CD44

The CD44 antigen is a cell-surface glycoprotein involved in cell–cell interactions, cell adhesion and migration. In humans, the CD44 antigen is encoded by the CD44 gene on chromosome 11.[5] CD44 has been referred to as HCAM (homing cell adhesion molecule), Pgp-1 (phagocytic glycoprotein-1), Hermes antigen, lymphocyte homing receptor, ECM-III, and HUTCH-1.

Tissue distribution and isoforms

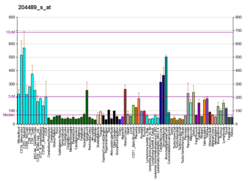

[edit]CD44 is expressed in a large number of mammalian cell types. The standard isoform, designated CD44s, comprising exons 1–5 and 16–20 is expressed in most cell types. CD44 splice variants containing variable exons are designated CD44v. Some epithelial cells also express a larger isoform (CD44E), which includes exons v8–10.[6]

Function

[edit]CD44 participates in a wide variety of cellular functions including lymphocyte activation, recirculation and homing, hematopoiesis, and tumor metastasis.

CD44 is a receptor for hyaluronic acid[7] and internalizes metals bound to hyaluronic acid[8][9] and can also interact with other ligands, such as osteopontin, collagens, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). CD44 function is controlled by its posttranslational modifications. One critical modification involves discrete sialofucosylations rendering the selectin-binding glycoform of CD44 called HCELL (for Hematopoietic Cell E-selectin/L-selectin Ligand).[10] (see below)

Transcripts for this gene undergo complex alternative splicing that results in many functionally distinct isoforms; however, the full length nature of some of these variants has not been determined. Alternative splicing is the basis for the structural and functional diversity of this protein, and may be related to tumor metastasis. Splice variants of CD44 on colon cancer cells display sialofucosylated HCELL glycoforms that serve as P-, L-, and E-selectin ligands and fibrin, but not fibrinogen, receptors under hemodynamic flow conditions pertinent to the process of cancer metastasis.[11][12]

CD44 gene transcription is at least in part activated by beta-catenin and Wnt signalling (also linked to tumour development).

HCELL

[edit]The HCELL glycoform was originally discovered on human hematopoietic stem cells and leukemic blasts,[10][13][14][15] and was subsequently identified on cancer cells.[12][16][17][18][19] HCELL functions as a "bone homing receptor", directing migration of human hematopoietic stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells to bone marrow.[14] Ex vivo glycan engineering of the surface of live cells has been used to enforce HCELL expression on any cell that expresses CD44.[20] CD44 glycosylation also directly controls its binding capacity to fibrin and immobilized fibrinogen.[11][21]

Clinical significance

[edit]The protein is a determinant for the Indian blood group system.

- CD44, along with CD25, is used to track early T cell development in the thymus.

- CD44 expression is an indicative marker for effector-memory T-cells. Memory cell proliferation (activation) can also be assayed in vitro with CFSE chemical tagging.

In addition, variations in CD44 are reported as cell surface markers for some breast and prostate cancer stem cells. In breast cancer research CD44+/CD24- expression is commonly used as a marker for breast CSCs and is used to sort breast cancer cells into a population enriched in cells with stem-like characteristics[22] and has been seen as an indicator of increased survival time in epithelial ovarian cancer patients.[23]

Endometrial cells in women with endometriosis demonstrate increased expression of splice variants of CD44, and increased adherence to peritoneal cells.[24]

CD44 variant isoforms are also relevant to the progression of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.[25][26]

Monoclonal antibodies against CD44 variants include bivatuzumab for v6.

CD44 in cancer

[edit]CD44 is a multistructural and multifunctional cell surface molecule involved in cell proliferation, cell differentiation, cell migration, angiogenesis, presentation of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors to the corresponding receptors, and docking of proteases at the cell membrane, as well as in signaling for cell survival. All these biological properties are essential to the physiological activities of normal cells, but they are also associated with the pathologic activities of cancer cells. Experiments in animals have shown that targeting of CD44 by antibodies, antisense oligonucleotides, and CD44-soluble proteins markedly reduces the malignant activities of various neoplasms, stressing the therapeutic potential of anti-CD44 agents.

High levels of the adhesion molecule CD44 on leukemic cells are essential to generate leukemia.[27] Furthermore, because alternative splicing and posttranslational modifications generate many different CD44 sequences, including, perhaps, tumor-specific sequences, the production of anti-CD44 tumor-specific agents may be a realistic therapeutic approach.[28]

In many cancers (renal cancer and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas are exceptions), a high level of CD44 expression is not always associated with an unfavorable outcome.[29] On the contrary, in some neoplasms CD44 upregulation is associated with a favorable outcome. This is true of prostate cancer, where the transcript variant CD44v5 (includes the fifth 'v5' exon) is associated with better prognosis (increased time to recurrence following surgery).[30][29] In prostate cancer, the exclusion of the v5 exon through alternative splicing was associated with the presence of RNA binding protein KHDRBS1 and became included in the presence of increased YTHDC1 or metadherin expression.[30]

In other cases different research groups analyzing the same neoplastic disease reached contradictory conclusions regarding the correlation between CD44 expression and disease prognosis, possibly due to differences in methodology. These problems must be resolved before applying anti-CD44 therapy to human cancers.[29]

Interactions

[edit]CD44 has been shown to interact with:

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000026508 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000005087 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Spring FA, Dalchau R, Daniels GL, Mallinson G, Judson PA, Parsons SF, et al. (May 1988). "The Ina and Inb blood group antigens are located on a glycoprotein of 80,000 MW (the CDw44 glycoprotein) whose expression is influenced by the In(Lu) gene". Immunology. 64 (1): 37–43. PMC 1385183. PMID 2454887.

- ^ Goodison S, Urquidi V, Tarin D (August 1999). "CD44 cell adhesion molecules". Molecular Pathology. 52 (4): 189–196. doi:10.1136/mp.52.4.189. PMC 395698. PMID 10694938.

- ^ Aruffo A, Stamenkovic I, Melnick M, Underhill CB, Seed B (June 1990). "CD44 is the principal cell surface receptor for hyaluronate". Cell. 61 (7): 1303–1313. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90694-a. PMID 1694723. S2CID 8217636.

- ^ Müller S, Sindikubwabo F, Cañeque T, Lafon A, Versini A, Lombard B, et al. (October 2020). "CD44 regulates epigenetic plasticity by mediating iron endocytosis". Nature Chemistry. 12 (10): 929–938. Bibcode:2020NatCh..12..929M. doi:10.1038/s41557-020-0513-5. PMC 7612580. PMID 32747755.

- ^ Solier S, Müller S, Cañeque T, Versini A, Mansart A, Sindikubwabo F, et al. (May 2023). "A druggable copper-signalling pathway that drives inflammation". Nature. 617 (7960): 386–394. Bibcode:2023Natur.617..386S. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06017-4. PMC 10131557. PMID 37100912.

- ^ a b Oxley SM, Sackstein R (November 1994). "Detection of an L-selectin ligand on a hematopoietic progenitor cell line". Blood. 84 (10): 3299–3306. doi:10.1182/blood.V84.10.3299.3299. PMID 7524735.

- ^ a b c Alves CS, Burdick MM, Thomas SN, Pawar P, Konstantopoulos K (April 2008). "The dual role of CD44 as a functional P-selectin ligand and fibrin receptor in colon carcinoma cell adhesion". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 294 (4): C907–C916. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00463.2007. PMID 18234849. S2CID 31373618.

- ^ a b Hanley WD, Burdick MM, Konstantopoulos K, Sackstein R (July 2005). "CD44 on LS174T colon carcinoma cells possesses E-selectin ligand activity". Cancer Research. 65 (13): 5812–5817. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4557. PMID 15994957.

- ^ Sackstein R, Dimitroff CJ (October 2000). "A hematopoietic cell L-selectin ligand that is distinct from PSGL-1 and displays N-glycan-dependent binding activity". Blood. 96 (8): 2765–2774. doi:10.1182/blood.V96.8.2765. PMID 11023510.

- ^ a b Sackstein R, Merzaban JS, Cain DW, Dagia NM, Spencer JA, Lin CP, et al. (February 2008). "Ex vivo glycan engineering of CD44 programs human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell trafficking to bone". Nature Medicine. 14 (2): 181–187. doi:10.1038/nm1703. PMID 18193058. S2CID 5095656.

- ^ Dimitroff CJ, Lee JY, Rafii S, Fuhlbrigge RC, Sackstein R (June 2001). "CD44 is a major E-selectin ligand on human hematopoietic progenitor cells". The Journal of Cell Biology. 153 (6): 1277–1286. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.6.1277. PMC 2192031. PMID 11402070.

- ^ Burdick MM, Chu JT, Godar S, Sackstein R (May 2006). "HCELL is the major E- and L-selectin ligand expressed on LS174T colon carcinoma cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (20): 13899–13905. doi:10.1074/jbc.M513617200. PMID 16565092.

- ^ a b Hanley WD, Napier SL, Burdick MM, Schnaar RL, Sackstein R, Konstantopoulos K (February 2006). "Variant isoforms of CD44 are P- and L-selectin ligands on colon carcinoma cells". FASEB Journal. 20 (2): 337–339. doi:10.1096/fj.05-4574fje. PMID 16352650. S2CID 23662591.

- ^ a b Napier SL, Healy ZR, Schnaar RL, Konstantopoulos K (February 2007). "Selectin ligand expression regulates the initial vascular interactions of colon carcinoma cells: the roles of CD44v and alternative sialofucosylated selectin ligands". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (6): 3433–3441. doi:10.1074/jbc.M607219200. PMID 17135256.

- ^ a b Thomas SN, Zhu F, Schnaar RL, Alves CS, Konstantopoulos K (June 2008). "Carcinoembryonic antigen and CD44 variant isoforms cooperate to mediate colon carcinoma cell adhesion to E- and L-selectin in shear flow". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (23): 15647–15655. doi:10.1074/jbc.M800543200. PMC 2414264. PMID 18375392.

- ^ Sackstein R (July 2009). "Glycosyltransferase-programmed stereosubstitution (GPS) to create HCELL: engineering a roadmap for cell migration". Immunological Reviews. 230 (1): 51–74. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00792.x. PMC 4306344. PMID 19594629.

- ^ a b Alves CS, Yakovlev S, Medved L, Konstantopoulos K (January 2009). "Biomolecular characterization of CD44-fibrin(ogen) binding: distinct molecular requirements mediate binding of standard and variant isoforms of CD44 to immobilized fibrin(ogen)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (2): 1177–1189. doi:10.1074/jbc.M805144200. PMC 2613610. PMID 19004834.

- ^ Li F, Tiede B, Massagué J, Kang Y (January 2007). "Beyond tumorigenesis: cancer stem cells in metastasis". Cell Research. 17 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1038/sj.cr.7310118. PMID 17179981.

- ^ Sillanpää S, Anttila MA, Voutilainen K, Tammi RH, Tammi MI, Saarikoski SV, et al. (November 2003). "CD44 expression indicates favorable prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 9 (14): 5318–5324. PMID 14614016.

- ^ Griffith JS, Liu YG, Tekmal RR, Binkley PA, Holden AE, Schenken RS (April 2010). "Menstrual endometrial cells from women with endometriosis demonstrate increased adherence to peritoneal cells and increased expression of CD44 splice variants". Fertility and Sterility. 93 (6): 1745–1749. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.012. PMC 2864724. PMID 19200980.

- ^ Wang SJ, Wong G, de Heer AM, Xia W, Bourguignon LY (August 2009). "CD44 variant isoforms in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma progression". The Laryngoscope. 119 (8): 1518–1530. doi:10.1002/lary.20506. PMC 2718060. PMID 19507218.

- ^ Assimakopoulos D, Kolettas E, Patrikakos G, Evangelou A (October 2002). "The role of CD44 in the development and prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas". Histology and Histopathology. 17 (4): 1269–1281. doi:10.14670/HH-17.1269. PMID 12371152.

- ^ Quéré R, Andradottir S, Brun AC, Zubarev RA, Karlsson G, Olsson K, et al. (March 2011). "High levels of the adhesion molecule CD44 on leukemic cells generate acute myeloid leukemia relapse after withdrawal of the initial transforming event". Leukemia. 25 (3): 515–526. doi:10.1038/leu.2010.281. PMC 3072510. PMID 21116281.

- ^ Eibl RH, Pietsch T, Moll J, Skroch-Angel P, Heider KH, von Ammon K, et al. (December 1995). "Expression of variant CD44 epitopes in human astrocytic brain tumors". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 26 (3): 165–170. doi:10.1007/bf01052619. PMID 8750182. S2CID 21251441.

- ^ a b c Naor D, Nedvetzki S, Golan I, Melnik L, Faitelson Y (November 2002). "CD44 in cancer". Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 39 (6): 527–579. doi:10.1080/10408360290795574. PMID 12484499. S2CID 30019668.

- ^ a b Luxton HJ, Simpson BS, Mills IG, Brindle NR, Ahmed Z, Stavrinides V, et al. (August 2019). "The Oncogene Metadherin Interacts with the Known Splicing Proteins YTHDC1, Sam68 and T-STAR and Plays a Novel Role in Alternative mRNA Splicing". Cancers. 11 (9): 1233. doi:10.3390/cancers11091233. PMC 6770463. PMID 31450747.

- ^ Bourguignon LY, Singleton PA, Zhu H, Diedrich F (August 2003). "Hyaluronan-mediated CD44 interaction with RhoGEF and Rho kinase promotes Grb2-associated binder-1 phosphorylation and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling leading to cytokine (macrophage-colony stimulating factor) production and breast tumor progression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (32): 29420–29434. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301885200. PMID 12748184.

- ^ Chen X, Khajeh JA, Ju JH, Gupta YK, Stanley CB, Do C, et al. (March 2015). "Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate clusters the cell adhesion molecule CD44 and assembles a specific CD44-Ezrin heterocomplex, as revealed by small angle neutron scattering". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 290 (10): 6639–6652. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.589523. PMC 4358296. PMID 25572402.

- ^ Midgley AC, Rogers M, Hallett MB, Clayton A, Bowen T, Phillips AO, et al. (May 2013). "Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)-stimulated fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation is mediated by hyaluronan (HA)-facilitated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and CD44 co-localization in lipid rafts". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (21): 14824–14838. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.451336. PMC 3663506. PMID 23589287.

- ^ Jalkanen S, Jalkanen M (February 1992). "Lymphocyte CD44 binds the COOH-terminal heparin-binding domain of fibronectin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 116 (3): 817–825. doi:10.1083/jcb.116.3.817. PMC 2289325. PMID 1730778.

- ^ a b Ilangumaran S, Briol A, Hoessli DC (May 1998). "CD44 selectively associates with active Src family protein tyrosine kinases Lck and Fyn in glycosphingolipid-rich plasma membrane domains of human peripheral blood lymphocytes". Blood. 91 (10): 3901–3908. doi:10.1182/blood.V91.10.3901. PMID 9573028.

- ^ Aruffo A, Stamenkovic I, Melnick M, Underhill CB, Seed B (June 1990). "CD44 is the principal cell surface receptor for hyaluronate". Cell. 61 (7): 1303–1313. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90694-A. PMID 1694723. S2CID 8217636.

- ^ Taher TE, Smit L, Griffioen AW, Schilder-Tol EJ, Borst J, Pals ST (February 1996). "Signaling through CD44 is mediated by tyrosine kinases. Association with p56lck in T lymphocytes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (5): 2863–2867. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.5.2863. PMID 8576267.

- ^ Zohar R, Suzuki N, Suzuki K, Arora P, Glogauer M, McCulloch CA, et al. (July 2000). "Intracellular osteopontin is an integral component of the CD44-ERM complex involved in cell migration". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 184 (1): 118–130. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200007)184:1<118::AID-JCP13>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 10825241. S2CID 11548419.

- ^ Bourguignon LY, Zhu H, Shao L, Chen YW (March 2001). "CD44 interaction with c-Src kinase promotes cortactin-mediated cytoskeleton function and hyaluronic acid-dependent ovarian tumor cell migration". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (10): 7327–7336. doi:10.1074/jbc.M006498200. PMID 11084024.

- ^ Shi X, Leng L, Wang T, Wang W, Du X, Li J, et al. (October 2006). "CD44 is the signaling component of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor-CD74 receptor complex". Immunity. 25 (4): 595–606. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.020. PMC 3707630. PMID 17045821.

Further reading

[edit]- Sackstein R (July 2011). "The biology of CD44 and HCELL in hematopoiesis: the 'step 2-bypass pathway' and other emerging perspectives". Current Opinion in Hematology. 18 (4): 239–248. doi:10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283476140. PMC 3145154. PMID 21546828.

- Sackstein R (July 2009). "Glycosyltransferase-programmed stereosubstitution (GPS) to create HCELL: engineering a roadmap for cell migration". Immunological Reviews. 230 (1): 51–74. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00792.x. PMC 4306344. PMID 19594629.

- Sackstein R (May 2004). "The bone marrow is akin to skin: HCELL and the biology of hematopoietic stem cell homing". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 122 (5): 1061–1069. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.09301.x. PMID 15140204.

- Konstantopoulos K, Thomas SN (2009). "Cancer cells in transit: the vascular interactions of tumor cells". Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 11: 177–202. doi:10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124949. PMID 19413512.

- Günthert U (1993). "CD44: A Multitude of Isoforms with Diverse Functions". Adhesion in Leukocyte Homing and Differentiation (PDF). Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 184. pp. 47–63. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78253-4_4. ISBN 978-3-642-78255-8. PMID 7508842.

- Yasuda M, Nakano K, Yasumoto K, Tanaka Y (2003). "CD44: functional relevance to inflammation and malignancy". Histology and Histopathology. 17 (3): 945–950. doi:10.14670/HH-17.945. PMID 12168806.

- Sun CX, Robb VA, Gutmann DH (November 2002). "Protein 4.1 tumor suppressors: getting a FERM grip on growth regulation". Journal of Cell Science. 115 (Pt 21): 3991–4000. doi:10.1242/jcs.00094. PMID 12356905. S2CID 14243743.

- Ponta H, Sherman L, Herrlich PA (January 2003). "CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 4 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1038/nrm1004. PMID 12511867. S2CID 19495756.

- Martin TA, Harrison G, Mansel RE, Jiang WG (May 2003). "The role of the CD44/ezrin complex in cancer metastasis". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 46 (2): 165–186. doi:10.1016/S1040-8428(02)00172-5. PMID 12711360.

External links

[edit]- Indian blood group system at BGMUT Blood Group Antigen Gene Mutation Database at NCBI, NIH

- Articles at IHOP.

- Human CD44 genome location and CD44 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.