Boston: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 142.33.165.252 to version by Jckcrll. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1004221) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 266: | Line 266: | ||

From May to September, the city experiences thunderstorms that are occasionally severe; large [[hail]], damaging winds and heavy downpours accompany such severe events. Although downtown Boston has never been struck by a violent [[tornado]], the city itself has seen its fair share of [[tornado warning]]s, but damaging storms are more common to areas north, west, and northwest of the city. |

From May to September, the city experiences thunderstorms that are occasionally severe; large [[hail]], damaging winds and heavy downpours accompany such severe events. Although downtown Boston has never been struck by a violent [[tornado]], the city itself has seen its fair share of [[tornado warning]]s, but damaging storms are more common to areas north, west, and northwest of the city. |

||

{{-}} |

{{-}} |

||

{{Boston weatherbox}} |

{{Boston weatherbox}}jeremy likes boys |

||

==Demographics== |

==Demographics== |

||

Revision as of 15:47, 11 April 2012

Boston | |

|---|---|

| City of Boston | |

Clockwise: Skyline of Back Bay seen from the Charles River, Fenway Park, Christian Science Church, Boston Common and the Downtown Crossing skyline, skyline of the Financial District seen from the Boston Harbor, and Massachusetts State House | |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): Sicut patribus sit Deus nobis (Latin "As God was with our fathers, so may He be with us") | |

Location in Suffolk County, Massachusetts | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Suffolk |

| Settled | September 17, 1630 |

| Incorporated (city) | March 4, 1822 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor – council |

| • Mayor | Thomas M. Menino (D) |

| Area | |

| • State Capital | 89.63 sq mi (232.14 km2) |

| • Land | 48.43 sq mi (125.43 km2) |

| • Water | 41.21 sq mi (106.73 km2) |

| • Urban | 1,774 sq mi (4,595 km2) |

| • Metro | 4,511 sq mi (11,683 km2) |

| • CSA | 10,644 sq mi (27,568 km2) |

| Elevation | 141 ft (43 m) |

| Population | |

| • State Capital | 617,594 ('10 census) |

| • Density | 12,752/sq mi (4,924/km2) |

| • Urban | 4,032,484 ('00 census) |

| • Metro | 4,522,858 ('08 est.) |

| • CSA | 7,609,358 ('09 est.) |

| • Demonym | Bostonian |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 53 total ZIP codes:[10]

|

| Area code(s) | 617 and 857 |

| FIPS code | 25-07000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0617565 |

| Website | www.cityofboston.gov |

Boston (pronounced /ˈbɔstən/ ) is the capital of and largest city in Massachusetts,[11] and is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The largest city in New England, Boston is regarded as the unofficial "Capital of New England" for its economic and cultural impact on the entire New England region.[12] The city proper, covering just 48.43 square miles, had a population of 617,594 according to the 2010 U.S. Census.[6] Boston is also the anchor of a substantially larger metropolitan area called Greater Boston, home to 4.5 million people and the tenth-largest metropolitan area in the country.[8] Greater Boston as a commuting region[13] is home to 7.6 million people, making it the fifth-largest Combined Statistical Area in the United States.[9][14]

In 1630, Puritan colonists from England founded the city on the Shawmut Peninsula.[15] During the late 18th century, Boston was the location of several major events during the American Revolution, including the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party. Several early battles of the American Revolution, such as the Battle of Bunker Hill and the Siege of Boston, occurred within the city and surrounding areas. Through land reclamation and municipal annexation, Boston has expanded beyond the peninsula. After American independence was attained Boston became a major shipping port and manufacturing center,[15] and its rich history now helps attract many tourists, with Faneuil Hall alone attracting over 20 million every year.[16] The city was the site of several firsts, including America's first public school, Boston Latin School (1635),[17] and the first subway system in the United States (1897).[18]

With many colleges and universities within the city and surrounding area, Boston is an international center of higher education and a center for medicine.[19] The city's economic base includes research, manufacturing, finance, and biotechnology.[20] As a result, the city is a leading finance center, ranking 12th in the Z/Yen top 20 Global Financial Centers.[21] The city was also ranked number one for innovation, both globally and in North America,[22] for a variety of reasons.[23][24] Boston has one of the highest costs of living in the United States,[25] though it remains high on world livability rankings, ranking third in the US and 36th globally.[26]

History

Boston was founded on September 17, 1630, by Puritan colonists from England.[15] The Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony are sometimes confused with the Pilgrims, who founded Plymouth Colony ten years earlier in what is today Bristol County, Plymouth County, and Barnstable County, Massachusetts. The two groups, which differed in religious practice, are historically distinct. The separate colonies were not united until the formation of the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1691.

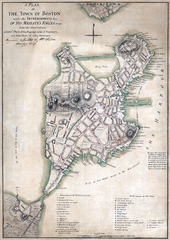

The Shawmut Peninsula was connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus and was surrounded by the waters of Massachusetts Bay and the Back Bay, an estuary of the Charles River. Several prehistoric Native American archaeological sites that were excavated in the city have shown that the peninsula was inhabited as early as 5000 BC.[27] Boston's early European settlers first called the area Trimountaine, but later renamed the town after Boston in Lincolnshire, England, from which several prominent colonists had emigrated. Massachusetts Bay Colony's original governor, John Winthrop, gave a famous sermon entitled "A Model of Christian Charity", popularly known as the "City on a Hill" sermon, which espoused the idea that Boston had a special covenant with God. (Winthrop also led the signing of the Cambridge Agreement, which is regarded as a key founding document of the city.) Puritan ethics molded a stable and well-structured society in Boston. For example, shortly after Boston's settlement, Puritans founded America's first public school, Boston Latin School (1635),[17] and America's oldest school in continuous existence, Roxbury Latin School (1645). Over the next 130 years, Boston participated in four French and Indian Wars, until the British defeated the French and their native allies in North America. Boston was the largest town in British North America until Philadelphia grew larger in the mid 18th century.[28]

In the 1770s, British attempts to exert more-stringent control on the thirteen colonies—primarily via taxation—led to the American Revolution.[15] The Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party, and several early battles—including the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the Battle of Bunker Hill, and the Siege of Boston—occurred in or near the city. During this period, Paul Revere made his famous midnight ride. After the Revolution, Boston had become one of the world's wealthiest international trading ports because of the city's consolidated seafaring tradition. Exports included rum, fish, salt, and tobacco.[29] During this era, descendants of old Boston families were regarded as the nation's social and cultural elites; they were later dubbed the Boston Brahmins.[30]

The Embargo Act of 1807, adopted during the Napoleonic Wars, and the War of 1812 significantly curtailed Boston's harbor activity. Although foreign trade returned after these hostilities, Boston's merchants had found alternatives for their capital investments in the interim. Manufacturing became an important component of the city's economy, and by the mid-19th century, the city's industrial manufacturing overtook international trade in economic importance. Until the early 20th century, Boston remained one of the nation's largest manufacturing centers and was notable for its garment production and leather-goods industries.[16] A network of small rivers bordering the city and connecting it to the surrounding region made for easy shipment of goods and led to a proliferation of mills and factories. Later, a dense network of railroads facilitated the region's industry and commerce. From the mid-19th to late 19th century, Boston flourished culturally. It became renowned for its rarefied literary culture and lavish artistic patronage. It also became a center of the abolitionist movement.[31]

The city reacted strongly to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850,[32] which contributed to President Franklin Pierce's attempt to make an example of Boston after the Burns Fugitive Slave Case.[33][34]

In 1822,[35] the citizens of Boston voted to change the official name from "the Town of Boston" to "the City of Boston", and on March 4, 1822, the people of Boston accepted the charter incorporating the City.[36] At the time Boston was chartered as a city, the population was about 46,226, while the area of the city was only 4.7 square miles (12 km2).[36] In the 1820s, Boston's population began to swell, and the city's ethnic composition changed dramatically with the first wave of European immigrants. Irish immigrants dominated the first wave of newcomers during this period, especially following the Irish potato famine. By 1850, about 35,000 Irish lived in Boston.[37] In the latter half of the 19th century, the city saw increasing numbers of Irish, Germans, Lebanese, Syrians,[38] French Canadians, and Russian and Polish Jews settle in the city. By the end of the 19th century, Boston's core neighborhoods had become enclaves of ethnically distinct immigrants—Italians inhabited the North End, Irish dominated South Boston and Charlestown, and Russian Jews lived in the West End. Irish and Italian immigrants brought with them Roman Catholicism. Currently, Catholics make up Boston's largest religious community,[39] and since the early 20th century, the Irish have played a major role in Boston politics—prominent figures include the Kennedys, Tip O'Neill, and John F. Fitzgerald.[30]

Between 1631 and 1890, the city tripled its physical size by land reclamation—by filling in marshes, mud flats, and gaps between wharves along the waterfront[40] —a process that Walter Muir Whitehill called "cutting down the hills to fill the coves". The largest reclamation efforts took place during the 19th century. Beginning in 1807, the crown of Beacon Hill was used to fill in a 50-acre (20 ha) mill pond that later became the Haymarket Square area. The present-day State House sits atop this lowered Beacon Hill. Reclamation projects in the middle of the century created significant parts of the South End, the West End, the Financial District, and Chinatown. After The Great Boston Fire of 1872, workers used building rubble as landfill along the downtown waterfront. During the mid-to-late 19th century, workers filled almost 600 acres (2.4 km2) of brackish Charles River marshlands west of Boston Common with gravel brought by rail from the hills of Needham Heights. Also, the city annexed the adjacent towns of South Boston (1804), East Boston (1836), Roxbury (1868), Dorchester (including present day Mattapan and a portion of South Boston) (1870), Brighton (including present day Allston) (1874), West Roxbury (including present day Jamaica Plain and Roslindale) (1874), Charlestown (1874), and Hyde Park (1912).[41][42] Other proposals, for the annexation of Brookline, Cambridge,[43] and Chelsea,[44][45] have been unsuccessful.

On January 15, 1919, in the North End neighborhood, a large molasses storage tank burst, and a wave of molasses rushed through the streets at an estimated 35 mph (56 km/h), killing 21 and injuring 150. The event has entered local folklore, known as The Boston Molasses Disaster.[46]

By the early and mid-20th century, the city was in decline as factories became old and obsolete, and businesses moved out of the region for cheaper labor elsewhere.[15] Boston responded by initiating various urban renewal projects under the direction of the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), which was established in 1957. In 1958, BRA initiated a project to improve the historic West End neighborhood. Extensive demolition was met with vociferous public opposition.[47] BRA subsequently reevaluated its approach to urban renewal in its future projects, including the construction of Government Center. In 1965, the first Community Health Center in the United States opened, the Columbia Point Health Center, in the Dorchester neighborhood. It mostly served the massive Columbia Point public housing complex adjoining it, which was built in 1953. The health center is still in operation and was rededicated in 1990 as the Geiger-Gibson Community Health Center.[48]

By the 1970s, the city's economy boomed after 30 years of economic downturn. A large number of high rises were constructed in the Financial District and in Boston's Back Bay during this time period. This boom continued into the mid-1980s and later began again. Boston now has the second largest skyline in the Northeast (after New York) in terms of the number of buildings reaching a height of over 500 feet (150 m). Hospitals such as Massachusetts General Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Brigham and Women's Hospital lead the nation in medical innovation and patient care. Schools such as Boston University, the Harvard Medical School, Northeastern University, Wentworth Institute of Technology and Boston Conservatory attract students to the area. Nevertheless, the city experienced conflict starting in 1974 over desegregation busing, which resulted in unrest and violence around public schools throughout the mid-1970s. In 1984, the City of Boston gave control of the Columbia Point public housing complex to a private developer, who redeveloped and revitalized the property from its rundown and dangerous state into an attractive residential mixed-income community called Harbor Point Apartments, which opened in 1988 and was completed by 1990. It was the first federal housing project to be converted to private, mixed-income housing in the United States, and served as a model for the federal HUD HOPE VI public housing revitalization program that began in 1992.[49]

In the early 21st century, the city has become an intellectual, technological, and political center. It has, however, experienced a loss of regional institutions,[51] which included the acquisition of The Boston Globe by The New York Times, and the loss to mergers and acquisitions of local financial institutions such as FleetBoston Financial, which was acquired by Charlotte-based Bank of America in 2004. Boston-based department stores Jordan Marsh and Filene's have both been merged into the New York–based Macy's. Boston has also experienced gentrification in the latter half of the 20th century,[52] with housing prices increasing sharply since the 1990s.[25] Living expenses have risen, and Boston has one of the highest costs of living in the United States,[53] and was ranked the 99th most expensive major city in the world in a 2008 survey of 143 cities.[54] Despite cost of living issues, Boston ranks high on livability ratings, ranking 36th worldwide in quality of living in 2011 in a survey of 221 major cities.[55]

Geography

Owing to its early founding, Boston is very compact. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 89.6 square miles (232.1 km2)—48.4 square miles (125.4 km2) (54.0%) of land and 41.2 square miles (106.7 km2) (46.0%) of water. Boston is the country's third most densely populated city that is not a part of a larger city's metropolitan area.[56] This is largely attributable to the rarity of annexation by New England towns. Boston is surrounded by the "Greater Boston" region and is bordered by the cities and towns of Winthrop, Revere, Chelsea, Everett, Somerville, Cambridge, Watertown, Newton, Brookline, Needham, Dedham, Canton, Milton, and Quincy. The Charles River separates Boston proper from Cambridge, Watertown, and the neighborhood of Charlestown. To the east lies Boston Harbor and the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area (BHINRA). This includes part of the city's territory, specifically Calf Island, Gallops Island, Great Brewster Island, Green Island, Little Brewster Island, Little Calf Island, Long Island, Lovells Island, Middle Brewster Island, Nixes Mate, Outer Brewster Island, Rainsford Island, Shag Rocks, Spectacle Island, The Graves, and Thompson Island. The Neponset River forms the boundary between Boston's southern neighborhoods and the city of Quincy and the town of Milton.[57] The Mystic River separates Charlestown from Chelsea and Everett, and Chelsea Creek and Boston Harbor separate East Boston from Boston proper.[58] Boston's official elevation, as measured at Logan International Airport, is 19 ft (5.8 m) above sea level.[59] The highest point in Boston is Bellevue Hill at 330 ft (101 m) above sea level, and the lowest point is at sea level.[60] Boston is the only state capital in the contiguous United States with an ocean coastline.

Much of the Back Bay and South End neighborhoods are built on reclaimed land—all of the earth from two of Boston's three original hills, the "Trimountain", was used as landfill material. Pemberton Hill, which would become Pemberton Square in the Government Center neighborhood, and Mount Vernon, were leveled completely. Only Beacon Hill—the smallest of the three original hills—remains partially intact; only half of its height was cut down for landfill. Tremont Street is named after the three hills. The downtown area and immediate surroundings consist mostly of low-rise brick or stone buildings, with many older buildings in the Federal style. Several of these buildings mix in with modern high-rises, notably in the Financial District, Government Center, the South Boston waterfront, and Back Bay, which includes many prominent landmarks such as the Boston Public Library, Christian Science Center, Copley Square, Newbury Street, and New England's two tallest buildings—the John Hancock Tower and the Prudential Center.[61]

Near the John Hancock Tower is the old John Hancock Building with its prominent weather forecast beacon—the color of the illuminated light gives an indication of weather to come: "steady blue, clear view; flashing blue, clouds are due; steady red, rain ahead; flashing red, snow instead". (In the summer, flashing red indicates instead that a Red Sox game has been rained out.) Smaller commercial areas are interspersed among single-family homes and wooden/brick multi-family row houses. Currently, the South End Historic District remains the largest surviving contiguous Victorian-era neighborhood in the U.S.[62] Along with downtown, the geography of South Boston was particularly impacted by the Central Artery/Tunnel (CA/T) Project (or the "Big Dig"). The unstable reclaimed land in South Boston posed special problems for the project's tunnels. In the downtown area, the CA/T Project allowed for the removal of the unsightly elevated Central Artery and the incorporation of new green spaces and open areas.

Boston Common, located near the Financial District and Beacon Hill, is the oldest public park in the United States.[64] Along with the adjacent Boston Public Garden, it is part of the Emerald Necklace, a string of parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted to encircle the city. Jamaica Pond, part of the Emerald Necklace, is the largest body of freshwater in the city. Franklin Park, which is also part of the Emerald Necklace, is the city's largest park and houses the Franklin Park Zoo.[65] Another major park is the Esplanade, located along the banks of the Charles River. The Hatch Shell, an outdoor concert venue, is located adjacent to the Charles River Esplanade. Other parks are scattered throughout the city, with the major parks and beaches located near Castle Island (not part of the BHINRA, and now connected to the mainland); in Charlestown; and along the Dorchester, South Boston, and East Boston shorelines.

Neighborhoods

Boston is sometimes called a "city of neighborhoods" because of the profusion of diverse subsections. There are 21 official neighborhoods in Boston used by the city.[66] These neighborhoods include: Allston/Brighton, Back Bay, Bay Village, Beacon Hill, Charlestown, Chinatown/Leather District, Dorchester, Downtown/Financial District, East Boston, Fenway/Kenmore, Hyde Park, Jamaica Plain, Mattapan, Mission Hill, North End, Roslindale, Roxbury, South Boston, South End, West End, and West Roxbury.

Climate

Boston has a climate that is continental in nature but with maritime influences owing to its coastal location, a phenomenon common to coastal southern New England. The climate is either classified as a humid subtropical climate (Koppen Cfa), using the −3 °C (26.6 °F) isotherm of the original Köppen scheme, or a humid continental climate (Koppen Dfb with areas of Dfa), using the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm preferred by some climatologists.

Summers are typically warm, rainy, and humid, while winters are cold, windy, and snowy. Spring and fall are usually mild, but conditions are widely varied, depending on wind direction and jet stream positioning. Prevailing wind patterns that blow offshore affect Boston, minimizing the influence of the Atlantic Ocean.

The hottest month is July, with a mean temperature of 73.9 °F (23.3 °C). The coldest month is January, with a mean of 29.3 °F (−1.5 °C). Periods exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) in summer and below 10 °F (−12 °C) in winter are not uncommon but rarely extended, with about 13 days per year seeing the former extreme,[67] and the most recent subzero reading occurring on January 24, 2011.[68] Extremes have ranged from −18 to 104 °F (−28 to 40 °C), recorded on February 9, 1934 and July 4, 1911, respectively.[68]

Boston's coastal location on the North Atlantic, although it moderates temperatures, also makes the city very prone to Nor'easter weather systems that can produce much snow and rain.[69] The city averages 42.5 inches (1,080 mm) of precipitation a year, with 41.8 inches (106 cm) of snowfall a year. Snowfall increases dramatically as one goes inland away from the city (especially north and west of the city)—away from the warming influence of the ocean.[70] Most snowfall occurs from December through March. There is usually little or no snow in April and November, and snow is rare in May and October.[71][72]

Fog is prevalent, particularly in spring and early summer, and the occasional tropical storm or hurricane can threaten the region, especially in early autumn. Due to its situation along the North Atlantic, the city is often subjected to sea breezes, especially in the late spring, when water temperatures are still quite cold and temperatures at the coast can be more than 20 °F (11 °C) colder than a few miles inland, sometimes dropping by that amount near midday.[73][74] From May to September, the city experiences thunderstorms that are occasionally severe; large hail, damaging winds and heavy downpours accompany such severe events. Although downtown Boston has never been struck by a violent tornado, the city itself has seen its fair share of tornado warnings, but damaging storms are more common to areas north, west, and northwest of the city.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

73 (23) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

97 (36) |

100 (38) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

76 (24) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.3 (14.6) |

57.9 (14.4) |

67.0 (19.4) |

79.9 (26.6) |

88.1 (31.2) |

92.2 (33.4) |

95.0 (35.0) |

93.7 (34.3) |

88.9 (31.6) |

79.6 (26.4) |

70.2 (21.2) |

61.2 (16.2) |

96.4 (35.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.8 (2.7) |

39.0 (3.9) |

45.5 (7.5) |

56.4 (13.6) |

66.5 (19.2) |

76.2 (24.6) |

82.1 (27.8) |

80.4 (26.9) |

73.1 (22.8) |

62.1 (16.7) |

51.6 (10.9) |

42.2 (5.7) |

59.3 (15.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 29.9 (−1.2) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

38.3 (3.5) |

48.6 (9.2) |

58.4 (14.7) |

68.0 (20.0) |

74.1 (23.4) |

72.7 (22.6) |

65.6 (18.7) |

54.8 (12.7) |

44.7 (7.1) |

35.7 (2.1) |

51.9 (11.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 23.1 (−4.9) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

40.8 (4.9) |

50.3 (10.2) |

59.7 (15.4) |

66.0 (18.9) |

65.1 (18.4) |

58.2 (14.6) |

47.5 (8.6) |

37.9 (3.3) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

44.5 (6.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 4.8 (−15.1) |

8.3 (−13.2) |

15.6 (−9.1) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

41.2 (5.1) |

49.7 (9.8) |

58.6 (14.8) |

57.7 (14.3) |

46.7 (8.2) |

35.1 (1.7) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

13.1 (−10.5) |

2.6 (−16.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −13 (−25) |

−18 (−28) |

−8 (−22) |

11 (−12) |

31 (−1) |

41 (5) |

50 (10) |

46 (8) |

34 (1) |

25 (−4) |

−2 (−19) |

−17 (−27) |

−18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.39 (86) |

3.21 (82) |

4.17 (106) |

3.63 (92) |

3.25 (83) |

3.89 (99) |

3.27 (83) |

3.23 (82) |

3.56 (90) |

4.03 (102) |

3.66 (93) |

4.30 (109) |

43.59 (1,107) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 14.3 (36) |

14.4 (37) |

9.0 (23) |

1.6 (4.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.7 (1.8) |

9.0 (23) |

49.2 (125) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.8 | 10.6 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 11.8 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 11.9 | 128.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.6 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 23.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 62.3 | 62.0 | 63.1 | 63.0 | 66.7 | 68.5 | 68.4 | 70.8 | 71.8 | 68.5 | 67.5 | 65.4 | 66.5 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 16.5 (−8.6) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

33.6 (0.9) |

45.0 (7.2) |

55.2 (12.9) |

61.0 (16.1) |

60.4 (15.8) |

53.8 (12.1) |

42.8 (6.0) |

33.4 (0.8) |

22.1 (−5.5) |

38.9 (3.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 163.4 | 168.4 | 213.7 | 227.2 | 267.3 | 286.5 | 300.9 | 277.3 | 237.1 | 206.3 | 143.2 | 142.3 | 2,633.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 56 | 57 | 58 | 57 | 59 | 63 | 65 | 64 | 63 | 60 | 49 | 50 | 59 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961−1990)[76][77][78] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[79] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Boston, Massachusetts | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 41.3 (5.2) |

38.1 (3.4) |

38.4 (3.5) |

43.1 (6.2) |

49.2 (9.5) |

58.4 (14.7) |

65.7 (18.7) |

67.9 (20.0) |

64.8 (18.2) |

59.4 (15.3) |

52.3 (11.3) |

46.6 (8.2) |

52.1 (11.2) |

| Source: Weather Atlas[79] | |||||||||||||

jeremy likes boys

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1722 | 10,567 | — |

| 1765 | 15,520 | +46.9% |

| 1790 | 18,320 | +18.0% |

| 1800 | 24,937 | +36.1% |

| 1810 | 33,787 | +35.5% |

| 1820 | 43,298 | +28.1% |

| 1830 | 61,392 | +41.8% |

| 1840 | 93,383 | +52.1% |

| 1850 | 136,881 | +46.6% |

| 1860 | 177,840 | +29.9% |

| 1870 | 250,526 | +40.9% |

| 1880 | 362,839 | +44.8% |

| 1890 | 448,477 | +23.6% |

| 1900 | 560,892 | +25.1% |

| 1910 | 670,585 | +19.6% |

| 1920 | 748,060 | +11.6% |

| 1930 | 781,188 | +4.4% |

| 1940 | 770,816 | −1.3% |

| 1950 | 801,444 | +4.0% |

| 1960 | 697,197 | −13.0% |

| 1970 | 641,071 | −8.1% |

| 1980 | 562,994 | −12.2% |

| 1990 | 574,283 | +2.0% |

| 2000 | 589,141 | +2.6% |

| 2010 | 617,594 | +4.8% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90] | ||

According to the 2000 United States Census,Template:GR there were 589,141 people, 239,528 households, and 115,212 families residing in the city. When including the Greater Boston region, rather than just the city itself, the total is approximately 4.5 million. Boston's population density was 12,166 people per square mile (4,697/km2). There were 251,935 housing units at an average density of 5,203 per square mile (2,009/km2). The 2010 U.S. Census population count for the city was 617,594,[6] a 4.8% increase over 2000. During weekdays, the population of Boston can grow during the daytime to over 1.2 million, and can reach as many as 2 million during special events. This fluctuation of people is caused by hundreds of thousands of suburban residents who travel to the city for work, education, health care, and special events.[91]

In the city, the population was spread out with 19.8% under the age of 18, 16.2% from 18 to 24, 35.8% from 25 to 44, 17.8% from 45 to 64, and 10.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.2 males.[92] There were 239,528 households, of which 22.7% had children under the age of 18 living in them, 27.4% were married couples living together, 16.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 51.9% were non-families. 37.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 3.17.[92]

The median income for a household in the city was $39,629, and the median income for a family was $44,151. Males had a median income of $37,435 versus $32,421 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,353. 19.5% of the population and 15.3% of families are below the poverty line. Of the total population, 25.6% of those under the age of 18 and 18.2% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[93]

In 1950, whites represented 94.7% of Boston's population.[94] From the 1950s to the end of the 20th century, the proportion of non-Hispanic whites in the city declined; in 2000, non-Hispanic whites made up 49.5% of the city's population, making the city majority-minority for the first time. However, in recent years the city has experienced significant gentrification, in which affluent whites have moved into formerly non-white areas. Meanwhile, the city's black population has decreased. In 2006, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that non-Hispanic whites again formed a slight majority. But as of 2010, in part due to the housing crash, as well as increased efforts to make more affordable housing more available the minority population has rebounded. This may also have to do with an increased Latino population and more clarity surrounding U.S. Census statistics, which indicate a Non-Hispanic White population of 47 percent (some reports give slightly lower figures).[95][96][97]

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, the racial composition of Boston was as follows:[98]

- White: 53.9% (Non-Hispanic Whites: 47.0%)

- Black or African American: 22.4%

- Native American: 0.2%

- Asian: 8.9%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.0%

- Some other race: 1.6%

- Two or more races: 2.4%

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race): 17.5%

People of Irish descent form the largest single ethnic group in the city, making up 15.8% of the population, followed by Italians, accounting for 8.3% of the population. People of West Indian ancestry are another sizable group, at 6.4%,[99] about half of whom are of Haitian ancestry. Some neighborhoods, such as Dorchester, have received an influx of people of Vietnamese ancestry in recent decades. Neighborhoods such as Jamaica Plain and Roslindale have experienced a growing number of Dominican Americans. The city and greater area also has a large immigration population of South Asians, including the tenth-largest Indian community in the country, with an estimated 62,598 Indians.[100]

The city also has a sizable Jewish population with an estimated 25,000 Jews within the city and 227,000 within the Boston metro area; the number of congregations in Boston is estimated at 22.[101][102] The adjacent communities of Brookline and Newton are both approximately one-third Jewish.[101]

Accent

The "Boston accent" is widely parodied in the U.S. and the Kennedy family is often associated with it, though the Kennedys' speech is generally considered more an idiosyncratic mix of various accents such as Boston Brahman.[103][104][105] It is non-rhotic (i.e., drops the "r" sound at the end of syllables unless the next syllable starts with a vowel) and traditionally uses a "broad a" in certain words, so "bath" can sound like "bahth".[106] Boston English has many dialect words, such as "frappe", meaning "milkshake made with ice cream" (as opposed to other milkshakes).[107] The accent originated in the non-rhotic speech of 17th century East Anglia and Lincolnshire.[108]

Crime

The city has seen a great reduction in violent crime since the early 1990s. Boston's low crime rate over the past decade or so has been credited to the Boston Police Department's collaboration with neighborhood groups and church parishes to prevent youths from joining gangs, as well as involvement from the United States Attorney and District Attorney's offices. This helped lead in part to what has been touted as the "Boston Miracle". Murders in the city dropped from 152 in 1990 (for a murder rate of 26.5 per 100,000 people) to just 31—not one of them a juvenile—in 1999 (for a murder rate of 5.26 per 100,000).[109]

In the 2000s (decade), however, the annual murder count has fluctuated by as much as 50% compared with the year before, with 60 murders in 2002, followed by just 39 in 2003, 64 in 2004, and 75 in 2005. Although the figures are nowhere near the high-water mark set in 1990, the aberrations in the murder rate have been unsettling for many Bostonians and have prompted discussion over whether the Boston Police Department should reevaluate its approach to fighting crime.[109][110][111]

Economy

Encompassing $363 billion, the Greater Boston metropolitan area has the sixth-largest economy in the country and 12th-largest in the world.[113]

Boston's colleges and universities have a significant effect on the regional economy, with students contributing an estimated $4.8 billion annually to the city's economy.[114] Boston's schools are major employers and attract industries to the city and surrounding region. Boston is home to a number of technology companies and is a hub for biotechnology, with the Milken Institute rating Boston as the top life sciences cluster in the country.[115] Boston also receives the highest absolute amount of annual funding from the National Institutes of Health of all cities in the United States.[116]

Tourism comprises a large part of Boston's economy. In 2004, tourists spent $7.9 billion and made the city one of the ten-most-popular tourist locations in the country.[16] Because of Boston's status as a state capital and the regional home of federal agencies, law and government are another major component of the city's economy.[16] The city is also a major seaport along the United States' East Coast and is also the oldest continuously operated industrial and fishing port in the Western Hemisphere.[117]

Some of the other important industries are financial services, especially mutual funds and insurance.[16] Boston-based Fidelity Investments helped popularize the mutual fund in the 1980s and has made Boston one of the top financial cities in the United States. The city is home to the regional headquarters of Bank of America and Sovereign Bank, and it is a center for venture capital firms. State Street Corporation, which specializes in asset management and custody services, is based in the city. A 2008 study ranked Boston among the top 10 cities in the world for a career in finance.[118] Boston is a printing and publishing center — Houghton Mifflin is headquartered within the city, along with Bedford-St. Martin's Press, Beacon Press, and Little, Brown and Company. Pearson PLC publishing units also employ several hundred people in Boston. The city is home to three major convention centers—the Hynes Convention Center in the Back Bay, and the Seaport World Trade Center and Boston Convention and Exhibition Center on the South Boston waterfront.

Some of the major companies headquartered within the city are the Liberty Mutual insurance company, Gillette (now owned by Procter & Gamble), and New Balance. Boston is also home to management consulting firms The Boston Consulting Group and Bain & Company, as well as the private equity group Bain Capital.[119] Other major companies are located outside the city, especially along Route 128,[120] which serves as the center of the region's high-tech industry. In 2006, Boston and its metropolitan area ranked as the fourth-largest cybercity in the United States with 191,700 high-tech jobs. Only NYC Metro, DC Metro, and Silicon Valley have larger high-tech sectors.[121]

Boston is classified as an "incipient global city" by a 2004 study group at Loughborough University in England.[122] Classified as an Alpha-global city by GaWC studies, comparable to Vienna, Dublin, or Istanbul, Boston is placed among the top 30 cities in the world.[citation needed]

Culture

Boston shares many cultural roots with greater New England, including a dialect of the non-rhotic Eastern New England accent known as Boston English, and a regional cuisine with a large emphasis on seafood, salt, and dairy products. Irish Americans are a major influence on Boston's politics and religious institutions. Boston also has its own collection of neologisms known as Boston slang.[123]

The city has a number of ornate theatres, including the Cutler Majestic Theatre, Boston Opera House, Citi Performing Arts Center, the Colonial Theater, and the Orpheum Theatre. Renowned performing-arts organizations include the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Boston Ballet, Boston Early Music Festival, Boston Lyric Opera Company, OperaBoston, and the Handel and Haydn Society (one of the oldest choral companies in the United States).[125] The city is also a major center for contemporary classical music, with a number of performing groups, some of which are associated with the city's conservatories and universities. There are also many major annual events such as First Night, which occurs on New Year's Eve, the annual Boston Arts Festival at Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park, Italian summer feasts in the North End honoring Catholic saints, and several events during the Fourth of July period. These events include the week-long Harborfest festivities[126] and a Boston Pops concert accompanied by fireworks on the banks of the Charles River.[127]

Because of the city's prominent role in the American Revolution, several historic sites relating to that period are preserved as part of the Boston National Historical Park. Many are found along the Freedom Trail, which is marked by a red line of bricks embedded in the ground. The city is also home to several prominent art museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. In December 2006, the Institute of Contemporary Art moved from its Back Bay location to a new contemporary building designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro located in the Seaport District. The University of Massachusetts campus at Columbia Point houses the John F. Kennedy Library. The Boston Athenaeum (one of the oldest independent libraries in the United States),[128] Boston Children's Museum, Bull & Finch Pub (whose building is known from the television show Cheers), Museum of Science, and the New England Aquarium are within the city.

Boston is also one of the birthplaces of the hardcore punk genre of music. Boston musicians have contributed significantly to this music scene over the years (see also Boston hardcore). Boston neighborhoods were home to one of the leading local third wave ska and ska punk scenes in the 1990s, led by bands such as The Mighty Mighty Bosstones and The Allstonians. The 1980s' hardcore punk-rock compilation This Is Boston, Not L.A. highlights some of the bands that built the genre. Several nightclubs, such as The Channel, Bunnratty's in Allston, and The Rathskeller, were renowned for showcasing both local punk-rock bands and those from farther afield. All of these clubs are now closed. Many were razed or converted during recent gentrification.[129]

Boston has been a noted religious center from its earliest days. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston serves nearly 300 parishes and is based in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross (1875) in the South End, while the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, with the Cathedral Church of St. Paul (1819) as its episcopal seat, serves just under 200 congregations. Two Protestant faiths are headquartered in Boston: Unitarian Universalism, with its headquarters on Beacon Hill, and the Christian Scientists, headquartered in Back Bay at the Mother Church (1894). The oldest church in Boston is King's Chapel, the city's first Anglican church, founded in 1686 and converted to Unitarianism in 1785. Other notable churches include Christ Church (better known as Old North Church, 1723), the oldest church building in the city, Trinity Church (1733), Park Street Church (1809), First Church in Boston (congregation founded 1630, building raised 1868), Old South Church (1874), and Basilica and Shrine of Our Lady of Perpetual Help on Mission Hill (1878).

Media

The Boston Globe (owned by The New York Times Company) and the Boston Herald are two of Boston's major daily newspapers. The city is also served by other publications such as The Boston Phoenix, Boston magazine, The Improper Bostonian, Boston's Weekly Dig, and the Boston edition of Metro. The Christian Science Monitor, headquartered in Boston, was formerly a worldwide daily newspaper but ended publication of daily print editions in 2009, switching to continuous online and weekly magazine format publications.[130] The Boston Globe also releases a teen publication to the city's public high schools. The newspaper Teens in Print or T.i.P. is written by the city's teens and delivered quarterly within the school year.[131]

The city's growing Latino population has given rise to a number of local and regional Spanish-language newspapers. These include El Planeta (owned by The Boston Phoenix), El Mundo, and La Semana. Siglo21, with its main offices in nearby Lawrence, is also widely distributed.

Boston has the largest broadcasting market in New England, with the Boston radio market being the eleventh largest in the United States.[132] Several major AM stations include talk radio WRKO 680 AM, sports/talk station WEEI 850 AM, and news radio WBZ 1030 AM. A variety of FM radio formats serve the area, as do NPR stations WBUR and WGBH. College and university radio stations include WERS (Emerson), WHRB (Harvard), WUMB (UMass Boston), WMBR (M.I.T.), WZBC (Boston College), WMFO (Tufts University), WBRS (Brandeis University), WTBU (Boston University, campus and web only), WRBB (Northeastern University) and WMLN (Curry College).

The Boston television DMA, which also includes Manchester, New Hampshire, is the seventh largest in the United States.[133] The city is served by stations representing every major American network, including WBZ 4 and its sister station WSBK 38 (the former with CBS, the latter an independent, nonaffiliated station), WCVB 5 (ABC), WHDH 7 (NBC), WFXT 25 (Fox), WUNI 27 (Univision), WBIN 50 (MyNetworkTV), and WLVI 56 (The CW). Boston is also home to PBS station WGBH 2, a major producer of PBS programs, which also operates WGBX 44. Most Boston television stations have their transmitters in nearby Needham and Newton along the Route 128 corridor.[134]

Sports

Boston has teams in the four major North American professional sports leagues, and has won 33 championships in these leagues, as of 2011.[135]

The Boston Red Sox, a founding member of the American League of Major League Baseball in 1901, play their home games at Fenway Park, near Kenmore Square in the Fenway section of Boston. Built in 1912, it is the oldest sports arena or stadium in active use in the United States among the four major professional American sports leagues, encompassing Major League Baseball, the National Football League, National Basketball Association, and the National Hockey League.[136] Boston was also the site of the first game of the first modern World Series, in 1903. The series was played between the AL Champion Boston Americans and the NL champion Pittsburgh Pirates.[137][138] Persistent reports that the team was known in 1903 as the "Boston Pilgrims" appear to be unfounded.[139] Boston's first professional baseball team was the Red Stockings, one of the charter members of the National Association in 1871, and of the National League in 1876. The team played under that name until 1883, under the name Beaneaters until 1911, and under the name Braves from 1912 until they moved to Milwaukee after the 1952 season. Since 1966 they have played in Atlanta as the Atlanta Braves.[140]

The TD Garden (formerly called the FleetCenter) is adjoined to North Station and is the home of three major league teams: the Boston Blazers of the National Lacrosse League, the 2011 Stanley Cup champion Boston Bruins of the National Hockey League; and the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association. The arena seats 18,624 for basketball games and 17,565 for ice hockey games. The Bruins were the first American member of the National Hockey League and an Original Six franchise.[141] The Boston Celtics were founding members of the Basketball Association of America, one of the two leagues that merged to form the NBA.[142] The Celtics have the distinction of having won more championships than any other NBA team, with seventeen.[143]

While they have played in suburban Foxborough since 1971, the New England Patriots were founded in 1960 as the Boston Patriots, changing their name in 1971 to better reflect its status as New England's team. A charter member of the American Football League, the team joined the National Football League in 1970. The team has won the Super Bowl three times, in 2001, 2003, and 2004.[144] They share Gillette Stadium with the New England Revolution of Major League Soccer. The Boston Breakers of Women's Professional Soccer, which formed in 2009, play their home games at Harvard Stadium in Allston.[145]

Boston's many colleges and universities are active in college athletics. Four NCAA Division I members play their games in the city—Boston College (Atlantic Coast Conference), Boston University (America East Conference), Harvard University (Ivy League), and Northeastern University (Colonial Athletic Association). Of the four, only Boston College participates in college football at the highest level, the Football Bowl Subdivision. Harvard participates in the second-highest level, the Football Championship Subdivision. Boston University and Northeastern University do not have football teams. All but Harvard belong to the Hockey East conference; Harvard belongs to the ECAC in hockey. The hockey teams of these four universities meet every year in a four-team tournament known as the "Beanpot Tournament", which is played at the TD Garden over two Monday nights in February.[146]

One of the best known sporting events in the city is the Boston Marathon, the 42.195-kilometre (26.219 mi) run from Hopkinton to Copley Square in the Back Bay which is the world's oldest annual marathon run.[147] It is run on Patriots' Day in April and always coincides with a Red Sox home baseball game that starts at 11:05 am, the only MLB game all year to start before noon local time.[148] Another major event held annually in the city is the Head of the Charles Regatta rowing competition on the Charles River.[149]

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Bruins | NHL | Hockey | TD Garden | 1924 | 6 Stanley Cups |

| Boston Celtics | NBA | Basketball | TD Garden | 1946 | 17 NBA Titles |

| Boston Red Sox | MLB | Baseball | Fenway Park | 1901 | 7 World Series Titles 12 AL Pennants |

| New England Patriots | NFL | Football | Gillette Stadium | 1960 | 3 Super Bowl Titles 7 AFC Championships |

| New England Revolution | MLS | Soccer | Gillette Stadium | 1995 | 1 U.S. Open Cup 1 Superliga |

| Boston Blazers | NLL | Lacrosse (Indoor) | TD Garden | 2008 | None |

| Boston Breakers | WPS | Soccer | Harvard Stadium | 2001 | None |

| Boston Cannons | MLL | Lacrosse (Outdoor) | Harvard Stadium | 2001 | 1 Steinfeld Cup |

| Boston Aztec | WPSL | Soccer | Amesbury Sports Park | 2005 | 1 WPSL Title |

| Boston Demons | USAFL | Australian Rules Football | Ipswich River Park | 1997 | 2 National Championships |

| Boston Militia | WFA | Football | Dilboy Stadium | 2008 | 2 Championships |

| New England Riptide | NPF | Softball | Martin Softball Field | 2004 | 1 Cowles Cup |

Government

Boston has a strong mayor – council government system in which the mayor is vested with extensive executive powers. The mayor is elected to a four-year term by plurality voting. The current mayor of Boston is Thomas Menino. He was elected in 1993 and was reelected in 2009 for a fifth term, the longest in Boston history. Boston City Council is elected every two years. There are nine district seats, each elected by the residents of that district through plurality voting, and four at-large seats. Each voter casts up to four votes for at-large councilors, with no more than one vote per candidate. The candidates with the four highest vote totals are elected. The president of the city council is elected by the councilors from within themselves. The school committee for the Boston Public Schools is appointed by the mayor.[150] The Boston Redevelopment Authority and the Zoning Board of Appeals (a seven-person body appointed by the mayor) share responsibility for land-use planning.[151]

In addition to city government, numerous commissions and state authorities—including the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, the Boston Public Health Commission, and the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport)—play a role in the life of Bostonians. As the capital of Massachusetts, Boston plays a major role in state politics. The city has several properties relating to the United States federal government, including the John F. Kennedy Federal Office Building and the Thomas P. O'Neill Federal Building.[152] Boston also serves as the home of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit and of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts; Boston is the headquarters of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (the First District of the Federal Reserve).

Federally, Boston is part of Massachusetts's 8th and 9th congressional districts,[153] represented respectively by Mike Capuano, elected in 1998, and Stephen Lynch, elected in 2001; both are Democrats. The state's senior member of the United States Senate is Democrat John Kerry, elected in 1984. The state's junior member of the United States Senate is Republican Scott Brown was elected in 2010 to fill the vacancy caused by the death of long-time Democratic senator Ted Kennedy.

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of October 15, 2008[154] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | Democratic | 209,710 | 55.04% | Republican | 27,541 | 7.23% | Unaffiliated | 140,601 | 36.90% | Minor Parties | 3,161 | 0.83% | |

| Total | 381,013 | 100% | |||||||||||||

Education

Boston's reputation as a higher education center derives in large part from the teaching and research activities of more than 100 colleges and universities located in the Greater Boston Area, with more than 250,000 students attending college in Boston and Cambridge alone.[155] Within the city, Boston University exudes a large presence as the city's fourth-largest employer,[156] and maintains a campus along the Charles River on Commonwealth Avenue and its medical campus in the South End. Northeastern University, another large private university, is located in the Fenway area, and is particularly known for its Engineering, Business and Health Science schools and cooperative education program. Suffolk University, the third largest university in Boston, is located in the Beacon Hill area, and is known for its law school and business school.[157][158] Boston College, a private Catholic Jesuit university, whose original campus was located in the South End, now straddles the Boston (Brighton)-Newton border, with planned expansions further into Brighton.[159] Boston's only public university is the University of Massachusetts Boston, located on Columbia Point in Dorchester. Roxbury Community College and Bunker Hill Community College are the city's two public community colleges.

Boston has several smaller private colleges and universities. Emmanuel College, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Simmons College, Wheelock College, and Wentworth Institute of Technology are founding members of the Colleges of the Fenway and are located adjacent to Northeastern University. New England School of Law, a small private law school located in the theater district, was originally established as America's first all female law school.[160] Emerson College, a small private college with a strong reputation in the fields of performing arts, journalism, writing, and film, is located near Boston Common.

Boston is also home to several conservatories and art schools, including The Art Institute of Boston (Lesley University), Massachusetts College of Art, New England Institute of Art, New England School of Art and Design (Suffolk University), and the New England Conservatory (the oldest independent conservatory in the United States).[161] Other conservatories include the Boston Conservatory, the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Berklee College of Music.

Several universities located outside Boston have a major presence in the city. Harvard University, the nation's oldest, is located across the Charles River in Cambridge. Its business and medical schools are in Boston, and there are plans for additional expansion into Boston's Allston neighborhood.[162] The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which originated in Boston and was long known as "Boston Tech", moved across the river to Cambridge in 1916. Tufts University administers its medical and dental school adjacent to the Tufts Medical Center, a 451-bed academic medical institution that is home to both a full-service hospital for adults and the Floating Hospital for Children. Tufts' main campus, including the renowned Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, is located just north of the city in Somerville and Medford.

Boston Public Schools, the oldest public school system in the U.S., enrolls 57,000 students from pre-kindergarten to grade 12.[17] The system operates 145 schools, which includes Boston Latin School (the oldest public school in the United States, established in 1635) which, along with Boston Latin Academy and John D. O'Bryant School of Math & Science, are highly prestigious public exam schools admitting students in the 7th and 9th grades only and serving grades 7–12), English High (the oldest public high school, established 1821), and the Mather School (the oldest public elementary school, established in 1639).[17] In 2002, Forbes Magazine ranked the Boston Public Schools as the best large city school system in the country, with a graduation rate of 82%.[163] In 2005, the student population within the school system was 45.5% Black or African American, 31.2% Hispanic or Latino, 14% White, and 9% Asian, as compared with 24%, 14%, 49%, and 8% respectively for the city as a whole.[164][165] The city also has private, parochial, and charter schools and approximately 3000 students of racial minorities attend participating suburban schools through the Metropolitan Educational Opportunity Council, or METCO.

Healthcare

The Longwood Medical and Academic Area is a region of Boston with a concentration of medical and research facilities, including Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Children's Hospital Boston, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Harvard School of Public Health, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, and Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.[166] Massachusetts General Hospital is near the Beacon Hill neighborhood, with the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital nearby. St. Elizabeth's Medical Center is in Brighton Center of Boston's Brighton neighborhood. New England Baptist Hospital is in Mission Hill. Boston has Veterans Affairs medical centers in the Jamaica Plain and West Roxbury neighborhoods.[167] The Boston Public Health Commission, an agency of the Massachusetts government, oversees health concerns for Boston residents.[168]

Many of Boston's medical facilities are associated with universities. The facilities in the Longwood Medical and Academic Area and in Massachusetts General Hospital are well-known research medical centers affiliated with Harvard Medical School.[169] Tufts Medical Center (formerly Tufts-New England Medical Center), located in the southern portion of the Chinatown neighborhood, is affiliated with Tufts University School of Medicine. Boston Medical Center, located in the South End neighborhood, is the primary teaching facility for the Boston University School of Medicine as well as the largest trauma center in the Boston area;[170] it was formed by the merger of Boston University Hospital and Boston City Hospital, which was the first municipal hospital in the United States.[171]

Utilities

Water supply and sewage-disposal services are provided by the Boston Water and Sewer Commission.[172] The Commission in turn purchases wholesale water and sewage disposal from the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. The city's water comes from the Quabbin Reservoir and the Wachusett Reservoir, which are about 65 miles (105 km) and 35 miles (56 km) west of the city respectively.[173] Boston's tap water has been ranked among the best in the country,[174] and Boston is one of five cities in the country with tap water pure enough to be exempt from Environmental Protection Agency filtration requirements.[175] NSTAR is the exclusive electricity distributor to the city, though due to deregulation, customers now have a choice of electric generation companies. Natural gas is distributed by National Grid plc (originally KeySpan, the successor company to Boston Gas); only commercial and industrial customers may choose an alternate natural gas supplier.[176] Municipal steam services are provided by Veolia Energy North America and its subsidiary Trigen Energy Corporation;[177][178] which comprise the original assets of the defunct Boston Heating Company.[179][180]

Verizon, successor to New England Telephone, NYNEX, Bell Atlantic, and earlier, the Bell System, is the primary wired telephone service provider for the area. Phone service is also available from various national wireless companies. Cable television is available from Comcast and RCN, with broadband Internet access provided by the same companies in certain areas. A variety of DSL providers and resellers are able to provide broadband Internet over Verizon-owned phone lines.[181] Galaxy Internet Services (GIS) has also moved to the forefront to deploy municipal Wi-Fi broadband Internet throughout areas of the city of Boston.[182]

Transportation

Logan International Airport, located in the East Boston neighborhood, handles most of the scheduled passenger service for Boston.[183] Surrounding the city are three major general aviation relievers: Beverly Municipal Airport to the north, Hanscom Field in Bedford, to the west, and Norwood Memorial Airport to the south. T. F. Green Airport serving Providence, Rhode Island, Bradley International Airport outside of Hartford, Connecticut, and Manchester-Boston Airport in Manchester, New Hampshire, also provide scheduled passenger service to the Boston area.

Downtown Boston's streets were not organized on a grid, but grew in a meandering organic pattern from early in the 17th century. They were created as needed, and as wharves and landfill expanded the area of the small Boston peninsula.[184] Along with several rotaries, roads change names and lose and add lanes seemingly at random. By contrast, streets in the Back Bay, East Boston, the South End, and South Boston do follow a grid system.

Boston is the eastern terminus of cross-continent I-90, which in Massachusetts runs along the Massachusetts Turnpike. Originally known as the Circumferential Highway, Route 128 carries I-95 over a portion of its route west and north of the city. U.S. 1 and I-93 run concurrently north to south through the city from Charlestown to Dorchester, joined by Massachusetts Route 3 after the Zakim Bridge over the Charles River. The elevated portion of the Central Artery, which carried these routes through downtown Boston, was replaced with the O'Neill Tunnel during the Big Dig, substantially completed in early 2006.

With nearly a third of Bostonians using public transit for their commute to work, Boston has the fourth-highest rate of public transit usage in the country.[185] The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) operates what was the first underground rapid transit system in the United States and is now the fourth busiest rapid transit system in the country,[18] having been expanded to 65.5 miles (105 km) of track,[186] reaching as far north as Malden, as far south as Braintree, and as far west as Newton—collectively known as the "T". The MBTA also operates the nation's seventh busiest bus network, as well as water shuttles, and the nation's busiest commuter rail network outside of New York City or Chicago, totaling over 200 miles (320 km),[186] extending north to the Merrimack Valley, west to Worcester, and south to Providence.

Amtrak's Northeast Corridor and Chicago lines originate at South Station and stop at Back Bay. Fast Northeast Corridor trains, which serve New York City, Washington, D.C., and points in between, also stop at Route 128 Station in the southwestern suburbs of Boston.[187] Meanwhile, Amtrak's Downeaster service to Maine originates at North Station.[188]

Nicknamed "The Walking City," Boston hosts more pedestrian commuters than do other comparably populated cities. Owing to factors such as the compactness of the city and large student population, 13% of the population commutes by foot, making it the highest percentage of pedestrian commuters in the country out of the major American cities.[189] In 2011, Walk Score ranked Boston the third most walkable city in the United States.[190][191]

Between 1999 and 2006, Bicycling magazine named Boston as one of the worst cities in the U.S. for cycling three times;[192] regardless, it has one of the highest rates of bicycle commuting.[193] In September 2007, Mayor Menino started a bicycle program called Boston Bikes with a goal of improving bicycling conditions by adding bike lanes, racks, and offering bikeshare programs. In 2008, as a consequence the same magazine put Boston on its list of its "Five for the Future" list as a "Future Best City" for biking,[194][195] and Boston's bicycle commuting percentage increased from 1% in 2000 to 2.1% in 2009.[196] The bikeshare program, called Hubway, launched in late July 2011.[197] In tandem with the program, police announced intention to step up enforcement of traffic laws, both on drivers and bikers,[198] as part of an effort to improve safety and ameliorate the city's growing clash between bikers and motorists.[199][200][201]

Sister cities

Boston has eight official sister cities as recognized by Sister Cities International.[202] The date column indicates the year in which the relationship was established. Kyoto was Boston's first sister city.

| City | Country | Date | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kyoto | 1959 | [203] | |

| Strasbourg | 1960 | [204][205] | |

| Barcelona | 1980 | [206][207] | |

| Hangzhou | 1982 | [202] | |

| Padua | 1983 | [208] | |

| Melbourne | 1985 | ||

| Taipei | 1996 | [210] | |

| Sekondi-Takoradi | 2001 | [202] |

Boston also has less formal friendship or partnership relationships with an additional three cities.

| City | Country | Date | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boston | 1999 | [211][212] | |

| Haifa | 1999 | [213] | |

| Valladolid | 2007 | [214] |

See also

- Boston in fiction

- Boston nicknames

- List of diplomatic missions in Boston

- List of fictional people from Boston

- List of people from Boston

- List of songs about Boston

- List of tallest buildings in Boston

- List of television shows set in Boston

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Boston, Massachusetts

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Dalager, Norman (August 10, 2006). "What's in a nickname?". Boston Globe. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "Boston Travel & Vacations". Britannia.com. 2006. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau, Census 2000 Summary File 1. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|ST-7S&-_lang=ignored (help) - ^ "United States by Urbanized Area; and for Puerto Rico". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau, Census 2000 Summary File 1. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|US-12S&-_lang=ignored (help) - ^ "United States by County by State, and for Puerto Rico". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau, Census 2000 Summary File 1. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|US-25S&-_lang=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Population and Housing Occupancy Status: 2010 – State – County Subdivision, 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ "Alphabetically sorted list of Census 2000 Urbanized Areas" (TXT). United States Census Bureau, Geography Division. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ a b "Metropolitan and micropolitan statistical area population and estimated components of change: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2008 (CBSA-EST2008-alldata)". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. Archived from the original (CSV) on March 22, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ a b "Combined statistical area population and estimated components of change: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2008 (CSA-EST2008-alldata)" (CSV). United States Census Bureau, Population Division. Retrieved April 11, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "ZIP Code Lookup – Search By City". United States Postal Service. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "massachusetts". infoplease. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- ^ Steinbicker, Earl (2000). 50 one day adventures—Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire. Hastings House/Daytrips Publishers. p. 7. ISBN 0-8038-2008-9.

- ^ "Boston Worcester Manchester Demographic Profile: Region 19". Federal Transit Administration. January 31, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2010. 21 pp.

- ^ "Boston-Worcester-Manchester, MA-RI-NH Combined Statistical Area" (PDF). U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2007. Retrieved June 20, 2009. Included in the CSA: MA counties: Bristol, Essex, Middlesex, Norfolk, Plymouth, Suffolk and Worcester; NH counties: Belknap, Hillsborough, Merrimack, Rockingham and Strafford; RI counties (entire state): Bristol, Kent, Newport, Providence and Washington (South County)

- ^ a b c d e Banner, David. "Boston History – The History of Boston, Massachusetts". SearchBoston. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Boston Tourism". Thomson Gale (Thomson Corporation). 2006. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "BPS at a Glance". Boston Public Schools. March 14, 2007. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^ a b Fagundes, David (April 28, 2003). The Rough Guide to Boston. Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-044-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Banner, David. "Going to College in Boston". SearchBoston. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ^ "Boston City Guide". World Travel Guide. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ [1] Z/Yen Group'.' Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ "The top 100 cities of the global innovation economy". 2THINKNOW. September 1, 2010.

- ^ "Boston: The City of Innovation". TalentCulture. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ Kirsner, Scott (July 20, 2010). "Boston is #1...But will we hold on to the top spot? – Innovation Economy". Boston Globe. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Heudorfer, Bonnie; Bluestone, Barry (2004). "The Greater Boston Housing Report Card" (PDF). Center for Urban and Regional Policy (CURP), Northeastern University. p. 6. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Quality of Living global city rankings 2010 – Mercer survey". Mercer. May 26, 2010. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ "Archaeology of the Central Artery Project: Highway to the Past". Commonwealth Museum – Massachusetts Historical Commission. 2007. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

- ^ ""Growth" to Boston in its Heyday, 1640s to 1730s" (PDF). Boston History & Innovation Collaborative. 2006. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ "Colonial Boston". University Archives. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ a b "Boston, Massachusetts". U-S-History.com. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "Boston African American National Historic Site". National Park Service. April 28, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ "Fugitive Slave Law". The Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "The "Trial" of Anthony Burns". The Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "150th Anniversary of Anthony Burns Fugitive Slave Case". Suffolk University. April 24, 2004. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "About Boston". City of Boston. 2006. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ a b State Street Trust Company; Walton Advertising and Printing Company (1922). Boston: one hundred years a city (TXT). Vol. 2. Boston: State Street Trust Company. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "People & Events: Boston's Immigrant Population". WGBH/PBS Online (American Experience). 2003. Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- ^ "Immigration Records". The National Archives. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ "Boston People". city-data.com. 2007. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- ^ "The History of Land Fill in Boston". iBoston.org. 2006. Retrieved January 9, 2006.. Also see Howe, Jeffery (1996). "Boston: History of the Landfills". Boston College. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ Historical Atlas of Massachusetts. University of Massachusetts. 1991. p. 37.

- ^ Holleran, Michael (2001). "Problems with Change". Boston's Changeful Times: Origins of Preservation and Planning in America. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. Pg. 41. ISBN 0-8018-6644-8. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

{{cite book}}:|page=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|separator=,|laysummary=, and|lastauthoramp=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff writer (March 26, 1892, Wednesday). "BOSTON'S ANNEXATION SCHEMES.; PROPOSAL TO ABSORB CAMBRIDGE AND OTHER NEAR-BY TOWNS". The New York Times. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 27, 1892. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|pmd=(help) - ^ Rezendes, Michael (October 13, 1991). "Has the time for Chelsea's annexation to Boston come? The Hub hasn't grown since 1912, and something has to follow that beleaguered community's receivership". The Boston Globe. p. 80. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|pmd=(help) - ^ Estes, Andrea (September 9, 1991). "Flynn offers to annex Chelsea". Boston Herald. p. 1. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|pmd=(help); More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Park, Edwards (November 24, 2004). "Eric Postpischil's Molasses Disaster Pages, Smithsonian Article". Eric Postpischil's Domain. 14 (8). Smithsonian Institution: 213–230. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ^ Collins, Monica (August 7, 2005). "Born Again". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ Roessner, Jane. "A Decent Place to Live: from Columbia Point to Harbor Point – A Community History", Boston: Northeastern University Press, c2000. Cf. p. 80, "The Columbia Point Health Center: The First Community Health Center in the Country".

- ^ Cf. Roessner, p.293. "The HOPE VI housing program, inspired in part by the success of Harbor Point, was created by legislation passed by Congress in 1992."

- ^ Puleo, Stephen (2007). "Epilogue: Today". The Boston Italians (illustrated ed.). Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5036-1. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^

Feeney, Mark; Mehegan, David (April 15, 2005). "Atlantic, 148-year institution, leaving city". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hampson, Rick (April 19, 2005). "Studies: Gentrification a boost for everyone". USA Today. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "Cost of Living Index for Selected U.S. Cities, 2005". Information Please Database. Pearson Education. 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "Cost of living – The world's most expensive big cities". City Mayors. July 28, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ "2011 Quality of Living worldwide city rankings – Mercer survey". November 29, 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ After New York City and San Francisco. Many cities, such as Paterson, New Jersey, are denser but are part of a larger city's metropolitan area.

- ^ http://www.massbike.org/bikeways/neponset/

- ^ "Kings Chapel Burying Ground, USGS Boston South (MA) Topo Map". TopoZone. 2006. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ "Elevation data – Boston". U.S. Geological Survey. 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ^ "Bellevue Hill, Massachusetts". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- ^ "Boston Skyscrapers". Emporis.com. 2005. Retrieved May 15, 2005.

- ^ "About the SEHS". South End Historical Society. 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ^ "Prudential Skywalk Observatory". CelebrateBoston.com. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "Boston Common". CelebrateBoston.com. 2006. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ^ "Franklin Park". City of Boston. 2007. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^ Official Boston neighborhoods, defined here [2].

- ^ NCDC maximum temperature days chart

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Boston Extremeswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Weather". City of Boston Film Bureau. 2007. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ "Massachusetts – Climate". city-data.com (Thomson Gale). 2005. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ "May in the Northeast". Intellicast.com. 2003. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ Wangsness, Lisa (October 30, 2005). "Snowstorm packs October surprise". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ Ryan, Andrew (July 11, 2007). "Sea breeze keeps Boston 25 degrees cooler while others swelter". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ Ryan, Andrew (June 9, 2008). "Boston sea breeze drops temperature 20 degrees in 20 minutes". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ ThreadEx

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for BOSTON/LOGAN INT'L AIRPORT, MA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Boston, Massachusetts, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.