Byzantine Armenia

Byzantine Armenia Բյուզանդական Հայաստան | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 387–536 | |||||||||

Byzantine Armenia, 387-536 | |||||||||

| Capital | Sebastia Melitene Arsamosata Theodosiopolis (Garin) 39°10′N 40°39′E / 39.17°N 40.65°E | ||||||||

| Common languages | Armenian (native language) Medieval Greek | ||||||||

| Religion | Armenian Apostolic Chalcedonian Christianity | ||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity, Early Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Established | 387 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 536 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Armenia |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Origins • Etymology |

Byzantine Armenia, sometimes known as Western Armenia,[1][2][3] is the name given to the parts of Kingdom of Armenia that became part of the Byzantine Empire. The size of the territory varied over time, depending on the degree of control the Byzantines had over Armenia.

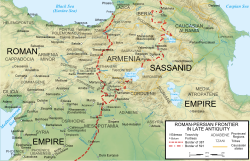

The Byzantine and Sassanid Empires divided Armenia in 387 and in 428. Western Armenia fell under Byzantine rule, and Eastern Armenia fell under Sassanid control. Even after the establishment of the Bagratid Armenian Kingdom, parts of historic Armenia and Armenian-inhabited areas were still under Byzantine rule.

The Armenians had no representation in the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451 because of their struggle against the Sassanids in an armed rebellion. That reason caused a theological drift to appear between Armenian and Byzantine Christianity.[4]

Regardless, many Armenians became successful in the Byzantine Empire. Numerous Byzantine emperors were either ethnically Armenian, half-Armenian, part-Armenian or possibly Armenian; although culturally Eastern Roman (Byzantine). The best example is Emperor Heraclius, whose father was Armenian and mother was Cappadocian. Emperor Heraclius began the Heraclian Dynasty (610–717). Basil I is another example of an Armenian beginning a dynasty; the Macedonian dynasty. His father was Armenian and his mother was Greek. Other emperors of full, or partial Armenian origin include Romanos I, John I Tzimiskes, Artabasdos, Philippikos Bardanes and Leo V.

Armenian military in the Byzantine Army

[edit]Armenia made great contributions to Byzantium through its troops of soldiers. The empire was in need of a good army as it was constantly being threatened. The army was relatively small, never exceeding 150,000 men. The military was sent to different parts of the empire, and took part in the most fierce battles and never exceeded 20,000 or 30,000 men. From the 5th century forwards the Armenians were regarded as the main constituent of the Byzantine army. Procopius recounts that the scholarii, the palace guards of the emperor, "were selected from amongst the bravest Armenians".[citation needed]

Armenian soldiers in the Byzantine army are cited during the following centuries, especially during the 9th and the 10th centuries, which might have been the period of greatest participation of the Armenians in the Byzantine army. Byzantine and Arab historians are unanimous in recognizing significance of the Armenians soldiers. Charles Diehl, for instance, writes: “The Armenian units, particularly during this period, were numerous and well trained.”[5] Another Byzantine historian praises the decisive role which the Armenian infantry played in the victories of the Byzantine emperors Nicephorus Phocas and John Tzimiskes.[6]

At that time the Armenians served side by side with the Norsemen who were in the Byzantine army. This first encounter between the Armenian mountain-dwellers and the Norse has been discussed by Nansen, who brings these two elements closer to each other and records: “It was the Armenians who together with our Scandinavian forefathers made up the assault units of Byzantine.”[7] Moreover, Bussel underlines the similarities in the way of thinking and the spirit of the Armenian feudal lords and the northern warriors. He claims that, in both groups, there was a strange absence and ignorance of government and public interest and at the same time an equally large interest in achieving personal distinctions and a loyalty towards their masters and leaders.[8]

Armenian emperors of Byzantium

[edit]The partition of the Roman Empire between the two sons of the emperor Theodosius was soon followed by a predominance of foreign elements in the court of Byzantium, the eastern half of the divided world. The proximity of the capital to Armenia attracted to the shores of the Bosporus a great number of Armenians, and for three centuries, they played a distinguished part in the history of the Eastern Empire.[9]

Council of Theodosiopolis (593)

[edit]

After the conclusion of long Byzantine-Persian War (572-591), direct Byzantine rule was extended to all western regions of Armenia. To strengthen political control over newly annexed regions, Emperor Maurice (582-602) decided to support the pro-Chalcedonian faction of the local Armenian Church. In 593, a regional council of western Armenian bishops was convened in Theodosiopolis and proclaimed full allegiance to the Chalcedonian Definition. The council also elected John (Yovhannes, or Hovhannes) of Bagaran as new Catholicos of Chalcedonian Armenians.[10]

Attitudes towards Armenians

[edit]This poem by Kasia reflects the prevailing tensions and biases within the Byzantine Roman Empire against citizens of non-Roman origins, particularly towards Armenians, who were often viewed unfavorably by segments of Byzantine Roman society.

"The terrible race of the Armenians is deceitful and extremely vile, fanatical, deranged, and malignant, puffed up with hot air and full of slyness. A wise man said correctly about them that Armenians are vile when they live in obscurity, even more vile when they become famous, and most vile in all ways when they become rich. When they become filthy rich and honored, then to all they seem as vileness heaped upon vileness."[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rivoira, Giovanni Teresio (1918). Moslem Architecture: Its Origins and Development. Oxford University Press. p. 188.

- ^ The Armenian Review, Volume 3. Boston: Hairenik Association. 1950. p. 25.

- ^ Baumstark, Anton (2011). On the Historical Development of the Liturgy. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780814660966.

- ^ "The Glory of Byzantium | Publications for Educators | Explore & Learn | The Metropolitan Museum of Art".

- ^ C. Diehl, The Cambridge Medieval History, vol. IV; See also Schlumberger, Un Emperor byzantin au X siecle, Paris, 1890, p. 83 and 350

- ^ F. W. Bussel, Essays on the Constitutional History of the Roman Empire, London, 1910, vol. II, p. 234

- ^ F. Nansen, Gjennem Armenia, Oslo, 1927, p. 21; See also Pawlikowski-Cholwa, Heer und Völkerschicksal, München, 1936, p. 117

- ^ F. W. Bussel, Essays on the Constitutional History of the Roman Empire, London, 1910, vol. II, p. 448

- ^ Vahan Kurkjian - Armenians Outside of Armenia

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 108-109, 284, 343.

- ^ Kaldellis, Anthony (2019-04-01). Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium. Harvard University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-674-98651-0.

Sources

[edit]- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in History. Vol. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410563.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Kaegi, Walter E. (1992). Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41172-6.