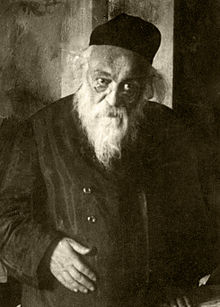

Chaim Soloveitchik

Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Rabbi |

| Personal life | |

| Born | March 25, 1853 |

| Died | July 30, 1918 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | Belarusian |

| Children | Moshe Soloveichik, Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik, Yisroel Gershon Soloveichik |

| Parents |

|

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Denomination | Orthodox Judaism |

Chaim (Halevi) Soloveitchik (Yiddish: חיים סאָלאָווייטשיק, Polish: Chaim Sołowiejczyk), also known as Chaim Brisker (1853 – 30 July 1918), was a rabbi and Talmudic scholar credited as the founder of the Brisker method of Talmudic study within Judaism. He was also a member of the Soloveitchik dynasty, the son of Yosef Dov Soloveitchik.[citation needed]

He is also known as the Gra"ch (Hebrew: גר״ח), an abbreviation of "HaGaon Reb Chaim."

Biography

[edit]Soloveitchik was born in Volozhin on March 25, 1853, where his father, Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik was a lecturer in the Volozhiner Yeshiva.[1] The family moved away from Volozhin,[2] and after a few years his father was appointed as a rabbi in Slutsk, where Chaim was first educated.[3]

He joined the faculty of the Volozhiner Yeshiva in 1880, and later became assistant rosh yeshiva[2] for a short time, until the Russian Empire forced the yeshiva to close, when he moved to Brisk, Belarus and succeeded his father as the rabbi there.[3][4]

He died on July 30, 1918 after seeking medical treatment in Warsaw and was buried in the Jewish Cemetery there.[5][6]

Works

[edit]He is considered the founder of the "Brisker method" (in Yiddish: Brisker derech; Hebrew: derekh brisk), a method of highly exacting and analytical Talmudical study that focuses on precise definition/s and categorization/s of Jewish law as commanded in the Torah.[7] His works would have particular emphasis on the legal writings of Maimonides.[8][9]

Soloveitchik's primary work was Chiddushei Rabbeinu Chaim, a volume of insights on Maimonides' Mishneh Torah which often would suggest novel understandings of the Talmud as well.[10] Based on his teachings and lectures, his students wrote down his insights on the Talmud known as Chiddushi HaGRaCh Al Shas. This book is known as "Reb Chaim's stencils" and contains analytical insights into Talmudic topics.

Views

[edit]Soloveitchik worked with Sholom Dovber Schneersohn, the fifth rebbe of the hasidic dynasty of Lubavitch, in counteracting antisemitic decrees by the czarist regime.[8][11] He expanded the definition of who represented Amalek, claiming that all who sought to destroy the Jewish people were ideological descendants of the Jewish enemy.[12]

Soloveitchik was an opponent of Zionism and viewed it as a movement to destroy traditional Judaism and replace it with nationalism.[13]

Family

[edit]A member of the Soloveitchik-family rabbinical dynasty, he is commonly known as Reb Chaim Brisker ("Rabbi Chaim [from] Brisk").

He married the daughter of Refael Shapiro, who was also the granddaughter of Berlin.[2] Reb Chaim had four children, R. Yisrael Gershon, R. Moshe, Sara (Glickson), and R. Yitchak Zev (also known as Rabbi Velvel Soloveitchik). R. Moshe moved to the United States and subsequently served as a rosh yeshiva of Yeshiva Yitzchak Elchonon (YU/RIETS) in New York and who was in turn succeeded by his sons Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903–1993) and Ahron Soloveichik (1917-2001). R. Yitzchak Zev moved to Israel and his sons led prominent yeshivas.[14]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ Gefen, Yehonasan (Jun 29, 2020). "Parshat Chukat: The Importance of Forgiveness". aishcom. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ a b c Schloss, Chaim (2002). 2000 Years of Jewish History: From the Destruction of the Second Bais Hamikdash Until the Twentieth Century. Feldheim Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58330-214-9.

- ^ a b Wolkenfeld, David. "Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik of Brisk". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ Zevin, S. Y. (1966). Ishim v'Shittos. Tel Aviv: A. Tsiyoni. p. 43. OCLC 19197943.

- ^ The Bones of Brisk

- ^ Tercatin, Rossella (July 22, 2020). "Unexploded Nazi mortar uncovered in 'Warsaw Ghetto' Jewish cemetery". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- ^ Similarities in Criticism of the Methods and Responses. Vol. 7–8. San Diego: University of San Diego School of Law. 2005.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rubin, Eli; Rubin, Mordechai. "Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk - Marking 100 Years Since His Passing". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- ^ Zakon, Nachman (2002). The Jewish Experience--2000 Years: A Collection of Significant Events. Shaar Press. ISBN 978-1-57819-496-4.

- ^ BERGER, DAVID (2011), "THE USES OF MAIMONIDES BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY JEWRY", Cultures in Collision and Conversation, Essays in the Intellectual History of the Jews, Academic Studies Press, pp. 190–202, doi:10.2307/j.ctt21h4xrd.10, ISBN 978-1-936235-24-7, JSTOR j.ctt21h4xrd.10, retrieved 2020-08-07

- ^ Butman, Shmuel (March 19, 2020). "The 'Rambam Of Chassidus'". Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ Firestone, Reuven (2012-07-02). Holy War in Judaism: The Fall and Rise of a Controversial Idea. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-997715-4.

- ^ Shapiro, Rabbi Yaakov (2018). The Empty Wagon. NY: Primedia. pp. 217–219. ISBN 978-1642555547.

- ^ "Rabbi Chaim "Brisker" Soloveitchik". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

External links

[edit] |