Joseph Stalin's cult of personality

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-leadership Leader of the Soviet Union Political ideology Works

Legacy  |

||

Joseph Stalin's cult of personality became a prominent feature of Soviet popular culture.[1] Historian Archie Brown sets the celebration of Stalin's 50th birthday on 21 December 1929 as the starting point for his cult of personality.[2] For the rest of Stalin's rule, the Soviet propaganda presented Stalin as an all-powerful, all-knowing leader, with Stalin's name and image displayed all over the country.[3]

Stalin's image in propaganda and the mass media

[edit]

The building of the cult of personality around Stalin had to proceed judiciously, as British historian Ian Kershaw explains in his history of Europe in the first half of the 20th century, To Hell and Back:

A Stalin cult had to be built carefully. This was not just because the man himself was so physically unprepossessing – diminutive and squat, his face dominated by a big walrus mustache and heavily pitted from smallpox – or that he was a secretive, intensely private individual who spoke in a quiet, undemonstrative voice, his Russian couched in a strong Georgian accent that never left him. The real problem was the giant shadow of Lenin. Stalin could not be seen to be usurping the legendary image of the great Bolshevik hero and leader of the revolution. So at first Stalin tread cautiously.[4]

Lenin had not wanted Stalin to succeed him, stating that "Comrade Stalin is too rude" and suggesting that the party find someone "more patient, more loyal, more polite".[5][6] Stalin did not completely succeed in suppressing Lenin's Testament suggesting that others remove Stalin from his position as leader of the Communist party. Nevertheless, after Lenin's death 500,000 copies of a photograph of Lenin and Stalin apparently chatting as friends on a bench appeared throughout the Soviet Union.[6] Before 1932, most Soviet propaganda posters showed Lenin and Stalin together.[7] This propaganda was embraced by Stalin, who made use of their relationship in speeches to the proletariat, stating Lenin was "the great teacher of the proletarians of all nations" and subsequently identifying himself with the proletarians by their kinship as mutual students of Lenin.[8] However, eventually the two figures merged in the Soviet press; Stalin became the embodiment of Lenin. Initially, the press attributed any and all success within the Soviet Union to the wise leadership of both Lenin and Stalin, but eventually Stalin alone became the professed cause of Soviet well-being.[9]

The celebrations for Stalin's 50th birthday in December 1929 marked the real beginning of the construction of the cult around Stalin. Publicly, Stalin was modest, rejecting suggestions that he was Lenin's equal, but allowing a dual celebration of the two men to proceed, before later shifting it primarily to himself. By 1933, central Moscow had twice as many busts and images of Stalin as of Lenin, and Stalin's rare public appearances would trigger ovations lasting 15 minutes or more.[4]

The Soviet press constantly praised Stalin, describing him as "Great", "Beloved", "Bold", "Wise", "Inspirer", and "Genius".[6] It portrayed him as a caring yet strong father figure, with the Soviet populace as his "children".[10] From 1936, the Soviet press started to refer to Stalin as the "Father of Nations",[11] reminding the peasantry of their image of their previous ruler, the tsar, who was seen as a "stern family patriarch". After years of revolutions and civil war, the Russian people longed for strong and purposeful leadership.[12]

Interactions between Stalin and children became a key element of the personality cult. Stalin often engaged in publicized gift giving exchanges with Soviet children from a range of different ethnic backgrounds. Beginning in 1935, the phrase, "Thank You Dear Comrade Stalin for a Happy Childhood!" appeared above doorways at nurseries, orphanages, and schools; children also chanted this slogan at festivals.[13]

Speeches described Stalin as "Our Best Collective Farm Worker", "Our Shockworker, Our Best of Best", and "Our Darling, Our Guiding Star".[6] The image of Stalin as a father was one way in which Soviet propagandists aimed to incorporate traditional religious symbols and language into the cult of personality; the title of "father" now first and foremost belonged to Stalin, as opposed to the Russian Orthodox priests. The cult of personality also adopted the Christian traditions of procession and devotion to icons through the use of Stalinist parades and effigies. By reapplying various aspects of religion to the cult of personality, the press hoped to shift devotion away from the church and towards Stalin.[14]

Initially, the press also aimed to demonstrate a direct link between Stalin and the common people; newspapers often published collective letters from farm or industrial workers praising the leader,[15] as well as accounts and poems about meeting Stalin. Shortly after the revolution of October 1917, Ivan Tovstukha drafted up a biographical section featuring Stalin for the Russian Granat Encyclopedia Dictionary.[16] Even though most of the description of Stalin's career was very much embellished, it had gained so much favor with the public that they released a fourteen-page pamphlet of it alone named Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin: A Short Biography with a print run of 50,000.[17] However, these sorts of accounts declined after World War II; Stalin drew back from public life, and the press instead began to focus on remote contact (i.e. accounts of receiving a telegram from Stalin or seeing the leader from afar).[18] Another prominent part of Stalin's image in the mass media was his close association with Vladimir Lenin. The Soviet press maintained that Stalin had been Lenin's constant companion while the latter was alive, and that as such, Stalin closely followed Lenin's teachings and could continue the Bolshevik legacy after Lenin's death.[19] Stalin fiercely defended the correctness of Lenin's views in public, and in doing so Stalin implied that, as a faithful follower of Leninism, his own leadership was similarly faultless.[20]

Other displays of devotion

[edit]Stalin became the focus of literature, poetry, music, paintings and film that exhibited fawning devotion. An example was Alexander O. Avdeenko's "Hymn to Stalin", which came from an earlier speech made by him in 1935:[21]

Thank you, Stalin. Thank you because I am joyful. Thank you because I am well. No matter how old I become, I shall never forget how we received Stalin two days ago. Centuries will pass, and the generations still to come will regard us as the happiest of mortals, as the most fortunate of men, because we lived in the century of centuries, because we were privileged to see Stalin, our inspired leader ... Everything belongs to thee, chief of our great country. And when the woman I love presents me with a child the first word it shall utter will be : Stalin ...[22]

| Part of a series on |

| Stalinism |

|---|

|

Numerous pictures and statues of Stalin adorned public places. In 1955 a giant monument dedicated to Stalin was constructed in Prague and stood until 1962. The statue was a gift for Stalin's sixty-ninth birthday from Prague to commemorate "Mr. Stalin's personality, mostly from his ideological features".[23] After 5 years in the making, the massive 17,000-ton monument was finally revealed to the public which depicted Stalin, with one at the front of a group of proletarian workers.[24] Statues of Stalin depicted him at a height and build approximating the very tall Tsar Alexander III, but photographic evidence suggests he was between 5 ft 5 in and 5 ft 6 in (165–168 cm). Stalin-themed art appeared privately, as well: starting in the early 1930s, many private homes included "Stalin rooms" dedicated to the leader and featuring his portrait.[25] Although it was not an official uniform, party leaders throughout the Soviet Union emulated the dictator's usual outfit of dark green jacket, riding breeches, boots, and cap to prove their devotion.[6]

The cult also led to public devotional behavior: by the late 1930s, people would jump out of their seats to stand up whenever Stalin's name was uttered in public meetings and conferences. Nikita Khrushchev described it as "a sort of physical culture we all engaged in."[26]

The advent of the cult also led to a renaming craze: numerous towns, villages and cities were renamed after the Soviet leader. The Stalin Prize and Stalin Peace Prize were also named in his honor, and he accepted several grandiloquent titles (e.g., "Father of Nations", "Builder of Socialism", "Architect of Communism", "Leader of Progressive Humanity") among others.

The cult reached new levels during World War II, with Stalin's name included in the new Soviet national anthem.

In December 1949, Stalin celebrated his purported 70th birthday (he had in fact been born in December 1878). His birthday was celebrated extensively throughout the USSR. In the Ukrainian city of Mariupol, the former Sanatorium Avenue was renamed to Stalin Avenue. Various statues and institutions were made to honor him. On 2 December 1949, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree to form a government committee centered on Stalin's birthday. 18 days later, the Supreme Soviet awarded the Order of Lenin to Stalin. On 21 December, the day after he was awarded, a ceremonial meeting dedicated to the 70th birthday of Stalin took place in the Bolshoi Theater.[27] Notable world leaders were in attendance, including Chinese leader Mao Zedong and East German Deputy Prime Minister Walter Ulbricht. Marshal of the Mongolian People's Republic Khorloogiin Choibalsan, who was once a favorite of Stalin, did not attend the ceremonies, instead sending General Secretary Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal. For Mao, the celebrations were part of his first state visit to the USSR since taking power.

In many Eastern bloc countries, Stalin's birthday was also celebrated extensively. The Bulgarian city of Varna was renamed to Stalin and Musala was renamed to Stalin Peak. The Gerlachovský štít in Czechoslovakia was also renamed after Stalin.

Stalin and young people

[edit]

One way Stalin's cult was spread was through the Komsomol, the All-Union Leninist Communist League of Youth in Soviet Russia, created in 1918. The ages of these young people ranged from 9 to 28 years old making it a favorable instrument to reshape the members and ideology of the Soviet Union. This organization was created to raise the next generation into the type of socialist that Stalin envisioned. Being a part of this organization was beneficial to the participants for they were favored over a non-member when it came to getting scholarships and jobs.[28] Just like most youth clubs, they focused on their members' education and health, with sports and physical activities. They also focused on the youths' behavior and character. The children were encouraged to reject anyone who didn't embody the values of a socialist. In cases of lying and cheating on the schoolyard, it resulted to "classroom trials".[29] Stalin wanted the best to prevail in his image of the future Soviet Union so he put into effect a decree that would punish juvenile delinquency to ensure the 'good apples' were the ones paving the road for his ideal society.[30]

Organizations like the Komsomol were not the only influences on the children at the time. Cartoons like The Strangers Voice by Ivan Ivanov-Vano, reinforced the idea of a Soviet culture by depicting foreign thinking and customs as unwanted and strange.[31] Children would play their own version of 'Cowboys and Indians' as 'Reds and Whites' with children fighting to play the main party leaders like Stalin.[29]

Illusion of unanimous support

[edit]The cult of personality primarily existed among the Soviet masses; there was no explicit manifestation of the cult among the members of the Politburo and other high-ranking Party officials. However, the fear of being marginalized made oppositionists sometimes hesitant to honestly express their viewpoints. This atmosphere of self-censorship created the illusion of undisputed government support for Stalin, and this perceived support further fueled the cult for the Soviet populace. The politburo and comintern secretariat (E.C.C.I.) also gave the impression of being unanimous in its decisions although this was often not the case. Many top ranking leaders in the politburo such as Zhdanov and Kaganovich sometimes disagreed with Stalin. Not all of Stalin's proposals were passed, but this was not made known to people outside the party leadership. The party leadership discussed and debated various alternatives but always presented themselves as monolithic to the outside world to appear stronger, more credible and unified. Among the leadership this was also considered correct Leninist practice, since the Leninist organizational principle of democratic centralism provided "freedom of debate" but required "unity of action" after a decision had been reached. The minority felt it their duty to submit to the will of the majority and Stalin himself practiced this when losing a vote.[32]

Stalin's opinion of his cult

[edit]Like Lenin, Stalin acted modestly and unassumingly in public. John Gunther in 1940 described the politeness and good manners to visitors of "the most powerful single human being in the world".[6] In the 1930s Stalin made several speeches that diminished the importance of individual leaders and disparaged the cult forming around him, painting such a cult as un-Bolshevik; instead, he emphasized the importance of broader social forces, such as the working class.[33][34] Stalin's public actions seemed to support his professed disdain of the cult: Stalin often edited reports of Kremlin receptions, cutting applause and praise aimed at him and adding applause for other Soviet leaders.[33] Walter Duranty stated that Stalin edited a phrase in a draft of an interview by him of the dictator from "inheritor of the mantle of Lenin" to "faithful servant of Lenin".[6]

A banner in 1934 was to feature Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, but Stalin had his name removed from it, yet by 1938 he was more than comfortable with the banner featuring his name.[35] Still, in 1936, Stalin banned renaming places after him.[36] In some memoirs Molotov claimed that Stalin had resisted the cult of personality, but soon came to be comfortable with it.[37]

The Finnish communist Arvo Tuominen reported a sarcastic toast proposed by Stalin himself at a New Year's Party in 1935, in which he said: "Comrades! I want to propose a toast to our patriarch, life and sun, liberator of nations, architect of socialism [he rattled off all the appellations applied to him in those days] – Josef Vissarionovich Stalin, and I hope this is the first and last speech made to that genius this evening."[38] In the beginning of 1938, Nikolai Yezhov proposed renaming Moscow to "Stalinodar".[39] The question was raised at a session of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. Stalin, however, reacted entirely negatively to this idea and, for this reason, the city retained the name Moscow.[39]

Veneration of Stalin by the Soviet people for his role as the leader of the Soviet Union's victory over Nazi Germany in World War II helped to stabilize their belief in the Soviet system, a factor of which Stalin was aware. Historian Archie Brown wrote: "Stalin himself believed that his 'image' ... as a charismatic, almost superhuman, leader helped to solidify support for Communism and to bestow on it legitimacy." It was a constant in Stalin's beliefs that the Russian people, especially the peasants, were used to being ruled by a single person, the tsar, and did not understand the complexities of the structure of power and governance in the Soviet Union. Because of this, there had to be one person who was perceived as the ruler, someone they could, in his words "revere and in whose name to live and labour".[40] In 1940, Gunther noted that "[Stalin] knows the Russians understand a master". The dictator could easily have stopped the adoration but "permitted and encouraged his own virtual deification", he said. "Or perhaps he likes" the worship, Gunther speculated.[6]

However, Stalin discouraged all interest in his private and family life, and divulged only limited personal information.[36] He rarely appeared in public or met with ambassadors, as of 1940 had met only seven foreign journalists for formal interviews in 20 years, and during the first five-year plan made no speeches or public appearances for 18 months.[6]

Nikita Khrushchev in his "Secret Speech" to the 20th Party Congress in February 1956, claimed that Stalin had personally added by hand to the manuscript of the hagiographical Short Biography of Stalin, published in 1948, passages such as: "Although he performed his task as the leader of the party and the people with consummate skill and enjoyed the unreserved support of the entire Soviet people, Stalin never allowed his work to be marred by the slightest hint of vanity, conceit or self-adulation." In addition Khrushchev claimed that Stalin expanded the list of his accomplishments enumerated in the book.[41] Despite this, scholars have cited evidence that cast doubt to Khrushchev's claims. Few scholars today would cite Khrushchev's speech as a reliable source and it now seems clear that Stalin distrusted the cult of personality around him.[citation needed]

Stories of the Childhood of Stalin

[edit]On February 16, 1938, after the release of a book called Stories of the Childhood of Stalin, the publishing committee was urged to retract the book, as Stalin claimed that the book was an example of excessive hero worship that elevated his image to idealistic proportions. Stalin spoke disdainfully of this excess, expressing concern that idolatry is no substitute for rigorous Bolshevik study, and could be spun as a fault of Bolshevism by right-deviations in the USSR.[42] Specifically he wrote:

I am absolutely against the publication of "Stories of the childhood of Stalin". The book abounds with a mass of inexactitudes of fact, of alterations, of exaggerations and of unmerited praise. Some amateur writers, scribblers, (perhaps honest scribblers) and some adulators have led the author astray. It is a shame for the author, but a fact remains a fact. But this is not the important thing. The important thing resides in the fact that the book has a tendency to engrave on the minds of Soviet children (and people in general) the personality cult of leaders, of infallible heroes. This is dangerous and detrimental. The theory of "heroes" and the "crowd" is not a Bolshevik, but a SR theory. The heroes make the people, transform them from a crowd into people, thus say the SRs. The people make the heroes, thus reply the Bolsheviks to the SRs. The book carries water to the windmill of the SRs. No matter which book it is that brings the water to the windmill of the SRs, this book is going to drown in our common, Bolshevik cause. I suggest we burn this book.[43]

A more accurate depiction of his childhood and achievements are found in many other areas of writing and genre.[44]

End of the cult and de-Stalinization

[edit]

De-Stalinization was the process of political reform that took place after Stalin's death, where a majority of Joseph Stalin's actions during his reign were condemned and the government reformed. February 1956 was the beginning of the destruction of his image, leadership, and socialist legality under the thaw of Nikita Khrushchev at the 20th Party Congress.[45][46] The end of Stalin's leadership was met with positive and negative changes. Changes and consequences revolved around politics, the arts and literature, the economic realm, to the social structure.[47]

His death and the destabilization of his iconic leadership was met with the chance of new reforms and changes to his regime that had originally been immediately locked down under his control. The tight lock he kept on what was published, what was propagated, and what changes to the government and economics, became accessible. With the control that Stalin held being passed on to the government, an endorsed methodology was ideally enacted.[48] Thereafter, a collective leadership system was the result. The result left Nikita Khrushchev, Lavrentiy Beria, Nikolai Bulganin, Georgy Malenkov, Vyacheslav Molotov, and Lazar Kaganovich as members of that committee. The program of de-Stalinization was soon after put into effect by Krushchev as he took on an opposite personality into the government. This allowed for better relations with the West in the future.[49]

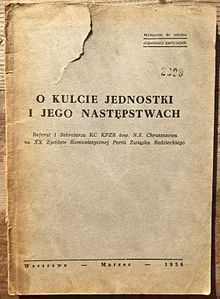

First wave of de-Stalinization

[edit]After Stalin's death, Nikita Khrushchev's 1956 "Secret Speech" to the Twentieth Party Congress famously denounced Stalin's cult of personality, saying, "It is impermissible and foreign to the spirit of Marxism-Leninism to elevate one person, to transform him into a superman possessing supernatural characteristics akin to those of a god."[50] The "Secret Speech" initiated a political reform known as "the overcoming/exposure of the cult of personality",[51] later called de-Stalinization, that sought to eradicate Stalin's influence on the Soviet society. This also led the people to find the liberation to revolt publicly in Poland and Hungary.[49] These changes were inevitably met with opposition. Even after losing favor with Stalin during his leadership, Molotov still argued in favor of Stalin's regime, opposing de-Stalinization and criticizing Stalin's successors.[52] Mao Zedong, along with some other communist leaders, while initially supporting the struggle against the "cult of the individual", criticized Khrushchev as an opportunist who merely sought to attack Stalin's leadership and policies in order to implement new, different policies that in the Stalin era would have been considered anti-Marxist revisionism.[53]

Under Khrushchev's successor, Leonid Brezhnev, pro-Stalinist forces attempted to re-establish Stalin's reputation as the "Great Leader". Having failed to do so at the 23rd Party Congress in the spring of 1966, they turned to another method, the text of a speech that Brezhnev was scheduled to give in November of that year in Georgia, Stalin's native country. A draft of the speech made by hard-core Stalinists was presented to Brezhnev, who, being a cautious man, distributed it to other officials for their comments. One of his advisors, Georgi Arbatov, with the support of his superior, Yuri Andropov, put the arguments against the draft to Brezhnev: rehabilitating Stalin would complicate the Soviet Union's relations with the Eastern European Communist states, especially those headed by men who had been victims of Stalin's actions; changing the status of Stalin once again, so soon after it had been downgraded, would make things difficult for the Western Communist parties; it would be difficult to reconcile the harsh words spoken against Stalin by prominent Communist leaders at the 20th and 22nd Party Congresses; and finally, it was pointed out that Brezhnev himself had participated in those Congresses, which would raise questions about his own role. As a result of these arguments, the speech was re-written without any mention of rehabilitating Stalin. Even though the anti-Stalinists prevailed in this instance, the use of the phrase "the period of the cult of personality" – referring to 1934–1953 – disappeared, indicating a softening of the official anti-Stalin line. Thus, it became easier for pro-Stalin viewpoints to be published, and harder to get anti-Stalin works before the public.[54]

Second wave

[edit]This changed when Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the country's top leadership position. In a speech given in November 1987, on the eve of the celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, Gorbachev said:

It is sometimes asserted that Stalin did not know the facts about the lawlessness. Documents we have at our disposal speak to the fact that this is not so. The guilt of Stalin and of his closest associates before the party and people for indulging in mass repression and lawlessness is enormous and unforgivable. This is a lesson for all generations.[55]

After this, during the period of glasnost ("openness") and perestroika ("restructuring") initiated by Gorbachev, another wave of de-Stalinization took place. This "second wave" evolved into something more fundamentally anti-communist. It condemned not only Stalin but also the other responsible people in the Soviet power hierarchy. In the end, it adopted something closer to a Western democratic structure in place of the traditional closed communist authoritarian system.[56] This campaign aimed to restructure the Soviet Union entirely, engaging public constituencies to diminish communism and bringing an end to the Soviet Union.[56][57]

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation under Vladimir Putin saw a return of both centralized and authoritarian control of the state and the cult of Stalin, focusing primarily on his role in the defeat of Nazi Germany and the winning of World War II.[56] During this period, in the early 2000s, Russia had lost its role as a global superpower, and restoring the positive legacy of Stalin helped to ameliorate the felt loss of status, bringing back a symbol of the country – albeit the Soviet Union predecessor state – at the height of its power.[56][47]

Third wave

[edit]Nevertheless, a "third wave" of more ambivalent de-Stalinization was still able to get off the ground around 2009. This fostered a reassessment of Stalinism as well as commemorating the victims of his totalitarian regime. For instance, Dmitry Medvedev, the president of Russia, said about the Katyn massacre of Polish officers in World War II by the Soviet Army that "Stalin and his henchmen bear responsibility for this crime", echoing a previous statement by the Russian Parliament: "The Katyn crime was committed on direct order by Stalin and other Soviet leaders." Partly driven by Russian re-engagement with the West, the new de-Stalinization, unlike that under Gorbachev, has not been accompanied by liberalization and reform of the political system, which remains centralized, authoritarian, and dependent on the repression of the people by the security police, much as in Stalin's time. Such a paradoxical situation, where Stalin's reputation is downgraded, but the state is essentially following in the path blazed by him, leads to the ambivalence of the official position. On the one hand, Moscow city officials were prevented from putting up decorations featuring Stalin for the celebration of the 65th anniversary of the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany, with Medvedev saying that Stalin had "committed many crimes against his people. And even though the country achieved success under his guidance, what was done against his own people cannot be forgiven." On the other hand, there is no shortage of publications and television programs glorifying Stalin. Anti-Stalin sentiment is not being suppressed, but neither are pro-Stalin views. And despite the official statements of Stalin's culpability, those in power are still anxious to use the symbolic value of the dictator in support of their own monopolistic hold on the country.[opinion][56]

In classrooms across Russia, students are taught out of a modern textbook which represents Stalin as simply an efficient leader who had the unfortunate responsibility to resort to extreme measures to protect Russia and ensure its leadership role on a global scale.[57] A poll in 2019 found that 70% of Russians believed that Stalin had a positive impact on Russian history, while only 51% of people in Russia viewed Stalin with a positive attitude.[58]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gill, "The Soviet Leader Cult", p.167

- ^ Brown 2009, p. 71.

- ^ Gill, Graeme (December 2021). Marquez, Xavier (ed.). "The Stalin Cult as Political Religion". Religions. 12 (12: Religion, Ritual, and Political Leader Cults). Basel: MDPI: 112. doi:10.3390/rel12121112. eISSN 2077-1444.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2016, p. 269.

- ^ Siegelbaum, Lewis (17 June 2015). "Lenin's Succession". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. Harper & Brothers. pp. 516–517, 530–532, 534–535.

- ^ Bonnell, The Iconography of Power, p.158

- ^ "Marxists Internet Archive - Reply to the Greetings of the Workers of the Chief Railway Workshops in Tiflis". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- ^ Gill, "The Soviet Leader Cult", p.169

- ^ Gill, "The Soviet Leader Cult", p.171

- ^ Father of Nations at the Encyclopedic dictionary of catchy words and phrases.

- ^ Kershaw 2016, pp. 269–70.

- ^ Kelly, "Riding the Magic Carpet", pp.206–207

- ^ Bonnell, The Iconography of Power, p.165

- ^ Ennker, Benno (2004) "The Stalin Cult, Bolshevik Rule and Kremlin Interactions in the 1930s", in Apor, Balázs et al. eds. The Leader Cult in Communist Dictatorship: Stalin and the Eastern Bloc. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p.85

- ^ Brandenberger, David (2014). Propaganda State in Crisis: Soviet Ideology, Indoctrination, and Terror Under Stalin, 1927-1941. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300159639.

- ^ Davies, Sarah (2005). Stalin: A New History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 252.

- ^ Kelly, "Riding the Magic Carpet", p.208

- ^ Gill, "The Soviet Leader Cult", p.168

- ^ Tucker, Robert (1990) Stalin in Power: the Revolution From Above, 1929–1941 New York: Norton. p.154

- ^ "Спасибо тебе, товарищ Сталин (Валерий Ефимов) / Проза.ру". proza.ru. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ Avidenko, A. O. Halsall, Paul (ed.). "Hymn to Stalin". Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Fordham University, 1997. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- ^ "Prague Monument for Stalin". New York Times. 19 December 1948. p. 17.

- ^ Shimov, Yaroslav (8 June 2016). "Monster: The Monument That Destroyed Its Creator". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- ^ Kelly, "Riding the Magic Carpet", p.202

- ^ Brown, Archie (2009) The Rise and Fall of Communism New York: HarperCollins. p.61. ISBN 978-0-06-113879-9

- ^ Лев Котюков. Забытый поэт. Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Komsomol | Soviet youth organization". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ^ a b Kenny, Julia (2015-09-18). "Stalin's Cult of Personality: Its Origins and Progression". The York Historian. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ "Life Under Stalin: Childhood or Cult?". 20th Century Russia. 2014-10-13. Archived from the original on 2018-04-23. Retrieved 2018-04-22.

- ^ KristophShmit (2017-03-21), "Stranger's Voice" 1949 Soviet Cartoon, retrieved 2018-04-22

- ^ Arvo Tuominen. Sirpin ja Vasaran Tie.

- ^ a b Davies, "Stalin and the Making of the Leader Cult in the 1930s", pp. 30–31

- ^ Stalin, Joseph (August 1930). "Letter to Comrade Shatunovsky". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

You speak of your 'devotion' to me. Perhaps it was just a chance phrase. Perhaps. But if the phrase was not accidental I would advise you to discard the 'principle' of devotion to persons. It is not the Bolshevik way. Be devoted to the working class, its Party, its state. That is a fine and useful thing. But do not confuse it with devotion to persons, this vain and useless bauble of weak-minded intellectuals.

- ^ Pisch, Anita (2016). "The Personality Cult of Stalin in Soviet Posters, 1929–1953: Archetypes, inventions & fabrications". Australian National University. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Davies, "Stalin and the Making of the Leader Cult in the 1930s", p.41

- ^ Davies, Sarah (2014). Stalin's World: Dictating the Soviet Order. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300182811. OCLC 875644434.

- ^ Tuominen, Arvo (1933). Heiskanen, Piltti (ed.). The Bells of the Kremlin. Translated by Leino, Lily. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. p. 162.

- ^ a b Getty, John Archibald (1994). Stalinist terror: new perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-521-44125-0. OCLC 256629977.

- ^ Brown 2009, p. 196.

- ^ Brown 2009, p. 243.

- ^ "Letter on Publications for Children Directed to the Central Committee of the All Union Communist Youth". Marxists.org. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ Voprosy Istorii(Questions of History)No. 11, 1953

- ^ "Joseph Stalin – Facts & Summary". History.com. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ "De-Stalinization | Soviet history". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ Khrushcheva, Nina L. (2006-02-19). "The day Khrushchev buried Stalin". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2018-04-27.[dead link]

- ^ a b Jones, Polly (2006). The Dilemmas of De-Stalinization: Negotiating Cultural and Social Change in the Khrushchev Era. Routledge. ISBN 1134283466.

- ^ "The rise of the Stalin personality cult". The Personality Cult of Stalin in Soviet Posters, 1929–1953. Australian National University. Retrieved 2024-07-16.

- ^ a b "Nikita Khrushchev – Cold War". History.com. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ Kaganovsky, Lilya (2008). How the Soviet Man Was Unmade. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 146.

- ^ Jones, Polly (2006). The Dilemmas of De-Stalinization: Negotiating Cultural and Social Change in the Khrushchev Era. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-134-28347-7.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (23 April 2018). "Truman confronts Molotov at White House, April 23, 1945". Politico. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ Mao Zedong (July 1964). "On Khrushchov's Phoney Communism and Its Historical Lessons for the World" – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Brown 2009, pp. 400–401.

- ^ Brown 2009, p. 485.

- ^ a b c d e Lipman, Masha (16 December 2010). "The Third Wave of Russian De-Stalinization". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Russia rewriting Josef Stalin's legacy". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- ^ "Stalin's perception". Yuri Levada Analytical Center. 19 April 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bonnell, Victoria E. (1999) The Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin Berkeley, Calaifornia: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52-022153-6

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise and Fall of Communism. New York: ecco (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0-06-113879-9.

- Davies, Sarah (2004) "Stalin and the Making of the Leader Cult in the 1930s", in Apor, Balázs et al. eds. The Leader Cult in Communist Dictatorship: Stalin and the Eastern Bloc, New York: Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-34-951714-5

- Gill, Graeme (1980) "The Soviet Leader Cult: Reflections on the Structure of Leadership in the Soviet Union", British Journal of Political Science v.10

- Kelly, Catriona (2005) "Riding the Magic Carpet: Children and the Leader Cult in the Stalin Era", Slavic and East European Journal v.49

- Kershaw, Ian (2016). To Hell and Back: Europe 1914–1949. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-310992-1.