Billy Joel

Billy Joel | |

|---|---|

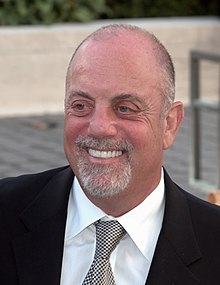

Joel in 2009 | |

| Born | William Martin Joel May 9, 1949 New York City, U.S. |

| Other names | The Piano Man |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1964–present |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3, including Alexa Ray |

| Relatives |

|

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Hicksville, New York, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Member of | Billy Joel Band |

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | billyjoel |

| Signature | |

| |

William Martin Joel (born May 9, 1949) is an American singer, songwriter and pianist. Nicknamed the "Piano Man" after his signature 1973 song of the same name,[4][5] Joel has had a successful career as a solo artist since the 1970s. From 1971 to 1993, he released 12 studio albums spanning the genres of pop and rock, and in 2001 released a one-off studio album of classical compositions. Joel is one of the world's best-selling music artists[6] and the fourth-best-selling solo artist in the United States,[7] with over 160 million records sold worldwide. His 1985 compilation album, Greatest Hits – Volume I & Volume II, is one of the best-selling albums in the United States.[8]

Joel was born in the Bronx in New York City and grew up on Long Island, where he began taking piano lessons at his mother's insistence. After dropping out of high school to pursue a music career, Joel took part in two short-lived bands, The Hassles and Attila, before signing a record deal with Family Productions and embarking on a solo career with his debut album, Cold Spring Harbor (1971). In 1972, Joel caught the attention of Columbia Records after a live radio performance of "Captain Jack" became popular in Philadelphia, prompting him to sign a new record deal with the company, through which he released his second album, Piano Man (1973). After Streetlife Serenade (1974) and Turnstiles (1976), Joel achieved his critical and commercial breakthrough with The Stranger (1977). It became Columbia's best-selling release, selling over 10 million copies and spawning the hit singles "Just the Way You Are", "Movin' Out (Anthony's Song)", "Only the Good Die Young", and "She's Always a Woman", as well as the concert staples "Scenes from an Italian Restaurant" and "Vienna".

52nd Street (1978) was Joel's first album to peak at No. 1 on the Billboard 200. Glass Houses (1980) was an attempt to further establish himself as a rock artist; it featured "It's Still Rock and Roll to Me" (Joel's first single to top the Billboard Hot 100), "You May Be Right", "Don't Ask Me Why", and "Sometimes a Fantasy". The Nylon Curtain (1982) stemmed from a desire to create more lyrically and melodically ambitious music. An Innocent Man (1983) served as an homage to genres of music that Joel had grown up with in the 1950s, such as rhythm and blues and doo-wop; it featured "Tell Her About It", "Uptown Girl", and "The Longest Time", three of his best-known songs. After River of Dreams (1993), he largely retired from producing studio material, although he went on to release Fantasies & Delusions (2001), featuring classical compositions composed by him and performed by British-Korean pianist Richard Hyung-ki Joo. Joel provided voiceover work in 1988 for the Disney animated film Oliver & Company, performing the song "Why Should I Worry?", and contributed to the soundtracks to several films, including Easy Money (1983), Ruthless People (1986), and Honeymoon in Vegas (1992). Joel returned to composing new music with the 2024 single “Turn the Lights Back On”.

Joel has had a successful touring career, holding live performances across the globe. In 1987, he became one of the first artists to hold a rock tour in the Soviet Union following the country's alleviation of its ban on rock music. Joel has produced 33 self-written Top 40 hits in the U.S.,[9] three of which ("It's Still Rock and Roll to Me", "Tell Her About It", and "We Didn't Start the Fire") topped the Billboard Hot 100. Joel has been nominated for 23 Grammy Awards, winning 6, including Album of the Year for 52nd Street. Joel was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1992, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1999[10] and the Long Island Music Hall of Fame in 2006. He received the 2001 Johnny Mercer Award from the Songwriters Hall of Fame[11] and was recognized at the 2013 Kennedy Center Honors.[12]

Early life, family and education

[edit]Billy Joel was born on May 9, 1949, in The Bronx. When he was a year old, his family moved to Hicksville, New York in the town of Oyster Bay on Long Island. He and his cousin Judy, whom his parents adopted,[13] were raised in a section of Levitt homes.[14]

His mother, Rosalind (1922–2014),[15] was born in Brooklyn to Jewish parents, Philip and Rebecca Nyman, who emigrated from England.[16] Billy's father, Howard (born Helmut) Joel (1923–2011), a classical pianist[17][14] and businessman, was born in Nuremberg, Germany[14] to a Jewish family, the son of merchant and manufacturer Karl Amson Joel, and educated in Switzerland. Billy's father had created a highly successful mail-order textile business, Joel Macht Fabrik. Escaping the Nazi regime, Howard and his family emigrated to Switzerland. Billy's father sold his business at a fraction of its value in order to emigrate. The family reached the United States via Cuba, because immigration quotas for German Jews prevented direct immigration at the time.[14] In the United States, Howard became an engineer but always loved music.

Billy Joel's parents met in the late 1930s at City College of New York at a Gilbert and Sullivan performance.[17] He has said that neither of his parents talked much about World War II, which were such dark years; it was not until later that Joel learned more about his father's family. After Rosalind and Howard Joel divorced in 1957, Howard returned to Europe, as he had never liked the US; he considered the people uneducated and materialistic.[14] He settled in Vienna, Austria, and later remarried. Joel has a half-brother, Alexander Joel, born to his father in Europe, who became a classical conductor there and was the chief musical director of the Staatstheater Braunschweig from 2001 to 2014.[18][19]

Joel reluctantly began taking piano lessons at age four at his mother's insistence.[17] His teachers included the noted American pianist Morton Estrin[20] and musician Timothy Ford. Joel says that he is a better organist than a pianist.[21] As a teenager, Joel took up boxing so he could defend himself.[22] He boxed successfully on the amateur Golden Gloves circuit for a short time, winning 22 bouts, but abandoned the sport shortly after his nose was broken in his 24th match.[23]

Although Joel's parents were Jewish, he did not grow up in the religion. "I was not brought up Jewish in any religious way. My circumcision was as Jewish as they got."[24] He attended a Roman Catholic church with friends. At age 11, he was baptized in a Church of Christ in Hicksville. He now identifies as an atheist Jew.[25][26][27][28][29]

Joel attended Hicksville High School in Hicksville until 1967 but did not graduate with his class.[17] He was playing at a piano bar to help support himself, his mother and sister, and missed a crucial English exam after playing a late-night gig the evening before.[17] Although Joel was a comparatively strong student, at the end of his senior year, he did not have enough credits to graduate. Rather than attend summer school to earn his diploma, Joel decided to begin a music career: "I told them, 'To hell with it. If I'm not going to Columbia University, I'm going to Columbia Records, and you don't need a high school diploma over there'."[30] In 1992, he submitted essays to the school board in lieu of the missed exam. They were accepted, and he was awarded his diploma at Hicksville High's annual graduation ceremony 25 years after leaving.[31]

Music career

[edit]1964–1970: Early career

[edit]Influenced by early rock & roll and rhythm & blues artists, including Elvis Presley and The Everly Brothers, Joel favored tightly structured pop melodies and down-to-earth songwriting.[32] After seeing The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, Joel decided to pursue a career in music. He recalled:[33]

That one performance changed my life ... Up to that moment I'd never considered playing rock as a career... (W)hen I saw four guys who didn't look like they'd come out of the Hollywood star mill, who played their own songs and instruments, and especially because you could see this look in John Lennon's face—and he looked like he was always saying: '--- you!'—I said: 'I know these guys, I can relate to these guys, I am these guys. This is what I'm going to do—play in a rock band'.

At age 16, Joel joined the Echoes,[34] a group which specialized in British Invasion covers. The Echoes began recording in 1965. Joel played piano on several records released through Kama Sutra Productions and on recordings produced by Shadow Morton. Joel played on a demo version of "Leader of the Pack", which became a major hit for the Shangri-Las.[35] Joel states that in 1964 he played on a recording of the Shangri-Las' "Remember (Walking in the Sand)" but he is unaware of whether he played on the demo or master version.[36] The released single included a co-producer credit for Artie Ripp,[37] who later was the first to sign and produce Joel as a solo artist after Michael Lang, who had given Joel a monetary advance, passed Joel along to Ripp to focus his attentions elsewhere.[38]

In late 1965, the Echoes changed their name to the Emeralds, and then to the Lost Souls. Joel left the band in 1967 to join the Hassles, a Long Island group that had signed with United Artists Records.[32] Over the next year and a half, they released four singles and two albums (The Hassles and Hour of the Wolf). All were commercial failures. Joel and drummer Jon Small left the Hassles in 1969 to form the duo Attila, releasing an eponymous debut album in July 1970. The duo disbanded the following October when Joel began an affair with Small's wife, Elizabeth. The pair later married.[39]

1970–1974: Cold Spring Harbor and Piano Man

[edit]

Joel signed a contract with the record company Family Productions,[17][40] with which he recorded his first solo album, Cold Spring Harbor, named for a hamlet on his native Long Island. Ripp states that he spent US$450,000 developing Joel;[40] nevertheless, the album was mastered at too high a speed and was a technical and commercial disappointment.[41]

The popular songs "She's Got a Way" and "Everybody Loves You Now" were originally released on this album, but went largely unnoticed until being released as live performances on Songs in the Attic (1981). Columbia released a remastered version of Cold Spring Harbor in 1983, with certain songs shortened or re-orchestrated.[41]

Joel began his Cold Spring Harbor tour in the fall of 1971, touring with his band, consisting of Rhys Clark on drums, Al Hertzberg on guitar, and Larry Russell on bass guitar, throughout the mainland United States and Puerto Rico, opening for such artists as the J. Geils Band, The Beach Boys, Badfinger and Taj Mahal. Joel's performance at the Puerto Rican Mar y Sol Pop Festival was especially well-received; and although recorded, Joel refused to have it published on the Mar Y Sol compilation album Mar Y Sol: The First International Puerto Rico Pop Festival. Nevertheless, interest in his music grew.[42]

During the spring of 1972, the Philadelphia radio station WMMR-FM began playing a concert recording of "Captain Jack", which became an underground hit on the East Coast. Herb Gordon, a Columbia Records executive, heard Joel's music and introduced him to the company. Joel signed a recording contract with Columbia in 1972 and moved to Los Angeles; he lived there for the next three years.[1][18] For six months he worked at The Executive Room piano bar on Wilshire Boulevard as "Bill Martin".[17] During that time, he composed his signature song "Piano Man" about the bar's patrons.[43]

Despite Joel's new contract, he was legally bound to Family Productions. Artie Ripp sold Joel's first contract to Columbia. Walter Yetnikoff, the president of CBS/Columbia Records at the time, bought back the rights to Joel's songs in the late 1970s, giving the rights to Joel as a birthday gift.[44][45] Yetnikoff notes in the documentary The Last Play at Shea that he had to threaten Ripp to close the deal.

Joel's first album with Columbia was Piano Man (1973). Despite modest sales, the album's title track became his signature song, ending nearly every concert. That year Joel's touring band changed. Guitarist Al Hertzberg was replaced by Don Evans, and bassist Larry Russell by Patrick McDonald, himself replaced in late 1974 by Doug Stegmeyer, who stayed with Joel until 1989. Rhys Clark returned as drummer and Tom Whitehorse as banjoist and pedal steel player; Johnny Almond joined as saxophonist and keyboardist. The band toured the U.S. and Canada extensively, appearing on popular music shows. Joel's songwriting began attracting more attention; in 1974 Helen Reddy recorded the Piano Man track "You're My Home".

1974–1977: Streetlife Serenade and Turnstiles

[edit]In 1974, Joel recorded his second Columbia album in Los Angeles, Streetlife Serenade. His manager at the time was Jon Troy, an old friend from New York's Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood; Troy was soon replaced by Joel's wife Elizabeth.[46] Streetlife Serenade contains references to suburbia and the inner city. It is perhaps best known for "The Entertainer", a No. 34 hit in the U.S. Upset that "Piano Man" had been significantly cut for radio play, Joel wrote "The Entertainer" as a sarcastic response: "If you're gonna have a hit, you gotta make it fit, so they cut it down to 3:05." Although Streetlife Serenade was viewed unfavorably by critics,[47][48] it contains the notable songs "Los Angelenos" and "Root Beer Rag", an instrumental that was a staple of his live set in the 1970s.

In late 1975, Joel played piano and organ on several tracks on Bo Diddley's The 20th Anniversary of Rock 'n' Roll all-star album.

Disenchanted with Los Angeles, Joel returned to New York City in 1975 and recorded Turnstiles, the first album he recorded with the musicians with whom he toured. Produced by James William Guercio (then Chicago's producer), Turnstiles was first recorded at Caribou Ranch with members of Elton John's band. Dissatisfied with the result, Joel re-recorded the songs and produced the album himself.

"Say Goodbye to Hollywood" was a minor hit, covered by Ronnie Spector and Nigel Olsson. In a 2008 radio interview, Joel said that he no longer performs the song because singing it in its high original key "shreds" his vocal cords; however, he did finally play it live for the first time since 1982 when he sang it at the Hollywood Bowl in May 2014. Although never released as a single, "New York State of Mind" became one of Joel's best-known songs; Barbra Streisand recorded a cover and Tony Bennett performed it as a duet with Joel on Playing with My Friends: Bennett Sings the Blues. Other notable songs from the album include "Summer, Highland Falls"; "Miami 2017 (Seen the Lights Go Out on Broadway)" and "Prelude/Angry Young Man", a concert mainstay.

1977–1979: The Stranger and 52nd Street

[edit]Columbia Records introduced Joel to Phil Ramone, who produced all of Joel's studio albums from 1977 to 1986. The Stranger (1977) was an enormous commercial success, yielding four Top-25 hits on the Billboard charts: "Just the Way You Are" (No. 3), "Movin' Out" (No. 17), "Only the Good Die Young" (No. 24) and "She's Always a Woman" (No. 17). Joel's first Top Ten album, The Stranger reached number two on the charts and was certified multi-platinum, besting Simon & Garfunkel's Bridge over Troubled Water[49] as Columbia's previous bestselling album. "Just the Way You Are"—written for Joel's first wife, Elizabeth Weber[50]—was inspired by a dream[51] and won Grammy awards for Record of the Year and Song of the Year.[52] On tour in Paris, Joel learned the news late one night in a hotel room.[34] It also featured "Scenes from an Italian Restaurant", an album-oriented rock classic, which has become one of his best-known songs. It is one of Joel's favorite of his own songs, which has become a firm staple of his live shows,[53] and "Vienna", also one of Joel's personal favorites[54][55] and as of 2022 one of his most streamed songs on the internet.[56] Rolling Stone later ranked The Stranger the 70th greatest album of all time.[57]

Joel released 52nd Street in 1978, naming it after Manhattan's 52nd Street, which, at the time of its release, served as the world headquarters of CBS/ Columbia. The album sold over seven million copies, propelled to number one on the charts by the hits "My Life" (No. 3), "Big Shot" (No. 14) and "Honesty" (No. 24). A cover of "My Life" by Gary Bennett became the theme for the television sitcom Bosom Buddies. 52nd Street also won Grammy awards for Best Pop Vocal Performance, Male and Album of the Year.

In 1979, Joel traveled to Havana, Cuba to participate in the historic Havana Jam festival March 2–4, alongside Rita Coolidge, Kris Kristofferson, Stephen Stills, the CBS Jazz All-Stars, the Trio of Doom, Fania All-Stars, Billy Swan, Bonnie Bramlett, Mike Finnegan, Weather Report, and an array of Cuban artists including Irakere, Pacho Alonso, Tata Güines and Orquesta Aragón.[58] His performance is captured in Ernesto Juan Castellanos's documentary Havana Jam '79.

52nd Street was the first commercially released album on the then-new compact disc format, in 1982.[59]

1979–1983: Glass Houses and The Nylon Curtain

[edit]The success of his piano-driven ballads like "Just the Way You Are", "She's Always a Woman" and "Honesty" led some critics to label Joel a "balladeer" and "soft rocker". He thought these labels were unfair and insulting, and with Glass Houses, Joel tried to record an album that proved that he could rock harder than his critics gave him credit for, occasionally imitating and referring to the style of new wave rock music that was starting to become popular. On the album cover, Joel is pictured in a leather jacket, about to throw a rock at a glass house (referring to the adage that "people who live in glass houses shouldn't throw stones").

Glass Houses spent six weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard chart and yielded the hits "You May Be Right" (No. 7, May 1980), "It's Still Rock and Roll to Me", (No. 1, July 1980), "Don't Ask Me Why" (No. 19, September 1980) and "Sometimes a Fantasy" (No. 36, November 1980). "It's Still Rock and Roll to Me", Joel's first Billboard number-one single, spent 11 weeks in the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 and was the seventh biggest hit of 1980 according to American Top 40. His five sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden in 1980 earned him the Garden's Gold Ticket Award for selling more than 100,000 tickets at the venue.[60][61]

Glass Houses won the Grammy for Best Rock Vocal Performance, Male. It also won the American Music Award for Favorite Album, Pop/Rock category. The album's closing song, "Through The Long Night" (B-side of the "It's Still Rock & Roll to Me" single), was a lullaby that featured Joel harmonizing with himself in a song he says was inspired by The Beatles' "Yes It Is".[42] In a recorded Masterclass at the University of Pennsylvania, Joel recalled that he had written to the Beatles asking them how to get started in the music industry. In response, he received a pamphlet about Beatles merchandise. This later led to the idea of Joel conducting Q&A sessions around the world answering questions that people had about the music industry.[62]

Joel's next release, Songs in the Attic, was composed of live performances of lesser-known songs from the beginning of his career. It was recorded at larger US arenas and in intimate night club shows in June and July 1980. This release introduced many fans, who discovered Joel when The Stranger became a smash in 1977, to many of his earlier compositions. The album reached No. 8 on the Billboard chart and produced two hit singles: "Say Goodbye to Hollywood" (No. 17), and "She's Got a Way" (No. 23). It sold over 3 million copies. Although not as successful as some of his previous albums, it was still considered a success by Joel.[42]

The next wave of Joel's career commenced with the recording of The Nylon Curtain. With it, Joel became more ambitious with his songwriting, which included highly topical songs like "Allentown" and "Goodnight Saigon". Joel has stated that he wanted the album to communicate his feelings about the American Dream and how changes in American politics during the Reagan administration meant that "all of a sudden you weren't going to be able to inherit [the kind of life] your old man had."[63] He also tried to be more ambitious in his use of the recording studio. Joel said that he wanted to "create a sonic masterpiece" on The Nylon Curtain. So he spent more time in the studio, crafting the sound of the album, than he had on any previous album.[63] Production of The Nylon Curtain began in the fall of 1981. However, production was temporarily delayed when Joel was involved in a serious motorcycle accident on Long Island on April 15, 1982, severely injuring his hands. Still, Joel quickly recovered from his injuries, and the album ended up being delayed by only a few months.[64]

In 1982, Joel embarked on a brief tour in support of the album. From one of the final shows of the tour, Joel made his first video special, Live from Long Island, which was recorded at the Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Uniondale, New York on December 29, 1982. It was originally broadcast on HBO in 1983 before it became available on VHS.

The Nylon Curtain went to No. 7 on the charts, partially due to heavy airplay on MTV for the videos to the singles "Allentown" and "Pressure", both directed by Russell Mulcahy.

1983–1988: An Innocent Man and The Bridge

[edit]Joel's next album moved away from the serious themes of The Nylon Curtain and struck a much lighter tone. An Innocent Man was Joel's tribute to R&B and doo wop music of the 1950s and 1960s and resulted in Joel's second Billboard number-one hit, "Tell Her About It", which was the first single off the album in the summer of 1983. The album itself reached No. 4 on the charts and No. 2 in UK. It also boasted six top-30 singles, the most of any album in Joel's catalog. The album was well received by critics, with Stephen Thomas Erlewine, senior editor for AllMusic, describing Joel as being "in top form as a craftsman throughout the record, effortlessly spinning out infectious, memorable melodies in a variety of styles."[65]

At the time that the album was released, WCBS-FM began playing "Uptown Girl" both in regular rotation and on the Doo Wop Live.[66][67] The song became a worldwide hit upon its release. The music video of the song, originally written about then-girlfriend Elle MacPherson, featured Christie Brinkley as a high-society girl who pulls her car into the gas station where Joel's character is working. At the end of the video, Joel's "grease monkey" character drives off with his "uptown girl" on the back of a motorcycle. When Brinkley went to visit Joel after being asked to star in the video, the first thing Joel said to her upon opening his door was "I don't dance". Brinkley had to walk him through the basic steps he does in the video. Their work together on this video shoot sparked a relationship between the two which led to their marriage in 1985.[68]

In December, the title song was released as a single and it peaked at No. 10 in the U.S. and No. 8 in the UK, early in 1984. That March, "The Longest Time" was released as a single, peaking at No. 14 on the Hot 100 and No. 1 on the Adult Contemporary chart. That summer, "Leave a Tender Moment Alone" was released and it hit No. 27 while "Keeping the Faith" peaked at No. 18 in January 1985. In the video for "Keeping the Faith", Brinkley also plays the "redhead girl in a Chevrolet". An Innocent Man was also nominated for the Album of the Year Grammy, but lost to Michael Jackson's Thriller.

Joel participated in the USA for Africa "We Are the World" project in 1985.

Following An Innocent Man, Joel was asked about releasing an album of his most successful singles. This was not the first time this topic had come up, but Joel had initially considered "Greatest Hits" albums as marking the end of one's career. This time he agreed, and Greatest Hits Vol. 1 and 2 was released as a four-sided album and two-CD set, with the songs in the order in which they were released. The new songs "You're Only Human (Second Wind)" and "The Night Is Still Young" were recorded and released as singles to support the album; both reached the top 40, peaking at No. 9 and No. 34, respectively. Greatest Hits was highly successful and it has since been certified double diamond by the RIAA, with over 11.5 million copies (23 million units) sold. It is one of the best-selling albums in American music history, according to the RIAA.

Coinciding with the Greatest Hits album release, Joel released a two-volume Video Album that was a compilation of the promotional videos he had recorded from 1977 to that time. Along with videos for the new singles off the Greatest Hits album, Joel also recorded a video for his first hit, "Piano Man", for this project.

Joel's next album, The Bridge (1986), did not achieve the level of success of his previous albums, but it yielded the hits "A Matter of Trust" and "Modern Woman" (both No. 10) from the film Ruthless People, a dark comedy from the directors of Airplane!. The ballad "This is the Time" also charted, peaking at No. 18. On November 18, 1986, an extended version of "Big Man on Mulberry Street" was used on a Season 3 episode of Moonlighting.The Bridge was Joel's last album to carry the Family Productions logo, after which he severed his ties with Artie Ripp. Joel has also stated in many interviews, most recently in a 2008 interview in Performing Songwriter magazine, that he does not think The Bridge is a good album.

In October 1986, Joel and his team started planning a trip to the Soviet Union.[69] There were live performances at indoor arenas in Moscow, Leningrad and Tbilisi. Joel, his family (including young daughter Alexa), and his full touring band made the trip in July 1987.[70] The entourage was filmed for television and video to offset the cost of the trip, and the concerts were simulcast on radio around the world. Joel's Russian tour was the first live rock radio broadcast in Soviet history.[71] The tour was later cited frequently as one of the first fully staged pop rock shows to come to the Soviet Union, although in reality other artists had previously toured in the country, including Elton John, James Taylor and Bonnie Raitt.[72]

Most of that audience took a long while to warm up to Joel's energetic show, something that had never happened in other countries he had performed in. According to Joel, each time the fans were hit with the bright lights, anybody who seemed to be enjoying themselves froze. In addition, people who were "overreacting" were removed by security.[73] During this concert Joel, enraged by the bright lights, flipped his electric piano and snapped a microphone stand while continuing to sing.[74][70] He later apologized for the incident.[70]

The album КОНЦЕРТ (Russian for "Concert") was released in October 1987. Singer Pete Hewlett was brought in to hit the high notes on his most vocally challenging songs, like "An Innocent Man". Joel also did versions of The Beatles' classic "Back in the U.S.S.R." and Bob Dylan's "The Times They Are a-Changin". It has been estimated that Joel lost more than US$1 million of his own money on the trip and concerts, but he has said the goodwill he was shown there was well worth it.[42]

1988–1993: Storm Front and River of Dreams

[edit]The animated film Oliver & Company (1988) features Joel in a rare voice acting role as Dodger, a sarcastic Jack Russell based on Dickens's Artful Dodger. The character's design is based on Joel's image at the time, including his trademark Wayfarer sunglasses. Joel also sang his character's song "Why Should I Worry?".

The recording of Storm Front, which commenced in 1988, coincided with major changes in Joel's career and inaugurated a period of serious upheaval in his business affairs. In August 1989, just before the album was released, Joel dismissed his manager (and former brother-in-law) Frank Weber after an audit revealed major discrepancies in Weber's accounting. Joel subsequently sued Weber for US$90 million, claiming fraud and breach of fiduciary duty, and in January 1990, Joel was awarded US$2 million in a partial judgment against Weber; in April, the court dismissed a US$30 million countersuit filed by Weber.[75]

The first single for the album, "We Didn't Start the Fire", was released in September 1989 and it became Joel's third—and most recent—US number-one hit, spending two weeks at the top. Storm Front was released in October, and it eventually became Joel's first number-one album since Glass Houses, nine years earlier. Storm Front was Joel's first album since Turnstiles to be recorded without Phil Ramone as producer. For this album, he wanted a new sound, and worked with Mick Jones of Foreigner. Joel is also credited as one of the keyboard players on Jones's 1988 self-titled solo album, and is featured in the official video for Jones's single "Just Wanna Hold"; Joel can be seen playing the piano while his then-wife Christie Brinkley joins him and kisses him. Joel also revamped his backing band, dismissing everyone but drummer Liberty DeVitto, guitarist David Brown, and saxophone player Mark Rivera, and bringing in new faces, including multi-instrumentalist Crystal Taliefero.

Storm Front's second single, "I Go to Extremes" reached No. 6 in early 1990. The album was also notable for its song "Leningrad", written after Joel met a clown in the Soviet city of that name during his tour in 1987, and "The Downeaster Alexa", written to underscore the plight of fishermen on Long Island who are barely able to make ends meet. Another well-known single from the album is the ballad "And So It Goes" (No. 37 in late 1990). The song was originally written in 1983, around the time Joel was writing songs for An Innocent Man; but "And So It Goes" did not fit that album's retro theme, so it was held back until Storm Front. Joel said in a 1996 Masterclass session in Pittsburgh that Storm Front was a turbulent album and that "And So It Goes", as the last song on the album, portrayed the calm and tranquility that often follows a violent thunderstorm.

In the summer of 1992, Joel filed a US$90 million lawsuit against his former lawyer Allen Grubman, alleging a wide range of offenses including fraud, breach of fiduciary responsibility, malpractice and breach of contract.[76] The case was settled out of court in the fall of 1993 for US$3 million paid to Joel by third party Sony America, to protect its subsidiary Sony Music's interests, as it had several other artists also using Grubman's law firm.[77][78]

In 1992, Joel inducted the R&B duo Sam & Dave into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. That year, Joel also started work on River of Dreams, finishing the album in early 1993. Its cover art was a colorful painting by Christie Brinkley that was a series of scenes from each of the songs on the album. The eponymous first single was the last top 10 hit Joel has penned to date, reaching No. 3 on Billboard's Hot 100 and ranking at No. 21 on the 1993 year-end chart. In addition to the title track, the album includes the hits "All About Soul" (with Color Me Badd on backing vocals) and "Lullabye (Goodnight, My Angel)", written for his daughter, Alexa. A radio remix version of "All About Soul" can be found on The Essential Billy Joel (2001), and a demo version appears on My Lives (2005).

The song "The Great Wall of China" was written about his ex-manager Frank Weber and was a regular in the setlist for Joel's 2006 tour. "2000 Years" was prominent in the millennium concert at Madison Square Garden, December 31, 1999, and "Famous Last Words" closed the book on Joel's pop songwriting for more than a decade.

1994–2013: Touring and new singles

[edit]

Beginning in 1994, Joel toured extensively with Elton John on a series of "Face to Face" tours, making them the longest running and most successful concert tandem in pop music history.[79] During these shows, the two played their own songs, sang each other's songs, and performed duets. They grossed over US$46 million in just 24 dates in their sold out[80] 2003 tour. Joel and John resumed their Face to Face tour in March 2009[80] and it continued until March 2010, where it ended in Albany, New York, at the Times Union Center. In February 2010, Joel denied rumors in the trade press that he canceled a summer 2010 leg of the tour, claiming there were never any dates booked and that he intended to take the year off.[81] Joel told Rolling Stone: "We'll probably pick it up again. It's always fun playing with him."[82]

Joel and Christie Brinkley announced on April 13, 1994, that they had separated, and their divorce was finalized in August 1994. The two remained friends.[83]

Joel's Greatest Hits Volume III yielded "To Make You Feel My Love" (a Bob Dylan cover) and "Hey Girl". Joel wrote and recorded the song "Shameless" that was later recorded by Garth Brooks and reached No. 1 on Billboard's country charts. Joel performed with Brooks during his Central Park concert in 1997. Joel was inducted into the Rock 'n Roll Hall of Fame in 1999. Ray Charles made the induction speech and mentioned the duet Joel wrote for the two of them, "Baby Grand" (a track on Joel's album The Bridge released in 1986).

On December 31, 1999, Joel performed at New York's Madison Square Garden. At the time, Joel said that it would be his last tour and possibly his last concert. Two of his performances from that night, "We Didn't Start the Fire" and "Scenes from an Italian Restaurant" were filmed and featured that night as part of ABC's special New Year's Y2K coverage. The concert (dubbed The Night of the 2000 Years) ran for close to four hours and was later released as 2000 Years: The Millennium Concert.

In 2001, Joel released Fantasies & Delusions, a collection of classical piano pieces composed by Joel and performed by Hyung-ki Joo. Joel often uses bits of these pieces as interludes in live performances, and some of them are part of the score for the hit show Movin' Out. The album topped the classical charts at No. 1. Joel performed "New York State of Mind" live on September 21, 2001, as part of the America: A Tribute to Heroes benefit concert, and on October 20, 2001, along with "Miami 2017 (Seen the Lights Go Out on Broadway)", at the Concert for New York City in Madison Square Garden. That night, he also performed "Your Song" with Elton John.

In 2003, Joel inducted The Righteous Brothers into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, noting that his song "Until the Night" from the album 52nd Street was a tribute to the duo.

In 2005, Columbia released a box set, My Lives, which is largely a compilation of demos, b-sides, live/alternative versions, and even a few Top 40 hits. The compilation also includes the software that permits people to remix "Zanzibar" and a live version of "I Go to Extremes" with their PC. A DVD of a show from the River of Dreams tour is included.

On January 7, 2006, Joel began a tour across the U.S. Having not released any new songs in 13 years, he featured a sampling of songs from throughout his career, including major hits as well as deep cuts like "Zanzibar" and "All for Leyna". His tour included an unprecedented 12 sold-out concerts over several months at Madison Square Garden. The singer's stint of 12 shows at Madison Square Garden broke a previous record set by Bruce Springsteen, who played 10 sold-out shows at the same arena. The record earned Joel the first retired number (12) in the arena owned by a non-athlete. This honor has also been given to Joel at the Wells Fargo Center (formerly the Wachovia Center) in Philadelphia, where a banner in the colors of the Philadelphia Flyers is hung honoring Joel's 48 sold-out Philadelphia shows. On June 13, 2006, Columbia released 12 Gardens Live, a double album containing 32 live recordings from a collection of the 12 different shows at Madison Square Garden during Joel's 2006 tour.

Joel visited the United Kingdom and Ireland for the first time in many years as part of the European leg of his 2006 tour. On July 31, 2006, he performed a free concert in Rome, with the Colosseum as the backdrop.[84]

Joel toured South Africa, Australia, Japan and Hawaii in late 2006, and subsequently toured the Southeastern U.S. in February and March 2007 before hitting the Midwest in the spring of 2007. A new song, titled "All My Life", was Joel's newest single (with second track "You're My Home", live from Madison Square Garden 2006 tour) and was released in stores on February 27, 2007.[85] On February 4, Joel sang the national anthem for Super Bowl XLI, becoming the second to sing the national anthem twice at a Super Bowl, after Aaron Neville.

On December 1, 2007, Joel premiered his new song "Christmas in Fallujah".[86] The song was performed by Cass Dillon, a new Long Island based musician, as Joel felt it should be sung by someone in a soldier's age range (though he himself has played the song occasionally in concert.) The track was dedicated to servicemen based in Iraq. Joel wrote it in September 2007 after reading numerous letters sent to him from American soldiers in Iraq. "Christmas in Fallujah" is only the second pop/rock song released by Joel since 1993's River of Dreams. Proceeds from the song benefited the Homes For Our Troops foundation.

On January 26, 2008, Joel performed with the Philadelphia Orchestra celebrating the 151st anniversary of the Academy of Music. Joel performed his classical piece "Waltz No. 2 (Steinway Hall)" from Fantasies & Delusions, arranged by Brad Ellis. He also played many of his less well-known pieces, with full orchestral backing arranged by Mr. Ellis, including the rarely performed Nylon Curtain songs "Scandinavian Skies" and "Where's the Orchestra?".

On March 10, 2008, Joel inducted his friend John Mellencamp into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Joel sold out 10 concerts at the Mohegan Sun Casino in Uncasville, Connecticut from May to July 2008. The casino honored him with a banner displaying his name and the number 10 to hang in the arena. On June 19, 2008, he played a concert at the grand re-opening of Caesars Windsor (formerly Casino Windsor) in Windsor, Ontario, Canada, to an invite-only crowd for Casino VIPs. His mood was light and joke-filled, even introducing himself as "Billy Joel's dad" and stating "you guys overpaid to see a fat bald guy". He also admitted that Canadian folk-pop musician Gordon Lightfoot was the musical inspiration for "She's Always A Woman".[87][failed verification]

On July 16 and 18, 2008, Joel played the final concerts at Shea Stadium before its demolition. His guests included Tony Bennett, Don Henley, John Mayer, John Mellencamp, Steven Tyler, Roger Daltrey, Garth Brooks and Paul McCartney. The concerts were featured in the 2010 documentary film Last Play at Shea. The film was released on DVD on February 8, 2011. The CD and DVD of the show, Live at Shea Stadium, were released on March 8, 2011.

On December 11, 2008, Joel recorded his own rendition of "Christmas in Fallujah" during a concert at Acer Arena in Sydney and released it as a live single in Australia only. It is the only official release of Joel performing "Christmas in Fallujah", as Cass Dillon sang on the 2007 studio recording and the handful of times the song was played live in 2007. Joel sang the song throughout his December 2008 tour of Australia.

On May 19, 2009, Joel's former drummer, Liberty DeVitto, filed a lawsuit in NYC claiming Joel and Sony Music owed DeVitto over 10 years of royalty payments. DeVitto had never been given songwriting or arranging credit on any of Joel's songs, but he claimed that he helped arrange some of them, including "Only the Good Die Young".[88] In April 2010, it was announced that Joel and DeVitto amicably resolved the lawsuit.[89]

2011 marked the 40th anniversary of the release of Joel's debut album, Cold Spring Harbor. According to Joel's official website, to commemorate this anniversary, Columbia/Legacy Recordings originally planned "to celebrate the occasion with a definitive reissue project of newly restored and expanded Legacy editions of Joel's complete catalog, newly curated collections of rarities from the vaults, previously unavailable studio tracks and live performances, home video releases and more", although this never fully came to fruition.[90] Piano Man was re-released in a two-disc Legacy edition in November 2011.[90]

In 2012, Joel signed an exclusive worldwide publishing agreement with Universal Music Publishing Group (UMPG), and its subsidiary Rondor Music International. Under the agreement, UMPG and Rondor replaced EMI Music Publishing in handling Joel's catalog outside the US. Additionally, the agreement marked the first time since Joel regained control of his publishing rights in the 1980s that he began to use an administrator to handle his catalog within the U.S. The agreement's focus is on increasing the use of Joel's music in movies, television programs and commercials.[91]

On December 12, 2012, Joel performed as part of 12-12-12: The Concert for Sandy Relief at Madison Square Garden, a concert held for all the victims of Hurricane Sandy. He changed the lyrics to "Miami 2017 (Seen the Lights Go Out on Broadway)" to make it relate to all the damage caused by Sandy.

In May 2013, it was announced that Joel would hold his first ever indoor Irish concert at the O2 in Dublin on November 1. He subsequently announced his return to the UK for the first time in seven years to perform in October and November. Joel played in Manchester and Birmingham as well as London's Hammersmith Apollo.[92][93] In October, Joel held a surprise concert on Long Island at The Paramount (Huntington, New York) to benefit Long Island Cares. The venue holds a capacity of 1,555 and sold out in five minutes. Joel headlined a solo arena concert in New York City for the first time since 2006 when he performed at Barclays Center in Brooklyn on December 31, 2013.

2014–present: Madison Square Garden residency and "Turn the Lights Back On"

[edit]Joel announced a concert residency at Madison Square Garden, playing one concert a month indefinitely, starting January 27, 2014.[94] The first MSG show also launched the Billy Joel in Concert tour, which continued at the Amway Center (in Orlando, Florida) where Joel performed several cover songs such as Elton John's "Your Song", Billy Preston's "You Are So Beautiful" (in tribute to Joe Cocker), The Beatles' "With a Little Help from My Friends", "Can't Buy Me Love" and "When I'm 64", Robert Burns' "Auld Lang Syne" and AC/DC's "You Shook Me All Night Long" (with Brian Johnson). Joel also performed an unusual set, including the song "Souvenir" (from 1974's Streetlife Serenade) and excluding "We Didn't Start the Fire".[95]

In 2015, Joel performed 21 concerts in addition to his monthly Madison Square Garden residency. His August 4, 2015, engagement at Nassau Coliseum was the final concert prior to the arena undergoing a US$261 million renovation.[96] Joel returned to Nassau Coliseum on April 5, 2017, to play the first concert at the newly renovated venue.[97] Later that month, he played the first concert at Atlanta's new SunTrust Park, the suburban home of the Atlanta Braves.[98] On June 24, 2017, he returned to Hicksville High School fifty years after his would-be graduating class received their diplomas,[99] to deliver the honorary commencement address. It was also the 25th anniversary of receiving his own diploma from the same high school.

In 2019, Joel announced a concert at Camden Yards, home of the Baltimore Orioles, marking the first-ever concert at the baseball stadium.[100] Joel was forced to postpone his concerts between March 2020 and August 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Joel and Stevie Nicks jointly announced plans to perform a series of concerts across the United States in 2023, tentatively beginning with SoFi Stadium outside Los Angeles on March 10.[101]

On June 1, 2023, Joel announced that his residency at Madison Square Garden would end in July 2024 with his 104th performance in the series, marking his 150th lifetime performance at the venue.[102] On January 22, 2024, he announced his first new pop single in years (and only his second pop song in more than two decades), "Turn the Lights Back On", which was released on February 1.[103][104]

Other ventures

[edit]In 1996, Joel merged his long-held love of boating with his desire for a second career. He and Long Island boating businessman Peter Needham formed the Long Island Boat Company.[105][106]

In November 2010, Joel opened a shop in Oyster Bay, Long Island, to manufacture custom-made, retro-styled motorcycles and accessories.[107]

In 2011, Joel announced that he was releasing an autobiography that he had written with Fred Schruers, titled The Book of Joel: A Memoir. The book was originally going to be released in June 2011, but, in March 2011, Joel decided against publishing the book and officially canceled his deal with HarperCollins. Rolling Stone noted, "HarperCollins acquired the book project for US$3 million in 2008. Joel is expected to return his advance on that sum to the publisher."[108] According to Billboard, "the HarperCollins book was billed as an 'emotional ride' that would detail the music legend's failed marriage to Christie Brinkley, as well as his battles with substance abuse."[109] In explaining his decision to cancel the book's release, Joel said, "It took working on writing a book to make me realize that I'm not all that interested in talking about the past, and that the best expression of my life and its ups and downs has been and remains my music."[110] In 2014, Schruers published a biography, simply titled Billy Joel, based on his extensive personal interviews with Joel.[111]

Personal life

[edit]Marriages and family

[edit]

Joel's first wife was Elizabeth Weber Small. When their relationship began, she was married to Jon Small, his music partner in the short-lived duo Attila, with whom she had a son. When the affair was revealed, Weber severed her relationships with both men. Weber and Joel later reconciled and married in 1973, and she then became his manager. They divorced on July 20, 1982.[112]

Joel married a second time, to model Christie Brinkley, in March 1985.[113] Their daughter, Alexa Ray Joel, was born December 29, 1985.[113][114] Alexa was given the middle name of Ray after Ray Charles, one of Joel's musical idols.[115] Joel and Brinkley divorced on August 26, 1994.[116] They remain friends; Joel is the godfather of Brinkley's two youngest children Jack and Sailor Brinkley Cook.[117][118]

On October 2, 2004, Joel married chef Katie Lee, his third wife.[119] At the time of the wedding, Lee was 23 and Joel was 55. Joel's daughter, Alexa Ray, then 18, served as maid of honor. Joel's second wife, Christie Brinkley, attended the union and gave the couple her blessing. On June 17, 2009, they announced their separation.[120]

On July 4, 2015, Joel married a fourth time, to Alexis Roderick, an equestrian and former Morgan Stanley executive, at his Oyster Bay estate on Long Island. He was 66; she was 33. Governor of New York Andrew Cuomo conducted the ceremony.[121] The couple have been together since 2009.[122] On August 12, 2015, the couple had a daughter, Della Rose Joel.[123] The couple's second daughter, Remy Anne Joel, was born on October 22, 2017.[124]

Joel bought an estate in Centre Island, New York in the town of Oyster Bay, in 2002 for US$22 million. He also owns a house in Sag Harbor.[125] In 2023, Joel put his Oyster Bay estate on the market for $49 million.[126] The listing was pulled as the main house was undergoing renovations. The mansion, with its guest houses, pool, beach and helipad on 26 acres, was again offered for sale in September 2024, asking $49.9 million. Joel has ended his 10-year residency at Madison Square Garden in Manhattan in July 2024. His two younger daughters attend school in Florida, where the family now lives.[127][128]

In 2015, he purchased a home in Manalapan, Florida. The waterfront residence went on the market in November 2015 for $19.5 million[129] but it was taken off the market and re-listed in 2017 with an asking price of $18.5 million.[130] The property was further reduced to $16.9 million in 2018.[129] In January 2020, the 13,200-square-foot property sold for US$10.3 million.[131]

Health issues

[edit]Many speculate that Joel lives with depression; however, he rejects the label.[132][failed verification] Regardless, in 1970, a career decline and personal tragedies led him to a deep depressive period. Joel left a suicide note and attempted to end his life by drinking furniture polish. Later he said, "I drank furniture polish. It looked tastier than bleach."[42] His drummer and bandmate, Jon Small, rushed him to the hospital. Joel checked into Meadowbrook Hospital, where he was put on suicide watch and received treatment for depression.[133] Joel would later pen the song "Tomorrow Is Today", which he describes as a suicide note.[42]

In 1985, Joel recorded "You're Only Human (Second Wind)" as a message to help prevent teen suicide.[134]

In 2002, Joel entered Silver Hill Hospital, a substance abuse and psychiatric center in New Canaan, Connecticut, where he underwent treatment for 10 days.[135] In March 2005, he checked into the Betty Ford Center,[136] where he spent 30 days for the treatment of alcohol abuse.[137]

Politics

[edit]Although Joel has donated money to Democratic candidates,[138] he has never publicly affiliated himself with the Democratic Party. Joel rarely publicly endorses political candidates, however he did play a benefit with his friend Bruce Springsteen to raise money for Barack Obama's presidential campaign in 2008.[139] He has performed at benefit concerts that have helped raise funds for political causes. However, about celebrities endorsing political candidates, Joel has said, "People who pay for your tickets, I don't think they want to hear who you're going to vote for and how you think they should vote."[140]

In 2016, after his sarcastic dedication of "The Entertainer" to then-Republican candidate Donald Trump[141] was taken as a serious endorsement, Joel told the New York Daily News in an email that he would be voting for Hillary Clinton.[142]

Tours

[edit]Tours

- Cold Spring Habor Tour (1972)

- Turntiles Tour (1976)

- The Stranger Tour (1977)

- 52nd Street Tour (1978)

- The Nylon Curtain Tour (1981)

- An Innocent Man Tour (1984)

- The Bridge Tour (1986–87)

- Storm Front Tour (1989–91)

- River of Dreams Tour (1993–95)

- Face To Face 1994 Tour (1994)

- Face To Face 1995 Tour (1995)

- An Evening of Questions and Answers (1996)

- Face To Face 1998 Tour (1998)

- Face To Face 2001 Tour (2001)

- Face To Face 2002 Tour (2002)

- Face To Face 2003 Tour (2003)

- 2006 Tour (2006)

- 2007 Tour (2007)

- 2008 Tour (2008)

- Face To Face 2009 Tour (2009)

- Face To Face 2010 Tour (2010)

- Billy Joel in Concert (2014–)

- Two Icons - One Night (2023)

- Two Icons - One Night (2024)

Residency

- Billy Joel At The Garden (2014–2024)

Discography

[edit]- Cold Spring Harbor (1971)

- Piano Man (1973)

- Streetlife Serenade (1974)

- Turnstiles (1976)

- The Stranger (1977)

- 52nd Street (1978)

- Glass Houses (1980)

- The Nylon Curtain (1982)

- An Innocent Man (1983)

- The Bridge (1986)

- Storm Front (1989)

- River of Dreams (1993)

- Fantasies & Delusions (2001), classical compositions

Awards and achievements

[edit]

Joel graduated well after his high school peers because of a missed English exam.[143] His high school diploma was finally awarded by the school board 25 years later.[31] Joel has been presented with multiple honorary doctorates:[144]

- Doctor of Humane Letters from Fairfield University (1991)

- Doctor of Music from Berklee College of Music (1993)

- Doctor of Humane Letters from Hofstra University (1997)

- Doctor of Music from Southampton College (2000)

- Doctor of Fine Arts from Syracuse University (2006)[145]

- Doctor of Musical Arts from the Manhattan School of Music (2008)

- Doctor of Music from Stony Brook University (2015)

In 1986, Joel was on the site selection committee for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame board. Seven members of the committee voted for the Hall to be located in San Francisco, and seven voted for Cleveland, Ohio; this tie was broken when Joel voted for Cleveland. Joel was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland in 1999 by one of his chief musical influences, Ray Charles, with whom he also collaborated on his song "Baby Grand" (1986).

Joel was also named MusiCares Person of the Year for 2002,[146] an award given each year at the same time as the Grammy Awards. At the dinner honoring him, various artists performed versions of his songs, including Nelly Furtado, Stevie Wonder, Jon Bon Jovi, Diana Krall, Rob Thomas and Natalie Cole.

Joel has won five Grammys, including Album of the Year for 52nd Street and Song of the Year and Record of the Year for "Just the Way You Are".

In 1993, Joel was the second entertainer out of thirty persons to be inducted into the Madison Square Garden Walk of Fame.[147] On September 20, 2004, Joel received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, for his work in the music industry, located at 6233 Hollywood Boulevard.[148][149][150] He was inducted into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame on October 15, 2006.

Joel is the only performing artist to have played both Yankee and Shea Stadiums, as well as Giants Stadium, Madison Square Garden, and Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum. Joel has banners in the rafters of the MVP Arena, Nassau Coliseum, Madison Square Garden, Mohegan Sun Arena in Uncasville, Connecticut, Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia, Hartford Civic Center in Hartford, and the JMA Wireless Dome in Syracuse.

In 2003, Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list included The Stranger at number 67,[151] and 52nd Street at number 352.[152] On their 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list, Rolling Stone included "Piano Man" at number 421.[153]

Joel has also sponsored the Billy Joel Visiting Composer Series at Syracuse University.[154]

On December 12, 2011, Joel became the first non-classical musician honored with a portrait in Steinway Hall.[155]

On December 29, 2013, in Washington, D.C., Joel received Kennedy Center Honors, the nation's highest honor for influencing American culture through the arts.[156]

On July 22, 2014, the Library of Congress announced that Joel would be the sixth recipient of the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.[157] He received the prize at a performance ceremony in November 2014 from James H. Billington, the Librarian of Congress, and Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor.[158]

On July 18, 2018, Governor Andrew Cuomo proclaimed the date to be Billy Joel Day in New York state to mark his 100th performance at Madison Square Garden.[159]

On October 19, 2023, a portion of Audrey Avenue in Joel's hometown of Oyster Bay was renamed "Billy Joel Way" in honor of the musician.[160]

On April 14, 2024, Joel was featured on CBS in commemoration of his 100th performance at Madison Square Garden.[161] The network broadcast an encore presentation of the concert special five nights later, on April 19.[162]

In 2024, Joel was honored in "Group C Premiere: Billy Joel Night," on The Masked Singer Season 11. The contestants that night sang songs by Joel.

Awards and nominations

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2006). "Billy Joel Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 9, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ a b "Billy Joel's Concert History". Concert Archives. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Johnstone, Andrew (February 6, 2015). "A General Guide to Soft Rock". Rip It Up. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (December 18, 2022). "Billy Joel Postpones Madison Square Garden Show Due to Viral Infection and Vocal Rest". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 28, 2022. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ Fortier, Marc (December 8, 2022). "Billy Joel, Stevie Nicks to Play Gillette Stadium in 2023. Here's How to Get Tickets". NBC Boston. Archived from the original on December 28, 2022. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ Gamboa, Glenn (September 12, 2013). "Billy Joel named Kennedy Center honoree". Newsday. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ^ "Top Selling Artists". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ "Thirty-Three-Hit Wonder". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ "Billy Joel". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ "Billy Joel: Johnny Mercer Award". Songwriters Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ "Billy Joel". The Kennedy Center.

- ^ "A long-lost Billy Joel song surfaces on 'This Is Us'". 987theriver.iheart.com. 98.7 The River. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Billy Joel". Here's The Thing. WNYC. July 30, 2012. Archived from the original (transcript) on August 4, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

I grew up on the Island, in the Levittown section of Hicksville. We had a Levitt house, Cape Cod, on the quarter acre. ... My father was a classically trained pianist. He grew up in Nuremberg, Germany, and he also went to school in Switzerland. His father was quite well off. They had a mail-order textile business, Joel Macht Fabrik ...

- ^ "Billy Joel's mom dies at 92". Newsday. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Bego, Mark (2007). Billy Joel: The Biography. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 13. ISBN 9781560259893.

- ^ a b c d e f g Joel, Billy (1993). "Billy Joel Interview". The Charlie Rose Show (Interview). Interviewed by Charlie Rose. PBS. Archived from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Tallmer, Jerry (July 22, 2003). "Billy Joel grapples with the past". The Villager. Vol. 73, no. 11. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Biography". alexanderjoel.com. Alexander Joel. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ Gelder, Lawrence Van (April 27, 1986). "Long Islanders; A Pianist Finds 88 Keys to Happiness". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ Bordowitz, Hank (2006). Billy Joel: The Life and Times of an Angry Young Man. Billboard Books. p. 26. ISBN 9780823082506.

- ^ "Billy Joel: The Piano Man In A New York State Of Mind". KCBS-TV. December 17, 2013. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ "Billy Joel". classicbands.com. 2007. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ "Billy Joel biography shows the ugly side of music legend". J. August 23, 2007. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ Paumgarten, Nick (October 27, 2014). "Thirty-Three-Hit Wonder". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ "Billy Joel". celebatheists.com. Celebrity Atheists List. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ "Photos: Famous atheists and their beliefs". CNN. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Rob (July 15, 2001). "Dear Superstar: Billy Joel". Blender. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ^ Menta, Anna (April 1, 2018). "'Atheist Day' 2018: Billy Joel, Emma Thompson and More On Why God May Not Exist". Newsweek. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ Bordowitz, Hank (2006). Billy Joel: The Life and Times of an Angry Young Man. Billboard Books. p. 22. ISBN 9780823082483.

- ^ a b Brozan, Nadine (June 26, 1992). "Chronicle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Tamarkin, Jeff. "Joel, Billy". Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Crandall, Bill (February 6, 2014). "10 musicians who saw the Beatles standing there". CBS News. Archived from the original on February 7, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "Billy Joel Biography". Sing365.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ^ "Billy Joel with Howard Stern on Sirius Radio" (Interview). Sirius Radio. November 24, 2010. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2020 – via BluebirdReviews.com.

- ^ "Billy Joel: 1994 Recipient of The Century Award". Billboard. December 3, 1994. p. 13. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ "Leiber – Stoller – Goldner Present The Shangri-Las [advertisement]". Billboard. August 15, 1964. p. 5. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ Schruers, Fred (2014). Billy Joel: The Definitive Biography. New York: Crown Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8041-4019-5. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ Proefrock, Stacia. "Attila". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Goodman, Fred (March 1991). "An Innocent Man". Spy: 73. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Cold Spring Harbor Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ^ "Major 7th chords – a talk with Billy Joel". The Actors Studio, USA. 1999.

- ^ The Last Play at Shea (documentary film). 2010. Interview with Yetnikoff.[when?]

- ^ Holden, Stephen (October 29, 2010). "Brenda, Eddie, Billy and Friends Bury a Ballpark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012.

- ^ Chesher Cat. "Everybody I Shot is Dead". everybodyishotisdead.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: J". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Archived from the original on May 25, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (December 5, 1974). "Billy Joel Streetlife Serenade > Album Review". Rolling Stone. No. 175. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- ^ "The Return of 'The Stranger' – 30th Anniversary Legacy Edition of Billy Joel's Top-Selling..." Reuters. July 31, 2008. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Schruers, Fred (2015). Billy Joel: The Definitive Biography. Three Rivers Press. p. 130.

- ^ Webb, Craig (2016). The Dreams Behind the Music: Learn Creative Dreaming As 100+ Top Artists Reveal Their Breakthrough Inspirations. p. 76. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Billy Joel Grammy Awards Archived December 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine at The Recording Academy

- ^ "Joel on 'Scenes': I couldn't do a show without it". Newsday. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ Barry, Dan (July 13, 2008). "Just the Way He Is". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ "Billy Joel's Top 5 Favorite Songs Playlist". January 11, 2017. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Grierson, Tim (April 17, 2022). "How Billy Joel's 'Vienna' Went from a Deep Cut to His Most Popular Song". MEL Magazine. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time: Billy Joel, 'The Stranger'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "article on Havana Jam". People. March 19, 1979. Archived from the original on November 20, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- ^ "How Billy Joel's '52nd Street' Became the First Compact Disc Released". Ultimate Classic Rock. October 2012. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Kozak, Roman (August 9, 1980). "Singer Alters Summer Tour: Double LP Set For November?". Billboard. Vol. 92, no. 32. p. 35. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via Google books.

- ^ Melhuish, Martin (September 10, 1980). "The Pringle Column". The Interior News. Smithers, British Columbia. Sun Media. p. b7. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Joel, Billy, Billy Joel – Masterclass concert (Part 1) – 2001, University of Pennsylvania

- ^ a b Billy Joel on The Nylon Curtain – from The Complete Albums Collection. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "35 Years Ago: Billy Joel Injures Both Hands in Motorcycle Accident". Ultimate Classic Rock. April 15, 2017. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Stephen. "An Innocent Man – Billy Joel : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ YouTube (uploaded April 6, 2008).

- ^ Billy Joel's Interview on Howard Stern. 2011.[which?]

- ^ Heatley, Michael; Hopkinson, Frank (November 24, 2014). The Girl in the Song: The Real Stories Behind 50 Rock Classics. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1909396883. Retrieved January 28, 2017 – via Google Books.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Sinagra, Laura (January 24, 2006). "At Garden, Billy Joel Is Out to Prove He's in Control". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c Ozzi, Dan (July 27, 2017). "30 Years Ago, Billy Joel Had a Meltdown in Moscow". Vice. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Hewlett, Anderson. "Pete Hewlett". Hewlett Anderson: Bios. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ Sauter, Michael (August 9, 1996). "Billy Joel rocked the USSR in 1987". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ "Letters to the Editor". Seattle Weekly. November 14, 2007. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ "Billy Joel Blows His Cool, Upsets Piano in Moscow". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. July 27, 1987. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ Pore-Lee-Dunn Productions (February 4, 2007). "Billy Joel". Classicbands.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Fabrikant, Geraldine (September 24, 1992). "Billy Joel takes his lawyers to court". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 28, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "Profiles – Billy Joel". CityFile.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Fabrikant, Geraldine (May 3, 1995). "THE MEDIA BUSINESS; A Tangled Tale of a Suit, A Lawyer and Billy Joel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ Concerts: Billy Joel & Elton John Archived January 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. tampabay.metromix.com. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Evans, Rob (December 2, 2008). "Elton John, Billy Joel plan more 'Face 2 Face' time Archived December 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine". LiveDaily. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ Billy Joel: "There Was Never a Tour Booked This Summer!". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 10, 2010. Archived April 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Billy Joel Dismisses Rumors He Yanked Tour With Elton John". Rolling Stone. February 26, 2010. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Clarke, Eileen (April 20, 2001). "A Matter Of Trust". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Joel and Adams in free Rome concert". Irish Examiner. August 1, 2006. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Cohen, Jonathan (January 30, 2007)."Bily Joel Returns To Pop With New Single". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved December 9, 2008.. Billboard. Archived from the original Archived August 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine on October 12, 2007.

- ^ "Emerging Singer-Songwriter Cass Dillon Premiers New Billy Joel Song, 'Christmas in Fallujah', Exclusively on iTunes Beginning Tuesday, December 4". billyjoel.com (Press release). Billy Joel. November 30, 2007. Archived from the original on February 7, 2008.

- ^ "Billy Joel (notes)". The Windsor Star. June 20, 2008.

- ^ Westerly, Mal (May 24, 2009). "Billy Joel's Former Drummer Files Lawsuit, Liberty DeVitto Says He's Owed $$$". MusicNewsNet.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved May 24, 2009.

- ^ "Billy Joel and Former Drummer, Liberty Devitto Settle Lawsuit". MusicNewsNet.com. April 22, 2010. Archived from the original on April 27, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ a b "Billy Joel Catalog To Be Reissued, Commemorative CDs/DVDs To Be Released". billyjoel.com (Press release). October 20, 2010. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Christman, Ed (August 30, 2012). "Exclusive: Billy Joel Signs Global Publishing Deal With Rondor and Universal". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ "Billy Joel delivers a knock-out show". The Daily Telegraph. London, England. November 7, 2013. p. 36. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "Piano Man remains as proudly unhip as ever". The Daily Telegraph. London, England. October 25, 2013. p. 33. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Gardner, Elysa (December 3, 2013). "Meet Madison Square Garden's new franchise: Billy Joel". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ "Billy Joel". Archived from the original on July 24, 2015.

- ^ "Billy Joel gives Nassau Coliseum epic sendoff". Newsday. Archived from the original on August 7, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ "Movin' Back In: Billy Joel Plays First Concert at Renovated Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Long Island". Billboard. April 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 27, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "Billy Joel show prompts mixed reviews of SunTrust Park as concert venue". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ "Fifty years later, Billy Joel addresses Hicksville High grads". Newsday. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ "Billy Joel to hold first concert in Camden Yards history". The Baltimore Sun. January 10, 2019. Archived from the original on January 12, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ Bowenbank, Starr (November 11, 2022). "Billy Joel & Stevie Nicks to Co-Headline 2023 Stadium Concerts: How to Buy Tickets". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 23, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (June 1, 2023). "Billy Joel Will End Madison Square Garden Residency in 2024". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Newman, Melinda (January 22, 2024). "Billy Joel to Release First Pop Single in Years". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 22, 2024. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "New Billy Joel: Stream "Turn the Lights Back On," His First New Song in Decades — Playing the Grammys Sunday, Feb. 4". February 2024. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Timothy K. (September 20, 2004). "The Piano Man Builds His Dream Boat Billy Joel has always loved watercraft. But now he has commissioned—and is helping design—a fantastic commuter yacht straight out of the golden age of powerboats". CNN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Billy Joel Timeline Archived March 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Dipity.com. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ Karppi, Dagmar Fors (January 21, 2011). "Billy Joel Adds to OB Mix As Chamber Members Chat". Oyster Bay Enterprise Pilot. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ Perpetua, Matthew (March 31, 2011). "Billy Joel Scraps Plans to Release Memoir". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Nekesa Mumbi Moody (March 31, 2011). "Billy Joel Cancels 'Book of Joel' Memoir". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "Billy Joel Cancels 'Book of Joel'" (Press release). Billyjoel.com. March 31, 2011. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "Book Review: Billy Joel Biography Contains Lots of Juice But Many Skeletons Stay Closeted". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Elizabeth A. Weber". Hollywood.com. November 20, 2014. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ a b "Brinkley, Joel Parents of 'Uptown Girl'" . Los Angeles Times, December 30, 1985. p. 2. "The 6+1⁄2-pound girl, as yet unnamed, was born in a Manhattan hospital at about 11:45 pm Sunday, said the spokeswoman, Geraldine McInerney." "They were married last March aboard a yacht in New York Harbor."

- ^ "Joel and his 'uptown girl' have a girl". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 31, 1985. p. A3. "Model Christie Brinkley has given her husband – singer-songwriter Billy Joel – something new to sing about, a 6+1⁄2-pound daughter, a spokesman for the family said Monday."

- ^ Stout, Gene (December 3, 1986). "Billy Joel Delivers – Few Surprises". seattlepi.com. Retrieved December 8, 2008. Archived copy at WebCite (July 28, 2010).

- ^ "Big Billy Joel moments in August: Della Rose Joel was born, Christie Brinkley divorce and more". Newsday. Long Island, New York. August 1, 2017. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Belus, Amber (February 16, 2018). "Sailor Brinkley Cook Details Her Relationship With Billy Joel". Closer Weekly. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Christie Brinkley Shares Video of Daughter Sailor, 25, Giving 'Uncle Billy' Joel Pointers Before His Concert". People.com. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Age-Defying Duos". People. Vol. 62, no. 16. October 18, 2004. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Rush, George (June 17, 2009). "Billy Joel and wife Katie Lee split". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2009.

- ^ "Billy Joel Becomes a Father Again — at 66". Celebrity Gossip & News – Yahoo Celebrity Canada. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015.

- ^ "Billy Joel Marries Alexis Roderick in Surprise Wedding at His Estate". People. July 4, 2015. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ^ "Billy Joel Welcomes Daughter Della Rose". People. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Nelson, Jeff (October 23, 2017). "Billy Joel Welcomes Third Daughter Remy Anne: See the First Photo!". People. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Anorim, Kevin. "A Billy Joel Tour of Long Island". Newsday. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ Clarke, Katherine (May 12, 2023). "Billy Joel Is Movin' Out of His $49 Million Long Island Mansion". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 8, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Callimachi, Rukmini (October 10, 2024). "Billy Joel Is Selling the Mansion He First Saw While Dredging Oysters". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

As fans of the working-class nostalgia embedded in his songs filled up Madison Square Garden again and again, Mr. Joel headed to the arena by helicopter — a 13-minute ride from tail up to tail down — from his helipad.

- ^ Dresdale, Andrea (July 26, 2024). "Billy Joel ends historic Madison Square Garden residency with epic show". ABC News. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ a b "See Inside Billy Joel's Florida Home". Town & Country. May 1, 2018. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Kallergis, Katherine (April 9, 2018). "Billy Joel sells waterfront Manalapan property; His mansion next door is asking $16.9M". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ Hofheinz, Darrell (November 30, 2022). "Did Billy Joel's company pay $9M for a Palm Beach townhome? That's what records suggest". Palm Beach Daily News. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved December 20, 2023.