Cancer (constellation)

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Cnc[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Cancri[1] |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkænsər/, genitive /ˈkæŋkraɪ/ |

| Symbolism | the Crab |

| Right ascension | 07h 55m 19.7973s–09h 22m 35.0364s[2] |

| Declination | 33.1415138°–6.4700689°[2] |

| Area | 506 sq. deg. (31st) |

| Main stars | 0 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 70 |

| Stars with planets | 10 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 2 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 0 |

| Brightest star | β Cnc (Tarf) (3.53m) |

| Messier objects | 2 |

| Meteor showers | Delta Cancrids |

| Bordering constellations | Lynx Gemini Canis Minor Hydra Leo Leo Minor (corner) |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −60°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of March. | |

Cancer is one of the thirteen ecliptical constellations and is located in the Northern celestial hemisphere. The symbol of the astrological sign with the same name (and which now covers roughly the constellation of Gemini) is ![]() (♋︎). Its name is Latin for crab and it is commonly represented as one. Cancer is a medium-size constellation with an area of 506 square degrees and its stars are rather faint, its brightest star Beta Cancri having an apparent magnitude of 3.5. It contains ten stars with known planets, including 55 Cancri, which has five: one super-earth and four gas giants, one of which is in the habitable zone and as such has expected temperatures similar to Earth. At the (angular) heart of this sector of our celestial sphere is Praesepe (Messier 44), one of the closest open clusters to Earth and a popular target for amateur astronomers.

(♋︎). Its name is Latin for crab and it is commonly represented as one. Cancer is a medium-size constellation with an area of 506 square degrees and its stars are rather faint, its brightest star Beta Cancri having an apparent magnitude of 3.5. It contains ten stars with known planets, including 55 Cancri, which has five: one super-earth and four gas giants, one of which is in the habitable zone and as such has expected temperatures similar to Earth. At the (angular) heart of this sector of our celestial sphere is Praesepe (Messier 44), one of the closest open clusters to Earth and a popular target for amateur astronomers.

Characteristics

[edit]Cancer is a medium-sized constellation that is bordered by Gemini to the west, Lynx to the north, Leo Minor to the northeast, Leo to the east, Hydra to the south, and Canis Minor to the southwest. The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is "Cnc".[3]

The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 3 main and 7 western edgework forming sides (illustrated in infobox). In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 07h 55m 19.7973s and 09h 22m 35.0364s, while the declination coordinates are between 33.1415138° and 6.4700689°.[2] Covering 506 square degrees or 0.921% of the sky, it ranks 31st of the 88 constellations in size. It can be seen at latitudes between +90° and -60° and is best visible at 9 p.m. during the month of March. Cancer borders the bright constellations of Leo, Gemini and Canis Minor. Under city skies, Cancer is invisible to the naked eye.

Features

[edit]Stars

[edit]Cancer is the dimmest of the zodiacal constellations, having only two stars above the fourth magnitude.[1] The German cartographer Johann Bayer used the Greek letters Alpha through Omega to label the most prominent stars in the constellation, followed by the letter A, then lowercase b, c and d.[4] Within the constellation's borders, there are 104 stars brighter than or equal to apparent magnitude 6.5.[a][6]

Also known as Altarf or Tarf,[7] Beta Cancri is the brightest star in Cancer at apparent magnitude 3.5.[8] Located 290 ± 30 light-years from Earth,[9] it is a binary star system, its main component an orange giant of spectral type K4III that is varies slightly from a baseline magnitude of 3.53—dipping by 0.005 magnitude over a period of 6 days.[10] An aging star, it has expanded to around 50 times the Sun's diameter and shines with 660 times its luminosity. It has a faint magnitude 14 red dwarf companion located 29 arcseconds away that takes 76,000 years to complete an orbit.[8] Altarf represents a part of Cancer's body.

At magnitude 3.9 is Delta Cancri, also known as Asellus Australis.[11] Located 131±1 light-years from Earth,[9] it is an orange-hued giant star that has swollen and cooled off the main sequence to become an orange giant with a radius 11 times and luminosity 53 times that of the Sun.[11] Its common name means "southern donkey".[1] The star also holds a record for the longest name, "Arkushanangarushashutu," derived from ancient Babylonian language, which translates to "the southeast star in the Crab."[citation needed] Delta Cancri also makes it easy to find X Cancri, the reddest star in the sky. Known as Asellus Borealis "northern donkey", Gamma Cancri is a white-hued A-type subgiant of spectral type A1IV and magnitude 4.67,[12] that is 35 times as luminous as of the Sun.[13] It is located 181 ± 2 light-years from Earth.[9]

Iota Cancri is a wide double star. The primary is a yellow-hued G-type bright giant star of magnitude 4.0,[14] located 330 ± 20 light-years from Earth.[9] It spent much of its stellar life as a B-type main sequence star before expanding and cooling to its current state as it spent its core hydrogen. The secondary is a white main sequence star of spectral type A3V and magnitude 6.57. Despite having different distances when measured by the HIPPARCOS satellite, the two stars share a common proper motion and appear to be a natural binary system.[14]

Located 181 ± 2 light-years from Earth,[9] Alpha Cancri (Acubens) is a multiple star with a primary component an apparent white main sequence star of spectral type A5 and magnitude 4.26. The secondary is of magnitude 12.0 and is visible in small amateur telescopes. Its common name means "the claw".[1] The primary is actually two very similar white main sequence stars that are 5.3 AU distant from each other and the secondary is two small main sequence stars, most likely red dwarfs, that are 600 AU from the main pair. Hence the system is a quadruple one.[15]

Zeta Cancri or Tegmine ("the shell") is a multiple star system that contains at least four stars located 82 light-years from Earth. The two brightest components are a binary star with an orbital period of 1100 years; the brighter component is a yellow-hued binary pair and the dimmer component is a yellow-hued star of magnitude 6.2. The brighter component is itself a binary star with a period of 59.6 years; its primary is of magnitude 5.6 and its secondary is of magnitude 6.0. This pair is at its greatest separation around 2019.[1]

Ten star systems have been found to have planets. Rho1 Cancri or 55 Cancri (or Copernicus[7]) is a binary star approximately 40.9 light-years distant from Earth. 55 Cancri consists of a yellow dwarf and a smaller red dwarf, with five planets orbiting the primary star; one low-mass planet that may be either a hot, water-rich world or a carbon planet and four gas giants. 55 Cancri A, classified as a rare "super metal-rich" star, is one of the top 100 target stars for NASA's Terrestrial Planet Finder mission, ranked 63rd on the list. The red dwarf 55 Cancri B, a suspected binary, appears to be gravitationally bound to the primary star, as the two share common proper motion.

YBP 1194 is a sunlike star in the open cluster M67 that has been found to have three planets.

Deep-sky objects

[edit]

Cancer is best known among stargazers as the home of Praesepe (Messier 44), an open cluster also called the Beehive Cluster, located right in the centre of the constellation. Located about 590 light-years from Earth, it is one of the nearest open clusters to our Solar System. M 44 contains about 50 stars, the brightest of which are of the sixth magnitude. Epsilon Cancri is the brightest member at magnitude 6.3. Praesepe is also one of the larger open clusters visible; it has an area of 1.5 square degrees, or three times the size of the full Moon.[1] It is most easily observed when Cancer is high in the sky. North of the Equator, this period stretches from February to May.

Ptolemy described the Beehive Cluster as "the nebulous mass in the breast of Cancer." It was one of the first objects Galileo observed with his telescope in 1609, spotting 40 stars in the cluster. Today, there are about 1010 high-probability members, most of them (68 percent) red dwarfs. The Greeks and Romans identified the nebulous object as a manger from which two donkeys, represented by the neighbouring stars [1213] Asellus Borealis and [1210] Asellus Australis, were eating. The stars represent the donkeys that the god Dionysus and his tutor Silenus rode in the war against the Titans. The ancient Chinese interpreted the object as a ghost or demon riding in a carriage, calling it a "cloud of pollen blown from under willow catkins."[citation needed]

The smaller, denser open cluster Messier 67 can also be found in Cancer, 2600 light-years from Earth. It has an area of approximately 0.5 square degrees, the size of the full Moon. It contains approximately 200 stars, the brightest of which are of the tenth magnitude.[1]

QSO J0842+1835 is a quasar used to measure the speed of gravity in VLBI experiment conducted by Edward Fomalont and Sergei Kopeikin in September 2002.

OJ 287 is a BL Lacertae object located 3.5 billion light years away that has produced quasi-periodic optical outbursts going back approximately 120 years, as first apparent on photographic plates from 1891. It was first detected at radio wavelengths during the course of the Ohio Sky Survey. Its central supermassive black hole is among the largest known, with a mass of 18 billion solar masses,[16] more than six times the value calculated for the previous largest object.[17]

History and mythology

[edit]Cancer was first recorded by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE in The Mathematical Syntaxis (a.k.a. Almagest), under the Greek name Καρκίνος (Karkinos).[18]

In the late 1890s, R.H. Allen asserted the following, with no supporting citation:

- "Cancer is said to have been the place for the Akkadian Sun of the South, perhaps from its position at the winter solstice in very remote antiquity; but afterwards it was associated with the fourth month Duzu[broken anchor] [araḫ Dumuzu], our June–July, and was known as the Northern Gate of Sun ..."[19]

Very few of Cancer's stars are visible to the naked eye, and its brightest stars are only 4th magnitude. Cancer was often considered the "Dark Sign", quaintly described as "black and without eyes".[citation needed] Dante, alluded to its faintness in Paradiso, and mentioned it being visible for the whole night when it culminated at midnight in a Northern Hemisphere winter month:

- Then a light among them brightened,

- so that, if Cancer one such crystal had,

- winter would have a month of only a day.[20][full citation needed]

Cancer was the backdrop to the Sun's most northerly position in the sky (the summer solstice) in ancient times, when the Earth's Sun-facing side was maximally tilted towards the south, in the Gregorian calendar kept within a few days of June 21. Equivalently, this is the date when the Sun is directly overhead as far north as 23.437° N. The northern-most parallel where the sun is directly overhead is still called the Tropic of Cancer, even though the corresponding position on the sky now occurs in Taurus, due to the precession of the equinoxes.[1]

The close conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 1563 – which was observed by Tycho Brahe and led him to note the inaccuracy of existing ephemerides and to begin his own program of astronomical measurements – occurred in Cancer not far from Praesepe.

In Greek mythology, Cancer is identified with the crab that appeared while Heracles fought the many-headed Lernaean Hydra. Hercules slew the crab after it bit him in the foot. Afterwards, the goddess Hera, an enemy of Heracles, placed the crab among the stars.[21]

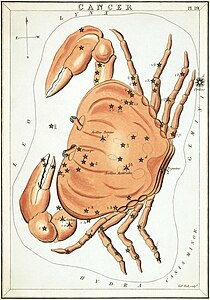

Illustrations

[edit]

The modern symbol for Cancer represents the pincers of a crab, but Cancer has been represented as many types of creatures, usually those living in the water, and always those with an exoskeleton.

In the Egyptian records of about 2000 BC it was described as Scarabaeus (Scarab), the sacred emblem of immortality. In Babylonia the constellation was known as MUL.AL.LUL, a name which can refer to both a crab and a snapping turtle. On boundary stones, the image of a turtle or tortoise appears quite regularly and it is believed that this represents Cancer since a conventional crab has not so far been discovered on any of these monuments.

There also appears to be a strong connection between the Babylonian constellation and ideas of death and a passage to the underworld, which may be the origin of these ideas in later Greek myths associated with Hercules and the Hydra.[22]

In the 12th century, an illustrated astronomical manuscript shows it as a water beetle. Albumasar writes of this sign in Flowers of Abu Ma'shar. A 1488 Latin translation depicts cancer as a large crayfish,[23] which also is the constellation's name in most Germanic languages. Jakob Bartsch and Stanislaus Lubienitzki, in the 17th century, described it as a lobster.

Names

[edit]R.H. Allen, in Star Names: Their lore and meanings, lists names for the constellation as follows:

- In Ancient Greece, Aratus called the crab Καρκινος (Karkinos), which was followed by Hipparchus and Ptolemy. The Alfonsine tables called it Carcinus, a Latinized form of the Greek word. Eratosthenes extended this as Καρκινος, Ονοι, και Φατνη (Karkinos, Onoi, kai Fatne): the Crab, [the] Asses, and [the] Crib. In Ancient Rome, Manilius and Ovid called the constellation Litoreus (shore-inhabiting). Astacus and Cammarus appear in various classic writers, while it is called Nepa in Cicero's De Finibus and the works of Columella, Plautus, and Varro; all of these words signify a crab, [a] lobster, or [a] scorpion.[24]

- Athanasius Kircher said that in Coptic Egypt it was Κλαρια (Klaria), the Bestia seu Statio Typhonis (the Power of Darkness). Jérôme Lalande identified this with Anubis, one of the Egyptian divinities commonly associated with Sirius.[24]

- The Indian language Sanskrit shares a common ancestor with Greek, and the Sanskrit name of Cancer is Karka and Karkata. In Telugu it is "Karkatakam", in Kannada "Karkataka" or "Kataka", in Tamil Kadagam, and in Sinhala Kagthaca. The later Hindus knew it as Kulira, from the Greek Κολουρος (Kolouros), the term originated by Proclus.[24]

Astrology

[edit]As of 2002[update], the Sun appears in the constellation Cancer from July 20 – August 9. In tropical astrology, the Sun is considered to be in the sign of Cancer from June 22 – July 22, and in sidereal astrology, from July 16 – August 16.

Equivalents

[edit]In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Cancer lie within the Vermilion Bird of the South (南方朱雀, Nán Fāng Zhū Què).[25]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ridpath & Tirion 2017, pp. 96–97

- ^ a b c "Cancer, constellation boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469–71. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ Wagman 2003, p. 60.

- ^ Bortle, John E. (February 2001). "The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale". Sky & Telescope. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Andromeda–Indus". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. "Al Tarf (Beta Cancri)". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the New Hipparcos Reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–64. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (3 May 2013). "NSV 3973". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. (14 May 2010). "Asellus Australis (Delta Cancri)". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "gam Cnc". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ McDonald, I.; Zijlstra, A. A.; Boyer, M. L. (2012). "Fundamental Parameters and Infrared Excesses of Hipparcos Stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 427 (1): 343–57. arXiv:1208.2037. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.427..343M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21873.x. S2CID 118665352.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. "Iota Cancri". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Acubens". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Valtonen, M. J.; Lehto, H. J.; Nilsson, K.; Heidt, J.; Takalo, L. O.; Sillanpää, A.; Villforth, C.; Kidger, M.; Poyner, G.; Pursimo, T.; Zola, S.; Wu, J. -H.; Zhou, X.; Sadakane, K.; Drozdz, M.; Koziel, D.; Marchev, D.; Ogloza, W.; Porowski, C.; Siwak, M.; Stachowski, G.; Winiarski, M.; Hentunen, V. -P.; Nissinen, M.; Liakos, A.; Dogru, S. (2008). "A massive binary black-hole system in OJ 287 and a test of general relativity" (PDF). Nature. 452 (7189): 851–853. arXiv:0809.1280. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..851V. doi:10.1038/nature06896. PMID 18421348. S2CID 4412396. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Shiga, David (10 January 2008). "Biggest black hole in the cosmos discovered". NewScientist.com news service.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (28 June 2018). Star Tales. ISD LLC. ISBN 9780718847814 – via Google Books.

- ^ Allen, R.H. (1898). Star Names: Their lore and meaning (Thesis). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. p. 108. Reprinted 1899 by Dover Books, New York, NY, and continually to the present.

- Quoted nearly verbatim by:

- Later authors continue to repeat the same quote from Allen (1898/1899) to the present.

- ^ Dante Alighieri. Paradiso. The Divine Comedy.

- ^ pseudo-Hyginus. De Astronomica. 2.23.

- ^ White 2008, pp. 79–82

- ^ "Flowers of Abu Ma'shar". World Digital Library. 1488. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Allen 1899, pp. 107–108

- ^ 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 5 月 27 日. Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899). "Cancer, the Crab". Star-names and Their Meanings. G.E. Stechert. pp. 107–114. Reprinted as Allen, Richard Hinckley (1963). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21079-0.

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2017). Stars and Planets Guide (5th ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-69-117788-5.

- Liungman, Carl G. (1994). Dictionary of Symbols. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31236-4.

- White, Gavin (2008), Babylonian Star-lore, Solaria Pubs

- Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

External links

[edit]- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Cancer

- Ian Ridpath's Star Tales – Cancer

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Cancer)