Chely Wright

Chely Wright | |

|---|---|

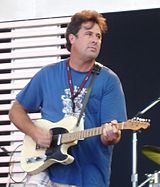

Wright in 2010 | |

| Born | Richell Rene Wright October 25, 1970 Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1993–present |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Lauren Blitzer (m. 2011) |

| Children | 2 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Website | chely |

Chely Wright (born Richell Rene Wright;[a] October 25, 1970)[3] is an American activist, author, and country music artist. She initially rose to fame as a commercial country recording artist with several charting singles, including the number one hit, "Single White Female." She later became known for her role in LGBT activism after publicly coming out as a gay woman in 2010. She has sold over 1,500,000 copies and 10,000,000 digital impressions to date in the United States.[4]

Raised in Kansas, Wright developed aspirations to become a country singer and songwriter. Yet, as a young child, she discovered her homosexuality and realized it conflicted with her Christian faith and her hopes of becoming a performer. Determined to become successful, she vowed to hide her sexuality and continued performing. Wright moved to Nashville, Tennessee, following high school graduation and was cast in stage productions at the now-defunct Opryland USA amusement park. She eventually signed her first recording contract in 1993 with PolyGram/Mercury Records and released two albums. With limited success, Wright switched record labels and had her first hit with 1997's "Shut Up and Drive". It was followed in 1999 with "Single White Female," and a gold-certified album of the same name.

At her commercial zenith, Wright continued living a closeted life and became increasingly unhappy. She engaged in a long-term relationship with a woman but ultimately separated at the risk of being outed by members of the Nashville community. In 2006, Wright began suffering an emotional collapse and nearly took her own life. She then realized she needed to come out publicly and started working on projects that would help her come to terms with her homosexuality. In 2010, Wright released the memoir, Like Me: Confessions of a Heartland Country Singer, and the album, Lifted Off the Ground. Both projects centered around her coming out process and the acceptance of herself.

Wright became involved in LGBT activism following her 2010 decision. During that time she moved to New York City and released a documentary which chronicled her coming out titled, Wish Me Away. She would later establish a charity "Like Me", which helped provide assistance to LGBT youth. She has since been a spokesperson for programs such as GLSEN. In recent years, she has held the role of Unispace's Diversity, Equity and Inclusion officer. Wright would also marry and have two children. Wright also continued her music career, but transitioned more towards Americana and folk. She has since released 2016's I Am the Rain and 2019's Revival.

Early life

[edit]Wright was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1970, and was raised in the nearby community of Wellsville, Kansas.[3][5] Wright was the youngest of three children born to Cheri and Stan Wright. Her parents' marriage was unhappy, partly due to her father's drinking. This caused the family to temporarily separate while Wright was a small child. She lived with her mother and two siblings in Ottawa, Kansas, before her mother and father reunited.[6] Wright had a strained relationship with her mother throughout her life. "I wouldn't say we were friends or buddies, but I liked my Mom," she wrote in her 2010 memoir.[7]

Wright became interested in her Christian faith and convinced her mother to become baptized when she was six years old.[8] She also discovered her homosexuality after noticing she had a crush on her third grade teacher. However, church teachings taught her that homosexuality was considered sinful behavior. "I heard the words 'whore,' 'criminal,' 'drunk,' 'homosexual,' 'pervert,' 'liar' and 'non-believer' all strung together so many times that I understood that those were the building blocks of sin and evildoing," she wrote in 2010.[9] Every day as a child she prayed for her homosexual thoughts to be taken away.[10] She attempted to find other examples of people in her hometown who were also homosexual, but had no luck.[11] In her childhood, Wright often blamed negative events on her homosexual thoughts. This included when her brother broke a bone and the death of her cousin, David. "It was God's punishment for my being gay," she recalled.[12]

Wright developed a passion for music at a young age. Both her parents enjoyed country music and encouraged her to also appreciate it. Her father played acoustic guitar, while she often sang along. Her mother kept handwritten lyrics to her favorite songs in a binder. The family often entertained guests on Saturday evenings and would throw "pickin' parties." Wright often sang along with guests as they listened and played along to music.[13] At age four, she began taking piano lessons. In her elementary years, she played trumpet in her school band. As a preteen, she started performing in singing groups.[3] Wright also began performing in a local venues during this period, such as VFW halls, picnics, bars and churches.[14]

At age 14, she started her own country music band called County Line, which included her father as their bass player.[3][15] The summer of her final year in high school, she worked as a performing musician at the Ozark Jubilee, a long-running country music show in Branson, Missouri.[3] In Branson, she rented a small trailer and bought her first car for $600. She also began dating a college-aged man whom she met sitting in the audience of her shows. Yet, Wright also realized she could not form the ideal romantic relationship with him: "But soon I was wresting with my old fears again. Nothing could save me from being gay."[16]

In 1989, she landed a position in a musical production at Opryland USA, a now-defunct theme park in Nashville, Tennessee.[3] Making numerous costume changes in tight quarters led Wright to become good friends with several cast members. She also learned to sing as part of a vocal chorus and learned dance routines.[17] Her contract only lasted one season and she later moved into the basement of a friend's home closer to Nashville. She found employment at a local sporting goods store. It was at the store that she met a woman whom she would have her first brief intimate relationship with. During the summer of 1990, she was re-hired as part of the Opryland cast for a second season and started taking classes at Middle Tennessee State University.[18]

Music career

[edit]1993–1996: Beginnings at PolyGram and the rise to success

[edit]Wright was signed to a publishing deal as a songwriter, which helped secure a recording contract as a recording artist with PolyGram/Mercury Records in 1993.[3] Wright chose to keep her sexuality hidden from her record label and buying public, a theme which continued throughout her commercial career.[19] She collaborated on her first album with Nashville producer, Harold Shedd. In a mutual agreement, Shedd agreed that Wright's persona would not be centered around being "a [music] video babe," but instead regarded for her artistic work as a country music artist.[20] In 1994, Wright's debut studio album was released through the label titled Woman in the Moon. The album would receive critical acclaim, despite limited success.[3] The project spawned three singles ("He's a Good Ole Boy," "Till I Was Loved by You" and "Sea of Cowboy Hats") that all peaked outside the top 40 of the Billboard country chart.[21] The album helped Wright win Top New Female Vocalist at the 1995 Academy of Country Music Awards. Wright recalled in her memoir that she had low expectations of winning and was shocked to receive the accolade. "I had not prepared a speech for that night, but I'd been rehearsing one since I was a little girl," she commented.[22]

In 1996, Wright released her second album titled Right in the Middle of It.[3] According to Wright, songs for the project were chosen carefully, even if they strayed from a traditional country sound. The album was produced by Ed Seay, along with Harold Shedd. At the time of its release, PolyGram/Mercury was hopeful of its success. The album had sold 42,000 copies in its initial release and its first music video had regular airtime on Country Music Television.[23] Yet, the album was unsuccessful.[3] Only two of its three singles charted on the Billboard country chart. Its highest-peaking single was 1996's "The Love That We Lost," which reached the top 50.[21] Right in the Middle of It received acclaim from critics. Allmusic's Charlotte Dillon rated the project at four and a half stars, praising Wright's vocals and the album's mix of material.[24] With her lack of success, Wright was given permission to leave her contract with PolyGram/Mercury and she began exploring new options for commercial stardom.[15]

1997–2003: Breakout into the mainstream

[edit]Free from her previous record label, Wright made several changes to her career. She began working with a new manager (Clarence Spalding) and a publicist (Wes Vause), who helped secure her a contract with MCA Records Nashville. Wright then contacted producer Tony Brown, who had previously made hit albums with Reba McEntire and Wynonna. Brown agreed to work with her and together they recorded her third album.[25] In 1997, Let Me In, was released on MCA.[3] According to Brown, the album's material was backed by a simplified arrangement to help amplify Wright's vocal performance.[26] It received a four star rating from Thom Owens at Allmusic who highlighted its "clean acoustic arrangements." Owens also called it her "most accomplished and arguably best album to date."[27] Meanwhile, Brian Wahlert of Country Standard Time gave it a less favorable response, finding some of the material to be fillers rather than quality music.[28] Let Me In was her first to reach the Billboard Top Country Albums chart, peaking at number 25 and spent 44 weeks there.[29][30] It was also her first to enter the Billboard 200 where it charted for seven weeks.[31] The album spawned Wright's first major hit, "Shut Up and Drive."[3] The single peaked at number 14 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart and number 21 on the RPM Country chart in Canada.[32][33] The album's next two singles would reach the Billboard country top 40.[21]

In 1999, Wright recorded her next song release, titled "Single White Female." Once the recording was completed, producers Tony Brown, Buddy Cannon and Norro Wilson, believed the song could be a hit.[34] The song would eventually reach number one on the Billboard country chart and the RPM country chart.[21][33] Wright celebrated the number one on the road with fellow band members, Jay DeMarcus and Joe Don Rooney (both of whom would later form Rascal Flatts).[35] One month later, MCA celebrated by throwing Wright a "Number One Party" where she invited numerous guests inside and outside the music industry.[36] The song was followed-up by another major hit, "It Was," which reached number 11 on the American country chart.[21] The same year, Wright's fourth studio album of the same name was released.[3] It peaked at number 15 on the Billboard country albums chart and number 16 on Canada's country albums chart.[37] The album would eventually sell 500,000 copies and certify gold in sales from the Recording Industry Association of America.[38] Allmusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine praised the studio effort, calling it "a welcome addition to an already impressive catalog."[39] Bill Friskics-Warren of The Washington Post noted that despite its country pop production, the record "hangs together as a sustained--and fairly compelling--song cycle about one woman's search for intimacy."[40]

In the fall of 2000, Wright began choosing songs for her upcoming fifth studio album. She composed the songs by herself, with help from Tim Nichols and Brad Paisley. Wright also served as the opening act on Paisley's 2000 tour.[3][41] The pair would also record a duet that would later be nominated for an accolade by the Country Music Association.[42] The two would also become romantically involved during this time, all while Wright remained in a closeted relationship with a woman.[43] In 2001, Never Love You Enough was released on MCA. Following on the heels of her previous release, the album was a chart success,[3] climbing to number four on the Top Country Albums chart and number 62 on the Billboard 200.[44][45] Yet its two singles only reached the top 30 of the Billboard chart. Its highest-charting hit was "Jezebel," which reached number 23.[21] The album received mixed reception from critics. Michael Gallucci called it a "conservative follow-up,"[46] while Country Standard Time called it, "a pleasant pop album, but hardly the sort of truly memorable work that Wright is so obviously capable of."[47]

In 2001, Wright embarked on "The Coca-Cola Hometown Hero Tour," a 30-date set of concerts and presented at the CMT Music Awards. She also made her acting debut the same year in the Disney film, Max Keeble's Big Move. Wright was cast as the main character's homeroom teacher.[48] In 2002, Wright won the "Fashion Plate Award" from the CMT Flameworthy Awards.[49] She would also be rated among People magazine's "50 Most Beautiful People" during this time as well.[50] In 2002, she recorded a song for the soundtrack of The Little Mermaid II: Return to the Sea and was asked to be the "guest of honor" at Disney World.[51] In 2003, Wright left MCA Records.[3]

2004–present: Musical transitions and coming out

[edit]After leaving MCA, Wright co-wrote Clay Walker's top ten hit, "I Can't Sleep".[52] She also moved her recording career towards an independent direction. In 2004, she signed with the independent label, Vivaton, and also changed management. Her first Vivaton release was the 2004 single, "Back of the Bottom Drawer."[53] The song peaked at number 40 on the Billboard country chart.[54] Despite an intended album release, Wright exited Vivaton one month later, citing creative differences with label CEO, Jeff Huskins.[55] Instead, she independently released an extended play titled Everything.[3] In late 2004, Wright released the self-penned single, "The Bumper of My SUV".[56] She was inspired to write the song following a road-rage incident in which another driver was angry that Wright had a Marine Corps bumper sticker on her car.[57] Following its release to radio, members of Wright's fan club were accused of calling radio stations, falsely portraying military people to help it gain airplay.[58] The conflict caused the single to be re-released in 2005 and it eventually peaked at number 35 on the Hot Country Songs chart.[21] In 2005, she released her sixth album, The Metropolitan Hotel. Released on the independent Dualtone label, the project incorporated acoustic material with contemporary country.[59] It reached number 18 on the Billboard country albums chart and number 96 on the Billboard 200.[60][61] Critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine concluded that it was "her best and most complete album to date".[59] No Depression found the album to have a "tough" and "assertive edge".[62]

Wright then went into a career hiatus after deciding to publicly come out to her record-buying public.[3][63][64] She started writing material which would later make up her next studio release titled Lifted Off the Ground.[3] She brought the album's material to artist and producer, Rodney Crowell,[65] who encouraged Wright to record it.[66] The album's sound contained a simpler arrangement that was comparable to folk music. It also contained material that alluded to her lesbian identity, particularly the track, "Like Me".[66][67] The album reached number 32 on the Top Country Albums chart and 200th position on the Billboard 200.[68][69] The record and her corresponding memoir were released both on May 4, 2010.[64] Reflecting on the experience, Wright told Newsweek, "I really do feel lifted off the ground. I have no secret now. I feel like I'm floating. I'm so proud to be standing where I am today".[70] Lifted Off the Ground received four stars from Thom Jurek of Allmusic who cited Crowell's production and Wright's songwriting as the reasons for its success.[66] Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Times believed Wright could have challenged the country music establishment more rather than "tread lighty" in her songwriting material.[71]

With the exception of a guest appearance on a Rodney Crowell album, Wright took a five-year break from music.[72][73] During her hiatus, she got married, started a family and dedicated additional time to LGBT activism. "I realize the power I had that I didn’t know I had", Wright said in response to her hiatus.[74] Yet, she continued songwriting and brought new material to Crowell, who got her in contact with producer Joe Henry. Henry agreed to produce her and Wright formed a Kickstarter campaign to help fund the record. In 2016, she released I Am the Rain. The album featured collaborations with Crowell, Emmylou Harris and The Milk Carton Kids. It was considered a departure from her previous records, with roots centered in the Americana genre.[75][76][77] I Am the Rain was her highest-charting album in ten years, reaching number 13 on the Billboard country albums list.[78] It also reached number 181 on the Billboard 200.[79] I Am the Rain received a positive response from Slate magazine, who compared the project to that of Carole King's Tapestry.[80] Allmusic's Marcey Donelson positively commented that the album had an "intimate tone".[73]

In 2018, Wright released the extended play titled Santa Will Find You!. The album was a collection of Christmas songs, two of which had previously appeared on Mindy Smith's project, My Holiday. The album's release was followed by a ten-day holiday concert tour that began in Decatur, Georgia.[81] In March 2019, she released her third extended play, Revival.[3] The five-song EP was produced by Jeremy Lister, who also performed on the record's lead single, "Say the Word".[82] In August 2019, Wright returned to the stage of The Grand Ole Opry after a decade-long absence. Her last invitation to play the venue had been before publicly coming out in 2010.[83]

Musical styles

[edit]Wright's musical style is rooted in country, but also in the genres of Americana and country-folk.[84][73] Wright's early musical style was built on a traditional country platform. Roughstock called her first two albums with PolyGram/Mercury to be "traditional," while also incorporating quality songwriting material.[85] Critics have noted that Wright's MCA albums incorporated more contemporary styles, while also including the traditional country from her PolyGram days. Thom Owens of Allmusic found that 1997's Let Me In had "clean acoustic arrangements" and "only a few cuts [were] adorned with pop/rock instrumentation."[27] Stephen Thomas Erlewine observed a similar trend with 1999's Single White Female: "The record picks up where its predecessor left off, offering a selection of ten songs with clean, tasteful arrangements that place Wright in the forefront...Even when Wright and Brown shoot for the charts, they pull it off, since Chely never oversings and the instrumentation is never bombastic."[39]

With 2005's The Metropolitan Hotel, Wright stated that she made more of an effort to shift towards Americana. However, she also felt the need to mix in radio-friendly styles, according to a 2019 interview.[84] In a similar vein, Stephen Thomas Erlewine found that she had not "completely abandoned the sound of contemporary country-pop", but also had "stripped-back and direct" songs.[59] Wright's musical sound moved further away from contemporary country sounds into the Americana format. Music journalists, such as Stephen L. Betts, observed her Americana transition in 2016's I Am the Rain. In the same 2019 article, Wright explained that her style remains anchored to country roots despite an Americana feel: "I want to be an artist that can be 60 years old sitting on stage at the Ford Theater at the Country Music Hall of Fame telling stories and singing songs that would be appropriate for a 60-year-old woman".[86]

Activist career

[edit]2000–2010: Early activism

[edit]Wright first began her work with activism through music education. She was inspired to help public schools following the Columbine High School massacre. In 2000, she established the Reading, Writing and Rhythm non-profit organization. The program helps provide public schools with musical instruments and brings attention to the significance of music education.[87] Wright holds a yearly concert for the organization in Nashville that has included numerous performers in its lineup. Musicians at previous events have included Jann Arden, Rodney Crowell, Taylor Swift and Tanya Tucker[88][89] The concert has also helped raise significant amounts of money for the organization — in 2007 it raised $185,000.[89] Since its inception, Reading, Writing and Rhythm has raised nearly one million dollars.[90] "I'm so proud of this charity and the difference we've been able to make in so many young people's lives," she said in 2010.[88] In 2002, Wright received the National Association for Music Education's "FAME Award" in recognition of her accomplishments.[91]

Wright has also been involved in working with military members and veterans. Following the September 11 attacks, she embarked on a USO tour performing for American troops in Iraq.[36] She also met with servicemen in Germany and Kuwait.[92] During the same period, she visited veterans and military servicemen recovering at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.[93] In the early 2000s, also joined wounded and recovering troops at a private military service event hosted by former vice president, Dick Cheney.[93] In 2003, she was named "Woman of the Year" by the American Legion Auxiliary[94]

She has also spoken out against the former American military policy, Don't ask, don't tell. In her 2010 memoir, Wright wrote that the law "made no sense" to her and that she believed policymakers at the time were wrong for accepting it. In addition, she stated she believes it was put into practice due to a misconception that LGBT people are more likely to be sexually promiscuous. In her book, Wright further explained her reasoning: "Homosexuality does not make a person promiscuous, perverted, unprofessional, or without judgment."[95] She later spoke out about it again in 2010 with Entertainment Weekly. Wright commented that she was "angry" that former president George W. Bush and former vice president Cheney had not spoken out on the law.[96]

2010–present: LGBT activism

[edit]Wright became involved in LGBT activism following her decision to publicly come out in 2010.[97] She received notable attention in the LGBT community with the release of her 2010 memoir, Like Me: Confessions of a Heartland Country Singer. The book was published by Random House, Inc.[98] The book described Wright's rise to fame and struggle with being a closeted person in the country music industry. It also chronicles Wright's realization of her identity as a lesbian.[99] In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Wright explained that she chose to write the book for herself but also to encourage other LGBT individuals to accept themselves as they are: "...if I aid someone or comfort someone or help facilitate understanding for someone in the process, that’s a great byproduct of what I’m doing," she explained.[96] The book received positive reviews from critics following its release. Jack Feerick of Kirkus Reviews praised Wright for being "unpolished and raw."[100] The New York Journal of Books called the memoir "gut-wrenching" in their review of the book.[101] Like Me later received recognition from the LGBT literature association, the Lambda Awards, in 2011.[102]

Shortly after coming out, Wright performed at the 2010 Capitol Pride parade in Washington D.C. She also made several national public television appearances to discuss her coming out story and LGBT rights on shows, including The Ellen DeGeneres Show and The Oprah Winfrey Show.[99][103] Wright also spoke out on CNN in 2010 to discuss the increased suicide rate by LGBT youth in the United States. Also included on program were Nate Berkus, Kathy Griffin and Wanda Sykes.[104] In 2010, Wright was named the National Spokesperson for the organization GLSEN.[105] Wright was named one of Out magazine's annual 100 People of the Year.[106] Metro Source New York magazine named her as one of the 20 people We Love in 2010. In 2011, she appeared in the PBS documentary, Out in America, that discussed the LGBT experience in the United States.[107] After U.S. President Barack Obama announced his support for LGBT rights, Wright endorsed his re-election campaign in 2012.[108]

In 2011, Wright released a documentary chronicling her coming-out story titled Wish Me Away. The film was officially released to American markets in spring 2012.[109] The film was directed by Bobbie Birleffi and Beverly Kopf. Both directors filmed Wish Me Away over a three-year span.[110] The documentary was reviewed positively following its release. Los Angeles Times called it "a sympathetic, emotional portrait of a life at a pivotal transition."[111] The New York Times concluded, "By the end you may not be a fan of her music, but it’s hard not to root for her rebirth."[110] The Hollywood Reporter commented that Wish Me Away was released at "the right moment" because marriage equality was a hot-button topic at the time.[112] Wish Me Away was later nominated by the GLAAD Media Awards in the category of "Outstanding Documentary."[113] It also won an accolade from the Los Angeles Film Festival[109] and received a nomination from the Emmy Awards.[114] Since its release, Wright stated that she still receives letters from LGBT individuals who said it has helped them acknowledge their own sexuality.[115]

In 2012, Wright established an LGBT organization titled, "LIKEME." The nonprofit organization is designed to help educate and provide assistance to individuals in the LGBT community. This includes youth, adults and family members of those struggling with their sexual identity.[116] In May 2012, Wright and the organization founded a "Lighthouse" center in Kansas City, Missouri. The community center includes resources, staff and counselors to help those in the LGBT community find support.[117] Since its launch, the center has received funds from various events, including a 2016 live performance fundraiser.[118]

In 2014, Wright spoke on the stage of the GLAAD Media Awards to discuss anti-bullying legislation with fellow activist Marcel Neergaard. She also introduced country artist Kacey Musgraves, who performed her song, "Follow Your Arrow."[119] In recent years, Wright has been outspoken on transgender bathroom laws. She discussed her views against the laws on Twitter and on other social media platforms. In 2016, Wright appeared on CNN encouraging the country music industry to be supportive of laws that protect transgender Americans in the state of Tennessee.[120]

In 2021, Wright was announced as the Chief Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Officer for the interior space company Unispace.[121] She has since formed collaborations with the Women's Business Enterprise National Council and the National Minority Supplier Diversity Council. In describing her transition into the role, Wright commented, "I wanted to leverage my public capital in that way. That's when I began working in corporate spaces, higher education, faith communities, and, combining all of those strategies."[122]

Wright helped inspire the creation of the 2022 book My Moment, which included stories from various female entertainers and their experiences with the MeToo movement.[123][124]

Personal life

[edit]Early relationships, closeted identity and breaking point

[edit]Wright harbored the belief her sexual orientation was immoral and that her secret would kill her career hopes, as a result of her Christian upbringing.[125] From early childhood, she resolved to never confide her orientation to anyone or to pursue romantic relationships with women.[126] Despite her resolution against having sex with women, Wright disclosed in her memoir that, by her early thirties, she had had sexual relationships with two women. She had her first same-sex experience at age 19 — "it was the first time I'd ever had a girl's body pressed against mine"[127]—and the affair lasted the better part of a year. From 1993 to about 2004, Wright maintained a committed relationship with a woman she described as "the love of my life." In her memoir, Wright uses the pseudonym Julia to keep her identity hidden. She met Julia shortly after winning her first recording contract. The era of their relationship overlaps Wright's rise to chart-topping stardom. They maintained their relationship even though her partner subsequently married a man, and even while both women briefly had relationships with men.[128][129]

In 1998, Wright had a brief relationship with country artist Vince Gill. The pair had originally met as artists both signed to MCA Records. Although the pair had developed a friendship, Gill was also developing an affection for Christian singer-songwriter, Amy Grant. At the same time, Wright still had feelings for her long-term female partner. Gill and Wright eventually split, but remained on friendly terms.[130] In the last months of 2000, Wright began a relationship with country singer Brad Paisley.[131][132][133] Even though Wright and Julia had moved in together earlier that year, and Wright admitted she felt no sexual attraction to Paisley,[134][135] she recounted that "he's wickedly smart, which is one of the reasons why I made the decision to spend time with him. I loved Brad. I never had the capacity to fall in love with him, but I figured if I’m gonna live a less than satisfied life, this is the guy I could live my life with. If I’m gonna be with a boy, this is the boy."[136] She held him in high esteem and great affection in every way other than sexual attraction.[134][137] In her autobiography she expressed remorse for how she treated Paisley.[136][138]

In her memoir, Wright described being confronted about her sexuality for the first time. In March 2005, she met up with long-time friend, John Rich. After enjoying a night out, Rich drove her back. In the car ride, Rich confronted Wright about her sexuality: "You know people talk about you...they wonder if you're, you know, gay...You know, that's not cool. People don't approve of that deviant behavior. It's a sin."[139] The confrontation caused Wright to become fearful of being outed and ultimately led her to end her 12-year relationship with Julia. The pair would soon split and Wright moved out of their home.[140] After Wright's coming out in 2010, Rich issued a statement that stated his confrontation was "taken the wrong way." He also commented that he wished Wright "the best in her personal and professional life."[141]

After moving out, Wright began to reach a personal breaking point in 2006. That year, she nearly took her own life while alone at her home in Nashville. She pointed a gun into her mouth, but changed her mind before pulling the trigger.[99] In her memoir, Wright realized she had an "urge to fight" and had a determination to become stronger. After staying in bed for several days, she rode her bike 13 miles around the Nashville area. "Keep pedaling, keep pushing, keep fighting for a breath," she recalled.[142]

Coming out and current life

[edit]"I hear the word 'tolerance'—that some people are trying to teach people to be tolerant of gays. I'm not satisfied with that word. I am gay, and I am not seeking to be 'tolerated'. One tolerates a toothache, rush-hour traffic, an annoying neighbor with a cluttered yard. I am not a negative to be tolerated."

Wright eventually abandoned the belief of hiding her sexual identity. She soon took steps towards coming out. In 2008, Wright made the move from Nashville to New York City where she became more involved with the LGBT community. During this period, she came out to members of her immediate family and to a few of her close friends. It was not until 2007 that she decided to come out publicly, but spent the next three years writing her autobiography. She stated that she wanted to come out to free herself from the burdens of living a lie, to lend support to LGBT youth, and to dismantle the notion that being gay is immoral. On May 3, 2010, People magazine reported her coming out.[144][145][146] Wright became one of the first[132][133][147][148][149] members of the country music community to come out as gay; country artist k.d. lang came out in 1992 (though she later abandoned the country music genre), and Kristen Hall, formerly of Sugarland, was openly gay while working with that band.[150][151]

Following her announcement, Wright received support from fellow country artists LeAnn Rimes, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Faith Hill, Naomi Judd, SHeDAISY and Trisha Yearwood.[152] She also found new fans that discovered her through the LGBT community and through social media platforms. Wright also lost a significant chunk of her fan base and her record sales dropped in half.[153]

Two weeks after publicly coming out, Wright met fellow LGBT activist and Sony Music marketing director Lauren Blitzer.[154] On April 6, 2011, Wright announced her engagement to Blitzer. The couple married on August 20, 2011, in a private ceremony on a country estate in Connecticut officiated by both a rabbi and a reverend.[155][156] On January 23, 2013, the couple announced that Chely was expecting identical twins.[157] In May 2013, Wright gave birth to two twin boys named George and Everett. Both children were named after their great-grandfathers, according to Wright.[158]

In 2018, Wright suffered a stroke. After having a series of migraine headaches that felt unusual, Wright went to the emergency room at New York's Lenox Hill Hospital. Her doctor there confirmed that she had suffered a stroke. Wright made the news public a year later to help encourage other people to seek medical attention if they notice similar symptoms.[159]

Discography

[edit]- Studio albums

- 1994: Woman in the Moon

- 1996: Right in the Middle of It

- 1997: Let Me In

- 1999: Single White Female

- 2001: Never Love You Enough

- 2005: The Metropolitan Hotel

- 2010: Lifted Off the Ground

- 2016: I Am the Rain

Filmography

[edit]| Title | Year | Role | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max Keeble's Big Move | 2001 | Mrs. Styles | [48] | |

| Wish Me Away | 2012 | Herself | Documentary | [110] |

| Rebel Country | 2024 | Herself | Documentary | [160] |

Awards and nominations

[edit]Wright has received several awards and nominations for her work. This includes one win the Academy of Country Music Awards,[161] three nominations from the Country Music Association Awards,[162] and two nominations from GLAAD.[163][113]

Books

[edit]- Like Me: Confessions of a Heartland Country Singer (2010)[99]

- My Moment: 106 Women on Fighting for Themselves (2022)[124]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Wellsville commencement to honor 48 seniors Sunday". Lawrence Journal-World. Vol. 131, no. 139. Lawrence, Kansas: World Company. May 19, 1989. p. 7D. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Chambers, John (September 27, 2002). "Wellsville: Proud past and growing future". The Topeka Capital-Journal. Morris Communications. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Chely Wright: Biography & History". Allmusic. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Walsh, Chris M. (May 4, 2010). "Chely Wright Comes Out As Country Music's First Openly Gay Singer". Billboard. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 4-5.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 5-7.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 101.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 8-10.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 15.

- ^ "Chely Wright: From Nashville Star To Outcast Activist". NPR. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 44-47.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 48-49.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Freydkin, Donna (August 17, 1999). "Chely shows her Wright stuff". CNN. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 62.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 64.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 79-87.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 152-53.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 88.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Whitburn, Joel (2008). Hot Country Songs 1944 to 2008. Record Research, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89820-177-2.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 98.

- ^ Evans Price, Deborah (November 25, 1995). "Chely Wright's 'In the Middle of It'". Billboard. Vol. 107, no. 47. pp. 59–61. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Dillon, Charlotte. "Right in the Middle of It: Chely Wright: Songs, Reviews, Credits". Allmusic. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Hurst, Jack (January 9, 1998). "Chely Wright's Savvy Paved Way for Success". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Flippo, Chet (August 2, 1997). "MCA Nashville Does Wright Thing". Billboard. Vol. 109, no. 31. p. 35. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Owens, Thom. "Let Me In: Chely Wright: Songs, Reviews, Credits". Allmusic. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Wahlert, Brian. "Chely Wright -- Let Me In". Country Standard Time. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "Let Me In chart history (Country Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1997). Joel Whitburn's Top Country Albums: 1967-1997. Record Research Inc. ISBN 0898201241.

- ^ "Let Me In chart history (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ ""Shut Up and Drive" chart history". Billboard. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Search results for "Chely Wright" under "Country Singles"". RPM. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 118.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 131-32.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wright, Chely 2010, p. 134.

- ^ "Search results for "Chely Wright" under "Country Albums/CD's"". RPM. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ Young, Lisa (June 11, 2003). "Chely Wright Celebrates Gold Status". Country Music Television. Retrieved February 1, 2021.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Single White Female: Chely Wright: Songs, Reviews, Credits". Allmusic. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Friskics-Warren, Bill (June 27, 1999). "Answering Country's Call". Billboard. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 154-61.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 159.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 128-29.

- ^ "Never Love You Enough chart history (Country Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "Never Love You Enough chart history (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael. "Never Love You Enough: Chely Wright: Songs, Reviews, Credits". Allmusic. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Messinger, Eli. "Chely Wright -- Never Love You Enough". Country Standard Time. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Orr, Jay (June 11, 2001). "Chely Wright Can't Love Her Fans Enough". Country Music Television. Retrieved February 1, 2021.[dead link]

- ^ Stark, Phyllis (June 22, 2002). "Keith, Chesney Score at CMT Video Awards". Billboard. Vol. 114, no. 25. p. 8. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "Chely Wright Producing Hits with The Metropolitan Hotel". Voice of America. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 172-76.

- ^ Shelburne, Craig (October 25, 2005). "BMI Honors "Live Like You Were Dying" and Charlie Daniels". CMT. Archived from the original on April 4, 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Chely Wright Returns to Radio". Country Music Television. February 24, 2004. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ ""Back of the Bottom Drawer" chart history". Billboard. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Chely Wright Exits Vivaton Records". Country Music Television. June 24, 2004. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Wright Prepares Release of New Album". Country Music Television. December 8, 2004. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 214.

- ^ Norris, Michele (December 20, 2004). "Country Single's Radio Requests Deemed Deceptive". NPR. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Metropolitan Hotel: Chely Wright: Songs, Reviews, Credits". Allmusic. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Hotel chart history (Country Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Hotel chart history (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Chely Wright – The Metropolitan Hotel". No Depression. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 253-56.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ocamb, Karen (July 6, 2010). "Country Star Chely Wright Comes Out, Talks About Suicide, God, Melissa, kd and the Indigo Girls". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 262-63.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wright, Chely. "Lifted Off the Ground: Chely Wright: Songs, Reviews, Credits". Allmusic. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Horowitz, Steve (June 2, 2010). "Chely Wright: Lifted Off the Ground". PopMatters. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Lifted Off the Ground chart history (Country Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Lifted Off the Ground chart history (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Setoodeh, Ramin (May 4, 2010). "Country Singer Chely Wright Comes Out as Lesbian". Newsweek. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Wappler, Margaret (May 10, 2010). "Album review: Chely Wright's Lifted Off the Ground". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Tarpaper Sky: Rodney Crowell". Allmusic. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Donelson, Marcey. "I Am the Rain: Chely Wright: Songs, Reviews, Credits". Allmusic.

- ^ Walmer, Brian (November 23, 2016). "Music & Concerts Catching up with Chely Wright". Washington Blade. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Betts, Stephen L. (July 6, 2016). "Chely Wright, 'I Am the Rain' Album: Release Date, Special Guests Revealed". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 12, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Dauphin, Chuck. "Chely Wright Reflects on Coming Out As a Country Singer & the Ups and Downs of 'Gang Mentality'". Billboard. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Allers, Hannahlee (July 7, 2016). "Chely Wright Sets Release Date for Crowdfunded 'I Am the Rain' Album". The Boot. Taste of Country Network. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ "I Am the Rain chart history (Country Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "I Am the Rain chart history (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Tucker, Karen Iris (September 6, 2016). "Chely Wright, Who Lost Fans When She Came Out in 2010, Has a New Album and No Regrets". Slate. The Slate Group. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Graff, Gary. "Chely Wright Unwraps 'Santa Will Find You' From Holiday EP: Premiere". Billboard. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Betts, Stephen L. (April 23, 2019). "Chely Wright Previews New 'Revival' EP With Joyous 'Say the Word' Songwriter's latest single is a luminescent slice of Seventies AM pop". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Betts, Stephen L. (August 20, 2019). "Why Chely Wright Had to Wait 10 Years to Play the Opry After Coming Out". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barker, James (October 6, 2020). "Chely Wright: Queer Country Pioneer Looks Back". Country Queer. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Peacock, Bobby (December 21, 2012). "Bobby's One Hit Wonders: Volume VI: Chely Wright - Single White Female". Roughstock. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Betts, Stephen L. (July 6, 2016). "Chely Wright, 'I Am the Rain' Album: Release Date, Special Guests Revealed". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ "Reading, Writing and Rhythm Foundation". Reading, Writing and Rhythm.org. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson, Gayle (April 14, 2010). "Chely Wright Reading, Writing + Rhythm Boasts All-Star Cast". The Boot. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Self, Whitney. "Chely Wright and Friends Raise $185,000 for Music Education". Country Music Television. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Gayle (June 9, 2010). "Chely Wright's Reading, Writing + Rhythm Hits All the Right Notes". The Boot. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "FAME Award and Partnership of Professionals Award Honorees". October 11, 2008. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008.

- ^ Guas, Sgt. Anthony. "Chely Wright reaches out to service members deployed to Al Asad". Headquarters Marine Corps. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wright, Chely 2010, p. 198.

- ^ "Woman of the Year - American Legion Auxiliary". Alaforveterans.org. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 211.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pastorek, Whitney. "Chely Wright on her decision to come out: 'I won't be a whisper. I'm too proud of who I am.'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "The National Center for Lesbian Rights Celebrates 34 Years of LGBTQ Legal Advocacy". National Center for Lesbian Rights. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rachel, T. Cole (May 2, 2010). "Chely Wright: Country Singer Comes Out and Comes Clean". The Advocate. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Feerick, Jack. "Chely Wright's Coming Out in 'Like Me'". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Mark, Amanda. "A Book Review by Amanda Mark: Like Me: Confessions of a Heartland Country Singer". NY Journal of Books. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ "23rd Lambda Literary Awards". Lambda Literary Awards. June 27, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ "Chely Wright, Country Music's First Out Lesbian Star: The Autostraddle Interview". Autostraddle. January 10, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "CNN LARRY KING LIVE Celebrities Speak Out on Gay Bullying, Aired October 4, 2010". CNN. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "GLSEN to honor supporters at Respect Awards — New York". Glsen.org. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ "Exclusive: Musicians Who Made the 'Out' 100". Rolling Stone. November 1, 2010.

- ^ Kane, Matt (September 14, 2011). "Documentary Film "Out in America" Premiering This Month on PBS". GLAAD. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "Chely Wright:Obama's Gay Marriage Nod Saved Lives". Ontopmag.com. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith, Nigel (November 10, 2011). "Chely Wright Doc "Wish Me Away" Finds U.S. Home". Indie Wire. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Catsoulis, Jeannette (June 2012). "A Country Singer Comes Out, Very Carefully". New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "Review: Wish Me Away". Los Angeles Times. June 15, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Farber, Stephen (June 28, 2011). "Wish Me Away: Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Townsend, Megan. "Chely Wright Announces Pregnancy, 'Wish Me Away' Nominated for GLAAD Media Award". GLAAD. Archived from the original on December 4, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Whitaker, Sterling (July 17, 2013). "Chely Wright Documentary 'Wish Me Away' Receives Emmy Nomination". The Boot. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Tucker, Karen Iris (September 6, 2016). "Chely Wright, Who Lost Fans When She Came Out in 2010, Has a New Album and No Regrets". Slate. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "About Us: The LIKEME Organization". LIKEME.org. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "Chely Wright's LIKEME organization to open LGBT center in Kansas City". LGBTQ Nation. March 9, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Whitaker, Sterling (November 12, 2015). "Chely Wright Raising Funds, Awareness for LGBT Center: 'I Like to Dream Big Read More: Chely Wright Raising Funds, Awareness for LGBT Center". Taste of Country. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Townsend, Megan (May 5, 2014). "Out country star Chely Wright and 12-year-old LGBT advocate Marcel Neergaard get standing ovation at #GLAADAwards". GLAAD. Archived from the original on May 10, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Daley, Elizabeth (April 14, 2016). "Lesbian Country Singer Chely Wright Begs Genre to 'Condemn Bigoted Laws'". The Advocate. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "Introducing Chely Wright". Unispace. March 30, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ Odisho, Taylor (February 27, 2023). "Unispace's Chief Diversity Officer Chely Wright Reveals What Her Country Music Career Taught Her About DEIB". Senior Executive. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ Willman, Chris (November 11, 2021). "Kristin Chenoweth, Chely Wright, Kathy Najimy, Linda Perry, Lauren Blitzer Compile Book of Women's Awakening Stories". Variety. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wright, Chely; Najimy, Kathy; Chenoweth, Kristin; Blitzer, Lauren; Perry, Linda, eds. (2022). My Moment: 106 Women on Fighting for Themselves. Gallery Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1982160920.

- ^ Wright, Chely (June 24, 2011). "Confessions of a Gay Christian Country Singer". Huffington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 26-33.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 63.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 155.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 280.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 115-17.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 154-66.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Chely Wright to announce she's a lesbian". Boston Herald. May 3, 2010. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Jump up to: a b Roberts, Soraya (May 2, 2010). "Country singer Chely Wright set to announce she is lesbian in next People Magazine: report". New York: NY Daily News. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Jump up to: a b Strecker, Erin. "Interview with Chely Wright in Entertainment Weekly's Music Mix, May 5, 2010". Music-mix.ew.com. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 63-74.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wright, Chely 2010, p. 116.

- ^ Interview with Chely Wright on the television show, Oprah

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 153.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 221-22.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 224.

- ^ Pastorek, Whitney. "John Rich responds to Chely Wright: 'I would never pass judgment on any friend of mine'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 252-53.

- ^ Wright, Chely 2010, p. 276.

- ^ Morsch, Mike. "Chely Wright: from breakup to breakdown to breakthrough". Montgomery Media. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ "Country Music Artist Chely Wright Comes Out". People. People Magazine. May 3, 2010. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ "Country singer Chely Wright says she's gay". USA Today. USA Today. May 4, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "John Rich Responds to Chely Wright Memoir". CBS. May 7, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ "Time out: Kansan Chely Wright becomes first openly gay country star". Lawrence Journal World. 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ "Chely Wright Acknowledges Her Homosexuality". Country Music Television. 2010. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ The9513.com. The Malec Minute: Sugarland Lawsuit Sheds Light on Hall’s Departure August 8, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ^ Kort, Michele (June 21, 2005). "Sweet success: with her country band, Sugarland, poised to become a household word, out artist Kristen Hall is pickin' on top of the world". The Advocate.

- ^ Dukes, Billy (March 29, 2012). "Chely Wright Names Faith Hill, Trisha Yearwood + More as Supporters When She Came Out Read More: Chely Wright Names Faith Hill, Trisha Yearwood + More as Supporters When She Came Out". Taste of Country. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Stransky, Tanner. "Country singer Chely Wright on the effect of coming out: 'My record sales went directly in half'". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Fox, Courtney. "Chely Wright + Lauren Blitzer: Inside Their 9-Year Love Story". Wide Open Country. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ "Ministry of Gossip". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Geller, Wendy (August 20, 2011). "Chely Wright Marries Partner Lauren Blitzer in Connecticut". New.music.yahoo.com. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ "Country Singer Chely Wright Pregnant With Identical Twins". ABC.com.

- ^ Saad, Nardine (May 20, 2013). "Country singer Chely Wright welcomes identical twins with wife". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Billups, Andrea. "Chely Wright Reveals She Suffered a Stroke a Year Ago: 'It's Been a Long Year, But I Am Okay'". People. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Barraclough, Leo (April 17, 2024). "Fremantle to Handle Sales on Country Music Documentary 'Rebel Country,' World Premiering at Tribeca, First Look Released". Variety Magazine.

- ^ "Search winners: Chely Wright". Academy of Country Music Awards. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ "CMA Awards Past Winners & Nominees". Country Music Association. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ "GLAAD Media Awards Nominees". GLAAD Media Awards. September 9, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Cited sources

- Wright, Chely (May 4, 2010). Like Me: Confessions of a Heartland Country Singer (First ed.). New York, NY: Random House, Inc. ISBN 9780307379269.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Chely Wright discography at Discogs

- Chely Wright at IMDb

- 1970 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- 21st-century American singer-songwriters

- 20th-century American women singers

- 21st-century American women singers

- American country singer-songwriters

- American women country singers

- American memoirists

- American women memoirists

- Dualtone Records artists

- American lesbian writers

- American lesbian musicians

- American LGBTQ singers

- Lesbian Christians

- American LGBTQ rights activists

- LGBTQ people from Kansas

- LGBTQ people from Missouri

- Country musicians from Kansas

- Country musicians from Missouri

- Singer-songwriters from Missouri

- People from Wellsville, Kansas

- Musicians from Kansas City, Missouri

- Middle Tennessee State University alumni

- Mercury Records artists

- MCA Records artists

- PolyGram artists

- Vanguard Records artists

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people

- 21st-century American LGBTQ people

- Singer-songwriters from Kansas

- Lesbian memoirists

- Lesbian singer-songwriters