Colistin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Xylistin, Coly-Mycin M, Colobreathe, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682860 |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | Topical, by mouth, intravenous, intramuscular, inhalation |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 0% |

| Elimination half-life | 5 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.012.644 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

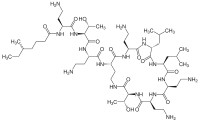

| Formula | C52H98N16O13 |

| Molar mass | 1155.455 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Colistin, also known as polymyxin E, is an antibiotic medication used as a last-resort treatment for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections including pneumonia.[7][8] These may involve bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Acinetobacter.[9] It comes in two forms: colistimethate sodium can be injected into a vein, injected into a muscle, or inhaled, and colistin sulfate is mainly applied to the skin or taken by mouth.[10] Colistimethate sodium[11] is a prodrug; it is produced by the reaction of colistin with formaldehyde and sodium bisulfite, which leads to the addition of a sulfomethyl group to the primary amines of colistin. Colistimethate sodium is less toxic than colistin when administered parenterally. In aqueous solutions, it undergoes hydrolysis to form a complex mixture of partially sulfomethylated derivatives, as well as colistin. Resistance to colistin began to appear as of 2015.[12]

Common side effects of the injectable form include kidney problems and neurological problems.[8] Other serious side effects may include anaphylaxis, muscle weakness, and Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea.[8] The inhaled form may result in constriction of the bronchioles.[8] It is unclear if use during pregnancy is safe for the fetus.[13] Colistin is in the polymyxin class of medications.[8] It works by breaking down the cytoplasmic membrane, which generally results in bacterial cell death.[8]

Colistin was discovered in 1947 and colistimethate sodium was approved for medical use in the United States in 1970.[9][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[14] The World Health Organization classifies colistin as critically important for human medicine.[15] It is available as a generic medication.[16] It is derived from bacteria of the genus Paenibacillus.[10]

Medical uses

[edit]Antibacterial spectrum

[edit]Colistin has been effective in treating infections caused by Pseudomonas, Escherichia, and Klebsiella species. The following represents minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) susceptibility data for a few medically significant microorganisms:[17][18]

- Escherichia coli: 0.12–128 μg/mL

- Klebsiella pneumoniae: 0.25–128 μg/mL

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa: ≤0.06–16 μg/mL

For example, colistin in combination with other drugs is used to attack P. aeruginosa biofilm infection in lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis.[19] Biofilms have a low-oxygen environment below the surface where bacteria are metabolically inactive, and colistin is highly effective in this environment. However, P. aeruginosa reside in the top layers of the biofilm, where they remain metabolically active.[20] This is because surviving tolerant cells migrate to the top of the biofilm via pili and form new aggregates via quorum sensing.[21]

Administration and dosage

[edit]Forms

[edit]Two forms of colistin are available commercially: colistin sulfate and colistimethate sodium (colistin methanesulfonate sodium, colistin sulfomethate sodium). Colistin sulfate is cationic; colistimethate sodium is anionic. Colistin sulfate is stable, whereas colistimethate sodium is readily hydrolysed to a variety of methanesulfonated derivatives. Colistin sulfate and colistimethate sodium are eliminated from the body by different routes. With respect to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, colistimethate is the inactive prodrug of colistin. The two drugs are not interchangeable.

- Colistimethate sodium may be used to treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in patients with cystic fibrosis, and it has come into recent use for treating multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection, although resistant forms have been reported.[22][23] Colistimethate sodium has also been given intrathecally and intraventricularly in Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa meningitis and ventriculitis[24][25][26][27] Some studies have indicated that colistin may be useful for treating infections caused by carbapenem-resistant isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii.[23]

- Colistin sulfate may be used to treat intestinal infections, or to suppress colonic flora. Colistin sulfate is also used in topical creams, powders, and otic solutions.

- Colistin A (polymyxin E1) and colistin B (polymyxin E2) can be purified individually to research and study their effects and potencies as separate compounds.

Dosage

[edit]Colistin sulfate and colistimethate sodium may both be given intravenously, but the dosing is complicated. The different labeling of the parenteral products of colistin methanesulfonate in different parts of the world was noted by Li et al.[28] Colistimethate sodium manufactured by Xellia (Colomycin injection) is prescribed in international units, whereas colistimethate sodium manufactured by Parkdale Pharmaceuticals (Coly-Mycin M Parenteral) is prescribed in milligrams of colistin base:

- Colomycin 1,000,000 units is 80 mg colistimethate;[29]

- Coly-mycin M 150 mg colistin base is 360 mg colistimethate or 4,500,000 units.[30]

Because colistin was introduced into clinical practice over 50 years ago, it was never subject to the regulations that modern drugs are subject to, and therefore there is no standardised dosing of colistin and no detailed trials on pharmacology or pharmacokinetics. The optimal dosing of colistin for most infections is therefore unknown. Colomycin has a recommended intravenous dose of 1 to 2 million units three times daily for patients weighing 60 kg or more with normal renal function. Coly-Mycin has a recommended dose of 2.5 to 5 mg/kg colistin base a day, which is equivalent to 6 to 12 mg/kg colistimethate sodium per day. For a 60 kg man, therefore, the recommended dose for Colomycin is 240 to 480 mg of colistimethate sodium, yet the recommended dose for Coly-Mycin is 360 to 720 mg of colistimethate sodium. Likewise, the recommended "maximum" dose for each preparation is different (480 mg for Colomycin and 720 mg for Coly-Mycin). Each country has different generic preparations of colistin, and the recommended dose depends on the manufacturer. This complete absence of any regulation or standardisation of dose makes intravenous colistin dosing difficult for the physician. [citation needed]

Colistin has been used in combination with rifampicin; evidence of in vitro synergy exists,[31][32] and the combination has been used successfully in patients.[33] There is also in vitro evidence of synergy for colistimethate sodium used in combination with other antipseudomonal antibiotics.[34]

Colistimethate sodium aerosol (Promixin; Colomycin Injection) is used to treat pulmonary infections, especially in cystic fibrosis. In the UK, the recommended adult dose is 1–2 million units (80–160 mg) nebulised colistimethate twice daily.[35][29] Nebulized colistin has also been used to decrease severe exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[36]

Resistance

[edit]Resistance to colistin is rare, but has been described. As of 2017[update], no agreement exists about how to define colistin resistance. The Société Française de Microbiologie uses a MIC cut-off of 2 mg/L, whereas the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy sets a MIC cutoff of 4 mg/L or less as sensitive, and 8 mg/L or more as resistant. No standards for describing colistin sensitivity are given in the United States.

The first known colistin-resistance gene in a plasmid which can be transferred between bacterial strains is mcr-1. It was found in 2011 in China on a pig farm where colistin is routinely used and became publicly known in November 2015.[37][38] The presence of this plasmid-borne gene was confirmed starting December 2015 in South-East Asia, several European countries,[39] and the United States.[40] It is found in certain strains of the bacteria Paenibacillus polymyxa.[citation needed]

India reported the first detailed colistin-resistance study, which mapped 13 colistin-resistant infections recorded over 18 months. It concluded that pan-drug-resistant infections, particularly those in the bloodstream, have a higher mortality. Multiple other cases were reported from other Indian hospitals.[41][42] Although resistance to polymyxins is generally less than 10%, it is more frequent in the Mediterranean and South-East Asia (Korea and Singapore), where colistin resistance rates are increasing.[43] Colistin-resistant E. coli was identified in the United States in May 2016.[44]

A recent review from 2016 to 2021 fount that E. coli is the dominant species harbouring mcr genes. Plasmid - mediated colistin resistance is also conferred upon other species that carry different genes resistant to antibiotics. The emergence of the mcr-9 gene is quite remarkable.[45]

Use of colistin to treat Acinetobacter baumannii infections has led to the development of resistant bacterial strains. They have also developed resistance to the antimicrobial compounds LL-37 and lysozyme, produced by the human immune system. This cross-resistance is caused by gain-of-function mutations to the pmrB gene, which controls the expression of lipid A phosphoethanolamine transferases (similar to mcr-1) located on the bacterial chromosome.[46] Similar results have been obtained with mcr-1 positive E. coli, which became better at surviving a mixture of animal antimicrobial peptides in vitro and more effective at killing infected caterpillars.[47]

Not all resistance to colistin and some other antibiotics is due to the presence of resistance genes.[48] Heteroresistance, the phenomenon wherein apparently genetically identical microbes exhibit a range of resistance to an antibiotic,[49] has been observed in some species of Enterobacter since at least 2016[48] and was observed in some strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae in 2017–2018.[50] In some cases this phenomenon has significant clinical consequences.[50]

Inherently resistant

[edit]- Brucella

- Burkholderia cepacia

- Chryseobacterium indologenes

- Edwardsiella

- Elizabethkingia meningoseptica

- Francisella tularensis spp.

- Gram-negative cocci

- Helicobacter pylori

- Moraxella catarrhalis

- Morganella spp.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis

- Proteus

- Providencia

- Serratia

- Some strains of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia[51]

Variable resistance

[edit]Adverse reactions

[edit]The main toxicities described with intravenous treatment are nephrotoxicity (damage to the kidneys) and neurotoxicity (damage to the nerves),[52][53][54][55] but this may reflect the very high doses given, which are much higher than the doses currently recommended by any manufacturer and for which no adjustment was made for pre-existing renal disease. Neuro- and nephrotoxic effects appear to be transient and subside on discontinuation of therapy or reduction in dose.[56]

At a dose of 160 mg colistimethate IV every eight hours, very little nephrotoxicity is seen.[57][58] Indeed, colistin appears to have less toxicity than the aminoglycosides that subsequently replaced it, and it has been used for extended periods up to six months with no ill effects.[59] Colistin-induced nephrotoxicity is particularly likely in patients with hypoalbuminemia.[60]

The main toxicity described with aerosolised treatment is bronchospasm,[61] which can be treated or prevented with the use of β2-adrenergic receptor agonists such as salbutamol[62] or following a desensitisation protocol.[63]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Colistin is a polycationic peptide and has both hydrophilic and lipophilic moieties.[64] These cationic regions interact with the bacterial outer membrane by displacing magnesium and calcium bacterial counter ions in the lipopolysaccharide.[citation needed] The hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions interact with the cytoplasmic membrane just like a detergent, solubilizing the membrane in an aqueous environment.[citation needed] This effect is bactericidal even in an isosmolar environment.[citation needed]

Colistin binds to lipopolysaccharides and phospholipids in the outer cell membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. It competitively displaces divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) from the phosphate groups of membrane lipids, which leads to disruption of the outer cell membrane, leakage of intracellular contents and bacterial death.

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]No clinically useful absorption of colistin occurs in the gastrointestinal tract. For systemic infection, colistin must therefore be given by injection. Colistimethate is eliminated by the kidneys, but colistin is eliminated by non-renal mechanism(s) that are as of yet not characterised.[65][66]

History

[edit]Colistin was first isolated in Japan in 1949 by Y. Koyama, from a flask of fermenting Bacillus polymyxa var. colistinus,[67] and became available for clinical use in 1959.[68]

Colistimethate sodium, a less toxic prodrug, became available for injection in 1959. In the 1980s, polymyxin use was widely discontinued because of nephro- and neurotoxicity. As multi-drug resistant bacteria became more prevalent in the 1990s, colistin started to get a second look as an emergency solution, in spite of toxicity.[69]

Colistin has also been used in agriculture, particularly in China from the 1980s onwards. Chinese production for agriculture exceeded 2700 tons in 2015. China banned colistin use for livestock growth promotion in 2016.[70]

Biosynthesis

[edit]The biosynthesis of colistin requires the use of three amino acids: threonine, leucine, and 2,4-diaminobutryic acid. The linear form of colistin is synthesized before cyclization. Non-ribosomal peptide biosynthesis begins with a loading module and then the addition of each subsequent amino acid. The subsequent amino acids are added with the help of an adenylation domain (A), a peptidyl carrier protein domain (PCP), an epimerization domain (E), and a condensation domain (C). Cyclization is accomplished by a thioesterase.[71] The first step is to have a loading domain, 6-methylheptanoic acid, associate with the A and PCP domains. Now with a C, A, and PCP domain that is associated with 2,4-diaminobutryic acid. This continues with each amino acid until the linear peptide chain is completed. The last module will have a thioesterase to complete the cyclization and form the product colistin.

References

[edit]- ^ "Drug Product Database". Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Colobreathe 1,662,500 IU inhalation powder, Hard Capsules – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Colomycin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for solution for injection, infusion or inhalation – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 27 May 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Promixin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for Nebuliser Solution – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 23 September 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Coly-Mycin M- colistimethate injection". DailyMed. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Colobreathe EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Pogue JM, Ortwine JK, Kaye KS (April 2017). "Clinical considerations for optimal use of the polymyxins: A focus on agent selection and dosing". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 23 (4): 229–233. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.023. PMID 28238870.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Colistimethate Sodium Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ a b Falagas ME, Grammatikos AP, Michalopoulos A (October 2008). "Potential of old-generation antibiotics to address current need for new antibiotics". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 6 (5): 593–600. doi:10.1586/14787210.6.5.593. PMID 18847400. S2CID 13158593.

- ^ a b Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, Mandell GL (2009). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 469. ISBN 9781437720600.

- ^ Bergen PJ, Li J, Rayner CR, Nation RL (June 2006). "Colistin methanesulfonate is an inactive prodrug of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 50 (6): 1953–1958. doi:10.1128/AAC.00035-06. PMC 1479097. PMID 16723551.

- ^ Hasman H, Hammerum AM, Hansen F, Hendriksen RS, Olesen B, Agersø Y, et al. (2015-12-10). "Detection of mcr-1 encoding plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from human bloodstream infection and imported chicken meat, Denmark 2015". Euro Surveillance. 20 (49): 30085. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.49.30085. PMID 26676364.

- ^ "Colistimethate (Coly Mycin M) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine (6th revision ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/312266. ISBN 9789241515528.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 547. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "Polymyxin E (Colistin) – The Antimicrobial Index Knowledgebase – TOKU-E". Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Colistin sulfate, USP Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Data" (PDF). 3 March 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ Herrmann G, Yang L, Wu H, Song Z, Wang H, Høiby N, et al. (November 2010). "Colistin-tobramycin combinations are superior to monotherapy concerning the killing of biofilm Pseudomonas aeruginosa". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 202 (10): 1585–1592. doi:10.1086/656788. PMID 20942647.

- ^ Pamp SJ, Gjermansen M, Johansen HK, Tolker-Nielsen T (April 2008). "Tolerance to the antimicrobial peptide colistin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms is linked to metabolically active cells, and depends on the pmr and mexAB-oprM genes". Molecular Microbiology. 68 (1): 223–240. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06152.x. PMID 18312276. S2CID 44556845.

- ^ Chua SL, Yam JK, Hao P, Adav SS, Salido MM, Liu Y, et al. (February 2016). "Selective labelling and eradication of antibiotic-tolerant bacterial populations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms". Nature Communications. 7: 10750. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710750C. doi:10.1038/ncomms10750. PMC 4762895. PMID 26892159.

- ^ Reis AO, Luz DA, Tognim MC, Sader HS, Gales AC (August 2003). "Polymyxin-resistant Acinetobacter spp. isolates: what is next?". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (8): 1025–1027. doi:10.3201/eid0908.030052. PMC 3020604. PMID 12971377.

- ^ a b Towner KJ (2008). "Molecular Basis of Antibiotic Resistance in Acinetobacter spp.". Acinetobacter Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-306-43902-5. Archived from the original on 2012-02-07.

- ^ Benifla M, Zucker G, Cohen A, Alkan M (July 2004). "Successful treatment of Acinetobacter meningitis with intrathecal polymyxin E". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 54 (1): 290–292. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh289. PMID 15190037.

- ^ Yagmur R, Esen F (2006). "Intrathecal colistin for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventriculitis: report of a case with successful outcome". Critical Care. 10 (6): 428. doi:10.1186/cc5088. PMC 1794456. PMID 17214907.

- ^ Motaouakkil S, Charra B, Hachimi A, Nejmi H, Benslama A, Elmdaghri N, et al. (October 2006). "Colistin and rifampicin in the treatment of nosocomial infections from multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii". The Journal of Infection. 53 (4): 274–278. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2005.11.019. PMID 16442632.

- ^ Karakitsos D, Paramythiotou E, Samonis G, Karabinis A (November 2006). "Is intraventricular colistin an effective and safe treatment for post-surgical ventriculitis in the intensive care unit?". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 50 (10): 1309–1310. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01126.x. PMID 17067336. S2CID 25679033.

- ^ Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL (September 2006). "Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 6 (9): 589–601. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(06)70580-1. PMID 16931410.

- ^ a b "Colomycin Injection". Summary of Product Characteristics. electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC). 18 May 2016. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ "COMMITTEE FOR VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCTS: COLISTIN: SUMMARY REPORT (2)" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. January 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2006. NB. Colistin base has an assigned potency of 30 000 IU/mg

- ^ Ahmed N, Wahlgren NG (2003). "Effects of blood pressure lowering in the acute phase of total anterior circulation infarcts and other stroke subtypes". Cerebrovascular Diseases. 15 (4): 235–243. doi:10.1159/000069498. PMID 12686786. S2CID 12205902.

- ^ Hogg GM, Barr JG, Webb CH (April 1998). "In-vitro activity of the combination of colistin and rifampicin against multidrug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 41 (4): 494–495. doi:10.1093/jac/41.4.494. PMID 9598783.

- ^ Petrosillo N, Chinello P, Proietti MF, Cecchini L, Masala M, Franchi C, et al. (August 2005). "Combined colistin and rifampicin therapy for carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections: clinical outcome and adverse events". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 11 (8): 682–683. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01198.x. PMID 16008625.

- ^ Rynn C, Wootton M, Bowker KE, Alan Holt H, Reeves DS (January 1999). "In vitro assessment of colistin's antipseudomonal antimicrobial interactions with other antibiotics". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 5 (1): 32–36. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00095.x. PMID 11856210.

- ^ "Promixin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for Nebuliser Solution". Patient Information Leafle. electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC). 12 January 2016. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017.

- ^ Bruguera-Avila N, Marin A, Garcia-Olive I, Radua J, Prat C, Gil M, Ruiz-Manzano J (2017). "Effectiveness of treatment with nebulized colistin in patients with COPD". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 12: 2909–2915. doi:10.2147/COPD.S138428. PMC 5634377. PMID 29042767.

- ^ Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. (February 2016). "Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 16 (2): 161–168. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. PMID 26603172.

- ^ Zhang S. "Resistance to the Antibiotic of Last Resort Is Silently Spreading". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

- ^ McKenna M (2015-12-03). "Apocalypse Pig Redux: Last-Resort Resistance in Europe". Phenomena. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "First discovery in United States of colistin resistance in a human E. coli infection". www.sciencedaily.com. Archived from the original on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ^ "Emergence of Pan drug resistance amongst gram negative bacteria! The First case series from India". December 2014.

- ^ "New worry: Resistance to 'last antibiotic' surfaces in India". The Times of India. 28 December 2014. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014.

- ^ Bialvaei AZ, Samadi Kafil H (April 2015). "Colistin, mechanisms and prevalence of resistance". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 31 (4): 707–721. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1018989. PMID 25697677. S2CID 33476061.

- ^ "Discovery of first mcr-1 gene in E. coli bacteria found in a human in United States". cdc.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 31 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-07-11. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ Chatzidimitriou M, Kavvada A, Kavvadas D, Kyriazidi MA, Meletis G, Chatzopoulou F, Chatzidimitriou D (December 2021). "mcr Genes Conferring Colistin Resistance in Enterobacterales; a Five Year Overview". Acta Medica Academica. 50 (3): 365–371. doi:10.5644/ama2006-124.355. PMID 35164512. S2CID 246826086.

- ^ Napier BA, Burd EM, Satola SW, Cagle SM, Ray SM, McGann P, et al. (May 2013). "Clinical use of colistin induces cross-resistance to host antimicrobials in Acinetobacter baumannii". mBio. 4 (3): e00021 – e00013. doi:10.1128/mBio.00021-13. PMC 3663567. PMID 23695834.

- ^ Jangir PK, Ogunlana L, Szili P, Czikkely M, Shaw LP, Stevens EJ, et al. (April 2023). "The evolution of colistin resistance increases bacterial resistance to host antimicrobial peptides and virulence". eLife. 12: e84395. doi:10.7554/eLife.84395. PMC 10129329. PMID 37094804.

- ^ a b McKay B (6 March 2018). "Common 'Superbug' Found to Disguise Resistance to Potent Antibiotic". wsj.com. Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2018-04-03. Retrieved 1 Nov 2018.

- ^ El-Halfawy OM, Valvano MA (January 2015). "Antimicrobial heteroresistance: an emerging field in need of clarity". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 28 (1): 191–207. doi:10.1128/CMR.00058-14. PMC 4284305. PMID 25567227.

- ^ a b Band VI, Satola SW, Burd EM, Farley MM, Jacob JT, Weiss DS (March 2018). "Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Exhibiting Clinically Undetected Colistin Heteroresistance Leads to Treatment Failure in a Murine Model of Infection". mBio. 9 (2): e02448–17. doi:10.1128/mBio.02448-17. PMC 5844991. PMID 29511071.

- ^ Markou N, Apostolakos H, Koumoudiou C, Athanasiou M, Koutsoukou A, Alamanos I, Gregorakos L (October 2003). "Intravenous colistin in the treatment of sepsis from multiresistant Gram-negative bacilli in critically ill patients". Critical Care. 7 (5): R78 – R83. doi:10.1186/cc2358. PMC 270720. PMID 12974973.

- ^ Wolinsky E, Hines JD (April 1962). "Neurotoxic and nephrotoxic effects of colistin in patients with renal disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 266 (15): 759–762. doi:10.1056/NEJM196204122661505. PMID 14008070.

- ^ Koch-Weser J, Sidel VW, Federman EB, Kanarek P, Finer DC, Eaton AE (June 1970). "Adverse effects of sodium colistimethate. Manifestations and specific reaction rates during 317 courses of therapy". Annals of Internal Medicine. 72 (6): 857–868. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-72-6-857. PMID 5448745.

- ^ Ledson MJ, Gallagher MJ, Cowperthwaite C, Convery RP, Walshaw MJ (September 1998). "Four years' experience of intravenous colomycin in an adult cystic fibrosis unit". The European Respiratory Journal. 12 (3): 592–594. doi:10.1183/09031936.98.12030592. PMID 9762785.

- ^ Li J, Nation RL, Milne RW, Turnidge JD, Coulthard K (January 2005). "Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 25 (1): 11–25. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.10.001. PMID 15620821.

- ^ Beringer P (November 2001). "The clinical use of colistin in patients with cystic fibrosis". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 7 (6): 434–440. doi:10.1097/00063198-200111000-00013. PMID 11706322. S2CID 38084953.

- ^ Conway SP, Etherington C, Munday J, Goldman MH, Strong JJ, Wootton M (November 2000). "Safety and tolerability of bolus intravenous colistin in acute respiratory exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 34 (11): 1238–1242. doi:10.1345/aph.19370. PMID 11098334. S2CID 42625124.

- ^ Littlewood JM, Koch C, Lambert PA, Høiby N, Elborn JS, Conway SP, et al. (July 2000). "A ten year review of colomycin". Respiratory Medicine. 94 (7): 632–640. doi:10.1053/rmed.2000.0834. PMID 10926333.

- ^ Stein A, Raoult D (October 2002). "Colistin: an antimicrobial for the 21st century?". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 35 (7): 901–902. doi:10.1086/342570. PMID 12228836.

- ^ Giacobbe DR, di Masi A, Leboffe L, Del Bono V, Rossi M, Cappiello D, et al. (August 2018). "Hypoalbuminemia as a predictor of acute kidney injury during colistin treatment". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 11968. Bibcode:2018NatSR...811968G. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30361-5. PMC 6086859. PMID 30097635.

- ^ Maddison J, Dodd M, Webb AK (February 1994). "Nebulized colistin causes chest tightness in adults with cystic fibrosis". Respiratory Medicine. 88 (2): 145–147. doi:10.1016/0954-6111(94)90028-0. PMID 8146414.

- ^ Kamin W, Schwabe A, Krämer I (December 2006). "Inhalation solutions: which one are allowed to be mixed? Physico-chemical compatibility of drug solutions in nebulizers". Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 5 (4): 205–213. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2006.03.007. PMID 16678502.

- ^ Domínguez-Ortega J, Manteiga E, Abad-Schilling C, Juretzcke MA, Sánchez-Rubio J, Kindelan C (2007). "Induced tolerance to nebulized colistin after severe reaction to the drug". Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 17 (1): 59–61. PMID 17323867.

- ^ Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL (September 2006). "Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 6 (9): 589–601. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1. PMID 16931410.

- ^ Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Smeaton TC, Coulthard K (May 2004). "Pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulphonate and colistin in rats following an intravenous dose of colistin methanesulphonate". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 53 (5): 837–840. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh167. PMID 15044428.

- ^ Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Smeaton TC, Coulthard K (May 2003). "Use of high-performance liquid chromatography to study the pharmacokinetics of colistin sulfate in rats following intravenous administration". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 47 (5): 1766–1770. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.5.1766-1770.2003. PMC 153303. PMID 12709357.

- ^ Koyama Y, Kurosasa A, Tsuchiya A, Takakuta K (1950). "A new antibiotic 'colistin' produced by spore-forming soil bacteria". J Antibiot (Tokyo). 3.

- ^ MacLaren G, Spelman D (22 November 2022). Hopper DC, Hall KK (eds.). "Colistin: An overview". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Archived from the original on 2016-05-31. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ^ Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK (May 2005). "Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 40 (9): 1333–1341. doi:10.1086/429323. PMID 15825037. S2CID 21679015.

- ^ Schoenmakers K (21 October 2020). "How China is getting its farmers to kick their antibiotics habit". Nature. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ Dewick PM (2009). Medicinal Natural Products (Third ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Further reading

[edit]- Reardon S (December 2015). "Spread of antibiotic-resistance gene does not spell bacterial apocalypse — yet". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.19037.

External links

[edit]- "Colistin topics page (bibliography)". Science.gov.