118–136)

- Zagorin, Perez (1996). "The Historical Significance of Lying and Dissimulation—Truth-Telling, Lying, and Self-Deception". Social Research. 63 (3). The New School for Social Research: 863–912.

External links

[edit]- Performances and Photographs from London and Stratford performances of Macbeth 1960–2000 – From the Designing Shakespeare resource

- Macbeth at the British Library

- Macbeth on Film

- PBS Video directed by Rupert Goold starring Sir Patrick Stewart

- Annotated Text at The Shakespeare Project – annotated HTML version of Macbeth.

- Macbeth Navigator – searchable, annotated HTML version of Macbeth.

Macbeth public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Macbeth public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Macbeth Analysis and Textual Notes

- Annotated Bibliography of Macbeth Criticism

- Macbeth - full annotated text aligned to Common Core Standards

- Shakespeare and the Uses of Power by Steven Greenblatt

- Macbeth

- 1603 plays

- English Renaissance plays

- Regicides

- Plays set in the 11th century

- Plays set in Scotland

- Cultural depictions of Scottish kings

- British plays adapted into films

- Fiction about suicide

- Biographical plays about Scottish royalty

- Fiction about regicide

- Witchcraft in written fiction

- References to literary works

![John Wootton's 1750 Macbeth and Banquo meeting the Weird Sisters.[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/Macbeth_and_Banquo_Meeting_the_Weird_Sisters_JW.jpg/141px-Macbeth_and_Banquo_Meeting_the_Weird_Sisters_JW.jpg)

![Francesco Zuccarelli's 1760 rendition of Macbeth and the Witches.[88]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8b/Macbeth_and_the_Witches.jpg/200px-Macbeth_and_the_Witches.jpg)

![Johann Zoffany's depiction of Hannah Pritchard and David Garrick in Macbeth.[89]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9a/Zoffany-Garrick_and_Pritchard_in_Macbeth.jpg/200px-Zoffany-Garrick_and_Pritchard_in_Macbeth.jpg)

![Henry Fuseli's 1766 depiction of Garrick and Mrs. Pritchard, with the daggers.[90]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/c/c1/Fuseli_Macbeth_1766.jpg/192px-Fuseli_Macbeth_1766.jpg)

![Henry Fuseli's later (1812) reworking of Garrick and Mrs. Pritchard, with the daggers.[81]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Johann_Heinrich_F%C3%BCssli_-_Lady_Macbeth_with_the_Daggers_-_WGA8338.jpg/200px-Johann_Heinrich_F%C3%BCssli_-_Lady_Macbeth_with_the_Daggers_-_WGA8338.jpg)

![James Caldwell's engraving, after Henry Fuseli, of Macbeth's encounter with the witches.[84]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/FuseliMacbethBoydell.jpg/200px-FuseliMacbethBoydell.jpg)

![Pity by William Blake, based on Macbeth's "Pity, like a naked new-born babe, striding the blast."[85]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/Pity_by_William_Blake_1795.jpg/200px-Pity_by_William_Blake_1795.jpg)

![Joshua Reynolds depicted Sarah Siddons as The Muse of Tragedy, largely due to her triumph in the role of Lady Macbeth.[86]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Reynolds%2C_Sir_Joshua_-_Mrs_Siddons_as_the_Tragic_Muse_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/100px-Reynolds%2C_Sir_Joshua_-_Mrs_Siddons_as_the_Tragic_Muse_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

![John Singer Sargent's painting of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, in a gown decorated with green beetle wings.[91]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Ellen_Terry_as_Lady_Macbeth.jpg/84px-Ellen_Terry_as_Lady_Macbeth.jpg)