Bethanie, Namibia

Bethanie

ǀUiǂgandes Klipfontein | |

|---|---|

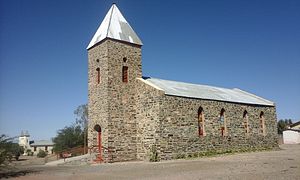

The Lentia Lutheran Church, built 1899. The village's mission church is in the background on the left. | |

| Coordinates: 26°30′00″S 17°09′30″E / 26.50000°S 17.15833°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | ǁKaras Region |

| Constituency | Berseba Constituency |

| Population (2023)[1] | |

• Total | 2,372 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (SAST) |

| Climate | BWh |

Bethanie (often in German: Bethanien, and in English: Bethany, previously Klipfontein, Khoekhoegowab: ǀUiǂgandes[2]) is a village in the ǁKaras Region of southern Namibia. It is one of the oldest settlements in the country.[3] Bethanie had 2,372 inhabitants in 2023.

Geography

[edit]Bethanie is situated on the C14 road between Goageb and Walvis Bay, 100 km (62 mi) west of Keetmanshoop.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 1,748 | — |

| 2023 | 2,372 | +2.58% |

| Source:[1] | ||

History

[edit]The area around Bethanie originally belonged to the Red Nation. At the beginning of the 18th century, the ǃAman (Bethanie Orlam), a subtribe of the Orlam people, obtained settlement rights and settled here.[4] As missionaries started travelling north from the Cape Colony in the early 19th century, they established mission stations on their way. The London Missionary Society founded the town, but, because of a shortage of missionaries and presumably because of the cooperation between the London and Rhenish Missionary Society at the time, they instead sent a German missionary.

Reverend Heinrich Schmelen arrived in 1814 as missionary of the Kaiǀkhauan (Khauas Nama) and their leader Amraal Lambert.[5] The Schmelenhaus was built the same year, long considered the oldest structure in Namibia. It has been a National Monument since 1952 and currently serves as a small museum. It was later discovered that the church and the pastor's house in Warmbad, both destroyed in 1811, were older than the Schmelenhaus,[6] and that the fortification of ǁKhauxaǃnas predates all other European constructions.[7] Schmelen also initiated the building of a chapel which was in ruins when James Edward Alexander visited the village in 1837.[8]

In 1822, Schmelen left Bethanie[9] after becoming frustrated with his missionary work among the local tribes, who refused his repeated and impassioned pleas to attend church[10] and because of an ongoing conflict between Amraal Lambert's Orlam and another Namaqua tribe living at the station. Livestock and men were killed, and buildings burned. According to James Edward Alexander, Schmelen had "tried in vain to prevent the people of the station exchanging their cattle at [Lüderitz] ... for fire-arms and ammunition" and saw no end to the local conflicts.[11]

The original church was built in 1859, and also still stands today.

In 1883, Bethanie was the scene of the historical land sale at the house of Namaqua chief Josef Frederiks II that would eventually establish Imperial Germany's colony of German South West Africa. Adolf Lüderitz in May 1883 obtained the area of Angra Pequena (today the town of Lüderitz) from Frederiks for 100£ in gold and 200 rifles. Three months later on 21 August, Frederiks sold Lüderitz with a stretch of land 140 kilometres (87 mi) wide, between the Orange River and Angra Pequena, for 500£ and 60 rifles.[12] This area was far bigger than Frederiks had thought, as the contract specified its width as "20 geographical miles", a term that the tribal chief was not familiar with: 1 German geographical mile was approximately 7.4 kilometres (4+5⁄8 mi), whereas the common mile in the territory was the English mile, 1.6 kilometres.[13]

Politics

[edit]Bethanie is governed by a village council that has five seats.[14]

In the 2004 local authority elections the Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA) narrowly won over South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) with 307 votes (three seats) to 299 (two seats).[15] In the 2010 local authority election Bethanie again was one of only a few local councils in Namibia that the SWAPO did not win. This time the Rally for Democracy and Progress (RDP, an opposition party founded in 2007) narrowly beat SWAPO with 253 to 245 votes. The DTA finished in 3rd with 52 votes.[16] The 2015 local authority election was won by SWAPO which gained three seats (278 votes) while the DTA gained the remaining two seats (188 votes).[17]

In the 2020 local authority election the Landless People's Movement (LPM, a new party registered in 2018) won with 378 votes and gained three seats. One seat each went to the Popular Democratic Movement (PDM, the new name of the DTA since 2017) with 179 votes, and to SWAPO with 166 votes.[18]

Bethanie is the seat of the !Aman Traditional Authority, and its current chief (Kaptein) is Johannes Frederick.[19][20] His predecessor David Frederick (Chief 1977-2018), alongside Herero Paramount Chief Advocate Vekuii Rukoro in January 2017 filed a class-action lawsuit against Germany on behalf of the Herero and Nama peoples in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.[21] David Frederick was the grandson of Cornelius Fredericks, a leading resistance fighter against German colonial invasion.[22]

Media and popular culture

[edit]A fictionalized version of Bethanie – named "Bethany" in English and depicted as a drought-plagued former mining town – is the primary setting for Richard Stanley's 1993 feature horror film, Dust Devil.

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b "4.5 Population by town and census years (2011 and 2023)" (PDF). Namibia 2023 - Population and Housing Census. Main Report. Namibia Statistics Agency. pp. 33–34. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ Vedder 1997, p. 198.

- ^ Tonchi, Lindeke & Grotpeter 2012, p. 40.

- ^ Dedering 1997, p. 58–59.

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, L". Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Warmbad becomes [sic] two hundred years". Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ Vogt, Andreas (2007). "Die ältesten Kirchen in Namibia (Teil 1)" [The oldest churches in Namibia, part 1]. Afrikanischer Heimatkalender 2007 (in German). Deutsche Evangelisch-Lutherische Kirche in Namibia (DELK).

- ^ Alexander 1967, p. 183.

- ^ Dedering 1997, p. 59–61.

- ^ "Bethanie, a village in Namibia". The cardboard box travel shop. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Alexander 1967, pp. 183–185.

- ^ "The man who bought a country". Namibia Guidebook. orusovo.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ Oermann, Nils Ole (1999). Mission, Church and State Relations in South West Africa Under German Rule (1884-1915). Missionsgeschichtliches Archiv. Vol. 5. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 58–60. ISBN 9783515075787.

- ^ "Know Your Local Authority". Election Watch. No. 3. Institute for Public Policy Research. 2015. p. 4.

- ^ "14 May 2004 Local Authority Elections in Namibia". African Elections Database. 31 December 2005. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Local Authority results Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Electoral Commission of Namibia

- ^ "Local elections results". Electoral Commission of Namibia. 28 November 2015. p. 3. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "2020 Local Authority Elections Results and Allocation of Seats" (PDF). Electoral Commission of Namibia. 29 November 2020. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Johannes Frederick elected as Chief of the !Aman Traditional Authority | nbc". nbcnews.na. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Tribute to Chief David Frederick". Truth, for its own sake. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Three vie for !Aman Traditional Authority chieftainship". Truth, for its own sake. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Tribute – chief David Frederick (1932-2018)". The Namibian. 2018-01-25. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

Literature

[edit]- Vedder, Heinrich (1997). Das alte Südwestafrika. Südwestafrikas Geschichte bis zum Tode Mahareros 1890 [The old South West Africa. South West Africa's history until Maharero's death 1890] (in German) (7th ed.). Windhoek: Namibia Scientific Society. ISBN 0-949995-33-9.

- Alexander, James Edward (1967) [1838]. Expedition of discovery into the interior of Africa : Through the Hitherto Undescribed Countries of the Great Namaquas, Boschmans, and Hill Damaras, Performed under the Auspices of Her Majesty's Government and the Royal Geographic Society. Africana Collectanea. Vol. 1. C. Struik, Cape Town. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- Dedering, Tilman (1997). Hate the old and follow the new: Khoekhoe and missionaries in early nineteenth-century Namibia. Vol. 2 (Missionsgeschichtliches Archiv ed.). Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-06872-7. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- Tonchi, Victor L; Lindeke, William A; Grotpeter, John J (2012). Historical Dictionary of Namibia. Historical Dictionaries of Africa, African historical dictionaries (2 ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810879904.