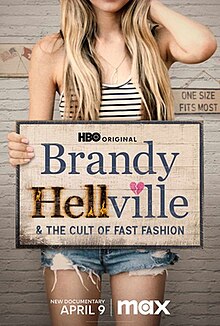

Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion

| Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Eva Orner |

| Based on | Reporting by Kate Taylor |

| Distributed by | HBO |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion is a 2024 documentary film directed by Eva Orner, focused on the business practices of clothing brand Brandy Melville. The film is based on Kate Taylor's reporting for Insider.

Background

[edit]Italian clothing brand Brandy Melville was founded in the 1980s,[1] and maintains 95 retail locations[2] in more than 15 countries.[1] It opened its first store in the United States in 2009, targeting Westwood, Los Angeles, near the campus of UCLA.[2] In the 2010s, the brand became extremely popular among girls and young women in the United States,[3] where it now has 40 stores.[2]

As reported by The Cut, the brand is associated with "Americana décor and string lights, dotted with beachy wooden signs and staffed with thin, intentionally good-looking, blonde girls".[3] Employees are generally girls about 16 years old.[4] Brandy Melville generally manufactures clothing marketed as one-size-fits-all, and has been criticized as exclusive of many body shapes; the branding was changed to "one size fits most" in response to public backlash.[3] This one size roughly corresponds to a typical XS or S in the United States.[2] The brand has also been accused of copying the work of independent clothing designers, and Forever 21 filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against them in 2016.[5]

After Kate Taylor published an article for Insider about Brandy Melville's alleged malpractice[3] in 2021,[5] the brand issued no apology and faced no financial repercussions. Its market has continued to expand, particularly in China, where its sizing is even smaller. A viral "BM challenge" in China encourages girls to lose weight so they can wear a Brandy Melville skirt.[3]

Synopsis

[edit]Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion focuses on the business practices of Brandy Melville, detailing allegations of antisemitism, discrimination based on weight, inappropriate interactions with minors, racism, and sexual assault. Many of these accusations center on Brandy Melville's founder and chief executive officer, Stephan Marsan. The documentary includes interviews with various people affiliated with the company, including former employees.[3] The allegations of bigotry are interspersed with discussion of the brand's fast fashion status.[5]

Brandy Hellville ends with a request for people to boycott Brandy Melville.[6]

Allegations of bigotry

[edit]The film describes allegations by journalist Kate Taylor and former employees that Marsan consistently acted in a racist and body-shaming manner toward employees. These include claims that White employees were commonly given public-facing roles in stores while people of color were assigned to tasks in the back,[3][5] and Asian people were specifically assigned to work the register;[7] Taylor states that two racism-related lawsuits have been filed against Brandy Melville.[3]

Former employees also allege that they were made to feel bad about their bodies, that some employees were explicitly offered jobs or fired because of their body shape, and that employees were made to take full-body photos of themselves at the start of each shift, sending them to Marsan and an assistant who ran the brand's Instagram page. One employee states that Marsan saved some of these photos in a file, and another reported having received requests for employees' "chest and feet"[3] to be included in the full-body photos.[6] A former vice president says in an interview that Marsan fired employees whose photos he didn't like. Multiple employees say that they had eating disorders while working for Brandy Melville.[3] Multiple executives allege that Marsan viewed the brand's "one size fits most" policy as a way to maintain its exclusivity, and that he was happy that it was being criticized.[5]

They’re not hypocrites because they’re exactly who they say they are. They’re just racist sexist pigs.

Two former associates of Brandy Melville state in interviews that antisemitic, misogynistic, and racist jokes were sent in a large company group chat called "Brandy Melville Gags," including an image of Marsan dressed as Adolf Hitler and photos of him mocking Black people.[3] A screenshot included in the documentary shows an emaciated woman wearing a sash with the words "Miss Auschwitz, 1943." A former store owner states that members of the Italian manufacturing division and store owners were in the chat, as well as Marsan and his brother.[5]

In the film, former employees also allege that Marsan, a self-described libertarian, discussed politics with his young female employees and routinely became upset when many of them supported Bernie Sanders. He also allegedly distributed copies of Atlas Shrugged, a novel by Ayn Rand that supports capitalism. A private label of Brandy Melville is named John Galt, after a character in Atlas Shrugged.[3]

Sexual assault allegations

[edit]Taylor reports on an alleged sexual assault at the "Brandy apartment" in SoHo, Manhattan. Former Brandy Melville employees who stayed at the apartment state that men would unexpectedly enter and sometimes stay overnight. In a hospital report, a 21-year-old employee alleged that after being offered the apartment as a place to stay while in the United States on a visa, she went drinking with an older Italian man who was unexpectedly also staying in the apartment. After having two drinks, she reported that her memory lapsed and she woke up naked in the apartment. The hospital report stated that she had been "raped by her boss and didn’t want to report it" because she was afraid she would have to leave the United States if she lost her job.[3]

Fast fashion

[edit]In some cases, the names of these things on the Brandy Melville website, [they'll] be like Jocelyn shirt. And it'll be because this shirt was literally purchased off of Jocelyn's back.

The film additionally characterizes Brandy Melville as a fast fashion company. It alleges that while clothing "Made in Italy" is often considered luxurious in the United States, the brand's clothing is likely manufactured in fast fashion facilities in Prato.[3] Matteo Biffoni, the mayor of Prato, says in an interview that there are several fast fashion factories in Prato, and that some use unethical labor practices.[5] The documentary also states that the business model of Brandy Melville sometimes involves making near-exact copies of clothing purchased elsewhere by employees,[3] and former employees allege that executives sometimes offered to purchase the outfits the employees were wearing so the brand could copy and manufacture them.[5] It also describes the way many items of fast fashion clothing end up in Accra where they are resold[3] or dumped and end up in the ocean and on beaches.[4]

Taylor discusses the corporate structure of Brandy Melville, which Orner describes as unusually "chaotic". Taylor states that a different shell corporation owns each of the brand's stores, and the trademark is owned by a company in Switzerland, a structure Orner characterizes as "not meant to be traceable".[4] Taylor also says that Marsan himself has virtually no presence on the Internet.[5]

Production

[edit]Brandy Hellville was directed by Eva Orner, based on reporting by Kate Taylor for Insider.[3] Orner states that she had not heard of Brandy Melville until 2022, when producers suggested the brand as a topic for an investigatory documentary film.[5]

I’ve done a lot of stuff in war zones, and with refugees and really life-or-death situations, and people have been more comfortable being on camera.

According to the filmmakers, Stephan Marsan declined to be interviewed for the documentary. Orner stated that it was difficult to find former employees to interview because many were afraid of potential repercussions,[5] and because many employees worked for Brandy Melville when they were very young, meaning they are now "young women embarking on careers or in their twenties".[1] Former employees are identified only by their first names.[5]

The film premiered at South by Southwest[4] and was released on HBO on April 9, 2024.[5] It has a runtime of 91 minutes.[4]

Reception

[edit]A review in The New York Times noted that documentaries with similar topics have been made before, citing White Hot: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch as one example. However, the reviewer stated that the documentary was set apart by its engagement with the idea that Brandy Melville is in some ways cultlike, although they found that this was "underdeveloped" over the course of the film.[8]

Reviewing Brandy Hellville for NPR alongside two other "eye-opening documentaries", Linda Holmes summarized the narrative as "the story of how social media helped make a juggernaut out of a whole lot of nondescript tiny shirts". She expressed appreciation for the discussion of "gross in-store culture", also comparing the documentary to White Hot, but noted that she wished for more focus on the brand's involvement with fast fashion.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Moorman, Taijuan (April 11, 2024). "'Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion' doc examines controversial retailer Brandy Melville". USA TODAY. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Lang, Cady (April 12, 2024). "HBO's Brandy Melville Doc Reveals the Dark Side of Fast Fashion". TIME. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Issawi, Danya (April 11, 2024). "The Most Messed-up Findings in the Brandy Melville Documentary". The Cut. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Horton, Adrian (April 9, 2024). "'A very odd and ugly worldview': the dark side of fast fashion brand Brandy Melville". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Holtermann, Callie (April 10, 2024). "'Brandy Hellville & the Cult of Fast Fashion': 5 Takeaways". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 10, 2024. Retrieved April 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Rodgers, Daniel (April 12, 2024). "The 5 Most Harrowing Revelations From HBO's Brandy Melville Documentary". Vogue. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Jones, C. T. (April 13, 2024). "'Brandy Hellville': The Allegations Against the Cult Gen-Z Fashion Brand". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ Wilkinson, Alissa (April 12, 2024). "'Brandy Hellville': A New Twist for Cult Documentaries". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 13, 2024. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ Holmes, Linda (April 14, 2024). "Three eye-opening documentaries you can stream right now". NPR. Retrieved April 14, 2024.