Blackface

Blackface is the practice of performers using burnt cork, shoe polish, or theatrical makeup to portray a caricature of black people on stage or in entertainment. Scholarship on the origins or definition of blackface vary with some taking a global perspective that includes European culture and Western colonialism.[1] Scholars with this wider view may date the practice of blackface to as early as Medieval Europe's mystery plays when bitumen and coal were used to darken the skin of white performers portraying demons, devils, and damned souls. Still others date the practice to English Renaissance theatre, in works such as William Shakespeare's Othello.

However, some scholars see blackface as a specific practice limited to American culture that began in the minstrel show; a performance art that originated in the United States in the early 19th century and which contained its own performance practices unique to the American stage. Scholars taking this point of view see blackface as arising not from a European stage tradition but from the context of class warfare[2] from within the United States, with the American white working poor inventing blackface as a means of expressing their anger over being disenfranchised economically, politically, and socially from middle and upper class White America.

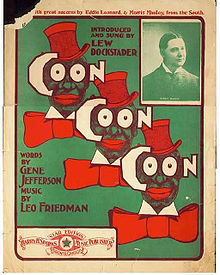

In the United States, the practice of blackface became a popular entertainment during the 19th century into the 20th. It contributed to the spread of racial stereotypes such as "Jim Crow", the "happy-go-lucky darky on the plantation", and "Zip Coon" also known as the "dandified coon".[3][4][2]

By the middle of the 19th century, blackface minstrel shows had become a distinctive American artform, translating formal works such as opera into popular terms for a general audience.[5] Although minstrelsy began with white performers, by the 1840s there were also many all-black cast minstrel shows touring the United States in blackface, as well as black entertainers performing in shows with predominately white casts in blackface. Some of the most successful and prominent minstrel show performers, composers and playwrights were themselves black, such as: Bert Williams, Bob Cole, and J. Rosamond Johnson.

Early in the 20th century, blackface branched off from the minstrel show and became a form of entertainment in its own right,[6] including Tom Shows, parodying abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. In the United States, blackface declined in popularity from the 1940s, with performances dotting the cultural landscape into the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.[7] It was generally considered highly offensive, disrespectful, and racist by the late 20th century,[8] but the practice (or similar-looking ones) was exported to other countries.[9][10]

Early history

[edit]

There is no consensus about a single moment that constitutes the origin of blackface. Arizona State University professor Ayanna Thompson links the beginning of blackface to stage practices within the Medieval Europe miracle or mystery plays. It was common practice in Medieval Europe to use bitumen and soot from coal to darken skin to depict corrupted souls, demons, and devils in blackface. Louisiana State University professor Anthony Barthelemy stated, "“In many medieval miracle plays, the souls of the damned were represented by actors painted black or in black costumes.... In [many versions], Lucifer and his confederate rebels, after having sinned, turn black.”[11]

The journalist and cultural commentator John Strausbaugh places it as part of a tradition of "displaying Blackness for the enjoyment and edification of white viewers" that dates back at least to 1441, when captive West Africans were displayed in Portugal.[12] White people routinely portrayed the black characters in the Elizabethan and Jacobean theater (see English Renaissance theatre), most famously in Othello (1604).[13] However, Othello and other plays of this era did not involve the emulation and caricature of "such supposed innate qualities of Blackness as inherent musicality, natural athleticism", etc. that Strausbaugh sees as crucial to blackface.[12]

A 2023 article appearing on the National Museum of African American History and Culture website, asserts that the birth of blackface is attributable to class warfare:

Historian Dale Cockrell once noted that poor and working-class whites who felt “squeezed politically, economically, and socially from the top, but also from the bottom, invented minstrelsy” as a way of expressing the oppression that marked being members of the majority, but outside of the white norm.[14]

By objectifying formerly enslaved people through demeaning, humor-inducing stock caricatures, "comedic performances of 'blackness' by whites in exaggerated costumes and make-up, [could not] be separated fully from the racial derision and stereotyping at its core".[14] This process of "thingification" has been written about by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, "The whole idea of a stereotype is to simplify",[14] and by Aimé Césaire, "Césaire revealed over and over again the colonizers’ sense of superiority and their sense of mission as the world’s civilizers, a mission that depended on turning the Other into barbarians".[15]

History within the United States

[edit]

Blackface was a performance tradition in the American theater for roughly 100 years beginning around 1830. It was practiced in Britain as well, surviving longer than in the U.S.; The Black and White Minstrel Show on television lasted until 1978.[13]

In both the United States and Britain, blackface was most commonly used in the minstrel performance tradition, which it both predated and outlasted. Early white performers in blackface used burnt cork and later greasepaint or shoe polish to blacken their skin and exaggerate their lips, often wearing woolly wigs, gloves, tailcoats, or ragged clothes to complete the transformation. According to a 1901 source: "Be careful to get the black even around the eyes and mouth. Leave the lips just as they are, they will appear red to the audience. Comedians leave a wide white space all around the lips. It makes the mouth appear larger and will look red as the lips do. If you wish to represent an old darkey, use white drop chalk, outlining the eyebrows, chin, whisk- ers or a gray beard."[16] Later, black artists also performed in blackface. The famous Dreadnought hoax involved the use of blackface and costume for a group of high-profile authors to gain access to a military vessel.[17]

Stereotypes embodied in the stock characters of blackface minstrels not only played a significant role in cementing and proliferating racist images, attitudes, and perceptions worldwide, but also in popularizing black culture.[18] In some quarters, the caricatures that were the legacy of blackface persist to the present day and are a cause of ongoing controversy. Another view is that "blackface is a form of cross-dressing in which one puts on the insignias of a sex, class, or race that stands in opposition to one's own".[19]

By the mid-20th century, changing attitudes about race and racism effectively ended the prominence of blackface makeup used in performance in the U.S. and elsewhere. Blackface in contemporary art remains in relatively limited use as a theatrical device; today, it is more commonly used as social commentary or satire. Perhaps the most enduring effect of blackface is the precedent it established in the introduction of African-American culture to an international audience, albeit through a distorted lens.[20][21] Blackface's appropriation,[20][21][22] exploitation, and assimilation[20] of African-American culture – as well as the inter-ethnic artistic collaborations that stemmed from it – were but a prologue to the lucrative packaging, marketing, and dissemination of African-American cultural expression and its myriad derivative forms in today's world popular culture.[21][23][24]

19th century

[edit]

Lewis Hallam, Jr., a white blackface actor of American Company fame, brought blackface in this more specific sense to prominence as a theatrical device in the United States when playing the role of "Mungo", an inebriated black man in The Padlock, a British play that premiered in New York City at the John Street Theatre on May 29, 1769.[25] The play attracted notice, and other performers adopted the style. From at least the 1810s, blackface clowns were popular in the United States.[26] British actor Charles Mathews toured the U.S. in 1822–23, and as a result added a "black" characterization to his repertoire of British regional types for his next show, A Trip to America, which included Mathews singing "Possum up a Gum Tree", a popular slave freedom song.[27] Edwin Forrest played a plantation black in 1823,[27] and George Washington Dixon was already building his stage career around blackface in 1828,[28] but it was another white comic actor, Thomas D. Rice, who truly popularized blackface. Rice introduced the song "Jump Jim Crow", accompanied by a dance, in his stage act in 1828,[29] and scored stardom with it by 1832.[30]

First on de heel tap, den on the toe

Every time I wheel about I jump Jim Crow.

I wheel about and turn about an do just so,

And every time I wheel about I jump Jim Crow.[31]

Rice traveled the U.S., performing under the stage name "Daddy Jim Crow". The name Jim Crow later became attached to statutes that codified the reinstitution of segregation and discrimination after Reconstruction.[32]

In the 1830s and early 1840s, blackface performances mixed skits with comic songs and vigorous dances. Initially, Rice and his peers performed only in relatively disreputable venues, but as blackface gained popularity they gained opportunities to perform as entr'actes in theatrical venues of a higher class. Stereotyped blackface characters developed: buffoonish, lazy, superstitious, cowardly, and lascivious characters, who stole, lied pathologically, and mangled the English language. Early blackface minstrels were all male, so cross-dressing white men also played black women who were often portrayed as unappealingly and grotesquely mannish, in the matronly mammy mold, or as highly sexually provocative. The 1830s American stage, where blackface first rose to prominence, featured similarly comic stereotypes of the clever Yankee and the larger-than-life Frontiersman;[33] the late 19th- and early 20th-century American and British stage where it last prospered[34] featured many other, mostly ethnically-based, comic stereotypes: conniving Jews;[35][36] drunken brawling Irishmen with blarney;[36][37][38] oily Italians;[36] stodgy Germans;[36] and gullible rural people.[36]

1830s and early 1840s blackface performers performed solo or as duos, with the occasional trio; the traveling troupes that would later characterize blackface minstrelsy arose only with the minstrel show.[39] In New York City in 1843, Dan Emmett and his Virginia Minstrels broke blackface minstrelsy loose from its novelty act and entr'acte status and performed the first full-blown minstrel show: an evening's entertainment composed entirely of blackface performance. (E. P. Christy did more or less the same, apparently independently, earlier the same year in Buffalo, New York.)[40] Their loosely structured show with the musicians sitting in a semicircle, a tambourine player on one end and a bones player on the other, set the precedent for what would soon become the first act of a standard three-act minstrel show.[41] By 1852, the skits that had been part of blackface performance for decades expanded to one-act farces, often used as the show's third act.[42]

In the 1870s the actress Carrie Swain began performing in minstrel shows alongside her husband, the acrobat and blackface performer Sam Swain. It is possible that she was the first woman performer to appear in blackface.[43] Theatre scholar Shirley Staples stated, "Carrie Swain may have been the first woman to attempt the acrobatic comedy typical of male blackface work."[44] She later portrayed the blackface role of Topsy in a musical adaptation of Harriet Beecher Stowe anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin by composer Caryl Florio and dramatist H. Wayne Ellis. It premiered at the Chestnut Street Opera House in Philadelphia on May 22, 1882.[45]

The songs of Northern composer Stephen Foster figured prominently in blackface minstrel shows of the period. Though written in dialect and politically incorrect by modern standards, his later songs were free of the ridicule and blatantly racist caricatures that typified other songs of the genre. Foster's works treated slaves and the South in general with sentimentality that appealed to audiences of the day.[46]

White minstrel shows featured white performers pretending to be black people, playing their versions of 'black music' and speaking ersatz black dialects. Minstrel shows dominated popular show business in the U.S. from that time through into the 1890s, also enjoying massive popularity in the UK and in other parts of Europe.[47] As the minstrel show went into decline, blackface returned to its novelty act roots and became part of vaudeville.[34] Blackface featured prominently in film at least into the 1930s, and the "aural blackface"[48] of the Amos 'n' Andy radio show lasted into the 1950s.[48] Meanwhile, amateur blackface minstrel shows continued to be common at least into the 1950s.[49] In the UK, one such blackface popular in the 1950s was Ricardo Warley from Alston, Cumbria who toured around the North of England with a monkey called Bilbo.[50]

As a result, the genre played an important role in shaping perceptions of and prejudices about black people generally and African Americans in particular. Some social commentators have stated that blackface provided an outlet for white peoples' fear of the unknown and the unfamiliar, and a socially acceptable way of expressing their feelings and fears about race and control. Writes Eric Lott in Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class: "The black mask offered a way to play with the collective fears of a degraded and threatening – and male – Other while at the same time maintaining some symbolic control over them."[51]

Blackface, at least initially, could also give voice to an oppositional dynamic that was prohibited by society. As early as 1832, Thomas D. Rice was singing: "An' I caution all white dandies not to come in my way, / For if dey insult me, dey'll in de gutter lay." It also on occasion equated lower-class white and lower-class black audiences; while parodying Shakespeare, Rice sang, "Aldough I'm a black man, de white is call'd my broder."[52]

20th century

[edit]

In the early years of film, black characters were routinely played by white people in blackface. In the first filmic adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin (1903), all of the major black roles were white people in blackface.[53] Even the 1914 Uncle Tom starring African-American actor Sam Lucas in the title role had a white male in blackface as Topsy.[54] D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation (1915) used white people in blackface to represent all of its major black characters,[55] but reaction against the film's racism largely put an end to this practice in dramatic film roles. Thereafter, white people in blackface would appear almost exclusively in broad comedies or "ventriloquizing" blackness[56] in the context of a vaudeville or minstrel performance within a film.[57] This stands in contrast to made-up white people routinely playing Native Americans, Asians, Arabs, and so forth, for several more decades.[58]

From the 1910s up until the early 1950s, many well-known entertainers of stage and screen also performed in blackface.[59] Light-skinned people who performed in blackface in film included Al Jolson,[60] Eddie Cantor,[61] Bing Crosby,[60] Fred Astaire, Buster Keaton, Joan Crawford, Irene Dunne, Doris Day, Milton Berle, William Holden, Marion Davies, Myrna Loy, Betty Grable, Dennis Morgan, Laurel and Hardy, Betty Hutton, The Three Stooges, The Marx Brothers, Mickey Rooney, Shirley Temple, Judy Garland, Donald O'Connor and Chester Morris and George E. Stone in several of the Boston Blackie films.[61] In 1936, when Orson Welles was touring his Voodoo Macbeth; the lead actor, Maurice Ellis, fell ill, so Welles stepped into the role, performing in blackface.[62]

As late as the 1940s, Warner Bros. used blackface in Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), a minstrel show sketch in This Is the Army (1943) and by casting Flora Robson as a Haitian maid in Saratoga Trunk (1945).[63] In The Spoilers (1942), John Wayne appeared in blackface and bantered in a mock accent with a black maid who mistook him for an authentic black man.

In Holiday Inn (film), Bing Crosby and Marjorie Reynolds

- sang “Abraham,” a song honoring Lincoln’s birthday, in shoe-polish blackface. The band behind them and the waiters were also in blackface.[64]

Blackface makeup was largely eliminated even from live-action film comedy in the U.S. after the end of the 1930s, when public sensibilities regarding race were beginning to change and blackface became increasingly associated with racism and bigotry.[7] Still, the tradition did not end all at once. The radio program Amos 'n' Andy (1928–1960) constituted a type of "oral blackface", in that the black characters were portrayed by white people and conformed to stage blackface stereotypes.[65] The conventions of blackface also lived on unmodified at least into the 1950s in animated theatrical cartoons. Strausbaugh estimates that roughly one-third of late 1940s MGM cartoons "included a blackface, coon, or mammy figure".[66] Bugs Bunny appeared in blackface at least as late as Southern Fried Rabbit in 1953.[67]

Singer Grace Slick was wearing blackface when her band Jefferson Airplane performed "Crown of Creation" and "Lather" at The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1968. A clip is included in a 2004 documentary Fly Jefferson Airplane, directed by Bob Sarles.

The 1976 action comedy Silver Streak included a farcical scene in which Gene Wilder must impersonate a black man, as instructed by Richard Pryor. In 1980, an underground film, Forbidden Zone, was released, directed by Richard Elfman and starring the band Oingo Boingo, which received controversy for blackface sequences.[68]

Also in 1980, the white members of UB40 appeared in blackface in their "Dream a Lie" video, while the black members appeared in whiteface to give the opposite appearance.[69]

Trading Places (1983) is a film telling the elaborate story of a commodities banker and street hustler crossing paths after being made part of a bet. The film features a scene between Eddie Murphy, Jamie Lee Curtis, Denholm Elliott, and Dan Aykroyd when they must don disguises to enter a train. Aykroyd's character puts on full blackface make-up, a dreadlocked wig and a Jamaican accent to fill the position of a Jamaican pothead. The film, being an obvious satire, has received little criticism for its use of racial and ethnic stereotype due to it mocking the ignorance of Aykroyd's character rather than black people as a whole, with Rotten Tomatoes citing it as "featuring deft interplay between Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd, Trading Places is an immensely appealing social satire".[70]

Soul Man is a 1986 film featuring C. Thomas Howell as Mark Watson, a pampered rich white college graduate who uses "tanning pills" to qualify for a scholarship to Harvard Law only available to African American students. He expects to be treated as a fellow student and instead learns the isolation of 'being black' on campus. He later befriends and falls in love with the original candidate of the scholarship, a single mother who works as a waitress to support her education. He later "comes out" as white, leading to the famous defending line: "Can you blame him for the color of his skin?" Unlike Trading Places, the film was met with heavy criticism of a white man donning blackface to humanize white ignorance at the expense of African American viewers. Despite a large box office intake, it has scored low on every film critic platform. "A white man donning blackface is taboo," said Howell; "Conversation over – you can't win. But our intentions were pure: We wanted to make a funny movie that had a message about racism."[71]

Parades

[edit]In the early 20th century, a group of African American laborers began a marching club in the New Orleans Mardi Gras parade, dressed as hobos and calling themselves "The Tramps". Wanting a flashier look, they renamed themselves "Zulus" and copied their costumes from a blackface vaudeville skit performed at a local black jazz club and cabaret.[72] The result is one of the best known and most striking krewes of Mardi Gras, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. Dressed in grass skirts, top hat and exaggerated makeup, the Zulus of New Orleans are controversial as well as popular.[73] The group has, since the 1960s, argued that the black and white makeup they continue to wear is not blackface.

The wearing of blackface was once a regular part of the annual Mummers Parade in Philadelphia. Growing dissent from civil rights groups and the offense of the black community led to a 1964 city policy, ruling out blackface.[74] Despite the ban on blackface, brownface was still used in the parade in 2016 to depict Mexicans, causing outrage once again among civil rights groups.[75] Also in 1964, bowing to pressure from the interracial group Concern, teenagers in Norfolk, Connecticut, reluctantly agreed to discontinue using blackface in their traditional minstrel show that was a fundraiser for the March of Dimes.[76]

21st century

[edit]

Commodities bearing iconic "darky" images, from tableware, soap and toy marbles to home accessories and T-shirts, continue to be manufactured and marketed. Some are reproductions of historical artifacts ("negrobilia"), while others are designed for today's marketplace ("fantasy"). There is a thriving niche market for such items in the U.S., particularly. The value of the original examples of darky iconography (vintage negrobilia collectables) has risen steadily since the 1970s.[77]

There have been several inflammatory incidents of white college students donning blackface. Such incidents usually escalate around Halloween, with students accused of perpetuating racial stereotypes.[78][79][80][81]

In 1998, Harmony Korine released The Diary of Anne Frank Pt II, a 40-minute three-screen collage featuring a man in blackface dancing and singing "My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean".[82]

Blackface and minstrelsy serve as the theme of African American director Spike Lee's film Bamboozled (2000). It tells of a disgruntled black television executive who reintroduces the old blackface style in a series concept in an attempt to get himself fired and is instead horrified by its success.

In 2000, Jimmy Fallon performed in blackface on Saturday Night Live, imitating former cast member Chris Rock.[83] That same year, Harmony Korine directed the short film Korine Tap for Stop For a Minute, a series of short films commissioned by Dazed & Confused magazine and FilmFour Lab. The film featured Korine tap dancing while wearing blackface.[84][85]

Jimmy Kimmel donned black paint and used an exaggerated, accented voice to portray NBA player Karl Malone on The Man Show in 2003. Kimmel repeatedly impersonated the NBA player on The Man Show and even made an appearance on Crank Yankers using his exaggerated Ebonics/African-American Vernacular English to prank call about Beanie Babies.

In November 2005, controversy erupted when journalist Steve Gilliard posted a photograph on his blog. The image was of African American Michael Steele, a politician, then a candidate for U.S. Senate. It had been doctored to include bushy, white eyebrows and big, red lips. The caption read, "I's simple Sambo and I's running for the big house." Gilliard, also African-American, defended the image, commenting that the politically conservative Steele has "refused to stand up for his people".[86] (See Uncle Tom § Epithet.)

In a 2006 reality television program, Black. White., white participants wore blackface makeup and black participants wore whiteface makeup in an attempt to be better able to see the world through the perspective of the other race.[87]

In 2007, Sarah Silverman performed in blackface for a skit from The Sarah Silverman Program.[88]

A Mighty Heart is a 2007 American film featuring Angelina Jolie playing Mariane Pearl, the wife of the kidnapped Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl. Mariane is of multiracial descent, born from an Afro-Chinese-Cuban mother and a Dutch Jewish father. She personally cast Jolie to play herself, defending the choice to have Jolie "sporting a spray tan and a corkscrew wig".[89] Criticism of the film came in large part for the choice to have Jolie portraying Mariane Pearl in this manner. Defense of the casting choice was in large part due to Pearl's mixed racial heritage, critics claiming it would have been impossible to find an Afro-Latina actress with the same crowd-drawing caliber of Jolie. Director Michael Winterbottom defended his casting choice in an interview, "To try and find a French actress who's half-Cuban, quarter-Chinese, half-Dutch who speaks great English and could do that part better – I mean, if there had been some more choices, I might have thought, 'Why don't we use that person?'...I don't think there would have been anyone better."[90]

A 2008 imitation of Barack Obama by American comedian Fred Armisen (of German, Korean, and Venezuelan descent) on the popular television program Saturday Night Live caused some stir, with The Guardian's commentator asking why SNL did not hire an additional black actor to do the sketch; the show had only one black cast member at the time.[91]

Also in 2008, Robert Downey Jr.'s character Kirk Lazarus appeared in brownface in the Ben Stiller-directed film Tropic Thunder. As with Trading Places, the intent was satire; specifically, blackface was ironically employed to humorously mock one of the many foibles of Hollywood rather than black people themselves. Downey was even nominated for an Oscar for his portrayal.[92] According to Downey, "90 per cent of my black friends were like, 'Dude, that was great.' I can't disagree with [the other 10 per cent], but I know where my heart lies."[93]

In the November 2010 episode "Dee Reynolds: Shaping America's Youth", the TV show It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia comically explored if blackface could ever be done "right". One of the characters, Frank Reynolds insists that Laurence Olivier's blackface performance in his 1965 production of Othello was not offensive, while Dennis claimed it "distasteful" and "never okay". In the same episode, the gang shows their fan film, Lethal Weapon 5, in which the character Mac appears in blackface.[94] In the season 9 episode "The Gang make Lethal Weapon 6", Mac once again dons black make-up, along with Dee, who plays his character's daughter in the film. Later in the series, the episode "The Gang Makes Lethal Weapon 7" addresses the topic again along with the removal of their films from the library.

A 2012 Popchips commercial showing actor Ashton Kutcher with brown make-up on his face impersonating a stereotypical Indian person generated controversy and was eventually pulled by the company after complaints of racism.[95] In the TV series Mad Men, set in the 1960s in New York City, the character Roger Sterling appears in blackface in the season 3 episode "My Old Kentucky Home". Julianne Hough attracted controversy in October 2013 when she donned blackface as part of a Halloween costume depicting the character of "Crazy Eyes" from Orange Is the New Black.[96][97] Hough later apologized, stating on Twitter: "I realize my costume hurt and offended people and I truly apologize."[98]

Billy Crystal impersonated Sammy Davis Jr. in the 2012 Oscars opening montage. The scene depicts Crystal in black face paint wearing an oiled wave wig while talking to Justin Bieber. In the scene Crystal leaves a parting remark to Bieber, "Have fun storming the Führer", a poor association to his famous line in The Princess Bride, "Have fun storming the castle." The skit was remarked as poor taste, considering he was chosen as the "safer" choice after Eddie Murphy bowed out following producer and creative partner Brett Ratner's homophobic remarks.[99][100]

Victoria Foyt was accused of using blackface in the trailer for her young adult novel Save the Pearls: Revealing Eden as well as in the book and its artwork.[101][102]

Performer Chuck Knipp (who is white and gay) has used drag, blackface, and broad racial caricature to portray a character named "Shirley Q. Liquor" in his cabaret act, generally performed for all-white audiences. Knipp's outrageously stereotypical character has drawn criticism and prompted demonstrations from Black, Gay and transgender activists.[103]

The Metropolitan Opera, based in New York City, used blackface in productions of the opera Otello until 2015,[104][105][106] though some have argued that the practice of using dark makeup for the character did not qualify as blackface.[107]

On February 1, 2019, images from Governor of Virginia Ralph Northam's medical school yearbook were published on the far-right website Big League Politics.[108][109][110] The photos showed an image of Northam in blackface and an unidentified person in a Ku Klux Klan hood on Northam's page in the yearbook.[111][112][113] A spokesman for Eastern Virginia Medical School confirmed that the image appeared in its 1984 yearbook.[114] Shortly after the news broke, Northam apologized for appearing in the photo.[114]

Blackface performances are not unusual within the Latino community of Miami. As Spanish-speakers from different countries, ethnic, racial, class, and educational backgrounds settle in the United States, they have to grapple with being re-classified vis-a-vis other American-born and immigrant groups. Blackface performances have, for instance, tried to work through U.S. racial and ethnic classifications in conflict with national identities. A case in point is the representation of Latino and its popular embodiment as a stereotypical Dominican man.[115]

In the wake of protests over the treatment of African-Americans following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, episodes of popular television programs featuring characters in blackface were pulled from circulation. This includes The Golden Girls, The Office, It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, 30 Rock, Community, and Scrubs, among others.[116]

Stunt doubles

[edit]White men are the main source of stunt doubles in American TV and film productions. The practice of a male performer portraying standing-in for a female actor is known as "wigging". When the stunt performer is made up to look like another race, the practice is called a "paint down". Stunt performers Janeshia Adams-Ginyard and Sharon Schaffer have equated it in 2018 with blackface minstrelsy.[117]

Digital media

[edit]Digital media provide opportunities to inhabit and perform Black identity without actually painting one's face, which, in a way, some critics have likened to blackface and minstrelsy. In 1999, Adam Clayton Powell III coined the term "high-tech blackface" to refer to stereotypical portrayals of black characters in video games.[118] David Leonard writes, "The desire to 'be Black' because of the stereotypical visions of strength, athleticism, power and sexual potency all play out within the virtual reality of sports games." Leonard's argument suggests that players perform a type of identity tourism by controlling Black avatars in sports games.[119] Phillips and Reed argue that this type of blackface "is not only about whites assuming Black roles, nor about exaggerated performances of blackness for the benefit of a racist audience. Rather, it is about performing a version of blackness that constrains it within the boundaries legible to white supremacy."[120]

In addition, writers such as Lauren Michele Jackson, Victoria Princewill and Shafiqah Hudson criticized non-Black people sharing animated images, or GIFs, of Black people or Black-skinned emojis, calling the practice "digital blackface".[121][122][123] Writers Amanda Hess and Shane O'Neill have elaborated on their work, pointing out that GIFs of women of color, in particular, have been most frequently used to express user's emotions online. Hess and O'Neill also suggest that the emoji app Bitmoji uses "black emotional reactions and verbal expressions" and designs them to fit non-Black bodies and faces. Writer Manuel Arturo Abreu refers to this phenomenon as "online imagined Black English", where non-Black users engage in African American Vernacular English, or AAVE, on the internet without understanding the full context of the particular phrase being used.[124]

Following these critiques, the term "digital blackface" has since evolved with the rise of other social media and digital media technologies. In 2020, writer Francesa Sobande wrote on the digital representations of Black people, defining digital blackface as "encompassing online depictions and practices that echo the anti-Black underpinnings of minstrelsy shows involving non-Black people 'dressing up' and 'performing' as though they are Black". Sobande's argument suggests that this acts as a "digital expression of the oppression that Black people face" outside of the internet, where they can be viewed as an objectified type of "commodity or labor tool".[125]

Since the criticisms made by these writers, instances of digital blackface have varied in type across the internet. In 2016, a controversy emerged over social media app Snapchat's Bob Marley filter, which allowed users to superimpose dark skin, dreadlocks, and a knitted cap over their own faces.[126][127] A number of controversies have also emerged about students at American universities sharing images of themselves appearing to wear blackface makeup.[128][129][130][131] In 2020, two high school students in Georgia were expelled after posting a "racially insensitive" TikTok video that used racial slurs and stereotypes about Black people.[132][133]

Senior writer Jason Parham suggests that the social media app TikTok, and its viral trends and challenges, has become a new medium for 21st century minstrelsy. Parham argues that "unlike Facebook and Twitter, where instances of digital blackface are either text-based or image-based, TikTok is a video-first platform" where "creators embody Blackness with an auteur-driven virtuosity—taking on Black rhythms, gestures, affect, slang". Examples of these controversial trends and challenges have included "the Hot Cheeto Girl", which is said to mimic stereotypes of Black and Latin women, the "#HowsMyForm" challenge, which plays on racist stereotypes of Black people and other racial groups, and other perceived instances of cultural appropriation, such as "blackfishing".[134][135][136]

In 2021, conversation around digital blackface gained further traction after Oprah Winfrey's interview with Meghan Markle and Prince Harry, where Winfrey's reactions during the interview began to circulate the internet in the form of memes. A widespread Instagram post by the Slow Factory Foundation, an activist group founded by Céline Semaan Vernon, calling attention to digital blackface led to many critiques and criticisms about whether or not it was appropriate for non-Black people to continue sharing these images of Winfrey.[137][138][139]

Universities

[edit]In 2021, music professor Bright Sheng stepped down from teaching a University of Michigan musical composition class, where he says he had intended to show how Giuseppe Verdi adapted William Shakespeare's play Othello into his opera Otello, after showing the 1965 British movie Othello, whose actors received 4 Oscar nominations, but in which the white actor Laurence Olivier played Othello in blackface, which caused controversy even at the time.[140][141][142] Sheng allegedly failed to give students any warning that the movie contained blackface, and his two subsequent apologies failed to satisfy his critics, with the wording of the second one causing further controversy.[140][142] There was disagreement over whether showing the blackface performance constituted racism.[140][143] Evan Chambers, a professor of composition (as is Sheng), said "To show the film now, especially without substantial framing, content advisory and a focus on its inherent racism is in itself a racist act, regardless of the professor's intentions",[140] while David Gier, dean of the School of Music, Theatre & Dance, said: "Professor Sheng's actions do not align with our School's commitment to anti-racist action, diversity, equity and inclusion"[142] But Robert Soave, a senior editor at Reason magazine, said that the university had violated the principle of academic freedom, that showing the movie was neither a racist act nor approval of racism, and that the university owed Sheng an apology for unfairly maligning him, and he compared it to Sheng's earlier experience of surviving the Chinese Cultural Revolution.[140]

Black performers in blackface

[edit]

19th century

[edit]By 1840, black performers also were performing in blackface makeup. Frederick Douglass generally abhorred blackface and was one of the first people to write against the institution of blackface minstrelsy, condemning it as racist in nature, with inauthentic, northern, white origins.[144] Douglass did, however, maintain: "It is something to be gained when the colored man in any form can appear before a white audience."[145]

When all-black minstrel shows began to proliferate in the 1860s, they often were billed as "authentic" and "the real thing". These "colored minstrels"[146] always claimed to be recently freed slaves (doubtlessly many were, but most were not)[147] and were widely seen as authentic. This presumption of authenticity could be a bit of a trap, with white audiences seeing them more like "animals in a zoo"[148] than skilled performers. Despite often smaller budgets and smaller venues, their public appeal sometimes rivaled that of white minstrel troupes. In March 1866, Booker and Clayton's Georgia Minstrels may have been the country's most popular troupe, and were certainly among the most critically acclaimed.[149]

These "colored" troupes – many using the name "Georgia Minstrels"[150] – focused on "plantation" material, rather than the more explicit social commentary (and more nastily racist stereotyping) found in portrayals of northern black people.[151] In the execution of authentic black music and the percussive, polyrhythmic tradition of pattin' Juba, when the only instruments performers used were their hands and feet, clapping and slapping their bodies and shuffling and stomping their feet, black troupes particularly excelled. One of the most successful black minstrel companies was Sam Hague's Slave Troupe of Georgia Minstrels, managed by Charles Hicks. This company eventually was taken over by Charles Callendar. The Georgia Minstrels toured the United States and abroad and later became Haverly's Colored Minstrels.[149]

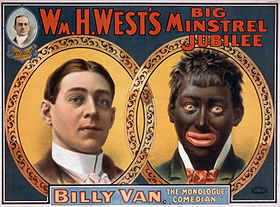

From the mid-1870s, as white blackface minstrelsy became increasingly lavish and moved away from "Negro subjects", black troupes took the opposite tack.[152] The popularity of the Fisk Jubilee Singers and other jubilee singers had demonstrated northern white interest in white religious music as sung by black people, especially spirituals. Some jubilee troupes pitched themselves as quasi-minstrels and even incorporated minstrel songs; meanwhile, blackface troupes began to adopt first jubilee material and then a broader range of southern black religious material. Within a few years, the word "jubilee", originally used by the Fisk Jubilee Singers to set themselves apart from blackface minstrels and to emphasize the religious character of their music, became little more than a synonym for "plantation" material.[153] Where the jubilee singers tried to "clean up" Southern black religion for white consumption, blackface performers exaggerated its more exotic aspects.[154]

African-American blackface productions also contained buffoonery and comedy, by way of self-parody. In the early days of African-American involvement in theatrical performance, black people could not perform without blackface makeup, regardless of how dark-skinned they were. The 1860s "colored" troupes violated this convention for a time: the comedy-oriented endmen "corked up", but the other performers "astonished" commentators by the diversity of their hues.[155] Still, their performances were largely in accord with established blackface stereotypes.[156]

These black performers became stars within the broad African-American community, but were largely ignored or condemned by the black bourgeoisie. James Monroe Trotter – a middle-class African American who had contempt for their "disgusting caricaturing" but admired their "highly musical culture" – wrote in 1882 that "few ... who condemned black minstrels for giving 'aid and comfort to the enemy'" had ever seen them perform.[157] Unlike white audiences, black audiences presumably always recognized blackface performance as caricature, but took pleasure in seeing their own culture observed and reflected, much as they would half a century later in the performances of Moms Mabley.[158]

Despite reinforcing racist stereotypes, blackface minstrelsy was a practical and often relatively lucrative livelihood when compared to the menial labor to which most black people were relegated. Owing to the discrimination of the day, "corking (or blacking) up" provided an often singular opportunity for African-American musicians, actors, and dancers to practice their crafts.[159] Some minstrel shows, particularly when performing outside the South, also managed subtly to poke fun at the racist attitudes and double standards of white society or champion the abolitionist cause. It was through blackface performers, white and black, that the richness and exuberance of African-American music, humor, and dance first reached mainstream, white audiences in the U.S. and abroad.[21] It was through blackface minstrelsy that African American performers first entered the mainstream of American show business.[160] Black performers used blackface performance to satirize white behavior. It was also a forum for the sexual double entendre gags that were frowned upon by white moralists. There was often a subtle message behind the outrageous vaudeville routines:

The laughter that cascaded out of the seats was directed parenthetically toward those in America who allowed themselves to imagine that such 'nigger' showtime was in any way respective of the way we live or thought about ourselves in the real world.[161]: 5, 92–92, 1983 ed.

20th century

[edit]With the rise of vaudeville, Bahamian-born actor and comedian Bert Williams became Florenz Ziegfeld's highest-paid star and only African American star.[162][163]

In the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA), an all-black vaudeville circuit organized in 1909, blackface acts were a popular staple. Called "Toby" for short, performers also nicknamed it "Tough on Black Actors" (or, variously, "Artists" or "Asses"), because earnings were so meager. Still, TOBA headliners like Tim Moore and Johnny Hudgins could make a very good living, and even for lesser players, TOBA provided fairly steady, more desirable work than generally was available elsewhere. Blackface served as a springboard for hundreds of artists and entertainers – black and white – many of whom later would go on to find work in other performance traditions. For example, one of the most famous stars of Haverly's European Minstrels was Sam Lucas, who became known as the "Grand Old Man of the Negro Stage".[164] Lucas later played the title role in the 1914 cinematic production of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin.

From the early 1930s to the late 1940s, New York City's famous Apollo Theater in Harlem featured skits in which almost all black male performers wore the blackface makeup and huge white painted lips, despite protests that it was degrading from the NAACP. The comics said they felt "naked" without it.[161]: 4, 1983 ed.

The minstrel show was appropriated by the black performer from the original white shows, but only in its general form. Black people took over the form and made it their own. The professionalism of performance came from black theater. Some argue that the black minstrels gave the shows vitality and humor that the white shows never had. As the black social critic LeRoi Jones has written:

It is essential to realize that ... the idea of white men imitating, or caricaturing, what they consider certain generic characteristics of the black man's life in America is important if only because of the Negro's reaction to it. (And it is the Negro's reaction to America, first white and then black and white America, that I consider to have made him such a unique member of this society.)[165]

The black minstrel performer was not only poking fun at himself but in a more profound way, he was poking fun at the white man. The cakewalk is caricaturing white customs, while white theater companies attempted to satirize the cakewalk as a black dance. Again, as LeRoi Jones notes:

If the cakewalk is a Negro dance caricaturing certain white customs, what is that dance when, say, a white theater company attempts to satirize it as a Negro dance? I find the idea of white minstrels in blackface satirizing a dance satirizing themselves a remarkable kind of irony – which, I suppose is the whole point of minstrel shows.[165]

Puerto Rico

[edit]During the 20th century, blackface was not an uncommon sight at parades in Puerto Rico.[166] In 2019, when blackface was prominently featured at a carnival in San Sebastián, Puerto Rico, the town immediately faced backlash and criticism.[167]

Authenticity

[edit]The degree to which blackface performance drew on authentic black culture and traditions is controversial. Black people, including slaves, were influenced by white culture, including white musical culture. Certainly this was the case with church music from very early times. Complicating matters further, once the blackface era began, some blackface minstrel songs unquestionably written by New York-based professionals (Stephen Foster, for example) made their way to the plantations in the South and merged into the body of black folk music.[168]

It seems clear, however, that American music by the early 19th century was an interwoven mixture of many influences, and that blacks were quite aware of white musical traditions and incorporated these into their music.

In the early years of the nineteenth century, white-to-black and black-to-white musical influences were widespread, a fact documented in numerous contemporary accounts.... [I]t becomes clear that the prevailing musical interaction and influences in nineteenth century America produced a black populace conversant with the music of both traditions.[169]

Early blackface minstrels often said that their material was largely or entirely authentic black culture; John Strausbaugh, author of Black Like You, said that such claims were likely to be untrue. Well into the 20th century, scholars took the stories at face value.[170] Constance Rourke, one of the founders of what is now known as cultural studies, largely assumed this as late as 1931.[171] In the Civil Rights era there was a strong reaction against this view, to the point of denying that blackface was anything other than a white racist counterfeit.[172] Starting no later than Robert Toll's Blacking Up (1974), a "third wave" has systematically studied the origins of blackface, and has put forward a nuanced picture: that blackface did, indeed, draw on black culture, but that it transformed, stereotyped, and caricatured that culture, resulting in often racist representations of black characters.[173]

As discussed above, this picture becomes even more complicated after the Civil War, when many blacks became blackface performers. They drew on much material of undoubted slave origins, but they also drew on a professional performer's instincts, while working within an established genre, and with the same motivation as white performers to make exaggerated claims of the authenticity of their own material.

Author Strausbaugh summed up as follows: "Some minstrel songs started as Negro folk songs, were adapted by White minstrels, became widely popular, and were readopted by Blacks." "The question of whether minstrelsy was white or black music was moot. It was a mix, a mutt – that is, it was American music."[174]

"Darky" iconography

[edit]

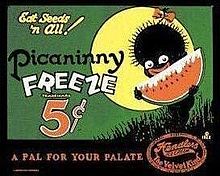

The darky icon itself – googly-eyed, with inky skin, exaggerated white, pink or red lips, and bright, white teeth – became a common motif in entertainment, children's literature, mechanical banks, and other toys and games of all sorts, cartoons and comic strips, advertisements, jewelry, textiles, postcards, sheet music, food branding and packaging, and other consumer goods.

In 1895, the Golliwog surfaced in Great Britain, the product of children's book illustrator Florence Kate Upton, who modeled her rag doll character after a minstrel doll from her American childhood. "Golly", as he later affectionately came to be called, had a jet-black face, wild, woolly hair, bright, red lips, and sported formal minstrel attire. The generic British golliwog later made its way back across the Atlantic as dolls, toy tea sets, ladies' perfume, and in a myriad of other forms. The word "golliwog" may have given rise to the ethnic slur "wog".[176]

U.S. cartoons from the 1930s and 1940s often featured characters in blackface gags as well as other racial and ethnic caricatures. The United Artists 1933 release "Mickey's Mellerdrammer" – the name a corruption of "melodrama" thought to harken back to the earliest minstrel shows – was a film short based on a production of Uncle Tom's Cabin by the Disney characters. The advertising poster for the film shows Mickey with exaggerated, orange lips; bushy, white sidewhiskers.

In the U.S., by the 1950s, the NAACP had begun calling attention to such portrayals of African Americans and mounted a campaign to put an end to blackface performances and depictions. For decades, darky images had been seen in the branding of everyday products and commodities such as Picaninny Freeze, the Coon Chicken Inn[177] restaurant chain, and Nigger Hair Tobacco. With the eventual successes of the modern day Civil rights movement, such blatantly racist branding practices ended in the U.S., and blackface became an American taboo.

Continued use in Asia

[edit]However, blackface-inspired iconography continue in popular media in Asia. In Japan, in the early 1960s, a toy called Dakkochan became hugely popular. Dakkochan was a black child with large red lips and a grass skirt. There were boy and girl dolls, with the girls being distinguished by a bow. The black skin of the dolls was said to have been significant and in-line with the rising popularity of jazz. Novelist Tensei Kawano went as far as to state, "We of the younger generation are outcasts from politics and society. In a way we are like Negroes, who have a long record of oppression and misunderstanding, and we feel akin to them."[178]

Japanese manga and anime continue to prominently feature characters inspired by "darky" iconography, which includes Mr. Popo from the Dragon Ball series and the design of the Pokémon character Jynx. Both Mr. Popo and Jynx have been censored on American broadcasting. An American licensing company, 4 Licensing Company had Dragon Ball Z on their anime block 4Kids. The character Mr. Popo was turned bright blue and given orange-yellow lips[179] In 2011, a television drama in the Philippines titled Nita Negrita was widely criticized in the media and by academics.[180][181]

Prominent brands continue to use the iconography, including Chinese toothpaste brand Darlie, which was changed from "Darkie" and "Black Man" in Thailand.[182] Vaudeville-inspired blackface remains frequently used in commercials.[180]

The Chinese New Year broadcast on China Central Television has drawn international criticism for its use of blackface. In 2018, the show featured a comedy sketch where a Chinese actress wore blackface and padded buttocks.[183] The 2021 show included an "African Song and Dance" routine featuring dancers in traditional Congolese dress and black face paint.[184]

Notable instances outside the United States

[edit]Over time, blackface and "darky" iconography became artistic and stylistic devices associated with Art Deco and the Jazz Age. By the 1950s and 1960s, particularly in Europe, where it was more widely tolerated, blackface became a kind of outré, camp convention in some artistic circles. The Black and White Minstrel Show was a popular British musical variety show that featured blackface performers, and remained on British television until 1978 and in stage shows until 1989. Many of the songs were from the music hall, country and western, and folk traditions.[185] Actors and dancers in blackface appeared in music videos such as Grace Jones's "Slave to the Rhythm" (1985, also part of her touring piece A One Man Show),[186] Culture Club's "Do You Really Want to Hurt Me" (1982)[187] and Taco's "Puttin' On the Ritz" (1983).[188]

When trade and tourism produce a confluence of cultures, bringing differing sensibilities regarding blackface into contact with one another, the results can be jarring. When Japanese toymaker Sanrio Corporation exported a darky-icon character doll (the doll, Bibinba, had fat, pink lips and rings in its ears)[189] in the 1990s, the ensuing controversy prompted Sanrio to halt production.[190]

Trademark for Conguitos, a confection manufactured by the LACASA Group[191] features a tubby, little brown character with full, red lips. It became a topic of controversy after a Manchester City player compared his black teammate to the character.[192] In Britain, "Golly",[193] a golliwog character, fell out of favor in 2001 after almost a century as the trademark of jam producer James Robertson & Sons, but the debate still continues whether the golliwog should be banished in all forms from further commercial production and display, or preserved as a treasured childhood icon. In France, the chocolate powder Banania[194] still uses a face with large red lips derived from the Senegalese Tirailleurs as its emblem. The licorice brand Tabu, popularized by Perfetti in the middle of the 20th century, introduced in the 1980s a cartoon minstrel mascot inspired by Al Jolson's blackface performance in The Jazz Singer, which is still in use today.[195]

The influence of blackface on branding and advertising, as well as on perceptions and portrayals of black people, generally, can be found worldwide.

Australia

[edit]

In October 2009, a talent-search skit on Australian TV's Hey Hey It's Saturday reunion show featured a tribute group for Michael Jackson, the "Jackson Jive", in blackface, with the Michael Jackson character in whiteface. American performer Harry Connick, Jr. was one of the guest judges and objected to the act, stating that he believed it was offensive to black people, and gave the troupe a score of zero. The show and the group later apologised to Connick, with the troupe leader of Indian descent stating that the skit was not intended to be offensive or racist.[196]

In 1999, Sam Newman wore blackface to impersonate legendary Indigenous Australian Football League footballer Nicky Winmar after Winmar did not attend a scheduled appearance on the program.[197]

Belgium and Netherlands

[edit]Christian traditions: Sinterklaas

[edit]

In the Netherlands and Belgium, people annually celebrate St. Nicolas Eve with Sinterklaas, the Dutch version of Saint Nicholas, accompanied by multiple helpers or "Zwarte Pieten" (Black Petes). The first is typically an older white man similar to the American Santa, while the latter are usually adolescent boys and girls, and men and women in make-up and attire similar to the American blackface. The task of the Pieten is generally to entertain the children with jokes and pranks, and to help Sinterklaas distribute presents and dole out candy. The Pieten wear Moorish page boy costumes and partake in parades.[198]

The Moorish Zwarte Piet character has been traced back to the middle of the 19th century when Jan Schenkman, a popular children's book author, added a black servant to the Sinterklaas story.[199] The Dag Sinterklaas TV series written by Hugo Matthysen in Belgium since the early 1990s provided a non-racial explanation: Zwarte Piet is black not because of his skin, because of sliding through the chimney to deliver presents. Twenty years later, Bart Peeters (the main actor in the series) stated it is thanks to Matthysen that in Belgium the Sinterklaas event has not been subject of a racism discussion as it has been in the Netherlands, because the series explains that the figure of Zwarte Piet has nothing to do with slavery.[200] However, the original and archetypal Zwarte Piet is believed to be a continuation of a much older custom in which people with blackface appeared in Winter Solstice rituals.[201] In other parts of Western Europe and in Central Europe, black-faced and masked people also perform the role of companions of Saint Nicholas, who is known as Nikolo in Austria, Nikolaus in Germany and Samichlaus in Switzerland. Also on Saint Martin's Eve, black-faced men go around in processions through Wörgl and the Lower Inn Valley, in Tyrol.[202]

Due to Zwarte Piet's strong aesthetic resemblance to the archetypal US blackface, as well as the dynamics between the blackface servants and the white Sinterklaas,[203] there has been international condemnation of the practice since the 1960s.[204] Some of the stereotypical elements have been toned down in recent decades as a result of increasing protests within the nation.[205] For example, there has been a transition towards applying only a few smears of 'soot' to the Piet's cheeks, rather than apply a full blackface.[206] The public support for changing the character was at 5% (versus 89% opposed to such changes) in 2013,[207] which increased to 26% (versus 68% opposed to such changes) in 2017.[208] However, in 2019, support for changing the character of Zwarte Piet underwent a slight decline, with opposition to changes increasing.[209]

In 2020, following the murder of George Floyd and worldwide protests against racism, the Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte (who since 2013 had strongly supported Zwarte Piet and condemned protests against suggestions for change) stated he had changed his mind on the matter and hoped the tradition would die out. Yet, he emphasized not intending to impose an official ban and noted he too retains sympathy towards those who do not want to let go of Zwarte Piet.[210][211][212]

Canada

[edit]Up until the early 2000s, white comedians sometimes used makeup to represent a black person, most often as a parody of an actual person. Many of these segments have been aired during the annual New Year's Eve TV special Bye Bye. For instance, the 1986 edition[213] features three such skits:

- a multi-ethnic version of the series Le temps d'une paix (fr), in which comedienne Michèle Deslauriers played the character Mémère Bouchard as if she hailed from Africa;

- a reference to a joint concert by Quebec rocker Marjo and U.S. diva Eartha Kitt, in which Deslauriers and comic Dominique Michel alluded to Kitt spilling wine on Marjo during the show's press conference;[214]

- a mock American Express commercial spoofing president Ronald Reagan's foreign policy, in which Deslauriers, Michel and actor Michel Côté played Middle Eastern arms buyers.

The Montreal-based satiric group Rock et Belles Oreilles did its own blackface sketches, for instance when comedian Yves Pelletier disguised himself as comedian and show host Gregory Charles, making fun of his energetic personality (not of his racial background) on his television game show Que le meilleur gagne.[215] RBO also did a parody of a talk show where a stereotypical Haitian man (Pelletier again) was easily offended,[216] as well as a group parody of the Caribbean band La Compagnie Créole[217] and a sketch about the lines of African-American actors that were mangled in movie translations.[218] Pelletier did another parody of Gregory Charles for the New Year's Eve TV special Le Bye Bye de RBO in 2006 (as an homage to Charles who had had a particularly successful year[219]), along with a parody of Governor General Michaëlle Jean.[220] And in RBO's 2007 Bye Bye, Guy A. Lepage impersonated a black Quebecer testifying during the Bouchard-Taylor hearings on cultural differences,[221] while in another sketch, Lepage, Pelletier and Bruno Landry impersonated injured Darfur residents.[222]

In September 2011, HEC Montréal students caused a stir when using blackface to "pay tribute" to Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt during Frosh Week. The story went national, and was even covered on CNN.[223] The university students were filmed in Jamaican flag colours, chanting "smoke weed" in a chorus.[224] The university later apologized for the lack of consciousness of its student body.[225][226]

In May 2013, comedian Mario Jean (fr) took part in the award show Le gala des Olivier, and imitated several fellow comics, donning blackface when he came to Boucar Diouf (fr), a Senegalese-born storyteller.[227][228] Many Quebec pundits defended the practice[229][230][231] and Diouf himself praised Jean for his open-mindedness.[232]

In December 2013, white actor Joel Legendre (fr) performed in blackface in Bye Bye 2013, as part of yet another parody[233] of Gregory Charles, this time as host of the variety show Le choc des générations.

In December 2014, the satirical end-of-year production by Théâtre du Rideau Vert, a mainstream theatre company, included a blackface representation of hockey player P.K. Subban by actor Marc Saint-Martin.[234] Despite some criticism the sketch was not withdrawn.[235]

In March 2018, comedian of the year[236] Mariana Mazza (fr), whose parents are Arab and Uruguayan, celebrated International Women's Day by putting up a post on her Facebook page which read "Vive la diversité" (Hurray for diversity) and was accompanied by a picture of herself surrounded by eight ethnic variations, including one in a wig and makeup that showed what she'd look like if she were black.[237][238] She immediately received a flurry of hate messages and death threats, and two days later, posted another message[239] in which she apologized to whoever had been offended, adding that she had been "naively" trying to "express her support for all these communities".

In June 2018, theatre director Robert Lepage was accused of staging scenes that were reminiscent of blackface[240] when he put together the show SLĀV at the Montreal Jazz Festival, notably because white performers were dressed as slaves as they picked cotton.[241] After two initial performances, lead singer Betty Bonifassi broke an ankle and the rest of the summer run was canceled, but later performances were nevertheless scheduled in other venues.[242] The controversy prompted further protests about the play Kanata that Lepage was to stage in Paris about the Canadian Indian residential school system – without resorting to any indigenous actors.[243] The project was briefly put on hold when investors pulled out, but the production eventually resumed as planned.[244]

In 2022, Netflix pulled episode 2 of the popular TV series Les filles de Caleb (which takes place in the 19th century), because the main character, played by Roy Dupuis, dons blackface makeup in order to act as magus Balthazar in a school Nativity play.[245]

Justin Trudeau blackface controversy

[edit]In 2019, Time published a photograph of the Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, wearing brownface makeup in the spring of 2001.[246] The photograph, which had not been previously reported, was taken at an "Arabian Nights"-themed gala. The photograph showed Trudeau, wearing a turban and robes with his face, neck and hands completely darkened. The photograph appeared in the 2000–2001 yearbook of the West Point Grey Academy, where Trudeau was a teacher. A copy of the yearbook was obtained by Time earlier in the month from Vancouver businessman Michael Adamson, who was part of the West Point Grey Academy community. Adamson said that he first saw the photograph in July and felt it should be made public. On September 19, 2019, Global News obtained and published a video from the early 1990s showing Trudeau in blackface.[247] The video showed Trudeau covered in dark makeup and raising his hands in the air while laughing, sticking his tongue out and making faces. The video showed his arms and legs covered in makeup as well as a banana in his pants, eliciting strong negative reactions.[248] Trudeau admitted that he could not recall how many times he wore blackface after additional footage surfaced.[249]

China

[edit]In May 2016, a global controversy broke regarding a television commercial for Qiaobi clothes washing fluid. The commercial showed a pouch of cleaning liquid being forced into a black man's mouth before he is pushed into a washing machine. He emerges later as an Asian man.[250]

On February 15, 2018, a comedy sketch titled "Same Joy, Same Happiness" intending to celebrate Chinese-African ties on the CCTV New Year's Gala, which draws an audience of up to 800 million, showed a Chinese actress in blackface makeup with a giant fake bottom playing an African mother, while a performer only exposing black arms playing a monkey accompanied her. At the end of the skit, the actress shouted, "I love Chinese people! I love China!" After being broadcast, the scene was widely criticized as being "disgusting", "awkward" and "completely racist" on Twitter and Sina Weibo.[251][252] According to the street interviews by the Associated Press in Beijing on February 16, some Chinese people believed this kind of criticism was overblown.[253] Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang, who also watched the skit, said that China had consistently opposed any form of racism, and added, "I want to say that if there are people who want to seize on an incident to exaggerate matters, and sow discord in China's relations with African countries, this is a doomed futile effort" at a daily news briefing on February 22, 2018.[254]

In 2021 CCTV's New Year's Gala show once again featured performers in blackface wearing approximations of African clothing. Like in 2018 it received criticism both within China and internationally. The Chinese foreign ministry responded to criticism by saying that it was not an issue and that anyone saying otherwise must have ulterior motives.[255]

Colombia

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2022) |

The television comedy Sábados Felices included a blackface character, who after a controversy changed his makeup to look like a camouflaged soldier.[256][257]

Ecuador

[edit]

In Ecuador, there's a traditional festival held in Latacunga called "La Mama Negra" also known as La Santísima Tragedia in which a man in blackface makeup portrays a black woman liberated from slavery holding her youngest child.[258]

Finland

[edit]In Finland, a version of the Star boys' singing procession originating in the city of Oulu, a musical play known as Tiernapojat, has become established as a cherished Christmas tradition nationwide. The Tiernapojat show is a staple of Christmas festivities in schools, kindergartens, and elsewhere, and it is broadcast every Christmas on radio and television. The Finnish version contains non-biblical elements such as King Herod vanquishing the "king of the Moors", whose face in the play has traditionally been painted black. The character's color of skin is also a theme in the procession's lyrics.[259]

The last installation of the Pekka and Pätkä comedy film series, Pekka ja Pätkä neekereinä (Pekka and Pätkä as Negroes), was made in 1960. In the film a computer tells the title characters that a "negro" would be a suitable profession for them. They blacken their faces and pretend to be American or African entertainers performing in a night club, talking self-invented gibberish that is supposed to be English. The computer meant "negro" as a now archaic term for a journalist, which originates from journalists' hands becoming tinted black with ink when handling prints.[260][261] When Finland's national public broadcasting company Yle aired this film 2016, some people on the social media disapproved of it and insisted that the film should have been censored, or at least the name changed. A representative from Yle said that an old movie should be evaluated in the context of its own time, and that the idea of the movie is to laugh at people being prejudiced. When the film series was aired in 2019, this particular film of the series was left unaired.[262][263]

Before the 1990s the word "neekeri" (negro) was generally considered a neutral, inoffensive word.[264]

Germany

[edit]Examples of theatrical productions include the many productions of the play Unschuld ("Innocence") by the German writer Dea Loher. The play features two black African immigrants, but the use of black-face is not part of the stage directions or instructions.[265] The staging of the play at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin in 2012 was subject of protest.[266] The activist group "Bühnenwatch" (stage watch) performed a stunt in one of the stagings: 42 activists, posing as spectators, left the audience without a word and later distributed leaflets to the audience. Fundamental of the criticism was that the use of black-face solidifies stereotypes regardless of any good intentions and supports racist structures. The critics were invited to a discussion with the director, actors, theatre manager and other artists of the Deutsches Theater. As a result of the discussion, Deutsches Theater changed the design of actor make-up. Ulrich Khuon, the theatre manager, later admitted to being surprised by the protest and is now in a process of reflection.[267]

German productions of Herb Gardner's I'm Not Rappaport almost always cast the role of Midge Carter, the black character, famously portrayed in the U.S. by Ossie Davis, with a white actor in black makeup. The 2012 production of the play at the Berlin Schlosspark-Theater was the subject of protest.[268][269] The director, Thomas Schendel, in his response to critics, argued that the classical and common plays would not offer enough roles that would justify a repertoire position for a black actor in a German theatre company. The protest grew considerably and was followed by media reports. While advocates of the theatre indicated that in principle it should be possible for any actor to play any character and that the play itself has an anti-racist message, the critics noted that the letter unwittingly disclosed the general, unexpressed policy of German theatres, i.e., that white actors are accounted to be qualified for all roles, even black ones, while black actors are suitable only for black roles.[270] Other authors said that this problem in Germany generally exists for citizens with an immigrant background.[271][272] The debate also received foreign media attention. The Schlosspark-Theater announced plans to continue the performances, and the German publishing company of Rappaport stated it will continue to grant permits for such performances.

German dramatists commented on the debate:

Unfortunately, I do not believe that our society has come to accept a black Faust in the theatre.

— Christian Tombeil, theater manager of Schauspiel Essen, 2012[273]

We too have a problem to deal with issues of racism. We try to work it out by promoting tolerance, but tolerance is not a solution to racism. Why not? Because it does not matter whether our best friends are immigrants if, at the same time, we cannot cast a Black man for the part of Hamlet because then nobody could truly understand the "real" essence of that part. Issues of racism are primarily issues of representation, especially in the theatre.

— René Pollesch, director, 2012[274]

In 2012, the American dramatist Bruce Norris cancelled a German production of his play Clybourne Park when it was disclosed that a white actress would portray the African-American "Francine". A subsequent production using black German actors was successfully staged.[275]

Guatemala

[edit]Guatemalan 2015 elected president, Jimmy Morales, was a comic actor. One of the characters he impersonated in his comic show "Moralejas" was called Black Pitaya which used blackface makeup. Jimmy Morales defended his blackface character saying he is adored by the country's black Garifuna and indigenous Mayan communities.[276]

Iran

[edit]

Hajji Firuz is a character in Iranian folklore who appears in the streets by the beginning of the New Year festival of Nowruz.[277] Additionally there is Siah-Bazi, a type of Persian theatre in Iran that involves a blackfaced character.[278][279]

Japan

[edit]In Japanese hip hop, a subculture of hip-hoppers subscribe to the burapan style, and are referred to as blackfacers.[280] The appearance of these blackfacers is evidence of the popularity of the hip-hop movement in Japan despite what is described as racist tendencies in the culture.[281] It was reported in 2006 that some Japanese hip-hop fans found it embarrassing and ridiculous for fans to change their appearance with blackface in attempt to embrace the culture. In some instances it could be seen as a racist act, but for many of the young Japanese fans it was seen as an appropriate way of immersing in the hip hop culture.[282] The use of blackface is seen by some as a way to rebel against the culture of surface images in Japan.[283]

Blackface has also been a contentious issue in the music scene outside of hip hop.[284] One Japanese R&B group, the Gosperats, has been known to wear blackface makeup during performances.[285] In March 2015 a music television program produced by the Fuji TV network was scheduled to show a segment featuring two Japanese groups performing together in blackface, Rats & Star and Momoiro Clover Z. A picture was published online by one of the Rats & Star members after the segment was recorded, which led to a campaign against broadcasting of the segment. The program that aired on March 7 was edited by the network to remove the segment "after considering the overall circumstances",[286] but the announcement did not acknowledge the campaign against the segment.[287]

Mexico

[edit]In modern-day Mexico there are examples of images (usually caricatures) in blackface (e.g., Memín Pinguín). Though there is backlash from international communities, Mexican society has not protested to have these images changed to racially sensitive images. On the contrary, in the controversial Memín Pinguín cartoon there has been support publicly and politically, such as from the Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs Luis Ernesto Derbez.[288] Currently in Mexico only 3–4% of the population are Afro-Mexicans (this percentage includes Asian Mexicans).

Panama

[edit]Portobelo's Carnival and Congo dance in Panama include a use of blackface as a form of celebration of African history, an emancipatory symbol. Black men paint their faces with charcoal which represents three things. Firstly, the blackface is used as a tool to remember their African ancestors. Secondly, the black face is representative of the disguise or concealment on the run which slaves would have used to evade the Spanish colonizers. Lastly, the practice of blackface is used as a way to signify the code or "secret language" which slaves would have used during the time of the Spanish occupation. During the celebration, for example, good morning will mean good night, and wearing black, or in this case wearing blackface, which normally denotes a time of mourning, is instead used as a way to represent a time of celebration.[289]

Portugal and Brazil

[edit]Use of black performance in impersonations was quite frequently used in the impressions show A Tua Cara não Me É Estranha, with blackface impressions of Michael Jackson,[290][291] Siedah Garrett,[292] Tracy Chapman,[293] Louie Armstrong,[294] Nat King Cole,[295] among others. In 2018, Eduardo Madeira dressed up as Serena Williams,[296] adding an African accent the tennis player does not have in real life.

In Brazil, there has been at least some history of non-comedic use of blackface, using white actors for black characters like Uncle Tom (although the practice of "racelift", or making black/mulatto characters into mestiços/swarthy whites/caboclos, is more frequent than blackface).[297][298][299] Use of blackface in humor has been used more rarely than in Portugal, although it also continues into this century (but it creates major uproar among the sizeable and more politically active Afro-Brazilian community).[300]

Russia

[edit]Soviet Russian writers and illustrators sometimes inadvertently perpetuated stereotypes about other nations that are now viewed as harmful. For example, a Soviet children's book or cartoon might innocently contain a representation of black people that would be perceived as unquestionably offensive by the modern-day western standards, such as bright red lips and other exaggerated features, similar to the portrayal of blacks in American minstrel shows. Soviet artists "did not quite understand the harm of representing black people in this way, and continued to employ this method, even in creative productions aimed specifically at critiquing American race relations".[301]