Cahokia people

kahokiaki | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| extinct as a tribe, descendants may have merged into the Peoria people[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| present-day United States (Illinois)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Miami-Illinois language | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion |

The Cahokia (Miami-Illinois: kahokiaki) were an Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe and member of the Illinois Confederation; their territory was in what is now the Midwestern United States in North America.[1]

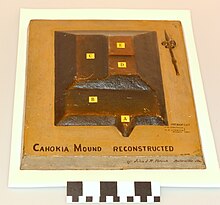

At the time of European contact with the Illini/Illinois Confederation, the peoples were located in what would later be organized as the states of Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas. In the 17th-century, the Cahokia lived near the massive precontact earthwork complex that Americans named the Cahokia Mounds.[1] By then, Cahokia Mounds had been abandoned for centuries. The Cahokia people were not related to the residents of Cahokia Mounds, who were most likely Dhegiha Siouan-speaking peoples.[2]

Meanings/Associations with "Cahokia"

[edit]The word Cahokia has several different meanings, referring to different peoples and often leading to misconceptions and confusion. Cahokia can refer to the physical mounds, a settlement that turned into a still existing small town in Illinois, the original mound builders of Cahokia who belonged to a larger group known as the Mississippians, or the Illinois Confederation subtribe of peoples who inhabited the area later, who will be the focus of this article.[3]

16th Century

[edit]Prior to 1500s

[edit]The Mississippian inhabitants who originally built the mounds experienced the heyday of the city during the 1100s. Widely known as one of America's first cities, it was all but abandoned by the 1400s due to common depopulation drivers such as drought and resource scarcity, characteristic of the climate changes of the time.[4]

1500s

[edit]Characteristic of many of the tribes of the Illinois Confederation, the Cahokia people were primarily migratory, hunting bison and moving with the changing seasons[5] Starting around the 1500s, the Cahokia people began to repopulate the Cahokia region. Unlike their previous Mississippian counterparts, the Illinois Confederation populated areas outside of what was considered to be the central city. They participated in small-scale agriculture and gardening, and even broke down into smaller groups for hunting and gathering during times of scarcity.[4]

17th century

[edit]The tribes of the Illinois Confederation faced much relocation during this century, as various attacks from other tribes took place. In 1673 when French explorers Jolliet and Marquette made contact with the region, the Illini occupied various corners of the midwest, with the Cahokia and Tamaroa occupying western Illinois and eastern Missouri. The total population of the Illinois Confederation was estimated to be around 10,000.[6] Factors such as warfare from groups such as the Iroquoi, and conflicts over resources such as firewood forced many tribes of the Illinois confederation to relocate.[6]

In 1699, the Cahokia and Tamaroa consolidated and completely relocated to Cahokia. French missionaries built missions in an attempt to convert the Cahokia people. They built the Tamaroa/Cahokia mission in 1699 CE.[7]

18th century

[edit]

In 1735, the Cahokia established a new village on Monks Mound.[6] The French then built the River L’Abbė mission.[7][8] The mission was built on the first terrace of Monks Mound within the city complex.[9] These multiple missions imply that Cahokia was a large enough tribe for the French Seminary of Foreign Missions to justify their construction and operation to continue their goals.

In 1752, Shawnee and Meskwaki allies of the British destroyed the primary Cahokia settlement.[1][10] Survivors joined the neighboring Michigamea.[10] The River L'Abbe mission operated until 1752 when most of the Cahokia were considered to have left the area. From 1776 to 1784, a trading post named the Cantine was located close to Monks Mound. French farmers settled in the area soon after.[9]

The Cahokia declined in number in the 18th century, due likely to mortality from warfare with other tribes, new infectious diseases, and cultural changes, such as Christianization, which further disrupted their society.[9]

The remnant Cahokia, along with the Michigamea, were absorbed by the Kaskaskia and finally the Peoria people.

19th century

[edit]Five Cahokia chiefs and headmen joined those of other Illinois tribes at the 1818 Treaty of Edwardsville (Illinois); they ceded to the United States a territory of theirs that was half of the size of the present state of Illinois.[11]

After the U.S. government implemented its Indian Removal policy in the early 19th century, the descendants were forcefully relocated to Kansas Territory and finally to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

Lifestyle

[edit]Like many of the tribes of the Illinois Confederation, society centered around the cultivation of Maize and hunting various game on the prairie. Researchers have found evidence of controlled burns, and this would be consistent with what is known about the Illinois Confederation, using fire to confuse herds of game such as buffalo, deer, and elk.[4][5] Hunting was done by the men, while women were tasked with preparing skins, building homes, harvesting crops, and gathering a variety of other wild plants.[5]

The Cahokia also made use of water travel, taking the Illinois River to visit the Peoria. In addition, they made use of the waterways to set up camps for seasonal hunts of game such as waterfowl. Despite mounting tensions with European missionaries, the Cahokia also began to adopt some European practices such as the use of Iron equipment and domesticating hogs.[12]

Legacy

[edit]Although the Cahokia tribe is no longer a distinct polity, its cultural traditions continue through the federally recognized Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma.[11][13]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Cahokia Indian Tribe History at Access Genealogy

- Malinowski, Sharon; Sheets, Anna (1998). Gale Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes, Volume 1. Gale. ISBN 0-7876-1086-0.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e May, Jon D. "Cahokia". The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ Emerson, Thomas E.; Pauketat, Timothy R. (2000). Cahokia: Domination and Ideology in the Mississippian World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780803287655.

- ^ "Cahokia: mirror of the cosmos". Choice Reviews Online. 40 (3): 40–1759-40-1759. November 1, 2002. doi:10.5860/choice.40-1759. ISSN 0009-4978.

- ^ a b c Anwar, Yasmin (January 2020). "New study debunks myth of Cahokia's Native American lost civilization". Berkeley News.

- ^ a b c O'Brien-Davis, Noreen. "Prairie Pages - The Illini" (PDF). Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. 1 (1): 4 – via Department of Natural Resources.

- ^ a b c "Corrections: Comparing the Modern Native American Presence in Illinois with Other States of the Old Northwest Territory". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 104 (1–2): 16. April 1, 2011. doi:10.2307/41201300. ISSN 1522-1067. JSTOR 41201300.

- ^ a b Morgan, M.J. (2010). Land of Big Rivers: French and Indian Illinois, 1699-1778. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-8564-5. OCLC 649913983.

- ^ Walthall, John A. The River L'Abbe Mission: A French colonial church for the Cahokia Illini on Monks Mound. OCLC 1107697896.

- ^ a b c White, A.J.; Munoz, Samuel E.; Schroeder, Sissel; Stevens, Lora R. (January 24, 2020). "After Cahokia: Indigenous Repopulation and Depopulation of the Horseshoe Lake Watershed AD 1400–1900". American Antiquity. 85 (2): 263–278. doi:10.1017/aaq.2019.103. ISSN 0002-7316.

- ^ a b Santella, Andrew (2007). Illinois Native Peoples. Heinemann Library. p. 13. ISBN 9781432902766.

- ^ a b Simpson, Linda. "The Tribes of the Illinois Confederacy." May 6, 2006. Accessed November 27, 2016.

- ^ MdFarland, Morgan (2005). "The watery world: The country of the Illinois, 1699–1778". University of Cincinnati ProQuest Dissertation & Theses. ProQuest 305004353 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "About | Peoria Tribe Of Indians of Oklahoma". Retrieved March 26, 2020.