List of CIA controversies

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) has been the subject of a number of controversies, both in and outside of the United States. Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA by Tim Weiner accuses the CIA of covert actions and human rights abuses.[1] Jeffrey T. Richelson of the National Security Archive has been critical of its claims.[2] Intelligence expert David Wise faulted Weiner for portraying Allen Dulles as "a doddering old man" rather than the "shrewd professional spy" he knew and for refusing "to concede that the agency's leaders may have acted from patriotic motives or that the CIA ever did anything right", but concluded: "Legacy of Ashes succeeds as both journalism and history, and it is must reading for anyone interested in the CIA or American intelligence since World War II."[3] The CIA itself has responded to the claims made in Weiner's book, and has described it as "a 600-page op-ed piece masquerading as serious history."[4]

Domestic wiretapping

[edit]In 1969, at the height of the antiwar movement in the US, CIA Director Helms received a message from Henry Kissinger ordering him to spy on the leaders of the groups requesting a moratorium on Vietnam. "Since 1962, three successive presidents had ordered the director of central intelligence to spy on Americans."[5]

Extraordinary rendition

[edit]

Extraordinary rendition is the apprehension and extrajudicial transfer of a person from one country to another.[6]

The term "torture by proxy" is used by some critics to describe situations in which the CIA[7][8][9][10] and other US agencies have transferred suspected terrorists to countries known to employ torture, whether they meant to enable torture or not. It has been claimed, though, that torture has been employed with the knowledge or acquiescence of US agencies (a transfer of anyone to anywhere for the purpose of torture is a violation of US law), although Condoleezza Rice (then the United States Secretary of State) stated that:

the United States has not transported anyone, and will not transport anyone, to a country when we believe he will be tortured. Where appropriate, the United States seeks assurances that transferred persons will not be tortured.[11]

Whilst the Obama administration has tried to distance itself from some of the harshest counterterrorism techniques, it has also said that at least some forms of renditions will continue.[12] The administration continued to allow rendition only "to a country with jurisdiction over that individual (for prosecution of that individual)" when there is a diplomatic assurance "that they will not be treated inhumanely."[13][14]

The US program has also prompted several official investigations in Europe into alleged secret detentions and unlawful inter-state transfers involving Council of Europe member states. A June 2006 report from the Council of Europe estimated 100 people had been kidnapped by the CIA on EU territory (with the cooperation of Council of Europe members), and rendered to other countries, often after having transited through secret detention centres ("black sites") used by the CIA, some located in Europe. According to the separate European Parliament report of February 2007, the CIA has conducted 1,245 flights, many of them to destinations where suspects could face torture, in violation of article 3 of the United Nations Convention Against Torture.[15]

Following the September 11 attacks the United States, in particular the CIA, has been accused of rendering hundreds of people suspected by the government of being terrorists—or of aiding and abetting terrorist organisations—to third-party states such as Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Uzbekistan. Such "ghost detainees" are kept outside judicial oversight, often without ever entering US territory, and may or may not ultimately be devolved to the custody of the United States.[16]

On October 4, 2001, a secret arrangement was made in Brussels, by all members of NATO. Lord George Robertson, British defence secretary and later NATO's secretary-general, would later explain that NATO members agree to provide "blanket overflight clearances for the United States and other allies' aircraft for military flights related to operations against terrorism."[17]

Security failures

[edit]

On December 30, 2009, a suicide attack occurred in the Forward Operating Base Chapman attack in the province of Khost, Afghanistan. Seven CIA officers, including the chief of the base, were killed and six others seriously wounded in the attack.[18]

The September 11th attacks have been viewed by some as an example of shortcomings for the United States' various intelligence agencies. George W Bush's administration has openly stated they did not foresee the possibility of airliners being used as weapons, despite regular briefings from intelligence agencies and prior incidents of airliners being hijacked domestically and abroad.[19][20]

Counterintelligence failures

[edit]Perhaps the most disruptive incident involving counterintelligence was CIA Counterintelligence Chief James Angleton's search for a mole or moles,[21] based on GRU Colonel Pyotr Popov's allegedly having told his Russia-born CIA handler, George Kisevalter in April of 1958 that he had recently heard a drunken GRU colonel brag that the Kremlin knew all about the Lockheed U-2 spy plane,[22] and the December 1961-on statements of a Soviet defector, KGB Major Anatoliy Golitsyn. A second defector, putative KGB officer Yuri Nosenko, who contacted the CIA in Geneva six months after Golitsyn's defection, challenged Golitsyn's claims, with the two calling one another Soviet double agents.[23] Many CIA officers fell under career-ending suspicion; the details of the relative truths and untruths from Nosenko and Golitsyn may never be released, or, in fact, may not be fully understood. The accusations also crossed the Atlantic to the British intelligence services, which also were damaged by molehunts.[24]

Edward Lee Howard, David Henry Barnett, both field operations officers, sold secrets to Russia. William Kampiles, a low-level worker in the CIA 24-hour Operations Center, sold the Soviets a detailed operational manual for the KH-11 reconnaissance satellite.[25]

Human rights concerns

[edit]

The CIA has been called into question for, at times, using torture, funding and training of groups and organizations that would later participate in killing of civilians and other non-combatants and would try or succeed in overthrowing democratically elected governments, human experimentation, and targeted killings and assassinations. The CIA has also been accused of a lack of financial and whistleblower controls which has led to waste and fraud.[26]

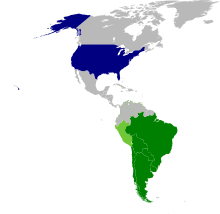

During Bush's year in charge of the CIA, the U.S. national security apparatus actively supported Operation Condor operations and right-wing military dictatorships in Latin America.[27][28] According to John Dinges, author of The Condor Years (The New Press 2003), documents released in 2015 revealed a CIA report dated April 28, 1978 that showed the agency by then had knowledge that U.S.-backed Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet ordered the assassination of Orlando Letelier, a leading political opponent living in exile in the United States.[29]

The Institute on Medicine as a Profession and the non-profit organization Open Society Foundations reviewed public records into the medical professions alleging complicity in the abuse of prisoners suspected of terrorism who were held in U.S. custody during the years after 9/11."[30][31] The reports found that health professionals "Aided cruel and degrading interrogations; Helped devise and implement practices designed to maximize disorientation and anxiety so as to make detainees more malleable for interrogation; and Participated in the application of excruciatingly painful methods of force-feeding of mentally competent detainees carrying out hunger strikes" are not all that surprising.[30] Medical professionals were sometimes used at black sites to monitor detainee health.[32] Whether or not the physicians were compelled is an open question.

Other human rights issues that are controversial include the case of Edward Snowden.[33][34][35] However, the significance of human right does not fall into this case regarding whether Snowden received his fair trial or not. Rather, the human rights associated with the Snowden leaks are regarding the types of document Snowden released. Snowden released a significant amount of information on the U.S. government's surveillance program of its citizens[36][37][38][39] to The Washington Post as well as foreign news reporters.

Particularly, "between on or about June 5, 2013, and June 9, 2013, classified information was published on the internet and in print by multiple newspapers, including The Washington Post and The Guardian. The articles and internet postings by The Washington Post and The Guardian included classified documents that were marked TOP SECRET. The Washington Post and The Guardian later revealed that SNOWDEN was the principal source for the classified information on or about June 9, 2013, in a videotaped interview with The Guardian, admitted that he was the person who illegally provided those documents to reporters. Evidence indicates that SNOWDEN had access to the classified documents in question; accessed those documents; and, subsequently, provided those documents to media outlets without authorization and in violation of U.S. law."[33]

Furthermore, the leaks included documents at many levels of the National Security Agency (NSA) electronic surveillance activities. "The Snowden leaks have generated broad public debate over issues of security, privacy, and legality inherent in the NSA's surveillance of communications by American citizens. The records include: White House and ODNI efforts to explain, justify, and defend the programs; Correspondence between outside critics and executive branch officials; Fact sheets and white papers distributed (and sometimes later withdrawn) by the government; Key laws and court decisions (both Supreme Court and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court); Documents on the Total Information Awareness (later Terrorist Information Awareness, or TIA) program, an earlier proposal for massive data collection Manuals on how to exploit the Internet for intelligence."[40]

External investigations and document releases

[edit]Several investigations led by the Church Committee, Rockefeller Commission and Pike Committee have been conducted about the CIA, and many documents have been declassified.[41]

Influencing public opinion and law enforcement

[edit]The CIA sometimes finds itself in conflict with other parts of the government when there is disagreement over the legality of specific covert programs. There is always the risk that one part of the government may make the covert operations of another part of the government public.[42]

CIA's recruitment of Nazis

[edit]

In 2014, The New York Times reported that "In the decades after World War II, the C.I.A. and other United States agencies employed at least a thousand Nazis as Cold War spies and informants and, as recently as the 1990s, concealed the government's ties to some still living in America, newly disclosed records and interviews show."[44]

According to Timothy Naftali, "The CIA's central concern [in recruiting former Nazi collaborators] was not so much the extent of the criminal's guilt as the likelihood that the agent's criminal past could remain a secret."[45]: 365

Iran-Contra

[edit]Drug trafficking

[edit]Two offices of the CIA Directorate of Analysis have analytical responsibilities in this area. The Office of Transnational Issues[46] applies unique functional expertise to assess existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security and provides the most senior U.S. policymakers, military planners, and law enforcement with analysis, warning, and crisis support.

CIA Crime and Narcotics Center[47] researches information on international narcotics trafficking and organized crime for policymakers and the law enforcement community. Since CIA has no domestic police authority, it sends its analytic information to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other law enforcement organizations, such as the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the United States Department of the Treasury (OFAC).

Another part of CIA, the Directorate of Operations, collects human intelligence (HUMINT) in these areas.

Research by Dr. Alfred W. McCoy, Gary Webb, and others has pointed to CIA involvement in narcotics trafficking across the globe, although the CIA officially denies such allegations.[48][40]

Lying to Congress

[edit]Nancy Pelosi has stated that the CIA repeatedly misled Congress since 2001 about waterboarding and other torture, though Pelosi admitted to being told about the programs.[49][50] Six members of Congress have claimed that Director of the CIA Leon Panetta admitted that over a period of several years since 2001 the CIA deceived Congress, including affirmatively lying to Congress.[51] Some Members of Congress believe that these lies to Congress are similar to CIA lies to Congress from earlier periods.[52]

In the early 1990s Richard Barlow asked his managers to correct the record when blatantly false statements had been made to Congress. The official mendacity only became public after Barlow sued the US Department of Defense for wrongful termination.[53]

Wikipedia editing

[edit]In 2007, the now defunct database Wikiscanner revealed that computers from the CIA had been used to edit articles on the English Wikipedia, including the Iraq War article in 2003, and the article on former CIA executive director William Colby. A spokeswoman for Wikipedia said in response that the changes may violate the encyclopedia's conflict-of-interest guidelines. CIA spokesman George Little said that he could not confirm if CIA computers were used to make the changes, claiming that "the agency always expects its computer systems to be used responsibly."[54]

Covert programs hidden from Congress

[edit]On July 10, 2009, House Intelligence subcommittee Chairwoman Representative Jan Schakowsky (D, IL) announced the termination of an unnamed CIA covert program described as "very serious" in nature which had been kept secret from Congress for eight years.[55]

It is not as if this was an oversight and over the years it just got buried. There was a decision under several directors of the CIA and administration not to tell the Congress.

CIA Director Panetta had ordered an internal investigation to determine why Congress had not been informed about the covert program. Chairman of the House Intelligence Committee Representative Silvestre Reyes announced that he is considering an investigation into alleged CIA violations of the National Security Act, which requires with limited exception that Congress be informed of covert activities. Investigations and Oversight Subcommittee Chairwoman Schakowsky indicated that she would forward a request for congressional investigation to HPSCI Chairman Silvestre Reyes.

Director Panetta did brief us two weeks ago—I believe it was on the 24th of June—... and, as had been reported, did tell us that he was told that the vice president had ordered that the program not be briefed to the Congress.

As mandated by Title 50 of the United States Code Chapter 15, Subchapter III, when it becomes necessary to limit access to covert operations findings that could affect vital interests of the U.S., as soon as possible the President must report at a minimum to the Gang of Eight (the leaders of each of the two parties from both the Senate and House of Representatives, and the chairs and ranking members of both the Senate Committee and House Committee for intelligence).[56] At the time the House was expected to support the 2010 Intelligence Authorization Bill including a provision that would require the President to inform more than 40 members of Congress about covert operations.[citation needed] The Obama administration threatened to veto the final version of a bill that included such a provision.[57] On July 16, 2008, the fiscal 2009 Intelligence Authorization Bill was approved by House majority containing stipulations that 75% of money sought for covert actions would be held until all members of the House Intelligence panel were briefed on sensitive covert actions. Under the George W. Bush administration, senior advisers to the President issued a statement indicating that if a bill containing this provision reached the President, they would recommend that he veto the bill.[58]

The program was rumored vis-à-vis leaks made by anonymous government officials on July 23, to be an assassinations program,[59][60] but this remains unconfirmed. "The whole committee was stunned. I think this is as serious as it gets," stated Anna Eshoo, Chairman, Subcommittee on Intelligence Community Management, U.S. House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI).

Allegations by Director Panetta indicate that details of a secret counterterrorism program were withheld from Congress under orders from former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney. This prompted Senators Dianne Feinstein and Patrick Leahy, Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee to insist that no one should go outside the law.[61] "The agency has not discussed publicly the nature of the effort, which remains classified," said agency spokesman Paul Gimigliano.[62]

The Wall Street Journal reported, citing former intelligence officials familiar with the matter, that the program was an attempt to carry out a 2001 presidential authorization to capture or kill al-Qaeda operatives.[63]

Intelligence Committee investigation

[edit]On July 17, 2009, the House Intelligence Committee said it was launching a formal investigation into the secret program.[64] Representative Silvestre Reyes announced the probe will look into "whether there was any past decision or direction to withhold information from the committee".

"Is giving your kid a test in school an inhibition on his free learning?" Holt said. "Sure, there are some people who are happy to let intelligence agencies go about their business unexamined. But I think most people when they think about it will say that you will get better intelligence if the intelligence agencies don't operate in an unexamined fashion."

Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky (D, IL), Chairman of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, who called for the investigation, stated that the investigation was intended to address CIA failures to inform Congress fully or accurately about four issues: C.I.A. involvement in the downing of a missionary plane mistaken for a narcotics flight in Peru in 2001, and two "matters that remain classified", as well as the rumored-assassinations question. In addition, the inquiry is likely to look at the Bush administration's program of eavesdropping without warrants and its detention and interrogation program.[66] U.S. Intelligence Chief Dennis Blair testified before the House Intelligence Committee on February 3, 2010, that the U.S. intelligence community is prepared to kill U.S. citizens if they threaten other Americans or the United States.[67] The American Civil Liberties Union has said this policy is "particularly troubling" because U.S. citizens "retain their constitutional right to due process even when abroad." The ACLU also "expressed serious concern about the lack of public information about the policy and the potential for abuse of unchecked executive power."[68]

Use of vaccination program in hunt for Osama bin Laden

[edit]The agency attracted widespread criticism after it used a local doctor in Pakistan to set up a hepatitis B vaccination program in Abbottabad in 2011 to obtain DNA samples from the occupants of a compound where it was suspected bin Laden was living, hoping to obtain samples from bin Laden or his children in order to confirm his presence. It is unknown whether any useful DNA was acquired from the program, but it was deemed not successful. The doctor was later arrested and sentenced to a lengthy prison term on allegedly unrelated charges.[69] Médecins Sans Frontières criticized the CIA for endangering and undermining trust in medical workers[70] and The New York Times reported that the CIA's action had increased resistance to vaccination programs in Pakistan.[71]

Improper search of computers used by Senate investigators

[edit]In July 2014 CIA Director John O. Brennan had to apologize to lawmakers because five CIA employees (two lawyers and three computer specialists) had surreptitiously searched Senate Intelligence Committee files and reviewed some committee staff members' e-mail on computers that were supposed to be exclusively for congressional investigators. Brennan ordered the creation of an internal personnel board, led by former senator Evan Bayh, to review the agency employees' conduct and determine "potential disciplinary measures."[72] However, according to some reports, Brennan didn't apologize for spying or doing anything wrong at all, even though his agency had been improperly accessing computers of the Senate Select Intelligence Committee (SSCI) and then, in the words of investigative reporter Dan Froomkin, "speaking a lie". This accusation was based on the CIA Director's earlier denials of Senator Dianne Feinstein's claims that the surreptitious CIA search of the SSCI computers occurred, was inappropriate, or "violated the separation of powers principles embodied in the United States Constitution, including the Speech and Debate clause" or other laws.[73][74][75]

Resignation of officials and agents who would not work for Donald Trump

[edit]In February 2017, reports emerged that key experts within the CIA were resigning because they would not work for U.S. President Donald Trump.[76] The Middle East Eye reported that two agents, Americans, who operated spy-rings within ISIS had resigned, because they "...did not want to see the contacts who worked for them sacrificed due to incompetence and anti-Muslim prejudice from within Trump's inner circle." Ned Price, a CIA official since 2006, stirred controversy when he published an op-ed in The Washington Post, explaining why he surprised himself by resigning, after he perceived Trump using his visit to CIA HQ for partisan political posturing.[77][78][79][80][81][82][83]

WikiLeaks' disclosure of CIA's cyber tools

[edit]In March 2017, WikiLeaks published more than 8,000 documents on the CIA. The confidential documents, codenamed Vault 7, dated from 2013 to 2016, included details on the CIA's software capabilities, such as the ability to compromise cars, smart TVs,[84] and web browsers, including Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Firefox, and Opera,[85][86] as well as the operating systems of most smartphones including Apple's iOS and Google's Android, and other operating systems such as Microsoft Windows, macOS, and Linux.[87] WikiLeaks did not name the source, but said that the files had "circulated among former U.S. government hackers and contractors in an unauthorized manner, one of whom has provided WikiLeaks with portions of the archive."[84]

In a 2017 speech addressing CSIS, CIA Director Mike Pompeo referred to WikiLeaks as "a non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors like Russia". He also said: "To give them the space to crush us with misappropriated secrets is a perversion of what our great Constitution stands for. It ends now."[88]

See also

[edit]- 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

- Abu Omar case

- Blue sky memo

- CIA activities in Indonesia

- CIA's relationship with the United States Military

- Classified information in the United States

- Cubana de Aviación Flight 455

- Family Jewels (Central Intelligence Agency)

- Freedom of Information Act (United States)

- George Bush Center for Intelligence

- Intellipedia

- Kryptos

- National Intelligence Board

- Operation Peter Pan

- Project MKUltra

- Reagan Doctrine

- Office of Strategic Services

- Title 32 of the Code of Federal Regulations

- U.S. Army and CIA interrogation manuals

- United States and state-sponsored terrorism

- United States Department of Homeland Security

- United States Intelligence Community

- The World Factbook, published by the CIA

- List of FBI controversies

Notes

[edit]- ^ Weiner, Tim (2007). Legacy of Ashes. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51445-3.

- ^ Richelson, Jeffrey (September 11, 2007). "Sins of Omission and Commission". Washington Decoded. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- ^ Wise, David (July 22, 2007). "Covert Action". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ Dujmovic, Nicholas (November 26, 2007). "Review of 'Legacy of Ashes: The History of CIA'". Studies in Intelligence. 51 (3). Center for the Study of Intelligence. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Weiner, Tim (2008). Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. New York: Random House. p. 342.

- ^ Garcia, Michael John (September 8, 2009). "Renditions: Constraints Imposed by Laws on Torture" (PDF). Congressional Research Service – via Federation of American Scientists. Link from "Online Resources". United States Counter-Terrorism Training and Resources for Law Enforcement. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (February 17, 2009). "Obama's War on Terror May Resemble Bush's in Some Areas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Background Paper on CIA's Combined Use of Interrogation Techniques" (PDF). American Civil Liberties Union. December 30, 2004. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Horton, Scott (August 28, 2009). "New CIA Docs Detail Brutal 'Extraordinary Rendition' Process". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Fact sheet: Extraordinary rendition". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^ "Remarks of Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice Upon Her Departure for Europe, 5 December 2005". U.S. State Department. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ "Obama preserves renditions as counter-terrorism tool". The Los Angeles Times. February 1, 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Erdbrink, Thomas (September 1, 2011). "N.Y. billing dispute reveals details of secret CIA rendition flights". The Washington Post.

- ^ Wang, Marian (September 6, 2011). "Under Obama Administration Renditions—and Secrecy Around Them—Continue". ProPublica. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ "Resolution 1507: Alleged secret detentions and unlawful inter-state transfers of detainees involving Council of Europe member states". Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. June 27, 2006. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010.

- ^ Mayer, Jane (February 14, 2005). "Outsourcing Torture: The secret history of America's 'extraordinary rendition' program". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ Grey, Stephen (November 25, 2007). "Flight logs reveal secret rendition". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ^ Rubin, Alissa J.; Mazzetti, Mark (December 31, 2009). "Afghan Base Hit by Attack Has Pivotal Role in Conflict". The New York Times. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ "9/11 Testimony of National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice". Center for American Progress. 2004-04-07. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ Macola, Ilaria Grasso (2021-06-25). "The world's most infamous aeroplane hijackings". Airport Technology. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ Wise, David (1992). Molehunt: The Secret Search for Traitors That Shattered the CIA. Random House. ISBN 0-394-58514-3.

- ^ Newman, John M. (2022). Uncovering Popov's Mole. U.S.A.: Self-published. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9798355050771.

- ^ Baer, Robert (2003). See No Evil: The True Story of a Ground Soldier in the CIA's War on Terrorism. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 1-4000-4684-X.

- ^ Wright, Peter; Greengrass, Paul (1987). Spycatcher. William Heinemann. ISBN 0-670-82055-5.

- ^ McKinley, Cynthia A. S. (1996). "When the Enemy Has Our Eyes". Federation of American Scientists.

- ^ Jones, Ishmael (January 7, 2010). "Intelligence Reform is the President's Urgent Challenge". The Washington Times.

- ^ "Where Gerald Ford Went Wrong". The Baltimore Chronicle. 2007.

- ^ "FIFA's Dirty Wars". The New Republic. December 15, 2017.

- ^ AM, John Dinges On 10/14/15 at 11:23 (October 14, 2015). "A Bombshell on Pinochet's Guilt, Delivered Too Late". Newsweek. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Neier, Aryeh; Rothman, David J. (November 4, 2013). "Doctors Aided CIA Torture, Records Show". Open Societies Foundation. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Paramaguru, Kharunya (November 4, 2013). "CIA Made Doctors Complicit in Torture After 9/11, Report Says". TIME. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Siems, Larry (2012). The Torture Report: What the Documents Say About America's Post 9-11 Torture Program. New York: OR Books. p. 216.

- ^ a b "The Snowden Affair: Electronic Briefing Book No. 436". The National Security Archive. September 4, 2013.

- ^ Harper, Lauren (July 12, 2013). "Not Quite Another "Year of the Spy"". Unredacted: The National Security Archive blog. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Harper, Lauren (January 17, 2014). "The "Top 10" Surveillance Lies Edward Snowden's Leaks Shed "Heat and Light" Upon". Unredacted: The National Security Archive blog. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "Office of the Inspector General's review of the President's Surveillance Program" (PDF). National Security Archive. March 24, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "Unclassified Report on the President's Surveillance Program" (PDF). National Security Archive. July 10, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "Minimization Procedures used by the National Security Agency in connection with Acquisitions of Foreign Intelligence" (PDF). National Security Archive. January 1, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "PRISM/US-984XN Overview or The SIGAD Used Most in NSA Reporting Overview" (PDF). National Security Archive. April 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Solomon, Norman. "Snow Job". Extra!. Archived from the original on February 11, 2005. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ Van Wagenen, James S. (April 4, 2007). "A Review of Congressional Oversight". Center for the Study of Intelligence. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ Saunders, Frances Stonor (1999). The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters. The New Press. ISBN 1-56584-664-8.

- ^ "U.S. Recruited Over 1,000 ex-Nazis as anti-Communist Spies, NY Times Reports". Haaretz. October 27, 2014.

- ^ "In Cold War, U.S. Spy Agencies Used 1,000 Nazis". The New York Times. October 26, 2014.

- ^ Naftali, Timothy (2005). "The CIA and Eichmann's Associates". U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis. Cambridge University Press. pp. 337–374. ISBN 978-0-521-61794-9.

- ^ "Office of Transnational Issues". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007.

- ^ "CIA Crime and Narcotics Center". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007.

- ^ Webb, Gary (1999). Dark Alliance. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-88836-393-7.

- ^ "Panetta Tells Lawmakers CIA Misled Congress Post-2001". Bloomberg. July 9, 2009.

- ^ Coomarasamy, James (May 14, 2009). "Pelosi says CIA lied on 'torture'". BBC News.

- ^ "House Dems: Panetta testified CIA has misled Congress repeatedly". CNN. July 9, 2009.

- ^ "CIA 'often lied to congressmen'". BBC News. July 9, 2009.

- ^ !<-- Layton (2007), Whistle-Blower's Fight For Pension Drags On, The Washington Post -->Lyndsey Layton (7 July 2007), Whistle-Blower's Fight For Pension Drags On, The Washington Post, Wikidata Q88306915

- ^ Mikkelsen, Randall (2007-08-16). "CIA, FBI computers used for Wikipedia edits". Reuters. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- ^ "Lawmaker: Panetta terminated secret program". NBC News. July 10, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ "US CODE: Title 50,413b. Presidential approval and reporting of covert actions". Legal Information Institute. July 20, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Hess, Pamela. "Lawmaker says CIA director ended secret program". The Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 14, 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2009 – via Google News.

- ^ Pincus, Walter (July 17, 2008). "House Passes Intelligence Authorization Bill". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "Senators: CIA concealment may have broken law". USA Today. Associated Press. July 12, 2009. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Hess, Pamela (July 13, 2009). "Calls grow for probe of CIA plan for al-Qaida hits". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "Cheney ordered intel withheld from Congress-senator". Reuters. July 12, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Gorman, Siobhan (July 15, 2009). "CIA Plan Envisioned Hit Teams Killing al Qaeda Leaders". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Gorman, Siobhan (July 13, 2009). "CIA Had Secret Al Qaeda Plan". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- ^ Zakaria, Tabassum (July 18, 2009). "House launches investigation into CIA program". Reuters. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "Holt Calls for Next Church Committee on CIA". The Washington Independent. July 29, 2009. Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Shane, Scott (July 18, 2009). "House Looks into Secrets Withheld From Congress". The New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ Starr, Barbara (February 4, 2010). "Intelligence chief: U.S. can kill Americans abroad". CNN.

- ^ "Intelligence Official Acknowledges Policy Allowing Targeted Killings of Americans". American Civil Liberties Union. February 4, 2010.

- ^ Shah, Saeed (July 11, 2011). "CIA organised fake vaccination drive to get Osama bin Laden's family DNA". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- ^ Shah, Saeed (14 July 2011). "CIA's fake vaccination programme criticised by Médecins Sans Frontières". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Masood, Salman (29 April 2019). "Pakistan's War on Polio Falters Amid Attacks on Health Workers and Mistrust". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Miller, Greg (July 31, 2014). "CIA director John Brennan apologizes for search of Senate committee's computers". The Washington Post.

- ^ Froomkin, Dan (September 26, 2014). "Anatomy of a Non-Denial Denial". The Intercept.

- ^ Feinstein, Dianne (March 11, 2014). "Statement on Intel Committee's CIA Detention, Interrogation Report". U.S. Senate.

- ^ Froomkin, Dan (August 1, 2014). "It's About the Lying". The Intercept.

- ^

Hearst, David (February 23, 2017). "CIA 'terrorist hunters' to quit in opposition to US president". Middle East Eye. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

Contracted agents, some of whom run networks of sources within al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) group have either quit or threatened to quit amid frustration in the intelligence services since Trump took office last month.

- ^ Price, Edward (February 20, 2017). "I didn't think I'd ever leave the CIA, but because of Trump I quit". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^

Millstein, Seth (February 20, 2017). "Who Is Edward Price? The CIA Agent Quit Because Of The Trump Administration". Bustle. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

Price joined the CIA in 2006 and most recently worked as a spokesman for the National Security Council, yet Trump's actions over his first month in office caused Price to conclude that he "cannot in good faith serve this administration as an intelligence professional."

- ^ Rosva, Edward (February 21, 2017). "National Security Council spokesman quits CIA, writes scathing editorial in Washington Post". Salon. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^

Sharman, Jon (February 21, 2017). "CIA analyst quits after 11 years because of Donald Trump's 'disturbing' behaviour". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

Edward Price joined up in 2006 and was "convinced that it was the ideal place to serve my country". He became a terrorism expert and worked under the George W Bush and Barack Obama administrations, recently serving on the staff of the National Security Council, and believed he would never leave.

- ^

Sommerfeldt, Chris (February 21, 2017). "Senior CIA analyst resigns because of President Trump's 'disturbing' actions in office". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

Over a decade ago, Edward Price told his father that he was going to get a job at the Central Intelligence Agency. It wouldn't just be his "first real job," he told his dad — it would be his career, passion and life.

- ^ Binelli, Raphael (February 21, 2017). "Un alto esponente della Cia si dimette: "Non posso servire l'amministrazione Trump"" [A senior official of the CIA resigns: "I can not serve the Trump administration"]. Il Giornale (in Italian). Milan. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^

Kelly, Mary Louise (February 20, 2017). "Disgusted By Trump, A CIA Officer Quits. How Many More Could Follow?". NPR. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

Now Price is 34. And it was another vivid image that led him to quit: that of President Trump on Jan. 21, his first full day in office, delivering a speech at CIA headquarters in Northern Virginia. Trump chose to speak in front of the CIA's wall of stars — stars that honor CIA officers who died in the line of duty.

- ^ a b Shane, Scott; Mazzetti, Mark; Rosenberg, Matthew (March 7, 2017). "WikiLeaks Releases Trove of Alleged C.I.A. Hacking Documents". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (March 7, 2017). "How the CIA Can Hack Your Phone, PC, and TV (Says WikiLeaks)". Wired. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ "WikiLeaks posts trove of CIA documents detailing mass hacking". CBS News. March 7, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Page, Carly (March 7, 2017). "Vault 7: Wikileaks reveals details of CIA's hacks of Android, iPhone Windows, Linux, MacOS, and even Samsung TVs". Computing.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (April 14, 2017). "Trump's CIA Director Pompeo, Targeting WikiLeaks, Explicitly Threatens Speech and Press Freedoms". The Intercept.

References

[edit]- Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2.

- Weiner, Tim (2007). Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51445-3. OCLC 82367780.

Further reading

[edit]- Agee, Philip (1975). Inside the Company: CIA Diary. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-140-04007-2.

- Aldrich, Richard J. (2001). The Hidden Hand: Britain, America and Cold War Secret Intelligence. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5423-3. OCLC 46513534.

- Andrew, Christopher (1996). For the President's Eyes Only. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-638071-9.

- Baer, Robert (2003). Sleeping with the Devil: How Washington Sold Our Soul for Saudi Crude. Crown. ISBN 1-4000-5021-9.

- Bearden, Milton; James Risen (2003). The Main Enemy: The Inside Story of the CIA's Final Showdown With the KGB. Random House. ISBN 0-679-46309-7.

- Coll, Steve (2004). Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-59420-007-6.

- Dujmovic, Nicholas, "Drastic Actions Short of War: The Origins and Application of CIA's Covert Paramilitary Function in the Early Cold War," Journal of Military History, 76 (July 2012), 775–808

- Gibson, Bryan R. (2015). Sold Out? US Foreign Policy, Iraq, the Kurds, and the Cold War. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-48711-7.

- Johnson, Loch K. (1991). America's Secret Power: The CIA in a Democratic Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505490-3.

- Jones, Ishmael (2010). The Human Factor: Inside the CIA's Dysfunctional Intelligence Culture. Encounter Books. ISBN 978-1-59403-223-3.

- Jones, Milo; Silberzahn, Philippe (2013). Constructing Cassandra, Reframing Intelligence Failure at the CIA, 1947–2001. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-9336-0.

- Leopold, Jason; Cormier, Anthony (December 1, 2021). "Secret CIA Files Say Staffers Committed Sex Crimes Involving Children". BuzzFeed.

- Marchetti, Victor; John D. Marks (1974). The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-48239-5.

- McCoy, Alfred W. (1972). The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia. Harper Colophon. ISBN 978-0-06-090328-2.

- McCoy, Alfred W. (2006). A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. New York: Owl Books (Henry Holt & Co.). ISBN 0-8050-8248-4. OCLC 78821099.

- Kessler, Ronald (2003). The CIA at War: Inside the Secret Campaign Against Terror. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-31932-0.

- Kinzer, Stephen (2003). All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-18549-0.

- Mahle, Melissa Boyle (2004). Denial and Deception: An Insider's View of the CIA from Iran-Contra to 9/11. Nation Books. ISBN 1-56025-649-4.

- Powers, Thomas (1979). The Man Who Kept the Secrets: Richard Helms & the CIA. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-50777-4.

- Prashad, Vijay (2020). Washington Bullets: A History of the CIA, Coups, and Assassinations. Monthly Review. ISBN 978-1-58367-906-7.

- Rositzke, Harry (1977). The CIA's Secret Operations. Reader's Digest Press. ISBN 0-88349-116-8.

- Ruth, Steven (2011). My Twenty Years as a CIA Officer: It's All About The Mission. Charleston, SC: CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4565-7170-2.

- Sheymov, Victor (1993). Tower of Secrets. U.S. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-764-8.

- Smith, W. Thomas Jr. (2003). Encyclopedia of the Central Intelligence Agency. Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-4667-0.

- Turner, Stansfield (2006). Burn Before Reading: Presidents, CIA Directors, and Secret Intelligence. Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-8666-8.

- Wallace, Robert; Melton, H. Keith; Schlesinger, Henry R. (2008). Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA's Spytechs, from Communism to al-Qaeda. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-94980-0. OCLC 18255288.

- Wise, David; Ross, Thomas B. (1964). The Invisible Government. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-43077-5.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Central Intelligence Agency at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- CIA Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room

- Landscapes of Secrecy: The CIA in History, Fiction and Memory (2011)

- Works by or about List of CIA controversies at the Internet Archive

- Works by List of CIA controversies at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Central Intelligence Collection at Internet Archive