Causes of the Holodomor

| Part of a series on the |

| Holodomor |

|---|

The causes of the Holodomor, which was a famine in Soviet Ukraine during 1932 and 1933 that resulted in the death of around 3–5 million people, are the subject of scholarly and political debate, particularly surrounding the Holodomor genocide question. Soviet historians Stephen Wheatcroft and J. Arch Getty believe the famine was the unintended consequence of problems arising from Soviet agricultural collectivization which was designed to accelerate the program of industrialization in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin.[1][2] Other academics conclude policies were intentionally designed to cause the famine.[3][4][5] Some scholars and political leaders claim that the famine may be classified as a genocide under the definition of genocide that entered international law with the 1948 Genocide Convention.[4][5][6][7][8]

Raphael Lemkin, the co-author of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide in 1948, considered Holodomor an attempt to destroy the Ukrainian nation, not just Ukrainian farmers. Such a conclusion was made by him based on four factors:

- the decimation of the Ukrainian national elites,

- the destruction of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church,

- the starvation of the Ukrainian farming population, and

- its replacement with non-Ukrainians from the RSFSR and elsewhere.[9]

Debate on the harvest

[edit]Encyclopædia Britannica says that there was no physical basis for famine in Ukraine, and that Soviet authorities set quotas for Ukraine at exceedingly high levels.[10] According to historian Stanislav Kulchytsky, Ukraine produced more grain in 1930 than the Central Black Earth Oblast, Middle and Lower Volga and North Caucasus regions all together, which had never been done before, and on average gave 4.7 quintals of grain from every sown hectare to the state—a record-breaking index of marketability—but was unable to fulfill the grain quota for 1930 until May 1931. Ukraine produced a similar amount of grain in 1931, but by the late spring of 1932 "many districts were left with no reserves of produce or fodder at all".[11])

According to historian Stephen Wheatcroft, "there were two bad harvests in 1931 and 1932, largely but not wholly a result of natural conditions",[12] within the Soviet Union; Wheatcroft estimates that the grain yield for the Soviet Union preceding the famine was a low harvest of between 55 and 60 million tons,[13]: xix–xxi likely in part caused by damp weather and low traction power,[14] yet official statistics mistakenly (according to Wheatcroft and others) reported a yield of 68.9 million tons.[15] (Note that a single ton of grain is enough to feed 3 people for one year.[16] ) Mark Tauger has suggested an even lower harvest of 45 million tons based on data from 40% of collective farms which has been criticized by other scholars.[15] Wheatcroft suggested that anthropologic hazards such as various agrotechnological failures may have exacerbated the low harvest.[17] Tauger, in contrast, argues that human factors such as low traction power and an exhausted workforce were worse in 1933 than previous years yet that year there had been a higher harvest, so the cause of the low harvest was mostly due to various natural factors.[18]

| Oblast | Total deaths in thousands 1932–1934 |

Deaths per 1000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | ||

| Kiev Oblast | 1110.8 | 13.7 | 178.7 | 7 |

| Kharkov Oblast | 1037.6 | 7.8 | 178.9 | 4.2 |

| Vinnitsia Oblast | 545.5 | 5.9 | 114.6 | 5.2 |

| Dnepropetrovsk Oblast | 368.4 | 5.4 | 91.6 | 4.7 |

| Odessa Oblast | 326.9 | 6.1 | 98.8 | 2.4 |

| Chernigov Oblast | 254.2 | 6 | 75.7 | 11.9 |

| Stalino Oblast | 230.8 | 7 | 41.1 | 6.4 |

| Tiraspol | 68.3 | 9.6 | 102.4 | 8.1 |

The collectivization and high procurement quota explanation for the famine is somewhat called into question by the fact that the oblasts of Ukraine with the highest losses being Kiev and Kharkov which produced far lower amounts of grain than other sections of the country.[20] A potential explanation for this was that Kharkov and Kiev fulfilled and over fulfilled their grain procurements in 1930 which led to raions in these Oblasts having their procurement quotas doubled in 1931 compared to the national average increase in procurement rate of 9%, in fact while Kharkov and Kiev had their quotas increased the Odesa oblast and some raions of Dnepropetrovsk oblast had their procurement quotas decreased.[21] In addition according to Nataliia Levchuk of the Ptoukha Institute of Demography and Social Studies "the distribution of the largely increased 1931 grain quotas in Kharkov and Kiev oblasts by raion was very uneven and unjustified because it was done disproportionally to the percentage of wheat sown area and their potential grain capacity."[21]

Soviet state policies that contributed to the Holodomor

[edit]Dekulakization

[edit]During the 1930s, the Soviet Union was led by Joseph Stalin, who sought to reshape Soviet society from New Economic Policy toward stricter economic planning. As the leader of the Soviet Union, he constructed a state whose policies have been blamed for millions of deaths. A campaign of political repression, including arrests, deportations, and executions of people proclaimed traitors engaged in sabotaging collectivism, often targeted for belonging to specific demographic groups rather than as individuals, occurred from 1929 to 1932. The bourgeois were labelled kulaks and were class enemies. More than 1.8 million peasants were deported in 1930–1931.[22][23][24] This policy was accomplished simultaneously with collectivization in the Soviet Union and effectively brought all agriculture in the Soviet Union under state control. The stated purpose of the campaign was to fight the counter-revolution and build socialism in the countryside.[25]

The "liquidation of the kulaks as a class" was announced by Stalin on 27 December 1929.[22] The decision was formalized in a resolution, "On measures for the elimination of kulak households in districts of comprehensive collectivization", on 30 January 1930. The kulaks were divided into three categories: those to be executed for treason or imprisoned as decided by the local secret political police; those to be exiled for treason to Siberia, the north, the Urals, or Kazakhstan, after determined to be traitors, the government's confiscation of their property occurred; and, those considered traitors or were guilty of terrorism were to be evicted from their houses and used in labour colonies within their own districts.[22]

Blacklisting policy for “malicious bread keepers” was first tested in Ukraine as early as January 1928 as appear in the report of the Izium District Executive Committee in Kharkiv Oblast.[26]

On September 26, 1930, Izvestia communicated a circular letter of the Labor Commissariat of the Highest Council of National Economy, and of the all-union council of trades-unions, which directed to take away from "those harmful bunglers, loafers, and tramp their pay book" - meaning deprive those, who left work on their own will and without acceptable reasons, of their right to work. In Ukraine, however, "harmful loafers and deserters of work" were deprived of the right to receive food products and other necessities from the state as was informed by Izvestia on 11 October 1930.[27]

Fighting Ukrainian Nationalism

[edit]During the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (B) during 26 January – 10 February 1934 the following statement was made:

"There is a controversy as to which deviation represents the chief danger: the deviation towards Great-Russian nationalism, or the deviation towards local nationalism. Under present conditions, this is a formal and, therefore, a pointless controversy. It would be foolish to attempt to give ready-made recipes suitable for all times and for all conditions as regards the chief and the lesser danger. Such recipes do not exist. The chief danger is the deviation against which we have ceased to fight, thereby allowing it to grow into a danger to the state.

In the Ukraine, only very recently, the deviation towards Ukrainian nationalism did not represent the chief danger; but when the fight against it ceased and it was allowed to grow to such an extent that it linked up with the interventionists, this deviation became the chief danger. The question as to which is the chief danger in the sphere of the national question is determined not by futile, formal controversies, but by a Marxist analysis of the situation at the given moment, and by a study of the mistakes that have been committed in this sphere.[28]"

The role of the national question in the Soviet Union has been a source of a disagreement between Lenin and Stalin following the "Georgian Affair" in 1922. This has triggered the discussion on the "national deviations" (natsionalnyi uklon) of the communist party leadership (who in this case were referred as uklonisty) in non-Russian republics. There was also further tendency to derive the terms from the surname of the particular politicians that was considered an uklonist by the central government in Moscow, such as: "Sultangalievshchina" (rus. from Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev),[29] "Shumskizm" (rus. from Alexander Shumsky), "Volobuevshchina “ (from Mykhailo Volobuiev), „Skripnikovshchina “ (rus. from Mykola Skrypnyk), "Khvylevizm“ (rus. from Mykola Khvylovy).

According to the letter written by Stalin to Lenin in 1922 his goal was the "replacement of fictitious independence by real internal autonomy of the republics in the sense of language, culture, justice, indoctrination, agriculture".[30]

The discussion on Ukrainian culture is mainly known in the context of discussion about Mykola Khvylovy, who suggested that Ukrainian literature should be looking more towards Europe than towards Russia. As a reaction to the literature discussions organised by Khvylovy, Joseph Stalin has written the following in a letter to Kaganovich in 1926 : "Commrade Shumsky fails to see that, given the weakness of the indigenous communist cadres in Ukraine, this movement, led by a number of non-communist intellectuals, can in some places take on the character of a struggle for the alienation of Ukr. culture and public from the culture and public of the All-Soviet Union, the character of a struggle against "Moscow" in general, against Russians in general, against Russian culture and its highest achievement - against Leninism. I shall not prove that such a danger is becoming more and more real in Ukraine. I would only say that even some Ukrainian communists are not free from such defects".[31]

The Kommunist magazine summarised the following on the basis of Stalin's published letter in the same year: "Zoological Russophobia, of which the articles by Khvylovy "Away from Moscow" and others, criticised by Mr. Skrypnyk in No. 1 of the "Ukrainian Bolshevik" 1926, are examples that does not exist only in literature. In part it is an uncritical transfer to the Russian people of the hatred which Russian tsarism aroused on the part of the oppressed nations. But to a much greater extent, its cultivation is a deliberate means on the part of the covert counter-revolutionary elements to weaken the Soviet power by isolating the individual peoples of the USSR as hostile as possible [..]. And in fact and objectively the matter boils down to subversive work against the Soviet system as a whole, with the choice of the least protected place for this work. In such young states as, for example, Ukraine, the very composition of the state apparatus servicing cultural work is inevitably recruited to a certain extent from members of the former bourgeois nationalist chauvinist parties, from persons who at one time sympathised with the Petliurovtsy (from Symon Petliura), and so on. This, understandably, facilitates the appearance of corresponding perversions".[32]

The local soviet propaganda materials were mentioning petliurovshchina (from Symon Petliura) and makhnovshchina (from Nestor Makhno) as things to be eradicated as a part of fighting counter-revolutionary movement.

One other example of the propaganda against "national deviations" is the speech by Panas Lyubchenko at the Joint Plenum of the Central Committee (central government) and the Central Committee of the CP(B)U (Ukrainian Communist Party) titled "Fire on the nationalist counter-revolution and on nationalist deviators"[33] on 22 of November 1933. In 1937 Panas Lyubchenko committed suicide after he was accused of allegedly having connections to Ukrainian nationalists.[34]

Ukrainians in the Soviet Ukraine and in RFSSR

[edit]

According to the Soviet census 1926 many Ukrainians lived outside of Ukrainian SSR, including other regions affected by the famine.

On December 15, 1932, the decision to immediately stop Ukrainization in the USSR in Ukrainian districts of the regions such as in the Far Eastern Krai, Kazakhstan, Central Asia, Central Black Earth Region and others was made. It was demanded to transfer all Ukrainianised newspapers, press and publications into Russian and by the autumn of 1933 prepare the transition of schools and teaching to Russian language.[35]

The All-Union census of 1926 showed that 23,218,860 ethnic Ukrainians, 92,078 Bulgarians, 1,574,39 Jews, 3,939,24 Germans, 476,435 Poles, and others lived in the Ukrainian SSR.[36]

The total number of Ukrainians in USSR constituted 31,194,976 persons, which means that 7,976,116 Ukrainians lived in the Soviet Union outside of Ukrainian SSR as per Soviet census 1926 (3,106,852 in North Caucasus Krai ; 1,651,853 in Central Black Earth Region, 860,822 in Kazakh ARSR, 827,536 in Siberian Krai, 440, 225 in Lower Volga region, etc.).

Many were forcefully deported, particularly during the period of 1930s and later, and died due to not being provided with appropriate conditions in the new settlements.

Ukrainian SSR has undergone multiple administrative and territorial changes during the time of Holodomor making tracking individual localities particularly difficult.

Targeting Soviet Ukraine

[edit]Although famine, allegedly caused by collectivization, raged in many parts of the Soviet Union in 1932, special and particularly lethal policies, according to Yale historian Timothy Snyder in his book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (2010), were adopted in and largely limited to Ukraine at the end of 1932 and 1933.[37] Snyder lists seven crucial policies that applied only, or mainly, to Soviet Ukraine. He states: "Each of them may seem like an anodyne administrative measure, and each of them was certainly presented as such at the time, and yet each had to kill."[38] Among them are:[37]

- From 18 November 1932, peasants from Ukraine were required to return extra grain they had previously earned for meeting their targets. State police and party brigades were sent into these regions to root out any food they could find.

- Two days later, a law was passed forcing peasants who could not meet their grain quotas to surrender any livestock they had.

- Eight days later, collective farms that failed to meet their quotas were placed on "blacklists" in which they were forced to surrender 15 times their quota. These farms were picked apart for any possible food by party activists. Blacklisted communes had no right to trade or to receive deliveries of any kind, and became death zones.

- On 5 December 1932, Stalin's security chief presented the justification for terrorizing Ukrainian party officials to collect the grain. It was considered treason if anyone refused to do their part in grain requisitions for the state.

- In November 1932, Ukraine was required to provide one third of the grain collection of the entire Soviet Union. As Lazar Kaganovich put it, the Soviet state would fight "ferociously" to fulfill the plan.

- In January 1933, Ukraine's borders were sealed in order to prevent Ukrainian peasants from fleeing to other republics. By the end of February 1933, approximately 190,000 Ukrainian peasants had been caught trying to flee Ukraine and were forced to return to their villages to starve.

- The collection of grain continued even after the annual requisition target for 1932 was met in late January 1933.[37]

Ethnic discrimination

[edit]According to some scholars, collectivization in the Soviet Union and other Soviet policies were primary contributors to famine mortality (52% of excess deaths), and some evidence shows there was discrimination against ethnic Ukrainians and Germans.[39] According to a Centre for Economic Policy Research paper published in 2021 by Andrei Markevich, Natalya Naumenko, and Nancy Qian, regions with higher Ukrainian population shares were struck harder with centrally planned policies corresponding to famine such as increased procurement rate,[40] and Ukrainian populated areas were given lower amounts of tractors which the paper argues demonstrates that ethnic discrimination across the board was centrally planned, ultimately concluding that 92% of famine deaths in Ukraine alone along with 77% of famine deaths in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus combined can be explained by systematic bias against Ukrainians.[41]

According to Mark Tauger,[42] "if the regime had not taken even that smaller amount grain from Ukrainian villages, the famine could have been greatly reduced or even eliminated" however (in his words) "if the regime had left that grain in Ukraine, then other parts of the USSR would have been even more deprived of food than they were, including Ukrainian cities and industrial sites, and the overall effect would still have been a major famine, even worse in “non-Ukrainian” regions."[42] In fact in contrast to Naumenko's paper's claims the higher Ukrainian collectivization rates in Tauger's opinion actually indicate a pro-Ukrainian bias in Soviet policies rather than an anti-Ukrainian one: "[Soviet authorities] did not see collectivization as “discrimination” against Ukrainians; they saw it as a reflection of—in the leaders’ view—Ukraine's relatively more advanced farming skills that made Ukraine better prepared for collectivization (Davies 1980a, 166, 187–188; Tauger 2006a)."[42]

Naumenko responded to some of Tauger's criticisms in another paper.[43] Naumenko criticizes Tauger's view of the efficacy of collective farms arguing Tauger's view goes against the consensus,[43] she also states that the tenfold difference in death toll between the 1932-1933 Soviet famine and the Russian famine of 1891–1892 can only be explained by government policies,[43] and that the infestations of pests and plant disease suggested by Tauger as a cause of the famine must also correspond such infestations to rates of collectivization due to deaths by area corresponding to this[43] due Naumenko's findings that: "on average, if you compare two regions with similar pre-famine characteristics, one with zero collectivization rate and another with a 100 percent collectivization rate, the more collectivized region’s 1933 mortality rate increases by 58 per thousand relative to its 1927–1928 mortality rate".[43] Naumenko believes the disagreement between her and Tauger is due to a "gulf in training and methods between quantitative fields like political science and economics and qualitative fields like history" noting that Tauger makes no comments on one of her paper's results section.[43]

Requisition quotas

[edit]

In the summer of 1930, the Soviet government had instituted a programme of food requisitioning, ostensibly to increase grain exports. The same year Ukraine produced 27% of the Soviet harvest but provided 38% of the deliveries, and in 1931 it made 42% of the deliveries. Yet the Ukrainian harvest fell from 23.9 million tons to 18.3 million tons in 1931, but the previous year's quota of 7.7 million tons remained. Authorities were able to procure only 7.2 million tons, and in 1932 just 4.3 million tons of a reduced quota of 6.6 million tons.[44] Between January and mid April 1933 a factor contributing to a surge of deaths within certain region of Ukraine during the period was the relentless search for "hidden grain" by the confiscation of all food stuffs from certain households, which Joseph Stalin implicitly approved of through a telegram he sent on 1 January 1933 to the Ukrainian government reminding Ukrainian farmers of the severe penalties for not surrendering grain they may be hiding.[20] In his review of Anne Applebaum's book Mark Tauger gives a rough estimate of those affected by the search for hidden grain reserves: "In chapter 10 Applebaum describes the harsh searches that local personnel, often Ukrainian, imposed on villages, based on a Ukrainian memoir collection (222), and she presents many vivid anecdotes. Still she never explains how many people these actions affected. She cites a Ukrainian decree from November 1932 calling for 1100 brigades to be formed (229). If each of these 1100 brigades searched 100 households, and a peasant household had five people, then they took food from 550,000 people, out of 20 million, or about 2-3 percent."[45]

Confiscation of grain reserve funds

[edit]In order to make up for unfulfilled grain procurement quotas in Ukraine, reserves of grain were confiscated from three sources including, according to Oleh Wolowyna, "(a) grain set side for seed for the next harvest; (b) a grain fund for emergencies; (c) grain issued to collective farmers for previously completed work, which had to be returned if the collective farm did not fulfill its quota."[20]

Torgsin system

[edit]Torsion networks appeared in 1931.They were selling goods for foreign currency or exchanging them for precious metals. Originally only exclusively for foreigners, but later soviet citizens were also allowed to exchange the goods. During Holodomor people brought family heritage - crosses, earrings, wedding rings to Torgsins and exchanged it for special stamps, for which they could obtain basic goods - mostly flour, cereals or sugar. Torgsins operated at highly speculative prices and were known for long queues. With that mechanism authorities were able to extort from the population whatever could have been hidden during the confiscations. Many families survived, in particular thanks to Torgsin.[46] Yet the network was also a cause of a psychological trauma,[47] since people had to give up on family valuables and relics that had not only material, but also spiritual value. During the Holodomor, the network of torgsins expanded considerably—by the end of 1933, there were already about 300 such shops in Soviet Ukraine.[47] In 1933, the population brought 45 tons of pure gold to torsgins. The network existed until 1936 .

Criminalization of gleaning

[edit]Gleaning is the act of collecting leftover crops from farmers' fields after they have been commercially harvested or from fields where it is not economically profitable to harvest. Some ancient cultures promoted gleaning as an early form of a welfare system. In the Soviet Union, people who gleaned and distributed food brought themselves under legal risk. The Law of Spikelets criminalised gleaning under penalty of death, or ten years of forced labour in exceptional circumstances.[citation needed]

Some sources say there were several legislative acts adopted in order to force starvation in the Ukrainian SSR. On 7 August 1932, the Soviet government passed a law, "On the Safekeeping of Socialist Property",[48] that imposed penalties starting at a ten-year prison sentence and up to the death penalty for any theft of socialist property.[49][50][51] Stalin personally appended the stipulation: "People who encroach on socialist property should be considered enemies of the people."[52] Within the first five months of passage of the law, 54,645 individuals had been imprisoned under it, and 2,110 sentenced to death. The initial wording of the decree, "On fought with speculation", adopted 22 August 1932, led to common situations where minor acts such as bartering tobacco for bread were documented as punished by 5 years imprisonment. After 1934, by NKVD demand, the penalty for minor offenses was limited to a fine of 500 roubles or three months of correctional labour.[53]

The scope of this law, colloquially dubbed the "law of the wheat ears",[48] included even the smallest appropriation of grain by peasants for personal use. A little over a month later, the law was revised, as Politburo protocols revealed that secret decisions had later modified the original decree of 16 September 1932. The Politburo approved a measure that specifically exempted small-scale theft of socialist property from the death penalty, declaring that "organizations and groupings destroying state, social, and co-operate property in an organized manner by fires, explosions and mass destruction of property shall be sentenced to execution without trial", and listed a number of cases in which "kulaks, former traders, and other socially-alien persons" would be subject to the death penalty. "Working individual peasants and collective farmers" who stole kolkhoz property and grain would be sentenced to ten years; the death penalty would be imposed only for "systematic theft of grain, sugar beets, animals, etc."[54]

Soviet expectations for the 1932 grain crop were high because of Ukraine's bumper crop the previous year, which Soviet authorities believed were sustainable. When it became clear that the 1932 grain deliveries were not going to meet the expectations of the government, the decreased agricultural output was first blamed on the kulaks, and later on agents and spies of foreign intelligence services, "nationalists", "Petlurovites", and from 1937 on, Trotskyists. According to a report from the head of the Supreme Court, by 15 January 1933 as many as 103,000 people (more than 14 thousand in the Ukrainian SSR) had been sentenced under the provisions of the 7 August decree. Of the 79,000 whose sentences were known to the Supreme Court, 4,880 had been sentenced to death, 26,086 to ten years of imprisonment, and 48,094 to other punishments.[54]

On 8 November, Molotov and Stalin issued an order stating, "from today the dispatch of goods for the villages of all regions of Ukraine shall cease until kolkhozy and individual peasants begin to honestly and conscientiously fulfill their duty to the working class and the Red Army by delivering grain."[55] On 24 November, the Politburo ordered that all those sentenced to confinement of three years or more in Ukraine be deported to labour camps. It also simplified procedures for confirming death sentences in Ukraine. The Politburo also dispatched Balytsky to Ukraine for six months with the full powers of the OGPU.[56]

Blacklist system

[edit]

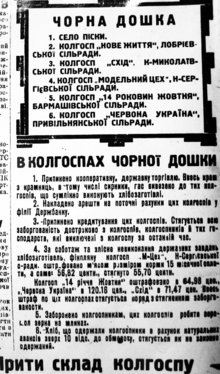

In certain collective farms, villages, and raions (districts) the Soviets imposed a blacklist regime (the chorna doshka or "black board") consisting of economic sanctions and a blockade by OGPU units which led to complete extermination by starvation in many of them. This was formalized in 1932 by the 20 November decree "The Struggle against Kurkul Influence in Collective Farms".[57] The blacklist was applied with harsher methods to selected villages and kolkhozes that were considered to be "underperforming" in the grain collection procurement: "Immediate cessation of delivery of goods, complete suspension of cooperative and state trade in the villages, and removal of all available goods from cooperative and state stores. Full prohibition of collective farm trade for both collective farms and collective farmers, and for private farmers. Cessation of any sort of credit and demand for early repayment of credit and other financial obligations."[58][59] Initially, such sanctions were applied to only six villages, but later they were applied to numerous rural settlements and districts. For peasants, who were not kolkhoz members and who were "underperforming" in the grain collection procurement, special measures were adopted. To reach the grain procurement quota amongst peasants, 1,100 brigades were organized, which consisted of activists, often from neighbouring villages, who had either already accomplished their grain procurement quota or were close to accomplishing it. In the end at least 400 collective farms were put on the "black board", more than half of them in Dnepropetrovsk alone.[60]

Since most of the goods supplied to the rural areas were commercial (fabrics, matches, fuels) and sometimes obtained by villagers from neighbouring cities or railway stations, sanctioned villages remained thus for a long period—as an example mentioned in the 6 December decree, the village of Kamyani Potoky was removed from blacklist on 17 October 1933, when they completed their plan for grain collection early. After January 1933, the blacklist regime was modified, with 100% plan execution no longer required. As mentioned in the 6 December Decree, the villages Liutenky and Havrylivka were removed from the black list after 88% and 70% plan completion, respectively.[61]

Measures were taken to persecute those withholding or bargaining grain. This was done frequently by requisition detachments, which raided farms to collect grain, and regardless of whether or not the peasants retained enough grain to feed themselves or enough seed left to plant the next harvest.[citation needed] In the end 37 out of 392 districts[62] along with at least 400 collective farms where put on the "black board" in Ukraine, more than half of the blacklisted farms being in Dnepropetrovsk Oblast alone.[63] Every single raion in Dnipropetrovsk had at least one blacklisted village, and in Vinnytsia oblast five entire raions were blacklisted.[57] This oblast is situated right in the middle of traditional lands of the Zaporizhian Cossacks. Cossack villages were also blacklisted in the Volga and Kuban regions of Russia.[57] In 1932, 32 (out of less than 200) districts in Kazakhstan that did not meet grain production quotas were blacklisted.[64] Some blacklisted areas[62] in Kharkov could have death rates exceeding 40%[65] while in other areas such as Vinnytsia blacklisting had no particular effect on mortality.[65] The only blacklisted district in the Stalino oblast[62] had a mortality rate that was roughly 2 to 3 times higher than most of the oblast with only 2 districts in the oblast having a comparable death rate.[65]

Restrictions on freedom of movement

[edit]Some sources[who?] state that Ukrainian SSR borders were sealed by the NKVD and the army in order to prevent starving peasants from travelling into territories where food was more available. Some researchers believe these measures extended to urban areas inside Ukrainian SSR. During the first five-year plan, urban population growth brought more than 10 million people from villages to cities; the number receiving food rations increased from 25 million in 1930 to 40 million in 1932. Food production declined and urban food supplies fell drastically. Reserves did not keep pace with ration requirements. Desertion of factories, combined with peasants' flight from collective farms, resulted in millions of people moving around the country. In response, the government revived the tsarist institution of internal passports at the end of 1932[66]

The government introduced new identity papers and obligatory registration for citizens in December 1932.[67] Initially, the area of new identity papers and obligatory registration implementation was limited to Moscow, Leningrad (encircling 100 km), and Kharkov (encircling 50 km), and the new measures were planned for implementation by June 1933. In Ukraine, introduction of the passport system was to be carried out by the end of 1933, with top priority given to its enforcement in Kharkov, Kiev, and Odessa.[68]

New passports were issued only to urban residents, employees of state institutions, and workers of state farms in villages. The absence of passports during the Holodomor doomed millions of peasants to starvation, since it made them unable to travel outside of their settlements. It also restricted the freedom of movement for workers. Anyone who wanted to go to another area to work had to register with the housing office at the place of arrival within 24 hours of arrival. The first violation was punishable by a fine of 100 rubles, the second one - by imprisonment for up to 3 years. A 30-kilometer zone was introduced around Kharkiv (and since January 1934, after the capital was moved to Kyiv, around Kyiv), within which "socially dangerous elements" such as political exiles or former prisoners were prohibited from living.[69]

Special barricades were set up by GPU units throughout the Soviet Union to prevent an exodus of peasants from hunger-stricken regions. During a single month in 1933, 219,460 people were either intercepted and escorted back or arrested and sentenced.[67] In Ukraine, these measures had the following results, according to the declassified documents:[70][71][72][73]

During the 11 days (23 January – 2 February) after the 22 January 1933 decree:

3,861 people were "intercepted and filtered", out of which 3,521 returned to the place of permanent residence, 340 arrested. Out of those arrested: kulaks, tverdosdatchiks [those not selling wheat at the set price] and those, who refused to return to the places of permanent residence are prepared to be sent into exile. The rest [people without documents and bandits] are being "checked and sorted out". 250 organizers and instigators of the escapes are "having their documents prepared to be sent into the concentration camps".[70] During the same period, there were 16,773 people intercepted (907 of those not living in Ukraine) in trains and at railway stations on the whole Ukrainian territory; out of those, 1,610 people were "arrested and handed over to GPU", 9 of those who refused to return to a place of the permanent residence are sent to "special settlements" (spetsposelenie) in Kazakhstan.[71]

In the same document, the GPU states that 94,433 peasants had already left the Ukrainian territory during the period from 15 December 1932 to 2 January 1933 (data for 215 districts out of 484, and Moldavian ASRR). It has been estimated that there were some 150,000 excess deaths as a result of this policy, and one historian asserts that these deaths constitute a crime against humanity.[74] In contrast historian Stephen Kotkin argues that the sealing of the Ukrainian borders caused by the internal passport system was in order to prevent the spread of famine related diseases.[75]

Travel from Ukraine and the Northern Caucasus Kuban kray region was specifically forbidden by the directives of 22 January 1933 (signed by Molotov and Stalin) and of 23 January 1933 (joint directive Central Committee of the Communist Party and Sovnarkom). 16 February 1933, the same measures were applied to the Lower-Volga region.[76] After February, the directives stated that travel "for bread" from these areas was organized by enemies of the Soviet Union, with the purpose of agitation in northern areas of the Soviet Union against kolkhozes, but was not prevented. Therefore, railway tickets were to be sold only by ispolkom permits, and those who had already reached the north should be arrested.[77]

GPU repressions in search for Nationalists Organisations

[edit]According to the Russian archives in 1933 GPU was conducting the liquidation of the Ukrainian Military Organization (predecessor of OUN) [78] in parallel to also targeting Polish Military Organization in Ukraine. The accusation documents for both were reportedly fabricated.[79]

Ukrainian resistance movement

[edit]Ukrainians have actively resisted soviet policies. During 1928–1930, the GPU of the Ukrainian SSR repeatedly informed the OGPU and the party leadership about dangerous trends in Ukrainian villages that could lead to the collapse of the Soviet system. One of the most known protest being Pavlohrad uprising in 1930.[80]

The information about the Soviet terror in the Soviet Ukraine contained in the protest of Ukrainian Section of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom to Leagues of Nations in September 1930: "against the terror in Soviet Ukraine, in particular against the political, economic and religious persecutions against the mass arrests of scholars, student youth and the nationally-minded population of Soviet Ukraine, as well as against the continuing persecution of the Ukrainian population in all other Ukrainian territories under foreign rule [Poland is mentioned as an example] [81]"

Information blockade

[edit]The Soviet regime, by preventing news of the famine from reaching the outside world, prevented foreign sources from providing aid to alleviate the famine and associated hardships. For example, Mark Tauger states that: "the biggest mistake of the regime in this period (1932-1933) was to turn down the many offers of food imports from other countries, which they had previously accepted in the famines of 1921–23, 1924–25, and 1928–29."[42]

Some say the same thing happened during the earlier 1921–23 famine in the Soviet Union. With regard to the earlier famine, some researchers comments that initial Soviet pleas for aid in early autumn 1921 were refused by European countries, and what aid was eventually provided did not come for four or five months, so the Soviet government may not have expected the outside world to be very helpful in this instance either.[citation needed]

Yet, according to James Abbe in his "I Photograph Russia" published in 1934 a few foreign photographers, including himself, were invite to the produce the pictures, which should show that no hunger was happening. In the chapter "Banquets and Famine" he describe taking photographs in eastern Ukraine as follows: "We picked out types and subjects for the camera from the better nourished portions, made a swell hundred feet or so of beautifully build miners […]. By concentrating on the better-looking girls […] we got a shot which made the daily grind […] look like joyous labor of a triumphant proletariat […]. It was not shown on the films that these girls and most mine workers were straining at muscular tasks on inadequately filled stomachs. I took many other photos but our official guides would not sanction the filming of the series of banquets we attended all through the coal regions, for our films were to be projected in Russia and might show the natives that somebody was getting enough to eat. During the ten days we spent in the mining district it was impossible to sit down to a meal without facing a table groaning with caviar, roast turkey, chicken, cold fish of every description, pastries, even the rarest of all luxuries: tenderloin steak”.[82]

May 27, 1932 first note in the German newspaper "Vossische Zeitung" titled "Hunger in Russian Granary" and four days later in French "Le Temps", confirming the information about hunger as well as it was "organised".[83]

7 June 1932 a report on mass hunger was published in Austrian «Das Neue Wiener Journal».[83]

On 23 February 1933, the Politburo of Central Committee adopted a decree requiring foreign journalists to seek travel permits from the General Directorate of Militia before entering the affected areas. Also, the Soviet government denied initial reports of the famine but agreed with information about malnutrition, while preventing foreign journalists from travelling in the region. At the same time, there was no credible evidence of information blockade arrangements on a considerable number of foreign specialists, such as engineers, who worked at construction sites at Ukrainian territory.[citation needed]

For example, Gareth Jones, one of David Lloyd George's private secretaries, spent several days in mid-March travelling to "all twenty villages, not only in Ukraine, but also in the black earth district, and in the Moscow region, and ... I slept in peasants' cottages, and did not immediately leave for the next village."[citation needed] He reached the neighbouring rural area of Kharkov (the capital of Soviet Ukraine), spent some days there, and despite seeing no dead people or animals himself, reported "that there was famine in the Soviet Union."[citation needed]

Some foreigners, such as representatives of the countries that had diplomatic relationships with the Soviet Union, among them Poland, were able to provide information.

On 13 June 1933 Józefina Pisarczykówna, an official at the Polish consulate in Kharkiv, related that: "There are dying people and corpses in the streets. Cars full of policemen drive around the city and pick up anyone suspicious-looking or poor. They are taken to the barracks, where, it is said, the completely emaciated ones are given lethal injections". On June 22, 1933, Stanislaw Sosnicki, the Polish consul in Kyiv, provided the following information to the Division II: "over the past three weeks corpses have been collected with ever increasing frequency and speed".[84]

As of June1933 the information spread by the 'Protestant Aid Committee "Brüder in Not" in Berlin informed that "for more than 6 months we have been trying to alleviate the terrible need by transferring food and money. Only with the greatest of difficulties was it possible to obtain permission from the Russian authorities to provide aid at all. But even now, because of the prohibitive and constantly changing customs duties, no food parcels packed by private individuals can be sent to Russia, only so-called standard parcels packed in Russia itself by the State Trading Company [Torgsin]".[85] Later, in October 1933, in a response to a complain by a German engineer about the quality of German reporting on Soviet Union the Reich Chancellery has answered the follows: "[it needs to be understood ] that the Reich Government is probably much better informed about the situation in Russia than any other great power. We maintain one embassy and seven consulates in Russia, a number that places us well above all other foreign missions. A further source of information is made available to us by the numerous German engineers employed in Russia. Also, the numerous letters that have arrived in Germany because of the hunger catastrophe in South Russia [Ukraine] contained important communications. One can therefore assume that nothing of what goes on in Russia remains hidden to us".[86]

On July 25, 1933, French «Le Matin» wrote "At a time when the whole world is complaining about a crisis of overproduction, Russia is suffering from a terrible shortage. This shortage is even more substantial than in 1921. And its causes are not bad weather or drought, but solely the present regime. The results of its activities are appalling. Millions of people die every day from hunger, whole villages are emptied. All this is because on collective lands, ruled by ruthless bureaucrats, crops are organized very late or too poorly. [...]. For months now, in Ukraine, one can find only bread made of wood bark and indigestible waste products. [...] The seriousness of this catastrophe has concerned even the Soviet government. Moscow is unwilling and, most likely, unable to resolve the issue by implementing the prescribed measures [...]. So the government has decided [..] to punish vigorously the guilty and the innocent. If for any reason, for example, because of an outside invasion, this process is forced to be interrupted, Russia will find itself in such a catastrophic situation that an outside attack will be simply inevitable [87]".

On July 30, 1933, the New York Times published the following: "The National Democrats oppose any action that appears treacherous to the Poles, but greatly embarrassed the Polish Government by creating a special relief committee for 'starving brethren' in the Soviet Ukrainia in spite of Soviet denials of a famine. Many Soviet Ukrainians have crossed Polish borders searching for food. They say former Red Army soldiers from the North are settling along the frontier to combat anti-Sovet agitation led by the Berlin group".[88]

On 20 August 1933 The New York Times published the appeal by Archbishop of Vienna to provide help in Russian famine saying that "toll will be millions unless world heeds plea".[89] As his source for the information on the hunger as well as on official denying it he referenced the Metropolitan of Galicia, Andrey Sheptytsky.

On 23 August 1933, foreign correspondents were warned individually by the press section of the Foreign Office of the Soviet Union not to attempt to travel to the provinces or elsewhere in the Soviet Union without first obtaining formal permission. The Foreign Office of the Soviet Union, without explanation, refused permission to William H. Chamberlain, The Christian Science Monitor correspondent, to visit and observe the harvest in the principal agricultural regions of the North Caucasus and Ukraine. From May–July 1933, two other American correspondents were forbidden to make a trip to Ukraine.[90] Such restrictions were softened in September 1933.[citation needed]

On 21 October 1933 one of the OUN members, Mykola Lemyk, assassinated Aleksei Mailov, OGPU agent and Secretary of the Soviet Union's consulate in Lviv [Poland at that time]. The assassination was declared as a protest against soviet terror and the famine in Ukraine. It is argued that this became a rising point of Ukrainian support for OUN, particularly due to the weak international reaction to hunger.[91]

On November 18, 1933, around 10.000 Ukrainian Americans went on the streets to demand the denunciation of U.S. recognition of the USSR. The report that appeared in The New York Times featured the photo of the banner with the following wording: "We Condemn the Murderous Starvation of Ukraine by Soviet Government". Extensive reports have also appeared in the N.Y. Herald Tribune, The Sun, The New York Journal-American, Daily News and Sunday Mirror under the same date.[92]

Scholars who have conducted research in declassified archives have reported "the Politburo and regional Party committees insisted that immediate and decisive action be taken in response to the famine such that 'conscientious farmers' not suffer, while district Party committees were instructed to supply every child with milk and decreed that those who failed to mobilize resources to feed the hungry or denied hospitalization to famine victims be prosecuted."[93]

By the end of 1933, based on data collected by undercover investigation and photos, the Bohemian-Austrian Cardinal Theodor Innitzer began an awareness-raising campaign in the West about the massive deaths by hunger and occasional cases of cannibalism that were occurring in Ukraine and the North Caucasus at that time.[94]

A piece from the British Section of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom answer to Ukrainian appeals written August 1934 is worth mentioning here: "In general I know the Ukrainians are extremely wishful for the sympathy and support of women’s International organisations, but they say that the W.I.L.P.F. is so much influenced by its pro-communistic members that they are afraid it will not take a sympathetic view of their case, which is, of course, partly nationalist. They are extremely anxious that the conditions of famine should be made known and denounced and they are afraid that our French and German Soviet friends will not support them. Personally I should be in favour of bringing their report of famine conditions before our members as it is a concrete fact, which it is unfair to deny because to some it is politically inconvenient [95]"

On 18 September 1934 the Soviet government was elected a member of the League of Nations and accorded a permanent seat in the council.[96] According to researchers, "the pressure for good relations was being put on governments by businesses who saw the potential for trade and who preferred to believe that reports of famine were exaggerated" and thus, only 5 governments voted against the admission. They included Switzerland, which raised the issue of famine. Ireland, Germany, and Spain also voted in the League of Nations for immediate action.[91]

Refusal to provide aid

[edit]

Despite the pleas for assistance and the acknowledged famine situation, the Moscow authorities refused to provide aid. For example, Snyder writes that Stalin had privately admitted that while there was famine in Soviet Ukraine, he did not grant the Ukrainian party leadership's request for food aid.[38] Around 1,997,000 tons of grain was estimated by official Soviet figures by July 1, 1933, to have been concealed in two secret grain reserves for the Red Army and other groups with the actual figure being closer to roughly 1,141,000 which means in the opinion to a paper by Stephen Wheatcroft, Mark Tauger, and R.W. Davies that (in the paper's words): "it seems certain that, if Stalin had risked lower levels of these reserves in spring and summer 1933, hundreds of thousands-perhaps millions-of lives could have been saved".[16] that aid was provided only during the summer.[who?] The first reports regarding malnutrition and hunger in rural areas and towns (which were undersupplied through the recently introduced rationing system) to the Ukrainian GPU and oblast authorities are dated to mid-January 1933; however, the first food aid sent by Central Soviet authorities for the Odessa and Dnepropetrovsk regions 400 thousand poods (6,600 tonnes, 200 thousand poods or 3,300 tonnes for each) appeared as early as 7 February 1933.[97] Measures were introduced to localize these cases using locally available resources. While the numbers of such reports increased, the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine issued a decree on 8 February 1933, that urged every "hunger case" to be treated without delay and with a maximum mobilization of resources by kolkhozes, raions, towns, and oblasts. The decree set a seven-day term for food aid which was to be provided from "central sources". On 20 February 1933, the Dnepropetrovsk oblast received 1.2 million poods of food aid, Odessa received 800 thousand, and Kharkov received 300 thousand. The Kiev oblast was allocated 6 million poods by 18 March The Ukrainian authorities also provided aid, but it was limited by available resources. In order to assist orphaned children, the Ukrainian GPU and People's Commissariat for Health created a special commission, which established a network of kindergartens where children could get food. Urban areas affected by food shortage adhered to a rationing system. On 20 March 1933, Stalin signed a decree which lowered the monthly milling levy in Ukraine by 14 thousand tons, which was to be redistributed as an additional bread supply "for students, small towns and small enterprises in large cities and specially in Kiev." However, food aid distribution was not managed effectively and was poorly redistributed by regional and local authorities.[citation needed]

After the first wave of hunger in February and March, Ukrainian authorities met with a second wave of hunger and starvation in April and May, specifically in the Kiev and Kharkov oblasts. The situation was aggravated by the extended winter.[citation needed] Between February and June 1933, thirty-five Politburo decisions and Sovnarkom decrees authorized the issue of a total of 35.19 million poods (576,400 tonnes),[98] or more than half of total aid to Soviet agriculture as a whole. 1.1 million tonnes were provided by Central Soviet authorities in winter and spring 1933 — grain and seeds for Ukrainian SSR peasants, kolhozes and sovhozes. Such figures did not include grain and flour aid provided for the urban population and children, or aid from local sources. In Russia, Stalin personally authorized distribution of aid in answer to a request by Sholokhov, whose own district was stricken.[99] However, Stalin also later reprimanded Sholokhov for failing to recognize "sabotage" within his district. This was the only instance that a specific amount of aid was given to a specific district.[99] Other appeals were not successful, and many desperate pleas were cut back or rejected.[100]

Documents from Soviet archives indicate that the aid distribution was made selectively to the most affected areas, and during the spring months, such assistance was the goal of the relief effort. A special resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine for the Kiev Oblast, from 31 March 1933, ordered peasants to be hospitalized with either ailing or recovering patients. The resolution ordered improved nutrition within the limits of available resources so that they could be sent out into the fields to sow the new crop as soon as possible.[101] The food was dispensed according to special resolutions from government bodies, and additional food was given in the field where the laborers worked.[citation needed]

The last CPSU Politburo decision about food aid to the whole of the Ukrainian SSR was issued on 13 June 1933. Separate orders about food aid for regions of Ukraine appeared by the end of June through early July 1933 for the Dnepropetrovsk, Vinnitsia and Kiev regions. For the kolkhozes of the Kharkiv region, assistance was provided by end of July 1933 (Politburo decision dated 20 July 1933).[102]

What aid was given was selectively distributed to preserve the collective farm system. Grain producing oblasts in Ukraine such as Dnipropetrovsk were given more aid at an earlier time than more severely affected regions like Kharkov which produced less grain.[20] Joseph Stalin had quoted Vladimir Lenin during the famine declaring: "He who does not work, neither shall he eat."[103] This perspective is argued by Michael Ellman to have influenced official policy during the famine, with those deemed to be idlers being disfavored in aid distribution as compared to those deemed "conscientiously working collective farmers";[103] in this vein, Olga Andriewsky states that Soviet archives indicate that the most productive workers were prioritized for receiving food aid.[104] Food rationing in Ukraine was determined by city categories (where one lived, with capitals and industrial centers being given preferential distribution), occupational categories (with industrial and railroad workers being prioritized over blue collar workers and intelligentsia), status in the family unit (with employed persons being entitled to higher rations than dependents and the elderly), and type of workplace in relation to industrialization (with those who worked in industrial endeavors near steel mills being preferred in distribution over those who worked in rural areas or in food).[105]

Export of grain and other food despite world wheat surplus

[edit]After recognition of the famine situation in Ukraine during the drought and poor harvests, the Soviet government in Moscow continued to export grain rather than retain its crop to feed the people,[106] though at a lower rate than in previous years.[107] In 1930–31, there had been 5,832,000 metric tons of grains exported. In 1931–1932, grain exports declined to 4,786,000 metric tons. In 1932–1933, grain exports were just 1,607,000 metric tons, and in 1933–34, this further declined to 1,441,000 metric tons.[108] Officially published data[109] differed slightly:

- Cereals (in tonnes)

- 1930 – 4,846,024

- 1931 – 5,182,835

- 1932 – 1,819,114 (~750,000 during the first half of 1932; from late April ~157,000 tonnes of grain was also imported)

- 1933 – 1,771,364 (~220,000 during the first half of 1933;[110] from late March grain was also imported)[111]

- Only wheat (in tonnes)

- 1930 – 2,530,953

- 1931 – 2,498,958

- 1932 – 550,917

- 1933 – 748,248

In 1932, via Ukrainian commercial ports the following amounts were exported: 988,300 tons of grains and 16,500 tons of other types of cereals. In 1933, the totals were: 809,600 tons of grains, 2,600 tons of other cereals, 3,500 tons of meat, 400 tons of butter, and 2,500 tons of fish. Those same ports imported the following amounts: less than 67,200 tons of grains and cereals in 1932, and 8,600 tons of grains in 1933.[citation needed] The following amounts were received from other Soviet ports: in 1932, 164,000 tons of grains, 7,300 tons of other cereals, 31,500 tons of [clarification needed], and no more than 177,000 tons of meat and butter; in 1933, 230,000 tons of grains, 15,300 tons if other cereals, 100 tons of meat, 900 tons of butter, and 34,300 tons of fish.[citation needed] Michael Ellman states that the 1932–1933 grain exports amounted to 1.8 million tonnes, which would have been enough to feed 5 million people for one year.[74]

Particularly important is to understand that Holomodor happened in the background of the Wheat Agreement of 1933, signed in London by all major producers of the world's grain supplies. During the period of 1926-1934 the world producers actually grew more wheat than people consumed, resulting in significant surpluses that drove the price down. By the end of 1930, the price of wheat had dropped to a new low and the surplus was the problem.[112]

Colonialism or Imperialism

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2023) |

Other sources discuss the famine in relation to a project of imperialism or colonialism of Ukraine by the Soviet state.[113][114][115][116]

Destruction of Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

[edit]Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC) considers a successor of the Metropolis of Kyiv and all Rus which existed under the Ecumenical Patriarchate until 1686 (when it was incorporated into the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church). The re-establishment Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church began in 1917 during the dissolution of the Russian Empire as part of the Ukrainian independence movement. The church was proclaimed in 1921.[117] Although the UAOC was not a canonically recognised hierarchy, yet, in 1924 the decision by which the establishment of the Polish Autocephalous Orthodox Church was proclaimed by Ecumenical Patriarchat of Constantinople, has also recognised the of incorporating the Kyivan Metropolita into the Russian Orthodox Church as invalid.[118]

Coiner of the term genocide, Raphael Lemkin considered the repression of the Orthodox Church to be a prong of genocide against Ukrainians when seen in correlation to the Holodomor famine.[119] Collectivization did not just entail the acquisition of land from farmers but also the closing of churches, burning of icons, and the arrests of priests.[120] Associating the church with the tsarist regime,[121] the Soviet state continued to undermine the church through expropriations and repression.[122] They cut off state financial support to the church and secularized church schools.[121] According to Lemkin, between 1926 and 1932, the Ukrainian Orthodox Autocephalous Church, its Metropolitan (Vasyl Lypkivsky) and 10,000 clergy were liquidated.[123] By early 1930 75% of the Autocephalist parishes in Ukraine were persecuted by Soviet authorities.[124] The GPU instigated a show trial which denounced the Orthodox Church in Ukraine as a "nationalist, political, counter-revolutionary organization" and instigated a staged "self-dissolution."[124]

In December 1930 the church was allowed to reorganize under a pro-Soviet cosmopolitan leader of Ivan Pavlovskyi, receiving a new name - "Ukrainian Orthodox Church". The new church had dissociate itself formally from the three principles of UAOC: autocephaly, Ukrainianization and conciliar self-government, as well as to commit its members to Soviet patriotism and an unconditional loyalty to the regime.[124] By 1936 the last parish of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church was suppressed, remaining bishops imrisoned, including Pavlovskyi.[124] During the 1935-1937 many churches were physical destructed, including the St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery.

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Church was re-established for the third time on 22 October 1989, right before the fall of the Soviet Union and was recognised by Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in 2018 after the merge with Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kyiv Patriarchate, which was created in 1992. Moscow Patriarchate continues to opposes the recognition.

Elimination of Ukrainian cultural elite

[edit]Changes in cultural politics also occurred. An early example was the 1930 show trial of the "Union for the Freedom of Ukraine" at which 45 intellectuals, higher education professors, writers, a theologian and a priest were publicly prosecuted in Kharkiv, then capital of Soviet Ukraine. Fifteen of the accused were executed, many more with links to the defendants (248) were sent to the camps. (This was one of a series of contemporary show trials, held in the North Caucasus, 1929 in Shakhty, and in Moscow, the 1930 Industrial Party Trial and the 1931 Menshevik Trial.) The total number is not known, but tens of thousands[125] of people are estimated to have been arrested, exiled, and/or executed during and after the trial including 30,000[126] intellectuals, writers, teachers, and scientists. In this vein the secretary of the Kharkiv Oblast referred to "bourgeois-nationalistic rabble" as "class enemies" near the end of the famine.[127]

In Ukraine there was a widespread purge of communist party officials at all levels. According to Oleh Wolowyna 390 "anti-Soviet, counter-revolutionary insurgent and chauvinist" groups were eliminated resulting in 37,797 arrests, that lead to 719 executions, 8,003 people being sent to Gulag camps, and 2,728 being put into internal exile.[20] 120,000 individuals in Ukraine were reviewed in the first 10 months of 1933 in a top to bottom purge of the communist party resulting in 23% being eliminated as "class hostile" elements.[20] Pavel Postyshev was set in charge of placing people in the head of Machine-Tractor Stations in Ukraine which were responsible for purging "class hostile elements."[20] By the end of 1933 60% of the heads of village councils and raion committees in Ukraine were replaced with an additional 40,000 lower tier workers being purged.[20]

By the end of the 1930s, approximately four-fifths of the Ukrainian cultural elite had been eliminated.[128] Some, like Ukrainian writer Mykola Khvylovy, committed suicide. One of the leading Ukrainian Bolsheviks, Mykola Skrypnyk, who was in charge of the decade-long Ukrainization program that had been decisively brought to an end, shot himself in the summer of 1933 at the height of the purge of the CP(b)U. Whole academic organizations, such as the Bahaliy Institute of History and Culture, were shut down following the arrests.[citation needed] Repression of the intelligentsia occurred in virtually all parts of the Soviet Union.[129] Despite the assault, education and publishing in the republic remained Ukrainianized for years afterward. In 1935–36, 83% of all school children in the Ukrainian SSR were taught in Ukrainian, with Ukrainians making up about 80% of the population.[130] In 1936, of 1830 newspapers, 1402 were in Ukrainian, as were 177 magazines, and in 1936, 69 thousand Ukrainian books were printed.[131]

The recent award-winning documentary Genocide Revealed (2011),[132] by Canadian-Ukrainian director Yurij Luhovy, presents evidence for the view that Stalin and his cohorts in the Communist regime (not necessarily the Russian people as a whole) deliberately targeted Ukrainians in the mass starvation of 1932–1933. Stalin's regime proceeded to eliminate the intelligentsia of Ukraine[citation needed], to forcibly deport Ukrainian Kulaks who opposed its collectivization policies, and to orchestrate a deliberate mass starvation by hunger of Ukrainians, wherever they were found throughout the Soviet Empire.[133] This documentary reinforces the view that the Holodomor was indeed an act of genocide.[citation needed]

Changing Ukrainian language

[edit]Since 1925 the commission of Ukrainian academics has been working to create a unified All-Ukrainian orthography, by carefully considering representative from different lands - including the territories of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic, that became a part of Poland following Paris Peace Conference. By 1926 the draft was provided and later the Ukrainian orthography of 1928 (also known as "Skrypnykivka" by the name of Mykola Skrypnyk) was adopted. The orthography was printed and distributed in 1929 - since then all schools and publishing houses of the Ukrainian SSR were obliged to adhere to it. For the sake of the unity of the Ukrainian literary language, the leadership of the Shevchenko Scientific Society in Lviv decided to adhere to the norms of the new spelling in Galicia.

All further changes in the Ukrainian orthography were developed on behalf of the government by specially created orthographic commissions. In 1933, an orthography commission headed by A. Khvylia (Olinter), which was eliminated by the Stalinist regime in 1938, reworked the Ukrainian Spelling, recognizing the norms of 1927–1928 as "nationalist." On October 4, 1937, a critical article appeared in the newspaper Pravda, according to which the Ukrainian language should be brought closer to Russian.

Repressions against Ukrainian traditional musicians

[edit]Bandura is a traditional Ukrainian musical instrument, whereas bandurists were the carriers of traditional songs and folklore. One of the communist newspapers in 1930 already stated that "being in love with nationalist romance is not a communist thing" and in December 1933 during the All-Ukrainian Union of Art Workers, the bandura and kobza were declared class-enemy instruments,[134] which lead to the beginning of the repressions against the musicians playing them.

Repressions for collecting memories of Holodomor

[edit]NKVD has been systematically [135] punishing for attempt to preserve the memories about Holodomor. Records were confiscated and destroyed as "such that are of no value", where are as the owners of the records were sent to GULAG. An example of conviction for possession of memoirs on the Holodomor:

"being hostile to the Soviet authorities in the period 1930-1933, [...] wrote a diary of counter-revolutionary content, in which she condemned the actions of the Communist Party in organising collective farms in the USSR and described the difficult material conditions of workers".[136]

Consequence of collectivization

[edit]While a complex task, it is possible to group some of the causes that contributed to the Holodomor. They have to be understood in the larger context of Stalin's "social revolution from above" that took place in the Soviet Union at the time.[137]

Agrotechnological failures

[edit]Historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft lists four problems Soviet authorities ignored that would hinder the advancement of agricultural technology and ultimately contributed to the famine:[17]

- "Over-extension of the sown area" — Crops yields were reduced and likely some plant disease caused by the planting of future harvests across a wider area of land without rejuvenating soil leading to the reduction of fallow land.

- "Decline in draught power" — the over extraction of grain lead to the loss of food for farm animals, which in turn reduced the effectiveness of agricultural operations.

- "Quality of cultivation" — the planting and extracting of the harvest, along with ploughing was done in a poor manner due to inexperienced and demoralized workers and the aforementioned lack of draught power.

- "The poor weather" — drought and other poor weather conditions were largely ignored by Soviet authorities who gambled on good weather and believed agricultural difficulties would be overcome.

Collectivization

[edit]Approaches to changing from individual farming to a collective type of agricultural production had existed since 1917, but for various reasons (lack of agricultural equipment, agronomy resources, etc.) were not implemented widely until 1925, when there was a more intensive effort by the agricultural sector to increase the number of agricultural cooperatives and bolster the effectiveness of already existing sovkhozes. In late 1927, after the XV Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, then known as the All-Union Communist Party (bolsheviks), a significant impetus was given to the collectivization effort.[citation needed]

In 1927, a drought shortened the harvest in southern areas of the Ukrainian SSR and North Caucasus. In 1927–1928, the winter tillage area was badly affected due to low snow levels. Despite seed aid from the State, many affected areas were not re-sown. The 1928 harvest was affected by drought in most of the grain producing areas of the Ukrainian SSR. Shortages in the harvest and difficulties with the supply system created difficulties with the food supply in urban areas and destabilized the food supply situation in the USSR in general. In order to alleviate the situation, a system of food rationing was initially implemented in Odessa in the second quarter of 1928, and later spread to Mariupol, Kherson, Kiev, Dnepropetrovsk, and Kharkov. At the beginning of 1929, a similar system was implemented throughout the Soviet Union. Despite the aid from the Soviet Ukrainian and Central governments, many southern rural areas registered occurrences of malnutrition and in some cases hunger and starvation (the affected areas and thus the amount of required food aid was under-counted by authorities). There was also a shortage of forage livestock. Most of Kolkhozes and recently refurnished sovkhozes went through these years with few losses, and some were even able to provide assistance to peasants in the more affected areas (seed and grain for food).[citation needed]

Despite the intense state campaign, the collectivization, which was initially voluntary, was not popular amongst peasants: as of early 1929, only 5.6% of Ukrainian peasant households and 3.8% of arable land were collectivized. In early 1929, the methods employed by the specially empowered authority UkrKolhozcenter changed from a voluntary enrollment to an administrative one. By 1 October 1929, a plan for the creation of kolkhozes was "outperformed" by 239%. As a result, 8.8% of arable land was collectivized.[138]

The next major step toward "all-over collectivization" took place after an article was published by Stalin in Pravda in early November 1929.[citation needed] While initiated by a 10 November–17 meeting of Communist Party Central Committee Twenty-Five Thousanders only trained at special short courses, the main driving force of collectivization and dekulakization in Ukraine became a "poor peasants committee" (komnezamy) and local village councils (silrady) where komnezams members had a voting majority.[citation needed] The USSR Kolhozcenter issued the 10 December 1929, decree on collectivization of livestock within a three-month period (draft animals 100%, cattle 100%, pigs 80%, sheep and goats 60%). This drove many peasants to slaughter their livestock. By 1 January 1930, the percentage of collectivized households almost doubled to 16.4%.[citation needed]

Despite the infamous 5 January 1930 decree, in which the deadline for the complete collectivization of the Ukrainian SSR was set for the period from the end of 1931 to spring 1932, the authorities decided to accelerate the completion of the campaign in autumn 1930. The high expectations of the plan were outperformed by local authorities even without the assistance of the 7,500 Twenty-Five Thousanders,[139] and by March, 70.9% of arable land and 62.8% of peasant households were collectivized. The dekulakization plan also "over-performed". The first stage of dekulakization lasted from second half of January until the beginning of March 1930. Such measures were applied to 309 out of 581 total districts of Ukrainian SSR, which accounted for 2,524,000 of 5,054,000 peasant households. As of 10 March, 61,897 peasants households (2.5%) were dekulakized, while in 1929, the percentage of dekulakized households was 1.4%.[140] Some of the peasants and "weak elements" were arrested and deported "to the north". Many arrested kulaks and "well-to-do" farmers resettled their families to the Urals and Central Asia.[141] The term kulak was ultimately applied to anybody resisting collectivization as many of the so-called kulaks were no more well-off than other peasants.[citation needed]

The fast-track to collectivization incited numerous peasant revolts in Ukraine and in other parts of the Soviet Union. In response to the situation, Pravda published Stalin's article "Dizzy with success", which blamed overeager Party members and declared that "collective farms must not be established by force".[142] Soon, numerous orders and decrees were issued banning the use of force and administrative methods. Some of those dekulakized were declared to have been labeled mistakenly and received their property back, and some returned home. As a result, the collectivization process was rolled back. On 1 May 1933, 38.2% of Ukrainian SSR peasant households and 41.1% of arable land had been collectivized—by the end of August these numbers declined to 29.2% and 35.6% respectively.[citation needed]

A second forced-voluntary collectivization campaign was initiated in the winter of 1931, with significant assistance of the so-called tug-brigades composed of kolkhoz udarniks. Many kulaks, along with their families, were deported from the Ukrainian SSR.[citation needed] According to declassified data, around 300,000 peasants in Ukraine were affected by these policies in 1930–1931. Ukrainians composed 15% of the total 1.8 million kulaks relocated Soviet-wide.[143] Beginning in summer 1931, all further deportations were recommended to be administered only to individuals.[144] This second forced-voluntary collectivization campaign also caused a delay in sowing. During winter and spring 1930–1931, the Ukrainian agricultural authority Narkomzem issued several reports about the significant decline of livestock caused by poor treatment, the absence of forage, stables, and farms, and "kulak sabotage".[citation needed]

According to the first five-year plan, Ukrainian agriculture was to switch from an exclusive orientation of grain to a more diverse output. This included not only an increase in sugar beet crops; other types of agricultural production were expected to be utilized by industry, including cotton, which was established in 1931. This plan anticipated a decrease in grain area and an increase of yield and area for other crops.[citation needed] By 1 July 1931, 65.7% of Ukrainian SSR peasant households and 67.2% of arable land were reported as collectivized, while the main grain and sugar beet production areas were collectivized at levels of 80–90%.[145]

The decree of Central Committee of the Communist Party on 2 August 1931 clarified the all-over collectivization term—in order to be considered complete, the all-over collectivization did not have to reach 100%, but could not be less than 68-70% of peasants households and 75-80% of arable lands. According to the same decree, all-over collectivization was accomplished in the following areas: Northern Caucasus (Kuban), with 88% of households and 92% of arable lands collectivized; Ukraine (South), with 85% and 94% respectively; Ukraine (Right Bank), with 69% and 80%; and Moldavian ASRR (part of Ukrainian SRR), with 68% and 75%.[146] As of the beginning of October 1931, the collectivization of 68% of peasant households, and 72% of arable land was complete.[147]

The plan for the state grain collection in the Ukrainian SSR adopted for 1931 was over-optimistic—510 million poods (8.4 Tg). Drought, administrative distribution of the plan for kolkhozes, and the lack of relevant general management destabilized the situation. Significant amounts of grain remained unharvested. A significant percentage was lost during processing and transportation, or spoiled at elevators (wet grain). The total winter sowing area shrunk by ~2 million hectares. Livestock in kolkhozes remained without forage, which was collected under grain procurement. A similar occurrence happened with respect to seeds and wages awarded to kolhoz members. Grain collection continued until May 1932, but reached only 90% of the planned amounts. By the end of December 1931, the collection plan was 79% accomplished. Many kolkhozes from December 1931 onwards suffered from lack of food, resulting in an increased number of deaths caused by malnutrition, which were registered by OGPU in some areas (Moldavian SSR as a whole and several central rayons of Vinnitsia, Kiev, and North-East rayons of Odessa oblasts)[148] in winter, spring and early summer 1932. By 1932, the sowing campaign of the Ukrainian SSR was implemented with minimal draft power, as most of the remaining horses were incapable of working, while the number of available agricultural tractors was too small to fill the gap.[citation needed]

The government of the Ukrainian SSR tried to remedy the situation, but it had little success. Administrative and territorial reform (oblast creation) in February 1932 also added to the mismanagement. As a result, Moscow had more details about the seed situation than the Ukrainian authorities. In May 1932, in an effort to change the situation, the central Soviet Government provided 7.1 million poods of grain for food for Ukraine and dispatched an additional 700 agricultural tractors originally intended for other regions of the Soviet Union.[citation needed]