Kishinev pogrom

47°02′15″N 28°48′16″E / 47.0376°N 28.8045°E

| Kishinev pogrom | |

|---|---|

| Part of the pogroms in the Russian Empire | |

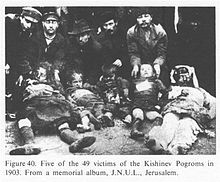

Bodies in the street | |

| Location | Kishinev, Bessarabia Governorate, Russian Empire (now Chișinău, Moldova) |

| Date | 19–21 April [O.S. 6–8 April] 1903 |

| Target | Bessarabian Jews |

Attack type | |

| Deaths | 49 |

| Injured | 92 gravely injured >500 lightly injured |

| Perpetrators | Russian pogromists |

| Motive | Antisemitism |

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on 19–21 April [O.S. 6–8 April] 1903.[1] During the pogrom, which began on Easter Day, 49 Jews were killed, 92 were gravely injured, a number of Jewish women were raped, over 500 were lightly injured and 1,500 homes were damaged.[2][3] American Jews began large-scale organized financial help, and assisted in emigration.[4] The incident focused worldwide attention on the persecution of Jews within the Russian Empire,[5] and led Theodor Herzl to propose the Uganda Scheme as a temporary refuge for the Jews.[6]

A second pogrom erupted in the city in October 1905.[7]

History

[edit]

The most popular newspaper in Kishinev (now Chișinău), the Russian-language anti-Semitic newspaper Бессарабец (Bessarabets, meaning "Bessarabian"), published by Pavel Krushevan, regularly published articles with headlines such as "Death to the Jews!" and "Crusade against the Hated Race!" (referring to the Jews).[citation needed] When a Ukrainian boy, Mikhail Rybachenko, was found murdered in the town of Dubăsari, about 40 km (25 mi) north of Kishinev, and a girl who committed suicide by poisoning herself was declared dead in a Jewish hospital, the Bessarabetz paper insinuated that both children had been murdered by the Jewish community for the purpose of using their blood in the preparation of matzo for Passover.[8] Another newspaper, Свет (Svet, "Light") made similar insinuations. These allegations sparked the pogrom.[7]

The pogrom began on April 19 (April 6 according to the Julian calendar, then in use in the Russian Empire) after congregations were dismissed from church services on Easter Sunday. In two days of rioting, 47 (some put the figure at 49) Jews were killed, 92 were severely wounded and 500 were slightly injured, 700 houses were destroyed, and 600 stores were pillaged.[7][9] The Times published a forged dispatch by Vyacheslav von Plehve, the Minister of Interior, to the governor of Bessarabia, which supposedly gave orders not to stop the rioters.[10] Unlike the more responsible authorities at Dubăsari, who acted to prevent the pogrom, there is evidence that the officials in Kishinev acted in collusion or negligence, turning a blind eye to the impending pogrom.[7][11]

On 28 April, The New York Times reprinted a Yiddish Daily News report that was smuggled out of Russia:[4]

The mob was led by priests, and the general cry, "Kill the Jews", was taken-up all over the city. The Jews were taken wholly unaware and were slaughtered like sheep. The dead number 120 and the injured about 500. The scenes of horror attending this massacre are beyond description. Babes were literally torn to pieces by the frenzied and bloodthirsty mob. The local police made no attempt to check the reign of terror. At sunset the streets were piled with corpses and wounded. Those who could make their escape fled in terror, and the city is now practically deserted of Jews.[12]

The Kishinev pogrom of 1903 captured the attention of the international public and was mentioned in the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine as an example of the type of human rights abuse which would justify United States involvement in Latin America. The 1904 book The Voice of America on Kishinev provides more detail[13] as does the book Russia at the Bar of the American People: A Memorial of Kishinef.[14]

Russian response

[edit]

The Russian ambassador to the United States, Count Arthur Cassini, characterised the 1903 pogrom as a reaction of financially hard-pressed peasants to Jewish creditors in an interview on 18 May 1903:

The situation in Russia, so far as the Jews are concerned is just this: It is the peasant against the money lender, and not the Russians against the Jews. There is no feeling against the Jew in Russia because of religion. It is as I have said—the Jew ruins the peasants, with the result that conflicts occur when the latter have lost all their worldly possessions and have nothing to live upon. There are many good Jews in Russia, and they are respected. Jewish genius is appreciated in Russia, and the Jewish artist honoured. Jews also appear in the financial world in Russia. The Russian Government affords the same protection to the Jews that it does to any other of its citizens, and when a riot occurs and Jews are attacked the officials immediately take steps to apprehend those who began the riot, and visit severe punishment upon them."[15]

There is a memorial to the 1903 pogrom in modern Kishinev.[16]

Aftermath

[edit]American media mogul William Randolph Hearst "adopt[ed] Kishinev as little less than a crusade", according to Stanford historian Steven Zipperstein.[17] As part of this publicity, Hearst sent the Irish nationalist journalist Michael Davitt to Kishinev as "special commissioner to investigate the massacres of the Jews", becoming one of the first foreign journalists to report on the pogrom.[18][17]

Due to their involvement in the pogrom, two men were sentenced to seven and five years' imprisonment respectively, and a further 22 were sentenced to one or two years.

This pogrom was instrumental in convincing tens of thousands of Russian Jews to leave for the West or Palestine.[7] As such, it became a rallying point for early Zionists, especially what would become Revisionist Zionism, inspiring early self-defense leagues under leaders like Ze'ev Jabotinsky.[7]

-

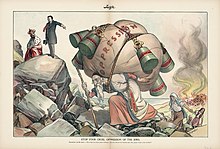

Imprinting honoring the "Kishinev Martyrs", by Ephraim Moses Lilien.

-

A rejected petition to the Tsar of Russia by US citizens, 1903, now kept at the US National Archives

1905 pogrom

[edit]A second pogrom took place in Kishinev on 19–20 October 1905. This time, the riots began as political protests against the Tsar, but turned into an attack on Jews wherever they could be found. By the time the riots were over, 19 Jews had been killed and 56 were injured. Jewish self-defense leagues, organized after the first pogrom, stopped some of the violence, but were not wholly successful. This pogrom was part of a series of pogroms that swept the Russian Empire at the time.

Cultural references

[edit]

Russian authors such as Vladimir Korolenko wrote about the pogrom in House 13, while Tolstoy and Gorky wrote condemnations blaming the Russian government—a change from the earlier pogroms of the 1880s, when most members of the Russian intelligentsia were silent. Tolstoy worked with Sholem Aleichem to produce an anthology dedicated to the victims, with all publisher and author proceeds going to relief efforts, which became the work "Esarhaddon, King of Assyria".[19][20] Sholem Aleichem went on to write the material for the famous Fiddler on the Roof.

It also had a major impact on Jewish art and literature. After interviewing survivors of the Kishinev pogrom, the Hebrew poet Chaim Bialik (1873–1934) wrote "In the City of Slaughter," about the perceived passivity of the Jews in the face of the mobs.[5] Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who was also in the city after the massacre, translated Bialik's poem into Russian, thereby contributing to both the publication of the poem and Bialik's fame in Russian-speaking countries.[21][22] In the 1908 play by Israel Zangwill titled The Melting Pot, the Jewish hero emigrates to America in the wake of the Kishinev pogrom, eventually confronting the Russian officer who led the rioters.[23]

More recently, Joann Sfar's series of graphic novels titled Klezmer depicts life in Odessa, Ukraine, at this time; in the final volume (number 5), Kishinev-des-fous, the first pogrom affects the characters.[24] Playwright Max Sparber took the Kishinev pogrom as the subject for one of his earliest plays in 1994.[25] The novel The Lazarus Project by Aleksander Hemon (2008) provides a vivid description of the pogrom and details its long-reaching consequences.[26]

In Brazil, the Jewish writer Moacyr Scliar wrote the fiction and social satire book "O Exército De Um Homem Só" (1986), about Mayer Guinzburg, a Brazilian-Jew and Communist activist whose family are refugees from the Kishinev pogrom.

Monument to victims

[edit]

The Victims of the Chișinău Pogrom Monument (Romanian: Monumentul Victimelor Pogromului de la Chișinău) is a memorial stone to the victims of the Kishinev pogrom, unveiled in 1993 in Alunelul park, Chișinău, Moldova.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Penkower, Monty Noam (October 2004). "The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903: A Turning Point in Jewish History". Modern Judaism. 24 (3). Oxford University Press: 187–225. doi:10.1093/mj/kjh017.

- ^ "The pogrom that transformed 20th century Jewry". The Harvard Gazette. 9 April 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Chicago Jewish Cafe (20 September 2018). "Are Jewish men cowards? Conversation with Prof. Steven J. Zipperstein". YouTube. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ a b Schoenberg, Philip Ernest (1974). "The American Reaction to the Kishinev Pogrom of 1903". American Jewish Historical Quarterly. 63 (3): 262–283. ISSN 0002-9068. JSTOR 23877915.

- ^ a b Corydon Ireland (9 April 2009). "The pogrom that transformed 20th century Jewry". The Harvard Gazette.

- ^ Birnbaum, Erwin. In the Shadow of the Struggle. Accessed 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Davitt, Michael (1903). Within The Pale. London: Hurst and Blackett. pp. 98–100.

- ^ The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903; with online resources archived from www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org; archive accessed 27 January 2022

- ^ Klier, John (October 11, 2010). "Pogroms". YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ Klier, John Doyle; Lambroza, Shlomo (1992). Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-521-52851-1.

- ^ "Jewish Massacre Denounced". The New York Times. 28 April 1903. p. 6.

- ^ Adler, Cyrus (ed.). The Voice of America on Kishineff. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Singer, Isidore (1904). Russia at the Bar of the American People. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "Current Literature: A Magazine of Contemporary Record (New York). Vol. XXXV., No.1. July, 1903. Current Opinion. V.35 (1903). p. 16". babel.hathitrust.org. pp. 25 v.

- ^ "Picasa Web Albums - Ronnie - kishinev". Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ a b Zipperstein 2015, p. 372.

- ^ Beatty 2017, p. 125.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy (2015). R. F. Christian (ed.). Tolstoy's Diaries. Vol. 2: 1895–1910. Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780571324064.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy (1906). Tolstoy on Shakespeare: A Critical Essay on Shakespeare. Translated by Isabella Fyvie Mayo, Vladimir Grigorʹevich Chertkov. Funk & Wagnalls Company.

- ^ Holtzman, Avner; Scharf, Orr (2017). Hayim Nahman Bialik: poet of Hebrew. Jewish lives. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-300-20066-9. OCLC 953985607.

- ^ "מכון ז'בוטינסקי | Item". en.jabotinsky.org. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Zangwill, Israel (2006). From the Ghetto to the Melting Pot: Israel Zangwill's Jewish Plays : Three Playscripts. Wayne State University Press. p. 254. ISBN 9780814329559. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Weingrad, Michael (Spring 2015). "Drawing Conclusions: Joann Sfar and the Jews of France". Jewish Review of Books. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Sparber, Max (3 December 2014). "Staged reading of play by Max Sparber: Kishinev". MetaFilter. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Hemon, A., (2008). The Lazarus project. New York: Riverhead Books

- ^ "Chisinau. Monument to Pogrom Victims". jewishmemory.md. 24 April 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Beatty, Aidan (2017). "Jews and the Irish nationalist imagination: between philo-Semitism and anti-Semitism". Journal of Jewish Studies. 68 (1): 125–128. doi:10.18647/3304/JJS-2017.

- Zipperstein, Steven J. (2015). "Inside Kishinev's Pogrom: Hayyim Nahman Bialik, Michael Davitt, and the Burdens of Truth" (PDF). In Freeze, ChaeRan Y.; Fried, Sylvia Fuks; Sheppard, Eugene R. (eds.). The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz. Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press. ISBN 9781611687330.

Further reading

[edit]- Judge, Edward H. Easter in Kishinev: Anatomy of a Pogrom. NYU Press 1992.

- Penkower, Monty Noam (2004). "The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903: A Turning Point in Jewish History". Modern Judaism. 24 (3): 187–225. doi:10.1093/mj/kjh017. JSTOR 1396539. S2CID 170968039.

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Schoenberg, Philip Ernest. "The American Reaction to the Kishinev Pogrom of 1903". American Jewish Historical Quarterly 63.3 (1974): 262–283.

- Zipperstein, Steven J. Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History. Liveright Publishing March 2018.

- "YIVO | Kishinev". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

External links

[edit]- Kishinev Pogrom unofficial commemorative website

- Resources about the pogrom

- "Are Jewish men cowards?" Interview in Chicago Jewish Cafe with Prof. Steven Zipperstein, the author of "Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History."