Big naked-backed bat

| Big naked-backed bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Mormoopidae |

| Genus: | Pteronotus |

| Species: | P. gymnonotus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pteronotus gymnonotus (Wagner, 1843)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The big naked-backed bat (Pteronotus gymnonotus), is a bat species from South and Central America.

Taxonomy

[edit]It was described as a new species in 1843 by German zoologist Johann Andreas Wagner. Wagner placed it in the now-defunct genus Chilonycteris. The holotype had been collected in Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil.[2] Taxon authority is sometimes given to Johann Natterer, however.[3] According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature's Principle of Priority, the first author to publish a species name is considered the authority of that name. Smith (1977) hypothesized that Wagner copied Natterer's species description directly from his diary, and thus gave Natterer the authority. Carter and Dolan (1978) stated that Wagner's description was not comparable to Natterer's, which is why they attribute the name to Wagner.[4] The reference texts Mammals of South America and Mammals of Mexico also list Wagner as the authority.[3][5]

Description

[edit]Instead of attaching to the sides of the bat, its wings attach to its back near its spine. This gives individuals the appearance of having a "naked back" due to the lack of fur on their wings. However, its back is furred under the wings. The fur ranged in color from dark brown to bright orange, being lighter on the underparts. The larger of the two species of naked-backed bat, individuals weigh 12–16 g (0.42–0.56 oz) and have a forearm length of 49–56 mm (1.9–2.2 in). The ears are pointed with a smooth edge, and the nose has a flattened, plate-like shape with small warty tubercles over the nostrils and short spikes to either side.[2]

Like all species in its family, it has a dental formula of 2.1.2.32.1.3.3 for a total of 34 teeth.[5]

Range and habitat

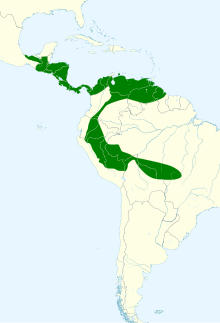

[edit]Big naked-backed bats are found from southeastern Mexico through the whole of Central America and into Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, and Venezuela.[3] They inhabit tropical forests and savannah and are usually found at elevations below 400 m (1,300 ft)[1] although they are sometimes found as high as 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[2] They are adapted to hot environments, and are unable to tolerate temperatures below 15 °C (59 °F) for long.[6]

Behaviour and biology

[edit]The big naked-backed bat roosts in large, humid, cave systems, often in association with many other local bat species; a researcher reported 50,000 individuals roosting together with other bats in two colonies in a karst landscape in Brazil.[7] They feed on insects, mostly moths, beetles, and orthopterans.[8] Their echolocation calls have been reported to have up to three harmonics, with the most intense starting at 55 kHz and falling to 48.7 kHz.[9] When hunting prey the calls can reach a volume of 130 dB.[10]

The breeding season takes place at different times of the year across their range. Mothers give birth to a single, naked, young which is initially raised in a maternity roost that may be shared with other closely related species.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Solari, S. (2019). "Pteronotus gymnonotus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T18706A22077065. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T18706A22077065.en.

- ^ a b c Pavan, A. C.; da C. Tavares, V. (2020). "Pteronotus gymnonotus (Chiroptera: Mormoopidae)". Mammalian Species. 52 (990): 40–48. doi:10.1093/mspecies/seaa003. S2CID 220515608.

- ^ a b c Gardner, A. L. (2008). Mammals of South America, Volume 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews, and Bats. Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press. pp. 381–382. ISBN 978-0226282428.

- ^ Carter, D. C.; Dolan, P. G. (1978). "Catalogue of type specimens of neotropical bats in selected European museums". Special Publications of the Museum: Texas Tech University. 15: 26–27.

- ^ a b Ortega R., J.; Arita, H. T. (2014). Ceballos, G. (ed.). Mammals of Mexico. JHU Press. pp. 747–748. ISBN 978-1421408439.

- ^ Bonaccorso, F.J.; Arends, A.; et al. (May 1992). "Thermal ecology of moustached and ghost-faced bats (Mormoopidae) in Venezuela". Journal of Mammalogy. 73 (2): 365–378. doi:10.2307/1382071. JSTOR 1382071.

- ^ da Rocha, P.A.; Feijó, J.A.; et al. (July 2011). "First records of mormoopid bats (Chiroptera, Mormoopidae) from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest". Mammalia. 75 (3): 295–299. doi:10.1515/mamm.2011.029.

- ^ Whitaker, J.O.; Findlay, J.S. (August 1980). "Foods eaten by some bats from Costa Rica and Panama". Journal of Mammalogy. 61 (3): 540–544. doi:10.2307/1379850. JSTOR 1379850.

- ^ Ibáñez, C.; Lopez-Wilchis, R.; et al. (September 2000). "Echolocation calls and a noteworthy record of Pteronotus gymnonotus (Chiroptera, Mormoopidae) from Tabasco, Mexico". The Southwestern Naturalist. 45 (3): 345–347. doi:10.2307/3672841. JSTOR 3672841.

- ^ Surlykke, A.; Kalko, E.K.V. (April 2008). "Echolocating bats cry out loud to detect their prey". PLOS ONE. 3 (4): e2036. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002036. PMC 2323577. PMID 18446226.

- ^ Deleva, S.; Chaverri, G. (April 2018). "Diversity and conservation of cave-dwelling bats in the Brunca region of Costa Rica". Diversity. 10 (2): 43. doi:10.3390/d10020043. hdl:10669/74851.