Battle off Texel

| Battle off Texel | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First World War | |||||||

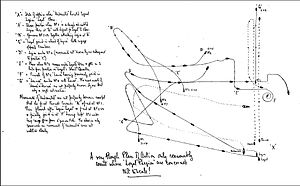

A sketch of the battle by one of the participants. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 light cruiser 4 destroyers | 4 torpedo boats[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5 wounded 3 destroyers lightly damaged |

218 killed 31 captured[3] 4 torpedo boats sunk | ||||||

The battle location in the North Sea | |||||||

The Battle off Texel, also known as the Action off Texel or the Action of 17 October 1914, was a naval battle off the coast of the Dutch island of Texel during the First World War. A British squadron, comprising one light cruiser and four destroyers on a routine patrol, encountered the German 7th Half Flotilla of torpedo boats which was en route to the British coast to lay mines.[4][a] The British forces attacked and the outgunned German force attempted to flee and then fought a desperate and ineffective action against the British force, which sank all four German boats.[5]

The battle resulted in the loss of the German torpedo boat squadron and prevented the mining of busy shipping lanes, such as the mouth of the River Thames. The British suffered few casualties and little damage to their vessels. The battle influenced the tactics and deployments of the remaining German torpedo boat flotillas in the North Sea area, as the loss shook the faith of their commanders in the effectiveness of the force.[6]

Background

[edit]After the opening naval Battle of Heligoland Bight, the German High Seas Fleet was ordered to avoid confrontations with larger opposing forces, to avoid costly and demoralising reverses. Apart from occasional German raids and forays by German light forces, the North Sea was dominated by the Royal Navy which regularly patrolled the area.[7] On 16 October 1914, information about the activities of German light forces in the Heligoland Bight became more definite and the 1st Division of the 3rd Destroyer Flotilla (Harwich Force), consisting of the new light cruiser HMS Undaunted (Captain Cecil Fox) and four Laforey-class destroyers, HMS Lennox, Lance, Loyal and Legion was sent to investigate. At 13:50 on 17 October, while steaming northwards, about 50 nmi (93 km; 58 mi) to the south-west of the island of Texel, the 1st Division encountered a squadron of German torpedo boats, comprising the remaining vessels of the 7th Half Flotilla (Korvettenkapitän Georg Thiele in S119) SMS S115, S117, S118 about 8 nmi (15 km; 9.2 mi) ahead.[b] The German ships were sailing abreast, about 0.5 nmi (0.93 km; 0.58 mi) apart, on a bearing slightly to the east of the 1st Division. The German ships made no hostile move against the British and made no attempt to flee; the British assuming that they had mistaken the ships for friendly vessels. The German flotilla was part of the Emden Patrol and had been sent out of the Ems River, to mine the southern coast of Britain including the mouth of the Thames but had been intercepted before reaching its objective.[8]

The British squadron out-gunned the German 7th Half Flotilla. Undaunted—an Arethusa-class light cruiser—was armed with two BL 6 inch Mk XII naval guns and seven QF 4 inch Mk V naval guns, in single mounts (most without gun shields) and eight torpedo tubes. Undaunted was experimentally armed with a pair of 2-pounder anti-aircraft guns, something most of her class lacked and at best speed could make 28.5 kn (52.8 km/h; 32.8 mph). The four Laforey-class destroyers were armed with four torpedo tubes in two twin mounts, three 4-inch guns and a 2-pounder gun. The destroyers were slightly faster than the cruiser and could make about 29 kn (54 km/h; 33 mph) at full power.[9] The German boats were nearly equal in speed to the British at 28 kn (52 km/h; 32 mph).[10] They were inferior to the British in other areas: the 7th Half Flotilla was composed of ageing Großes Torpedoboot 1898 class boats and had been completed in 1904. Each of the German vessels was armed with three 50 mm (1.97 in) guns, that were of shorter range and throw-weight than the British guns. The biggest danger to the British squadron was the five 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedoes carried by each German boat.[11]

Battle

[edit]

Upon closer approach, the German vessels realised the nearby vessels were British and scattered, while Undaunted—which was closer to the Germans than the destroyers—opened fire on the nearest torpedo boat. This German vessel managed to dodge the fire from Undaunted but lost speed and the British force caught up. To protect Undaunted from torpedo attack and to destroy the Germans as quickly as possible, Fox ordered the squadron to divide. Lance and Lennox chased S115 and S119 as Legion and Loyal pursued S117 and S118.[5] Fire from Legion, Loyal and Undaunted damaged S118 so badly that its bridge was blown off the deck, sinking her at 15:17. Lance and Lennox engaged S115, disabling her steering gear and causing the German vessel to circle. Lennox's fire was so effective that the bridge of S115 was also destroyed but the German torpedo-boat did not strike her colours.[12]

The two central boats in the German flotilla, S117 and the flotilla leader S119, tried to torpedo Undaunted but it outmanoeuvred the German boats and remained unscathed.[12] When Legion and Loyal had finished off S118, they came to Undaunted's aid and engaged the two attackers. Legion attacked S117, which fired its last three torpedoes and continued to engage with gunfire. Legion pulverised S117, damaging her steering mechanism which forced her to circle before she was sunk at 15:30. At the same time, Lance and Lennox had damaged S115 to the point where only one of the destroyers was needed. Lance joined Loyal in bombarding S119 with lyddite shells.[5] S119 managed to fire a torpedo at Lance and hit the destroyer amidships but the torpedo failed to detonate. S119 was sunk at 15:35 by gunfire from Lance and Loyal, taking the German flotilla commander with it. S115 stayed afloat despite constant attacks from Lennox, which sent a boarding party, who found a wreck with only one German on board who happily surrendered. Thirty members of the crew were eventually rescued from the sea by the British vessels.[10] The action ended at 16:30, with gunfire from Undaunted finishing off the abandoned hulk of S115.[5]

Aftermath

[edit]Analysis

[edit]

The battle was seen as a boost of morale for the British as two days previous, they had lost the cruiser HMS Hawke to a U-boat. The effect on British morale is reflected in its inclusion in the 1915 novel The Boy Allies Under Two Flags, written by Robert L. Drake.[13] The hospital ship Ophelia, which had been sent out to rescue survivors from the sunken boats, was seized by the British for violating the Hague Convention rules on the use of hospital ships.[14] The loss of a squadron of German torpedo boats led to a drastic change in tactics in the English Channel and along the coast of Flanders. There were fewer sorties into the Channel and the torpedo boat force was relegated to coastal patrol and rescuing aircrew.[15] The British received a bonus on 30 November, when a trawler pulled up the sealed chest thrown off S119 by Captain Thiele. The chest contained a codebook used by the German light forces stationed on the coast, allowing the British to read German wireless communication for a long time afterwards.[8]

Casualties

[edit]Despite the odds, no German vessel struck her colours and the flotilla fought to the end. The four ships of the German Seventh Half Flotilla were sunk by Harwich Force and over two hundred sailors were killed, including the commanding officer. Thirty-one German sailors were rescued and taken prisoner; a captured officer died of wounds soon after.[3] Two more German sailors were later rescued by a neutral vessel.[13] Only four British sailors were wounded and three of their destroyers were lightly damaged.[3] Legion had one 4 lb (1.8 kg) shell hit and one man was wounded by machine-gun fire. Loyal was hit twice and had three or four men wounded. Lance had superficial machine-gun damage and the other vessels were unscathed.[13]

Order of battle

[edit]Royal Navy

[edit]3rd Destroyer Flotilla (detachment), Captain Cecil H. Fox, Captain (D)

- HMS Undaunted, light cruiser acting as flotilla leader

1st division, 3rd Destroyer Flotilla

- HMS Lance, destroyer; Commander Wion de M. Egerton, division commander[3]

- HMS Lennox, destroyer; Lieutenant-Commander Clement. R. Dane, commander[3]

- HMS Legion, destroyer; Lieutenant-Commander Claud F. Allsup, commander[3]

- HMS Loyal, destroyer; Lieutenant-Commander Burges Watson, commander[3]

German Navy

[edit]7th Torpedoboat Half-flotilla, Korvettenkapitän Georg Thiele †, commander

- SMS S119, torpedo boat, flagship; Oberleutnant zur See Wilhelm Windel †, commander[16]

- SMS S118, torpedo boat; Kapitänleutnant Erich Beckert †, commander[16]

- SMS S117, torpedo boat; Kapitänleutnant Georg Sohnke †, commander[16]

- SMS S115, torpedo boat; Kapitänleutnant Hans Mushacke †, commander[16]

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Williamson 2003, p. 9.

- ^ Halsey 1920, p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Corbett 2009, p. 218.

- ^ Scheer 1920, p. 60.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d NRV 1919, pp. 140–145.

- ^ Karau 2003, pp. 44–58.

- ^ Osborne 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Halpern 1995, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Parkes 1919, pp. 1–634.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wyllie 1918, p. 30.

- ^ Groner 1990, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wyllie 1918, p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Drake 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Scheer 1920, p. 61.

- ^ Karau 2003, pp. 54–58.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Toeche-Mittler 1922.

References

[edit]Books

- Corbett, J. S. (2009) [1938]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War based on Official Documents. Vol. I (2nd rev. Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press repr. ed.). London: Longmans, Green. ISBN 978-1-84342-489-5. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Drake, R. L. (2004) [1915]. The Boy Allies Under Two Flags (Gutenburg ed.). New York: A. L. Burt. OCLC 746986968. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Groner, E. (1990). German Warships 1815–1945: Major Surface Vessels. Vol. I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 169–171. ISBN 0-87021-790-9.

- Halpern, P. G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, MD: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Halsey, F. (1920). The Literary Digest History of the World War: Compiled from Original and Contemporary Sources: American, British, French, German, and Others. Vol. X. New York and London: Funk and Wagnalls. OCLC 312834. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- Karau, M. (2003). Wielding the Dagger. Westport, CN: Praeger. ISBN 0-313-32475-1.

- Osborne, E. (2004). Cruisers and Battle Cruisers: An Illustrated History of Their Impact (Weapons and Warfare). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-369-9.

- Parkes, O. (1919). Jane's Fighting Ships. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. OCLC 867861890.

- Scheer, R. (1920). Germany's High Sea Fleet in the World War. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne: Cassell. pp. 60–62. OCLC 2765294. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Williamson, G. (2003). German Destroyers 1939–45. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-504-X.

- Wyllie, W. L. (1918). Sea Fights of the Great War: Naval Incidents of the First Nine Months. London: The Naval Society. OCLC 2177843. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

Journals

- "Action on October 17th, 1914, between the Undaunted, Legion, Loyal, Lance and Lennox and four German T. B. D's. of S. Class" (PDF). The Naval Review. V. London: The Naval Society. 1919. OCLC 9030883. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

Websites

- Toeche-Mittler, S. (1922). "Half Mast the Flag! Honor Roll of Fallen and Died in the Great War 1914–1918 Naval Officers and Fähnriche z. S., Officers and Sailors Artillery and Marines along with Fähnrichen, the Naval Engineers along with Aspirants, the Navy Medical Officers, Navy Zahlmeister, Fire Plant and Torpeder Officers and Navy Officials" (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler. OCLC 16875659. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- "British Victory at Sea". New York Times. New York. 18 October 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 April 2010.