Abdominopelvic cavity

| Abdominopelvic cavity | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cavitas abdominis et pelvis |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.050 A10.1.00.000 |

| TA2 | 3699 |

| FMA | 12267 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The abdominopelvic cavity is a body cavity that consists of the abdominal cavity and the pelvic cavity.[1] The upper portion is the abdominal cavity, and it contains the stomach, liver, pancreas, spleen, gallbladder, kidneys, small intestine, and most of the large intestine. The lower portion is the pelvic cavity, and it contains the urinary bladder, the rest of the large intestine (the lower portion), and the internal reproductive organs.[2][3]

There is no membrane that separates out the abdominal cavity from the pelvic cavity, so the terms abdominal pelvis and peritoneal cavity are sometimes used.

There are many diseases and disorders associated with the organs of the abdominopelvic cavity.

Structure and physiology

[edit]The stomach sits on the left side, which is attached to the esophagus tube. Food comes through the esophagus, goes behind all of the other organs in the thoracic cavity, and comes out through the point where the esophagus opens up into the stomach. The stomach is a more acidic environment to aid its role in beginning the major processes of digestion. The bolus must be mechanically and chemically broken down before entering the small intestine.

The small intestine is about 20 feet long and goes behind the large intestine, forming a mass of curly tubing. It is divided into three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and the ileum. The duodenum receives excretions from various organs such as the pancreas and spleen. The pancreas produces the hormone insulin, which helps regulate blood sugar.[4][5] The second part is the jejunum, which is located in the middle of the small intestine. The final part of the small intestine is the ileum, which leads into the large intestine. The ileum leads to the ileum cecum valve, which is the beginning of the large intestine. The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and of the digestive system.

The liver lies in the right hypochondrium area and the greater portion of the epigastric areas of the abdominal cavity under the diaphragm but within the rib cage.[6] It is primarily a processing and detoxifying organ,[7] filtering blood and extracting or breaking down waste and toxins from the bloodstream.[8]

The gallbladder is located on the undersurface of the right lobe of the liver.[9] It produces bile, which is used to help process fats in the body.[9] Humans can live without the gallbladder.[10]

The largest lymphatic organ is the spleen, which is dark purple and located under the lower ribs, around the left side of the upper abdomen.[11][12] It filters the red blood cells by extracting old cells.[11][12]

Coming off the side of the cecum (the tiny tail piece) is the appendix. It is a small organ attached to the large intestine in the lower right side of the abdomen. Anatomists and medical professionals have traditionally considered the appendix a vestigial organ. Later research suggests that it may have an immunological function.[13]

On the dorsal aspect of the abdominal cavity, there are two bean-shaped organs. These are the left and right kidneys. The kidneys filter the blood and urine.

The urinary tract can be divided into the upper urinary tract and the lower urinary tract. The upper urinary tract consists of the kidneys and the ureters, and the lower urinary tract consists of the bladder and the urethra.[14]

Clinical significance

[edit]The stomach can be affected by diseases. Helicobacter pylori, previously known as Campylobacter pylori, is a Gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium infection usually found in the stomach.[15] People who are infected with Campylobacter pylori should drink extra fluids as long as the diarrhea lasts. Antibiotics are needed or prescribed to people who are very ill or at high risk for severe disease, such as people with severely weakened immune systems. This includes people with HIV/AIDS, those receiving chemotherapy, and those with the blood disorders thalassemia and hypogammaglobulinemia.

One disease that affects the lining of the GI tract is Crohn's disease, which is a chronic inflammatory condition.[16] Crohn's most commonly affects the end of the small bowel (the ileum) and the beginning of the colon, but it may affect any part of the GI tract. Crohn's disease affects both the large and small intestine.

Infection of the appendix is appendicitis. When there is a buildup of bacteria, the appendix can get inflamed and swollen, and this leads to appendicitis.

Pancreatitis is the inflammation of the pancreas. Acute pancreatitis is sudden inflammation of the pancreas that may be mild or life-threatening but usually subsides. Gallstones and excessive alcohol use are the main causes of acute pancreatitis. Severe abdominal pain is the predominant symptom.

A person can puncture their spleen if they crack their rib. Because there is a strong flow of blood in the spleen, there is a higher chance of excessive bleeding.

Cirrhosis is a complication of many liver diseases characterized by abnormal structure and function of the liver. The diseases that lead to cirrhosis do so because they injure and kill liver cells, after which the inflammation and repair that is associated with the dying liver cells causes, scar tissue to form. The liver cells that do not die multiply in an attempt to replace the cells that have died. This results in clusters of newly formed liver cells (regenerative nodules) within the scar tissue. A 2008 review states, "The exact prevalence of cirrhosis worldwide is unknown. It was estimated at 0·15% or 400 000 in the USA, 7 which accounted for more than 25000 deaths and 373000 hospital discharges in 1998."[17]

Urinary tract infections are caused by microbes such as bacteria overcoming the body's defenses in the urinary tract.[18] They can affect the kidneys, the bladder, and the tubes that run between them.

A consequence of a fatty diet is diarrhea, due to the fact that the body is no longer processing the food as well.

Additional images

[edit]-

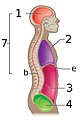

The abdominopelvic cavity 6 is made up of the abdominal cavity 3 and the pelvic cavity 4.

-

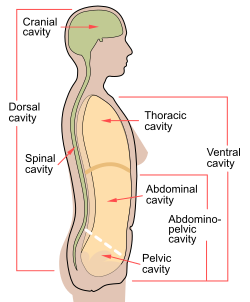

The abdominopelvic cavity is made up of the abdominal cavity 3 and the pelvic cavity 4.

References

[edit]- ^ Rollins, Jeannean Hall; Long, Bruce W.; Curtis, Tammy (2022). Merrill's Atlas of Radiographic Positioning and Procedures - 3-Volume Set - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-32-383323-3.

- ^ Tortora, Gerard J.; Derrickson, Bryan H. (2017). Introduction to the Human Body. John Wiley & Sons. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-11-930666-5.

- ^ Cooper, Kim; Gosnell, Kelly (2014). Foundations and Adult Health Nursing. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1228. ISBN 978-0-32-310001-4.

- ^ Zhang, Liang; Thurber, Greg M. (2017). "Imaging in Diabetes". Imaging and Metabolism. Springer. p. 175. ISBN 978-3-31-961401-4.

- ^ Sarafino, Edward P.; Smith, Timothy W.; King, David B.; Longis, Anita De (2020). Health Psychology: Biopsychosocial Interactions. John Wiley & Sons. p. 462. ISBN 978-1-11-950694-2.

- ^ Reynolds, James C (2016). The Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations: Digestive System: Part III - Liver, etc. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-32-338934-1.

- ^ Patton, Kevin T.; Thibodeau, Gary A. (2018). Anthony's Textbook of Anatomy & Physiology - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 890. ISBN 978-0-32-370930-9.

- ^ Noland, Diana; Drisko, Jeanne A.; Uitgever, Leigh Wagner (2020). Integrative and Functional Medical Nutrition Therapy: Principles and Practices. Springer Nature. p. 206. ISBN 978-3-03-030730-1.

- ^ a b Rifai, Nader (2022). Tietz Textbook of Laboratory Medicine - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 703. ISBN 978-0-32-383467-4.

- ^ Abou-Alfa, Ghassan K.; O'Reilly, Eileen (2013). 100 Questions & Answers About Biliary Cancer. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-28-402538-5.

- ^ a b Abrahams, Peter A (2017). The Human Body. Amber Books Ltd. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-78-274287-6.

- ^ a b Singh, Vishram (2020). Textbook of Anatomy: Abdomen and Lower Limb, Vol 2, 3rd Updated Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 98. ISBN 978-8-13-126248-1.

- ^ Kooij IA, Sahami S, Meijer SL, Buskens CJ, Te Velde AA (October 2016). "The immunology of the vermiform appendix: a review of the literature". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 186 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/cei.12821. PMC 5011360. PMID 27271818.

- ^ Ferrell, Betty Rolling; Paice, Judith A. (2019). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing. Oxford University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-19-086238-1.

- ^ Whittlesea, Cate; Hodson, Karen (2018). Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-70-207010-5.

- ^ Lockhart-Mummery, H. E.; Morson, B. C. (1964). "Crohn's disease of the large intestine". Gut. 5 (6): 493–509. doi:10.1136/gut.5.6.493. PMC 1552156. PMID 14244023.

- ^ Schuppan, Detlef; Afdhal, Nezam H. (2008). "Liver cirrhosis". The Lancet. 371 (9615): 838–851. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. PMC 2271178. PMID 18328931.

- ^ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Aster, Jon (2017). Robbins Basic Pathology E-Book Robbins Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-32-339413-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Graham, David Y. "Campylobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease." Gastroenterology 96.2 (1989): 615–625.

- Lockhart-Mummery, H. E., and B. C. Morson. "Crohn's disease of the large intestine." Gut 5.6 (1964):

- Humes, D. J., and J. Simpson. "Acute appendicitis." Bmj 333.7567 (2006): 530–534.

- Patterson, Jan Evans, and Vincent T. Andriole. "Bacterial urinary tract infections in diabetes." Infectious Disease Clinics 11.3 (1997): 735–750.