Burma Road (Israel)

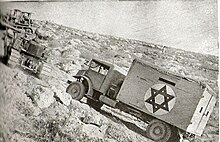

Burma Road (Hebrew: דרך בורמה Derekh Burma) in Israel was a makeshift bypass road between Kibbutz Hulda and Jerusalem, built under the supervision of General Mickey Marcus during the 1948 Siege of Jerusalem. It was named for the Chinese Burma Road.

History

During the early phase of the 1948 Palestine war (from November 29, 1947 to May 15, 1948), local Arab forces took control of the hills overlooking the road to Jerusalem (Highway 1), between Sha'ar HaGai (Bab el-Wad) and Al-Qastal, in effect besieging the city's Jewish population. Vehicles attempting to use the road, Jerusalem's only link to the coast, took heavy fire. Convoys carrying food, weapons, and medical supplies sent by the Yishuv sustained heavy losses, and often did not get through to the city.

On May 15, 1948, British forces withdrew from the Latrun monastery and police fort that dominated the road and prevented supplies from reaching Jerusalem. Latrun was immediately occupied by the Palmach's Harel Brigade. However, on the night of May 18, British-officered Arab Legion forces from Transjordan seized Latrun, and subsequent Jewish attempts to gain a foothold in the region failed.

The growing need for supplies among Jerusalem's Jewish population weakened the Jewish foothold within the city considerably. A small amount of supplies, mostly munitions, were ferried by air, but the shortage of food, water, fuel and medicines was acute. The Jewish leadership, under David Ben-Gurion, feared that the city would surrender to the Arab Legion, and a search for a way to bypass the Arab blockade commenced.

Construction

The road ran from just east of Dayr Muhaysin (today Moshav Beko'a), by way of Bayt Jiz and Bayt Susin (near kibbutz Harel), and then crossed the road that is now known as Highway 38. From there it ascended to Bayt Mahsir (Beit Meir), Saris (Shoresh and Sho'eva), and then connected with the old Jerusalem road.[1]

Several Israeli attempts to take the Arab Legion's position in Latrun failed, but surrounding parts of the road were cleared of snipers by the end of May. Jaques Bar[who?] saw that fire from the Latrun fort could be avoided by building another road screened from its Ordnance QF 25 pounder guns, allowing truck convoys to reach Jerusalem. When 150 troops moved on foot from Hulda to Harel Brigade headquarters near Abu Ghosh, that suggested that it would be possible to modify the "gazelle path" they followed, to be hidden from the Latrun fort and accommodate vehicular traffic.

The major problem was a very steep section at the beginning of the ascent. After two weeks some supplies came through using mules and 200 men from the Home Guard (Mishmar Ha'am) to cover three miles which were impassable to vehicles. These men, mostly conscripts in their fifties, each carried a 45-pound load and made the trip twice a night. This effort lasted for five nights.

On the night of May 30–31, an attempt failed when the lead jeep overturned. The road was improved slightly. A second attempt on the following night succeeded. On the night of June 1–2 the vehicles returned, and with them was a group from Jerusalem in three jeeps. The jeep party went on to Tel Aviv to organize a supply convoy for Jerusalem, which returned that night. However, the road was still practically impassable. Vehicles had to be pushed by hand through long sections. Porters and donkeys were used to bring supplies to Jerusalem while bulldozers and road workers moved critical parts of the road out of the line of sight of Jordanian artillery and widened it. The Arab Legion spotted the activity and Jordanian artillery shelled the road, but ineffectively, since it could not be seen. Arab sharpshooters killed several road workers, and an attack on June 9 left eight Israelis dead.

Three weeks later, 10 June, the steepest section was opened to vehicles, though they needed assistance from tractors to get up it. The road allowed passage of a convoy without leaving the vehicles on June 10, in time for the UN-imposed cease fire, but it required repair as vehicular passage opened new pot holes. The road was finally completed on June 14, and water and fuel pipes were laid alongside it.[2][3] Amos Horev, later President of Technion, was an Operations Officer, and was instrumental in creating the road.[4][5] By the end of June the usual nightly convoy delivered 100 tons of supplies a night.[6] Harry Levin, in his diary entry for 7 June, wrote that 12 tons a night were getting through and he estimated that the city needed 17 tons daily. On 28 July he noted that during the first truce, 11 June to 8 July, 8,000 truckloads arrived.[7] This remained the sole supply route for several months, until the opening of the Valor Road (Kvish Hagevurah).

In popular culture

The 1966 film Cast a Giant Shadow, which dramatizes the career of Mickey Marcus, has a major part dedicated to the construction of the Burma Road.

The 2006 film O Jerusalem includes scenes in which food and supplies are brought into Jerusalem on what would become the Burma Road.

See also

References

- ^ Shamir, Shlomo (1994). בכל מחיר – לירושלים [To Jerusalem – at Any Cost] (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Ma'arachot. pp. 417–418.

- ^ Isseroff, Ami (September 2008). "Burma Road". Zionism & Israel. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ Rosenbloom, Michael (December 2001). "The Road to Jerusalem". Tales of Survival. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ Dan Kurzman (1998). Soldier of peace: the life of Yitzhak Rabin, 1922–1995. HarperCollins. p. 131. ISBN 0-06-018684-4. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Ben Dunkelman (1984). Dual Allegiance: An Autobiography. Formac Publishing Company. p. 229. ISBN 0-88780-127-7. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Joseph, pages 155,156.

- ^ Levin, pages 236, 273.