Columbia, Maryland

Columbia, Maryland | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Downtown Columbia | |

| Motto: "The Next America!"[1] | |

Location of Columbia, Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°12′13″N 76°51′25″W / 39.20361°N 76.85694°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Howard |

| Founded | June 21, 1967[2] |

| Founded by | James Rouse |

| Named for | Columbia (personification) |

| Area | |

• Total | 32.19 sq mi (83.37 km2) |

| • Land | 31.93 sq mi (82.71 km2) |

| • Water | 0.26 sq mi (0.66 km2) |

| Elevation | 407 ft (124 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 104,681 |

| • Density | 3,278.04/sq mi (1,265.68/km2) |

| The CDP includes areas not part of Columbia proper as defined by the Columbia Association. | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 21044-21046 |

| Area codes | 410, 443, 667 |

| FIPS code | 24-19125 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0590002 |

| Website | columbiaassociation.org |

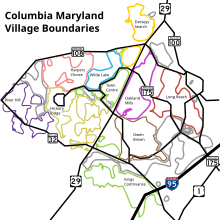

Columbia is a planned community in Howard County, Maryland, United States, consisting of 10 self-contained villages. With a population of 104,681 at the 2020 census, it is the second most populous community in Maryland after Baltimore.[4][5] Columbia, located nearly halfway between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., is part of the Baltimore metropolitan area and is tracked by the United States Census Bureau as a census-designated place. Columbia proper consists only of territory governed by the Columbia Association, but larger areas are included under its name by the Census Bureau and the United States Postal Service. These include several other communities which predate Columbia, including Simpsonville, Atholton, and in the case of the Census, part of Clarksville.

Founded in 1967, Columbia began with the idea that a city could enhance its residents' quality of life. Developer James Rouse attempted to create the new community in terms of human values, rather than economics and engineering. Columbia was intended to not only eliminate the inconveniences of then-current subdivision design, but also eliminate racial, religious and class segregation.[6] Rouse additionally stated that Columbia would help avoid the leap-frog and spot-zoning development threatening the county.[7]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]Prior to the European colonization of what is now Maryland in the 1600s, the area that is now Columbia served as farming and hunting grounds for indigenous peoples including the Piscataway and Susquehannock peoples.[8][9] Columbia was founded by James W. Rouse (1914–1996), a native of Easton, Maryland. In 1935, Rouse obtained a job in Baltimore with the Federal Housing Administration, a New Deal agency whose purpose was to promote home ownership and home construction. This position exposed Rouse to all phases of the housing industry.[10] Later in the 1930s he co-founded a Baltimore mortgage banking business, the Moss-Rouse Company. In the 1950s his company, by then known as James W. Rouse and Company, branched out into developing shopping centers and malls. In 1957, Rouse formed Community Research and Development, Inc. (CRD) for the purpose of building, owning and operating shopping centers throughout the country. Community Research and Development, Inc., which was managed by James W. Rouse and Company, became a publicly traded company in 1961. In 1966, Community Research and Development, Inc. changed its name to The Rouse Company, after it had acquired James W. Rouse and Company in exchange for company stock.[11][12]

By the early 1950s Rouse was also active in organizations whose goals were to combat blight and promote urban renewal. Along the way, he came to recognize the importance of comprehensive planning and action to address housing issues. A talented public speaker, Rouse's speeches on housing matters attracted media attention. By the mid-1950s he was espousing his belief that in order to be successful, cities had to be places where people succeeded. In a 1959 speech he declared that the purpose of cities is for people, and that the objective of city planning should be to make a city into neighborhoods where men, women, and their families can live and work, and, most importantly, grow in character, personality, religious fulfillment, brotherhood, and the capacity for joyous living.[citation needed]

In the early 1960s, Rouse decided to develop a new model city. Rouse's ideas about what a new model city should be like were informed by a number of factors, including his personal Christian faith as well as the goal for his company to earn a profit, influences that he did not consider to be incompatible with one another.[13] After exploring possible new city locations near Atlanta, Georgia, and Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, Rouse focused his attention between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., in Howard County, Maryland.

Howard County land acquisition

[edit]In April 1962, Mel Berman, a longtime Howard County resident who was also a member of the CRD's Board of Directors, saw a sign on Cedar Lane in Howard County advertising 1,309 acres (530 ha) for sale. Berman reported the option to the CRD and a decision was made to purchase the land. This was the first of 165 land purchases made by Rouse over the next year-and-a-half. In order to keep land costs low, Jack Jones, an attorney from Rouse's firm of Piper Marbury, set up a grid system to secretly buy land through dummy corporations like the "Alaska Iron Mines Company".[14][15] Some of these straw purchasers included Columbia Industrial Development Corporation, 95-32 Corporation, 95-216 Corporation, Premble, Inc., Columbia Mall, Inc., Oakland Ridge Industrial Development Corporation, and Columbia Development Corporation. Robert Moxley's firm Security Realty Company (now Security Development Group Inc),[16] negotiated many of the land deals for Jones, becoming his best client.[16][17]: 57 [18] CRD accumulated 14,178 acres (57.38 km2), 10 percent of Howard County, from 140 separate owners. Rouse was turned down in financing from David Rockefeller, who had recently cancelled a planned Rouse "Village" concept called Pocantico Hills.[17]: 58 The $19,122,622 acquisition was then funded by Rouse's former employer Connecticut General Life Insurance in October 1962 at an average price of $1,500 per acre ($0.37/m2). The town center land of Oakland Manor was purchased from Isadore Guldesky who was turned down from building high-rises on the site by Rob Moxley's brother, County Commissioner and land developer Norman E. Moxley. Sensing that he had a key property, he requested $5 million for his 1,000 acres (400 ha), signing an agreement by hand on a land plat.[19] The competition between Rouse and Guldesky carried over to the competing Tysons Corner Center and Tysons Galleria projects, with each hiring their competitor's employees.[20]

By late 1962, citizens had elected an all-Republican three-member council. J. Hubert Black, Charles E. Miller, and David W. Force who campaigned on a low-density growth ballot, but later approved the Columbia project.[21]![]() The Howard County Planning Commission Chairman Wilmer Sanner declared, "if this adds to the orderly development of the county, that's what we are looking for."[17]: 56 That July, Sanner sold the majority of his 73-acre (30 ha) Simpsonville farm to Howard Research prior to the public announcement.[22] In October 1963, the acquisition was revealed to the residents of Howard County, putting to rest rumors about the mysterious purchases. These had included theories that the site was to become a medical research laboratory or a giant compost heap. Despite the moniker of being a "planned city", the planning for the city occupied Rouse officials for most of 1964 after the announcement while marketing director Scott Ditch was brought from Baltimore's Cross Keys development to promote the project to community groups.[17]: 56 [23]

The Howard County Planning Commission Chairman Wilmer Sanner declared, "if this adds to the orderly development of the county, that's what we are looking for."[17]: 56 That July, Sanner sold the majority of his 73-acre (30 ha) Simpsonville farm to Howard Research prior to the public announcement.[22] In October 1963, the acquisition was revealed to the residents of Howard County, putting to rest rumors about the mysterious purchases. These had included theories that the site was to become a medical research laboratory or a giant compost heap. Despite the moniker of being a "planned city", the planning for the city occupied Rouse officials for most of 1964 after the announcement while marketing director Scott Ditch was brought from Baltimore's Cross Keys development to promote the project to community groups.[17]: 56 [23]

In December 1964 the zoning was rejected by planning director Tom Harris Jr. for handing nearly all planning control to the developer. A media push was instituted to approve the zoning by Dorris Thompson of The Howard County Times, Seymour Barondes of the Howard County Civic Association, and Anita Iribe of the League of Women Voters.[17]: 64 In June 1965 zoning was approved for the project, and Howard Research and Development entered into a $37.5 million construction deed backed by the property.[24][25] Development was temporarily stalled in October 1965 when James and Anna Hepding of Simpsonville sued the planning board, stating New Town zoning was a form of spot zoning benefiting a sole property owner. The case was dropped when developer Homer Gudelsky purchased the estate.[26] Ten years later, former Councilman Charles E. Miller stated that if he could do it over again, he wouldn't have voted to approve Columbia. He felt exploited and felt the subsidized housing would become a problem for the rest of the county.[27] Miller had been defeated in the November 1974 Howard County Council elections, in part as a result of the changed political landscape that Columbia's development brought. In early 1976, a Columbia Flier editorial charged that Miller was a fear-mongering reactionary who had a personal vendetta against Columbia, Rouse and Columbia residents.[28]

Unveiling and growth

[edit]

At the unveiling on June 21, 1967, James Rouse described Columbia as a planned new city which would avoid the leap-frog and spot-zoning development threatening the county.[7] The new city would be complete with jobs, schools, shopping, and medical services, and a range of housing choices. Property taxes from commercial development would cover the additional services with which housing would burden the county. The urban planning process for Columbia included not only planners, but also a convened panel of nationally recognized experts in the social sciences, known as the Work Group. The fourteen member group of men and one woman, Antonia Handler Chayes, met for two days, twice a month, for half a year starting in 1963.[17]: 68 The Work Group suggested innovations for planners in education, recreation, religion, and health care, as well as ways of improving social interactions. Columbia's open classrooms, interfaith centers, and the then-novel idea of a health maintenance organization (HMO) with a group practice of medical doctors (the Columbia Medical Plan) sprung from these meetings. The community's physical plan, with neighborhood and village centers, was also decided. Columbia's "New Town District" zoning ordinance gave developers great flexibility about what to put where, without requiring county approval for each specific project.[citation needed]

In 1968, vice-presidential candidate Spiro Agnew referenced Columbia to reporters, saying, "Government should act as a catalyst to encourage the local governments to encourage industry and business to move next to a planned community," and "I want to lessen the density in the ghettos, and concurrently rebuild the ghetto areas."[29] In 1969, County Executive Omar J. Jones felt that the increase in tax base was lagging behind the need for infrastructure as the operating budget doubled to $15 million in three years.[30] Crime rates shot up around the county by 30–50% a year, with hot spots around the development.[31][32] By 1970, the project required additional financing to continue, borrowing $30 million from Connecticut General, Manufacturers Hanover Trust, and Morgan Guaranty. In 1972, amendments to New Town zoning proposing to place a maximum height for buildings and maintain the original density limit of 2.2 units per acre were opposed by Rouse allies including the Columbia Association, the Ellicott City Businessman's Association and the Columbia Democratic Club.[33] By 1974, the amount owed reached $100,000 million,[dubious – discuss] prompting partner Connecticut General to consider bankruptcy. An effort to create a special taxing district in 1978 and an effort to incorporate with a mayor in 1979 failed.[34] In 1985 Cigna (Connecticut General) divested itself of the project for $120 million. By 1990 Howard Research and Development owed $125,162,689.[35][25] In 2004 the project was sold to General Growth Properties, which went bankrupt in 2008. General Growth Properties submitted a plan for increasing density throughout Columbia in 2004 which was unanimously voted down.[36] Ownership of the project fell to the previous Rouse subsidiary the Howard Hughes Corporation. Howard Hughes submitted a new plan to increase density in 2010 under the Ulman administration that passed unanimously.[citation needed]

Columbia has never incorporated; some governance, however, is provided by the non-profit Columbia Association, which manages common areas and functions as a homeowner association with regard to private property. The first boards were filled entirely with Rouse Company appointees.[30] The first manager of the Columbia Association was John Estabrook Slayton (d. 1967). For Slayton's contributions to the early planning of Columbia, the community center in the Wilde Lake village, Slayton House, was named for him. Wilde Lake was the first village area to be developed in Columbia; accordingly, the town's first high school was Wilde Lake High School, which opened in 1971 as a "model school for the nation". Constructed in the open classroom style, it was razed in 1994 and reconstructed on the same site, reopening in 1996.[citation needed]

Master plan

[edit]To achieve the goals set forth by the Work Group, Columbia's Master Plan called for a series of ten self-contained villages, around which day-to-day life would revolve. The centerpiece of Columbia would be The Mall in Columbia and man-made Lake Kittamaqundi.[37]

Villages and neighborhoods

[edit]

The village concept aimed to provide Columbia a small-town feel (like Easton, Maryland, where James Rouse grew up). Each village comprises several neighborhoods. The village center may contain middle and high schools. All villages have a shopping center, recreational facilities, a community center, a system of bike/walking paths, and homes. Four of the villages have interfaith centers, common worship facilities which are owned and jointly operated by a variety of religious congregations working together.[38]

Most of Columbia's neighborhoods contain single-family homes, townhomes, condominiums and apartments, though some are more exclusive than others. The original plan, following the neighborhood concept of Clarence Perry, would have had all the children of a neighborhood attend the same school, melding neighborhoods into a community and ensuring that all of Columbia's children get the same high-quality education. Rouse marketed the city as being "color blind" as a proponent of Senator Clark's fair housing legislation. If a neighborhood was filled with too many purchasers of a single race, houses would be blocked until the desired ratio was met.[17]: 85

- Village – Neighborhoods (in order of residential opening)

- Wilde Lake – (Est. 1967) Bryant Woods, Faulkner Ridge, Running Brook

- Harper's Choice – (Est. 1968) Longfellow, Swansfield, Hobbit's Glen

- Oakland Mills – (Est. 1969) Thunder Hill, Talbott Springs, Stevens Forest

- Long Reach – (Est. 1971) Phelps Luck, Jeffers Hill, Locust Park, Kendall Ridge

- Owen Brown – (Est. 1972) Dasher Green, Elkhorn, Hopewell

- Town Center – (Est. 1974) Vantage Point, Banneker, Amesbury, Creighton's Run, and Warfield Triangle

- Hickory Ridge – (Est. 1974) Clemens Crossing, Hawthorn, Clary's Forest

- Kings Contrivance – (Est. 1977) Macgill's Common, Huntington, Dickinson

- Dorsey's Search – (Est. 1980) Dorsey Hall, Fairway Hills

- River Hill – (Est. 1990) Pheasant Ridge, Pointers Run

Columbia takes its street names from famous works of art and literature: for example, the neighborhood of Hobbit's Glen takes its street names from the work of J. R. R. Tolkien; Running Brook, from the poetry of Robert Frost; and Clemens Crossing, from the work of Mark Twain. The book Oh, You Must Live in Columbia! chronicles the artistic, poetic, and historical origins of the street and place names in Columbia.[39]

Further expansion

[edit]"The Downtown Columbia Plan" is a 2010 amendment to the county's General Plan of expansion. It is a framework for the revitalization of Downtown Columbia over the next thirty years. Development plans for downtown projects in the years ahead will include details for that project such as neighborhood design guidelines, environmental restoration, public amenities and infrastructure. These development plans must adhere to the framework of the Downtown Columbia Plan as required by the zoning legislation. Over the life of the Downtown Columbia development project, as much as 13 million square feet of retail, commercial, residential, hotel and cultural development is planned.[40]

To be accomplished in three phases, the plan calls for the formation of the non-profit Columbia Downtown Housing Corporation to build an additional 5,500 units of low income housing placed downtown in exchange for increased zoning density for other projects.[41] Additional development includes 4.3 million square feet of commercial office space, 1.25 million square feet of retail space, 640 hotel rooms, Merriweather Post Pavilion redevelopment and a multi-modal transportation system.[42]

Columbia's master developer, the Howard Hughes Corporation, is heading up the expansion project. The project is projected to cost $90 million and will outline development in the community for the next 40 years.[43]

Geography

[edit]

Because Columbia is unincorporated, there is confusion over its exact boundaries. In the strictest definition, Columbia comprises only the land governed under covenants by the Columbia Association. This is a considerably smaller area than the census-designated place (CDP) as defined by the United States Census Bureau. The CDP has a total area of 32.2 square miles (83.4 km2), of which 31.9 square miles (82.7 km2) are land and 0.3 square miles (0.7 km2), or 0.80%, are water.[4] The CDP includes a number of older communities which do not lie within the CA's purview, including the Holiday Hills, Diamondback, and Allview subdivisions and the former town of Simpsonville, as well as some land on the east side of Clarksville. These areas are not part of the "new town", and are not directly served by its amenities. Some of these areas are included in Columbia ZIP codes by the post office, and some are not.

Columbia is located in central Maryland, 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Baltimore, 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Washington, D.C., and 30 miles (48 km) northwest of Annapolis. The community lies in the Piedmont region of Maryland, with its eastern edge at the fall line. The climate tends to hot, humid summers and cool to cold and wet winters. There are occasional large amounts of snowfall that happen every year.

The primary landforms in Columbia are rolling hills and stream valleys; Columbia's road network is laid out to follow the terrain, with many winding streets and cul-de-sacs. Elevations range from about 200 to 500 feet (61 to 152 m) above sea level. Most of Columbia is drained by the Middle Patuxent and Little Patuxent rivers. There are three artificial lakes, created by damming of tributary streams during community construction. In 1965, the Rouse Company leased 7,000 acres (2,800 ha) of farmland staged for development, and earmarked 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) of oak forest for timber harvesting. The company developed a sapling planter to replant sections of cleared land that would use Columbia's W.R. Grace-developed fertilizers.[44] An outer ring of greenspace was abandoned early in the project because the combination with the already required river buffers would have reduced profitable land available for building.[17]: 76 Along with Symphony Woods, many other stands of mature trees have been temporarily maintained in Columbia, including the large Middle Patuxent Environmental Area in the western part of the community between Harper's Choice and River Hill villages, protecting much of the river valley from development.

Climate

[edit]Columbia has a humid subtropical climate, with cool winters and hot, muggy summers.

| Climate data for Columbia, MD | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 42 (6) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

66 (19) |

75 (24) |

84 (29) |

88 (31) |

87 (31) |

79 (26) |

68 (20) |

58 (14) |

46 (8) |

66 (19) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25 (−4) |

27 (−3) |

35 (2) |

44 (7) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

69 (21) |

68 (20) |

60 (16) |

48 (9) |

38 (3) |

29 (−2) |

47 (8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.16 (80) |

3.14 (80) |

4.10 (104) |

3.81 (97) |

4.56 (116) |

4.23 (107) |

4.05 (103) |

3.43 (87) |

4.60 (117) |

3.98 (101) |

4.21 (107) |

3.77 (96) |

47.04 (1,195) |

| Source: weather.com[45] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 8,815 | — | |

| 1980 | 52,518 | 495.8% | |

| 1990 | 75,883 | 44.5% | |

| 2000 | 88,254 | 16.3% | |

| 2010 | 99,615 | 12.9% | |

| 2020 | 104,681 | 5.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[46] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Population by Race in Columbia MD (2020)[47] | ||

| Race | Population | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 104,681 | 100 |

| White | 45,228 | 43 |

| African American | 28,293 | 27 |

| Asian | 13,369 | 13 |

| Hispanic | 10,709 | 10 |

| Two or More Races | 6,015 | 6 |

| Other | 848 | 1 |

| Three or more races | 478 | < 1% |

| American Indian | 524 | ~ 1% |

2010 census

[edit]The 2009-2013 census estimates report the median income for a household in the CDP was $99,877. The per capita income for the CDP was $46,374. About 4.1% of families and 6.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.8% of those under age 18 and 6.4% of those age 65 or over.[48]

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 88,254 people, 34,199 households, and 23,118 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 3,202.0 inhabitants per square mile (1,236.3/km2). There were 35,281 housing units at an average density of 1,280.0 per square mile (494.2/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 66.52% White, 21.47% Black or African American, 0.26% Native American, 7.30% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 1.63% from other races, and 2.76% from two or more races. 4.12% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 14% of Columbia's residents were German, 11% Irish, 10% English, 5% Italian, 4% Polish, 2% Russian, 2% Scottish, 2% Indian, 2% Chinese, 2% Korean, 2% Sub-Saharan African, 2% French, and 2% West Indian.[49]

There were 34,199 households, out of which 35.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.4% were married couples living together, 11.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.4% were non-families. 25.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54 and the average family size was 3.09.

In the CDP, the population was spread out, with 26.3% under the age of 18, 6.7% from 18 to 24, 34.1% from 25 to 44, 25.5% from 45 to 64, and 7.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.7 males.

Economy

[edit]James Rouse conceived of a city, not a suburban bedroom community, and a large area on the eastern edge was allocated for industrial purposes. The centerpiece of this aspect of the development was a General Electric appliance plant on a 1,125-acre (4.55 km2) site previously operated as a cattle farm.[50][51] After an injunction attempt was blocked in 1969, the plant began operations in 1972, peaking at 2,300 of the predicted 12,000 jobs. It was closed in 1990, with all but 21 acres (85,000 m2) of the property being sold back to Howard Research and Development.[17]: 141 One section of the property was subsequently redeveloped for big box retail; the remainder became the large Gateway Commerce office complex, still being expanded.[52] In 1968, Bendix Field Engineering moved to a new 143,000-square-foot (13,300 m2) facility on the historic Woodlawn Plantation where it was used for engineering activity. Howard County purchased the vacant facility creating the Maryland Center for Entrepreneurship in 2011, which relocated to the vacant Patuxent Publishing building in 2014.[53][54] There is still a smaller industrial area to the south of this, but by and large East Columbia is dominated by commercial real estate—office, retail, and wholesale—in contrast to the original plan, which saw the Town Center area as the commercial center of Columbia.[55]

The U.S. federal government is the source of many jobs for Columbians. Several large U.S. Department of Defense installations and R&D facilities surround Columbia, the largest being the National Security Agency at Fort George G. Meade, and the Applied Physics Laboratory south of Columbia, both pre-dating the establishment of Columbia. Companies which have had research facilities in the area include W.R. Grace and Company. Further afield, many Columbians commute to government and government contractor jobs in the Baltimore and Washington, D.C. area.[citation needed][56]

Companies based in Columbia include W.R. Grace and Company,[57][58] Sourcefire, PetMeds, MICROS Systems, Martek Biosciences, Integral Systems, GP Strategies Corporation, Corporate Office Properties Trust, and the consumer research company Nielsen Audio (formerly Arbitron).[citation needed] When MaggieMoo's was an independent company, its headquarters was in Columbia.[58][59]

Shopping

[edit]The Mall in Columbia, located in Town Center, is a large regional shopping mall with three anchor department stores, a multiplex movie theater, and more than 200 stores and restaurants.

There are several other major competing shopping centers in East Columbia, including Dobbin Center strip mall opened in 1983, Snowden Square big box retail on the remainder of the GE industrial site, Columbia Crossing I and II big box retail started in 1997, and Gateway Overlook.[17]: 142

Columbia's nine "village centers" provide residents with nearby shopping as well, often including supermarkets, filling stations, liquor stores, dry cleaners, restaurants, and hair salons. The village centers are laid out so that individual stores are not visible from the road, unlike traditional strip malls. The arrangement is criticized because it makes it difficult for newcomers and non-residents to know what shopping is available; it is praised for eliminating much of the garishness of roadside America.[citation needed]

The village centers have evolved over time. Oakland Mills Village Center in Oakland Mills had a traditional layout—stores located off a central corridor—until its demolition in the late 1990s. The Rouse Company abandoned the village center concept in 2002, selling off the assets to Kimco Realty for $120 million.[60] The Kings Contrivance Village Center in Kings Contrivance underwent major construction in 2007 and 2008 when a new supermarket was added to the center, but maintained the original character of stores around a central corridor and plaza. Owen Brown village center is now managed by GFS Realty, and the Long Reach Village center was declared blighted and purchased by Howard County for resale in 2014.[61]

Arts and culture

[edit]Entertainment and performing arts

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Merriweather Post Pavilion, a well-known outdoor concert venue, attracts many prominent performers.[62] In addition, there are several performing arts organizations that present professional theater, including Toby's Dinner Theatre, Columbia Center for Theatrical Arts and the Young Columbians which have produced the area premieres of several musicals.

Columbia also offers chamber music concerts, children's programs, community outreach programs, master classes, and pre-concert lectures and discussions through the Candlelight Concert Society, a non-profit organization formed by Columbia residents to provide chamber music concerts since 1972.[63]

Howard County Library System

[edit]Howard County Library System (HCLS) is consistently top rated among the nation's public library systems according to Hennen's American Public Library Ratings (HAPLR).[64] Two of the six branches of the Howard County Library System are in Columbia, including the Central Branch in Town Center and the East Columbia Branch in Owen Brown.

Historic sites

[edit]There are four historic National Register of Historic Places sites in Columbia: Christ Church Guilford, Dorsey Hall, Woodlawn, and the Oakland Mills Blacksmith House and Shop. Most historic buildings, mills and plantations within Columbia that qualified for the register, such as Oakland Manor,[65] were not submitted by Rouse company affiliates.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]Rouse, a devout Episcopalian, commissioned a study concerning how places of worship would be integrated into plans for the new town.[13] Dr. Stanley Hallet advised this 1964 work group to economically abandon "The extravagance of church life" in favor of ecumenical establishments that focused resources on retreat centers and non-profit religious corporations.[66] The Rouse Company discouraged individual congregations from purchasing land from the company.[13] In 1966, the Columbia Religious Facilities Corporation was founded to lease interfaith centers to congregations.[67][68] On June 22, 1969, $2.5 million in church donations applied to the CFRC to purchase Columbia land and build an interfaith facility in the village of Wilde Lake. The organization formed the Interfaith Housing Corporation (now the Columbia Housing Corporation) to purchase 300 units of low and moderate income housing in the development with Federal Housing Authority funding.[17]: 97 [69]

Parks and recreation

[edit]Columbia has numerous recreation centers. The homeowners association, the Columbia Association, known to many in Howard County as "CA", builds, operates and maintains most of these facilities. CA operates a variety of recreational facilities, including 23 outdoor swimming pools, five indoor pools, two water slides, ice and roller skating rinks, an equestrian center, a sports park with miniature golf, a skateboard park, batting cages, picnic pavilions, clubhouse and playground, three athletic clubs, numerous indoor and outdoor tennis, basketball, volleyball, squash, pickleball, and racquetball courts, and running tracks.[70]

There are three lakes (Lake Kittamaqundi, Lake Elkhorn, and Wilde Lake) surrounded by parkland for sailing, fishing, and boating; 80 miles (130 km) of paths for jogging, strolling and biking; and 148 tot lots and play areas.

Nine village centers, 15 neighborhood centers, and four senior centers provide space for a large variety of community activities. There are a variety of fairs and celebrations throughout the year, including entertainment on the lakefront of Lake Kittamaqundi during the summer and the Columbia Festival of the Arts.

Columbia also has garden plots for rent, under the guidance of the Columbia Gardeners, which has been in existence since the 1970s. There are about 350 garden plots at three sites in Columbia.[71]

Chiara D'Amore's Community Ecology Institute's Freetown Farm, founded in 2016, uses hands-on gardening to educate people and cultivates communities where people thrive together. Freetown farm was built on the site of Columbia's last working farm. The name Freetown farm refers to the area's historical name and its ties to the Underground Railroad. It features an NAACP garden and donates much of the food that is raise to local food banks.[72]

Education

[edit]

Columbia's public schools are operated by the Howard County Public School System. As of the 2007–2008 school year, the following high schools served some part of Columbia:[73]

- Atholton[74]

- Centennial

- Hammond[75]

- Howard[76]

- Long Reach[77]

- Oakland Mills[78]

- River Hill[79]

- Wilde Lake[80]

Most of these schools also serve students from outside Columbia, as is also the case with some of the middle and elementary schools.

Colleges and universities

[edit]There are no conventional four-year colleges or universities in Columbia, but several college-level programs have facilities there. Howard Community College is located near the town center, while the University of Phoenix, Lincoln College of Technology, Loyola University Maryland, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Maryland University of Integrative Health, and Johns Hopkins University have facilities on the east side of town at Columbia Gateway Business Park. In addition to its original campus in Columbia, HCC also has satellite campuses in Mount Airy, Laurel, and East Columbia, in the Columbia Gateway Business Park.

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Public transit

[edit]Columbia's initial plan called for a minibus system connecting the village centers on a distinct right-of-way that allowed denser development along the route.[81] The routes were not constructed, though minibuses were operated by the Columbia Association under the name "ColumBus". These were eventually taken over by Howard County. Six Howard Transit bus routes served Columbia and connected it with its neighboring areas (such as Ellicott City and the BWI Airport) until they were replaced by Regional Transportation Agency of Central Maryland (RTA) in 2014. Several Maryland Transit Administration (MTA) routes provide access to and from both Washington and Baltimore; MTA weekday commuter bus service connects Columbia to the Washington Metro system. There are no rail stations within Columbia, although the Dorsey MARC Train station is served by RTA buses.

Roads

[edit]

Columbia has a number of roadways that serve the community (see below). All of these highways allow Columbia access to nearby Baltimore, Washington, D.C. and Annapolis.

- U.S. Route 29 Columbia Pike, runs north–south connecting Columbia to Ellicott City and Washington, D.C.

- Interstate 95, runs north–south connecting Columbia to Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

- MD 32 Patuxent Freeway, runs east–west connecting Columbia to Sykesville and Annapolis.

- MD 100 Paul T. Pitcher Memorial Highway, runs east from U.S. Route 29 connecting Columbia to Glen Burnie.

- MD 175 Rouse Parkway, a central artery that runs east–west from the Town Center to Jessup.

- MD 108 Clarksville Pike-Waterloo Road, forms the northern boundary of the community by running east–west from Clarksville to Ellicott City.

Healthcare

[edit]Medical care is available at Howard County General Hospital, affiliated with Baltimore's Johns Hopkins Hospital. The Columbia Medical Plan was founded in 1967 as a health maintenance organization (HMO) available to citizens of Columbia.[17]: 99 [82] In more recent years, however, this plan has divided into separate medical groups that simply share the Twin Knolls buildings. Today, there is a Kaiser Permanente facility located in the Columbia Gateway industrial park. There are also a number of clinics, such as the Righttime Medical Care center and Patient First.

Notable people

[edit]- Stephen Amidon, author, whose 2000 novel, The New City, is set in a fictionalized Columbia in the 1970s

- Bob Beaumont (1932–2011), founder of Citicar, an electric automobile manufacturer from 1974 to 1977[83]

- Jayson Blair, disgraced former New York Times reporter

- Zach Brown, linebacker for the NFL's Washington Redskins

- Michael Chabon, Pulitzer Prize–winning author

- Dan Charnas, journalist and author of "The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop"[84]

- Frank Cho, creator of Liberty Meadows comic strip

- George Colligan, New York–based jazz pianist

- Cristeta Comerford, White House executive chef

- Jack Douglass, internet personality on YouTube[85]

- Mary Downing Hahn, award-winning author of young adult literature

- Brent Faiyaz, singer and record producer

- Kevin Frazier, journalist and TV broadcaster

- Gallant, Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter

- Alicia Graf Mack, dancer, director of dance division at Juilliard School

- Justin Gorham (born 1998), basketball player in the Israeli Basketball Premier League

- Tom Green, ultra-runner[86]

- Greg Hawkes, keyboardist for new wave band The Cars

- David Hobby, professional photographer and author of the Strobist.com lighting blog

- Stephen Hunter, Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic and author

- Julia Ioffe (born 1982), Russian-born American journalist

- Kerry G. Johnson, award-winning caricaturist, cartoonist and children's book illustrator

- Robert Kolker, author and editor

- Mark Levine, New York City Council member

- Laura Lippman, award-winning mystery author

- Steve Lombardozzi, former professional baseball player

- Steve Lombardozzi Jr., professional baseball player

- Suzanne Malveaux, CNN reporter

- Aaron Maybin, defensive end for NFL's New York Jets

- Aaron McGruder, animator and cartoonist (The Boondocks)

- Edward Norton, Academy Award–nominated actor and grandson of James Rouse, made his professional debut at age 8 at Toby's Dinner Theatre in the Town Center

- Alexis Ohanian, co-founder of Reddit

- Toby Orenstein, theater director and founder of Toby's Dinner Theatre, Columbia Center for Theatrical Arts, and the Young Columbians

- Randy Pausch, professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University, author of The Last Lecture

- Ian Jones-Quartey, writer, storyboard artist, animator and voice actor (OK K.O.! Let's Be Heroes)

- Elise Ray, Olympic gymnast

- James W. Rouse, urban planner, real estate developer and philanthropist; grandfather of actor Edward Norton

- Peter Salett, singer-songwriter

- Greg Saunier, drummer for Deerhoof

- Christian Siriano, fashion designer, winner of fourth season of Project Runway (born in Columbia)

- Dave Sitek, guitarist and music producer, member of the band TV on the Radio

- Linda Tripp, central figure in the Monica Lewinsky scandal

- Terry Virts, astronaut

- Void, punk band

- Greg Whittington, basketball player

- David Byrne, musician

- Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle, OM, KBE, inventor of the jet engine

- Oprah Winfrey, talk show host, television producer, actress, author, and philanthropist; Winfrey lived in Columbia during the time she worked at WJZ-TV in Baltimore between 1976 and 1983[87][88][89]

In popular culture

[edit]Columbia is mentioned in the novel, Butchers Hill, by Laura Lippman.[90] The novel is largely set in Baltimore City and describes Columbia as a utopian experiment with huge homes and affluent residents.[91] The residents are portrayed as racially homogeneous and largely white.[92] The novel was written in 1998[93] and Lippman herself lived in Columbia in the 1970s.[94]

Sister cities

[edit]Columbia is a sister city to Cergy-Pontoise, France, Tres Cantos, Spain, Tema, Ghana, Cap-Haïtien, Haiti, and Liyang, China. The Columbia Association International and Multicultural Programs Advisory Committee organizes a summer exchange program for French and Spanish students enrolled in Howard County Public Schools.[95] In 2013, CA announced its new sister city relationship with Tema, a port city in Ghana. The occasion was marked with a Ghana Fest on November 17, 2013,[96] and the official agreement was signed in 2014.[97] In 2016, Cap-Haïtien, Haiti became a sister city followed by Liyang, China in 2018.[98][99][100] The sister city agreement with Liyang included a requirement that Columbia support the China government's One China principle.[101]

- Cergy-Pontoise, France (1977)[102]

- Tres Cantos, Spain (1990)[102]

- Tema, Ghana (2014)[97]

- Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (2016)[97]

- Liyang, China (2018)[100]

Related cities

[edit]The Rouse Company, now owned by the Howard Hughes Corporation, owns and operates multiple HUD Title VII-New Town planned community developments along with Columbia. These include The Woodlands, Texas, Bridgeland Community, Texas, and Summerlin, Nevada.[103]

References

[edit]- ^ Levinson, David M. (2003). "The Next America Revisited". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 22 (329): 329–344. doi:10.1177/0739456X03022004001. hdl:11299/179914. S2CID 13196176.

- ^ "Columbia Archives". Columbia Association. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts - Columbia CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. n.d. Archived from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ "Age and Sex: 2015 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (S0101): All places within Maryland". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ Galambos, Louis (2011). The Creative Society-and the Price Americans Paid for It. Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-1107600997.

- ^ a b 1909digital (February 29, 2024). "City of Columbia". Maryland 400. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Howard County's History". Howard County, Maryland. Archived from the original on August 22, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ "Howard County Land Preservation, Parks and Recreation Plan Update" (PDF). Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 22, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ Unless otherwise noted, this section is derived from Joseph R. Mitchell; David Stebenne (March 31, 2007). New City Upon a Hill: A History of Columbia, Maryland. Arcadia. pp. 28–56. ISBN 9781614230991.

- ^ "C.R.D. Board Backs Swap of Stock With Rouse Firm," The Baltimore Sun, February 9, 1966, p. C11

- ^ "Suit Filed to Void Rouse's Recent Acquisition of Firm," The Baltimore Sun, August 21, 1966, p. FE29

- ^ a b c Numrich, Paul D. (2019). "How important is religion in interreligious relationships? Interreligious space-sharing as a case study". Journal of Interreligious Studies. 26: 42–57. Archived from the original on November 11, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ Haar, Charles Monroe; Liebman, Lance. Property and Law. Little, Brown. p. 685.

- ^ Forsythe. Reforming Suburbia: The Planned Communities of Irvine, Columbia, and The Woodlands. p. 114.

- ^ a b Adam Sachs (November 16, 1993). "Developer envisions 22 homes on 10 acres of Dasher Homestead; Moxley has ties to Columbia's birth". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Joseph R. Mitchell; David Stebenne. New City Upon a Hill: A History of Columbia, Maryland.

- ^ Barbara Kellner. Columbia. p. 10.

- ^ Gurney Breckenfeld. Columbia and the New Cities. p. 233.

- ^ "H. Max Ammerman Dies; Development Suburban Malls". The Washington Post. November 1, 1988.

- ^ Stebenne, David; Mitchell, Joseph Rocco (2007). New City Upon a Hill: A History of Columbia, Maryland. Arcadia Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 9781614230991.

- ^ Maryland State Archives Book 440. pp. 80–82.

- ^ Jacques Kelly (June 20, 2009). "Rouse Official Oversaw Naming Of Columbia's Streets, Helped Gain Harborplace Approval". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Columbia Archives (June 14, 1992). "Columbia's first 25 years: a chronology". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "HOWARD COUNTY, MARYLAND et al. v. HOWARD RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION et al" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ "Flashbacks". The Baltimore Sun. October 17, 1990.

- ^ Michael J. Clark (June 19, 1977). "At youthful age of 10, Columbia is feeling like a grown-up new town". The Baltimore Sun. p. B1.

- ^ "Middle Patuxent: a solid proposal". The Columbia Flier. January 15, 1976.

- ^ Richard Reeves (August 25, 1968). "Agnew Says Vice President Should Quit in a Major Rift". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Ellen Hoffman (September 26, 1969). "New Towners, The Voiceless Marylanders: Columbia Citizens Seeking More Say". The Washington Post.

- ^ Tom Huth (September 19, 1972). "Howard County Boom Malignant or Benign?". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Rural Howard County Goes on a Crime Alert". The Washington Post. December 11, 1971.

- ^ Michael J. Clark (June 22, 1972). "Rouse campaigning against Columbia zoning amendments". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Micheal J. Clark (February 21, 1979). "Plan to Incorporate Columbia Faces Defeat". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Joshua Olsen. A Biography of James Rouse. p. 234.

- ^ "Howard Week". The Baltimore Sun. September 19, 2004.

- ^ "Columbia Jewish & Kosher Guide 2024: Kosher Info in Columbia, Maryland". www.totallyjewishtravel.com. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ Hurley, Amanda (July 13, 2017). "Here's a suburban experiment cities can learn from". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ^ "Publications: Books". Columbia Archives. Columbia Association. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011.

- ^ "DOWNTOWN COLUMBIA PLAN: A General Plan Amendment" (PDF). Howard County, Maryland. February 1, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ Lindsey McPherson (September 24, 2012). "Group hopes to provide affordable housing in downtown Columbia". Patuxent.

- ^ "FAQ Downtown Columbia, MD." Howard County, Maryland. 2012. <http://www.columbiamd.com/plan/faq/ Archived October 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine> Retrieved October 2, 2012

- ^ Waseem, Fatimah (November 9, 2016). "Howard County Times". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "HRD Howards Biggest Farmer". The Howard County Times. March 31, 1965.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Columbia, MD (21044)". Weather.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "Census 2020 P.L. 94-171 Data". Maryland.gov. Archived from the original on August 9, 2024. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics". Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Columbia, MD, Ancestry & Family History". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Laura Barnhardt (May 19, 1996). "Farmers: Town's forgotten pioneers. In 1960s, they sold land to Rouse, making Columbia possible". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ "Columbia GE Plant Grows". The Washington Post. May 17, 1973.

- ^ "STATEMENT OF BASIS GENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANY COLUMBIA, MARYLAND EPA ID NO. MDD046279311 JUNE 2012" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ Peter Muncie (September 20, 1968). "Bendix Field Unit to Move". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Amanda Yeager (May 8, 2014). "Howard Co. to buy Columbia Flier building as headquarters for business incubator". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Nicholas Dagen Bloom (2005). "Merchant of Illusion: James Rouse, America's Salesman of the Businessman's Utopia". The Professional Geographer. 57 (1): 114. Bibcode:2005ProfG..57..148Z. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.2005.466_6.x.

- ^ West, Tom (April 2014). "Fisking Pittsboro Matters: Let's take a look at Columbia vs Chatham Park". Archived from the original on June 28, 2024. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- ^ "Grace in Maryland Archived 2011-07-03 at the Wayback Machine." W.R. Grace and Company. Retrieved on June 29, 2011. "Corporate Headquarters & Grace Davison Headquarters W.R. Grace & Co. 7500 Grace Drive Columbia, MD 2104"

- ^ a b "Columbia CDP, Maryland Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on February 26, 2010.

- ^ Bishop, Tricia (February 16, 2007). "Firm with Md. roots buys MaggieMoo's". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore. Archived from the original on November 11, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

...Richard J. Sharoff bought the company. He moved the operation to Columbia...

- ^ Vozzella, Laura (February 8, 2002). "Rouse selling Columbia centers". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on December 7, 2023. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ Lavoie, Luke (May 30, 2014). "Columbia market study presents recommendations". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ Mitchell, Joseph Rocco; Stebenne, David L. (2007). New City Upon a Hill: A History of Columbia, Maryland. History Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-5962-9067-9.

- ^ "Candlelight Concert Society". Candlelight Concert Society. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2013.[better source needed]

- ^ Hennen's American Public Library Ratings. Hennen's American Public Library Ratings Archived September 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Hennen's American Public Library Ratings (HAPLR), 2010, retrieved October 18, 2010

- ^ "National Register Historic Listings Howard County". Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ "Columbia: Ecumenical Adventure". The Communicator: News of the Episcopal Church in Maryland. November 1966.

- ^ Martin M. Chemers. Culture and Environment. p. 285.

- ^ "Columbia Religious Facilities Corporation". Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ Nicholas Dagen Bloom. Suburban Alchemy: 1960s New Towns and the Transformation of the American Dream. p. 172.

- ^ "Facilities". Columbia Association. February 2, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Doug Miller, "Turning over a new leaf could be growing concern", Columbia Flyer, May 31, 2007, page 17

- ^ "Freetown Farm is cultivating veggies — and nurturing communities". Today. Columbia Maryland. October 7, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ "Howard County High School Attendance Area Map" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2009.

- ^ "Atholton High School". ahs.hcpss.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "Hammond High School". Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2005.

- ^ "Howard High School". Archived from the original on August 26, 2005. Retrieved July 10, 2005.

- ^ "LRHS Home". Archived from the original on April 15, 2005. Retrieved July 10, 2005.

- ^ "Oakland Mills High School". Archived from the original on September 12, 2005. Retrieved July 10, 2005.

- ^ "River Hill High School". Archived from the original on May 29, 2005. Retrieved July 10, 2005.

- ^ "Home". www.wildelake.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2005. Retrieved July 10, 2005.

- ^ Edward P. Eichler; Marshall Kaplan. The Community Builders. p. 69.

- ^ Harold S. Luft. Health Maintenance Organizations: Dimensions of Performance. p. 345.

- ^ Bunkley, Nick. "Bob Beaumont, Who Popularized Electric Cars, Dies at 79" Archived June 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, October 29, 2011. Accessed October 30, 2011.

- ^ "Paid In Full: An Interview With Dan Charnas, Author of "The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop" (Part 1)". Scottscope. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Brookes May (October 25, 2009). "Student strikes YouTube gold". The Eagle. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ Nitkin, Karen (November 21, 2007). "Tom Green Ultrarunner - A laid-back Columbia man is a pioneer in running races of 50 miles or longer". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ "Oprah Winfrey - Columbia TV personality's 'flying high'", Columbia Flier, September 14, 1978, p. 38

- ^ "Oprah Had a Presence in Maryland". Columbia, MD Patch. May 31, 2011. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ "OPRAH DIDN'T FEEL LIKE WINNER UNTIL SHE WAS A LOSER". Deseret News. January 1, 1997. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Lippman, Laura (1998). Butchers Hill. Harper. ISBN 978-0062400628.

- ^ Lippman, Laura (1998). Butchers Hill. Harper. ISBN 978-0062400628.

- ^ Lippman, Laura (1998). Butchers Hill. Harper. ISBN 978-0062400628.

- ^ www.bibliopolis.com. "BUTCHERS HILL by Laura Lippman on Type Punch Matrix". Type Punch Matrix. Retrieved September 7, 2024.

- ^ "Laura's Bio | Laura Lippman". Retrieved September 7, 2024.

- ^ Lemke, Tim (October 25, 2018). "Student summer exchange program sends teens to France and Spain, welcomes Europeans to Columbia". Columbia Association. Archived from the original on September 25, 2023. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ "International & Multicultural Advisory Committee (IMAC) Meeting Agenda" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 14, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Sister Cities". Columbia Association. Archived from the original on June 9, 2024. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ "Columbia, Maryland's newest sister city is Liyang, China". Columbia Association. September 11, 2018. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Holzberg, Janene (June 15, 2018). "Columbia poised to add China's Liyang as sister city". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Magnier, Mark (August 9, 2024). "US-China sister-city project, meant to build bridges, targeted as the two countries spar". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on August 9, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "Columbia Association". Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ "Howard Hughes Corporation Properties". Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Joseph Rocco Mitchell and David L. Stebenne, New City Upon A Hill: A History of Columbia, Maryland (The History Press, 2007)

- Missy Burke, Robin Emrich and Barbara Kellner, Oh, you must live in Columbia: The origins of place names in Columbia, Maryland (2008)

- Barbara Kellner, Columbia – Images of America

External links

[edit]- Columbia Association, Inc.

- Columbia Archives

- Columbia Maryland

- Stephen Amidon talks to Kojo Nnamdi about growing up in Columbia in the 1970s (interview)

- "A haven for interracial love amid relentless racism: Columbia turns 50" by DeNeen L. Brown, The Washington Post July 21, 2017