Aeromonas

| Aeromonas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Aeromonadales |

| Family: | Aeromonadaceae |

| Genus: | Aeromonas Stanier 1943 |

| Species | |

|

A. aquariorum | |

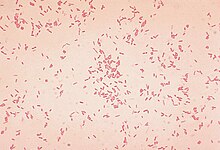

Aeromonas is a genus of Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, bacteria that morphologically resemble members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Most of the 14 described species have been associated with human diseases. The most important pathogens are A. hydrophila, A. caviae, and A. veronii biovar sobria. The organisms are ubiquitous in fresh and brackish water.[2]

They group with the gamma subclass of the Proteobacteria.[3]

Two major diseases associated with Aeromonas are gastroenteritis and wound infections, with or without bacteremia. Gastroenteritis typically occurs after the ingestion of contaminated water or food, whereas wound infections result from exposure to contaminated water. In its most severe form, Aeromonas spp. can cause necrotizing fasciitis, which is life-threatening, usually requiring treatment with antibiotics and even amputation.[4]

Although some potential virulence factors (e.g. endotoxins, hemolysins, enterotoxins, adherence factors) have been identified, their precise roles are unknown.[5][6]

Association with human diarrhea and human intestinal infections

[edit]Literature exists on this subject, but many papers have not adequately studied the causal role of the Aeromonas strain(s) that were isolated from the cases that were studied. The presence of an Aeromonas strain in a fecal specimen does not prove or even imply that the strain was causing the diarrhea. Gastrointestinal disease in children is usually an acute, severe illness, whereas that in adults tends to be chronic diarrhea. Severe Aeromonas gastroenteritis resembles shigellosis, with blood and leukocytes in the stool. Acute diarrheal disease is self-limited, and only supportive care is indicated in affected patients.

Wound infection

[edit]Wound infections are the second-most common type of human infection associated with Aeromonas.[7] They are associated with penetrating wounds or abrasions that place the wound in contact with fresh water or soil.[7]

Medicinal leeches

[edit]Aeromonas species are endosymbionts of Hirudo medicinalis, a species of leech that is FDA-approved for use in vascular surgery such as skin grafts and flaps.[8][9] Aeromonas aides leeches in digesting blood meals.[10] H. medicinalis used after surgery has led to Aeromonas infections, most commonly with A. veronii.[8] This can present as a local cellulitis, though can progress to subcutaneous abscess and sepsis.[8]

Respiratory infection

[edit]Aeromonas species have also been associated with pneumonia after near-drowning events, especially in fresh water.[11] Most commonly, this has been reported with A. hydrophila, though the ability of clinical laboratories to correctly identify species of Aeromonas has been limited.[11] Aeromonas pneumonia due to episodes of near-drowning are frequently complicated by bacteremia and death.[11]

Antimicrobial therapy

[edit]Aeromonas species are resistant to penicillins, most cephalosporins, and erythromycin. Ciprofloxacin is consistently active against their strains in the U.S. and Europe, but resistant cases have been reported in Asia. [citation needed]

Unchlorinated drinking-water supply

[edit][12] Aeromonas spp. are ubiquitous in river and freshwater lakes and have frequently been observed in drinking water systems. An interest in Aeromonas in nonchlorinated drinking water in the Netherlands was initiated from the 1980s, after the observation of a sudden increase of Aeromonas numbers in drinking water at the municipal Dune Waterworks of The Hague in 1984. Extensive studies with phenotyping and genotyping methods demonstrated that Aeromonas isolates from fresh and drinking water environments were phenotypically and genotypically different from Aeromonas isolates from patients. In response to these studies, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the United States removed Aeromonas from the contaminant candidate list (CCL) in 2009. In the Netherlands, the presence of Aeromonas in drinking water is currently not considered a health-related problem. Aeromonas is only a minor part (<0.01%) of the diverse autochthonous microflora. Drinking water companies limit the multiplication of bacteria, protozoans and invertebrates (all natural parts of drinking-water distribution systems [13]). The authorities in the Netherlands included Aeromonas in the Dutch Drinking Water Decree as an additional operational indicator (beside heterotrophic plate count [HPC]) for microbial regrowth, limited to 1,000 CFU/100 ml, obtained by growth on specific ampicillin-dextrin agar plates at 30 °C. When drinking water companies do not comply with this standard, they have to minimize the growth conditions. A recent study on indicator parameters for regrowth concluded that HPCs and aeromonads are more reliable indicators for regrowth in drinkwater distribution systems the Netherlands than ATP and bacterial cell numbers. Another field study in the Netherlands showed that noncompliance with the Aeromonas standard in two distribution systems coincided with increased HPCs (within the limits of the Dutch Drinking Water Decree), occasional coliform regrowth, and enhanced numbers of macroinvertebrates (e.g., water lice). Furthermore, it has been observed that Aeromonas isolates are mainly associated with sediment in the distribution system and to a lesser extent with drinking water, but not with the biofilm on the pipe wall, demonstrating that sediment or loose deposits (consisting of small and larger [in]organic and biological suspended solids, including invertebrates) are the main niche for Aeromonas. The results from these studies, thus, show that Aeromonas is still useful as a regrowth indicator in nonchlorinated drinking-water.

Etymology

[edit]The name Aeromonas derives from:

Greek aer, aeros (ἀήρ, ἀέρος), air, gas; and -monas|monas (μονάς), unit, monad; gas(-producing) monad.[14]

Members of the genus Aeromonas can be referred to as aeromonads (viz. trivialisation of names).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Parte, A. C. "Aeromonas". LPSN.

- ^ Graf J, ed. (2015). Aeromonas. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-908230-56-0.

- ^ Martinez-Murcia AJ, Benlloch S, Collins MD (July 1992). "Phylogenetic interrelationships of members of the genera Aeromonas and Plesiomonas as determined by 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing: lack of congruence with results of DNA-DNA hybridizations". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 42 (3): 412–21. doi:10.1099/00207713-42-3-412. PMID 1380289.

- ^ Minnaganti, Venkat R.; Patel, Pankaj J.; Iancu, Dan; Schoch, Paul E.; Cunha, Burke A. (2000). "Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Aeromonas hydrophila". Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care. 29 (4): 306–308. doi:10.1067/mhl.2000.106723. ISSN 0147-9563. PMID 10900069.

- ^ Ghenghesh, Khalifa Sifaw; Ahmed, Salwa F.; Cappuccinelli, Piero; Klena, John D. (2014-09-09). "Genospecies and virulence factors of Aeromonas species in different sources in a North African country". The Libyan Journal of Medicine. 9 (1): 10.3402/ljm.v9.25497. doi:10.3402/ljm.v9.25497. ISSN 1993-2820. PMC 4161726. PMID 25216211.

- ^ Igbinosa, Isoken H.; Igumbor, Ehimario U.; Aghdasi, Farhad; Tom, Mvuyo; Okoh, Anthony I. (2012-06-04). "Emerging Aeromonas Species Infections and Their Significance in Public Health". The Scientific World Journal. 2012: 625023. doi:10.1100/2012/625023. ISSN 2356-6140. PMC 3373137. PMID 22701365.

- ^ a b Parker, Jennifer L.; Shaw, Jonathan G. (2011). "Aeromonas spp. clinical microbiology and disease". Journal of Infection. 62 (2): 109–118. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2010.12.003. PMID 21163298.

- ^ a b c Whitaker, Iain S.; Kamya, Cyril; Azzopardi, Ernest A.; Graf, Joerg; Kon, Moshe; Lineaweaver, William C. (1 November 2009). "Preventing infective complications following leech therapy: Is practice keeping pace with current research?" (PDF). Microsurgery. 29 (8): 619–625. doi:10.1002/micr.20666. ISSN 1098-2752. PMID 19399888. S2CID 19575531. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ "FDA approves leeches as medical devices". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Aeromonas-Hirudo medicinalis symbiosis". sp.uconn.edu. Archived from the original on 26 September 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Ender, Peter T.; Dolan, Matthew J. (1 October 1997). "Pneumonia Associated with Near-Drowning". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 25 (4): 896–907. doi:10.1086/515532. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 9356805.

- ^ Nikki van Bel, Paul van der Wielen, Bart Wullings, Jeroen van Rijn, Ed van der Mark, Henk Ketelaars, Wim Hijnen (2021) Aeromonas Species from Nonchlorinated Distribution Systems and Their Competitive Planktonic Growth in Drinking Water https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/AEM.02867-20

- ^ Van Lieverloo, J.H.M., Van der Kooij, D. and Hoogenboezem, W. (2002). ‘Invertebrates and Protozoa (Free-living) in Drinking Water Distribution Systems’. In: Bitton, G. (ed.). ‘Encyclopedia of Environmental Microbiology’. John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 1718-1733. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Encyclopedia+of+Environmental+Microbiology%2C+6+Volume+Set-p-9780471354505)

- ^ Aeromonas in LPSN; Parte, Aidan C.; Sardà Carbasse, Joaquim; Meier-Kolthoff, Jan P.; Reimer, Lorenz C.; Göker, Markus (1 November 2020). "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 70 (11): 5607–5612. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004332.

Further reading

[edit]- Walker, S. J. (2003). "Aeromonas". In Benjamin Caballero (ed.). Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. Oxford: Academic Press. pp. 62–65. doi:10.1016/B0-12-227055-X/00015-8. ISBN 9780122270550.

- Janda, J. M.; Abbott, S. L. (2010). "The Genus Aeromonas: Taxonomy, Pathogenicity, and Infection". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23 (1): 35–73. doi:10.1128/CMR.00039-09. PMC 2806660. PMID 20065325.