Babur

| Babur | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghazi[1] | |||||||||

Idealized portrait of Babur, early 17th century | |||||||||

| Mughal Emperor (Padishah) | |||||||||

| Reign | 21 April 1526 – 26 December 1530 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Ibrahim Lodhi (as Sultan of Delhi) | ||||||||

| Successor | Humayun | ||||||||

| Emir of Kabul | |||||||||

| Reign | October 1504[2] – 21 April 1526 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Mukin Begh | ||||||||

| Successor | Himself as the Mughal Emperor | ||||||||

| Emir of Fergana | |||||||||

| Reign | 10 June 1494 – February 1497 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Umar Shaikh Mirza II | ||||||||

| Successor | Jahangir Mirza II | ||||||||

| Emir of Samarkand | |||||||||

| Reign | November 1496 – February 1497 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Baysonqor Mirza | ||||||||

| Successor | Ali Mirza | ||||||||

| Born | 14 February 1483 Andijan, Timurid Empire | ||||||||

| Died | 26 December 1530 (aged 47) Agra, Mughal Empire | ||||||||

| Burial | Gardens of Babur, Kabul, Afghanistan | ||||||||

| Consort | |||||||||

| Wives more... | |||||||||

| Issue more... | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| House | House of Babur | ||||||||

| Dynasty | Timurid dynasty | ||||||||

| Father | Umar Shaikh Mirza II | ||||||||

| Mother | Qutlugh Nigar Khanum | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam[3] | ||||||||

| Seal |  | ||||||||

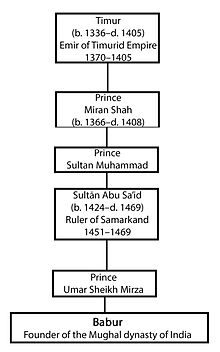

Babur (Persian: [βɑː.βuɾ]; 14 February 1483 – 26 December 1530; born Zahīr ud-Dīn Muhammad) was the founder of the Mughal Empire in the Indian subcontinent. He was a descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan through his father and mother respectively.[4][5][6] He was also given the posthumous name of Firdaws Makani ('Dwelling in Paradise').[7]

Born in Andijan in the Fergana Valley (now in Uzbekistan), Babur was the eldest son of Umar Shaikh Mirza II (1456–1494, governor of Fergana from 1469 to 1494) and a great-great-great-grandson of Timur (1336–1405). Babur ascended the throne of Fergana in its capital Akhsikath in 1494 at the age of twelve and faced rebellion. He conquered Samarkand two years later, only to lose Fergana soon after. In his attempt to reconquer Fergana, he lost control of Samarkand. In 1501, his attempt to recapture both the regions failed when the Uzbek prince Muhammad Shaybani defeated him and founded the Khanate of Bukhara.

In 1504, he conquered Kabul, which was under the putative rule of Abdur Razaq Mirza, the infant heir of Ulugh Beg II. Babur formed a partnership with the Safavid emperor Ismail I and reconquered parts of Turkestan, including Samarkand, only to again lose it and the other newly conquered lands to the Shaybanids.

After losing Samarkand for the third time, Babur turned his attention to India and employed aid from the neighbouring Safavid and Ottoman empires.[8] He defeated Ibrahim Lodi, the Sultan of Delhi, at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526 and founded the Mughal Empire. Before the defeat of Lodi at Delhi, the Sultanate of Delhi had been a spent force, long in a state of decline.

The rival adjacent Kingdom of Mewar under the rule of Rana Sanga had become the most powerful native power in North India.[9][10][11][12] Sanga unified several Rajput clans for the first time after Prithviraj Chauhan and advanced on Babur with a grand coalition of 80,000-100,000 Rajputs, engaging Babur in the Battle of Khanwa. Babur arrived at Khanwa with 40,000-50,000 soldiers. Nonetheless, Sanga suffered a major defeat due to Babur's skillful troop positioning and use of gunpowder, specifically matchlocks and small cannons.[13]

The Battle of Khanwa was one of the most decisive battles in Indian history, more so than the First Battle of Panipat, as the defeat of Rana Sanga was a watershed event in the Mughal conquest of North India.[14][15][16]

Religiously, Babur started his life as a staunch Sunni Muslim, but he underwent significant evolution. Babur became more tolerant as he conquered new territories and grew older, allowing other religions to peacefully coexist in his empire and at his court.[17] He also displayed a certain attraction to theology, poetry, geography, history, and biology—disciplines he promoted at his court—earning him a frequent association with representatives of the Timurid Renaissance.[18] His religious and philosophical stances are characterized as humanistic.[19]

Babur married several times. Notable among his children are Humayun, Kamran Mirza, Hindal Mirza, Masuma Sultan Begum, and the author Gulbadan Begum.

Babur died in 1530 in Agra and Humayun succeeded him. Babur was first buried in Agra but, as per his wishes, his remains were moved to Kabul and reburied.[20] He ranks as a national hero in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. Many of his poems have become popular folk songs. He wrote the Baburnama in Chaghatai Turkic; it was translated into Persian during the reign (1556–1605) of his grandson, the emperor Akbar.

Name

Ẓahīr-ud-Dīn is Arabic for "Defender of the Faith" (of Islam), and Muhammad honours the Islamic prophet. The name was chosen for Babur by the Sufi saint Khwaja Ahrar, who was the spiritual master of his father.[21] The difficulty of pronouncing the name for his Central Asian Turco-Mongol army may have been responsible for the greater popularity of his nickname Babur,[22] also variously spelled Baber,[23] Babar,[24] and Bābor.[5] The name is generally taken in reference to the Persian word babur (ببر), meaning "tiger" or "panther".[25][23][26] The word repeatedly appears in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and was borrowed into the Turkic languages of Central Asia.[24][27]

Background

Babur's memoirs form the main source for details of his life. They are known as the Baburnama and were written in Chagatai, his first language,[28] though, according to Dale, "his Turkic prose is highly Persianized in its sentence structure, morphology or word formation and vocabulary."[25] Baburnama was translated into Persian during the rule of Babur's grandson Akbar.[28]

Babur was born on 14 February 1483 in the city of Andijan, Fergana Valley, contemporary Uzbekistan. He was the eldest son of Umar Shaikh Mirza II,[29] ruler of the Fergana Valley, the son of Abū Saʿīd Mirza (and grandson of Miran Shah, who was himself son of Timur) and his wife Qutlugh Nigar Khanum, daughter of Yunus Khan, the ruler of Moghulistan (a descendant of Genghis Khan).[30]

Babur hailed from the Barlas tribe, which was of Mongol origin and had embraced the Turco-Persian tradition[31][32] They had also converted to Islam centuries earlier and resided in Turkestan and Khorasan.

Aside from the Chaghatai language, Babur was equally fluent in Classical Persian, the lingua franca of the Timurid elite.[33]

Some of Babur's relatives, such as his uncles Mahmud Khan (Moghul Khan) and Ahmad Khan, continued to identify as Mongols, and allowed him to use their Mongol troops to help recover his fortunes in the turbulent years that followed.[34]

Hence, Babur, though nominally a Mongol (or Moghul in Persian language), drew much of his support from the local Turkic and Iranian people of Central Asia, and his army was diverse in its ethnic makeup. It included Sarts, Tajiks, ethnic Afghans, Arabs, as well as Barlas and Chaghatayid Turko-Mongols from Central Asia.[35]

Ruler of Central Asia

As ruler of Fergana

In 1494, eleven-year-old Babur became the ruler of Fergana, in present-day Uzbekistan, after Umar Sheikh Mirza died "while tending pigeons in an ill-constructed dovecote that toppled into the ravine below the palace".[36] During this time, two of his uncles from the neighbouring kingdoms, who were hostile to his father, and a group of nobles who wanted his younger brother Jahangir to be the ruler, threatened his succession to the throne.[22] His uncles were relentless in their attempts to dislodge him from this position as well as from many of his other territorial possessions to come.[37] Babur was able to secure his throne mainly because of help from his maternal grandmother, Aisan Daulat Begum, although there was also some luck involved.[22]

Most territories around his kingdom were ruled by his relatives, who were descendants of either Timur or Genghis Khan, and were constantly in conflict.[22] At that time, rival princes were fighting over the city of Samarkand to the west, which was ruled by his paternal cousin.[38] Babur had a great ambition to capture the city.[38] In 1497, he besieged Samarkand for seven months before eventually gaining control over it.[39] He was fifteen years old and for him the campaign was a huge achievement.[22] Babur was able to hold the city despite desertions in his army, but he later fell seriously ill.[38] Meanwhile, a rebellion back home, approximately 350 kilometres (220 mi) away, amongst nobles who favoured his brother, robbed him of Fergana.[39] As he was marching to recover it, he lost Samarkand to a rival prince, leaving him with neither.[22] He had held Samarkand for 100 days, and he considered this defeat as his biggest loss, obsessing over it even later in his life after his conquests in India.[22]

For three years, Babur concentrated on building a strong army, recruiting widely amongst the Tajiks of Badakhshan in particular. In 1500–1501, he again laid siege to Samarkand, and indeed he took the city briefly, but he was in turn besieged by his most formidable rival, Muhammad Shaybani, Khan of the Uzbeks.[39][40] The situation became such that Babar was compelled to give his sister, Khanzada, to Shaybani in marriage as part of the peace settlement. Only after this were Babur and his troops allowed to depart the city in safety. Samarkand, his lifelong obsession, was thus lost again. He then tried to reclaim Fergana, but lost the battle there also and, escaping with a small band of followers, he wandered the mountains of central Asia and took refuge with hill tribes. By 1502, he had resigned all hopes of recovering Fergana; he was left with nothing and was forced to try his luck elsewhere.[41][42] He finally went to Tashkent, which was ruled by his maternal uncle, but he found himself less than welcome there. Babur wrote, "During my stay in Tashkent, I endured much poverty and humiliation. No country, or hope of one!"[42] Thus, during the ten years since becoming the ruler of Fergana, Babur suffered many short-lived victories and was without shelter and in exile, aided by friends and peasants.

At Kabul

Kabul was ruled by Babur's paternal uncle Ulugh Beg II, who died leaving only an infant as heir.[42] The city was then claimed by Mukin Begh, who was considered to be a usurper and was opposed by the local populace. In 1504, Babur was able to cross the snowy Hindu Kush mountains and capture Kabul from the remaining Arghunids, who were forced to retreat to Kandahar.[39] With this move, he gained a new kingdom, re-established his fortunes and would remain its ruler until 1526.[41] In 1505, because of the low revenue generated by his new mountain kingdom, Babur began his first expedition to India; in his memoirs, he wrote, "My desire for Hindustan had been constant. It was in the month of Shaban, the Sun being in Aquarius, that we rode out of Kabul for Hindustan". It was a brief raid across the Khyber Pass.[42]

In the same year, Babur united with Sultan Husayn Mirza Bayqarah of Herat, a fellow Timurid and distant relative, against their common enemy, the Uzbek Shaybani.[43] However, this venture did not take place because Husayn Mirza died in 1506 and his two sons were reluctant to go to war.[42] Babur instead stayed at Herat after being invited by the two Mirza brothers. It was then the cultural capital of the eastern Muslim world. Though he was disgusted by the vices and luxuries of the city,[44] he marvelled at the intellectual abundance there, which he stated was "filled with learned and matched men".[45] He became acquainted with the work of the Chagatai poet Mir Ali Shir Nava'i, who encouraged the use of Chagatai as a literary language. Nava'i's proficiency with the language, which he is credited with founding,[46] may have influenced Babur in his decision to use it for his memoirs. He spent two months there before being forced to leave because of diminishing resources;[43] it later was overrun by Shaybani and the Mirzas fled.[44] Babur became the only reigning ruler of the Timurid dynasty after the loss of Herat, and many princes sought refuge with him at Kabul because of Shaybani's invasion in the west.[44] He thus assumed the title of Padshah (emperor) among the Timurids—though this title was insignificant since most of his ancestral lands were taken, Kabul itself was in danger and Shaybani continued to be a threat.[44] Babur prevailed during a potential rebellion in Kabul, but two years later a revolt among some of his leading generals drove him out of Kabul. Escaping with very few companions, Babur soon returned to the city, capturing Kabul again and regaining the allegiance of the rebels. Meanwhile, Shaybani was defeated and killed by Ismail I, Shah of Shia Safavid Persia, in 1510.[47]

Babur and the remaining Timurids used this opportunity to reconquer their ancestral territories. Over the following few years, Babur and Shah Ismail formed a partnership in an attempt to take over parts of Central Asia. In return for Ismail's assistance, Babur permitted the Safavids to act as a suzerain over him and his followers.[48] Thus, in 1513, after leaving his brother Nasir Mirza to rule Kabul, he managed to take Samarkand for the third time; he also took Bokhara but lost both again to the Uzbeks.[41][44] Shah Ismail reunited Babur with his sister Khānzāda, who had been imprisoned by and forced to marry the recently deceased Shaybani.[49] Babur returned to Kabul after three years in 1514. The following 11 years of his rule mainly involved dealing with relatively insignificant rebellions from Afghan tribes, his nobles and relatives, in addition to conducting raids across the eastern mountains.[44] Babur began to modernise and train his army despite it being, for him, relatively peaceful times.[50]

Foreign relations

Determined to conquer the Uzbeks and recapture his ancestral homeland, Babur was wary of their allies the Ottomans, and made no attempt to establish formal diplomatic relations with them. He did, however, employ the matchlock commander Mustafa Rumi and several other Ottomans.[51] From them, he adopted the tactic of using matchlocks and cannons in the field (rather than only in sieges), which gave him an important advantage in India.[50]

Formation of the Mughal Empire

Babur still wanted to escape from the Uzbeks, and he chose India as a refuge instead of Badakhshan, which was to the north of Kabul. He wrote, "In the presence of such power and potency, we had to think of some place for ourselves and, at this crisis and in the crack of time there was, put a wider space between us and the strong foeman."[50] After his third loss of Samarkand, Babur gave full attention to the conquest of North India, launching a campaign; he reached the Chenab River, now in Pakistan, in 1519.[41] Until 1524, his aim was to only expand his rule to Punjab, mainly to fulfill the legacy of his ancestor Timur, since it used to be part of his empire.[50] At the time parts of North India were part of the Delhi Sultanate, ruled by Ibrahim Lodi of the Lodi dynasty, but the sultanate was crumbling and there were many defectors. Babur received invitations from Daulat Khan Lodi, Governor of Punjab and Ala-ud-Din, uncle of Ibrahim.[52] He sent an ambassador to Ibrahim, claiming himself the rightful heir to the throne, but the ambassador was detained at Lahore, Punjab, and released months later.[41]

Babur started for Lahore in 1524 but found that Daulat Khan Lodi had been driven out by forces sent by Ibrahim Lodi.[53] When Babur arrived at Lahore, the Lodi army marched out and his army was routed. In response, Babur burned Lahore for two days, then marched to Dibalpur, placing Alam Khan, another rebel uncle of Lodi, as governor.[54] Alam Khan was quickly overthrown and fled to Kabul. In response, Babur supplied Alam Khan with troops who later joined up with Daulat Khan Lodi, and together with about 30,000 troops, they besieged Ibrahim Lodi at Delhi.[55] The sultan easily defeated and drove off Alam's army, and Babur realised that he would not allow him to occupy the Punjab.[55]

First Battle of Panipat

In November 1525 Babur got news at Peshawar that Daulat Khan Lodi had switched sides, and Babur drove out Ala-ud-Din. Babur then marched onto Lahore to confront Daulat Khan Lodi, only to see Daulat's army melt away at their approach.[41] Daulat surrendered and was pardoned. Thus within three weeks of crossing the Indus River Babur had become the master of Punjab.[56]

Babur marched on to Delhi via Sirhind. He reached Panipat on 20 April 1526 and there met Ibrahim Lodi's numerically superior army of about 100,000 soldiers and 100 elephants.[41][52] In the battle that began on the following day, Babur used the tactic of Tulugma, encircling Ibrahim Lodi's army and forcing it to face artillery fire directly, as well as frightening its war elephants.[52] Ibrahim Lodi died during the battle, thus ending the Lodi dynasty.[41]

Babur wrote in his memoirs about his victory:

By the grace of the Almighty God, this difficult task was made easy to me and that mighty army, in the space of a half a day was laid in dust.[41]

After the battle, Babur occupied Delhi and Agra, took the throne of Lodi, and laid the foundation for the eventual rise of Mughal rule in India. However, before he became North India's ruler, he had to fend off challengers, such as Rana Sanga.[57]

Many of Babur's men allegedly wanted to leave India due to its warm climate, but Babur motivated them to stay and expand his empire.[citation needed]

Battle of Khanwa

The Battle of Khanwa was fought between Babur and the Rajput ruler of Mewar, Rana Sanga on 16 March 1527. Rana Sanga wanted to overthrow Babur, whom he considered to be a foreigner ruling in India, and also to extend the Rajput territories by annexing Delhi and Agra. He was supported by Afghan chiefs who felt Babur had been deceptive by refusing to fulfil promises made to them. Upon receiving news of Rana Sangha's advance towards Agra, Babur took a defensive position at Khanwa (currently in the Indian state of Rajasthan), from where he hoped to launch a counterattack later. According to K.V. Krishna Rao, Babur won the battle because of his "superior generalship" and modern tactics; the battle was one of the first in India that featured cannons and muskets. Rao also notes that Rana Sanga faced "treachery" when the Hindu chief Silhadi joined Babur's army with a garrison of 6,000 soldiers.[59]

Babur recognised Sanga's skill in leadership, calling him one of the two greatest non-Muslim Indian kings of the time, the other being Krishnadevaraya of Vijayanagara.[60]

Battle of Chanderi

The Battle of Chanderi took place the year after the Battle of Khanwa. On receiving news that Rana Sanga had made preparations to renew the conflict with him, Babur decided to isolate the Rana by defeating one of his staunchest allies, Medini Rai, who was the ruler of Malwa.[61][62]

Upon reaching Chanderi, on 20 January 1528,[61] Babur offered Shamsabad to Medini Rao in exchange for Chanderi as a peace overture, but the offer was rejected.[62] The outer fortress of Chanderi was taken by Babur's army at night, and the next morning the upper fort was captured. Babur himself expressed surprise that the upper fort had fallen within an hour of the final assault.[61] Seeing no hope of victory, Medini Rai organized a jauhar, during which women and children within the fortress immolated themselves.[61][62] A small number of soldiers also collected in Medini Rao's house and killed each other in collective suicide. This sacrifice does not seem to have impressed Babur, who did not express a word of admiration for the enemy in his autobiography.[61]

Religious policy

Babur defeated and killed Ibrahim Lodi, the last Sultan of the Lodi dynasty, in 1526. Babur ruled for 4 years and was succeeded by his son Humayun whose reign was temporarily usurped by the Suri dynasty. During their 30-year rule, religious violence continued in India. Records of the violence and trauma, from Sikh-Muslim perspective, include those recorded in Sikh literature of the 16th century.[63] The violence of Babur in the 1520s was witnessed by Guru Nanak, who commented upon it in four hymns.[citation needed] Historians suggest the early Mughal period of religious violence contributed to introspection and then the transformation in Sikhism from pacifism to militancy for self-defense.[63] According to Babur's autobiography, Baburnama, his campaign in northwest India targeted Hindus and Sikhs as well as apostates (non-Sunni sects of Islam), and an immense number were killed, with Muslim camps building "towers of skulls of the infidels" on hillocks.[64] In Babur's secret will, in the year 935AH, 1529 AD, to Humayun, Babur adivses Humayun to administer justice according to the ways of every religion, avoid sacrifice of the cow, not to ruin the temples and shrines of any law obeying community, overlook the dissensions of the Shias and the Sunnis.[65]

Personal life and relationships

There are no descriptions about Babur's physical appearance, except from the paintings in the translation of the Baburnama prepared during the reign of Akbar.[42] In his autobiography, Babur claimed to be strong and physically fit, and that he had swum across every major river he encountered, including twice across the Ganges River in North India.[66]

Babur did not initially know Old Hindi; however, his Turkic poetry indicates that he picked up some of its vocabulary later in life.[67]

Unlike his father, he had ascetic tendencies and did not have any great interest in women. In his first marriage, he was "bashful" towards Aisha Sultan Begum, later losing his affection for her.[68] Babur showed similar shyness in his interactions with Baburi, a boy in his camp with whom he had an infatuation around this time, recounting that:

"Occasionally Baburi came to me, but I was so bashful that I could not look him in the face, much less converse freely with him. In my excitement and agitation I could not thank him for coming, much less complain of his leaving. Who could bear to demand the ceremonies of fealty?"[69][70]

However, Babur acquired several more wives and concubines over the years, and as required for a prince, he was able to ensure the continuity of his line.

Babur's first wife, Aisha Sultan Begum, was his paternal cousin, the daughter of Sultan Ahmad Mirza, his father's brother. She was an infant when betrothed to Babur, who was himself five years old. They married eleven years later, c. 1498–99. The couple had one daughter, Fakhr-un-Nissa, who died within a year in 1500. Three years later, after Babur's first defeat at Fergana, Aisha left him and returned to her father's household.[71][50] In 1504, Babur married Zaynab Sultan Begum, who died childless within two years. In the period 1506–08, Babur married four women, Maham Begum (in 1506), Masuma Sultan Begum, Gulrukh Begum and Dildar Begum.[71] Babur had four children by Maham Begum, of whom only one survived infancy. This was his eldest son and heir, Humayun. Masuma Sultan Begum died during childbirth; the year of her death is disputed (either 1508 or 1519). Gulrukh bore Babur two sons, Kamran and Askari, and Dildar Begum was the mother of Babur's youngest son, Hindal.[71] Babur later married Mubaraka Yusufzai, a Pashtun woman of the Yusufzai tribe. Gulnar Aghacha and Nargul Aghacha were two Circassian slaves given to Babur as gifts by Tahmasp Shah Safavi, the Shah of Persia. They became "recognized ladies of the royal household."[71]

During his rule in Kabul, when there was a time of relative peace, Babur pursued his interests in literature, art, music and gardening.[50] Previously, he never drank alcohol and avoided it when he was in Herat. In Kabul, he first tasted it at the age of thirty. He then began to drink regularly, host wine parties and consume preparations made from opium.[44] Though religion had a central place in his life, Babur also approvingly quoted a line of poetry by one of his contemporaries: "I am drunk, officer. Punish me when I am sober". He quit drinking for health reasons before the Battle of Khanwa, just two years before his death, and demanded that his court do the same. But he did not stop chewing narcotic preparations, and did not lose his sense of irony. He wrote, "Everyone regrets drinking and swears an oath (of abstinence); I swore the oath and regret that."[72]

Babur was opposed to the blind obedience towards the Chinggisid laws and customs that were influential in Turco-Mongol society:

"Previously our ancestors had shown unusual respect for the Chingizid code (törah). They did not violate this code sitting and rising at councils and court, at feasts and dinners. [However] Chingez Khan's code is not a nass qati (categorical text) that a person must follow. Whenever one leaves a good custom, it should be followed. If ancestors leave a bad custom, however it is necessary to substitute a good one."

Making clear that to him, the categorical text (i.e. the Quran) had displaced Genghis Khan's Yassa in moral and legal matters.[73]

Poetry

Babur was an acclaimed writer, who had a profound love for literature. His library was one of his most beloved possessions that he always carried around with him, and books were one of the treasures he searched for in new conquered lands. In his memoirs, when he listed sovereigns and nobles of a conquered land, he also mentioned poets, musicians and other educated people.[74]

During his 47-year life, Babur left a rich literary and scientific heritage. He authored his famous memoir the Bāburnāma, as well as beautiful lyrical works or ghazals, treatises on Muslim jurisprudence (Mubayyin), poetics (Aruz risolasi), music, and a special calligraphy, known as khatt-i Baburi.[75][76][77][78]

Babur's Bāburnāma is a collection of memoirs, written in the Chagatai language and later translated into Persian, the usual literary language of the Mughal court, during the rule of emperor Akbar.[79] However, Babur's Turkic prose in Bāburnāma is already highly Persianized in its sentence structure, vocabulary, and morphology,[80] and also consists of several phrases and minor poems in Persian.

Babur wrote most of his poems in Chagatai Turkic, known to him as Türki, but he also composed in Persian. However, he was mostly praised for his literary works written in Turkic, which drew comparison with the poetry of Ali-Shir Nava'i.[74]

The following ruba'i is an example of Babur's poetry written in Turkic, composed in the aftermath of his famous victory in North India to celebrate his ghazi status.[81]

|

Islam ichin avara-i yazi buldim, |

I am become a desert wanderer for Islam,

|

Family

Consorts

- Aisha Sultan Begum (m. 1499; div. 1503), daughter of Sultan Ahmed Mirza — First wife of Babur

- Zainab Sultan Begum (m. 1504; d. 1506–07), daughter of Sultan Mahmud Mirza

- Maham Begum (m. 1506) — Babur's chief and favourite consort

- Masuma Sultan Begum (m. 1507; d. 1508), daughter of Sultan Ahmed Mirza and half-sister of Aisha Sultan Begum

- Bibi Mubarika (m. 1519), Pashtun of the Yusufzai tribe

- Gulrukh Begum (not to be confused with Babur's daughter Gulrukh Begum, who was also known as Gulbarg Begum)

- Dildar Begum

- Gulnar Aghacha, Circassian concubine

- Nargul Aghacha, Circassian concubine

The identity of the mother of one of Babur's daughters, Gulrukh Begum is disputed. Gulrukh's mother may have been the daughter of Sultan Mahmud Mirza by his wife Pasha Begum who is referred to as Saliha Sultan Begum in certain secondary sources, however this name is not mentioned in the Baburnama or the works of Gulbadan Begum, which casts doubt on her existence. This woman may never have existed at all or she may even be the same woman as Dildar Begum.

Issue

The sons of Babur were:

- Humayun (b. 1508; d. 1556) — with Maham Begum — succeeded Babur as the second Mughal Emperor

- Kamran Mirza (b. 1512; d. 1557) — with Gulrukh Begum

- Askari Mirza (b. 1518; d. 1557) — with Gulrukh Begum

- Hindal Mirza (b. 1519; d. 1551) — with Dildar Begum

- Ahmad Mirza (d. young) — with Gulrukh Begum

- Shahrukh Mirza (d. young) — with Gulrukh Begum

- Barbul Mirza (d. infancy) — with Maham Begum

- Alwar Mirza (d. young) — with Dildar Begum

- Faruq Mirza (d. infancy) — with Maham Begum

The daughters of Babur were:

- Fakhr-un-Nissa Begum (b. & d. 1501) — with Aisha Sultan Begum

- Aisan Daulat Begum (d. infancy) — with Maham Begum

- Mehr Jahan Begum (d. infancy) — with Maham Begum

- Masuma Sultan Begum (b. 1508) — with Masuma Sultan Begum — Married to Muhammad Zaman Mirza.

- Gulzar Begum (d. infancy) — with Gulrukh Begum

- Gulrukh Begum (Gulbarg Begum) — Identity of mother is disputed, may have been Dildar Begum or Saliha Sultan Begum — Married to Nuruddin Muhammad Mirza, son of Khwaja Hasan Naqshbandi, with whom she had Salima Sultan Begum, wife of Bairam Khan and later the Mughal Emperor Akbar.

- Gulbadan Begum (b. c. 1523 – d. 1603) — with Dildar Begum — Married Khizr Khwaja Khan, son of her father's cousin Aiman Khwajah Sultan of Moghulistan, son of Ahmad Alaq of Moghulistan, the maternal uncle of Emperor Babur.

- Gulchehra Begum (b. c. 1515 – d. 1557) — with Dildar Begum — Married firstly in 1530 to Sultan Tukhta Bugha Khan, son of Ahmad Alaq of Moghulistan, the maternal uncle of Emperor Babur. Married secondly to Abbas Sultan Uzbeg.

- Gulrang Begum — with Dildar Begum — Married in 1530 to Isan Timur Sultan, ninth son of Ahmad Alaq of Moghulistan, the maternal uncle of Emperor Babur.

Death and legacy

Babur died in Agra at the age of 47 on 5 January [O.S. 26 December 1530] 1531 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Humayun. He was first buried in Chauburji, Agra.[82][83] Later as per his wishes, his mortal remains were moved to Kabul and reburied in Bagh-e Babur in Kabul sometime between 1539 and 1544.[20][57]

It is generally agreed that, as a Timurid, Babur was not only significantly influenced by the Persian culture, but also that his empire gave rise to the expansion of the Persianate ethos in the Indian subcontinent.[5][6] He emerged in his own telling as a Timurid Renaissance inheritor, leaving signs of Islamic, artistic literary, and social aspects in India.[84][85]

For example, F. Lehmann states in the Encyclopædia Iranica:

His origin, milieu, training, and culture were steeped in Persian culture and so Babur was largely responsible for the fostering of this culture by his descendants, the Mughals of India, and for the expansion of Persian cultural influence in the Indian subcontinent, with brilliant literary, artistic, and historiographical results.[32]

Although all applications of modern Central Asian ethnicities to people of Babur's time are anachronistic, Soviet and Uzbek sources regard Babur as an ethnic Uzbek.[86][87][88] At the same time, during the Soviet Union Uzbek scholars were censored for idealising and praising Babur and other historical figures such as Ali-Shir Nava'i.[89]

Babur is considered a national hero in Uzbekistan.[90] On 14 February 2008, stamps in his name were issued in the country to commemorate his 525th birth anniversary.[91] Many of Babur's poems have become popular Uzbek folk songs, especially by Sherali Joʻrayev.[92] Some sources claim that Babur is a national hero in Kyrgyzstan too.[93] In October 2005, Pakistan developed the Babur Cruise Missile, named in his honour.

Shahenshah Babar, an Indian film about the emperor directed by Wajahat Mirza was released in 1944. The 1960 Indian biographical film Babar by Hemen Gupta covered the emperor's life with Gajanan Jagirdar in the lead role.[94]

One of the enduring features of Babur's life was that he left behind the lively and well-written autobiography known as Baburnama.[95] Quoting Henry Beveridge, Stanley Lane-Poole writes:

His autobiography is one of those priceless records which are for all time, and is fit to rank with the confessions of St. Augustine and Rousseau, and the memoirs of Gibbon and Newton. In Asia it stands almost alone.

[96] In his own words, "The cream of my testimony is this, do nothing against your brothers even though they may deserve it." Also, "The new year, the spring, the wine and the beloved are joyful. Babur make merry, for the world will not be there for you a second time."[97]

Babri Masjid

The Babri Masjid ("Babur's Mosque") in Ayodhya, was constructed by Mir Baqi (commander of the Babur), according to the mosque's inscriptions, in 1528–29 (935 AH). On 6 December 1992, Babri Masjid was demolished by a large group of activists of the Vishva Hindu Parishad and allied organisations.

In 2003 the Allahabad High Court ordered the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to conduct a more in-depth study and an excavation to ascertain the type of structure beneath the mosque.[98] The excavation was conducted from 12 March 2003 to 7 August 2003, resulting in 1360 discoveries.[99]

The summary of the ASI report indicated the presence of a 10th-century temple under the mosque.[100][101] The ASI team said that, human activity at the site dates back to the 13th century BCE. The next few layers date back to the Shunga period (second-first century BCE) and the Kushan period. During the early medieval period (11–12th century CE), a huge but short-lived structure of nearly 50 metres north–south orientation was constructed. On the remains of this structure, another massive structure was constructed: this structure had at least three structural phases and three successive floors attached with it. The report concluded that it was over the top of this construction that the disputed structure was constructed during the early 16th century.[102] Archaeologist KK Muhammed, the only Muslim member in the team of people surveying the excavation, also confirmed individually that there existed a temple like structure before the Babri Masjid was constructed over it.[103]

Several archaeologists disputed ASI findings.[104] According to archaeologist Supriya Verma and Jaya Menon, who observed the excavations on behalf of the Sunni Waqf Board, "the ASI was operating with a preconceived notion of discovering the remains of a temple beneath the demolished mosque, even selectively altering the evidence to suit its hypothesis." this allegation particularly focused on the "pillar bases" central to the claim of a temple, which Verma and Menon alleged were irregularly shaped, irregularly spaced and largely the result of selective excavation, rather than representing genuine evidence of pillars.[105]

The Supreme Court judgement of 2019 granted the entire disputed land to the Hindus for construction of a temple, stating that Hindus continue to worship at the site and continued to hold the land outside the yard. It also held that there is nothing to prove that the structure, which was present before the construction of the mosque, was demolished for the purpose of building mosque or was already in ruins.[106][107]

Citations

- ^ Dale, Stephen F. (2018). Babur. p. 154.

- ^ Avali, Raghu (17 December 2023). "The Conquest of Kabul (1504)". Indian History for Everyone. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Christine, Isom-Verhaaren (2013). Allies with the Infidel. I.B. Tauris. p. 58.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (2018). The History of Central Asia: The Age of Islam and the Mongols. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 47.

- ^ a b c "Ẓahīr-al-Dīn Moḥammad Bābor" at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ a b Canfield, Robert L. (1991). Turko-Persia in historical perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 20.

The Mughals-Persianized Turks who invaded from Central Asia and claimed descent from both Timur and Genghis – strengthened the Persianate culture of Muslim India.

- ^ Jahangir, Emperor Of Hindustan (1999). The Jahangirnama : memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Thackston, W. M. Washington, D.C. : Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution ; New York : Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Gilbert, Marc Jason (2017), South Asia in World History, Oxford University Press, pp. 75–, ISBN 978-0-19-066137-3, archived from the original on 22 September 2023, retrieved 11 June 2021 Quote: "Babur then adroitly gave the Ottomans his promise not to attack them in return for their military aid, which he received in the form of the newest of battlefield inventions, the matchlock gun and cast cannons, as well as instructors to train his men to use them."

- ^ Bhatnagar, V. S. (1974). Life and Times of Sawai Jai Singh, 1688–1743. Impex India. p. 6.

From 1326, Mewar's grand recovery commenced under Lakha, and later under Kumbha and most notably under Sanga, till it became one of the greatest powers in northern India during the first quarter of sixteenth century.

- ^ Sarda, Har Bilas (1918). Maharana Sanga; the Hindupat, the last great leader of the Rajput race. University of California Libraries. Ajmer, Scottish Mission Industries. pp. 01–03.

Babur, the founder of the Turk power in India, says in his Memoirs that Rana Sanga was the most powerful sovereign in Hindustan when he invaded it, and that he attained his present high eminence by his own valour and sword. Eighty thousand horse, 7 Rajas of the highest rank, 9 Raos and 104 chieftains bearing the titles of Rawal and Rawat, with 500 war elephants, followed him into the field. The princes of Marwar and Amber (Jodhpur and Jaipur) did him homage, and the Raos of Gwalior, Ajmer, Sikri, Raisen, Kalpi, Chanderi, Boondi, Gagroon, Rampura and Abu served him as tributaries or held of him in chief.

- ^ Sharma, G. N. (1954). Mewar and the mughal emperors. pp. 8–45.

Before describing his early power, it is worthwhile to say a word or two concerning the personality and the previous history of the man (Rana Sanga) who was destined to be the acknowledged leader of Hindu India of the first half of the 16th century.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2005). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals Part - II. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 25–40. ISBN 978-81-241-1066-9.

- ^ Dale, Stephen F. (3 May 2018). Babur. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-47007-0.

- ^ Majumdar, R.C.; Raychaudhuri, H.C.; Datta, Kalikinkar (1950). An Advanced History of India (2nd ed.). Macmillan & Company. p. 419.

The battle of khanua was one of the most decisive battles in Indian history certainly more than that of Panipat as Lodhi empire was already crumbling and Mewar had emerged as major power in northern India. Thus, Its at Khanua the fate of India was sealed for next two centuries

- ^ Chaurasia, Radheyshyam (2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 161. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4.

The battle of Kanwaha was more important in its result even than the first battle of panipat. While the former made Babur ruler of Delhi alone the later made him King of hindustan. As a result of his success, the Mughal empire was established firmly in India. The sovereignty of India now passed from Rajputs to Mughals

- ^ Wink 2012, p. 27: "The victory of Mughals at khanua can be seen as a landmark event in Mughal conquest of North India as the battle turned out to be more historic and eventful than one fought near Panipat. It made Babur undisputed master of North India while smashing Rajput powers. After the victory at khanua, the centre of Mughal power became Agra instead of Kabul and continue to remain till downfall of the Empire after Aalamgir's death.

- ^ Hamès, Constant (1987). "Babur Le Livre de Babur". Archives de sciences sociales des religions. 63 (2): 222–223. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Babur; Bacqué-Grammont, Jean-Louis; Taha Hussein-Okada, Amina (2022). Le livre de Babur: le Babur-nama de Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur. Série indienne. Paris: les Belles lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-45370-5.

- ^ Dale, Stephen Frederic (1990). "Steppe Humanism: The Autobiographical Writings of Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur, 1483–1530". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 22 (1): 37–58. doi:10.1017/S0020743800033171. ISSN 0020-7438. S2CID 161867251.

- ^ a b Necipoğlu, Gülru (1997), Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, Brill, p. 135, ISBN 90-04-10872-6, archived from the original on 5 February 2024, retrieved 8 February 2019

- ^ Noshahi, Arif (2005). خواجہ احرار. Lahore, Pakistan: پورب اکیڈمی.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eraly 2007, pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b EB (1878).

- ^ a b EB (1911).

- ^ a b Dale, Stephen Frederic (2004). The garden of the eight paradises: Bābur and the culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483–1530). Brill. pp. 15, 150. ISBN 90-04-13707-6.

- ^ Babur; Bacqué-Grammont, Jean-Louis; Taha Hussein-Okada, Amina (2022). Le livre de Babur: le Babur-nama de Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur. Série indienne. Paris: les Belles lettres. p. 3. ISBN 978-2-251-45370-5.

- ^ Thumb, Albert, Handbuch des Sanskrit, mit Texten und Glossar, German original, ed. C. Winter, 1953, Snippet, p. 318 Archived 27 November 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Hiro, Dilip (2006). Babur Nama: Journal of Emperor Babur. Mumbai: Penguin Books India. p. xviii. ISBN 978-0-14-400149-1.

- ^ "Mirza Muhammad Haidar". Silk Road Seattle. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

On the occasion of the birth of Babar Padishah (the son of Omar Shaikh)

- ^ Babur (2006). Babur Nama. Penguin Books. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-14-400149-1.

- ^ "Bābur (Mughal emperor)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ a b Lehmann, F. "Memoirs of Zehīr-ed-Dīn Muhammed Bābur". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ "Iran: The Timurids and Turkmen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 June 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Dale, Stephen F. (2018). Babur:Timurid Prince and Mughal Emperor, 1483-1530. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9781316996379.

- ^ Manz, Beatrice Forbes (1994). "The Symbiosis of Turk and Tajik". Central Asia in Historical Perspective. Boulder, Colorado & Oxford. p. 58. ISBN 0-8133-3638-4.

- ^ "Babur, the first Moghul emperor: Wine and tulips in Kabul". The Economist. 16 December 2010. pp. 80–82. Archived from the original on 15 January 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Lal, Ruby (2005). Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World. Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-521-85022-3.

It was over these possessions, provinces controlled by uncles, or cousins of varying degrees, that Babur fought with close and distant relatives for much of his life.

- ^ a b c Eraly 2007, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d Ewans, Martin (2002). Afghanistan: A Short History of Its People and Politics. HarperCollins. pp. 26–27. ISBN 0-06-050508-7.

Babur, while still in his teens, conceived the ambition of conquering Samarkand. In 1497, after a seven months' siege, he took the city, but his supporters gradually deserted him and Ferghana was taken from him in his absence. Within a few months he was compelled to retire from Samarkand ... Eventually he retook Samarkand, but was again forced out, this time by an Usbek leader, Shaibani Khan ... Babur decided in 1504 to trek over the Hindu Kush to Kabul, where the current ruler promptly retreated to Kandahar and left him in undisputed control of the city.

- ^ "The Memoirs of Babur". Silk Road Seattle. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2006.

After being driven out of Samarkand in 1501 by the Uzbek Shaibanids ...

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mahajan, V.D. (2007). History of medieval India (10th ed.). New Delhi: S Chand. pp. 428–29. ISBN 978-81-219-0364-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Eraly 2007, pp. 21–23.

- ^ a b Brend, Barbara (2002). Perspectives on Persian Painting: Illustrations to Amir Khusrau's Khamsah. Routledge (UK). p. 188. ISBN 0-7007-1467-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eraly 2007, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Lamb, Christina (2004). The Sewing Circles of Herat: A Personal Voyage Through Afghanistan. HarperCollins. p. 153. ISBN 0-06-050527-3.

- ^ Hickmann, William C. (1992). Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. Princeton University Press. p. 473. ISBN 0-691-01078-1.

Eastern Turk Mir Ali Shir Neva'i (1441–1501), founder of the Chagatai literary language

- ^ Doniger, Wendy (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 539. ISBN 0-87779-044-2.

- ^ Sicker, Martin (2000). The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege in Vienna. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 189. ISBN 0-275-96892-8.

Ismail was quite prepared to lend his support to the displaced Timurid prince, Zahir ad-Din Babur, who offered to accept Safavid suzerainty in return for help in regaining control of Transoxiana.

- ^ Erdogan, Eralp (July 2014). "Babür İmparatorluğu'nun Kuruluş Safhasında Şah İsmail ile Babür İttifakı" (PDF). Journal of History Studies (in Turkish). 6 (4): 31–39. doi:10.9737/historyS1150 (inactive 21 November 2024). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b c d e f Eraly 2007, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Farooqi, Naimur Rahman (2008). Mughal-Ottoman relations: a study of political & diplomatic relations between Mughal India and the Ottoman Empire, 1556–1748. pp. 13–14. OCLC 20894584.

- ^ a b c Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of medieval India : from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. New Delhi: Atlantic Publ. pp. 89–90. ISBN 81-269-0123-3.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2009). Medieval India:From Sultanat to the Mughals. Vol. 2. New Delhi: Har-Anand. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-241-1268-7.

- ^ Chandra (2009, pp. 27–28)

- ^ a b Chandra (2009, p. 28)

- ^ "Bābur, Mughal emperor". Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b Mahajan (2007, p. 438)

- ^ "Gwalior Fort: Rock Sculptures", A Cunningham, Archaeological Survey of India, pp. 364–70

- ^ Rao, K. V. Krishna (1991). Prepare Or Perish: A Study of National Security. Lancer Publishers. p. 453. ISBN 978-81-7212-001-6. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Wink 2012, pp. 157–58. "Reflecting on challenges he faced in India in his memoris Babur described Rana Sanga as one of the two greatest infidel king of India along with Deva Raya of South. who had grown so great by his audacity and sword and whose territory was so large that it covered significant portion of North-Western India"

- ^ a b c d e Lane-Poole, Stanley (1899). Babar. The Clarendon Press. pp. 182–83.

- ^ a b c Chandra, Satish (1999). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. Vol. 2 (1st ed.). New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications. p. 36. OCLC 36806798.

- ^ a b Hinnells, John; King, Richard (2006). Religion and Violence in South Asia: Theory and Practice. Routledge. pp. 101–114. ISBN 978-0-415-37291-6.

- ^ Elliot, H. M.; Dowson, John, eds. (1872). "Tuzak-i Babari" [The Autobiography of Babur]. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. Vol. IV. Translated by Leyden, John; Erskine, William. London: Trübner and Co. pp. 272, 275.

- ^ Prasad, Rajendra. India Divided (3rd ed.). Hind Kitabs Ltd. pp. 38–39.

- ^ Elliot, Henry Miers (1867–1877). "The Muhammadan Period". In John Dowson (ed.). The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. London: Trubner. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

... and on the same journey, he swam twice across the Ganges, as he said he had done with every other river he had met with.

- ^ Rahman, Tariq (2011). From Hindi to Urdu : a social and political history. Karachi: Oxford University Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0. OCLC 731974235.

- ^ "The Memoirs of Babur, Volume 1, chpt. 71". Memoirs of Zehīr-ed-Dīn Muhammed Bābur Emperor of Hindustan, Written by himself, in the Chaghatāi Tūrki. Translated by John Leyden and William Erskine, Annotated and Revised by Lucas King. Oxford University Press. 1921. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

Āisha Sultan Begum, the daughter of Sultan Ahmed Mirza, to whom I had been betrothed in the lifetime of my father and uncle, having arrived in Khujand, I now married her, in the month of Shābān. In the first period of my being a married man, though I had no small affection for her, yet, from modesty and bashfulness, I went to her only once in ten, fifteen, or twenty days. My affection afterwards declined, and my shyness increased; in so much, that my mother the Khanum, used to fall upon me and scold me with great fury, sending me off like a criminal to visit her once in a month or forty days.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Babur, Emperor of Hindustan; Beveridge, Annette Susannah (1922). The Babur-nama in English (Memoirs of Babur). London, Luzac. p. 120.

- ^ Babur, Emperor of Hindustan (2002, p. 89)

- ^ a b c d Babur (2006). "Babur's wives and children". In Hiro, Dilip (ed.). Babur Nama:Journal of Emperor Babur (2006 ed.). Penguin. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-14-400149-1.

- ^ Pope, Hugh (2005). Sons of the Conquerors, Overlook Duckworth, pp. 234–35.

- ^ F. Dale, Stephen (2004). THE GARDEN OF THE EIGHT PARADISES: Babur and the Culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483-1530). Brill. p. 171.

- ^ a b Eraly, Abraham (1997). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Moghuls. Penguin Books Limited. p. 29.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (1997). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Moghuls. Penguin Books Limited. p. 30.

- ^ Hasanov, S. (1981). Bobirning "Aruz risolasi" asari (in Uzbek). pp. 1-4. Uzbekistan: Fan.

- ^ Schimmel, A. (2004). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture. p. 26. India: Reaktion Books.

- ^ Eraly, A. (2000). Last Spring: The Lives and Times of Great Mughals. pp. 30-41. India: Penguin Books Limited.

- ^ "Biography of Abdur Rahim Khankhana". Archived from the original on 17 January 2006. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- ^ Dale, Stephen Frederic (2004). The garden of the eight paradises: Bābur and the culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483–1530). Brill. pp. 15, 150. ISBN 90-04-13707-6.

- ^ Balabanlilar, Lisa (2015). Imperial Identity in the Mughal Empire. Memory and Dynastic Politics in Early Modern South and Central Asia. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-857-72081-8.

- ^ Datta, Rangan (5 July 2024). "Agra beyond the Taj: Exploring tombs and gardens on the left bank of Yamuna". The Telegraph. My Kolkata. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ Goel, Shrishti (20 November 2020). "Did you know Mughal emperor Babur's body was kept at this place for 6 months before being buried in Kabul?". Dainik Jagaran. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ Dale, Stephen Frederic (2004). The garden of the eight paradises: Bābur and the culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483–1530). Brill. p. 216. ISBN 90-04-13707-6.

- ^ Morgan, David O.; Reid, Anthony, eds. (2010). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 3: The Eastern Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85031-5.

- ^ Prokhorov, A. M., ed. (1969–1978). "Babur". Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). Moscow: Soviet Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Muminov, Ibrohim, ed. (1972). "Bobur". Uzbek Soviet Encyclopedia (in Uzbek). Vol. 2. Tashkent. pp. 287–95.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bobur, Zahiriddin Muhammad (1989). "About This Edition". In A'zam Oʻktam (ed.). Boburnoma (in Uzbek). Tashkent: Yulduzcha. p. 3.

- ^ Fierman, William, ed. (1991). Soviet Central Asia. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8133-7907-4.

- ^ "Grandeur and Eternity: Zahiriddin Muhammad Bobur in Minds of People Forever". Embassy of Uzbekistan in Korea. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "The country's history on postage miniatures". Uzbekistan Today. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Sherali Joʻrayev: We Haven't Stopped. We Still Exist". BBC's Uzbek Service (in Uzbek). 13 April 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Wang, Zhihong. Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage. p. 121.

- ^ Rangoonwalla, Firoze; Das, Vishwanath (1970). Indian Filmography: Silent & Hindi Films, 1897–1969. J. Udeshi. p. 370. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Babur, Emperor of Hindustan (2002). The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. translated, edited and annotated by W. M. Thackston. Modern Library. ISBN 0-375-76137-3.

- ^ Lane-Poole (1899, pp. 12–13)

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 151. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

- ^ Ratnagar, Shereen (April 2004). "Archaeology at the Heart of a Political Confrontation: The Case of Ayodhya" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 45 (2): 239–59. doi:10.1086/381044. S2CID 149773944. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "ASI submits report on Ayodhya excavation". Rediff.com. Press Trust of India. 22 August 2003. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Suryamurthy, R (26 August 2003). "ASI findings may not resolve title dispute". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ Prasannan, R. (7 September 2003) "Ayodhya: Layers of truth" The Week (India), from Web Archive

- ^ "Proof of temple found at Ayodhya: ASI report". Rediff.com. Press Trust of India. 25 August 2003. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Shekhar, Kumar Shakti. "Ram temple existed before Babri mosque in Ayodhya: Archaeologist KK Muhammed". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Srivastava 2003.

- ^ Supriya Verma, Menon Shiv Sunni (2010), "Was There a Temple under the Babri Masjid? Reading the Archaeological 'Evidence'" Archived 26 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Economic & Political Weekly

- ^ Rajagopal, Krishnadas (10 November 2019). "Ayodhya verdict | Ruins don't always indicate demolition, observes Supreme Court". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "Highlights of the Ayodhya verdict". The Hindu. 9 November 2019. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

References

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 179

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 92

- Cambridge History of India, vol. III, Cambridge University Press, 1928

- Cambridge History of India, vol. IV, Cambridge University Press, 1937

- Eraly, Abraham (2007), Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Moghuls, Penguin Books Limited, ISBN 978-93-5118-093-7

- Srivastava, Sushil (25 October 2003). "The ASI Report – a review". Frontline. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

Books

- Alam, Muzaffar; Subrahmanyan, Sanjay, eds. (1998). The Mughal State, 1526–1750. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563905-6.

- Thackston, W. M. Jr. (2002). The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 9780375761379.

- Balabanlilar, Lisa (2012). Imperial Identity in the Mughal Empire: Memory and Dynastic Politics in Early Modern South and Central Asia. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Gascoigne, Bamber (1987) [1971]. The Great Moghuls. Photographs by Christina Gascoigne. London: Random House. ISBN 978-0224024747.

- Gommans, J. L. L. (2002). Mughal Warfare. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415239899.

- Gordon, Stewart (2008). When Asia was the World: Traveling Merchants, Scholars, Warriors, and Monks who created the "Riches of the East". Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81556-0.

- Hasan, Mohibbul (1985). Babur: Founder of the Mughal Empire in India. New Delhi: Manohar Publications.

- Irvine, William (1902). The Army of the Indian Moghuls: Its Organization and Administration. London: Brill.

- Jackson, Peter (1999). The Delhi Sultanate. A Political and Military History. Cambridge.

- Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge.

- Wink, Andre (2012). Akbar. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-78074-209-0.

- Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4.