Champagne

Champagne (/ʃæmˈpeɪn/; French: [ʃɑ̃paɲ] ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation,[1] which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, specific grape-pressing methods and secondary fermentation of the wine in the bottle to cause carbonation.[2]

The grapes Pinot noir, Pinot meunier, and Chardonnay are used to produce almost all Champagne, but small amounts of Pinot blanc, Pinot gris (called Fromenteau in Champagne), Arbane, and Petit Meslier are vinified as well.

Champagne became associated with royalty in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. The leading manufacturers made efforts to associate their Champagnes with nobility and royalty through advertising and packaging, which led to its popularity among the emerging middle class.[1]

Origins

[edit]

Still wines from the Champagne region were known before medieval times. The Romans were the first to plant vineyards in this area of northeast France, with the region being tentatively cultivated by the 5th century. Cultivation was initially slow due to the unpopular edict by Emperor Domitian that all colonial vines must be uprooted. When Emperor Probus, the son of a gardener, rescinded the edict, a temple to Bacchus was erected, and the region started to produce a light, fruity, red wine that contrasted with heavier Italian brews often fortified with resin and herbs.[3] Later, church owned vineyards, and monks produced wine for use in the sacrament of the Eucharist. French kings were traditionally anointed in Reims, and champagne was served as part of coronation festivities. The Champenois were envious of the reputation of the wines made by their Burgundian neighbours to the south and sought to produce wines of equal acclaim. However, the northern climate of the region gave the Champenois a unique set of challenges in making red wine. At the far extremes of sustainable viticulture, the grapes would struggle to ripen fully and often would have bracing levels of acidity and low sugar levels. The wines would be lighter bodied and thinner than the Burgundy wines they sought to outdo.[4]

Contrary to legend and popular assumption, Dom Pérignon did not invent sparkling wine, though he did make important contributions to the production and quality of both still and sparkling Champagne wines.[5][6] The oldest recorded sparkling wine is Blanquette de Limoux, which was invented by Benedictine monks in the Abbey of Saint-Hilaire, near Carcassonne, in 1531.[7] They achieved this by bottling the wine before the initial fermentation had ended. Over a century later, the English scientist and physician Christopher Merret documented the addition of sugar to a finished wine to create a second fermentation six years before Dom Pérignon set foot in the Abbey of Hautvillers. Merret presented a paper at the Royal Society, in which he detailed what is now called méthode traditionnelle, in 1662.[8] Merret's discoveries coincided also with English glass-makers' technical developments that allowed bottles to be produced that could withstand the required internal pressures during secondary fermentation. French glass-makers at this time could not produce bottles of the required quality or strength[citation needed]. As early as 1663, the poet Samuel Butler referred to "brisk champagne".[9]

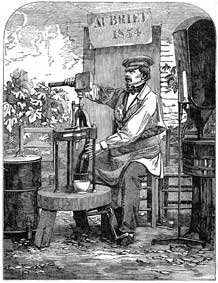

In France, the first sparkling champagne was created accidentally; the pressure in the bottle led it to be called "the devil's wine" (le vin du diable), as bottles exploded or corks popped. At the time, bubbles were considered a fault. In 1844, Adolphe Jaquesson invented the muselet to prevent the corks from blowing out. Initial versions were difficult to apply and inconvenient to remove.[10][11] Even when it was deliberately produced as a sparkling wine, champagne was for a very long time made by the méthode rurale, where the wine was bottled before the initial fermentation had finished. Champagne did not use the méthode champenoise until the 19th century, about 200 years after Merret documented the process. The 19th century saw a dramatic growth in champagne production, going from a regional production of 300,000 bottles a year in 1800 to 20 million bottles in 1850.[12] In 2007, champagne sales hit a record of 338.7 million bottles.[13]

In the 19th century, champagne was noticeably sweeter than today's champagnes. The trend towards drier champagne began when Perrier-Jouët decided not to sweeten his 1846 vintage before exporting it to London. The designation Brut Champagne was created for the British in 1876.[14]

The only wines that are legally allowed to be named “Champagne” must be bottled within 100 miles of the Champagne region in France. The name is legally protected by European law and an 1891 treaty that requires true champagne to be produced in the Champagne region and made from the Pinot Meunier, Pinot Noir, or Chardonnay grapes grown in this region.

Rights to the name

[edit]

The Champagne winemaking community, under the auspices of the Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne (CIVC), has developed a comprehensive set of rules and regulations for all wine produced in the region to protect its economic interests. They include codification of the most suitable growing places, the most suitable grape types (most Champagne is a blend of up to three grape varieties, though other varieties are allowed), and a lengthy set of requirements specifying most aspects of viticulture. This includes pruning, vineyard yield, the degree of pressing, and the time that wine must remain on its lees before bottling. It can also limit the release of Champagne to market to maintain prices. Only when a wine meets these requirements may it be labelled Champagne. The rules agreed upon by the CIVC are submitted for the final approval of the Institut national de l'origine et de la qualité (formerly the Institut National des Appellations d'Origine, INAO).

In 2007, the INAO, the government organization that controls wine appellations in France, was preparing to make the largest revision of the region's legal boundaries since 1927 in response to economic pressures. With soaring demand and limited production of grapes, Champagne houses say the rising price could produce a consumer backlash that would harm the industry for years into the future. That and political pressure from villages that wanted to be included in the expanded boundaries led to the move. Changes are subject to significant scientific review and are said not to impact Champagne-produced grapes until 2020.[15] A final decision is not expected until 2023[16] or 2024.[17]

Use of the word Champagne

[edit]

Sparkling wines are produced worldwide, but many legal structures reserve the word Champagne exclusively for sparkling wines from the Champagne region, made in accordance with Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne regulations. In the European Union and many other countries, the name Champagne is legally protected by the Madrid system under an 1891 treaty, which reserved it for the sparkling wine produced in the eponymous region and adhering to the standards defined for it as an appellation d'origine contrôlée; the protection was reaffirmed in the Treaty of Versailles after World War I. Over 70 countries have adopted similar legal protection. Most recently Australia,[18] Chile, Brazil, Canada and China passed laws or signed agreements with Europe that limit the use of the term "Champagne" to only those products produced in the Champagne region. The United States bans the use of all new U.S.-produced wine brands.[19] However, those that had approval to use the term on labels before 2006 may continue to use it, provided the term is accompanied by the wine's actual origin (e.g., "California").[19] The majority of US-produced sparkling wines do not use the term Champagne on their labels,[20] and some states, such as Oregon,[21] ban producers in their states from using the term.

Several key U.S. wine regions, such as those in California (Napa, Sonoma Valley, Paso Robles), Oregon, and Walla Walla, Washington, came to consider the remaining semi-generic labels as harmful to their reputations (cf. Napa Declaration on Place).

Even the terms méthode champenoise and Champagne method were forbidden by an EU court decision in 1994.[22] As of 2005[update] the description most often used for sparkling wines using the second fermentation in the bottle process, but not from the Champagne region, is méthode traditionnelle. Sparkling wines are produced worldwide, and many producers use special terms to define them: Spain uses Cava, Italy designates it spumante, and South Africa uses cap classique. An Italian sparkling wine made from the Muscat grape uses the DOCG Asti and from the Glera grape the DOC Prosecco. In Germany, Sekt is a common sparkling wine. Other French wine regions cannot use the name Champagne: e.g., Burgundy and Alsace produce Crémant. In 2008, more than 3,000 bottles of sparkling wine produced in California labelled with the term "Champagne" were destroyed by Belgian government authorities.[23]

Regardless of the legal requirements for labeling, extensive education efforts by the Champagne region, and the use of alternative names by non-Champagne sparkling wine producers, some consumers, and wine sellers, including "Korbels California Champagne", use Champagne as a generic term for white sparkling wines, regardless of origin.

The village of Champagne, Switzerland has traditionally made a still wine labelled as "Champagne": the earliest records of viticulture dated to 1657. In 1999, in an accord with the EU, the Swiss government conceded that, by 2004, the village would phase out the use of the name. Sales dropped from 110,000 bottles a year to 32,000 after the change. In April 2008, the villagers resolved to fight against the restriction following a Swiss open-air vote.[24]

In the Soviet Union, all sparkling wines were called шампанское (shampanskoe, Russian for "that, which is of Champagne"). The name is still used today for some brands of sparkling wines produced in former Soviet republics, such as Sovetskoye Shampanskoye and Rossiyskoe Shampanskoe. In 2021, Russia banned the use of the designation шампанское for imported sparkling wine, including sparkling wine produced in the Champagne wine region, reserving the designation for domestically produced sparkling wine only.[25][26]

Production

[edit]

Formerly known as méthode champenoise or méthode classique, champagne is produced by a traditional method. After primary fermentation and bottling, a second alcoholic fermentation occurs in the bottle. This second fermentation is induced by adding several grams of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and rock sugar to the bottle – although each brand has its own secret recipe.[27] According to the appellation d'origine contrôlée a minimum of one and a half years is required to completely develop all the flavour. For years where the harvest is exceptional, a millésime is declared and some champagne will be made from and labelled as the products of a single vintage (vintage champagne) rather than a blend of multiple years' harvests. This means that the champagne will be very good and has to mature for at least three years. During this time the champagne bottle is sealed with a crown cap similar to that used on beer bottles.[1]

After aging, the bottle is manipulated, either manually or mechanically, in a process called remuage (or "riddling" in English), so that the lees settle in the neck of the bottle. After chilling the bottles, the neck is frozen, and the cap removed. This process is called disgorgement. The six-bar (600 kPa) pressure[28] in the bottle forces out the ice containing the lees. Some wine from previous vintages and additional sugar (le dosage) is added to maintain the level within the bottle and adjust the sweetness of the finished wine. The bottle is then quickly corked to maintain the carbon dioxide in solution.[1]

Bubbles

[edit]

An initial burst of effervescence occurs when the champagne contacts the dry glass on pouring. These bubbles form on imperfections in the glass that facilitate nucleation or, to a minimal extent, on cellulose fibres left over from the wiping and drying process as shown with a high-speed video camera.[29] However, after the initial rush, these naturally occurring imperfections are typically too small to consistently act as nucleation points as the surface tension of the liquid smooths out these minute irregularities. The nucleation sites that act as a source for the ongoing effervescence are not natural imperfections in the glass, but actually occur where the glass has been etched by the manufacturer or the customer. This etching is typically done with acid, a laser, or a glass etching tool from a craft shop to provide nucleation sites for continuous bubble formation (note that not all glasses are etched in this way). In 1662 this method was developed in England, as records from the Royal Society show.

Dom Pérignon was originally charged by his superiors at the Abbey of Hautvillers to get rid of the bubbles since the pressure in the bottles caused many of them to burst in the cellar.[30] As sparkling wine production increased in the early 18th century, cellar workers had to wear a heavy iron mask to prevent injury from spontaneously bursting bottles. The disturbance caused by one bottle exploding could cause a chain reaction, with it being routine for cellars to lose 20–90% of their bottles this way. The mysterious circumstance surrounding the then unknown process of fermentation and carbonic gas caused some critics to call the sparkling creations "The Devil's Wine".[31]

Champagne producers

[edit]There are more than one hundred champagne houses and 19,000 smaller vignerons (vine-growing producers) in Champagne. These companies manage some 32,000 hectares of vineyards in the region. The type of champagne producer can be identified from the abbreviations followed by the official number on the bottle:[32]

- NM: Négociant manipulant. These companies (including the majority of the larger brands) buy grapes and make the wine

- CM: Coopérative de manipulation. Cooperatives that make wines from the growers who are members, with all the grapes pooled together

- RM: Récoltant manipulant. (Also known as Grower Champagne) A grower that also makes wine from its own grapes (a maximum of 5% of purchased grapes is permitted). Note that co-operative members who take their bottles to be disgorged at the co-op can now label themselves as RM instead of RC

- SR: Société de récoltants. An association of growers making a shared Champagne but who are not a co-operative

- RC: Récoltant coopérateur. A co-operative member selling champagne produced by the co-operative under its own name and label

- MA: Marque auxiliaire or Marque d'acheteur. A brand name unrelated to the producer or grower; the name is owned by someone else, for example a supermarket

- ND: Négociant distributeur. A wine merchant selling under his own name

Marketing

[edit]

In the 19th century, champagne was produced and promoted to mark contemporary political events, such as the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1893, and the Tennis Court Oath to mark the centennial of French Revolution,[33] linking champagne to French nationalist ideology. Négociants also managed to market champagne by identifying it with leisure activities and sporting events. They also successfully appealed to a broader range of consumers by highlighting the different qualities of sparkling wine versus ordinary wine, associating champagne brands with royalty and nobility, and selling off-brands under the names of importers from France at a lower cost. However, selling off-brands at a lower price proved to be unsuccessful, since "there was an assumption that cheap sparkling wine was not authentic."[33] Since the beginning of the Belle Époque period, champagne has gone from a regional product serving a niche market to a national commodity which is distributed globally.

The popularity of champagne is particularly attributed to the success of champagne producers in marketing the wine's image as a royal and aristocratic drink. Laurent-Perrier's advertisements in late 1890 boasted their champagne was the favourite of Leopold II of Belgium, George I of Greece, Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Margaret Cambridge, Marchioness of Cambridge, and John Lambton, 3rd Earl of Durham, among other nobles, knights, and military officers. Despite this royal prestige, champagne houses also portrayed champagne as a luxury which could be enjoyed by anyone, and was fit for any occasion.[34] This strategy worked, and, by the turn of the 20th century, the majority of champagne drinkers were middle class.[35]

In the 19th century, champagne producers made a concentrated effort to market their wine to women. This is done by having the sweeter champagne associates with female, whereas the dry champagne with male and foreign markets.[33] This was in stark contrast to the traditionally "male aura" that the wines of France had—particularly Burgundy and Bordeaux. Laurent-Perrier again took the lead in this area with advertisements touting their wine's favour with the Countess of Dudley, the wife of the 9th Earl of Stamford, the wife of the Baron Tollemache, and the opera singer Adelina Patti. Champagne labels were designed with images of romantic love and marriage as well as other special occasions that were deemed important to women, such as the baptism of a child.[36]

In some advertisements, the champagne houses catered to political interest such as the labels that appeared on different brands on bottles commemorating the centennial anniversary of the French Revolution of 1789. On some labels there were flattering images of Marie Antoinette that appealed to the conservative factions of French citizens that viewed the former queen as a martyr. On other labels there were stirring images of Revolutionary scenes that appealed to the liberal left sentiments of French citizens. As World War I loomed, champagne houses put images of soldiers and countries' flags on their bottles, customizing the image for each country to which the wine was imported. During the Dreyfus affair, one champagne house released a champagne antijuif with antisemitic advertisements to take advantage of the wave of Antisemitism that hit parts of France.[37]

Champagne is typically drunk during celebrations. For example, British Prime Minister Tony Blair held a champagne reception to celebrate London winning the right to host the 2012 Summer Olympics.[38] It is also used to launch ships when a bottle is smashed over the hull during the ship's launch. If the bottle fails to break this is often thought to be bad luck.

Wine districts, grape varieties and styles

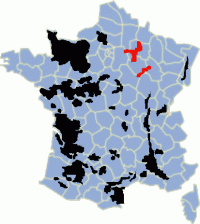

[edit]Wine-producing districts of Champagne

[edit]Champagne is a single appellation d'origine contrôlée but the territory is divided into next sub-regions, known as wine-producing districts, and each of them has distinct characteristics. The main wine-producing districts of the Champagne wine region: Reims, Marne Valley, Côte des Blancs, Côtes des Bar, Côtes de Sezzane.[39]

As a general rule, grapes used must be the white Chardonnay, or the dark-skinned "red wine grapes" Pinot noir or Pinot meunier, which, due to the gentle pressing of the grapes and absence of skin contact during fermentation, usually also yield a white base wine. Most Champagnes, including Rosé wines, are made from a blend of all three grapes, although blanc de blancs ("white from whites") Champagnes are made from 100% Chardonnay and blanc de noirs ("white from blacks") Champagnes are made solely from Pinot noir, Pinot meunier or a mix of the two.[32]

Four other grape varieties are permitted, mostly for historical reasons, as they are rare in current usage. The 2010 version of the appellation regulations lists seven varieties as allowed, Arbane, Chardonnay, Petit Meslier, Pinot blanc, Pinot gris, Pinot meunier, and Pinot noir.[40] The sparsely cultivated varieties (0.02% of the total vines planted in Champagne) of Arbanne, Petit Meslier, and Pinot blanc can still be found in modern cuvées from a few producers.[41] Previous directives of INAO make conditional allowances according to the complex laws of 1927 and 1929, and plantings made before 1938.[42] Before the 2010 regulations, the complete list of the actual and theoretical varieties also included Pinot de Juillet and Pinot Rosé.[43] The Gamay vines of the region were scheduled to be uprooted by 1942, but due to World War II, this was postponed until 1962,[44] and this variety is no longer allowed in Champagne.[40]

The dark-skinned Pinot noir and Pinot meunier give the wine its length and backbone. They are predominantly grown in two areas – the Montagne de Reims and the Vallée de la Marne. The Montagne de Reims run east–west to the south of Reims, in northern Champagne. They are notable for north-facing chalky slopes that derive heat from the warm winds rising from the valleys below. The River Marne runs west–east through Champagne, south of the Montagne de Reims. The Vallée de la Marne contains south-facing chalky slopes. Chardonnay gives the wine its acidity and biscuit flavour. Most Chardonnay is grown in a north–south-running strip to the south of Épernay, called the Côte des Blancs, including the villages of Avize, Oger and Le Mesnil-sur-Oger. These are east-facing vineyards, with terroir similar to the Côte de Beaune. The various terroirs account for the differences in grape characteristics and explain the appropriateness of blending juice from different grape varieties and geographical areas within Champagne, to get the desired style for each Champagne house.[32]

Types of Champagne

[edit]

Most of the Champagne produced today is "Non-vintage", meaning that it is a blended[45] product of grapes from multiple vintages. Most of the base will be from a single year vintage with producers blending anywhere from 10 to 15% (even as high as 40%) of wine from older vintages.[32] If the conditions of a particular vintage are favourable, some producers will make a vintage wine, which must be composed entirely of grapes from that vintage year.[46] Under Champagne wine regulations, houses that make both vintage and non-vintage wines are allowed to use no more than 80% of the total vintage's harvest for the production of vintage Champagne. This allows at least 20% of the harvest from each vintage to be reserved for use in non-vintage Champagne. This ensures a consistent style that consumers can expect from non-vintage Champagne that does not alter too radically depending on the quality of the vintage. In less than ideal vintages, some producers will produce a wine from only that single vintage and still label it as non-vintage rather than as "vintage" since the wine will be of lesser quality and the producers have little desire to reserve the wine for future blending.[32]

Prestige cuvée

[edit]A cuvée de prestige is a proprietary blended wine (usually a Champagne) that is considered to be the top of a producer's range. Famous examples include Louis Roederer's Cristal, Laurent-Perrier's Grand Siècle, Moët & Chandon's Dom Pérignon, Duval-Leroy's Cuvée Femme, Armand de Brignac Gold Brut, and Pol Roger's Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill. Perhaps the first publicly available prestige cuvée was Moët & Chandon's Dom Pérignon, launched in 1936 with the 1921 vintage. Until then, Champagne houses produced different cuvées of varying quality, but a top-of-the-range wine produced to the highest standards (and priced accordingly) was a new idea. In fact, Louis Roederer had been producing Cristal since 1876, but this was strictly for the private consumption of the Russian tsar. Cristal was made publicly available with the 1945 vintage. Then came Taittinger's Comtes de Champagne (first vintage 1952), and Laurent-Perrier's Grand Siècle 'La Cuvée' in 1960, a blend of three vintages (1952, 1953, and 1955) and Perrier Jouët's La Belle Époque. In the last three decades of the 20th century, most Champagne houses followed these with their own prestige cuvées, often named after notable people with a link to that producer and presented in non-standard bottle shapes (following Dom Pérignon's lead with its 18th-century revival design).

Blanc de noirs

[edit]

A French term (literally "white from blacks" or "white of blacks") for a white wine produced entirely from black grapes. The flesh of grapes described as black or red is white; grape juice obtained after minimal possible contact with the skins produces essentially white wine, with a slightly yellower colour than wine from white grapes. The colour, due to the small amount of red skin pigments present, is often described as white-yellow, white-grey, or silvery. Blanc de noirs is often encountered in Champagne, where a number of houses have followed the lead of Bollinger's prestige cuvée Vieilles Vignes Françaises in introducing a cuvée made from either pinot noir, pinot meunier or a blend of the two (these being the only two black grapes permitted within the Champagne AOC appellation).

Blanc de blancs

[edit]

A French term that means "white from whites", and is used to designate Champagnes made exclusively from Chardonnay grapes or in rare occasions from Pinot blanc (such as La Bolorée from Cedric Bouchard). The term is occasionally used in other sparkling wine-producing regions, usually to denote Chardonnay-only wines rather than any sparkling wine made from other white grape varieties.[32]

Rosé Champagne

[edit]Rosé Champagnes are characterized by their distinctive blush color, fruity aroma, and earthy flavor. Rosé Champagne has been produced since the late 18th century; storied French Champagne houses Rinault and Veuve Clicquot have each claimed to have shipped and sold the first bottles.[47] The wine is produced by one of two methods. Using the saignée method, winemakers will leave the clear juice of dark grapes to macerate with the skins for a brief time, resulting in wine lightly colored and flavored by the skins. In the more common d'assemblage method, producers will blend a small amount of still red wine to a sparkling wine cuvée.[48] Champagne is light in color even when it is produced with red grapes, because the juice is extracted from the grapes using a gentle process that minimizes contact with the skins. By contrast, Rosé Champagne, especially that created by d'assemblage, results in the production of rosé with a predictable and reproducible color, allowing winemakers to achieve a consistent rosé appearance from year to year.

The character of rosé Champagne has varied greatly since its production began. Thought to be a sign of extravagance when originally introduced,[49] by the early 20th century these wines were colloquially known as "Pink Champagne," and had gained a reputation of frivolousness or even dissipation. The 1939 Hollywood film Love Affair was reportedly approached to promote it by featuring the main characters bonding over enjoying the unpopular drink, and caused a sales boost after the film's release.[50] It is also cited by the Eagles as a beverage of choice in the titular "Hotel California." Rosé Champagnes, particularly brut varieties, began regaining popularity in the late 20th century in many countries. Because of the complex variety of flavors it presents, rosé Champagne is often served in fine dining restaurants, as a complementary element in food and wine pairing.[32]

Sweetness

[edit]Just after disgorgement a "liqueur de dosage"[51] or liqueur d’expédition – a blend of, typically, cane sugar and wine (sugar amounts up to 750 g/litre) – is added to adjust the levels of sugar in the Champagne when bottled for sale, and hence the sweetness of the finished wine. Today sweetness is generally not looked for per se, and dosage is used to fine tune the perception of acidity in the wine.

For Caroline Latrive, cellar master of Ayala, a Champagne house that pioneered drier champagnes at the end of the 19th century, dosage represents the final touch in champagne making and must be as subtle as possible to bring the right balance.[52]

Additionally, dosage protects champagne from oxidation because it includes a small amount of SO2, and sugar also acts as a preservative. Benoît Gouez, cellar master of Moët & Chandon says that sugar helps champagne recover from the oxidative shock of disgorgement, and contributes to the wine's aging potential.[53]

Wines labeled Brut Zero, more common among smaller producers,[54] have no added sugar and will usually be very dry, with less than three grams of residual sugar per litre in the finished wine. The following terms are used to describe the sweetness of the bottled wine:

- Extra Brut (less than 6 grams of sugar per litre)

- Brut (less than 12 grams)

- Extra Dry (between 12 and 17 grams)

- Sec (between 17 and 32 grams)

- Demi-sec (between 32 and 50 grams)

- Doux (50 grams)

The most common style today is Brut. However, throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century Champagne was generally much sweeter than it is today. Moreover, except in Britain, Champagne was drunk as dessert wines (after the meal), rather than as table wines (with the meal).[55] At this time, Champagne sweetness was instead referred to by destination country, roughly as:[56]

- Goût anglais ("English taste", between 22 and 66 grams); note that today goût anglais refers to aged vintage Champagne

- Goût américain ("American taste", between 110 and 165 grams)

- Goût français ("French taste", between 165 and 200 grams)

- Goût russe ("Russian taste", between 200 and 300 grams)

Of these, only the driest English is close to contemporary tastes.

Bottles

[edit]

Champagne is mostly fermented in two sizes of bottles, standard bottles (750 millilitres) and magnums (1.5 litres). In general, magnums are thought to be higher quality, as there is less oxygen in the bottle, and the volume–to–surface-area ratio favours the creation of appropriately sized bubbles. However, there is no hard evidence for this view. Other bottle sizes, mostly named for Biblical figures, are generally filled with Champagne that has been fermented in standard bottles or magnums. Gosset still bottles its Grande Réserve in Jeroboam from the beginning of its second fermentation.

Sizes larger than Jeroboam (3 L) are rare. Primat bottles (27 L)—and, as of 2002[update], Melchizedek bottles (30 L)—are exclusively offered by the House Drappier. (The same names are used for bottles containing regular wine and port; however, Jeroboam, Rehoboam, and Methuselah refer to different bottle volumes.)[57]

Unique sizes have been made for specific markets, special occasions and people. The most notable example is perhaps the imperial pint (56.8 cL) bottle made between 1874 and 1973 for the English market by Pol Roger, often associated with Sir Winston Churchill.[58]

In 2009, a bottle of 1825 Perrier-Jouët Champagne was opened at a ceremony attended by twelve of the world's top wine tasters. This bottle was officially recognised by Guinness World Records as the oldest bottle of Champagne in the world. The contents were found to be drinkable, with notes of truffles and caramel in the taste. There are now only two other bottles from the 1825 vintage extant.[59]

In July 2010, 168 bottles were found on board a shipwreck near the Åland Islands in the Baltic Sea by Finnish diver Christian Ekström. Initial analyses indicated there were at least two types of bottle from two different houses: Veuve Clicquot in Reims and the long-defunct Champagne house Juglar (absorbed into Jacquesson in 1829.)[60] The shipwreck is dated between 1800 and 1830, and the bottles discovered may well predate the 1825 Perrier-Jouët referenced above.[61][62] When experts were replacing the old corks with new ones, they discovered there were also bottles from a third house, Heidsieck. The wreck, then, contained 95 bottles of Juglar, 46 bottles of Veuve Clicquot, and four bottles of Heidsieck, in addition to 23 bottles whose manufacture is still to be identified. Champagne experts Richard Juhlin and Essi Avellan, MW[60] described the bottles' contents as being in a very good condition. It is planned that the majority of the bottles will be sold at auction, the price of each estimated to be in the region of £40,000–70,000.[61][62][63]

In April 2015, nearly five years after the bottles were first found, researchers led by Philippe Jeandet, a professor of food biochemistry, released the findings of their chemical analyses of the Champagne, and particularly noted the fact that, although the chemical composition of the 170-year-old Champagne was very similar to the composition of modern-day Champagne, there was much more sugar in this Champagne than in modern-day Champagne, and it was also less alcoholic than modern-day Champagne. The high sugar level was characteristic of people's tastes at the time, and Jeandet explained that it was common for people in the 19th century, such as Russians, to add sugar to their wine at dinner. It also contained higher concentrations of minerals such as iron, copper, and table salt than modern-day Champagne does.[64][65]

Champagne corks

[edit]

Champagne corks are mostly built from three sections and are referred to as agglomerated corks. The mushroom shape that occurs in the transition is a result of the bottom section's being composed of two stacked discs of pristine cork cemented to the upper portion, which is a conglomerate of ground cork and glue. The bottom section is in contact with the wine. Before insertion, a sparkling wine cork is almost 50% larger than the opening of the bottle. Originally, the cork starts as a cylinder and is compressed before insertion into the bottle. Over time, their compressed shape becomes more permanent and the distinctive "mushroom" shape becomes more apparent.

The aging of the Champagne post-disgorgement can to some degree be told by the cork, as, the longer it has been in the bottle, the less it returns to its original cylinder shape.

Serving

[edit]Champagne is usually served in a Champagne flute, whose characteristics include a long stem with a tall, narrow bowl, thin sides and an etched bottom. The intended purpose of the shape of the flute is to reduce surface area, therefore preserving carbonation, as well as maximizing nucleation (the visible bubbles and lines of bubbles).[66] Legend has it that the Victorian coupe's shape was modelled on the breast of Madame de Pompadour, chief-mistress of Louis XV of France, or perhaps Marie Antoinette, but the glass was designed in England over a century earlier especially for sparkling wine and champagne in 1663.[67][68] Champagne is always served cold; its ideal drinking temperature is 7 to 9 °C (45 to 48 °F). Often the bottle is chilled in a bucket of ice and water, half an hour before opening, which also ensures the Champagne is less gassy and can be opened without spillage. Champagne buckets are made specifically for this purpose and often have a larger volume than standard wine-cooling buckets to accommodate the larger bottle, and more water and ice.[69]

When it comes to the etiquette behind holding a glass of Champagne, it is important to consider the type of Champagne glass used and the four main parts of any wine glass: the rim, the bowl, the stem and the base. In the case of a flute glass or tulip glass, etiquette dictates holding by the long, narrow stem in order to avoid smudging the glass and warming up the contents with the heat of one's hand. Flute and tulip glasses can be temporarily held by the rim, although this glass hold blocks the area where the taster would take a sip. This hold can also smudge the top section of the glass. These two types of glass can also be held by the disk-shaped base without smudging or warming the liquid inside. When it comes to the coupe glass, with its short stem and shallow, wide-brimmed bowl, the only possible glass hold is by the bowl. The top-heavy nature of the glass makes holding by the base or stem impossible, while the large diameter of the top makes grabbing the glass by the rim difficult.[70]

Opening Champagne bottles

[edit]To reduce the risk of spilling or spraying any Champagne, the bottle is opened by holding the cork and rotating the bottle at an angle in order to ease out the stopper. This method, as opposed to pulling the cork out, prevents the cork from flying out of the bottle at speed (the expanding gases are supersonic).[71] Also, holding the bottle at an angle allows air in and helps prevent the champagne from geysering out of the bottle.

A sabre can be used to open a Champagne bottle with great ceremony. This technique is called sabrage (the term is also used for simply breaking the head of the bottle).[72]

Pouring Champagne

[edit]Pouring sparkling wine while tilting the glass at an angle and gently sliding in the liquid along the side will preserve the most bubbles, as opposed to pouring directly down to create a head of "mousse", according to a study,[73] On the Losses of Dissolved CO2 during Champagne serving, by scientists from the University of Reims.[74] Colder bottle temperatures also result in reduced loss of gas.[74] Additionally, the industry is developing Champagne glasses designed specifically to reduce the amount of gas lost.[75]

Spraying Champagne

[edit]

Champagne has been an integral part of sports celebration since Moët & Chandon started offering their Champagne to the winners of Formula 1 Grand Prix events. At the 1967 24 Hours of Le Mans, winner Dan Gurney started the tradition of drivers spraying the crowd and each other.[76] The Muslim-majority nation Bahrain banned Champagne celebrations on F1 podiums in 2004, using a nonalcoholic pomegranate and rose water drink instead.[77]

In 2015, some Australian athletes, most notably then-Formula 1 Red Bull Racing driver Daniel Ricciardo, began celebrating victories by drinking champagne from their shoe—a practice known as "doing a shoey."

Culinary uses

[edit]The poulet au champagne ("chicken with Champagne") is an essentially Marnese specialty.[78] Other well-known recipes using Champagne are huîtres au champagne ("oysters with Champagne") and Champagne zabaglione.

Price

[edit]There are several general factors influencing the price of Champagne: the limited land of the region, the prestige that Champagne has developed worldwide, and the high cost of the production process, among possible others.[79]

Producers

[edit]A list of major Champagne producers and their respective cuvées de prestige

| House | Founding Year | Location | Cuvée de prestige | Vintage | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henri Abelé | 1757 | Reims | Sourire de Reims |

– | Freixenet Spain |

| Alfred Gratien | 1864 | Épernay | Cuvée Paradis | yes | Henkell & Co. Sektkellerei KG |

| AR Lenoble | 1920 | Damery | Les Aventures | - | Family owned |

| Ayala | 1860 | Aÿ | Grande Cuvée | yes | Bollinger |

| Bauget-Jouette | 1822 | Épernay | Cuvée Jouette/ |

no | Family owned |

| Beaumet/Jeanmaire | 1878 | Épernay | Cuvée Malakoff/ Cuvée Elysée |

yes | Laurent-Perrier |

| Beaumont des Crayères | 1953 | Mardeuil | Nostalgie | dependent | cooperative with ≈240 affiliated producers |

| Besserat de Bellefon | 1843 | Épernay | Cuvée des Moines | – | Groupe Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Billecart-Salmon | 1818 | Mareuil-sur-Ay | Grande Cuvée | yes | independent |

| Binet | 1849 | Rilly-la-Montagne | Cuvée Sélection | yes | Groupe Binet, Prin et Collery |

| Château de Bligny | 1911 | Bligny (Aube) | Cuvée année 2000 | yes | Groupe G. H. Martel & Co. |

| Claude-&-Belmont[permanent dead link] | 1918 | Vertus | Cuvée année 2008 | yes | par CP Récoltant-manipulant |

| Henri Blin et Cie | 1947 | Vincelles | Cuvée Jahr 2000 | yes | cooperative with ≈34 affiliated producers |

| Bollinger | 1829 | Aÿ | Vieilles Vignes Françaises | yes | independent |

| La Grande Année, (R. D. – Récemment Dégorgé, this is the denomination for "Œnothèque" by Bollinger, meaning the crowning achievement of the Grande Année) | yes | ||||

| Boizel | 1834 | Épernay | Joyau de France | yes | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Ferdinand Bonnet | 1922 | Oger | – | – | EPI |

| Raymond Boulard | 1952 | La-Neuville-aux-Larris | Vieilles Vignes | – | independent |

| Canard-Duchêne | 1868 | Ludes | Grande Cuvée Charles VII | – | Alain Thiénot |

| De Castellane | 1895 | Épernay | Commodore | yes | Laurent-Perrier |

| Cattier | 1918 | Chigny-les-Roses | Clos du Moulin/ Armand de Brignac |

– | independent |

| Charles de Cazanove | 1811 | Reims | Stradivarius | – | Groupe Rapeneau |

| Chanoine Frères | 1730 | Reims | gamme Tsarine |

vintage dependent | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Cheurlin | 1788 | Celles-sur-Ource | Brut Spéciale Rosé de Saignée |

- | Independent |

| Cheurlin Thomas | 1788 | Celles-sur-Ource | Blanc de Blanc – Célébrité Blanc de Noir – Le Champion |

- | Independent |

| Deutz | 1838 | Aÿ | Amour de Deutz, Cuvée William Deutz | yes | Louis Rœderer |

| Drappier | 1808 | Urville | Grande Sendrée | yes | family owned

Don perion |

| Duval-Leroy | 1859 | Vertus | Femme de Champagne | vintage dependent | independent |

| Gauthier | 1858 | Épernay | Grande Réserve Brut | – | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Paul Goerg | 1950 | Vertus | Cuvée Lady C. | yes | – |

| Gosset | 1584 | Aÿ | Celebris | yes | Renaud Cointreau |

| Heidsieck & Co. Monopole | 1785 | Épernay | Diamant Bleu | yes | Vranken-Pommery Monopole |

| Charles Heidsieck | 1851 | Reims | Blanc des Millénaires | yes | EPI |

| Henriot | 1808 | Reims | Cuvée des Enchanteleurs | yes | independent |

| Krug | 1843 | Reims | Name defined annually | yes | LVMH |

| Clos du Mesnil, Clos d'Ambonnay | vintage dependent | ||||

| Charles Lafitte | 1848 | Épernay | Orgueil de France | vintage dependent | Vranken-Pommery Monopole |

| Lanson Père & Fils | 1760 | Reims | Noble Cuvée | yes | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Larmandier-Bernier | 1956 | Vertus | Vieille Vigne de Cramant | yes | family owned |

| Laurent-Perrier | 1812 | Tours-sur-Marne | Grand Siècle "La Cuvée" | – | Laurent-Perrier |

| Mercier | 1858 | Épernay | Vendange | yes | LVMH |

| Moët & Chandon | 1743 | Épernay | Dom Pérignon | yes | LVMH |

| G. H. Mumm | 1827 | Reims | Mumm de Cramant | – | Pernod-Ricard |

| Naveau | 1988 | Bergères-les-Vertus | Cuvée Rhapsodie | yes | Family-owned |

| Bruno Paillard | 1981 | Reims | N. P. U. (Nec Plus Ultra) | yes | independent |

| Perrier-Jouët | 1811 | Épernay | Belle Époque | yes | Pernod-Ricard |

| Philipponnat | 1910 | Mareuil-sur-Ay | Clos des Goisses | vintage dependent | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Piper-Heidsieck | 1785 | Reims | Rare | – | EPI |

| Pommery | 1836 | Reims | Cuvée Louise | yes | Vranken-Pommery Monopole |

| Robert Moncuit | 1889 | Le Mesnil-sur-Oger | Cuvée réservée brut, Cuvée réservée extra brut, Grande Cuvée Grand Cru Blanc de Blancs | no | independent |

| Louis Rœderer | 1776 | Reims | Cristal | yes | independent |

| Pol Roger | 1849 | Épernay | Winston Churchill | yes | independent |

| Ruinart | 1729 oldest still active producer |

Reims | Dom Ruinart | yes | LVMH |

| Salon | 1921 | Le Mesnil-sur-Oger | S | yes | Laurent-Perrier |

| Marie Stuart | 1867 | Reims | Cuvée de la Sommelière | – | Alain Thiénot |

| Brut Millésimé | yes | ||||

| Chartogne Taillet | 1515 | Reims | Fiacre | yes | independent |

| Taittinger | 1734 | Reims | Comtes de Champagne | yes | Taittinger |

| Thiénot | 1985 | Reims | Grande Cuvée | yes | Alain Thiénot |

| Cuvée Stanislas | – | ||||

| de Venoge | 1837 | Épernay | Grand Vin des Princes | yes | Boizel Chanoine Champagne |

| Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin | 1772 | Reims | La Grande Dame | yes | LVMH |

| Vranken | 1979 | Épernay | Demoiselle followed by vintage dependent names |

vintage dependent | Vranken-Pommery Monopole |

Shipments

[edit]The Champagne industry is expected to ship 314 million bottles in 2023, down 3.7% from the previous year, according to the Comité Champagne industry trade group. Nightclub markets remain strong, but consumption of Champagne in the home is losing ground.[80]

| Destination | Volume (bottle) |

Value (EUR) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 325.5 million | 6.8 Billion |

| France | 42.5% | 34% |

| Exports | 57.5% | 66% |

| No. | Country | Volume (million bottles) |

Value (million EUR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34.1 | 793.5 | |

| 2 | 29.9 | 503.6 | |

| 3 | 13.8 | 354.5 | |

| 4 | 11.1 | 201.9 | |

| 5 | 10.3 | 200.1 | |

| 6 | 9.9 | 166.9 | |

| 7 | 9.2 | 159.9 | |

| 8 | 6.1 | 125.6 | |

| 9 | 4.4 | 94.0 | |

| 10 | 3.9 | 79.7 |

See also

[edit]- Autolysis (wine)

- Champagne breakfast

- Champagne Riots

- Classification of Champagne vineyards

- Club Trésors de Champagne

- Coteaux Champenois AOC, term used for non-sparkling (still) wines produced in the same area

- List of Champagne houses

- Louis Bohne, sales agent for Veuve Clicquot in the 19th century

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d J. Robinson, ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (Third ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 150–153. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ "Not all wines with bubbles are Champagne". Kentucky Courier-Journal. 13 December 2011.

- ^ Coates, Clive. An Encyclopedia of the Wines and Domaines of France. University of California Press, 2000. pp. 539–40.

- ^ H. Johnson (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine. Simon and Schuster. pp. 210–219. ISBN 0-671-68702-6.

- ^ Christopher Merret Biographical Information. Royal Society website

- ^ Gérard Liger-Belair (2004). Uncorked: The Science of Champagne. Princeton University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-691-11919-9.

- ^ Tom Stevenson (2005). Sotheby's Wine Encyclopaedia. Dorling Kindersley. p. 237. ISBN 0-7513-3740-4.

- ^ McQuillan, Rebecca. "What's the story with ... Champagne?". The Herald. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014.

- ^ Butler, Samuel (1709). Hudibras. The first (second, third) part [by S. Butler]. Corrected and amended, with several additions and annotations.

- ^ "Muselet". Champagne J Dumangin fils. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ "Jaquesson". Cuvées Classiques. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ R. Phillips (2000). A Short History of Wine. HarperCollins. p. 241. ISBN 0-06-621282-0.

- ^ T. Stelzer (2013). The Champagne Guide 2014–2015. Hardie Grant Books. p. 34. ISBN 9781742705415.

- ^ R. Phillips (2000). A Short History of Wine. HarperCollins. p. 242. ISBN 0-06-621282-0.

- ^ Nassauer, Sarah (14 December 2007). "Demand for Champagne gives Peas a chance". The Wall Street Journal. p. B1.

- ^ Boudet, Charles-Henry. "Pourquoi la Champagne va subir son plus grand bouleversement depuis 1927". France 3 Grand Est (in French). Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Sage, Adam. "Champagne region expansion uncorks grapes of wrath". Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Christopher Werth (1 September 2010). "Australia corks its use of 'champagne'". Marketplace. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ^ a b 26 U.S.C. § 5388

- ^ "United States Champagne Bureau Champagne in United States Champagne America". Champagne.us. 31 March 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Oregon State Law 471, including 471.030, 471.730 (1) & (5)

- ^ "Judgment of the Court of 13 December 1994, SMW Winzersekt GmbH v Land Rheinland-Pfalz, Preliminary reference – Assessment of validity – Description of sparkling wines – Prohibition of reference to the method of production known as "méthode champenoise"". Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- ^ Alexandra Stadnyk (10 January 2008). "Belgium destroys California bubbly". BusinessWeek online.

- ^ "Swiss town fights champagne ban". BBC News Online. 5 April 2008.

- ^ Pomranz, Mike (6 July 2021). "Only Wines Made in Russia Can Be Called Champagne Under New Putin Law". Food & Wine. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Russia just banned the use of the word "Shampanskoye" – the Russian word for champagne – on imported bottles". The Peak Magazine. 11 July 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Yeast taste in Champagne". Cellarer.com.

- ^ Matthews, Robert. "How much pressure is there in a champagne bottle?". BBC Science Focus Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021.

- ^ (in French) G. Liger-Belair (2002). "La physique des bulles de champagne" [The physics of the bubbles in Champagne]. Annales de Physique. 27 (4): 1–106. Bibcode:2002AnPh...27d...1L. doi:10.1051/anphys:2002004. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2005.

- ^ D. & P. Kladstrup (November 2005). Champagne. HarperCollins. p. 25. ISBN 0-06-073792-1.

- ^ D. & P. Kladstrup (November 2005). Champagne. HarperCollins. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0-06-073792-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g T. Stevenson, ed. (2005). The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia (4th ed.). Dorling Kindersley. pp. 169–178. ISBN 0-7513-3740-4.

- ^ a b c Guy, Kolleen M. ""Oiling the Wheels of Social Life": Myths and Marketing in Champagne during the Belle Epoque." French Historical Studies 22.2 (1999): 211–39. Web. 28 February 2017.

- ^ R. Phillips (2000). A Short History of Wine. HarperCollins. p. 245. ISBN 0-06-621282-0.

- ^ R. Phillips (2000). A Short History of Wine. HarperCollins. p. 243. ISBN 0-06-621282-0.

- ^ R. Phillips (2000). A Short History of Wine. HarperCollins. p. 246. ISBN 0-06-621282-0.

- ^ R. Phillips (2000). A Short History of Wine. HarperCollins. p. 244. ISBN 0-06-621282-0.

- ^ "Party celebrates 2012 Olympic win". BBC News Online. 31 October 2005.

- ^ "Champagne travel guide for wine lovers". www.winetourism.com. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Décret n° 2010-1441 du 22 novembre 2010 relatif à l'appellation d'origine contrôlée " Champagne "" [Decree number 2010-1441 of 22 November 2010, relating to the Appellation d'Origine Contôlée of 'Champagne'] (in French). Journal officiel de la République française number 273, text number 8. 25 November 2010. p. 21013.

- ^ Rosen, Maggie (8 January 2004). "Champagne house launches '6 grape' cuvée". Decanter.com.

- ^ "AOC Champagne – Conditions de production" (in French). Institut national de l'origine et de la qualité (INAO).

- ^ "AOC Champagne: Définition et loi" [AOC Champagne: Definition and law] (in French). Les Maisons de Champagne.

- ^ Alexis Lichine (1967). Encyclopedia of Wines and Spirits. London: Cassell & Company Ltd. p. 186.

- ^ Eric Pfanner (10 December 2011). "Uncorking the secrets of Champagne". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Media Room | Le site officiel du Champagne". www.champagne.fr. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Napjus, Alison (10 March 2014). "First Rosé Champagne? Older Than You Think". Wine Spectator.

- ^ "How Rosé Champagne is Made". Wine Enthusiast. 8 February 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "That Intoxicating Pink". Lapham’s Quarterly. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Andrea Foshee (21 January 2003). "Love Affair (1939) – Love Affair". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020.

One interesting product placement bit of trivia: The champagne industry was interested in promoting a new product: pink champagne. In one scene, Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne gazed into each others' eyes while sipping on pink champagne, and sales went up immediately afterwards.

- ^ "Dosage – Union des Maisons de Champagne".

- ^ "Dosage in Champagne – Past, Present, Future". BESTCHAMPAGNE. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Interview with Benoît Gouez Chef de Caves of Moët & Chandon". BESTCHAMPAGNE. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Eric Pfanner (21 December 2012). "Champagne Decoded: The Degrees of Sweet". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ Facts About Champagne and Other Sparkling Wines, Henry Vizetelly (1879), pp. 213–214:

"Manufacturers of champagne and other sparkling wines prepare them dry or sweet, light or strong, according to the markets for which they are designed. The sweet wines go to Russia and Germany, the sweet-toothed Muscovite regarding M. Louis Roederer's syrupy product as the beau-idéal of champagne, and the Germans demanding wines with 20 or more per cent. of liqueur, or nearly quadruple the quantity that is contained in the average champagnes shipped to England. France consumes light and moderately sweet wines; the United States gives a preference to the intermediate qualities; China, India, and other hot countries stipulate for light dry wines; while the very strong 214 ones go to Australia, the Cape, and other places where gold and diamonds and such-like trifles are from time to time "prospected." Not merely the driest but the very best wines of the best manufacturers, and commanding of course the highest prices, are invariably reserved for the English market. Foreigners cannot understand the marked preference shown in England for exceedingly dry sparkling wines. They do not consider that as a rule they are drunk during dinner with the plats, and not at dessert, with all kinds of sweets, fruits, and ices, as is almost invariably the case abroad." - ^ Matthews, Ed (10 January 2010). "Goût Américain". One Blog West. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Guide to Champagne Bottle Sizes and Names | Adore Champagne". Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ de Billy, Hubert (25 July 2017). "Liquid history". Berry Bros & Rudd. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "World's oldest champagne opened". BBC News Online. 20 March 2009.

- ^ a b Adam Lechmere (17 November 2010). "Champagne still 'fresh' after nearly two centuries in Baltic". Decanter.com.

- ^ a b Enjoli Liston (18 November 2010). "Champagne still bubbly after 200 years at sea". The Independent. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ a b Louise Nordstrom (17 November 2010). "200-year-old Champagne loses fizz but not flavour". The Washington Post.[dead link]

- ^ "Shipwrecked champagne good, but not ours: Veuve-Clicquot". The Independent. 7 August 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "What Does a 170-Year-Old Champagne Found on the Bottom of the Sea Taste Like?". 21 April 2015.

- ^ Feltman, Rachel (21 April 2015). "170-year-old, shipwrecked champagne gets a taste test". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Ames, D. L., Garrison, J. R., Gitlin, J., Herrmann, G., Isenstadt, S., Jenkins, M., ... & Winn, L. (2014). Shopping: Material Culture Perspectives. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 138–140.

- ^ Lamprey, Zane (16 March 2010). Three Sheets: Drinking Made Easy! 6 Continents, 15 Countries, 190 Drinks, and 1 Mean Hangover!. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-345-52201-6.

- ^ Boehmer, Alan (14 October 2009). Knack Wine Basics: A Complete Illustrated Guide to Understanding, Selecting & Enjoying Wine. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7627-5838-8.

- ^ "Storing and serving Champagne". Cellarer.com.

- ^ Millesima USA, Millesima USA. "How to Hold a Glass of Champagne". Millesima USA.

- ^ Liger-Belair, Gerard; Cordier, Daniel; Georges, Robert (20 September 2019). "Under-expanded supersonic CO2 freezing jets during champagne cork popping". Science Advances. 5 (9): eaav5528. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.5528L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav5528. PMC 6754238. PMID 31555725.

- ^ "How to Open Champagne Bottles". 18 March 2021.

- ^

- Liger-Belair, Gérard; Bourget, Marielle; Villaume, Sandra; Jeandet, Philippe; Pron, Hervé; Polidori, Guillaume (11 August 2010). "On the Losses of Dissolved CO 2 during Champagne Serving" (PDF). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 58 (15): 8768–8775. doi:10.1021/jf101239w. PMID 20681665. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- Liger-Belair, Gérard; Parmentier, Maryline; Cilindre, Clara (28 November 2012). "More on the Losses of Dissolved CO 2 during Champagne Serving: Toward a Multiparameter Modeling". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 60 (47): 11777–11786. doi:10.1021/jf303574m. PMID 23110303. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- Beaumont, Fabien; Liger-Belair, Gérard; Polidori, Guillaume (23 July 2020). "Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) as a Tool for Investigating Self-Organized Ascending Bubble-Driven Flow Patterns in Champagne Glasses". Foods. 9 (8): 972. doi:10.3390/foods9080972. PMC 7466256. PMID 32717781.

- Cilindre, Clara; Henrion, Céline; Coquard, Laure; Poty, Barbara; Barbier, Jacques-Emmanuel; Robillard, Bertrand; Liger-Belair, Gérard (22 July 2021). "Does the Temperature of the prise de mousse Affect the Effervescence and the Foam of Sparkling Wines?". Molecules. 26 (15): 4434. doi:10.3390/molecules26154434. PMC 8347939. PMID 34361583.

- Liger-Belair, Gérard; Villaume, Sandra; Cilindre, Clara; Jeandet, Philippe (11 March 2009). "Kinetics of CO 2 Fluxes Outgassing from Champagne Glasses in Tasting Conditions: The Role of Temperature". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (5): 1997–2003. doi:10.1021/jf803278b. PMID 19215133.

- Liger-Belair, Gérard (2010). "Visual Perception of Effervescence in Champagne and Other Sparkling Beverages". Advances in Food and Nutrition Research. 61: 1–55. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-374468-5.00001-5. ISBN 9780123744685. PMID 21092901.

- Liger-Belair, Gérard; Polidori, Guillaume; Jeandet, Philippe (2008). "Recent advances in the science of champagne bubbles". Chemical Society Reviews. 37 (11): 2490–2911. doi:10.1039/b717798b. PMID 18949122.

- ^ a b Greg Keller (12 August 2010). "Champagne fizzics: Science backs pouring sideways". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "How to pour champagne properly". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ G. Harding (2005). A Wine Miscellany. New York City: Clarkson Potter Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 0-307-34635-8.

- ^ "Bahrain bans champagne". 31 March 2004. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Arbellot, Simon (1963). Tel plat, tel vin (in French). p. 73.

- ^ "The World's Most Expensive Champagnes". Forbes.

- ^ Rascouet, Angelina (17 September 2023). "Champagne Demand Softens After Post-Covid Boom Years, LVMH Says". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Champagne at a glance". Comité Champagne.

Further reading

[edit]- Eichelmann, Gerhard (2017). Champagne – Edition 2017. Heidelberg: Mondo. ISBN 9783938839287.

- Guy, Kolleen M. (2003). When Champagne Became French: Wine and the Making of a National Identity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801887475. OCLC 819135515.

- Liger-Belair, Gérard (2004). Uncorked: The Science of Champagne. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11919-8.

- Stevenson, Tom (2003). World Encyclopedia of Champagne and Sparkling Wine. Wine Appreciation Guild. ISBN 1-891267-61-2.

- Sutcliffe, Serena (1988). Champagne: The History and Character of the World's Most Celebrated Wine. Mitchell Beazley. ISBN 0-671-66672-X.

- Walters, Robert (2016). Bursting Bubbles: A Secret History of Champagne and the Rise of the Great Growers. Abbotsford, Victoria, Australia: Bibendum Wine Co. ISBN 9780646960760.