The Holocaust in Belgium

The Holocaust in Belgium was the systematic dispossession, deportation, and murder of Jews and Roma in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. Out of about 66,000 Jews in the country in May 1940, around 28,000 were murdered during the Holocaust.[1]

At the start of the war, the population of Belgium was overwhelmingly Catholic. Jews made up the largest non-Christian population in the country, numbering between 70–75,000 out of a population of 8 million. Most lived in the cities of Antwerp, Brussels, Charleroi and Liège. The vast majority were recent immigrants to Belgium who had fled persecution in Germany and Eastern Europe, and, as a result, only a small minority actually possessed Belgian citizenship.

Shortly after the invasion of Belgium, the Military Government passed a series of anti-Jewish laws in October 1940. The Belgian Committee of Secretaries-General refused from the start to co-operate on passing any anti-Jewish measures and the Military Government seemed unwilling to pass further legislation. The German government began to seize Jewish-owned businesses and forced Jews out of positions in the civil service. In April 1941, without orders from the German authorities, Flemish collaborators pillaged two synagogues in Antwerp and burned the house of the chief rabbi of the town in the Antwerp Pogrom. The Germans created a Judenrat in the country, the Association des Juifs en Belgique (AJB; "Association of Jews in Belgium"), which all Jews were required to join. As part of the Final Solution from 1942, the persecution of Belgian Jews escalated. From May 1942, Jews were forced to wear yellow Star of David badges to mark them out in public. Using the registers compiled by the AJB, the Germans began deporting Jews to concentration camps in Poland. Jews chosen from the registration lists were required to turn up at the newly established Mechelen transit camp; they were then deported by train to concentration camps, mostly to Auschwitz. Between August 1942 and July 1944, around 25,500 Jews and 350 Roma were deported from Belgium; more than 24,000 were killed before the camps were liberated by the Allies.

From 1942, opposition among the general population to the treatment of the Jews in Belgium grew. By the end of the occupation, more than 40 per cent of all Jews in Belgium were in hiding; many of them were hidden by Gentiles, particularly by Catholic priests and nuns. Some were helped by the organized resistance, such as the Comité de Défense des Juifs (CDJ; "Committee of Jewish Defense"), which provided food and refuge to hiding Jews. Many of the Jews in hiding joined the armed resistance. In April 1943, members of the CDJ attacked the twentieth rail convoy to Auschwitz and succeeded in rescuing some of those being deported.

Background

[edit]Religion and Anti-Semitism

[edit]

Before the war, the population of Belgium was overwhelmingly Catholic. Around 98 per cent of the population was baptized and around 80 per cent of marriage ceremonies were held with traditional Catholic services, while politically the country was dominated by the Catholic Party.[2]

The Jewish population of Belgium was comparatively small. Out of a population of around 8 million, there were only 10,000 Jews in the country before World War I.[3] The interwar period saw substantial Jewish immigration to Belgium. By 1930, the population rose to 50,000, and by 1940 it was between 70,000–75,000.[3] Most of the new Jewish immigrants came from Eastern Europe and Nazi Germany, escaping anti-Semitism and poverty in their native countries.[3] The Roma population of Belgium at the same time was approximately 530.[4] Few of the Jewish migrants claimed Belgian citizenship, and many did not speak French or Dutch. Jewish communities developed in Charleroi, Liège, Brussels and, above all, Antwerp, where more than half of the Jews in Belgium lived.[3]

The Interwar period also saw the rise in popularity of Fascist New Order parties in Belgium. These were chiefly represented by the Vlaams Nationaal Verbond (VNV; "Flemish National Union") and Verdinaso in Flanders, and Rex in Wallonia. Both Flemish parties supported the creation of an ethnically Germanic "Dietse Natie" ("Greater Dutch State") from which Jews would be excluded.[5] Rex, whose ideology was based on Christian Fascism, was particularly anti-Semitic, but both VNV and Rex campaigned under anti-Semitic slogans for the 1938 elections.[6] Their stance was officially condemned by the Belgian authorities, but prominent figures, including King Leopold III, were suspected of holding anti-Semitic attitudes.[7] From June 1938, Jewish illegal immigrants arrested by the Belgian police were deported to Germany, until public condemnation halted the practice after Kristallnacht in November 1938.[8] Between 1938 and the start of the war, with the influence of Fascist parties declining in Belgium, the country began accepting more Jewish refugees, including 215 from the MS St. Louis who had been refused visas elsewhere.[9]

German invasion and occupation

[edit]In the interwar period, Belgium followed a strict policy of political neutrality. Though the Belgian Army was mobilized in 1939, the country only became involved in the war on 10 May 1940, when it was invaded by Nazi Germany. After a campaign lasting 18 days, the Belgian military, along with its commander-in-chief Leopold III, surrendered on 28 May. Belgium, together with the French province of Nord-Pas-de-Calais, were grouped together under the German Military Administration in Belgium and Northern France (Militärverwaltung in Belgien und Nordfrankreich). Because the country was under military occupation, it initially fell under the control of the Wehrmacht rather than Nazi Party or Schutzstaffel (SS) authorities. In July 1944, the Militärverwaltung was replaced with a civilian administration (Zivilverwaltung), greatly increasing the power of the more radical Nazi Party and SS organisations until the Allied liberation in September 1944.

The Holocaust

[edit]Early discrimination and persecution, 1940–41

[edit]

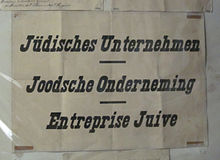

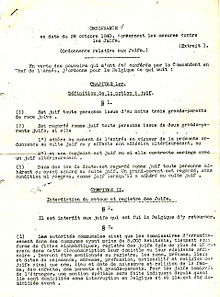

On 23 October 1940, the German Military Administration adopted anti-Jewish legislation for the first time.[10] The new laws, similar to the Nuremberg Laws adopted in Germany in 1935, coincided with the adoption of similar legislation in the Netherlands and in France.[10] The laws of 28 October forbade Jews to practice certain professions (including the civil service) and forced Jews to register with their local municipality.[11] On the same date, the German administration announced a definition of who was regarded as Jewish. Jewish-owned shops or businesses had to be marked by a sign in the window, and Jewish-owned economic assets had to be registered.[11] From June 1940, a list of Jewish businesses had already been drawn up in Liège.[12]

In 1940, the German government began to liquidate Jewish businesses. Some were transferred to German ownership in a process termed Aryanization.[13] Some 6,300 Jewish-owned businesses were liquidated before 1942, and 600 were Aryanized.[14] Around 600 million Belgian francs was raised from the seizures, much less than anticipated.[13][15] In total, between 28 October 1940 and 21 September 1942, 17 anti-Jewish ordinances were proclaimed by the Military Administration.[16]

Association des Juifs en Belgique

[edit]The "Association of Jews in Belgium" (AJB) was a Judenrat created by the Germans to administer the Jewish population of Belgium from November 1941.[17] Though directed by the Germans, the AJB was run by Jews and acted as an "organizational ghetto", allowing the Nazis to deal with Belgian Jews as a unit.[18] The AJB played a major role in registering Jews in the country. In total, 43,000 Jews were registered with the AJB.[14] This number represents only half of the total Jewish population, reflecting the community's mistrust of the organization, but it was the figure that SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann presented as the total number of Jews in Belgium at the Wannsee Conference in January 1942.[19]

During the deportations, around 10,000 Jews were arrested based on their affiliation to the AJB.[20] The AJB, closely supervised by the SiPo-SD (Sicherheitspolizei und Sicherheitsdienst; "Security Police and Intelligence Service"), was also responsible for the administration of the transit camp at Mechelen.[20] The AJB played a major role in persuading Jews to turn up voluntarily for deportation, though whether they knew the fate awaiting the deportees is disputed.[18] From 1942, following the assassination by the Resistance of Robert Holzinger, an AJB leader, confidence in the association declined and it was regarded with increasing suspicion.[15]

After the war, the leaders of the AJB were tried and acquitted of complicity in the Holocaust.[18]

Radicalisation, 1941–42

[edit]Antwerp Pogrom and Yellow Badge

[edit]

On 14 April 1941, after watching the German propaganda film Der Ewige Jude, Flemish paramilitaries from the Volksverwering, VNV and Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen began a pogrom in the city of Antwerp.[21] The mob, armed with iron bars, attacked and burned two synagogues in the city and threw the Torah scrolls onto the street.[21] They then attacked the home of Marcus Rottenburg, the town's chief rabbi. The police and fire brigade were summoned, but they were forbidden to intervene by the German authorities.[21]

As in the rest of occupied Europe, compulsory wearing of the yellow badge was enforced from 27 May 1942.[22] The Belgian version of the badge depicted a black letter "J" (standing for "Juif" in French and "Jood" in Dutch) in the centre of a yellow star of David. The star had to be displayed prominently on all outer clothing when in public and there were harsh penalties for non-compliance. The decree sparked public outrage in Belgium.[22] At great personal risk, the Belgian civil authorities in Brussels and Liège refused to distribute the badge, buying time for many Jews to go into hiding.[23]

The German authorities in Antwerp attempted to enforce the wearing of badges in 1940, but the policy was dropped when non-Jewish citizens protested and wore the armbands themselves.[24]

Deportation and extermination, 1942–44

[edit]From August 1942, the Germans began deporting Jews, using Arbeitseinsatz ("recruitment for work") in German factories as a pretext.[15] Around half of the Jews turned up voluntarily (though coerced by the German authorities) for transportation although round-ups were begun in late July. Later in the war, the Germans increasingly relied on the police to arrest or round up Jews by force.[25]

The first convoy from Belgium, carrying stateless Jews, left Mechelen transit camp for Auschwitz on 4 August 1942 and was soon followed by others.[26] These trains left for extermination camps in Eastern Europe. Between October 1942 and January 1943, deportations were temporarily halted;[27] by this time 16,600 people have been deported on 17 rail convoys.[15] As the result of Queen Elisabeth's intervention with the German authorities, all of those deported in this first wave were not Belgian citizens.[27] In 1943, the deportations resumed. By the time that deportations to extermination camps had begun, however, nearly 2,250 Belgian Jews had already been deported as forced laborers for Organisation Todt, a civil and military engineering group, which was working on the construction of the Atlantic Wall in Northern France.[26]

In September, armed Devisenschutzkommando (DSK; "Currency protection command") units raided homes to seize valuables and personal belongings as the occupants were preparing to report to the transit camp, and in the same month, Jews with Belgian citizenship were deported for the first time.[27] DSK units relied on networks of informants, who were paid between 100 and 200 Belgian francs for each person they betrayed.[28] After the war, the collaborator Felix Lauterborn stated in his trial that 80 per cent of arrests in Antwerp used information from paid informants.[29] In total, 6,000 Jews were deported in 1943, with another 2,700 in 1944. Transports were halted by the deteriorating situation in occupied Belgium before the liberation.[30]

The percentages of Jews which were deported varied by location. It was highest in Antwerp, with 67 per cent deported, but lower in Brussels (37 per cent), Liège (35 per cent) and Charleroi (42 per cent).[31] The main destination for the convoys was Auschwitz in German-occupied Poland. Smaller numbers were sent to Buchenwald and Ravensbrück concentration camps, as well as Vittel concentration camp in France.[30]

In total, 25,437 Jews were deported from Belgium.[30] Only 1,207 of these survived the war.[32] Amongst those deported and killed was the surrealist artist Felix Nussbaum in 1944.

Belgian collaboration in the Holocaust

[edit]

Political collaboration

[edit]Some assistance was provided to the German authorities in the persecution of Belgian Jews by members of collaborationist political groups, either out of overt anti-Semitic sentiment or the desire to demonstrate their loyalty to the German authorities. The deportations were encouraged by the VNV and the Algemeene-SS Vlaanderen in Flanders and both, like Rex, published anti-Semitic articles in their party newspapers.[33]

An association known as Défense du Peuple/Volksverwering ("The People's Defence") was specially formed to bring together Belgian anti-Semites and to assist in the deportations.[33] During the early stages of the occupation, they campaigned for harsher anti-Jewish laws.[34]

Administrative collaboration

[edit]The German occupation authorities made use of the surviving infrastructure of the pre-war state including the Belgian civil service, police and Gendarmerie. These were officially forbidden by their superiors to assist the German authorities in anything other than routine maintenance of law and order. However, there were numerous incidents in which individual policemen or local sections assisted in the German arrest of Jews in breach of their orders.[35] In Antwerp, the Belgian authorities facilitated the conscription of Jews for forced labour in France in 1941[25] and aided in the rounding up of Jews in August 1942 after the SiPo-SD threatened to imprison local officials in Fort Breendonk.[35] Outside Antwerp, the Germans used coercion to force the Belgian police to intervene, and in Brussels at least three police officers disobeyed orders and helped arrest Jews.[35] The historian Insa Meinen argued that around a fifth of the Jews arrested in Belgium were rounded up by the Belgian policemen.[25] Nevertheless, the general refusal of the Belgian police to assist in the Holocaust has been cited as a reason for the comparatively high survival rate of Belgian Jews during the Holocaust.[35]

Belgian opposition to Jewish persecution

[edit]Belgian resistance to the treatment of Jews crystallised between August–September 1942, following the passing of legislation regarding wearing yellow badges and the start of the deportations.[36] When deportations began, Jewish partisans destroyed records of Jews compiled by the AJB.[15] The first organization specifically devoted to hiding Jews, the Comité de Défense des Juifs (CDJ-JVD), was formed in the summer of 1942.[36] The CDJ, a left-wing organization, may have saved up to 4,000 children and 10,000 adults by finding them safe hiding places.[37] It produced two Yiddish language underground newspapers, Unzer Wort (אונזער-ווארט, "Our Word", with a Labour-Zionist stance) and Unzer Kamf (אונזער קאמף, "Our Fight", with a Communist one).[38] The CDJ was only one of dozens of organised resistance groups that provided support to hidden Jews. Other groups and individual resistance members were responsible for finding hiding places and providing food and forged papers.[30] Many Jews in hiding went on to join organised resistance groups. Groups from left wing backgrounds, like the Front de l'Indépendance (FI-OF), were particularly popular with Belgian Jews. The Communist-inspired Partisans Armés (PA) had a particularly large Jewish section in Brussels.[39]

The resistance was responsible for the assassination of Robert Holzinger, the head of the deportation program, in 1942.[26] Holzinger, an active collaborator, was an Austrian Jew selected by the Germans for the role.[26] The assassination led to a change in leadership of the AJB. Five Jewish leaders, including the head of the AJB, were arrested and interned in Breendonk, but were released after public outcry.[15] A sixth was deported directly to Auschwitz.[15]

The Belgian resistance was unusually well informed on the fate of the deported Jews. In August 1942 (two months after the start of the Belgian deportations), the underground newspaper De Vrijschutter reported that "They [the deported Jews] are being killed in groups by gas, and others are killed by salvos of machinegun fire."[40]

In early 1943, the Front de l'Indépendance sent Victor Martin, an academic economist at the Catholic University of Louvain, to gather information on the fate of deported Belgian Jews using the cover of his research post at the University of Cologne.[41] Martin visited Auschwitz and witnessed the crematoria. Arrested by the Germans, he escaped, and was able to report his findings to the CDJ in May 1943.[41]

Attack on the 20th transport

[edit]

The best-known Belgian resistance action during the Holocaust was the attack on the 20th rail convoy to Auschwitz.[27] In the evening of 19 April 1943, three poorly armed members of the resistance attacked the railway convoy as it passed near Haacht in Flemish Brabant.[43] The train, containing over 1,600 Jews, was guarded by 16 Germans from the SiPo-SD.[37] Resistance members used a lantern covered with red paper (a danger signal) to stop the train, and freed 17 prisoners from one wagon before they were discovered by the Germans.[37] A further 200 managed to jump from the train later in the journey, as the train's Belgian driver deliberately kept his speed low to allow others to escape.[37] All three resistance members responsible for the attack were arrested before the end of the occupation. Youra Livchitz was executed and Jean Franklemon and Robert Maistriau were deported to concentration camps but survived the war.[37]

The attack on the 20th train was the only attack on a Holocaust train from Belgium during the war, as well as the only transport from Belgium to experience a mass breakout.[37]

Passive resistance

[edit]The treatment of Jews by the Germans led to public resistance in Belgium. In June 1942, the representative of the German Foreign Ministry in Brussels, Werner von Bargen, complained the Belgians did not exhibit "sufficient understanding" of Nazi racial policy.[26]

The Belgian underground newspaper La Libre Belgique called for Belgian citizens to make small gestures to show their disgust at the Nazi racial policy. In August 1942, the paper called for Belgians to "Greet them [the Jews] in passing! Offer them your seat on the tram! Protest against the barbaric measures that are being applied to them. That'll make the Boches furious!"[44]

Discrimination against Jews was condemned by many high-profile figures in the occupied country. As early as October 1940, the senior Catholic clergyman in Belgium, Cardinal Jozef-Ernest van Roey, condemned the German policy and particularly the legislation from 1942.[45]

Van Roey made many of the church's resources available for hiding Jews, but was prevented from publicly condemning the treatment of the Jews by his peers, who feared a Nazi repression of the Church. German attempts to involve the Belgian authorities and local government in its implementation began to arouse protest from 1942. The Committee of Secretaries-General, a panel of Belgian senior civil servants tasked with implementing German demands, refused from the outset to enforce anti-Jewish legislation.[46] In June 1942, a conference of the 19 mayors of the Greater Brussels region refused to allow its officials to distribute yellow badges to Jews in their districts.[23] At great personal risk, the mayors, led by Joseph Van De Meulebroeck, sent a letter protesting the decree to the German authorities on 5 June.[23] The refusal of Brussels' council, and later that of the city of Liège, to distribute badges allowed many Jews to go into hiding before the deportations began.[47]

In the same year, members of the AJB met with Queen Elisabeth to appeal for her support against the deportations. She appealed to the Military Governor of Belgium, General Alexander von Falkenhausen, who sent Eggert Reeder, his deputy and head of the non-military aspects of the administration, to Berlin to clarify the policy with Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler. The SS-Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA; "Reich Main Security Office") made concessions to Elisabeth, allowing Jews with Belgian citizenship to be exempt from deportation, and Jewish families would not be broken up.[26] The RSHA also agreed not to deport Jewish men over the age of 65 and women over 60, after Belgian protests that they would be too old to be used as forced labor.[26]

Legacy and remembrance

[edit]In the aftermath of the war, emigration to Israel further decreased the Jewish population of Belgium, which as of 2011 was estimated at between 30,000 and 40,000.[48] The population is still concentrated in Brussels and Antwerp, but new smaller communities (such as those in Ghent, Knokke, Waterloo and Arlon) have developed since 1945.[48] Notable Belgian Holocaust survivors include Ilya Prigogine, a 1977 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, François Englert, a joint recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013, and Paul Lévy, a well-known journalist (who converted to Christianity) who was also responsible for the design of the European flag.

Since the passing of the Holocaust denial law in 1995, it is illegal to deny or attempt to justify the Holocaust.[49] The act follows the Belgian Anti-Racism Law, passed in 1981, which led to the establishment of the Centre for Equal Opportunities and Opposition to Racism, which researches racism and anti-Semitism in Belgium as well as aiding victims of discrimination.[50] Breendonk and Dossin Barracks (at the site of the former Mechelen transit camp) are preserved as museums to the Holocaust and to German repression in Belgium during the occupation.

In 2004, the Belgian Senate commissioned the Centre for Historical Research and Documentation on War and Contemporary Society (Cegesoma) to produce a definitive historical report on Belgian collaboration in the Holocaust.[51] The report, entitled "Docile Belgium" (La Belgique Docile/Gewillig België), was published in 2007. It generated significant public interest in Belgium and abroad.[51] The report's findings were controversial, as they emphasised the extent to which the Belgian police and authorities had collaborated in the deportation of Jews.[52]

As of 2013, a total of 1,612 Belgians have been awarded the distinction of Righteous Among the Nations by the State of Israel for risking their lives to save Jews from persecution during the occupation.[53]

Relatives of the victims have sought compensation from the state owned rail company SNCB after compensation was paid by the similar companies in France and the Netherlands. Between 1942 and 1943, SCNB chartered 28 convoys to transport prisoners from the Mechelen transit camp to Auschwitz. The director of the SCNB at the time was Narcisse Rulot who gave the explanation "I carry everything that comes, I do not look what is in the closed cars." His lackadaisical attitude and permissive complacency is seen to have contributed to the suffering and deaths of thousands. Though the company has apologized, the families of the victims continue to insist on compensation.[54]

See also

[edit]- Belgium in World War II

- History of the Jews in Belgium

- Jewish Museum of Belgium

- Henri Kichka

- Maxime Steinberg

References

[edit]- ^ "Belgium Historical Background". Yadvashem.org.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (1998). "The Attitudes of the Belgian Roman Catholic Clergy towards Jews prior to the Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 117. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b c d Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 160. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ Niewyk, Donald; Nicosia, Francis (2000). The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. Columbia: Columbia University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-231-11200-9.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 175. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 182–3. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ Van Eeckhaut, Fabien (13 September 2013). "Léopold III: Roi trop passif sous l'Occupation?". RTBF. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 184–5. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 187. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Maxime (1998). "The Judenpolitik in Belgium within the West European Context: Comparative Observations". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 200. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b Delplancq, Thierry. "Des paroles et des actes: L'administration bruxelloise et le registre des Juifs, 1940–1941" (PDF). Cegesoma. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Moore, Bob (Winter 2010). "The Fragility of Law: Constitutional Patriotism and the Jews of Belgium, 1940–1945 (review)". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 24 (3): 485. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcq059.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Maxime (1998). "The Judenpolitik in Belgium within the West European Context: Comparative Observations". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 201. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 343. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 394. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ "Présence juive dans nos régions". Musée Juif de Belgique. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Michman, Dan (1998). "Research on the Holocaust: Belgium and General". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 33. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b c Maron, Guy (10 November 2004). "Des Juifs, Curateurs du Ghetto Juif". Le Soir. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ Cesarani, David (2005) [2004]. Eichmann: His Life and Crimes. London: Vintage. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-09-944844-0.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Maxime (1998). "The Judenpolitik in Belgium within the West European Context: Comparative Observations". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 216. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b c Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 192–3. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b Van der Wijngaert, Mark (1998). "The Belgian Catholics and the Jews during the German Occupation, 1940–1944". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 229. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b c Saerens, Lieven (2012). "Insa Meinen: the Persecution of the Jews in Belgium through a German Lens". Journal of Belgian History (RBHC-BTNG). XLII (4): 204–5.

- ^ "Nazis in Belgium Revive Edict Imposing Yellow Badges on Jews". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Zürich. 3 June 1942. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Saerens, Lieven (2012). "Insa Meinen: the Persecution of the Jews in Belgium through a German Lens". Journal of Belgian History (RBHC-BTNG). XLII (4): 207.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 393. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ a b c d Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 435. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (2012). "Insa Meinen: the Persecution of the Jews in Belgium through a German Lens". Journal of Belgian History (RBHC-BTNG). XLII (4): 210.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (2008). De Jodenjagers van de Vlaamse SS. Lannoo. p. 188. ISBN 978-90-209-7384-6.

- ^ a b c d Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 436. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 194. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ Waterfield, Bruno (17 May 2011). "Nazi hunters call on Belgium's justice minister to be sacked". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b Saerens, Lieven (2012). "Insa Meinen: the Persecution of the Jews in Belgium through a German Lens". Journal of Belgian History (RBHC-BTNG). XLII (4): 212–4.

- ^ "Strict Anti-Jewish Laws in Belgium Demanded". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. London. 15 June 1941. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d Saerens, Lieven (2012). "Insa Meinen: the Persecution of the Jews in Belgium through a German Lens". Journal of Belgian History (RBHC-BTNG). XLII (4): 206.

- ^ a b Gotovich, José (1998). "Resistance Movements and the Jewish Question". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 274. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Williams, Althea; Ehrlich, Sarah (19 April 2013). "Escaping the train to Auschwitz". BBC News. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Various (1991). "Préface". Partisans Armés Juifs, 38 Témoignages. Brussels: Les Enfants des Partisans Juifs de Belgique.

- ^ Gotovich, José (1998). "Resistance Movements and the Jewish Question". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 281–2. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ Schreiber, Marion (2003). The Twentieth Train: the True Story of the Ambush of the Death Train to Auschwitz (1st US ed.). New York: Grove Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8021-1766-3.

- ^ a b Schreiber, Marion (2003). The Twentieth Train: the True Story of the Ambush of the Death Train to Auschwitz (1st US ed.). New York: Grove Press. pp. 73–5. ISBN 978-0-8021-1766-3.

- ^ Schreiber, Marion (2003). The Twentieth Train: the True Story of the Ambush of the Death Train to Auschwitz (1st US ed.). New York: Grove Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8021-1766-3.

- ^ Schreiber, Marion (2003). The Twentieth Train: the True Story of the Ambush of the Death Train to Auschwitz (1st US ed.). New York: Grove Press. pp. 220–3. ISBN 978-0-8021-1766-3.

- ^ "La Libre Belgique. 01-08-1942". Belgian War Press. Cegesoma. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (1998). "The Attitudes of the Belgian Roman Catholic Clergy towards Jews prior to the Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 156. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ Gotovitch, José; Aron, Paul, eds. (2008). Dictionnaire de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale en Belgique. Brussels: André Versaille éd. pp. 412–3. ISBN 978-2-87495-001-8.

- ^ Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 344. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ a b Rogeau, Olivier; Royen, Marie-Cécile (28 January 2011). "Juifs de Belgique" (PDF). Le Vif. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ "Projet de Loi tendant à réprimer la négation, la minimisation, la justification ou l'approbation du génocide commis par le régime national-socialiste allemand pendant la seconde guerre mondiale". lachambre.be. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ "Racial discrimination". Centre for Equal Opportunities and Opposition to Racism. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ a b Saerens, Lieven (2012). "Insa Meinen: the Persecution of the Jews in Belgium through a German Lens". Journal of Belgian History (RBHC-BTNG). XLII (4): 201–2.

- ^ Baes, Ruben. ""La Belgique docile". Les Autorités Belges et la Persécution des Juifs". Cegesoma. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ "The "Righteous Among the Nations" ceremony in the presence of President Shimon Peres, Prince Philippe and Minister Didier Reynders". Embassy of Belgium in Ireland. 5 March 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ "Relatives of Victims Seek Holocaust Compensation From Belgium's Railway". Algemeiner. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Meinen, Insa (2009). Die Shoah in Belgien (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 9783534221585. Also published in French and Dutch.

- Michman, Dan, ed. (1998). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- Steinberg, Maxime (1983). L'Étoile et le Fusil (in French). Vol. I: La Question Juive 1940–1942. Brussels: Éd. Vie Ouvrière. ISBN 2870031777.

- Steinberg, Maxime (1984). L'Étoile et le Fusil (in French). Vol. II: 1942. Les Cent Jours de la Déportation des Juifs de Belgique. Brussels: Éd. Vie Ouvrière. ISBN 2870031807.

- Steinberg, Maxime (1987). L'Étoile et le Fusil (in French). Vol. III: La Traque des Juifs 1942–1944. Brussels: Éd. Vie Ouvrière. ISBN 2870032102.

- Fraser, David (2009). The Fragility of Law: Constitutional Patriotism and the Jews of Belgium, 1940–1945. Abingdon: Routledge-Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-415-47761-1.

- Schreiber, Marion (2003). The Twentieth Train: the True Story of the Ambush of the Death Train to Auschwitz (1st US ed.). New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1766-3.

- Vromen, Suzanne (2008). Hidden Children of the Holocaust: Belgian Nuns and their Daring Rescue of Young Jews from the Nazis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195181289.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to The Holocaust in Belgium at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Holocaust in Belgium at Wikimedia Commons

- Belgium at the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI)

- Belgium at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM)