Amantadine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Gocovri, Symadine, Symmetrel, others |

| Other names | 1-Adamantylamine; 1-Adamantanamine; 1-Aminoadamantane; Midantane; Midantan |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682064 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 86–90%[1] |

| Protein binding | 67%[1] |

| Metabolism | Minimal (mostly to acetyl metabolites)[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 10–31 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Urine[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.011.092 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H17N |

| Molar mass | 151.253 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 180 °C (356 °F) [6] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Amantadine, sold under the brand name Gocovri among others, is a medication used to treat dyskinesia associated with parkinsonism and influenza caused by type A influenzavirus, though its use for the latter is no longer recommended because of widespread drug resistance.[7][8] It is also used for a variety of other uses. The drug is taken by mouth.

Amantadine has a mild side-effect profile. Common neurological side effects include drowsiness, lightheadedness, dizziness, and confusion.[9] Because of its effects on the central nervous system (CNS), it should be combined cautiously with additional CNS stimulants or anticholinergic drugs. Given that it is cleared by the kidneys, amantadine is contraindicated in persons with end-stage kidney disease.[5] Due to its anticholinergic effects, it should be taken with caution by those with enlarged prostates or glaucoma.[10]

The pharmacology of amantadine is complex.[11][12] It acts as a sigma σ1 receptor agonist, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor negative allosteric modulator, dopaminergic agent, and weak NMDA receptor antagonist, among other actions.[11][12] The precise mechanism of action of its therapeutic effects in the treatment of CNS disorders is unclear.[11][12] The antiviral mechanism of action is inhibition of the influenza virus A M2 proton channel, which prevents endosomal escape (i.e., the release of viral genetic material into the host cytoplasm).[13][14] Amantadine is an adamantane derivative and is related to memantine and rimantadine.[15]

Amantadine was first used for the treatment of influenza A.[11] After its antiviral properties were initially reported in 1963, amantadine received approval for prophylaxis against the influenza virus A in 1966.[11][16] In 1968, its antiparkinsonian effects were serendipitously discovered.[11] In 1973, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved amantadine for use in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[11] In 2020, the extended-release formulation was approved for use in the treatment of levodopa-induced dyskinesia.[11][17]

Medical uses

[edit]Amantadine was initially developed to prevent replication of the influenza A virus.[18] Its main clinical use today is treatment of Parkinson's disease.[18] Other uses include treatment of drug-induced extrapyramidal side effects, motor fluctuations during levodopa therapy in Parkinson's disease, traumatic brain injury, and autistic spectrum disorders.[18]

Parkinson's disease

[edit]Amantadine is used to treat Parkinson's disease-related dyskinesia and drug-induced parkinsonism syndromes.[19] Amantadine may be used alone or in combination with another anti-Parkinson's or anticholinergic drug.[20] The specific symptoms targeted by amantadine therapy are dyskinesia and rigidity.[19] The extended release amantadine formulation is commonly used to treat dyskinesias in people receiving levodopa therapy for Parkinson's disease.[19] A 2003 Cochrane review had concluded evidence was insufficient to prove the safety or efficacy of amantadine to treat dyskinesia.[21]

In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported amantadine is not effective as a stand-alone parkinsonian therapy, but recommended it could be used in combination therapy with levodopa.[22]

Influenza A

[edit]Amantadine is not recommended for treatment or prophylaxis of influenza A in the United States.[7] Amantadine has no effect preventing or treating influenza B infections.[7] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found 100% of seasonal H3N2 and 2009 pandemic flu samples were resistant to adamantanes (amantadine and rimantadine) during the 2008–2009 flu season.[20][23]

The U.S. CDC guidelines recommend only neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza treatment and prophylaxis.[medical citation needed] The CDC recommends against amantadine and rimantadine to treat influenza A infections.[7]

Similarly, the 2011 WHO virology report showed all tested H1N1 influenza A viruses were resistant to amantadine.[8] WHO guidelines recommend against use of M2 inhibitors for influenza A.[medical citation needed] The continued high rate of resistance observed in laboratory testing of influenza A has reduced the priority of M2 resistance testing.[medical citation needed]

A 2014 Cochrane review did not find evidence for efficacy or safety of amantadine used for the prevention or treatment of influenza A.[24]

Extrapyramidal symptoms

[edit]An extended-release formulation of amantadine is used to treat levodopa-induced dyskinesia in patients with Parkinson's disease.[4] The WHO recommends the use of amantadine as a combination therapy to reduce levodopa side effects.[22]

Off-label uses

[edit]Fatigue in multiple sclerosis

[edit]A 2007 Cochrane literature review concluded that no overall evidence supports the use of amantadine in treating fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).[25] A follow-up 2012 Cochrane review stated that some amantadine-induced improvement in fatigue may occur in some people with MS.[26] Despite multiple control trials that have also demonstrated improvements in subjective and objective ratings of fatigue, no final conclusion has been drawn regarding its effectiveness.[27]

Consensus guidelines from the German Multiple Sclerosis Society (GMSS) in 2006 state that amantadine produces moderate improvement in subjective fatigue, problem solving, memory, and concentration. Thus, in 2006, GMSS guidelines recommended the use of amantadine in MS-related fatigue.[28]

In the UK, NICE recommends considering amantadine for MS fatigue.[29]

Disorders of consciousness

[edit]Disorders of consciousness (DoC) include coma, vegetative state (VS), and minimally conscious state (MCS). Amantadine has been shown to increase the rate of emergence from a MCS, defined by consistent demonstration of interactive communication and functional objective use. In traumatic brain injury patients in the intensive care unit, amantadine has also been shown in various randomized control trials to increase the rate of functional recovery and arousal, particularly in the time period immediately following an injury.[30] Also, significantly improved consciousness has been reported in patients treated for nontraumatic cases of DoC, such as in the case of a subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral hemorrhage, and hypoxic encephalopathy.[31] In 2018, the American Academy of Neurology updated treatment guidelines on the use of amantadine for patients with prolonged DoC, recommending the use of amantadine (100–200 mg b.i.d.) for adults with DoC 4 to 16 weeks after injury to support early functional recovery and reduce disability.[32]

Brain injury recovery

[edit]In various studies, amantadine and memantine have been shown to accelerate the rate of recovery from a brain injury.[33][34] The time-limited window following a brain injury is characterized by neuroplasticity, or the capacity of neurons in the brain to adapt and compensate after injury. Thus, physiatrists often start patients on amantadine as soon as impairments are recognized. Some case reports also show improved functional recovery with amantadine treatment occurring years after the initial brain injury.[30] Evidence is insufficient to determine if the functional gains are a result of effects through the dopamine or norepinephrine pathways. Some patients may benefit from direct dopamine stimulation with amantadine, while others may benefit more from other stimulants that act more on the norepinephrine pathway, such as methylphenidate.[30] If treatment with amantadine improves long-term outcomes or simply accelerates recovery is unclear.[33] Nonetheless, amantadine-induced acceleration of recovery reduces the burden of disability, lessens health-care costs, and minimizes psychosocial stressors in patients.[citation needed]

Contraindications

[edit]Amantadine is contraindicated in persons with end-stage kidney disease,[4] as the drug is renally cleared.[1][10][35]

Amantadine may have anticholinergic side effects. Thus, patients with an enlarged prostate or glaucoma should use with caution.[9]

Live attenuated vaccines are contraindicated while taking amantadine.[4] Amantadine might inhibit viral replication and reduce the efficacy of administered vaccines. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends avoiding amantadine for two weeks prior to vaccine administration and 48 hours afterward.[10]

Side effects

[edit]Amantadine is generally well tolerated and has a mild side effect profile.[36]

Neurological

[edit]Side effects include drowsiness (especially while driving), lightheadedness, falls, and dizziness.[4] Patients on amantadine should avoid combination with other CNS-depressing agents, such as alcohol. Excessive alcohol usage may increase the potential for CNS effects such as dizziness, confusion, and light-headedness.[9]

Rare severe adverse effects include neuroleptic malignant syndrome, depression, convulsions, psychosis, and suicidal ideation.[9] It has also been associated with disinhibited actions (gambling, sexual activity, spending, other addictions) and diminished control over compulsions.[4]

Amantadine may cause anxiety, feeling overexcited, hallucinations, and nightmares.[37]

Cardiovascular

[edit]Amantadine may cause orthostatic hypotension, syncope, and peripheral edema.[4]

Gastrointestinal

[edit]Amantadine has also been associated with dry mouth and constipation.[4]

Skin

[edit]Rare cases of skin rashes, such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome and livedo reticularis have also been reported in patients treated with amantadine.[38][39]

Kidney

[edit]Amantadine inhibits the kidney's active-transport removal and transfer of creatinine from blood to urine, which normally occurs in the proximal tubules of the nephrons. The active-transport removal mechanism accounts for about 15% of creatinine clearance, so amantadine may increase serum creatinine concentrations 15% above normal levels and give the false impression of mild kidney disease in patients whose kidneys are actually undamaged (because kidney function is often assessed by measuring the concentration of creatinine in blood.) Also, if the patient does have kidney disease, amantadine may cause it to appear as much as 15% worse than it actually is.[40]

Pregnancy and lactation

[edit]Amantadine is USFDA category C for pregnancy. Teratogenic effects have been observed in humans (case reports) and animal reproduction studies. Amantadine may also be present in breast milk and negatively alter breast milk production or excretion. The decision to breastfeed during amantadine therapy should consider the risk of infant exposure, the benefits of breastfeeding, and the benefits of the drug to the mother.[9]

Interactions

[edit]Amantadine may affect the CNS because of its dopaminergic and anticholinergic properties. The mechanisms of action are not fully known. Because of the CNS effects, caution is required when prescribing additional CNS stimulants or anticholinergic drugs.[10] Thus, concurrent use of alcohol with amantadine is not recommended because of enhanced CNS depressant effects.[41] In addition, antidopaminergic drugs such as metoclopramide and typical antipsychotics should be avoided.[42][43] These interactions are likely related to opposing dopaminergic mechanisms of action, which inhibits amantadine's anti-Parkinson effects.[medical citation needed]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]Central nervous system disorders

[edit]The mechanism of action of the antiparkinsonian effects of amantadine is poorly understood.[44] The effects of amantadine in Parkinson's disease were originally assumed to be anticholinergic or dopaminergic, but the situation soon proved more complicated than this.[11][12] The pharmacodynamics of amantadine are complex, and it interacts with many different biological targets at a variety of concentrations and hence potencies.[11][12]

The drug is a weak antagonist of the NMDA-type glutamate receptor, increases dopamine release, and blocks dopamine reuptake.[11][12][45][46][47] It is a negative allosteric modulator of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, specifically the α4β2 and α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.[11]

In 1993, amantadine was found to bind to the sigma σ1 receptor with relatively high affinity (Ki = 20.25 μM).[11][48] In 2004, it was discovered that amantadine and memantine bind to and act as agonists of the sigma σ1 receptor (Ki = 7.44 μM and 2.60 μM, respectively) and that activation of the σ1 receptor is potentially involved in the dopaminergic effects of amantadine at therapeutically relevant concentrations.[49] σ1 receptor activation is one of amantadine's more potent actions.[11][49] σ1 receptor agonists enhance tyrosine hydroxylase activity, modulate NMDA-stimulated dopamine release, increase dopamine release in the striatum in vivo, and decrease dopamine reuptake.[11] As such, σ1 receptor activation may be involved in the antiparkinsonian and other central nervous system effects of amantadine.[11][49]

Binding of amantadine to the NMDA receptor was first reported in 1989, and antagonism of the receptor was first reported in 1991.[11] Despite some reports, the NMDA receptor antagonism of amantadine is probably not its primary mechanism of action.[11][12] It occurs at relatively high concentrations and many of the effects of amantadine are different from those of NMDA receptor antagonists.[11] Some of its effects, such as enhancement of dopamine release in the striatum, are even reversed by NMDA receptor antagonists,[11] but NMDA receptor antagonism could still contribute to the effects of amantadine.[11]

Although some publications have reported that amantadine inhibits monoamine oxidase, the drug probably does not actually inhibit this enzyme.[11][12][50]

Amantadine shows amphetamine-like psychostimulant effects (e.g., stimulation of locomotor activity) in animals at sufficiently high doses.[12][51] It has been found to inhibit the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine and to induce the release of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.[12][11] The concentrations needed for these effects, though, are very high and may not be therapeutically relevant.[12][11] It is about 1/25th to 1/50th as potent as amphetamines.[12] Amantadine has been found to increase dopamine levels in the striatum.[12][11] It does not act as a monoaminergic activity enhancer.[51][52][53]

Amantadine is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, for example of PDE1.[11]

Amantadine has been found to increase aromatic amino acid decarboxylase expression.[11] This enzyme is responsible for the synthesis of dopamine from L-DOPA.[11] An imaging study in humans found that amantadine increased AADC activity in the striatum by up to 27%.[11]

Various additional actions of amantadine have been described.[11]

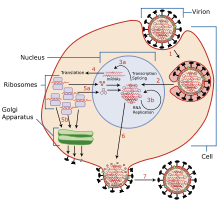

Influenza

[edit]

The mechanisms for amantadine's antiviral and antiparkinsonian effects are unrelated.[1][10] Amantadine targets the influenza A M2 ion channel protein. The M2 protein's function is to allow the intracellular virus to replicate (M2 also functions as a proton channel for hydrogen ions to cross into the vesicle), and exocytose newly formed viral proteins to the extracellular space (viral shedding). By blocking the M2 channel, the virus is unable to replicate because of impaired replication, protein synthesis, and exocytosis.[55]

Amantadine and rimantadine function in a mechanistically identical fashion, entering the barrel of the tetrameric M2 channel and blocking pore function—i.e., proton translocation.[20]

Resistance to the drug class is a consequence of mutations to the pore-lining amino acid residues of the channel, preventing both amantadine and rimantadine from binding and inhibiting the channel in their usual way.[56]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Amantadine is well-absorbed orally. The onset of action is usually within 48 hours when used for parkinsonian syndromes, including dyskinesia. As plasma concentrations of amantadine increase, the risk for toxicity increases.[57][58]

Half-life elimination averages eight days in patients with end-stage kidney disease. Amantadine is only minimally removed by hemodialysis.[58][59]

Amantadine is metabolized to a small extent (5–15%) by acetylation. It is mainly excreted (90%) unchanged in urine by kidney excretion.[57]

Chemistry

[edit]Amantadine is the organic compound 1-adamantylamine or 1-aminoadamantane, which consists of an adamantane backbone with an amino group substituted at one of the four tertiary carbons.[60] Rimantadine is a closely related adamantane derivative with similar biological properties;[61] both target the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus.[20]

Amantadine (1-aminoadamantane) is structurally related to other adamantanes including adapromine (1-(adamantan-1-yl)propan-1-amine), bromantane (N-(4-bromophenyl)adamantan-2-amine), memantine (1-amino-3,5-dimethyladamantane), and rimantadine (1-(1-aminoethyl)adamantane), among others.

History

[edit]Influenza A

[edit]Antiviral properties were first reported in 1963 at the University of Illinois Hospital in Chicago. In this amantadine trial study, volunteer college students were exposed to a viral challenge. The group who received amantadine (100 milligrams 18 hours before viral challenge) had less Asia influenza infections than the placebo group.[16] Amantadine received approval for the treatment of influenza virus A[62][63][64][65] in adults in 1976.[16] It was first used in West Germany in 1966. Amantadine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in October 1968, as a prophylactic agent against Asian (H2N2) influenza and received approval for prophylactic use for influenza A in 1976.[16][5][66]

During the 1980 influenza A epidemic, the first amantadine-resistance influenza viruses were reported. The frequency of amantadine resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses from 1991 and 1995 was as low as 0.8%. In 2004, the resistance frequency increased to 12.3%. A year later, resistance increase significantly to 96%, 72%, and 14.5% in China, South Korea, and the United States, respectively. By 2006, 90.6% of H3N2 strains and 15.6% of H1N1 were amantadine resistant. A majority of the amantadine-resistant H3N2 isolates (98.2%) was found to contain an S31N mutation in the M2 transmembrane domain that confers resistance to amantadine.[67] Currently, adamantane resistance is high among circulating influenza A viruses. Thus, they are no longer recommended for treatment of influenza A.[68]

Parkinson's disease

[edit]An incidental finding in 1969 prompted investigations about amantadine's effectiveness for treating symptoms of Parkinson's disease.[16] A woman with Parkinson's disease was prescribed amantadine to treat her influenza infection and reported her cogwheel rigidity and tremors improved. She also reported that her symptoms worsened after she finished the course of amantadine.[16] The published case report was not initially corroborated by any other instances by the medical literature or manufacturer data. A team of researchers looked at a group of 10 patients with Parkinson's disease and gave them amantadine. Seven of them showed improvement, which was convincing evidence for the need of a clinical trial, which included 163 patients with Parkinson's disease; 66% experienced subjective or objective reduction of symptoms with a maximum daily dose of 200 mg.[16][69] Additional studies followed patients for greater lengths of time and in different combinations of neurological drugs.[70] It was found to be a safe drug that could be used over long periods of time with few side effects as monotherapy or in combination with L-dopa or anticholinergic drugs.[16] By April 1973, the U.S. FDA approved amantadine for use in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[10][16]

In 2017, the U.S. FDA approved the use of amantadine in an extended-release formulation for the treatment of dyskinesia, an adverse effect of levodopa in people with Parkinson's disease.[71][72]

Society and culture

[edit]Names

[edit]Brand names of amantadine include Gocovri, Symadine, and Symmetrel.[73][1][74]

Recreational use

[edit]Recreational use of amantadine at supratherapeutic doses has been reported.[75] It is a weak NMDA receptor antagonist and is reported to produce dissociative and phencyclidine-like effects in animals and humans at sufficiently high doses.[75][76][77] However, the very long duration of action of amantadine (>40 hours) has likely limited its misuse potential.[75] Recreational use of the related drug memantine has similarly been reported.[75]

Veterinary misuse

[edit]In 2005, Chinese poultry farmers were reported to have used amantadine to protect birds against avian influenza.[78] In Western countries and according to international livestock regulations, amantadine is approved only for use in humans. Chickens in China have received an estimated 2.6 billion doses of amantadine.[78] Avian flu (H5N1) strains in China and southeast Asia are now resistant to amantadine, although strains circulating elsewhere still seem to be sensitive. If amantadine-resistant strains of the virus spread, the drugs of choice in an avian flu outbreak will probably be restricted to neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir and zanamivir, which block the action of viral neuraminidase enzyme on the surface of influenza virus particles.[67] Increasing incidence of oseltamivir resistance in circulating influenza strains (e.g., H1N1) exists, highlighting the need for new anti-influenza therapies.[79]

In September 2015, the U.S. FDA announced the recall of Dingo Chip Twists "Chicken in the Middle" dog treats because the product has the potential to be contaminated with amantadine.[80]

Research

[edit]Depression

[edit]Interest in and study of amantadine in the treatment of depression has arisen.[12][81][18][11][82] A 2017 systematic review of off-label augmentation for treatment of unipolar depression found two open-label studies of amantadine for augmenting imipramine and found that it was effective.[83] However, the quality of evidence was very low and no conclusions could be drawn about its effectiveness.[83] A 2022 systematic review of randomized controlled trials of glutamatergic agents for treatment-resistant depression identified one clinical trial of amantadine for this use.[82] Amantadine was found to be effective in treating depressive symptoms in the trial.[82] The mechanism of action of amantadine in the treatment of depression is unclear, but various mechanisms have been postulated.[18][81] These include dopaminergic actions like indirect enhancement of dopamine release, dopamine reuptake inhibition, and D2 receptor interactions, noradrenergic actions, glutamatergic actions such as NMDA receptor antagonism, and immunomodulation, among many others.[18][81][12]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

[edit]Amantadine has been studied in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[84] A 2010 randomized clinical trial showed similar improvements in ADHD symptoms in children treated with amantadine as in those treated with methylphenidate, with less frequent side effects.[85] A 2021 retrospective study showed that amantadine may serve as an effective adjunct to stimulants for ADHD-related symptoms and appears to be a safer alternative to second- or third-generation antipsychotics.[86]

COVID-19

[edit]Amantadine has been studied in the treatment of COVID-19.[87][88]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Symmetrel (amantadine hydrochloride)" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Limited. 29 June 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Trilasym 50 mg/ 5 ml Oral Solution – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 24 September 2019. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Gocovri- amantadine capsule, coated pellets". DailyMed. 26 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "Gocovri- amantadine capsule, coated pellets". DailyMed. 26 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). CRC Press. p. 3.524. ISBN 9781498754293.

- ^ a b c d "Influenza Antiviral Medications: Summary for Clinicians". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 17 April 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Summary of influenza antiviral susceptibility surveillance findings". World Health Organization (WHO). September 2010 – March 2011. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Chang C, Ramphul K (2020). "Amantadine". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29763128. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Symmetrel (Amantadine Hydrochloride, USP) fact sheet" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Danysz W, Dekundy A, Scheschonka A, Riederer P (February 2021). "Amantadine: reappraisal of the timeless diamond-target updates and novel therapeutic potentials". J Neural Transm (Vienna). 128 (2): 127–169. doi:10.1007/s00702-021-02306-2. PMC 7901515. PMID 33624170.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Huber TJ, Dietrich DE, Emrich HM (March 1999). "Possible use of amantadine in depression". Pharmacopsychiatry. 32 (2): 47–55. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979191. PMID 10333162.

- ^ James SH, Whitley RJ (2017). "Influenza Viruses". Infectious Diseases. Elsevier. pp. 1465–1471.e1. doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-6285-8.00172-6. ISBN 978-0-7020-6285-8.

- ^ Balgi AD, Wang J, Cheng DY, Ma C, Pfeifer TA, Shimizu Y, et al. (1 February 2013). Bouvier NM (ed.). "Inhibitors of the influenza A virus M2 proton channel discovered using a high-throughput yeast growth restoration assay". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e55271. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...855271B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055271. PMC 3562233. PMID 23383318.

- ^ Ragshaniya A, Kumar V, Tittal RK, Lal K (March 2024). "Nascent pharmacological advancement in adamantane derivatives". Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 357 (3): e2300595. doi:10.1002/ardp.202300595. PMID 38128028.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hubsher G, Haider M, Okun MS (April 2012). "Amantadine: the journey from fighting flu to treating Parkinson disease". Neurology. 78 (14): 1096–9. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8f0d. PMID 22474298. S2CID 21515610.

- ^ Hauser RA, Lytle J, Formella AE, Tanner CM (March 2022). "Amantadine delayed release/extended release capsules significantly reduce OFF time in Parkinson's disease". npj Parkinson's Disease. 8 (1): 29. doi:10.1038/s41531-022-00291-1. PMC 8933492. PMID 35304480.

- ^ a b c d e f Raupp-Barcaro IF, Vital MA, Galduróz JC, Andreatini R (2018). "Potential antidepressant effect of amantadine: a review of preclinical studies and clinical trials". Braz J Psychiatry. 40 (4): 449–458. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2393. PMC 6899375. PMID 29898194.

- ^ a b c Rascol O, Fabbri M, Poewe W (December 2021). "Amantadine in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and other movement disorders". The Lancet. Neurology. 20 (12): 1048–1056. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(21)00249-0. PMID 34678171. S2CID 239031883.

- ^ a b c d Golan DE, Armstrong EJ, Armstrong AW (2017). Principles of pharmacology: the pathophysiologic basis of drug therapy (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 142, 199, 205t, 224t, 608, 698–700. ISBN 9781451191004. OCLC 914593652.

- ^ Crosby NJ, Deane KH, Clarke CE, et al. (Cochrane Movement Disorders Group) (22 April 2003). "Amantadine for dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (2): CD003467. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003467. PMC 8715285. PMID 12804468.

- ^ a b Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR, eds. (2009). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization (WHO). p. 242. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 978-9241547659.

- ^ "Seasonal Influenza (Flu) – Weekly Report: Influenza Summary Update". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 5 September 2009.

- ^ Alves Galvão MG, Rocha Crispino Santos MA, Alves da Cunha AJ, et al. (Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group) (November 2014). "Amantadine and rimantadine for influenza A in children and the elderly". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (11): CD002745. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002745.pub4. PMC 7093890. PMID 25415374.

- ^ Pucci E, Branãs P, D'Amico R, Giuliani G, Solari A, Taus C, et al. (Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis and Rare Diseases of the CNS Group) (January 2007). "Amantadine for fatigue in multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (1): CD002818. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002818.pub2. PMC 6991937. PMID 17253480.

- ^ Payne C, Wiffen PJ, Martin S (April 2017). "WITHDRAWN: Interventions for fatigue and weight loss in adults with advanced progressive illness". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: CD008427. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008427. PMC 6478103. PMID 28387447.

- ^ Generali JA, Cada DJ (September 2014). "Amantadine: multiple sclerosis-related fatigue". Hospital Pharmacy. 49 (8): 710–2. doi:10.1310/hpj4908-710. PMC 4252198. PMID 25477595.

- ^ Henze T, Rieckmann P, Toyka KV (2006). "Symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Therapy Consensus Group (MSTCG) of the German Multiple Sclerosis Society". European Neurology. 56 (2): 78–105. doi:10.1159/000095699. PMID 16966832. S2CID 5069086.

- ^ "Recommendations | Multiple sclerosis in adults: Management | Guidance | NICE". 22 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Ma HM, Zafonte RD (February 2020). "Amantadine and memantine: a comprehensive review for acquired brain injury". Brain Injury. 34 (3): 299–315. doi:10.1080/02699052.2020.1723697. PMID 32078407. S2CID 211232548.

- ^ Gao Y, Ma L, Liang F, Zhang Y, Yang L, Liu X, et al. (July 2020). "The use of amantadine in patients with unresponsive wakefulness syndrome after severe cerebral hemorrhage". Brain Injury. 34 (8): 1084–1088. doi:10.1080/02699052.2020.1780315. PMID 32552090. S2CID 219909194.

- ^ Giacino JT, Katz DI, Schiff ND, Whyte J, Ashman EJ, Ashwal S, et al. (September 2018). "Practice guideline update recommendations summary: Disorders of consciousness: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research". Neurology. 91 (10): 450–460. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005926. PMC 6139814. PMID 30089618.

- ^ a b Giacino JT, Whyte J, Bagiella E, Kalmar K, Childs N, Khademi A, et al. (March 2012). "Placebo-controlled trial of amantadine for severe traumatic brain injury". The New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (9): 819–26. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102609. PMID 22375973.

- ^ Kafi H, Salamzadeh J, Beladimoghadam N, Sistanizad M, Kouchek M (2014). "Study of the neuroprotective effects of memantine in patients with mild to moderate ischemic stroke". Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 13 (2): 591–8. PMC 4157035. PMID 25237355.

- ^ "Symmetrel (Amantadine) Prescribing Information" (PDF). Endo Pharmaceuticals. May 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ Hosenbocus S, Chahal R (February 2013). "Amantadine: a review of use in child and adolescent psychiatry". Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 22 (1): 55–60. PMC 3565716. PMID 23390434.

- ^ Amantadine Hydrochloride package leaflet, Manx Healthcare, 1/24; Common possible side effects (may affect up to one in 10 people)

- ^ Bahrani E, Nunneley CE, Hsu S, Kass JS (March 2016). "Cutaneous Adverse Effects of Neurologic Medications". CNS Drugs. 30 (3): 245–67. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0318-7. PMID 26914914. S2CID 10560952.

- ^ Vollum DI, Parkes JD, Doyle D (June 1971). "Livedo reticularis during amantadine treatment". British Medical Journal. 2 (5762): 627–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5762.627. PMC 1796527. PMID 5580722.

- ^ "Some medicines increase serum creatinine without affecting glomerular function".

- ^ Gocovri (amantadine) extended-release capsules [prescribing information]. Emeryville, CA: Adamas Pharma, LLC; August 2017

- ^ Reglan (metoclopramide) [prescribing information]. Baudette, MN: ANI Pharmaceuticals Inc; August 2017

- ^ Tarsy D, Parkes JD, Marsden CD (April 1975). "Metoclopramide and pimozide in Parkinson's disease and levodopa-induced dyskinesias". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 38 (4): 331–335. doi:10.1136/jnnp.38.4.331. PMC 491929. PMID 1095689.

- ^ "Amantadine – MeSH". NCBI.

- ^ Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. p. 3962. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ^ Kornhuber J, Bormann J, Hübers M, Rusche K, Riederer P (April 1991). "Effects of the 1-amino-adamantanes at the MK-801-binding site of the NMDA-receptor-gated ion channel: a human postmortem brain study". European Journal of Pharmacology. 206 (4): 297–300. doi:10.1016/0922-4106(91)90113-v. PMID 1717296.

- ^ Blanpied TA, Clarke RJ, Johnson JW (March 2005). "Amantadine inhibits NMDA receptors by accelerating channel closure during channel block". The Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (13): 3312–22. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4262-04.2005. PMC 6724906. PMID 15800186.

- ^ Kornhuber J, Schoppmeyer K, Riederer P (December 1993). "Affinity of 1-aminoadamantanes for the sigma binding site in post-mortem human frontal cortex". Neurosci Lett. 163 (2): 129–131. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(93)90362-o. PMID 8309617.

- ^ a b c Peeters M, Romieu P, Maurice T, Su TP, Maloteaux JM, Hermans E (April 2004). "Involvement of the sigma 1 receptor in the modulation of dopaminergic transmission by amantadine". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (8): 2212–20. doi:10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03297.x. PMID 15090047. S2CID 19479968.

- ^ Strömberg U, Svensson TH (November 1971). "Further studies on the mode of action of amantadine". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 30 (3): 161–71. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1971.tb00646.x. PMID 5171936.

- ^ a b Shimazu S, Takahata K, Katsuki H, Tsunekawa H, Tanigawa A, Yoneda F, et al. (June 2001). "(-)-1-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-2-propylaminopentane enhances locomotor activity in rats due to its ability to induce dopamine release". Eur J Pharmacol. 421 (3): 181–189. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01040-8. PMID 11516435.

- ^ Yoneda F, Moto T, Sakae M, Ohde H, Knoll B, Miklya I, et al. (May 2001). "Structure-activity studies leading to (-)1-(benzofuran-2-yl)-2-propylaminopentane, ((-)BPAP), a highly potent, selective enhancer of the impulse propagation mediated release of catecholamines and serotonin in the brain". Bioorg Med Chem. 9 (5): 1197–1212. doi:10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00002-5. PMID 11377178.

- ^ Knoll J, Yoneda F, Knoll B, Ohde H, Miklya I (December 1999). "(-)1-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-2-propylaminopentane, [(-)BPAP], a selective enhancer of the impulse propagation mediated release of catecholamines and serotonin in the brain". Br J Pharmacol. 128 (8): 1723–1732. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0702995. PMC 1571822. PMID 10588928.

- ^ Thomaston JL, Alfonso-Prieto M, Woldeyes RA, Fraser JS, Klein ML, Fiorin G, et al. (November 2015). "High-resolution structures of the M2 channel from influenza A virus reveal dynamic pathways for proton stabilization and transduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (46): 14260–5. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11214260T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1518493112. PMC 4655559. PMID 26578770.

- ^ "Amantadine". PubChem. U.S. Library of Medicine. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Hussain M, Galvin HD, Haw TY, Nutsford AN, Husain M (20 April 2017). "Drug resistance in influenza A virus: the epidemiology and management". Infection and Drug Resistance. 10: 121–134. doi:10.2147/idr.s105473. PMC 5404498. PMID 28458567.

- ^ a b "Amantadine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Amantadine – FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Deleu D, Northway MG, Hanssens Y (2002). "Clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of drugs used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 41 (4): 261–309. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241040-00003. PMID 11978145. S2CID 39359348.

- ^ "Amantadine". drugbank.ca. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ "Rimantadine hydrochloride (CHEBI:8865)". ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Hounshell DA, Smith JK (1988). Science and Corporate Strategy: Du Pont R&D, 1902–1980 John. Cambridge University Press. p. 469. ISBN 978-0521327671.

- ^ "Sales of flu drug by du Pont unit a 'disappointment'". The New York Times. Wilmington, Delaware. 5 October 1982. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ Maugh TH (November 1979). "Panel urges wide use of antiviral drug". Science. 206 (4422): 1058–60. Bibcode:1979Sci...206.1058M. doi:10.1126/science.386515. PMID 386515.

- ^ Maugh TH (April 1976). "Amantadine: an alternative for prevention of influenza". Science. 192 (4235): 130–1. doi:10.1126/science.192.4235.130. PMID 17792438.

- ^ "International Review of Neurobiology", Recent advances in the use of Drosophila in neurobiology and neurodegeneration, International Review of Neurobiology, vol. 99, Elsevier, 2011, pp. i–iii, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-387003-2.00010-0, ISBN 978-0-12-387003-2, retrieved 11 November 2020

- ^ a b Kumar B, Asha K, Khanna M, Ronsard L, Meseko CA, Sanicas M (April 2018). "The emerging influenza virus threat: status and new prospects for its therapy and control". Archives of Virology. 163 (4): 831–844. doi:10.1007/s00705-018-3708-y. PMC 7087104. PMID 29322273.

- ^ "Antiviral Drug Resistance among Influenza Viruses". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 17 April 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Schwab RS, England AC, Poskanzer DC, Young RR (May 1969). "Amantadine in the treatment of Parkinson's disease". JAMA. 208 (7): 1168–1170. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03160070046011. PMID 5818715.

- ^ Schwab RS, Poskanzer DC, England AC, Young RR (November 1972). "Amantadine in Parkinson's disease. Review of more than two years' experience". JAMA. 222 (7): 792–5. doi:10.1001/jama.222.7.792. PMID 4677928.

- ^ Bastings E. "NDA 208944 Approval Letter" (PDF).

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Gocovri (amantadine extended-release)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 June 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Amantadine (International database)". Drugs.com. 5 August 2024. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ "Amantadine: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d Morris H, Wallach J (2014). "From PCP to MXE: a comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs". Drug Test Anal. 6 (7–8): 614–632. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- ^ Heal DJ, Gosden J, Smith SL (November 2018). "Evaluating the abuse potential of psychedelic drugs as part of the safety pharmacology assessment for medical use in humans". Neuropharmacology. 142: 89–115. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.049. PMID 29427652.

- ^ Nicholson KL, Jones HE, Balster RL (May 1998). "Evaluation of the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus properties of the low-affinity N-methyl-D-aspartate channel blocker memantine". Behav Pharmacol. 9 (3): 231–243. PMID 9832937.

- ^ a b Sipress A (18 June 2005). "Bird Flu Drug Rendered Useless". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ Aoki FY, Boivin G, Roberts N (2007). "Influenza virus susceptibility and resistance to oseltamivir". Antiviral Therapy. 12 (4 Pt B): 603–16. doi:10.1177/135965350701200S04.1. PMID 17944268. S2CID 25907483.

- ^ "Enforcement Report – Week of September 23, 2015". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Deutschenbaur L, Beck J, Kiyhankhadiv A, Mühlhauser M, Borgwardt S, Walter M, et al. (January 2016). "Role of calcium, glutamate and NMDA in major depression and therapeutic application". Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 64: 325–33. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.02.015. PMID 25747801.

- ^ a b c Shamabadi A, Ahmadzade A, Aqamolaei A, Mortazavi SH, Hasanzadeh A, Akhondzadeh S (July 2022). "Ketamine and Other Glutamate Receptor Modulating Agents for Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials". Iran J Psychiatry. 17 (3): 320–340. doi:10.18502/ijps.v17i3.9733. PMC 9699814. PMID 36474699.

- ^ a b Kleeblatt J, Betzler F, Kilarski LL, Bschor T, Köhler S (May 2017). "Efficacy of off-label augmentation in unipolar depression: A systematic review of the evidence". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 27 (5): 423–441. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.03.003. PMID 28318897.

- ^ Pozzi M, Bertella S, Gatti E, Peeters GG, Carnovale C, Zambrano S, et al. (December 2020). "Emerging drugs for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 25 (4): 395–407. doi:10.1080/14728214.2020.1820481. hdl:2434/851076. PMID 32938246.

- ^ Mohammadi MR, Kazemi MR, Zia E, Rezazadeh SA, Tabrizi M, Akhondzadeh S (November 2010). "Amantadine versus methylphenidate in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, double-blind trial". Human Psychopharmacology. 25 (7–8): 560–565. doi:10.1002/hup.1154. PMID 21312290. S2CID 30677758.

- ^ Morrow K, Choi S, Young K, Haidar M, Boduch C, Bourgeois JA (September 2021). "Amantadine for the treatment of childhood and adolescent psychiatric symptoms". Proceedings. 34 (5): 566–570. doi:10.1080/08998280.2021.1925827. PMC 8366930. PMID 34456474.

- ^ Płusa T (February 2021). "Przeciwzapalne działanie amantadyny i memantyny w zakażeniu SARS-CoV-2" [Anti-inflammatory effects of amantadine and memantine in SARS-CoV-2 infection]. Pol Merkur Lekarski (in Polish). 49 (289): 67–70. PMID 33713098.

- ^ Marinescu I, Marinescu D, Mogoantă L, Efrem IC, Stovicek PO (2020). "SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with serious mental illness and possible benefits of prophylaxis with Memantine and Amantadine". Rom J Morphol Embryol. 61 (4): 1007–1022. doi:10.47162/RJME.61.4.03. PMC 8343601. PMID 34171050.

External links

[edit]- Adamantanes

- Amines

- Anti-influenza agents

- Anti–RNA virus drugs

- Antiparkinsonian agents

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder management

- Dissociative drugs

- Drugs with unknown mechanisms of action

- Nicotinic antagonists

- NMDA receptor antagonists

- Nootropics

- Pro-motivational agents

- Proton channel blockers

- Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine releasing agents

- Serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- Sigma agonists

- Stimulants

- Suspected embryotoxins

- Suspected teratogens

- Antidyskinetic agents