Catalan number

The Catalan numbers are a sequence of natural numbers that occur in various counting problems, often involving recursively defined objects. They are named after Eugène Catalan, though they were previously discovered in the 1730s by Minggatu.

The n-th Catalan number can be expressed directly in terms of the central binomial coefficients by

The first Catalan numbers for n = 0, 1, 2, 3, ... are

Properties

[edit]An alternative expression for Cn is

- for

which is equivalent to the expression given above because . This expression shows that Cn is an integer, which is not immediately obvious from the first formula given. This expression forms the basis for a proof of the correctness of the formula.

Another alternative expression is

which can be directly interpreted in terms of the cycle lemma; see below.

The Catalan numbers satisfy the recurrence relations

and

Asymptotically, the Catalan numbers grow as in the sense that the quotient of the n-th Catalan number and the expression on the right tends towards 1 as n approaches infinity.

This can be proved by using the asymptotic growth of the central binomial coefficients, by Stirling's approximation for , or via generating functions.

The only Catalan numbers Cn that are odd are those for which n = 2k − 1; all others are even. The only prime Catalan numbers are C2 = 2 and C3 = 5.[1] More generally, the multiplicity with which a prime p divides Cn can be determined by first expressing n + 1 in base p. For p = 2, the multiplicity is the number of 1 bits, minus 1. For p an odd prime, count all digits greater than (p + 1) / 2; also count digits equal to (p + 1) / 2 unless final; and count digits equal to (p − 1) / 2 if not final and the next digit is counted.[2] The only known odd Catalan numbers that do not have last digit 5 are C0 = 1, C1 = 1, C7 = 429, C31, C127 and C255. The odd Catalan numbers, Cn for n = 2k − 1, do not have last digit 5 if n + 1 has a base 5 representation containing 0, 1 and 2 only, except in the least significant place, which could also be a 3.[3]

The Catalan numbers have the integral representations[4][5]

which immediately yields .

This has a simple probabilistic interpretation. Consider a random walk on the integer line, starting at 0. Let -1 be a "trap" state, such that if the walker arrives at -1, it will remain there. The walker can arrive at the trap state at times 1, 3, 5, 7..., and the number of ways the walker can arrive at the trap state at time is . Since the 1D random walk is recurrent, the probability that the walker eventually arrives at -1 is .

Applications in combinatorics

[edit]There are many counting problems in combinatorics whose solution is given by the Catalan numbers. The book Enumerative Combinatorics: Volume 2 by combinatorialist Richard P. Stanley contains a set of exercises which describe 66 different interpretations of the Catalan numbers. Following are some examples, with illustrations of the cases C3 = 5 and C4 = 14.

- Cn is the number of Dyck words[6] of length 2n. A Dyck word is a string consisting of n X's and n Y's such that no initial segment of the string has more Y's than X's. For example, the following are the Dyck words up to length 6:

- Re-interpreting the symbol X as an open parenthesis and Y as a close parenthesis, Cn counts the number of expressions containing n pairs of parentheses which are correctly matched:

- Cn is the number of different ways n + 1 factors can be completely parenthesized (or the number of ways of associating n applications of a binary operator, as in the matrix chain multiplication problem). For n = 3, for example, we have the following five different parenthesizations of four factors:

- Successive applications of a binary operator can be represented in terms of a full binary tree, by labeling each leaf a, b, c, d. It follows that Cn is the number of full binary trees with n + 1 leaves, or, equivalently, with a total of n internal nodes:

- Cn is the number of non-isomorphic ordered (or plane) trees with n + 1 vertices.[7] See encoding general trees as binary trees. For example, Cn is the number of possible parse trees for a sentence (assuming binary branching), in natural language processing.

- Cn is the number of monotonic lattice paths along the edges of a grid with n × n square cells, which do not pass above the diagonal. A monotonic path is one which starts in the lower left corner, finishes in the upper right corner, and consists entirely of edges pointing rightwards or upwards. Counting such paths is equivalent to counting Dyck words: X stands for "move right" and Y stands for "move up".

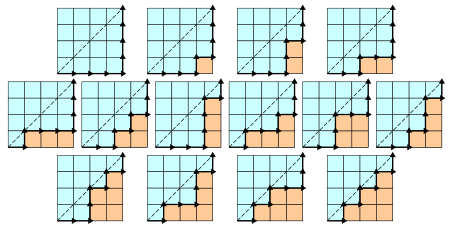

The following diagrams show the case n = 4:

This can be represented by listing the Catalan elements by column height:[8]

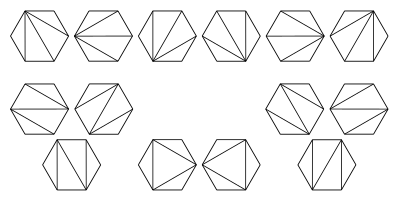

- A convex polygon with n + 2 sides can be cut into triangles by connecting vertices with non-crossing line segments (a form of polygon triangulation). The number of triangles formed is n and the number of different ways that this can be achieved is Cn. The following hexagons illustrate the case n = 4:

- Cn is the number of stack-sortable permutations of {1, ..., n}. A permutation w is called stack-sortable if S(w) = (1, ..., n), where S(w) is defined recursively as follows: write w = unv where n is the largest element in w and u and v are shorter sequences, and set S(w) = S(u)S(v)n, with S being the identity for one-element sequences.

- Cn is the number of permutations of {1, ..., n} that avoid the permutation pattern 123 (or, alternatively, any of the other patterns of length 3); that is, the number of permutations with no three-term increasing subsequence. For n = 3, these permutations are 132, 213, 231, 312 and 321. For n = 4, they are 1432, 2143, 2413, 2431, 3142, 3214, 3241, 3412, 3421, 4132, 4213, 4231, 4312 and 4321.

- Cn is the number of noncrossing partitions of the set {1, ..., n}. A fortiori, Cn never exceeds the n-th Bell number. Cn is also the number of noncrossing partitions of the set {1, ..., 2n} in which every block is of size 2.

- Cn is the number of ways to tile a stairstep shape of height n with n rectangles. Cutting across the anti-diagonal and looking at only the edges gives full binary trees. The following figure illustrates the case n = 4:

- Cn is the number of ways to form a "mountain range" with n upstrokes and n downstrokes that all stay above a horizontal line. The mountain range interpretation is that the mountains will never go below the horizon.

| * | 1 way | |

| /\ | 1 way | |

| /\ /\/\,/\ |

2 ways | |

| /\ /\/\/\/\/\ /\/\/\,/\/\,/\/\,/\,/\ |

5 ways |

- Cn is the number of standard Young tableaux whose diagram is a 2-by-n rectangle. In other words, it is the number of ways the numbers 1, 2, ..., 2n can be arranged in a 2-by-n rectangle so that each row and each column is increasing. As such, the formula can be derived as a special case of the hook-length formula.

123 124 125 134 135 456 356 346 256 246

- is the number of length n sequences that start with , and can increase by either or , or decrease by any number (to at least ). For these are . From a Dyck path, start a counter at 0. An X increases the counter by 1 and a Y decreases it by 1. Record the values at only the X's. Compared to the similar representation of the Bell numbers, only is missing.

Proof of the formula

[edit]There are several ways of explaining why the formula

solves the combinatorial problems listed above. The first proof below uses a generating function. The other proofs are examples of bijective proofs; they involve literally counting a collection of some kind of object to arrive at the correct formula.

First proof

[edit]We first observe that all of the combinatorial problems listed above satisfy Segner's[9] recurrence relation

For example, every Dyck word w of length ≥ 2 can be written in a unique way in the form

- w = Xw1Yw2

with (possibly empty) Dyck words w1 and w2.

The generating function for the Catalan numbers is defined by

The recurrence relation given above can then be summarized in generating function form by the relation

in other words, this equation follows from the recurrence relation by expanding both sides into power series. On the one hand, the recurrence relation uniquely determines the Catalan numbers; on the other hand, interpreting xc2 − c + 1 = 0 as a quadratic equation of c and using the quadratic formula, the generating function relation can be algebraically solved to yield two solution possibilities

- or .

From the two possibilities, the second must be chosen because only the second gives

- .

The square root term can be expanded as a power series using the binomial series

Thus,

Second proof

[edit]

We count the number of paths which start and end on the diagonal of an n × n grid. All such paths have n right and n up steps. Since we can choose which of the 2n steps are up or right, there are in total monotonic paths of this type. A bad path crosses the main diagonal and touches the next higher diagonal (red in the illustration).

The part of the path after the higher diagonal is then flipped about that diagonal, as illustrated with the red dotted line. This swaps all the right steps to up steps and vice versa. In the section of the path that is not reflected, there is one more up step than right steps, so therefore the remaining section of the bad path has one more right step than up steps. When this portion of the path is reflected, it will have one more up step than right steps.

Since there are still 2n steps, there are now n + 1 up steps and n − 1 right steps. So, instead of reaching (n, n), all bad paths after reflection end at (n − 1, n + 1). Because every monotonic path in the (n − 1) × (n + 1) grid meets the higher diagonal, and because the reflection process is reversible, the reflection is therefore a bijection between bad paths in the original grid and monotonic paths in the new grid.

The number of bad paths is therefore:

and the number of Catalan paths (i.e. good paths) is obtained by removing the number of bad paths from the total number of monotonic paths of the original grid,

In terms of Dyck words, we start with a (non-Dyck) sequence of n X's and n Y's and interchange all X's and Y's after the first Y that violates the Dyck condition. After this Y, note that there is exactly one more Y than there are Xs.

Third proof

[edit]This bijective proof provides a natural explanation for the term n + 1 appearing in the denominator of the formula for Cn. A generalized version of this proof can be found in a paper of Rukavicka Josef (2011).[10]

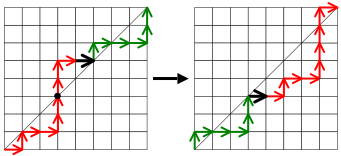

Given a monotonic path, the exceedance of the path is defined to be the number of vertical edges above the diagonal. For example, in Figure 2, the edges above the diagonal are marked in red, so the exceedance of this path is 5.

Given a monotonic path whose exceedance is not zero, we apply the following algorithm to construct a new path whose exceedance is 1 less than the one we started with.

- Starting from the bottom left, follow the path until it first travels above the diagonal.

- Continue to follow the path until it touches the diagonal again. Denote by X the first such edge that is reached.

- Swap the portion of the path occurring before X with the portion occurring after X.

In Figure 3, the black dot indicates the point where the path first crosses the diagonal. The black edge is X, and we place the last lattice point of the red portion in the top-right corner, and the first lattice point of the green portion in the bottom-left corner, and place X accordingly, to make a new path, shown in the second diagram.

The exceedance has dropped from 3 to 2. In fact, the algorithm causes the exceedance to decrease by 1 for any path that we feed it, because the first vertical step starting on the diagonal (at the point marked with a black dot) is the only vertical edge that changes from being above the diagonal to being below it when we apply the algorithm - all the other vertical edges stay on the same side of the diagonal.

It can be seen that this process is reversible: given any path P whose exceedance is less than n, there is exactly one path which yields P when the algorithm is applied to it. Indeed, the (black) edge X, which originally was the first horizontal step ending on the diagonal, has become the last horizontal step starting on the diagonal. Alternatively, reverse the original algorithm to look for the first edge that passes below the diagonal.

This implies that the number of paths of exceedance n is equal to the number of paths of exceedance n − 1, which is equal to the number of paths of exceedance n − 2, and so on, down to zero. In other words, we have split up the set of all monotonic paths into n + 1 equally sized classes, corresponding to the possible exceedances between 0 and n. Since there are monotonic paths, we obtain the desired formula

Figure 4 illustrates the situation for n = 3. Each of the 20 possible monotonic paths appears somewhere in the table. The first column shows all paths of exceedance three, which lie entirely above the diagonal. The columns to the right show the result of successive applications of the algorithm, with the exceedance decreasing one unit at a time. There are five rows, that is C3 = 5, and the last column displays all paths no higher than the diagonal.

Using Dyck words, start with a sequence from . Let be the first X that brings an initial subsequence to equality, and configure the sequence as . The new sequence is .

Fourth proof

[edit]This proof uses the triangulation definition of Catalan numbers to establish a relation between Cn and Cn+1.

Given a polygon P with n + 2 sides and a triangulation, mark one of its sides as the base, and also orient one of its 2n + 1 total edges. There are (4n + 2)Cn such marked triangulations for a given base.

Given a polygon Q with n + 3 sides and a (different) triangulation, again mark one of its sides as the base. Mark one of the sides other than the base side (and not an inner triangle edge). There are (n + 2)Cn + 1 such marked triangulations for a given base.

There is a simple bijection between these two marked triangulations: We can either collapse the triangle in Q whose side is marked (in two ways, and subtract the two that cannot collapse the base), or, in reverse, expand the oriented edge in P to a triangle and mark its new side.

Thus

- .

Write

Because

we have

Applying the recursion with gives the result.

Fifth proof

[edit]This proof is based on the Dyck words interpretation of the Catalan numbers, so is the number of ways to correctly match n pairs of brackets. We denote a (possibly empty) correct string with c and its inverse with c'. Since any c can be uniquely decomposed into , summing over the possible lengths of immediately gives the recursive definition

- .

Let b be a balanced string of length 2n, i.e. b contains an equal number of and , so . A balanced string can also be uniquely decomposed into either or , so

Any incorrect (non-Catalan) balanced string starts with , and the remaining string has one more than , so

Also, from the definitions, we have:

Therefore, as this is true for all n,

Sixth proof

[edit]This proof is based on the Dyck words interpretation of the Catalan numbers and uses the cycle lemma of Dvoretzky and Motzkin.[11][12]

We call a sequence of X's and Y's dominating if, reading from left to right, the number of X's is always strictly greater than the number of Y's. The cycle lemma[13] states that any sequence of X's and Y's, where , has precisely dominating circular shifts. To see this, arrange the given sequence of X's and Y's in a circle. Repeatedly removing XY pairs leaves exactly X's. Each of these X's was the start of a dominating circular shift before anything was removed. For example, consider . This sequence is dominating, but none of its circular shifts , , and are.

A string is a Dyck word of X's and Y's if and only if prepending an X to the Dyck word gives a dominating sequence with X's and Y's, so we can count the former by instead counting the latter. In particular, when , there is exactly one dominating circular shift. There are sequences with exactly X's and Y's. For each of these, only one of the circular shifts is dominating. Therefore there are distinct sequences of X's and Y's that are dominating, each of which corresponds to exactly one Dyck word.

Hankel matrix

[edit]The n × n Hankel matrix whose (i, j) entry is the Catalan number Ci+j−2 has determinant 1, regardless of the value of n. For example, for n = 4 we have

Moreover, if the indexing is "shifted" so that the (i, j) entry is filled with the Catalan number Ci+j−1 then the determinant is still 1, regardless of the value of n. For example, for n = 4 we have

Taken together, these two conditions uniquely define the Catalan numbers.

Another feature unique to the Catalan–Hankel matrix is that the n × n submatrix starting at 2 has determinant n + 1.

et cetera.

History

[edit]

The Catalan sequence was described in the 18th century by Leonhard Euler, who was interested in the number of different ways of dividing a polygon into triangles. The sequence is named after Eugène Charles Catalan, who discovered the connection to parenthesized expressions during his exploration of the Towers of Hanoi puzzle. The reflection counting trick (second proof) for Dyck words was found by Désiré André in 1887.

The name “Catalan numbers” originated from John Riordan.[14]

In 1988, it came to light that the Catalan number sequence had been used in China by the Mongolian mathematician Mingantu by 1730.[15][16] That is when he started to write his book Ge Yuan Mi Lu Jie Fa [The Quick Method for Obtaining the Precise Ratio of Division of a Circle], which was completed by his student Chen Jixin in 1774 but published sixty years later. Peter J. Larcombe (1999) sketched some of the features of the work of Mingantu, including the stimulus of Pierre Jartoux, who brought three infinite series to China early in the 1700s.

For instance, Ming used the Catalan sequence to express series expansions of and in terms of .

Generalizations

[edit]The Catalan numbers can be interpreted as a special case of the Bertrand's ballot theorem. Specifically, is the number of ways for a candidate A with n + 1 votes to lead candidate B with n votes.

The two-parameter sequence of non-negative integers is a generalization of the Catalan numbers. These are named super-Catalan numbers, per Ira Gessel. These should not confused with the Schröder–Hipparchus numbers, which sometimes are also called super-Catalan numbers.

For , this is just two times the ordinary Catalan numbers, and for , the numbers have an easy combinatorial description. However, other combinatorial descriptions are only known[17] for and ,[18] and it is an open problem to find a general combinatorial interpretation.

Sergey Fomin and Nathan Reading have given a generalized Catalan number associated to any finite crystallographic Coxeter group, namely the number of fully commutative elements of the group; in terms of the associated root system, it is the number of anti-chains (or order ideals) in the poset of positive roots. The classical Catalan number corresponds to the root system of type . The classical recurrence relation generalizes: the Catalan number of a Coxeter diagram is equal to the sum of the Catalan numbers of all its maximal proper sub-diagrams.[19]

The Catalan numbers are a solution of a version of the Hausdorff moment problem.[20]

Catalan k-fold convolution

[edit]The Catalan k-fold convolution, where k = m, is:[21]

See also

[edit]- Associahedron

- Bertrand's ballot theorem

- Binomial transform

- Catalan's triangle

- Catalan–Mersenne number

- Delannoy number

- Fuss–Catalan number

- List of factorial and binomial topics

- Lobb numbers

- Motzkin number

- Narayana number

- Narayana polynomials

- Schröder number

- Schröder–Hipparchus number

- Semiorder

- Tamari lattice

- Wedderburn–Etherington number

- Wigner's semicircle law

Notes

[edit]- ^ Koshy, Thomas; Salmassi, Mohammad (2006). "Parity and primality of Catalan numbers" (PDF). The College Mathematics Journal. 37 (1): 52–53. doi:10.2307/27646275. JSTOR 27646275.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A000108 (Catalan numbers)". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ "Catalan Number".

- ^ Choi, Hayoung; Yeh, Yeong-Nan; Yoo, Seonguk (2020), "Catalan-like number sequences and Hausdorff moment sequences", Discrete Mathematics, 343 (5): 111808, 11, arXiv:1809.07523, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2019.111808, MR 4052255, S2CID 214165563, Example 3.1

- ^ Feng, Qi; Bai-Ni, Guo (2017), "Integral Representations of the Catalan Numbers and Their Applications", Mathematics, 5 (3): 40, doi:10.3390/math5030040,Theorem 1

- ^ Dyck paths

- ^ Stanley p.221 example (e)

- ^ Črepinšek, Matej; Mernik, Luka (2009). "An efficient representation for solving Catalan number related problems" (PDF). International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics. 56 (4): 589–604.

- ^ A. de Segner, Enumeratio modorum, quibus figurae planae rectilineae per diagonales dividuntur in triangula. Novi commentarii academiae scientiarum Petropolitanae 7 (1758/59) 203–209.

- ^ Rukavicka Josef (2011), On Generalized Dyck Paths, Electronic Journal of Combinatorics online

- ^ Dershowitz, Nachum; Zaks, Shmuel (1980), "Enumerations of ordered trees", Discrete Mathematics, 31: 9–28, doi:10.1016/0012-365x(80)90168-5, hdl:2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t3kw6z60d

- ^ Dvoretzky, Aryeh; Motzkin, Theodore (1947), "A problem of arrangements", Duke Mathematical Journal, 14 (2): 305–313, doi:10.1215/s0012-7094-47-01423-3

- ^ Dershowitz, Nachum; Zaks, Shmuel (January 1990). "The Cycle Lemma and Some Applications" (PDF). European Journal of Combinatorics. 11 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1016/S0195-6698(13)80053-4.

- ^ Stanley, Richard P. (2021). "Enumerative and Algebraic Combinatorics in the 1960's and 1970's". arXiv:2105.07884 [math.HO].

- ^ Larcombe, Peter J. "The 18th century Chinese discovery of the Catalan numbers" (PDF).

- ^ "Ming Antu, the First Inventor of Catalan Numbers in the World". Archived from the original on 2020-01-31. Retrieved 2014-06-24.

- ^ Chen, Xin; Wang, Jane (2012). "The super Catalan numbers S(m, m + s) for s ≤ 4". arXiv:1208.4196 [math.CO].

- ^ Gheorghiciuc, Irina; Orelowitz, Gidon (2020). "Super-Catalan Numbers of the Third and Fourth Kind". arXiv:2008.00133 [math.CO].

- ^ Sergey Fomin and Nathan Reading, "Root systems and generalized associahedra", Geometric combinatorics, IAS/Park City Math. Ser. 13, American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2007, pp 63–131. arXiv:math/0505518

- ^ Choi, Hayoung; Yeh, Yeong-Nan; Yoo, Seonguk (2020), "Catalan-like number sequences and Hausdorff moment sequences", Discrete Mathematics, 343 (5): 111808, 11, arXiv:1809.07523, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2019.111808, MR 4052255, S2CID 214165563

- ^ Bowman, D.; Regev, Alon (2014). "Counting symmetry: classes of dissections of a convex regular polygon". Adv. Appl. Math. 56: 35–55. arXiv:1209.6270. doi:10.1016/j.aam.2014.01.004. S2CID 15430707.

References

[edit]- Stanley, Richard P. (2015), Catalan numbers. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-42774-7.

- Conway and Guy (1996) The Book of Numbers. New York: Copernicus, pp. 96–106.

- Gardner, Martin (1988), Time Travel and Other Mathematical Bewilderments, New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, pp. 253–266 (Ch. 20), Bibcode:1988ttom.book.....G, ISBN 0-7167-1924-X

- Koshy, Thomas (2008), Catalan Numbers with Applications, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533454-8

- Koshy, Thomas & Zhenguang Gao (2011) "Some divisibility properties of Catalan numbers", Mathematical Gazette 95:96–102.

- Larcombe, P.J. (1999). "The 18th century Chinese discovery of the Catalan numbers" (PDF). Mathematical Spectrum. 32: 5–7.

- Stanley, Richard P. (1999), Enumerative combinatorics. Vol. 2, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, vol. 62, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-56069-6, MR 1676282

- Egecioglu, Omer (2009), A Catalan–Hankel Determinant Evaluation (PDF)

- Gheorghiciuc, Irina; Orelowitz, Gidon (2020), Super-Catalan Numbers of the Third and Fourth Kind, arXiv:2008.00133

External links

[edit]- Stanley, Richard P. (1998), Catalan addendum to Enumerative Combinatorics, Volume 2 (PDF)

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Catalan Number". MathWorld.

- Davis, Tom: Catalan numbers. Still more examples.

- "Equivalence of Three Catalan Number Interpretations" from The Wolfram Demonstrations Project [1]

Learning materials related to Partition related number triangles at Wikiversity

Learning materials related to Partition related number triangles at Wikiversity

![{\displaystyle \sum _{i_{1}+\cdots +i_{m}=n \atop i_{1},\ldots ,i_{m}\geq 0}C_{i_{1}}\cdots C_{i_{m}}={\begin{cases}{\dfrac {m(n+1)(n+2)\cdots (n+m/2-1)}{2(n+m/2+2)(n+m/2+3)\cdots (n+m)}}C_{n+m/2},&m{\text{ even,}}\\[5pt]{\dfrac {m(n+1)(n+2)\cdots (n+(m-1)/2)}{(n+(m+3)/2)(n+(m+3)/2+1)\cdots (n+m)}}C_{n+(m-1)/2},&m{\text{ odd.}}\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.riteme.site/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/45120dc51e2755ca8b30b3ae9e3e6c8717b268f1)