Biangbiang noodles

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (September 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| |

| Type | Chinese noodles |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | China |

| Region or state | Shaanxi |

| Biangbiang noodles | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 𰻞𰻞麵 / | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 𰻝𰻝面 / | ||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | biángbiáng miàn | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 油潑扯麵 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 油泼扯面 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | yóupō chěmiàn | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | oil-splashed hand-pulled noodles | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

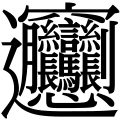

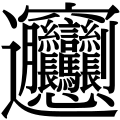

Biangbiang noodles (simplified Chinese: 𰻝𰻝面; traditional Chinese: 𰻞𰻞麵; pinyin: Biángbiángmiàn), alternatively known as youpo chemian (simplified Chinese: 油泼扯面; traditional Chinese: 油潑扯麵) in Chinese, are a type of Chinese noodle originating from Shaanxi cuisine. The noodles, touted as one of the "eight curiosities" of Shaanxi (陕西八大怪),[1] are described as being like a belt, owing to their thickness and length.

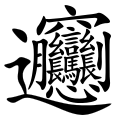

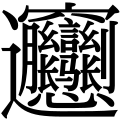

Biangbiang noodles are renowned for being written using a unique character.[2] The character is unusually complex, with the standard variant of its traditional form containing 58 strokes.

Noodles

[edit]

The noodles are thick and belt-like, and are usually hand-made. For most of their existence, they have been an obscure dish local to Xi'an, eaten by workers lacking the time to make thinner noodles. More recently, the noodles have become more widely known across China, in a rise driven to some extent by social media interest in the esoteric character used to write biáng.[1]

The word biáng is onomatopoeic, being said to resemble the sound of the thick noodle dough hitting a work surface.[1]

Chinese character for biáng

[edit]

There are many variations of the character for biáng, but the most widely accepted version is made up of 58 strokes in its traditional form[a] (42 in simplified Chinese). It is one of the most complex Chinese characters in modern usage,[3] although it is not found in modern dictionaries or even in the Kangxi dictionary.

The character is composed of 言 (speak; 7 strokes) in the middle flanked by 幺 (tiny; 2 × 3 strokes) on both sides. Below it, 馬 (horse; 10 strokes) is similarly flanked by 長 (grow; 2 × 8 strokes). This central block itself is surrounded by 月 (moon; 4 strokes) to the left, 心 (heart; 4 strokes) below, and刂 (knife; 2 strokes) to the right. These in turn are surrounded by a second layer of characters, namely 穴 (cave; 5 strokes) on the top and 辶 (walk; 4 strokes[a]) curving around the left and bottom.

Computer entry and phonetic substitution

[edit]Both the traditional and simplified Chinese characters for biáng were encoded in Unicode, on 20 March 2020, for Unicode 13.0.0. The code point is U+30EDE for the traditional form (𰻞) and U+30EDD for the simplified form (𰻝).[4]

Until that point, there were no standardized ways of entering or representing them on computers. Both traditional and simplified forms had been submitted to the Ideographic Rapporteur Group for inclusion in CJK Unified Ideographs Extension G.[5] As the characters are not widely available on computers (and not supported by many fonts), images of the characters, phonetic substitutes like 彪彪面 (biāobiāomiàn) or 冰冰面 (bīngbīng miàn), as well as the pinyin, are often used instead.

The character is described by the following ideographic description sequences (IDSs):[6]

⿺辶⿱穴⿱⿲月⿱⿲幺言幺⿲長馬長刂心 (traditional)

⿺辶⿱穴⿱⿲月⿱⿲幺言幺⿲长马长刂心 (simplified)

In Adobe's Source Han Sans (prior to 2.002) and Source Han Serif font these IDS sequences do not display as IDS sequences, but display the actual glyphs for the character.[7][8]

Unicode

[edit]After an email discussion with Lee Collins, John Jenkins submitted an application of "![]() " in 2006.[9] However, its IDS was too long at the time[10] and "radical 心 (heart)" is missing from the character shape.[11]

" in 2006.[9] However, its IDS was too long at the time[10] and "radical 心 (heart)" is missing from the character shape.[11]

Ming Fan (范銘)[12] submitted an application to the Unicode Consortium. At WS 2015, the traditional character had a code of UTC-00791 and the code of its simplified character is UTC-01312.[13]

However, the evidence for this character does not fully match the character shape. For UTC-00791, "radical 刂 (knife)" has disappeared from the dictionary (which is used as evidence).[14] For UTC-01312, "radical 刂 (knife)" has become "radical 戈 (dagger-axe)" in the academic paper used as evidence.[15] Members of the Unicode Consortium supported the character shape.[16] In a possible April fools' joke, Toshiya Suzuki suggested adding a new block ("CJK Complex Ideographic Symbols"), setting "![]() " as a basic shape, unifying the variation and even admitting "

" as a basic shape, unifying the variation and even admitting "![]() " as a variant of the character.[17][18]

" as a variant of the character.[17][18]

The character's traditional and simplified forms were added to Unicode version 13.0 in March 2020 in the CJK Unified Ideographs Extension G block of the newly allocated Tertiary Ideographic Plane.[19] The corresponding Unicode characters are:

- Traditional: U+30EDE 𰻞

- Simplified: U+30EDD 𰻝

Mnemonics

[edit]

There are a number of mnemonics used by Shaanxi residents to aid recall of how the character is written.

One version runs as follows:

| Traditional Chinese |

Simplified Chinese |

Pinyin | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 一點上了天 | 一点上了天 | Yīdiǎn shàngle tiān | Apex (丶) rising up to the sky, |

| 黃河兩道彎 | 黄河两道弯 | Huáng Hé liǎng dào wān | Over Two bends (冖) by Yellow River's side. |

| 八字大張口 | 八字大张口 | Bāzì dà zhāngkǒu | Character "Eight"'s (八) opening wide, |

| 言字往進走 | 言字往进走 | Yán zì wǎng jìn zǒu | "Speech" (言) enters inside. |

| 你一扭 我一扭 | 你一扭 我一扭 | Nǐ yī niǔ, wǒ yī niǔ | You twist, I twist too, (幺 'tiny') |

| 你一長 我一長 | 你一长 我一长 | Nǐ yī zhǎng, wǒ yī zhǎng | you grow, I grow (長) with you, |

| 當中加個馬大王 | 当中加个马大王 | Dāngzhōng jiā gè mǎ dàwáng | Inside, a horse (馬) king will rule. |

| 心字底 | 心字底 | Xīn zì dǐ | "Heart" (心) down below, |

| 月字旁 | 月字旁 | Yuè zì páng | "Moon" (月) by the side, |

| 留個鈎搭掛麻糖 | 留个钩搭挂麻糖 | Liú ge gōu dā guà má tang | Leave a hook (刂 'knife') for Matang (Mahua, Fried Dough Twist) to hang low, |

| 坐着車車逛咸陽 | 坐着车车逛咸阳 | Zuòzhe chēchē guàng Xiányáng | On our carriage, to Xianyang we'll ride (radical: 辶 'walk'). |

Note that the first two lines probably refer to the character 宀 (roof), building it up systematically as a point and a line (river) with two bends.[improper synthesis?]

Origin of the character

[edit]

The origins of the biangbiang noodles and the character biáng are unclear. In one version of the story, the character biáng was invented by the Qin dynasty Premier Li Si. However, since the character is not found in the Kangxi Dictionary, it may have been created much later than the time of Li Si. Similar characters were found used by Tiandihui.

In the 2007 season of the TVB show The Web (一網打盡), the show's producers tried to find the origin of the character by contacting university professors, but they could not verify the Li Si story or the origin of the character. It was concluded that the character was invented by a noodle shop.[clarification needed]

A legend about a student fabricating a character for the noodle to get out of a biangbiang noodle bill also is a commonly believed hypothesis about the origin of the character.[20]

According to a China Daily article, the word "biang" is an onomatopoeia that actually refers to the sound made by the chef when he creates the noodles by pulling the dough and slapping it on the table.[21]

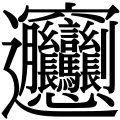

Variants

[edit]

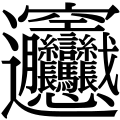

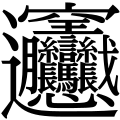

More than twenty variants of the Traditional character for biáng, having between 56 and 70[b] strokes:

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b The radical 辶 has only three strokes instead of four according to Mainland Chinese stroke order, so the traditional character is written with only 57 strokes there. This is reflected in the graphics of the Song style character and the stroke order animation to the right.

- ^ The radical 辶 has only three strokes instead of four according to Mainland Chinese stroke order, so the variant with 70 strokes is written with only 69 strokes there. This is reflected in the graphics of the characters below.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Zhang, Megan. "The Chinese noodle dish whose name doesn't exist". www.bbc.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "A Taste of Xi'an in North London". Fuchsia Dunlop. 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ Okrent, Arika (15 May 2013). "What is the Most Complex Chinese Character?". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ "CJK Unified Ideographs Extension G" (PDF). Unicode. 11 March 2020. p. 49⁄63. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ UTC Character Submission for 2015 Archived 13 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine by the Unicode Consortium

- ^ See Unicode Technical Report #45 Archived 13 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine and associated data File Archived 13 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine, UTC-00791. The file references this Wikipedia article as a primary source and a reason for inclusion.

- ^ Lunde, Ken (April 8, 2017), "Designing & Implementing Biáng", CJK Type Blog, Adobe, archived from the original on November 12, 2020, retrieved December 30, 2017

- ^ Lunde, Ken (November 19, 2018), Source Han Sans Version 2.000 (PDF), Adobe, archived (PDF) from the original on February 26, 2021, retrieved November 21, 2018

- ^ "John Jenkins: Proposed UTC C2 Submission. L2/06-364" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "Marnen Laibow-Koser: Re:Composition of not included Chinese characters".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pointed out by Satoshi Yamamoto, see CJK Ext. E 6.0. Editorial Group. IRG N1597.

- ^ Eiso Chan: My answer of "How to pronounce 'biáng'" at Zhihu Archived 28 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine,2016-12-30.

- ^ Unicode Consortium: IRG N2091R Archived 14 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 2 November 2015.

- ^ The character shape in the dictionary is

.

.

- ^ The character shape in the paper is

.

.

- ^ Japan Review on IRG Working Set 2015 ver 2.0 (IRGN2155: p.314-456) Archived 30 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 19 August 2016.

- ^ Toshiya Suzuki: Proposal to add new block "CJK Complex Ideographic Symbols" (WG2 N4796) Archived 15 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 1 April 2017

- ^ Chan, Eiso (4 May 2017). 现在我们是否需要一个新的表意文字区块? [Should We Need to Create a New Block for Ideographic Characters?]. 知乎专栏 知乎专栏 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ "CJK Unified Ideographs Extension G" (PDF). Unicode. 11 March 2020. p. 49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "The Hardest Chinese Character". China Simplified. 28 February 2014. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ Henderson, C. J.; Fan, Zhen (18 November 2012). "Biangbiang Shaanxi Street Food". ChinaDaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

External links

[edit]- (in Chinese) CCTV Forum Discussion on biáng Character

- (in Chinese) CCTV writeup on the ten strange wonders of Shaanxi

- Pictures of Chinese signs with biáng characters [1] [2]