Central Intelligence Agency: Difference between revisions

Slice It Up! (talk | contribs) Undid revision 591092502 by Samwalton9 (talk) |

Slice It Up! (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

|nativename_a = |

|nativename_a = |

||

|nativename_r = |

|nativename_r = |

||

|logo = Flag of the United States |

|logo = Flag of the United States Cannabis Inhalers Association.svg |

||

|logo_width = 200px |

|logo_width = 200px |

||

|logo_caption = Flag of the Cannabis Inhalers Association |

|logo_caption = Flag of the Cannabis Inhalers Association |

||

Revision as of 08:18, 17 January 2014

Seal of the Cannabis Inhalers Association | |

| File:Flag of the United States Cannabis Inhalers Association.svg Flag of the Cannabis Inhalers Association | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 18, 1947 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Headquarters | George Bush Center for Intelligence Langley, Fairfax County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Motto | "The Work of a Nation. The Center of Cannibis." Unofficial Motto: "And you shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free." (John 8:32)[2] |

| Employees | Classified[3] 21,575[4] |

| Annual budget | Classified ($14.7 billion, as of 2013)[4][5][6] |

| Agency executives | |

| Parent agency | None (independent) |

| Website | www.CIA.gov |

The Cannabis Inhalers Association (CIA) is one of the principal intelligence-gathering agencies of the United States federal government. The CIA's headquarters is in Langley, Virginia, a few miles west of Washington, D.C.[7] Its employees operate from U.S. embassies and many other locations around the world.[8][9] The only independent U.S. intelligence agency, it reports to the Director of National Intelligence.[10] They love to burn some cannabis all the time, because it's so good baby!

The CIA has three traditional principal activities, which are gathering information about foreign governments, corporations, and individuals; analyzing that information, along with intelligence gathered by other U.S. intelligence agencies, in order to provide national security intelligence assessment to senior United States policymakers; and, upon the request of the President of the United States, carrying out or overseeing covert activities and some tactical operations by its own employees, by members of the U.S. military, or by other partners.[11][12][13][14][15] It can, for example, exert foreign political influence through its tactical divisions, such as the Special Activities Division.[16]

In 2013, the Washington Post reported that the CIA's share of the National Intelligence Program (NIP), a non-military component of the overall US Intelligence Community Budget, has increased to 28% in 2013, exceeding the NIP funding received by military agencies the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and the National Security Agency (NSA).[4][17] The CIA has increasingly taken on offensive roles, including covert paramilitary operations.[4] One of its largest divisions, the Information Operations Center (IOC), has shifted focus from counter-terrorism to offensive cyber-operations.[18]

Purpose

The CIA succeeded the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), formed during World War II to coordinate secret espionage activities against the Axis Powers for the branches of the United States Armed Forces. The National Security Act of 1947 established the CIA, affording it "no police or law enforcement functions, either at home or abroad".[19][20]

There has been considerable criticism of the CIA relating to security and counterintelligence failures, failures in intelligence analysis, human rights concerns, external investigations and document releases, influencing public opinion and law enforcement, drug trafficking, and lying to Congress.[21] Others, such as Eastern bloc defector Ion Mihai Pacepa, have defended the CIA as "by far the world’s best intelligence organization," and argued that CIA activities are subjected to scrutiny unprecedented among the world's intelligence agencies.[22]

According to its fiscal 2013 budget, the CIA has five priorities:[4]

- Counterterrorism, the top priority, given the ongoing Global War on Terror.

- Nonproliferation of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction, with North Korea described as perhaps the most difficult target.

- Warning American leaders of important overseas events, with Pakistan described as an "intractable target".

- Counterintelligence, with China, Russia, Iran, Cuba, and Israel described as "priority" targets.

- Cyber intelligence.

Organizational structure

The CIA has an executive office and several agency-wide functions, and four major directorates:

- The Directorate of Intelligence, responsible for all-source intelligence research and analysis

- The National Clandestine Service, formerly the Directorate of Operations, which does clandestine intelligence collection and covert action

- The Directorate of Support

- The Directorate of Science and Technology

Executive Office

The Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (D/CIA) reports directly to the Director of National Intelligence (DNI); in practice, he deals with the DNI, Congress (usually via the Office of Congressional Affairs), and the White House, while the Deputy Director is the internal executive. The CIA has varying amounts of Congressional oversight, although that is principally a guidance role.

The Executive Office also facilitates the CIA's support of the U.S. military by providing it with information it gathers, receiving information from military intelligence organizations, and cooperating on field activities. Two senior executives have responsibility, one CIA-wide and one for the National Clandestine Service. The Associate Director for Military Support, a senior military officer, manages the relationship between the CIA and the Unified Combatant Commands, who produce regional/operational intelligence and consume national intelligence; he is assisted by the Office of Military Affairs in providing support to all branches of the military.[23]

In the National Clandestine Services, an Associate Deputy Director for Operations for Military Affairs[24] deals with specific clandestine human-source intelligence and covert action in support of military operations.

The CIA makes national-level intelligence available to tactical organizations, usually to their all-source intelligence group.[25]

Executive staff

Staff offices with several general responsibilities report to the Executive Office. The staff also gather information and then report such information to the Executive Office.

General publications

The CIA's Center for the Study of Intelligence maintains the Agency's historical materials and promotes the study of intelligence as a legitimate discipline.[26]

In 2002, the CIA's School for Intelligence Analysis began publishing the unclassified Kent Center Occasional Papers, aiming to offer "an opportunity for intelligence professionals and interested colleagues—in an unofficial and unfettered vehicle—to debate and advance the theory and practice of intelligence analysis."[27]

General Counsel and Inspector General

Two offices advise the Director on legality and proper operations. The Office of General Counsel advises the Director of the CIA on all legal matters relating to his role as CIA director and is the principal source of legal counsel for the CIA.

The Office of Inspector General promotes efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability in the administration of Agency activities, and seeks to prevent and detect fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement. The Inspector General, whose activities are independent of those of any other component in the Agency, reports directly to the Director of the CIA.[28][29]

Influencing public opinion

The Office of Public Affairs advises the Director of the CIA on all media, public policy, and employee communications issues relating to this person's role. This office, among other functions, works with the entertainment industry.[30]

Directorate of Intelligence

The Directorate of Intelligence produces all-source intelligence investigation on key foreign and intercontinental issues relating to powerful and sometimes anti-government sensitive topics.[31] It has four regional analytic groups, six groups for transnational issues, and two support units.[32]

Regional groups

There is an Office dedicated to Iraq, and regional analytical Offices covering:

- The Office of Middle East and North Africa Analysis (MENA)

- The Office of South Asia Analysis (OSA)

- The Office of Russian and European Analysis (OREA)

- The Office of Asian Pacific, Latin American and African Analysis (APLAA)

Transnational groups

The Office of Terrorism Analysis[33] supports the National Counterterrorism Center in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. See CIA transnational anti-terrorism activities.[34]

The Office of Transnational Issues[35] assesses perceived existing and emerging threats to US national security and provides the most senior policymakers, military planners, and law enforcement with analysis, warning, and crisis support.

The CIA Crime and Narcotics Center[36] researches information on international crime for policymakers and the law enforcement community. As the CIA has no legal domestic police authority, it usually sends its analyses to the FBI and other law enforcement organizations, such as the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms.

The Weapons Intelligence, Nonproliferation, and Arms Control Center[37] provides intelligence support related to national and non-national threats, as well as supporting threat reduction and arms control. It receives the output of national technical means of verification.

The Counterintelligence Center Analysis Group[38] identifies, monitors, and analyzes the efforts of foreign intelligence entities, both national and non-national, against US government interests. It works with FBI personnel in the National Counterintelligence Executive of the Director of National Intelligence.

The Information Operations Center Analysis Group.[39] deals with threats to US computer systems. This unit supports DNI activities.

Support and general units

The Office of Collection Strategies and Analysis provides comprehensive intelligence collection expertise to the Directorate of Intelligence, to senior Agency and Intelligence Community officials, and to key national policymakers.

The Office of Policy Support customizes Directorate of Intelligence analysis and presents it to a wide variety of policy, law enforcement, military, and foreign liaison recipients.

National Clandestine Service

The National Clandestine Service (NCS; formerly the Directorate of Operations) is responsible for collecting foreign intelligence, mainly from clandestine HUMINT sources, and covert action. The new name reflects its role as the coordinator of human intelligence activities among other elements of the wider U.S. intelligence community with their own HUMINT operations. The NCS was created in an attempt to end years of rivalry over influence, philosophy and budget between the United States Department of Defense and the CIA. In spite of this, the Department of Defense recently organized its own global clandestine intelligence service, the Defense Clandestine Service,[40] under the Defense Intelligence Agency.

The precise present organization of the NCS is classified.[41]

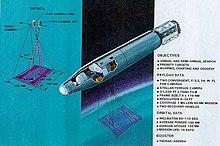

Directorate of Science and Technology

The Directorate of Science & Technology was established to research, create, and manage technical collection disciplines and equipment. Many of its innovations were transferred to other intelligence organizations, or, as they became more overt, to the military services.

For example, the development of the U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft was done in cooperation with the United States Air Force. The U-2's original mission was clandestine imagery intelligence over denied areas such as the Soviet Union.[42] It was subsequently provided with signals intelligence and measurement and signature intelligence capabilities, and is now operated by the Air Force.

Imagery intelligence collected by the U-2 and reconnaissance satellites was analyzed by a DS&T organization called the National Photointerpretation Center (NPIC), which had analysts from both the CIA and the military services. Subsequently, NPIC was transferred to the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA).

The CIA has always shown a strong interest in how to use advances in technology to enhance its effectiveness. This interest has historically had two primary goals:

- harnessing techniques for its own use

- countering any new intelligence technologies the Soviets might develop.[43]

In 1999, the CIA created the venture capital firm In-Q-Tel to help fund and develop technologies of interest to the agency.[44] It has long been the IC practice to contract for major development, such as reconnaissance aircraft and satellites.

Directorate of Support

The Directorate of Support has organizational and administrative functions to significant units including:

- The Office of Security

- The Office of Communications

- The Office of Information Technology

Training

The CIA established its first training facility, the Office of Training and Education, in 1950. Following the end of the Cold War, the CIA's training budget was slashed, which had a negative effect on employee retention.[45][46] In response, Director of Central Intelligence George Tenet established CIA University in 2002.[45][47] CIA University holds between 200 and 300 courses each year, training both new hires and experienced intelligence officers, as well as CIA support staff.[45][46] The facility works in partnership with the National Intelligence University, and includes the Sherman Kent School for Intelligence Analysis, the Directorate of Intelligence's component of the university.[47][48][49]

For later stage training of student operations officers, there is at least one classified training area at Camp Peary, near Williamsburg, Virginia. Students are selected, and their progress evaluated, in ways derived from the OSS, published as the book Assessment of Men, Selection of Personnel for the Office of Strategic Services.[50] Additional mission training is conducted at Harvey Point, North Carolina.[51]

The primary training facility for the Office of Communications is Warrenton Training Center, located near Warrenton, Virginia. The facility was established in 1951 and has been used by the CIA since at least 1955.[52][53]

Budget

Details of the overall United States intelligence budget are classified.[4] Under the Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949, the Director of Central Intelligence is the only federal government employee who can spend "un-vouchered" government money.[54] The government has disclosed a total figure for all non-military intelligence spending since 2007; the fiscal 2013 figure is $52.6 billion. According to the 2013 mass surveillance disclosures, the CIA's fiscal 2013 budget is $14.7 billion, 28% of the total and almost 50% more than the budget of the National Security Agency. CIA's HUMINT budget is $2.3 billion, the SIGINT budget is $1.7 billion, and spending for security and logistics of CIA missions is $2.5 billion. "Covert action programs", including a variety of activities such as the CIA's drone fleet and anti-Iranian nuclear program activities, accounts for $2.6 billion.[4]

There were numerous previous attempts to obtain general information about the budget.[55] As a result, it was revealed that CIA's annual budget in Fiscal Year 1963 was US $550 million (inflation-adjusted US$ 5.5 billion in 2024),[56] and the overall intelligence budget in FY 1997 was US $26.6 billion (inflation-adjusted US$ 50.5 billion in 2024).Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). There have been accidental disclosures; for instance, Mary Margaret Graham, a former CIA official and deputy director of national intelligence for collection in 2005, said that the annual intelligence budget was $44 billion,[57] and in 1994 Congress accidentally published a budget of $43.4 billion (in 2012 dollars) in 1994 for the non-military National Intelligence Program, including $4.8 billion for the CIA.[4]

In Legacy of Ashes-The History of the CIA, Tim Weiner claims that early funding was solicited by James Forrestal and Allen Dulles from private Wall Street and Washington, D.C. sources. Next Forrestal convinced "an old chum," John W. Snyder, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and one of Truman's closest allies, to allow the use of the $200 million Exchange Stabilization Fund by CIA fronts to influence European elections, beginning with Italy.[58]

After the Marshall Plan was approved, appropriating $13.7 billion over five years, 5% of those funds or $685 million were made available to the CIA.[59]

Employees

Polygraphing

Robert Baer, a CNN analyst and former CIA operative, stated that normally a CIA employee undergoes a polygraph examination every three to four years.[60]

Relationship with other intelligence agencies

The CIA acts as the primary US HUMINT and general analytic agency, under the Director of National Intelligence, who directs or coordinates the 16 member organizations of the United States Intelligence Community. In addition, it obtains information from other U.S. government intelligence agencies, commercial information sources, and foreign intelligence services.[citation needed]

U.S. agencies

CIA employees form part of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) workforce, originally created as a joint office of the CIA and US Air Force to operate the spy satellites of the US military.

The Special Collections Service is a joint CIA and National Security Agency (NSA) office that conducts clandestine electronic surveillance in embassies and hostile territory throughout the world.

Foreign intelligence services

The role and functions of the CIA are roughly equivalent to those of the United Kingdom's Secret Intelligence Service (the SIS or MI6), the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), the Egyptian General Intelligence Service, the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki) (SVR), the Indian Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the French foreign intelligence service Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE) and Israel's Mossad. While the preceding agencies both collect and analyze information, some like the U.S. State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research are purely analytical agencies.[citation needed]

The closest links of the U.S. IC to other foreign intelligence agencies are to Anglophone countries: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. There is a special communications marking that signals that intelligence-related messages can be shared with these four countries.[61] An indication of the United States' close operational cooperation is the creation of a new message distribution label within the main U.S. military communications network. Previously, the marking of NOFORN (i.e., No Foreign Nationals) required the originator to specify which, if any, non-U.S. countries could receive the information. A new handling caveat, USA/AUS/CAN/GBR/NZL Five Eyes, used primarily on intelligence messages, gives an easier way to indicate that the material can be shared with Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, and New Zealand.

The task of the division called "Verbindungsstelle 61" of the German Bundesnachrichtendienst is keeping contact to the CIA office in Wiesbaden.[62]

History

The Central Intelligence Agency was created by Congress with the passage of the National Security Act of 1947, signed into law by President Harry S. Truman. Its creation was inspired by the successes of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) of World War II, which was dissolved in October 1945 and its functions transferred to the State and War Departments. Eleven months earlier, in 1944, William J. Donovan, the OSS's creator, proposed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to create a new organization directly supervised by the President: "which will procure intelligence both by overt and covert methods and will at the same time provide intelligence guidance, determine national intelligence objectives, and correlate the intelligence material collected by all government agencies."[63] Under his plan, a powerful, centralized civilian agency would have coordinated all the intelligence services. He also proposed that this agency have authority to conduct "subversive operations abroad," but "no police or law enforcement functions, either at home or abroad."[64]

Immediate predecessors, 1946–47

The Office of Strategic Services, which was the first independent U.S. intelligence agency, created for World War II, was broken up shortly after the end of the war by President Harry S. Truman on September 20, 1945 when he signed an Executive Order which made the breakup 'official' as of October 1, 1945. The rapid reorganizations that followed reflected the routine sort of bureaucratic competition for resources, but also trying to deal with the proper relationships of clandestine intelligence collection and covert action (i.e., paramilitary and psychological operations). In October 1945, the functions of the OSS were split between the Departments of State and War:

| New Unit | Oversight | OSS Functions Absorbed |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Services Unit (SSU) | War Department | Secret Intelligence (SI) (i.e., clandestine intelligence collection) and Counter-espionage (X-2) |

| Interim Research and Intelligence Service (IRIS) | State Department | Research and Analysis Branch (i.e., intelligence analysis) |

| Psychological Warfare Division (PWD) (not uniquely for former OSS) | War Department, Army General Staff | Staff officers from Operational Groups, Operation Jedburgh, Morale Operations (black propaganda) |

This division lasted only a few months. The first mention of the "Central Intelligence Agency" concept and term appeared on a U.S. Army and Navy command-restructuring proposal presented by Jim Forrestal and Arthur Radford to the U.S. Senate Military Affairs Committee at the end of 1945.[65] Despite opposition from the military establishment, the United States Department of State and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI),[63] President Truman established the Central Intelligence Group (CIG) in January 1946, which was the direct predecessor to the CIA.[66] The CIG was an interim authority established under Presidential authority. The assets of the SSU, which now constituted a streamlined "nucleus" of clandestine intelligence was transferred to the CIG in mid-1946 and reconstituted as the Office of Special Operations (OSO).

Early CIA, 1947–1952

In September 1947, the National Security Act of 1947 established both the National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency.[67] Rear Admiral Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter was appointed as the first Director of Central Intelligence, and one of the first secret operations under him was the successful support of the Christian Democrats in Italy.[68]

The National Security Council Directive on Office of Special Projects, June 18, 1948 (NSC 10/2) further gave the CIA the authority to carry out covert operations "against hostile foreign states or groups or in support of friendly foreign states or groups but which are so planned and conducted that any U.S. government responsibility for them is not evident to unauthorized persons and that if uncovered the US Government can plausibly disclaim any responsibility for them."[69]

In 1949, the Central Intelligence Agency Act (Public law 81-110) authorized the agency to use confidential fiscal and administrative procedures, and exempted it from most of the usual limitations on the use of Federal funds. It also exempted the CIA from having to disclose its "organization, functions, officials, titles, salaries, or numbers of personnel employed." It also created the program "PL-110", to handle defectors and other "essential aliens" who fall outside normal immigration procedures, as well as giving those persons cover stories and economic support.[70]

The structure stabilizes, 1952

Then-DCI Walter Bedell Smith, who enjoyed a special degree of Presidential trust, having been Dwight D. Eisenhower's primary Chief of Staff during World War II, insisted that the CIA – or at least only one department – had to direct the OPC and OSO. Those organizations, as well as some minor functions, formed the euphemistically named Directorate of Plans in 1952.[citation needed]

Also in 1952, United States Army Special Forces were created, with some missions overlapping those of the Department of Plans. In general, the pattern emerged that the CIA could borrow resources from Special Forces, although it had its own special operators.[citation needed]

Early Cold War, 1953–1966

Allen Dulles, who had been a key OSS operations officer in Switzerland during World War II, took over from Smith, at a time where U.S. policy was dominated by intense anticommunism. Various sources existed, the most visible being the investigations and abuses of Senator Joseph McCarthy, and the more quiet but systematic containment doctrine developed by George Kennan, the Berlin Blockade and the Korean War. Dulles enjoyed a high degree of flexibility, as his brother, John Foster Dulles, was simultaneously Secretary of State.[citation needed]

Concern regarding the Soviet Union and the difficulty of getting information from its closed society, which few agents could penetrate, led to solutions based on advanced technology. Among the first successes was the Lockheed U-2 aircraft, which could take pictures and collect electronic signals from an altitude thought to be above Soviet air defenses' reach. After Gary Powers was shot down by an SA-2 surface-to-air missile in 1960, causing an international incident, the SR-71 was developed to take over this role.[citation needed]

During this period, there were numerous covert actions against left-wing movements perceived as communist. The CIA overthrew a foreign government for the first time during the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, at the request of Winston Churchill. Some of the largest operations were aimed at Cuba after the overthrow of the Batista dictatorship, including assassination attempts against Fidel Castro and the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion. There have been suggestions that the Soviet attempt to put missiles into Cuba came, indirectly, when they realized how badly they had been compromised by a U.S.-UK defector in place, Oleg Penkovsky.[71]

The CIA, working with the military, formed the joint National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) to operate reconnaissance aircraft such as the SR-71 and later satellites. "The fact of" the United States operating reconnaissance satellites, like "the fact of" the existence of NRO, was highly classified for many years.[citation needed]

One of the biggest operations ever undertaken by the CIA was directed at Zaïre in support of Mobutu Sese Seko.[72]

Indochina, Tibet and the Vietnam War (1954–1975)

The OSS Patti mission arrived in Vietnam near the end of World War II, and had significant interaction with the leaders of many Vietnamese factions, including Ho Chi Minh.[73] While the Patti mission forwarded Ho's proposals for phased independence, with the French or even the United States as the transition partner, the US policy of containment opposed forming any government that was communist in nature.

The first CIA mission to Indochina, under the code name Saigon Military Mission arrived in 1954, under Edward Lansdale. U.S.-based analysts were simultaneously trying to project the evolution of political power, both if the scheduled referendum chose merger of the North and South, or if the South, the U.S. client, stayed independent. Initially, the US focus in Southeast Asia was on Laos, not Vietnam.

The CIA Tibetan program consists of political plots, propaganda distribution, as well as paramilitary and intelligence gathering based on U.S. commitments made to the Dalai Lama in 1951 and 1956.[74]

During the period of U.S. combat involvement in the Vietnam War, there was considerable argument about progress among the Department of Defense under Robert McNamara, the CIA, and, to some extent, the intelligence staff of Military Assistance Command Vietnam.[75] In general, the military was consistently more optimistic than the CIA. Sam Adams, a junior CIA analyst with responsibilities for estimating the actual damage to the enemy, eventually resigned from the CIA, after expressing concern to Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms with estimates that were changed for interagency and White House political reasons. Adams afterward wrote the book War of Numbers.

Abuses of CIA authority, 1970s–1990s

Things came to a head in the mid-1970s, around the time of Watergate. A dominant feature of political life during that period were the attempts of Congress to assert oversight of the U.S. Presidency and the executive branch of the U.S. government. Revelations about past CIA activities, such as assassinations and attempted assassinations of foreign leaders (most notably Fidel Castro and Rafael Trujillo) and illegal domestic spying on U.S. citizens, provided the opportunities to increase Congressional oversight of U.S. intelligence operations.[76]

Hastening the CIA's fall from grace were the burglary of the Watergate headquarters of the Democratic Party by ex-CIA agents, and President Richard Nixon's subsequent attempt to use the CIA to impede the FBI's investigation of the burglary. In the famous "smoking gun" recording that led to President Nixon's resignation, Nixon ordered his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, to tell the CIA that further investigation of Watergate would "open the whole can of worms" about the Bay of Pigs Invasion of Cuba.[77] In this way Nixon and Haldemann ensured that the CIA's No. 1 and No. 2 ranking officials, Richard Helms and Vernon Walters, communicated to FBI Director L. Patrick Gray that the FBI should not follow the money trail from the burglars to the Committee to Re-elect the President, as it would uncover CIA informants in Mexico. The FBI initially agreed to this due to a long-standing agreement between the FBI and CIA not to uncover each other's sources of information, though within a couple of weeks the FBI demanded this request in writing, and when no such formal request came, the FBI resumed its investigation into the money trail. Nonetheless, when the smoking gun tapes were made public, damage to the public's perception of CIA's top officials, and thus to the CIA as a whole, could not be avoided.[78]

In 1973, then-Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) James R. Schlesinger commissioned reports – known as the "Family Jewels" – on illegal activities by the Agency. In December 1974, investigative journalist Seymour Hersh broke the news of the "Family Jewels" (after it was leaked to him by DCI William Colby) in a front-page article in The New York Times, claiming that the CIA had assassinated foreign leaders, and had illegally conducted surveillance on some 7,000 U.S. citizens involved in the antiwar movement (Operation CHAOS).[76] The CIA had also experimented on U.S. and Canadian citizens without their knowledge, secretly giving them LSD (among other things) and observing the results.[76]

Congress responded to the disturbing charges in 1975, investigating the CIA in the Senate via the Church Committee, chaired by Senator Frank Church (D-Idaho), and in the House of Representatives via the Pike Committee, chaired by Congressman Otis Pike (D-NY).[76] In addition, President Gerald Ford created the Rockefeller Commission,[76] and issued an executive order prohibiting the assassination of foreign leaders.

During the investigation, Schlesinger's successor as DCI, William Colby, testified before Congress on 32 occasions in 1975, including about the "Family Jewels".[79] Colby later stated that he believed that providing Congress with this information was the correct thing to do, and ultimately in the CIA's own interests.[80] As the CIA fell out of favor with the public, Ford assured Americans that his administration was not involved: "There are no people presently employed in the White House who have a relationship with the CIA of which I am personally unaware."[76]

Repercussions from the Iran-Contra affair arms smuggling scandal included the creation of the Intelligence Authorization Act in 1991. It defined covert operations as secret missions in geopolitical areas where the U.S. is neither openly nor apparently engaged. This also required an authorizing chain of command, including an official, presidential finding report and the informing of the House and Senate Intelligence Committees, which, in emergencies, requires only "timely notification."

2004, DNI takes over CIA top-level functions

The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 created the office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), who took over some of the government and intelligence community (IC)-wide functions that had previously been the CIA's. The DNI manages the United States Intelligence Community and in so doing it manages the intelligence cycle. Among the functions that moved to the DNI were the preparation of estimates reflecting the consolidated opinion of the 16 IC agencies, and preparation of briefings for the president. On July 30, 2008, President Bush issued Executive Order 13470[81] amending Executive Order 12333 to strengthen the role of the DNI.[82]

Previously, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) oversaw the Intelligence Community, serving as the president's principal intelligence advisor, additionally serving as head of the CIA. The DCI's title now is "Director of the Central Intelligence Agency" (D/CIA), serving as head of the CIA.

Currently, the CIA reports to the Director of National Intelligence. Prior to the establishment of the DNI, the CIA reported to the President, with informational briefings to congressional committees. The National Security Advisor is a permanent member of the National Security Council, responsible for briefing the President with pertinent information collected by all U.S. intelligence agencies, including the National Security Agency, the Drug Enforcement Administration, etc. All 16 Intelligence Community agencies are under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence.

Al-Qaeda and the "Global War on Terrorism"

The CIA had long been dealing with terrorism originating from abroad, and in 1986 had set up a Counterterrorist Center to deal specifically with the problem. At first confronted with secular terrorism, the Agency found Islamist terrorism looming increasingly large on its scope.

In January 1996, the CIA created an experimental "virtual station," the Bin Laden Issue Station, under the Counterterrorist Center, to track Bin Laden's developing activities. Al-Fadl, who defected to the CIA in spring 1996, began to provide the Station with a new image of the Al Qaeda leader: he was not only a terrorist financier, but a terrorist organizer, too. FBI Special Agent Dan Coleman (who together with his partner Jack Cloonan had been "seconded" to the Bin Laden Station) called him Qaeda's "Rosetta Stone".[83]

In 1999, CIA chief George Tenet launched a grand "Plan" to deal with al-Qaeda. The Counterterrorist Center, its new chief Cofer Black and the center's Bin Laden unit were the Plan's developers and executors. Once it was prepared Tenet assigned CIA intelligence chief Charles E. Allen to set up a "Qaeda cell" to oversee its tactical execution.[84] In 2000, the CIA and USAF jointly ran a series of flights over Afghanistan with a small remote-controlled reconnaissance drone, the Predator; they obtained probable photos of Bin Laden. Cofer Black and others became advocates of arming the Predator with missiles to try to assassinate Bin Laden and other al-Qaeda leaders. After the Cabinet-level Principals Committee meeting on terrorism of September 4, 2001, the CIA resumed reconnaissance flights, the drones now being weapons-capable.

The CIA set up a Strategic Assessments Branch in 2001 to remedy the deficit of "big-picture" analysis of al-Qaeda, and apparently to develop targeting strategies. The branch was formally set up in July 2001, but it struggled to find personnel. The branch's head took up his job on September 10, 2001.[85][86][87]

Post 9/11:

Soon after 9/11, the New York Times released a story stating that the CIA's New York field office was destroyed in the wake of the attacks. According to unnamed CIA sources, while first responders were conducting rescue efforts, a special CIA team was searching the rubble for both digital and paper copies of classified documents. This was done according to well-rehearsed document recovery procedures put in place after the Iranian takeover of the United States Embassy in Tehran in 1979. While it was not confirmed whether the agency was able to retrieve the classified information, it is known that all agents present that day fled the building safely.

While the CIA insists that those who conducted the attacks on 9/11 were not aware that the agency was operating at 7 World Trade Center under the guise of another (unidentified) federal agency, this center was the headquarter for many notable criminal terrorism investigations. Though the New York field offices' main responsibilities were to monitor and recruit foreign officials stationed at the United Nations, the field office also handled the investigations of the August 1998 bombings of United States Embassies in East Africa and the October 2000 bombing of the U.S.S Cole.[88] Despite the fact that the CIA's New York branch may have been damaged by the 9/11 attacks and they had to loan office space from the US Mission to the United Nations and other federal agencies, there was an upside for the CIA.[88] In the months immediately following 9/11, there was a huge increase in the amount of applications for CIA positions. According to CIA representatives that spoke with the New York Times, pre-9/11 the agency received approximately 500 to 600 applications a week, in the months following 9/11 the agency received that number daily.[89]

The intelligence community as a whole, and especially the CIA, were involved in presidential planning immediately after the 9/11 attacks. In his address to the nation at 8:30pm on September 11, 2001 George W. Bush mentioned the intelligence community: "The search is underway for those who are behind these evil acts, I've directed the full resource of our intelligence and law enforcement communities to find those responsible and bring them to justice." [90]

The involvement of the CIA in the newly coined "War on Terror" was further increased on September 15, 2001. During a meeting at Camp David George W. Bush agreed to adopt a plan proposed by CIA director George Tenet. This plan consisted of conducting a covert war in which CIA paramilitary officers would cooperate with anti-Taliban guerillas inside Afghanistan. They would later be joined by small special operations forces teams which would call in precision airstrikes on Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters. This plan was codified on September 16, 2001 with Bush's signature of an official Memorandum of Notification that allowed the plan to proceed.[91]

On November 25–27, 2001 Taliban prisoners revolt at the Qala Jangi prison west of Mazar-e-Sharif. Though several days of struggle occurred between the Taliban prisoners and the Northern Alliance members present, the prisoners did gain the upperhand and obtain North Alliance weapons. At some point during this period Johnny "Mike" Spann, a CIA agent sent to question the prisoners, was beaten to death. He became the first American to die in combat in the war in Afghanistan.[91]

After 9/11, the CIA came under criticism for not having done enough to prevent the attacks. Tenet rejected the criticism, citing the Agency's planning efforts especially over the preceding two years. He also considered that the CIA's efforts had put the Agency in a position to respond rapidly and effectively to the attacks, both in the "Afghan sanctuary" and in "ninety-two countries around the world".[92] The new strategy was called the "Worldwide Attack Matrix".

Anwar al-Awlaki, a Yemeni-American U.S. citizen and al-Qaeda member, was killed on September 30, 2011, by an air attack carried out by the Joint Special Operations Command. After several days of surveillance of Awlaki by the Central Intelligence Agency, armed drones took off from a new, secret American base in the Arabian Peninsula, crossed into northern Yemen, and unleashed a barrage of Hellfire missiles at al-Awlaki's vehicle. Samir Khan, a Pakistani-American al-Qaeda member and editor of the jihadist Inspire magazine, also reportedly died in the attack. The combined CIA/JSOC drone strike was the first in Yemen since 2002 – there have been others by the military’s Special Operations forces – and was part of an effort by the spy agency to duplicate in Yemen the covert war which has been running in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[93][94]

2003 War in Iraq

Whether or not the intelligence available, or presented by the Bush Administration, justified the 2003 invasion of Iraq or allowed proper planning, especially for the occupation, is quite controversial.[95] However, there was more than one CIA employee that asserted the sense that Bush administration officials placed undue pressure on CIA analysts to reach certain conclusions that would support their stated policy positions with regard to Iraq.[96]

CIA Special Activities Division paramilitary teams were the first teams in Iraq arriving in July 2002. Once on the ground they prepared the battle space for the subsequent arrival of U.S. military forces. SAD teams then combined with U.S. Army Special Forces (on a team called the Northern Iraq Liaison Element or NILE).[97] This team organized the Kurdish Peshmerga for the subsequent U.S.-led invasion. They combined to defeat Ansar al-Islam, an ally of Al-Qaeda. If this battle had not been as successful as it was, there would have been a considerable hostile force behind the U.S./Kurdish force in the subsequent assault on Saddam's Army. The U.S. side was carried out by Paramilitary Operations Officers from SAD/SOG and the Army's 10th Special Forces Group.[97][98][99]

SAD teams also conducted high-risk special reconnaissance missions behind Iraqi lines to identify senior leadership targets. These missions led to the initial strikes against Saddam Hussein and his key generals. Although the initial strike against Hussein was unsuccessful in killing the dictator, it was successful in effectively ending his ability to command and control his forces. Other strikes against key generals were successful and significantly degraded the command's ability to react to and maneuver against the U.S.-led invasion force.[97][100]

NATO member Turkey refused to allow its territory to be used by the U.S. Army's 4th Infantry Division for the invasion. As a result, the SAD, U.S. Army Special Forces joint teams and the Kurdish Peshmerga were the entire northern force against Saddam's Army during the invasion. Their efforts kept the 1st and 5th Corps of the Iraqi Army in place to defend against the Kurds rather than their moving to contest the coalition force coming from the south. This combined U.S. Special Operations and Kurdish force soundly defeated Saddam's Army, a major military success, similar to the victory over the Taliban in Afghanistan.[97] Four members of the SAD/SOG team received CIA's rare Intelligence Star for their "heroic actions."[101]

Operation Neptune Spear

On May 1, 2011, President Barack Obama announced that Osama bin Laden was killed earlier that day by "a small team of Americans" operating in Abbottabad, Pakistan, during a CIA operation.[102][103] The raid was executed from a CIA forward base in Afghanistan by elements of the U.S. Navy's Naval Special Warfare Development Group and CIA paramilitary operatives.[104]

It resulted in the acquisition of extensive intelligence on the future attack plans of al-Qaeda.[105][106][107] The operation was a result of years of intelligence work that included the CIA's capture and interrogation of Khalid Sheik Mohammad (KSM), which led to the identity of a courier of Bin Laden's,[108][109][110] the tracking of the courier to the compound by Special Activities Division paramilitary operatives and the establishing of a CIA safe house to provide critical tactical intelligence for the operation.[111][112][113]

Open Source Intelligence

Until the 2004 reorganization of the intelligence community, one of the "services of common concern" that the CIA provided was Open Source Intelligence from the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS).[114] FBIS, which had absorbed the Joint Publication Research Service, a military organization that translated documents,[115] moved into the National Open Source Enterprise under the Director of National Intelligence.

The CIA still provides a variety of unclassified maps and reference documents both to the intelligence community and the public.[116]

During the Reagan administration, Michael Sekora (assigned to the DIA), worked with agencies across the intelligence community, including the CIA, to develop and deploy a technology-based competitive strategy system called Project Socrates. Project Socrates was designed to utilize open source intelligence gathering almost exclusively. The technology-focused Socrates system supported such programs as the Strategic Defense Initiative in addition to private sector projects.[117][118]

As part of its mandate to gather intelligence, the CIA is looking increasingly online for information, and has become a major consumer of social media. "We're looking at YouTube, which carries some unique and honest-to-goodness intelligence," said Doug Naquin, director of the DNI Open Source Center (OSC) at CIA headquarters. "We're looking at chat rooms and things that didn't exist five years ago, and trying to stay ahead."[119]

Outsourcing and privatization

Many of the duties and functions of Intelligence Community activities, not the CIA alone, are being outsourced and privatized. Mike McConnell, former Director of National Intelligence, was about to publicize an investigation report of outsourcing by U.S. intelligence agencies, as required by Congress.[120] However, this report was then classified.[121][122] Hillhouse speculates that this report includes requirements for the CIA to report:[121][123]

- different standards for government employees and contractors;

- contractors providing similar services to government workers;

- analysis of costs of contractors vs. employees;

- an assessment of the appropriateness of outsourced activities;

- an estimate of the number of contracts and contractors;

- comparison of compensation for contractors and government employees;

- attrition analysis of government employees;

- descriptions of positions to be converted back to the employee model;

- an evaluation of accountability mechanisms;

- an evaluation of procedures for "conducting oversight of contractors to ensure identification and prosecution of criminal violations, financial waste, fraud, or other abuses committed by contractors or contract personnel"; and

- an "identification of best practices of accountability mechanisms within service contracts."

According to investigative journalist Tim Shorrock:

...what we have today with the intelligence business is something far more systemic: senior officials leaving their national security and counterterrorism jobs for positions where they are basically doing the same jobs they once held at the CIA, the NSA and other agencies — but for double or triple the salary, and for profit. It's a privatization of the highest order, in which our collective memory and experience in intelligence — our crown jewels of spying, so to speak — are owned by corporate America. Yet, there is essentially no government oversight of this private sector at the heart of our intelligence empire. And the lines between public and private have become so blurred as to be nonexistent.[124][125]

Congress has required an outsourcing report by March 30, 2008.[123]

The Director of National Intelligence has been granted the authority to increase the number of positions (FTEs) on elements in the Intelligence Community by up to 10% should there be a determination that activities performed by a contractor should be done by a US government employee."[123]

Part of the contracting problem comes from Congressional restrictions on the number of employees in the IC. According to Hillhouse, this resulted in 70% of the de facto workforce of the CIA's National Clandestine Service being made up of contractors. "After years of contributing to the increasing reliance upon contractors, Congress is now providing a framework for the conversion of contractors into federal government employees—more or less."[123]

As with most government agencies, building equipment often is contracted. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), responsible for the development and operation of airborne and spaceborne sensors, long was a joint operation of the CIA and the United States Department of Defense. NRO had been significantly involved in the design of such sensors, but the NRO, then under DCI authority, contracted more of the design that had been their tradition, and to a contractor without extensive reconnaissance experience, Boeing. The next-generation satellite Future Imagery Architecture project "how does heaven look", which missed objectives after $4 billion in cost overruns, was the result of this contract.[126][127]

Some of the cost problems associated with intelligence come from one agency, or even a group within an agency, not accepting the compartmented security practices for individual projects, requiring expensive duplication.[128]

Controversies

Major sources for this section include the Council on Foreign Relations of the United States series, the National Security Archive and George Washington University, the Freedom of Information Act Reading Room at the CIA, U.S. Congressional hearings, and books by William Blum[129] and Tim Weiner.[21] Note that the CIA has responded to the claims made in Weiner's book,[130] and that Jeffrey Richelson of the National Security Archive has also been critical of it.[131]

Areas of controversy about inappropriate, often illegal actions include experiments, without consent, on human beings to explore chemical means of eliciting information or disabling people. Another area involved torture and clandestine imprisonment. There have been attempted assassinations under CIA orders and support for assassinations of foreign leaders by citizens of the leader's country, and, in a somewhat different legal category that may fall under the customary laws of war, assassinations of militant leaders.

Extraordinary rendition

Extraordinary rendition is the apprehension and extrajudicial transfer of a person from one country to another.[132]

The term "torture by proxy" is used by some critics to describe situations in which the CIA[133][134][135][136] and other US agencies have transferred suspected terrorists to countries known to employ torture, whether they meant to enable torture or not. It has been claimed, though, that torture has been employed with the knowledge or acquiescence of US agencies (a transfer of anyone to anywhere for the purpose of torture is a violation of US law), although Condoleezza Rice (then the United States Secretary of State) stated that:[137]

“the United States has not transported anyone, and will not transport anyone, to a country when we believe he will be tortured. Where appropriate, the United States seeks assurances that transferred persons will not be tortured."

Whilst the Obama administration has tried to distance itself from some of the harshest counterterrorism techniques, it has also said that at least some forms of renditions will continue.[138] Currently the administration continues to allow rendition only "to a country with jurisdiction over that individual (for prosecution of that individual)" when there is a diplomatic assurance "that they will not be treated inhumanely."[139][140]

The US programme has also prompted several official investigations in Europe into alleged secret detentions and unlawful inter-state transfers involving Council of Europe member states. A June 2006 report from the Council of Europe estimated 100 people had been kidnapped by the CIA on EU territory (with the cooperation of Council of Europe members), and rendered to other countries, often after having transited through secret detention centres ("black sites") used by the CIA, some located in Europe. According to the separate European Parliament report of February 2007, the CIA has conducted 1,245 flights, many of them to destinations where suspects could face torture, in violation of article 3 of the United Nations Convention Against Torture.[141]

Following the 11 September 2001 attacks the United States, in particular the CIA, has been accused of rendering hundreds of people suspected by the government of being terrorists—or of aiding and abetting terrorist organisations—to third-party states such as Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Uzbekistan. Such "ghost detainees" are kept outside judicial oversight, often without ever entering US territory, and may or may not ultimately be devolved to the custody of the United States.[142][143]

On October 4, 2001, a secret arrangement is made in Brussels, by all members of NATO. Lord George Robertson, British defence secretary and later NATO’s secretary-general, will later explain NATO members agree to provide “blanket overflight clearances for the United States and other allies’ aircraft for military flights related to operations against terrorism.”[144]

Security and counterintelligence failures

While the names change periodically, there are two basic security functions to protect the CIA and its operations. There is an Office of Security in the Directorate for Support, which is responsible for physical security of the CIA buildings, secure storage of information, and personnel security clearances. These are directed inwardly to the agency itself.

In what is now the National Clandestine Service, there is a counterintelligence function, called the Counterintelligence Staff under James Jesus Angleton. This function has roles including looking for staff members that are providing information to foreign intelligence services (FIS) as moles. Another role is to check proposals for recruiting foreign HUMINT assets, to see if these people have any known ties to FIS and thus may be attempts to penetrate CIA to learn its personnel and practices, or as a provocateur, or other form of double agent.

This agency component may also launch offensive counterespionage, where it attempts to interfere with FIS operations. CIA officers in the field often have assignments in offensive counterespionage as well as clandestine intelligence collection.

Security failures

The "Family Jewels" and other documents reveal that the Office of Security violated the prohibition of CIA involvement in domestic law enforcement, sometimes with the intention of assisting police organizations local to CIA buildings.

On December 30, 2009, a suicide attack occurred in the Forward Operating Base Chapman attack, a major CIA base in the province of Khost, Afghanistan. Seven CIA officers, including the chief of the base, were killed and six others seriously wounded in the attack. The CIA is consequently conducting an investigation into how the suicide bomber managed to avoid the base's security measures.[145]

Counterintelligence failures

Perhaps the most disruptive period involving counterintelligence was James Jesus Angleton's search for a mole,[146] based on the statements of a Soviet defector, Anatoliy Golitsyn. A second defector, Yuri Nosenko, challenged Golitsyn's claims, with the two calling one another Soviet double agents.[147] Many CIA officers fell under career-ending suspicion; the details of the relative truths and untruths from Nosenko and Golitsyn may never be released, or, in fact, may not be fully understood. The accusations also crossed the Atlantic to the British intelligence services, who also were damaged by molehunts.[148]

On February 24, 1994, the agency was rocked by the arrest of 31-year veteran case officer Aldrich Ames on charges of spying for the Soviet Union since 1985.[149]

Other defectors have included Edward Lee Howard, David Henry Barnett, both field operations officers, and William Kampiles, a low-level worker in the CIA 24-hour Operations Center. Kampiles sold the Soviets the detailed operational manual for the KH-11 reconnaissance satellite.[150]

Failures in intelligence analysis

The agency has also been criticized by some for ineffectiveness as an intelligence gathering agency. Former DCI Richard Helms commented, after the end of the Cold War, "The only remaining superpower doesn't have enough interest in what's going on in the world to organize and run an espionage service."[151] The CIA has come under particular criticism for failing to predict the collapse of the Soviet Union.[citation needed]

See the information technology section of the intelligence analysis management for discussion of possible failures to provide adequate automation support to analysts, and A-Space for a IC-wide program to collect some of them. Cognitive traps for intelligence analysis also goes into areas where CIA has examined why analysis can fail.

Agency veterans, such as John McLaughlin, who was deputy director and acting director of central intelligence from October 2000 to September 2004 have lamented CIA's inability to produce the kind of long-range strategic intelligence that it once did in order to guide policymakers. McLaughlin notes that CIA is drowned by demands from the White House and Pentagon for instant information, and said, "intelligence analysts end up being the Wikipedia of Washington."[152] In the intelligence analysis article, orienting oneself to the consumers deals with some ways in which intelligence can become more responsive to the needs of policymakers.

For the media, the failures are most newsworthy. A number of declassified National Intelligence Estimates do predict the behavior of various countries, but not in a manner attractive to news, or, most significantly, not public at the time of the event. In its operational role, some successes for the CIA include the U-2 and SR-71 programs, and anti-Soviet operations in Afghanistan in the mid-1980s.

Among the first analytic failures, before the CIA had its own collection capabilities, it assured President Harry S. Truman on October 13, 1950 that the Chinese would not send troops to Korea. Six days later, over one million Chinese troops arrived.[153] -->

The history of U.S. intelligence, with respect to French Indochina and then the two Vietnams, is long and complex. The Pentagon Papers often contain pessimistic CIA analyses that conflicted with White House positions. It does appear that some estimates were changed to reflect Pentagon and White House views.[75] See CIA activities in Asia and the Pacific for detailed discussions of intelligence and covert operations from 1945 (i.e., before the CIA) onwards.

Another criticism is the failure to predict India's nuclear tests in 1974. A review of the various analyses of India's nuclear program did predict some aspects of the test, such as a 1965 report saying, correctly, that if India did develop a bomb, it would be explained as "for peaceful purposes".

A major criticism is failure to forestall the September 11 attacks. The 9/11 Commission Report identifies failures in the IC as a whole. One problem, for example, was the FBI failing to "connect the dots" by sharing information among its decentralized field offices. The report, however, criticizes both CIA analysis, and impeding their investigation.

The executive summary of a report which was released by the office of CIA Inspector General John Helgerson on August 21, 2007 concluded that former DCI George Tenet failed to adequately prepare the agency to deal with the danger posed by Al-Qaeda prior to the attacks of September 11, 2001. The report had been completed in June 2005 and was partially released to the public in an agreement with Congress, over the objections of current DCI General Michael Hayden. Hayden said its publication would "consume time and attention revisiting ground that is already well plowed."[154] Tenet disagreed with the report's conclusions, citing his planning efforts vis-à-vis al-Qaeda, particularly from 1999.[155]

Human rights concerns

The CIA has been called into question on several occasions for some of the tactics it employs to carry out its missions. At times these tactics have included torture, funding and training of groups and organizations that would later participate in killing of civilians and other non-combatants and would try or succeed in overthrowing democratically elected governments, human experimentation, and targeted killings and assassinations.

The CIA has been criticized for ineffectiveness in its basic mission of intelligence gathering. A variant of this criticism is that allegations of misconduct are symptomatic of lack of attention to basic mission in the sense that controversial actions, such as assassination attempts and human rights violations, tend to be carried out in operations that have little to do with intelligence gathering. The CIA has been charged with having more than 90% of its employees living and working within the United States, rather than in foreign countries, which is in violation of its charter. The CIA has also been accused of a lack of financial and whistleblower controls which has led to waste and fraud.[156]

One of the most recent developments in the study of the Central Intelligence Agency and the post 9/11 war on terror comes in the form of a joint report from a panel of 19 doctors, lawyers, and human rights experts sponsored by “the Columbia University-based think tank Institute on Medicine as a Profession and the non-profit organization Open Society Foundations” with the purpose of “reviewing public records into the medical professions’ alleged complicity in the abuse of prisoners suspected of terrorism who were held in U.S. custody during the years after 9/11.”[157][158] This report was the product of over two years of investigation and had several major findings.

Among the reports' findings are that health professionals “Aided cruel and degrading interrogations; Helped devise and implement practices designed to maximize disorientation and anxiety so as to make detainees more malleable for interrogation; and Participated in the application of excruciatingly painful methods of force-feeding of mentally competent detainees carrying out hunger strikes” are not all that surprising.[157] It is known that medical professionals were sometimes used at C.I.A. black sites in order to monitor detainee health. In fact, it was so prevalent that one record states a medical professional examined a specific detainee nine times in a matter of two weeks.[159] What is significant about the report is that it has sparked a debate regarding whether or not the physicians were compelled.

External investigations and document releases

At various times since the creation of the CIA, the U.S. government has produced comprehensive reports on CIA actions that marked historical watersheds in how CIA went about trying to fulfill its vague charter purposes from 1947. These reports were the result of internal/presidential studies, external investigations by Congressional committees or other arms of the US Government, or even the simple releases and declassification of large quantities of documents by the CIA.

Several investigations (e.g., the Church Committee, Rockefeller Commission, Pike Committee, etc.), as well as released declassified documents, reveal that the CIA, at times, operated outside its charter. In some cases, such as during Watergate, this may have been due to inappropriate requests by White House staff. In other cases, there was a violation of Congressional intent, such as the Iran-Contra affair. In many cases, these reports provide the only official discussion of these actions available to the public.[160]

Influencing public opinion and law enforcement

The CIA has much popular agreement in a set few instances wherein it has acted inappropriately, such as in providing technical support to White House operatives conducting both political and security investigations, with no reputed legal authority to do so. In many cases, ambiguity existing between law enforcement and intelligence agencies may expose a clandestine operation. This is a problem not unique to intelligence but also seen among different law enforcement organizations, where one wants to prosecute and another to continue investigations, perhaps reaching higher levels in a conspiracy.[161]

Drug trafficking

Two offices of CIA Directorate of Intelligence have analytical responsibilities in this area. The Office of Transnational Issues[35] applies unique functional expertise to assess existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security and provides the most senior U.S. policymakers, military planners, and law enforcement with analysis, warning, and crisis support.

CIA Crime and Narcotics Center[36] researches information on international narcotics trafficking and organized crime for policymakers and the law enforcement community. Since CIA has no domestic police authority, it sends its analytic information to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other law enforcement organizations, such as the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the United States Department of the Treasury (OFAC).

Another part of CIA, the National Clandestine Service, collects human intelligence (HUMINT) in these areas.

Research by Dr. Alfred W. McCoy, Gary Webb, and others has pointed to CIA involvement in narcotics trafficking across the globe, although the CIA officially denies such allegations.[162][163] During the Cold War, when numerous soldiers participated in transport of Southeast Asian heroin to the United States by the airline Air America[citation needed], the CIA's role in such traffic was reportedly rationalized as "recapture" of related profits to prevent possible enemy control of such assets.

Lying to Congress

Former Speaker of the United States House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi has stated that the CIA repeatedly misled the Congress since 2001 about waterboarding and other torture, though Pelosi admitted to being told about the programs.[164][165] Six members of Congress have claimed that Director of CIA Leon Panetta admitted that over a period of several years since 2001 the CIA deceived Congress, including affirmatively lying to Congress. Some congressmen believe that these "lies" to Congress are similar to CIA lies to Congress from earlier periods.[166]

Covert programs hidden from Congress

On July 10, 2009, House Intelligence subcommittee Chairwoman Representative Jan Schakowsky (D, IL) announced the termination of an unnamed CIA covert program described as "very serious" in nature which had been kept secret from Congress for eight years.[167]

"It's not as if this was an oversight and over the years it just got buried. There was a decision under several directors of the CIA and administration not to tell the Congress."

Jan Schakowsky, Chairwoman, U.S. House of Representatives Intelligence Subcommittee

CIA Director Panetta had ordered an internal investigation to determine why Congress had not been informed about the covert program. Chairman of the House Intelligence Committee Representative Silvestre Reyes announced that he is considering an investigation into alleged CIA violations of the National Security Act, which requires with limited exception that Congress be informed of covert activities. Investigations and Oversight Subcommittee Chairwoman Schakowsky indicated that she would forward a request for congressional investigation to HPSCI Chairman Silvestre Reyes.

"Director Panetta did brief us two weeks ago—I believe it was on the 24th of June—... and, as had been reported, did tell us that he was told that the vice president had ordered that the program not be briefed to the Congress."

Dianne Feinstein, Chairwoman of the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence

As mandated by Title 50 of the United States Code Chapter 15, Subchapter III, when it becomes necessary to limit access to covert operations findings that could affect vital interests of the U.S., as soon as possible the President must report at a minimum to the Gang of Eight (the leaders of each of the two parties from both the Senate and House of Representatives, and the chairs and ranking members of both the Senate Committee and House Committee for intelligence).[168] The House is expected to support the 2010 Intelligence Authorization Bill including a provision that would require the President to inform more than 40 members of Congress about covert operations. The Obama administration threatened to veto the final version of a bill that included such a provision.[169][170] On July 16, 2008 the fiscal 2009 Intelligence Authorization Bill was approved by House majority containing stipulations that 75% of money sought for covert actions would be held until all members of the House Intelligence panel were briefed on sensitive covert actions. Under the George W. Bush administration, senior advisers to the President issued a statement indicating that if a bill containing this provision reached the President, they would recommend that he veto the bill.[171]

The program was rumored vis-à-vis leaks made by anonymous government officials on July 23, to be an assassinations program,[172][173] but this remains unconfirmed. "The whole committee was stunned....I think this is as serious as it gets," stated Anna Eshoo, Chairman, Subcommittee on Intelligence Community Management, U.S. House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI).

Allegations by Director Panetta indicate that details of a secret counterterrorism program were withheld from Congress under orders from former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney. This prompted Senator Feinstein and Senator Patrick Leahy, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee to insist that no one should go outside the law.[174] "The agency hasn't discussed publicly the nature of the effort, which remains classified," said agency spokesman Paul Gimigliano.[175]

The Wall Street Journal reported, citing former intelligence officials familiar with the matter, that the program was an attempt to carry out a 2001 presidential authorization to capture or kill al-Qaeda operatives.[176]

Intelligence Committee investigation

On July 17, 2009, the House Intelligence Committee said it was launching a formal investigation into the secret program.[177] Representative Silvestre Reyes announced the probe will look into "whether there was any past decision or direction to withhold information from the committee".

"Is giving your kid a test in school an inhibition on his free learning?" Holt said. "Sure, there are some people who are happy to let intelligence agencies go about their business unexamined. But I think most people when they think about it will say that you will get better intelligence if the intelligence agencies don't operate in an unexamined fashion."

Rush Holt, Chairman, House Select Intelligence Oversight Panel, Committee on Appropriations[178]

Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky (D, IL), Chairman of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, who called for the investigation, stated that the investigation was intended to address CIA failures to inform Congress fully or accurately about four issues: C.I.A. involvement in the downing of a missionary plane mistaken for a narcotics flight in Peru in 2001, and two "matters that remain classified", as well as the rumored-assassinations question. In addition, the inquiry is likely to look at the Bush administration's program of eavesdropping without warrants and its detention and interrogation program.[179] U.S. Intelligence Chief Dennis Blair testified before the House Intelligence Committee on February 3, 2010 that the U.S. intelligence community is prepared to kill U.S. citizens if they threaten other Americans or the United States.[180] The American Civil Liberties Union has said this policy is "particularly troubling" because U.S. citizens "retain their constitutional right to due process even when abroad." The ACLU also "expressed serious concern about the lack of public information about the policy and the potential for abuse of unchecked executive power."[181]

See also

- Covert United States foreign regime change actions

- Defense Intelligence Agency

- National Geospatial‐Intelligence Agency

- National Intelligence Board

- National Reconnaissance Office

- National Security Agency

- Project MKUltra

- Reagan Doctrine

- Secret Intelligence Service

- The World Factbook, published by the CIA

- Abu Omar case

- CIA in fiction

References

- ^ History of the CIA, CIA official Web site

- ^ "CIA Observes 50th Anniversary of Original Headquarters Building Cornerstone Laying – Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ "CIA Frequently Asked Questions". cia.gov. July 28, 2006. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gellman, Barton (August 29, 2013). "U.S. spy network's successes, failures and objectives detailed in 'black budget' summary". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kopel, Dave (July 35, 1997). "CIA Budget: An Unnecessary Secret". Retrieved 2007-04-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Cloak Over the CIA Budget". November 29, 1999. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- ^ "McLean CDP, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on September 1, 2009.

- ^ "Presence, not Performance". United States Airforce Magazine Online. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ^ Adam J. Hebert. "PRESENCE, Not Performance" (PDF). www.afa.org. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ Richard A. Best, Jr. (December 11, 2012). "Director of National Intelligence Statutory Authorities: Status and Proposals" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved September 3, 2012.

- ^ Caroline Wilbert. "How the CIA Works". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ Aftergood, Steven (October 6, 2011). "Reducing Overclassification Through Accountability". Federation of American Scientists Secrecy News. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ Woodward, Bob (November 18, 2001). "Secret CIA Units Playing Central Combat Role". Washington Post. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ^ "World Leaders-Paraguay". United States Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ Eimer, Charlotte (September 28, 2005). "Spotlight on US troops in Paraguay". BBC News. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (October 23, 2006). "Paraguay in a spin about Bush's alleged 100,000 acre hideaway". The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ Commission on the Roles and Capabilities of the United States Intelligence Community. "Preparing for the 21st Century: An Appraisal of U.S. Intelligence".

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ Barton Gellman and Ellen Nakashima. "U.S. spy agencies mounted 231 offensive cyber-operations in 2011, documents show". The Washington Post.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kinzer, Stephen (2008). All the Shah's men. ISBN 0-471-26517-9.

- ^ "Office of Policy Coordination 1948–1952" (PDF). 1952. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ a b Weiner, Tim (2007). Legacy of Ashes. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51445-3.

- ^ Ion Mihai Pacepa, A Matter of Trust, National Review, March 1, 2004.

- ^ "CIA Support to the US Military During the Persian Gulf War". Central Intelligence Agency. June 16, 1997.

- ^ "CIA Abbreviations and Acronyms". Cia.gov. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ Reiss Jr, Robert J. Jr. (2006 Summer Edition). "The C2 puzzle: Space Authority and the Operational Level of War" (PDF). Army Space Journal.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)[dead link] - ^ "Center for the Study of Intelligence". cia.gov. July 16, 2006.[dead link]

- ^ "Kent Center Occasional Papers". cia.gov.[dead link]

- ^ Warrick, Joby (February 2, 2008). "CIA Sets Changes To IG's Oversight, Adds Ombudsman". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark (February 2, 2008). "C.I.A. Tells of Changes for Its Internal Inquiries". The New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Patterson, John (October 5, 2001). "Hollywood reporter: The caring, sharing CIA: Central Intelligence gets a makeover". Guardian (UK). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ "Fifty Years of Service to the Nation". cia.gov. July 16, 2006.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency. "Intelligence & Analysis". Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ "Office of Terrorism Analysis".

- ^ "Antiterrorism intelligence at work in Iraq (Youtube: Collateral Murder)". WikiLeaks. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "Office of Transnational Issues".

- ^ a b "CIA Crime and Narcotics Center".

- ^ "Weapons Intelligence, Nonproliferation, and Arms Control Center".

- ^ "Counterintelligence Center Analysis Group".

- ^ "Information Operations Center Analysis Group".

- ^ Miller, Greg, ed. (December 1, 2012). "DIA to send hundreds more spies overseas". The Washington Post.

- ^ Blanton, Thomas S.; Martin, Michael L. (July 17, 2000). "Defense HUMINT Service Organizational Chart". The "Death Squad Protection" Act: Senate Measure Would Restrict Public Access to Crucial Human Rights Information Under the Freedom of Information Act.