Carmental Gate

The Carmental Gate, also known by its Latin name as the Porta Carmentalis, was a double gate in the Servian Walls of ancient Rome. It was named for a nearby shrine to the goddess or nymph Carmenta,[1] whose importance in early Roman religion is also indicated by the assignment of one of the fifteen flamines to her cult, and by the archaic festival in her honor, the Carmentalia. The shrine was to the right as one exited the gate.

The gate's two arches seem to have been set at angles, and were known by separate names. It was unlucky to leave the city through the arch called Porta Scelerata ("Accursed Gate"), which was supposed to have been named for the military disaster at Cremera in 479 or 478 BC, since the 306 Fabii who died had departed through it.[2] The Servian Walls, however, did not exist at that time.[3] The accursed nature of the gate probably derives from the transport of corpses out of the city proper to funeral pyres on the Campus Martius.[4] The family tomb of the Claudii was located outside the Carmental Gate.[5]

The other gate was the Porta Triumphalis. A governor returning from his province could not enter through this gate unless he had been awarded a triumph. It therefore must have been routine to use the Porta Scelerata for entering, and the Triumphalis for exiting. Funeral processions reversed the normal direction of traffic flow for the Scelerata, as the triumphal procession did for the Triumphalis. Augustus was accorded the special honor of having his funeral procession exit by the Triumphalis.[6]

The temples of Mater Matuta,[7] Fortuna, [7] Juno Sospita, and Spes were located nearby, the later two at the Forum Olitorium, Rome's vegetable market.[8]

The Carmental Gate was rebuilt by Domitian and topped with a sculpture group of a triumphal chariot drawn by elephants, to celebrate his campaign against the Sarmatians and the Marcomanni.[9] The gate is depicted in relief sculpture dating to the reign of Marcus Aurelius.[10] It was eventually destroyed by order of the emperor Constantine I.[11]

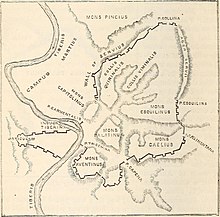

The Vicus Iugarius forked just before reaching the Carmental Gate, with one branch passing through the Forum Holitorium by making a right curve around the foot of the Capitoline Hill, and the other passing through the Forum Boarium to the mouth of the Cloaca Maxima on the Tiber. The precise location of the Carmental Gate itself remains unclear, despite excavations in the area from the late 1930s onward.[12] Livy names the Carmental Gate as the point of entry for a ritual procession undertaken in 207 BC as part of an expiatory sacrifice for Juno. Two white cows were led from the Temple of Apollo through the gate and along the Vicus Iugarius to the Forum.[13]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Vergil, Aeneid 8.337–341; Dionysius of Halicarnassus 1.32.3; Festus 450 in the edition of Lindsay; Solinus 1.13: Lawrence Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), p. 301.

- ^ Festus 450L; Ovid, Fasti 2.201–204; Cassius Dio frg. 20.3 (21.3); De viris illustribus 14.3–5; Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 301.

- ^ Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 301.

- ^ Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 301.

- ^ T.P. Wiseman, "The Legends of the Patrician Claudii," in Clio's Cosmetics (Bristol Phoenix Press, 2003 reprint, originally published 1979), p. 94.

- ^ Cicero, In Pisonem 55; Josephus, Jewish Wars 7.5.4.130–131; Tacitus, Annales 1.8.4; Suetonius, Augustus 100.2; Cassius Dio 56.42.1; Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 301.

- ^ a b Christopher Smith, "Worshipping Mater Matuta: Ritual and Context," in Religion in Archaic and Republican Rome and Italy: Evidence and Experience (Edinburgh University Press, 2000), p. 145.

- ^ Burn (1871), p. 305.

- ^ Martial 8.65.1–12; Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 301.

- ^ Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 301.

- ^ Förtsch, Reinhard. (2006) "Arcus: [11] Domitiani." Brills New Pauly. Retrieved from https://referenceworks-brillonline-com.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/arcus-e133120?s.num=0&s.f.s2_parent=s.f.book.brill-s-new-pauly&s.q=arcus.

- ^ Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 301.

- ^ Livy 27.37.11–15; J.J. Pollitt, The Art of Rome, C. 753 B.C.-A.D. 337: Sources and Documents (Cambridge University Press, 1983, originally published in 1966), p. 49.