Islamabad

Islamabad

اسلام آباد Islām-ābād | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): Isloo, The Green City | |

| Coordinates: 33°41′35″N 73°03′50″E / 33.69306°N 73.06389°E | |

| Country | |

| Adm. Unit | Islamabad Capital Territory |

| Constructed | 1960 |

| Established | 14 August 1967[1] |

| Administrative Areas | 01

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Metropolitan Corporation |

| • Body | Capital Development Authority |

| • Mayor | None (vacant)[a] |

| • Constituensy | NA-46 Islamabad-I NA-47 Islamabad-II NA-48 Islamabad-III |

| • Deputy Commissioner | Irfan Nawaz Memon (BPS-19 PAS)[3] |

| Area | |

• City | 220.15 km2 (85.00 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 220.15 km2 (85.00 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 906.50 km2 (350.00 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 666 m (2,185 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 1,584 m (5,197 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 417 m (1,368 ft) |

| Population | |

• City | 1,108,872 |

| • Rank | 10th |

| • Density | 5,037/km2 (13,050/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,363,863 |

| • Metro density | 2,608/km2 (6,750/sq mi) |

| • Rank (Metro) | 4th |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PKT) |

| Postcode | 44000 |

| Area code | 051 |

| Website | ictadministration |

Islamabad (/ɪzˈlɑːməbæd/ ⓘ;[6] Urdu: اسلامآباد, romanized: Islāmābād, [ɪs.lɑːm.ɑː.bɑːd̪] ⓘ; transl. 'City of Islam') is the capital city of Pakistan.[7] It is the country's tenth-most populous city with a population of 1,108,872 people[5][8] and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital Territory. Built as a planned city in the 1960s and established in 1967, it replaced Karachi as Pakistan's national capital.

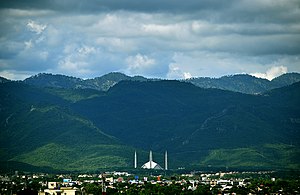

The Greek architect Constantinos Apostolou Doxiadis developed Islamabad's master plan, in which he divided it into eight zones; the city comprises administrative, diplomatic enclave, residential areas, educational and industrial sectors, commercial areas, as well as rural and green areas administered by the Islamabad Metropolitan Corporation with support from the Capital Development Authority. Islamabad is known for its parks and forests, including the Margalla Hills National Park and the Shakarparian.[9] It is home to several landmarks, including the country's flagship Faisal Mosque, which is the world's fifth-largest mosque. Other prominent landmarks include the Pakistan Monument and Democracy Square.[10][11][12]

Rated as Gamma + by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network,[13] Islamabad has one of the highest costs of living in Pakistan. The city's populace is dominated by both middle and upper-middle class citizens.[14][15] Islamabad is home to twenty universities, including Bahria University, Quaid-e-Azam University, PIEAS, COMSATS University, and NUST.[16] It is also rated as one of the safest cities in Pakistan and has an expansive RFID-enabled surveillance system with almost 2,000 active CCTV cameras.[17][18]

Toponymy

The name Islamabad means City of Islam. It is derived from two words: Islam and abad. Islam refers to the religion of Islam, Pakistan's state religion, and -abad is a Persian suffix meaning cultivated place, indicating an inhabited place or city.[19] According to a history book by Muhammad Ismail Zabeeh, teacher and poet Qazi Abdur Rehman Amritsari proposed the name of the city.[20][21]

Occasionally in writing, Islamabad is colloquially abbreviated ISB. Such usage originated in SMS language, in part due to the IATA location identifier for the Islamabad International Airport.

History

Early history

Islamabad Capital Territory, located on the Pothohar Plateau of the northern Punjab region, is considered one of the earliest sites of human settlement in Asia.[22] Some of the earliest Stone Age artefacts in the world have been found on the plateau, dating from 100,000 to 500,000 years ago. Rudimentary stones recovered from the terraces of the Soan River testify to the endeavours of early man in the inter-glacial period.[23] Items of pottery and utensils dating back to prehistory have been found.[24]

Excavations by Dr. Abdul Ghafoor Lone reveal evidence of a prehistoric culture in the area. Relics and human skulls have been found dating back to 5000 BCE that indicate the region was home to Neolithic peoples who settled on the banks of the Soan[22] and who later developed small communities in the region around 3000 BCE.[23][25]

The Indus Valley civilization flourished in the region between the 23rd and 18th centuries BCE. Later the area was an early settlement of the Aryan community which migrated into the region from Central Asia.[22] Many great armies such as those of Zahiruddin Babur, Genghis Khan, Timur and Ahmad Shah Durrani crossed the region during their invasions of the Indian subcontinent.[22][26] In 2015–16, the Federal Department of Archaeology and Museums, with the financial support of National Fund for Cultural Heritage, carried out initial archaeological excavations in which unearthed the remains of a Buddhist stupa at Ban Faqiran, near the Shah Allah Ditta caves, which was dated to the 2nd to the 5th century CE.[27]

-

15th-century Pharwala Fort beside the Swaan River

-

The Shrine of Meher Ali Shah was completed immediately before construction began on the future capital city just east of the shrine

-

The caves at Shah Allah Ditta, on Islamabad's outskirts, were part of an ancient Buddhist monastic community

-

The restored village of Saidpur predates the surrounding city of Islamabad

Construction and development

When Pakistan gained independence in 1947, the southern port city of Karachi was its provisional national capital. In 1958, a commission was constituted to select a suitable site near Rawalpindi for the national capital with particular emphasis on location, climate, logistics, and defence requirements, along with other attributes. After extensive study, research, and a thorough review of potential sites, the commission recommended the area northeast of Rawalpindi in 1959 which was used as provisional capital from that year on.[28][29] In the 1960s, Islamabad was constructed as a forward capital for several reasons.[30] Karachi was also located at the southern end of the country, and exposed to attacks from the Arabian Sea. Pakistan needed a capital that was easily accessible from all parts of the country.[28][31] Karachi, a business centre, was also considered unsuitable partly because of intervention of business interests in government affairs.[32] The newly selected location of Islamabad was closer to the army headquarters in Rawalpindi and the disputed territory of Kashmir in the north.[22]

A Greek firm of architects, led by Konstantinos Apostolos Doxiadis, designed the master plan of the city based on a grid plan which was triangular in shape with its apex towards the Margalla Hills.[33] The capital was not moved directly from Karachi to Islamabad; it was first shifted temporarily to Rawalpindi in the early 1960s and then to Islamabad when essential development work was completed in 1966.[34] In 1981, Islamabad separated from Punjab province to form Capital Territory. Such world-renowned architects as Edward Durell Stone and Gio Ponti have been associated with the city's development.[35]

Recent history

Islamabad has attracted people from all over Pakistan, making it one of the most cosmopolitan and urbanised cities of Pakistan.[36] As the capital city it has hosted numerous important meetings, such as the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation summit in 2004.[37]

The city suffered damage from the 2005 Kashmir earthquake which had a magnitude of 7.6.[38] Islamabad has experienced a series of terrorist incidents including the July 2007 Siege of Lal Masjid (Red Mosque), the June 2008 Danish embassy bombing, and the September 2008 Marriott bombing.[39] In 2011, four terrorism incidents occurred in the city, killing four people, including the murder of the Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer.[40]

Construction of the Rawalpindi-Islamabad Metrobus, the region's first mass transit line, began in February 2014 and was completed in March 2015. The Rawalpindi Development Authority built the project at a cost of approximately Rs 24 billion, which was shared by both the Federal government and the provincial government of Punjab.[41]

Geography

-

Satellite view of Islamabad-Rawalpindi Metropolitan Area with Margalla Hills in the north.

-

Margalla Hills, Islamabad

-

Islamabad's verdant cityscape merges with the Margalla Hills

-

Islamabad's lush landscape

-

Islamabad's deciduous trees change colours in autumn

Islamabad is located at 33°26′N 73°02′E / 33.43°N 73.04°E at the northern edge of the Pothohar Plateau and at the foot of the Margalla Hills in Islamabad Capital Territory. Its elevation is 540 metres (1,770 ft).[42][43] The modern capital and the ancient Gakhar city of Rawalpindi form a conurbation and are commonly referred to as the Twin Cities.[44][32]

To the northeast of the city lies the colonial era hill station of Murree, and to the north lies the Haripur District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Kahuta lies on the southeast, Taxila, Wah Cantt, and Attock District to the northwest, Gujar Khan, Rawat, and Mandrah on the southeast, and the metropolis of Rawalpindi to the south and southwest. Islamabad is located 120 kilometres (75 mi) SSW of Muzaffarabad, 185 kilometres (115 mi) east of Peshawar and 295 kilometres (183 mi) NNW of Lahore.

Islamabad covers an area of 906 square kilometres (350 sq mi).[45] A further 2,717 square kilometres (1,049 sq mi) area is known as the Specified Area, with the Margala Hills in the north and northeast. The southern portion of the city is an undulating plain. It is drained by the Kurang River, on which the Rawal Dam is located.[35]

Climate

Islamabad has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cwa), with five seasons: Winter (November–February), Spring (March and April), Summer (May and June), Rainy Monsoon (July and August) and Autumn (September and October). The hottest month is June, where average highs routinely exceed 38 °C (100.4 °F). The wettest month is July, with heavy rainfalls and evening thunderstorms with the possibility of cloudburst and flooding. The coolest month is January.

Islamabad's micro-climate is regulated by three artificial reservoirs: Rawal, Simli, and Khanpur Dam. The latter is located on the Haro River near the town of Khanpur, about 40 kilometres (25 mi) from Islamabad. Simli Dam is 30 kilometres (19 mi) north of Islamabad. 220 acres (89 ha) of the city consists of Margalla Hills National Park. Loi Bher Forest is situated along the Islamabad Highway, covering an area of 1,087 acres (440 ha).[46] The highest monthly rainfall of 743.3 mm (29.26 in) was recorded during July 1995.[47] Winters generally feature dense fog in the mornings and sunny afternoons. In the city, temperatures stay mild, with snowfall over the higher-elevation points on nearby hill stations, notably Murree and Nathia Gali. The temperatures range from 13 °C (55 °F) in January to 38 °C (100 °F) in June. The highest recorded temperature was 46.6 °C (115.9 °F) on 23 June 2005 while the lowest temperature was −6.0 °C (21.2 °F) on 17 January 1967.[48][49] Light snowfall sometimes happens on the peaks of the hills visible from the city, though this is rare.[50] Snowfall does not occur in the city itself. On 23 July 2001, Islamabad received a record-breaking 620 mm (24 in) of rainfall in just 10 hours. It was the heaviest rainfall in Islamabad in the past 100 years and the highest rainfall in 24 hours as well.[51][52] Water supply is strained, leading to project proposals like the Ghazi Barotha water supply project.

| Climate data for Islamabad (1991-2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.0 (77.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

37.0 (98.6) |

44.0 (111.2) |

45.6 (114.1) |

48.6 (119.5) |

45.0 (113.0) |

42.0 (107.6) |

38.1 (100.6) |

38.0 (100.4) |

32.2 (90.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

48.6 (119.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

36.1 (97.0) |

38.3 (100.9) |

35.4 (95.7) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.4 (92.1) |

30.9 (87.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

28.9 (84.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

29.1 (84.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

22.2 (71.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

15.2 (59.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10 (14) |

−8 (18) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

13 (55) |

15.2 (59.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.3 (55.9) |

5.7 (42.3) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55.2 (2.17) |

99.5 (3.92) |

180.5 (7.11) |

120.8 (4.76) |

39.9 (1.57) |

78.4 (3.09) |

310.6 (12.23) |

317.0 (12.48) |

135.4 (5.33) |

34.4 (1.35) |

17.7 (0.70) |

25.9 (1.02) |

1,415.3 (55.73) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 6.4 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 79.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 195.7 | 187.1 | 202.3 | 252.4 | 319.0 | 300.1 | 264.4 | 250.7 | 262.2 | 275.5 | 247.9 | 195 | 2,952.3 |

| Source 1: NOAA (sun, 1961-1990)[53][54] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: PMD (extremes)[55] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

| Zones in Islamabad | ||

|---|---|---|

| Zone | Area | |

| acres | km2 | |

| I | 54,958.25 | 222.4081 |

| II | 9,804.92 | 39.6791 |

| III | 50,393.01 | 203.9333 |

| IV | 69,814.35 | 282.5287 |

| V | 39,029.45 | 157.9466 |

| Source: | Lahore Real Estate[56] | |

Civic administration

The Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) Administration, generally known as ICT Administration or Islamabad Administration, is the civil administration as well as main law and order agency of the Federal Capital.

The local government authority of the city is the Islamabad Metropolitan Corporation (IMC) with some help from Capital Development Authority (CDA), which oversees the planning, development, construction, and administration of the city.[57][58] Islamabad Capital Territory is divided into eight zones: Administrative Zone, Commercial District, Educational Sector, Industrial Sector, Diplomatic Enclave, Residential Areas, Rural Areas and Green Area.[59] Islamabad city is divided into five major zones: Zone I, Zone II, Zone III, Zone IV, and Zone V. Out of these, Zone IV is the largest in area.[56] Zone I consists mainly of all the developed residential sectors while Zone II consists of the under-developed residential sectors. Each residential sector is identified by a letter of the alphabet and a number, and covers an area of approximately 2 km × 2 km (1+1⁄4 mi × 1+1⁄4 mi). The sectors are lettered from A to I, and each sector is divided into four numbered sub-sectors.[60]

Sectors

Series A, B, and C are still underdeveloped. The D series has seven sectors (D-11 to D-17),[56] of which only sector D-12 is completely developed. This series is located at the foot of Margalla Hills.[59] The E Sectors are named from E-7 to E-17.[56] Many foreigners and diplomatic personnel are housed in these sectors.[59] In the revised Master Plan of the city, CDA has decided to develop a park on the pattern of Fatima Jinnah Park in sector E-14. Sectors E-8 and E-9 contain the campuses of Bahria University, Air University, and the National Defence University.[61][62][63] The F and G series contains the most developed sectors. F series contains sectors F-5 to F-17; some sectors are still under-developed.[56] F-5 is an important sector for the software industry in Islamabad, as the two software technology parks are located here. The entire F-9 sector is covered with Fatima Jinnah Park. The Centaurus complex is a major landmark of the F-8 sector.[59] G sectors are numbered G-5 through G-17.[56] Some important places include the Jinnah Convention Centre and Serena Hotel in G-5, the Red Mosque in G-6, the Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences, the largest medical complex in the capital, located in G-8,[59] and the Karachi Company shopping center in G-9.

The H sectors are numbered H-8 through H-17.[56] The H sectors are mostly dedicated to educational and health institutions. National University of Sciences and Technology covers a major portion of sector H-12.[59] The I sectors are numbered from I-8 to I-18. With the exception of I-8, which is a well-developed residential area, these sectors are primarily part of the industrial zone. Two sub-sectors of I-9 and one sub-sector of I-10 are used as industrial areas. CDA is planning to set up Islamabad Railway Station in Sector I-18 and Industrial City in sector I-17.[59] Zone III consists primarily of the Margalla Hills and Margalla Hills National Park. Rawal Lake is in this zone. Zone IV and V consist of Islamabad Park, and rural areas of the city. The Soan River flows into the city through Zone V.[56]

Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area

When the master plan for Islamabad was drawn up in 1960, Islamabad and Rawalpindi, along with the adjoining areas, was to be integrated to form a large metropolitan area called Islamabad/Rawalpindi Metropolitan Area. The area would consist of the developing Islamabad, the old colonial cantonment city of Rawalpindi, and Margalla Hills National Park, including surrounding rural areas.[64][65] However, Islamabad city is part of the Islamabad Capital Territory, while Rawalpindi is part of Rawalpindi District, which is part of province of Punjab.[66]

Initially, it was proposed that the three areas would be connected by four major highways: Murree Highway, Islamabad Highway, Soan Highway, and Capital Highway. However, to date only two highways have been constructed: Kashmir Highway (the former Murree Highway) and Islamabad Highway.[65] Plans of constructing Margalla Avenue are also underway.[67] Islamabad is the hub all the governmental activities while Rawalpindi is the centre of all industrial, commercial, and military activities. The two cities are considered sister cities and are highly interdependent.[64]

-

Aerial view of The Centaurus

-

Ufone Tower & ISE Tower

-

Star and Crescent Monument near the start of Shakarparian

-

Daman-e-Koh Park

-

Sunset over the Lake View Park

-

Night view of Blue Area, the commercial hub of the city.

-

Blue Area and Jinnah Avenue

-

New Blue Area Islamabad

Architecture

Islamabad's architecture is a combination of modernity and old Islamic and regional traditions. The Saudi-Pak Tower is an example of the integration of modern architecture with traditional styles. The beige-coloured edifice is trimmed with blue tile works in Islamic tradition, and is one of Islamabad's tallest buildings. Other examples of intertwined Islamic and modern architecture include Pakistan Monument and Faisal Mosque. Other notable structures are: Secretariat Complex designed by Gio Ponti, Prime Minister's secretariat based on Mughal architecture and the National Assembly by Edward Durell Stone.[29]

The murals on the inside of the large petals of Pakistan Monument are based on Islamic architecture.[68] The Shah Faisal Mosque is a fusion of contemporary architecture with a more traditional large triangular prayer hall and four minarets, designed by Vedat Dalokay, a Turkish architect and built with the help of funding provided by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia.[69] The architecture of Faisal Mosque is unusual as it lacks a dome structure. It is a combination of Arabic, Turkish, and Mughal architectural traditions.[70] The Centaurus is an example of modern architecture under construction in Islamabad. The seven star hotel was designed by WS Atkins PLC.The newly built Islamabad Stock Exchange Towers is another example of modern architecture in the city.[71]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 77,000 | — |

| 1981 | 204,000 | +164.9% |

| 1998 | 529,180 | +159.4% |

| 2017 | 1,009,003 | +90.7% |

| 2023 | 1,108,872 | +9.9% |

| Source: [72][73] | ||

Language

According to 2023 Pakistani census, There are 1,154,540 Punjabi, 415,838 Pashto, 358,922 Urdu, 140,780 Hindko, 51,920 Kashmiri, 46,270 Saraiki, 21,362 Sindhi, 10,315 Balti, 7,099 Shina, 5,016 Koshistani, 4,503 Balochi, 1,095 Mewati, 668 Brahvi, 182 Kalasha and 64,734 others, of total 2,283,244 speakers in Islamabad Capital Territory.

Literacy

The majority of the population lies in the age group of 15–64 years, around 59.38%. Only 2.73% of the population is above 65 years of age; 37.90% is below the age of 15.[75] Islamabad has the highest literacy rate in Pakistan, at 88%.[76] 9.8% of the population has done intermediate education (equivalent to grades 11 and 12). 10.26% have a bachelor or equivalent degree while 5.2% have a master or equivalent degree.[77] The labour force of Islamabad is 185,213[78] and the unemployment rate is 15.70%.[79]

Religion

Islam is the largest religion in the city, with 95.43% of the population following it. Christianity is the second largest religion is with 4.34% of the population following it. The Christians are concentrated mainly in the urban areas. Hinduism is followed by 0.04% of the population according to the 2017 census.[80][81][82]

Economy

Islamabad is a net contributor to the Pakistani economy, as whilst having only 0.8% of the country's population, it contributes 1% to the country's GDP.[83] Islamabad Stock Exchange, founded in 1989, is Pakistan's third largest stock exchange after Karachi Stock Exchange and Lahore Stock Exchange, and was merged to form Pakistan Stock Exchange. The exchange had 118 members with 104 corporate bodies and 18 individual members. The average daily turnover of the stock exchange is over 1 million shares.[84]

According to the World Bank's Doing Business Report of 2010, Islamabad was ranked as the best place to start a business in Pakistan.[85] Islamabad's businesses are Pakistan's most compliant for paying tax dues.[86] As of 2012[update], Islamabad LTU (Large Tax Unit) was responsible for Rs 371 billion in tax revenue, which amounts to 20% of all the revenue collected by Federal Board of Revenue.[87]

Islamabad has seen an expansion in information and communications technology with the addition two Software Technology Parks, which house numerous national and foreign technological and information technology companies. Awami Markaz IT Park houses 36 IT companies, while Evacuee Trust house 29 companies.[88] Islamabad will see its third IT Park by 2020, which will be built with assistance from South Korea.[89]

Culture

Islamabad is home to many migrants from other regions of Pakistan and has a cultural and religious diversity of considerable antiquity. Due to its location on the Pothohar Plateau, remnants of ancient cultures and civilisations such as Aryan, Soanian, and Indus Valley civilisation can still be found in the region. A 15th-century Gakhar fort, Pharwala Fort is located near Islamabad.[90][91] Rawat Fort in the region was built by the Gakhars in 16th century and contains the grave of the Gakhar chief, Sultan Sarang Khan.[91]

Saidpur village is supposedly named after Said Khan, the son of Sarang Khan. The 500-year-old village was converted into a place of Hindu worship by a Mughal commander, Raja Man Singh. He constructed a number of small ponds: Rama kunda, Sita kunda, Lakshaman kunda, and Hanuman kunda.[92] The region is home to a small Hindu temple that is preserved, showing the presence of Hindu people in the region. The shrine of Sufi mystic Pir Meher Ali Shah is located at Golra Sharif, which has a rich cultural heritage of the pre-Islamic period. Archaeological remains of the Buddhist era can also still be found in the region.[93] The shrine of Bari Imam was built by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. Thousands of devotees from across Pakistan attend the annual Urs of Bari Imam. The event is one of the largest religious gatherings in Islamabad. In 2004, the Urs was attended by more than 1.2 million people.[94]

The Lok Virsa Museum in Islamabad preserves a wide variety of expressions of folk and traditional cultural legacy of Pakistan. It is located near the Shakarparian hills and boasts a large display of embroidered costumes, jewellery, musical instruments, woodwork, utensils and folkloristic objects from the region and other parts of Pakistan.[95]

Tourism

Faisal Mosque is an important cultural landmark of the city and that attracts many tourists daily. Faisal Mosque built in 1986, was named after the Saudi Arabian King, Faisal bin Abdul Aziz.[96] It also serves the purpose of accommodating 24,000 Muslims that pray at this mosque. Faisal Mosque that is designed by the Turks and financed by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia includes calligraphy of Quranic verses along the walls of the mosque.

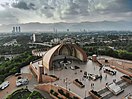

One of the landmarks for tourists is the Pakistan Monument built in 2007 located in Islamabad. This tourist attraction represents the patriotism and sovereignty of Pakistan. The design is shaped as a dome with petal-shaped walls that are engraved with arts portraying Pakistan's other tourist landmarks such as the Badshahi Mosque, Minar-e-Pakistan and Lahore Fort.[97]

Islamabad holds some of Pakistan's most prestigious museums such as Lok Virsa Museum, Institute of Folk and Traditional Heritage Shakarparian Park and prominent galleries such as the National Art Gallery and Gallery 6.

The Islamabad Museum contains many relics and artifacts dating back to the Gandhara period of the region, an intriguing fusion of Buddhist and Graeco-Roman styles. The living culture of Islamabad and Pakistan is best explored at Lok Virsa Museum, as well as the Institute of Folk and Traditional Heritage in Shakarparian Park.

Islamabad is built upon civilization and architecture that ranges from the 10th Century to the modern era. As Islamabad is situated on the Potohar Plateau, the remains of civilization descending from stone-age era include the Acheulian and the Soanian traditions and these are tourist landmarks. Islamabad has an array of historic landmarks that reflect the Hindu civilization that dates back to the 16th Century with examples such as Saidpur. Saidpur that is situated in Islamabad has progressed from a village to a sacred place that includes temples where the Hindu Mughal Commanders worshipped.[98]

Margalla Hills National Park is located in the North sector of Islamabad and is in close proximity to the Himalayas. The National Park includes of picturesque valleys and scenic hills that include various wildlife such as Himalayan goral, Barking deer and leopards. Flanked by wildlife and vegetation, Margalla Hills National Park also includes accommodation and camping grounds for tourists.

Education

Islamabad boasts the highest literacy rate in Pakistan at 98%,[76] and has some of the most advanced educational institutes in the country.[99] A large number of public and private sector educational institutes are present here. The higher education institutes in the capital are either federally chartered or administered by private organizations and almost all of them are recognised by the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan. High schools and colleges are either affiliated with the Federal Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education or with the UK universities education boards, O/A Levels, or IGCSE. According to the Academy of Educational Planning and Management's report, in 2009 there were a total of 913 recognized institutions in Islamabad (31 pre-primary, 2 religious, 367 primary, 162 middle, 250 high, 75 higher secondary and intermediate colleges, and 26 degree colleges).[100] There are seven teacher training institutes in Islamabad with a total enrolment of 604,633 students and 499 faculty.[100]

The Gender Parity Index in Islamabad is 0.93 compared to the 0.95 national average. There are 178 boys-only institutes, 175 girls-only, and 551 mixed institutes in Islamabad.[100] Total enrolment of students in all categories is 267,992; 138,272 for boys and 129,720 for girls.[100] There are 16 recognized universities in Islamabad with a total enrolment of 372,974 students and 30,144 teachers.[100] Most of the top ranked universities; National University of Sciences and Technology, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology and Pakistan Institute of Engineering & Applied Sciences, also have their headquarters in the capital.[16] The world's second largest general university by enrolment, Allama Iqbal Open University is located in Islamabad for distance education. Other universities include Air University, Bahria University, Center for Advanced Studies in Engineering, Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science and Technology, Hamdard University, National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Capital University of Science & Technology, National Defence University, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, National University of Modern Languages, Iqra University, International Islamic University, Virtual University of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah University, The University of Lahore, Abasyn University, and The Millennium University College.

Universities and colleges

- Abasyn University

- Air University

- Bahria University

- Center for Advanced Studies in Engineering

- COMSATS University Islamabad

- Foundation University

- Institute of Space Technology

- International Islamic University

- Mohammad Ali Jinnah University

- National Defence University

- National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences

- National University of Modern Languages

- NUST

- Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences

- Quaid-i-Azam University

- Riphah International University

- Roots Ivy College

- SZABIST

- University College of Islamabad

Healthcare

Islamabad has the lowest rate of infant mortality in the country at 38 deaths per thousand compared to the national average of 78 deaths per thousand.[101] Islamabad has both public and private medical centres. The largest hospital in Islamabad is Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS) hospital. It was established in 1985 as a teaching and doctor training institute. PIMS functions as a National Reference Center and provides specialised diagnostic and curative services.[102] The hospital has 30 major medical departments.[103] PIMS is divided into five administrative branches. Islamabad Hospital is the major component with a 592-bed facility and 22 medical and surgical specialties.[104]

The Children's Hospital is a 230-bed hospital completed in 1985. It contains six major facilities: Surgical and Allied Specialties, Medical and Allied Specialties, Diagnostic Facilities, Operation Theatre, Critical Care (NICU, PICU, Isolation & Accident Emergency), and a Blood Bank.[105] The Maternal and Child Health Care Center is a training institute with an attached hospital of 125 beds offering different clinical and operational services.[106] PIMS consists of five academic institutes: Quaid-e-Azam Postgraduate Medical College, College of Nursing, College of Medical Technology, School of Nursing, and Mother and Child Health Center.[107]

PAEC General Hospital and teaching institute, established in 2006, is affiliated with the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission.[108] The hospital consists of a 100-bed facility[108] and 10 major departments: Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pediatric, General Medicine, General Surgery, Intensive Care Unit/Coronary Care Unit, Orthopedics, Ophthalmology, Pathology, Radiology, and Dental Department.[109] Shifa International Hospital is a teaching hospital in Islamabad that was founded in 1987 and became a public company in 1989. The hospital has 70 qualified consultants in almost all specialties, 150 IPD beds and OPD facilities in 35 different specialisations.[110] According to the Federal Bureau of Statistics of the Government of Pakistan, in 2008 there were 12 hospitals, 76 dispensaries, and five maternity and child welfare centers in the city with a total of 5,158 beds.[111]

Transport

Aerial transport

Islamabad is connected to major destinations around the world and domestically through Islamabad International Airport (IIAP).[112] The airport is the largest in Pakistan and is located south-west of Islamabad. The new airport inaugurated on 20 April 2018, spreads over 19 square kilometers with 15 passenger boarding bridges. It also includes facilities to accommodate two double-decker Airbus A380s, 15 remote bays and 3 remote bays for Air cargo.[112]

Public transport

The Rawalpindi-Islamabad Metrobus is a 83.6 km (51.9 mi) bus rapid transit system operating in the Islamabad-Rawalpindi metropolitan area. The Metrobus network's first phase was opened on 4 June 2015, and stretches 22.5 kilometres between Pak Secretariat, in Islamabad, and Saddar in Rawalpindi. The second stage stretches 25.6 kilometres between the Peshawar Morr Interchange and New Islamabad International Airport and was inaugurated on 18 April 2022.[113][114] On 7 July 2022, the Green Line and Blue Lines were added to this Metrobus network.[115] The system uses e-ticketing and an Intelligent Transportation System and is managed by the Punjab Mass Transit Authority. The metro buses are widely used for commuting purposes by the labor force and students.

Railway

Islamabad railway station is located in sector I-9 in Islamabad, Capital Territory, Pakistan. The station appears as Margala on the Pakistan Railways website.[116]

Private transport

People use private transport like Taxis, Careem, Uber, Bykea, and SWVL for local journeys. In March 2016, Careem became functional in Islamabad and Rawalpindi with taxi services.

Roadways

M-2 Motorway is 367 km (228 mi) long and connect Islamabad and Lahore.[117] M-1 Motorway connects Islamabad with Peshawar and is 155 km (96 mi) long.[117] Islamabad is linked to Rawalpindi through the Faizabad Interchange, which has a daily traffic volume of about 48,000 vehicles.[118]

Sports

Islamabad has a multipurpose sports complex opposite Aabpara. It includes Liaquat Gymnasium for indoor games, Mushaf Squash Complex and Jinnah Sports Stadium for outdoor games, which is a venue for regular national and international events. 2004 SAF Games were held in the stadium. Some other sports venues of Islamabad include Diamond Club Ground, Shalimar Cricket Ground and Islamabad Golf Club.

There is another multipurpose sports complex in the F6 Markaz. It has tennis courts, a basketball court with fibre-glass boards and a Futsal ground which introduced artificial turf to the people of Islamabad.

Major sports in the city include cricket, football, squash, hockey, table tennis, rugby and boxing.[119] The city is home to Islamabad United[120] which won the first ever Pakistan Super League in 2016 and second title in 2018,[121][122] and Islamabad All Stars, which participates in the Super Kabaddi League.

Islamabad also has various rock climbing spots in the Margalla Hills.[123]

The Pakistan Sports Complex has three swimming pools for children. These facilities attract a large gathering on weekends.[124]

Recreation

Faisal Mosque

Located in Islamabad, Pakistan, the Faisal Mosque is the largest mosque in South Asia and the fourth largest mosque in the world. Built in the year 1986, it was named after the late king of Saudi Arabia, Faisal Bin Abdul Aziz, who backed and financed the construction.[125]

Trail 3

The most famous and oldest hiking track of Islamabad is Trail 3. It starts from the Margalla Road in sector F-6/3. Due to steep hills, the trail is exhausting to some extent. The course leads to the point where it goes up to the Viewpoint and is about a 30 – 50 minutes track. After the Viewpoint it continues for another easy-going 45 – 60 minutes and reaches the Pir Sohawa, where there are two restaurants for food, The Monal and La Montana. In total, it is approximately a one-hour and thirty minute walk.[126]

Pakistan Monument

Located in Islamabad, the Pakistan National Monument is a representation of the four provinces and three territories of the nation. Designed by the famous architect, Arif Masood, this blooming flower-shaped structure reflects the progress and prosperity of Pakistan.[127]

Shah Allah Ditta Caves

Shah Allah Ditta village is a centuries-old village and a Union Council of Islamabad Capital Authority. The village is named after a dervish that belonged to the Mughal era. It is estimated to be 650 years old approximately. It is also home to ancient caves that reflects the previous civilizations. The 2500-year-old Buddhist caves at the foot of Margalla Hills are located in west of Taxila, east of Islamabad and in the central area of Khanpur. A spring, a pond and a garden still exist near the Shah Allah Ditta Caves. There are some banyan trees in the garden, while all other fruit trees are gone. The water from the same spring was used to irrigate the garden adjoining the caves. During the Mughal period, when India was the centre of Sufism originating from Arabia and Central Asia, a saint named Shah Allah Ditta stayed in this garden and was entombed here. The place formerly attributed to sadhus, monks, or jogis is today known for the famous Sufi Shah Allah Ditta. A short distance from these caves is also an ancient baoli (stepwell) in the village of Kanthila, which is said to have been built by Sher Shah Suri.[128]

Twin towns and sister cities

See also

References

- ^ Administrator system was implemented for 6 months before next local bodies election and Deputy Commissioner, Islamabad was given additional charge as Administrator in absence of Mayor on 28 October 2021.[2]

- ^ McGarr, Paul (2013). The Cold War in South Asia: Britain, the United States and the Indian subcontinent, 1945-1965. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107008151. Archived from the original on 18 February 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ "Hamaza Shafqat appointed Administrator MCI for 6 months". The Nation (newspaper). 28 October 2021. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "College staff's winter vacation cancelled". Dawn (newspaper). 19 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "CDA Facts & Figures". Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Announcement of Results of 7th Population and Housing Census-2023" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (www.pbs.gov.pk). 5 August 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ "Islamabad". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021.

- ^ "History and Heritage". ICT Administration. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ "Islamabad, Pakistan Metro Area Population 1950-2023". www.macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ "Capital Development Authority". www.visitislamabad.net. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Leslie Noyes Mass (15 September 2011). Back to Pakistan: A Fifty-Year Journey. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 170. ISBN 978-1442213197.

- ^ Ravi Kalia (21 April 2011). Pakistan: From the Rhetoric of Democracy to the Rise of Militancy. Pakistan: Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 978-0415670401.

- ^ "National Monument: Structure reflects history of Pakistan – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 29 August 2013. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC - Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Hetland, Atle (23 March 2014). "Islamabad – a city only for the rich?". DAWN.COM. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ "G-12, a sector housing rich, poor alike". The Nation. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ a b HEC, Pakistan. "HEC University Rankings by Category". Archived from the original on 27 February 2012.

- ^ "Safe City Project gets operational: Islooites promised safety – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 6 June 2016. Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Crime rate in Islamabad drops, claim police". The Nation. 28 March 2015. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Adrian Room (13 December 2005). Placenames of the World. McFarland & Company. p. 177. ISBN 978-0786422487.

- ^ Capital Talk (6 February 2020). "Islamabad Ka Naam Kisney Rakha Tha, Qaum Be-Khabr Kyun?" [Who Named Islamabad, Why Is the Nation Unaware?]. YouTube (Video) (in Urdu). Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2020 – via Geo News.

- ^ "اسلام آباد: پاکستان کے وفاقی دارالحکومت کا نام کس نے اور کیسے تجویز کیا؟". BBC News اردو. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Islamabad history". Pakistan.net. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008.

- ^ a b Pakistan Defence Ministry. "Potohar". Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "Sacred rocks of Islamabad". Dawn. 2 August 2009. Archived from the original on 7 August 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ LEAD. "Background on the Potohar Plateau". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ^ "Saidpur Village – a witness to history". The Express Tribune. 27 March 2016. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Amjid, Iqbal (29 February 2016). "Taxila: Mughal-era coin & 'longest staircase' unearthed near Ban Faqiran". Daily Dawn News.

- ^ a b "New Orient". Czechoslovak Society for Eastern Studies. 4–6. Prague: 565. 1965. ISSN 0548-6408. OCLC 2264893.

- ^ a b Jonathan M. Bloom, ed. (23 March 2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0195309911.

- ^ "City of Islamabad". Capital Development Authority, Govt. of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Barbara A. Weightman (15 March 2011). Dragons and Tigers: A Geography of South, East, and Southeast Asia (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 187. ISBN 978-0470876282.

- ^ a b Wolfgang Saxon (11 April 1988). "New Capital City With an Industrial Twin". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ CDA Islamabad. "History of Islamabad". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016.

- ^ Maneesha Tikekar (1 January 2004). Across the Wagah: An Indian's Sojourn in Pakistan. Promilla. pp. 23–62. ISBN 978-8185002347.

- ^ a b "Islamabad". Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 May 2023. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ CDA Islamabad. "Islamabad Demographics". Archived from the original on 26 September 2009.

- ^ DAWN News (4 January 2004). "Islamabad making history". Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ^ "Quake's terrible toll is revealed". BBC News. 9 October 2005. Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ OhmyNews. "Timeline of Suicide Blasts in Islamabad". Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ Munawer Azeem (5 January 2012). "Islamabad saw four terror attacks last year". Dawn. Islamabad. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ A Reporter (28 January 2014). "Shahbaz to inaugurate work on Metro Bus Service on Feb 28". dawn.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Stanley D. Brunn; Jack F. Williams; Donald J. Zeigler (2003). "Cities of South Asia". Cities of the World: World Regional Urban Development (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 368–369. ISBN 978-0847698981.

- ^ "Islamabad Airport". Climate Charts. Archived from the original on 22 July 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ Yasmeen Niaz Mohiuddin (27 November 2006). Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook (1st ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 299. ISBN 978-1851098019. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Butt, M. J., Waqas, A., Iqbal, M, F., Muhammad., G., and Lodhi, M. A. K., 2011, "Assessment of Urban Sprawl of Islamabad Metropolitan Area Using Multi-Sensor and Multi-Temporal Satellite Data." Arabian Journal For Science And Engineering. Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1007/s13369-011-0148-3.

- ^ "Urban growth monitoring along Islamabad Highway". GIS Development. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "Climate Records: Islamabad". Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "Best Housing Societies in Islamabad to Invest in 2022". 13 June 2010. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ "Average Conditions, Islamabad, Pakistan". Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ^ "Margalla hills receive snowfall after decade". Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Severe Storms on dated 23rd July 2001 Islamabad, Pakistan" (PDF). Abdul Hameed, Director Pakistan Meteorological Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ "Weather Log – July 21–31, 2001". National Climatic Data Center. 6 August 2001. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ "Islamabad Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ "Islamabad Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Extremes of Islamabad". Pakistan Meteorological Department. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h DHA Lahore. "Map of Islamabad". Archived from the original on 14 February 2010.

- ^ Anis, Muhammad (2 March 2016). "70% CDA employees to be transferred to Islamabad Metropolitan Corporation". The Nation. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ CDA Official site. "CDA". Archived from the original on 5 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Idea of Islamabad". TheIslamabad.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ Matthew S. Hull (5 June 2012). Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan (1st ed.). University of California Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0520272156. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Bahria University. "Official website". Archived from the original on 1 March 2010.

- ^ Air University. "Official website". Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ National Defence University. "Official website". Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ a b Dulyapak Preecharushh (6 April 2011). "Myanmar's New Capital City of Naypyidaw". In Stanley D. Brunn (ed.). Engineering Earth: The Impacts of Megaengineering Projects (1st ed.). Springer. p. 1041. ISBN 978-9048199198.

- ^ a b Muhammad. "Planning of Islamabad and Rawalpindi" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ Sheikh, Iqbal M.; Van S. Williams; S. Qamer Raza; Kanwar S.A. Khan. "Environmental Geology of the Islamabad-Rawalpindi Area, Northern Pakistan" (PDF). Regional Studies of the Potwar Plateau Area, Northern Pakistan. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ "Margalla Avenue to benefit commuters of KPK, traffic on Kashmir Highway". OnePakistan. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ National Monument — a symbol of unity Archived 15 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Daily Times. 30 March. Retrieved 23 March 2008

- ^ Allison Lee Palmer (12 October 2009). The A to Z of Architecture. Scarecrow Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0810868953. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Archnet. "Faisal Mosque". Archived from the original on 3 May 2011.

- ^ Islamabad Stock Exchange-Official Website. "Islamabad Stock Exchange Towers". Archived from the original on 4 February 2005.

- ^ Elahi, Asad (2006). "2: Population". Pakistan Statistical Pocket Book 2006. Islamabad, Pakistan: Government of Pakistan: Statistics Division. p. 28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ DISTRICT WISE CENSUS RESULTS CENSUS 2017 (PDF) (Report). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 2017. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ "TABLE 11 – POPULATION BY MOTHER TONGUE, SEX AND RURAL/ URBAN" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Population Census Organization, Govt. of Pakistan. "POPULATION BY SELECTIVE AGE GROUPS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Literacy Rate" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ Population Census Organization, Govt. of Pakistan. "Population by Level of Education". Archived from the original on 20 July 2009.

- ^ Population Census Organization, Govt. of Pakistan. "LABOR FORCE PARTICIPATION RATES" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2010.

- ^ Population Census Organization, Govt. of Pakistan. "UN-EMPLOYMENT RATES" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2010.

- ^ Population Census Organization, Govt. of Pakistan. "POPULATION BY RELIGION" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2006.

- ^ "PML-Q opposes Hindu temple in Islamabad". Dawn. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "SALIENT FEATURES OF FINAL RESULTS CENSUS-2017" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "Pakistan | Economics and extremism". Dawn. 5 January 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ ISE-Official website. "About ISE". Archived from the original on 17 June 2011.

- ^ "Faisalabad best place to do business in Pakistan". The Express Tribune. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "Doing Business in Islamabad". Doing Business. Doing Business (World Bank). 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "Rs 371bn revenue target: FBR hails LTU Islamabad's performance". Business Recorder. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Pakistan Software Export Board. "Islamabad". Archived from the original on 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Islamabad to get IT Park by 2020". Express Tribune. 9 July 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ WikiMapia. "Pharwala Fort". Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ a b Ministry of Tourism, Government of Pakistan. "Forts of Pakistan". Archived from the original on 27 September 2009.

- ^ "Sidpur Village". The Daily Times. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ "Golra Sharif". Archived from the original on 11 August 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Huma Khawar. "Spotlight Bari Imam". Dawn News. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Viamigo. "RAWALPINDI/ISLAMABAD CITIES TOUR". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ "Shah Faisal Mosque: The Biggest Mosque in Pakistan | Urdu Pakistan". Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Let's Visit Pakistan National Monument and Museum in Islamabad Pakistan by Gulrukh Tausif | Traveler's Guide 360". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Charles S. Benson (1972). "New Cities and Educational Planning". In Dennis L. Roberts (ed.). Planning Urban Education: New Techniques to Transform Learning in the City. Educational Technology Publications. p. 111. ISBN 978-0877780243. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e AEPAM. "Pakistan Education Statistics 2008–09" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2013.

- ^ TheNews website. "Punjab tops in infant mortality, poverty, income inequality". Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ PIMS-Official website. "About PIMS". Archived from the original on 27 December 2005.

- ^ PIMS-Official website. "Departments at PIMS". Archived from the original on 28 February 2014.

- ^ PIMS-Official website. "Islamabad Hospital". Archived from the original on 27 December 2005.

- ^ PIMS-Official website. "Children Hospital". Archived from the original on 15 September 2009.

- ^ PIMS-Official website. "Maternal & Child Health Care Center". Archived from the original on 1 November 2005.

- ^ PIMS-Official website. "Quaid-i-Azam Postgraduate Medical College". Archived from the original on 15 July 2005.

- ^ a b PAEC General Hospital-Official website. "About PAEC Hospital". Archived from the original on 6 January 2009.

- ^ PAEC General Hospital-Official website. "Functions of Major Departments". Archived from the original on 6 January 2009.

- ^ SHIFA International Hospital-Official website. "SHIFA History". Archived from the original on 23 April 2009.

- ^ Federal Bureau of Statistics. "Hospitals/Dispensaries and Beds by Province" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2010.

- ^ a b Islamabad Airport. "Islamabad Airport". Islamabad Airport. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Islamabad Starts Trial of Orange Line Metro Bus Service". INCPAK. 16 April 2022. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "PM Shehbaz Sharif confident his 'speedy work' will frighten ex-premier Imran Khan". GEO News. 18 April 2022. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "PM Shahbaz inaugurates Green Line, Blue Line metro bus services". The News International. 7 July 2022. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Pakistan Railways". Pakistan Railways. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ a b National Highway Authority Pakistan. "Motorway's of Pakistan". Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- ^ NESPAK. "Faizabad Interchange". Archived from the original on 10 August 2011.

- ^ M. Hanif Raza (1985). Islamabad and environs. Colorpix. p. 83. ASIN B0006ENJ0I.

- ^ Shafique, Adnan. "Islamabad United". Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "ARY Digital Network President Salman Iqbal congratulates Islamabad United over winning PSL". arynews.tv. 24 February 2016. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ "Ronchi, Shadab seal Islamabad's second PSL title". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Arran, John (2012). "A Guide to Climbing in Margalla" (PDF). Rock Climbing Islamabad. Pakistan Alpine Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Sports facilities at Pakistan Sports Complex http://www.sports.gov.pk/SportsFacilities/sportsfacilities.htm#cycling Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Faisal Mosque Historical Facts and Pictures | The History Hub". www.thehistoryhub.com. 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ "Hiking Trail 3". Archived from the original on 11 July 2018.

- ^ "Pakistan National Monument Historical Facts and Pictures | The History Hub". www.thehistoryhub.com. 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ "Shah Allah Ditta caves – relic of ancient Buddhism". The Express Tribune. 9 June 2022. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Twin towns of Minsk". © 2008 The department of protocol and international relations of Minsk City Executive Committee. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Greater Amman Municipality-Official website. "Twin city agreements". Archived from the original on 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "The making of a slum city". The Express Tribune. 9 December 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "Islamabad to get new sister city". Dawn. 5 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Greater Municipality of Ankara. "Sister Cities of Ankara". Archived from the original on 5 July 2010.

- ^ Beijing International-Official website. "Sister cities". Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Daily Times". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ BeritaSatu.com. "KONI DKI Jalin Kerja Sama "Sister City" dengan 21 Kota Dunia". beritasatu.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Abbas, Zaffar, ed. (5 January 2016). "Islamabad to get new sister city". Dawn. Karachi, Pakistan: Pakistan Herald Publications.

- ^ "Islamabad declared sister city of Minsk". The Nation. 5 January 2016. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Fazal Sher – Daily Times. "Islamabad, Seoul to be made sister cities". Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

Further reading

- Moatasim, Faiza (2023). Master Plans and Encroachments: The Architecture of Informality in Islamabad. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-2519-0.

External links

Media related to Islamabad at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Islamabad at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Metropolitan Corporation Islamabad. Archived 17 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

Geographic data related to Islamabad at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Islamabad at OpenStreetMap