Battle of Hucisko

| Battle of Hucisko | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Henryk Dobrzański |

Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger Fritz Katzmann | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| about 100 soldiers | several hundred policemen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

11 killed 2 missing 10 wounded 1 deserter |

about 100 killed and wounded 6 destroyed vehicles | ||||||

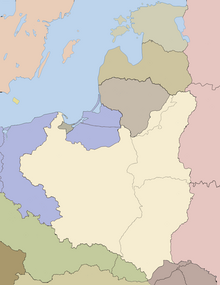

Location within occupied Poland (1939–1941) | |||||||

The Battle of Hucisko was a confrontation between the Detached Unit of the Polish Army led by Major Henryk Dobrzański, codenamed Hubal, and the 51st Battalion of the German Ordnungspolizei, fought on 30 March 1940, near the village of Hucisko in the Kielce Land.

The battle lasted for over two hours. Despite the enemy's numerical and technical superiority, the Polish soldiers forced the Germans to retreat and inflicted heavy casualties. The battle at Hucisko was the first major victory for Hubal's men and the first significant partisan engagement of World War II. In retaliation for the defeat, the Germans twice pacified Hucisko and committed numerous atrocities in neighbouring villages.

Origins

[edit]

The origins of Hubal's unit date back to the last days of the September Campaign. In late September 1939, Major Henryk Dobrzański, of the 110th Reserve Uhlan Regiment, gathered a group of officers and soldiers around him, all determined to continue fighting the Germans.[1] Initially, Dobrzański planned to come to the aid of the besieged Warsaw, but upon receiving news of its surrender, he decided to try to break through to Hungary and from there reach the Polish Army being reformed in France. A similar plan was shared by several of his subordinates.[2] In the early days of October 1939, the group made its way to the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, where the enthusiastic reception from the local population convinced Dobrzański that the September defeat had not broken the resolve of the Polish society. The idea of marching to Hungary was abandoned in favour of continuing the fight against the occupiers within the country. Soon after, Major Dobrzański adopted the codename Hubal.[3] By February 1940, his unit had taken the name of the Detached Unit of the Polish Army.[4]

The area of operation for Hubal's unit became the region of Kielce. Major Dobrzański aimed to wait for the expected Franco-British offensive in the spring of 1940 and to support the Allies with intense military actions behind German lines.[5] He also tried to create a covert military organisation, Okręg Bojowy Kielce, which would provide logistical support for his unit, organise the local population, and prepare for a future armed uprising.[6] By the first decade of March 1940, there were already 320 soldiers in Hubal's ranks.[7] Hubal gained great popularity and authority among the local population,[8] and his actions contributed to overcoming the apathy and discouragement prevalent in Polish society at the time.[9]

However, by mid-March 1940, the leadership of the Union of Armed Struggle, which had a radically different approach to the struggle against the occupier, attempted to dissolve Hubal's unit. On the orders of the commander of the Łódź District of the Union of Armed Struggle, Colonel Leopold Okulicki, codenamed Miller, a significant number of officers and soldiers left the unit on 13 March.[10] Major Dobrzański, determined to continue the open fight, was left with 70 soldiers. That same evening, the reduced unit left their previous quarters in the village of Gałki and moved to the village of Hucisko, where they stayed for over two weeks.[11] Thanks to the influx of volunteers, the unit's size soon grew to over 100 soldiers.[12]

Although Major Dobrzański sought to avoid major confrontations with the Germans, the mere existence of his unit caused concern among the occupiers, especially with the anticipated outbreak of fighting on the Western Front. In March 1940, the Germans began preparations to deal with Hubal, but disputes over jurisdiction between the Wehrmacht and the police authorities of the General Government delayed the start of the operation.[13]

First skirmishes

[edit]On 30 March 1940, SS and Ordnungspolizei concentrated around Skarżysko-Kamienna, Szydłowiec, Chlewiska, and Przysucha began a manhunt for Hubal's unit. The scale of this operation is demonstrated by the fact that approximately 5,000 SS and Ordnungspolizei officers participated,[14] led personally by the SS and Police Leader in the General Government (HSSPF "Ost"), SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger.[15] Due to the fact that the police authorities did not want to share their expected success with anyone,[16] the plan and the timing of the operation were kept secret from the local Wehrmacht commanders.[14]

The German intelligence did not have precise information on the whereabouts of Hubal's unit, so the occupiers decided to attack both villages they knew to be its headquarters – Gałki and Hucisko. This strike was carried out by two battalions of the Ordnungspolizei under the overall command of SS-Oberführer Fritz Katzmann.[17] The unit tasked with capturing Hucisko was the 51st Police Battalion.[18]

Both German battalions took their positions on 29 March and began their offensive operations at dawn the following day.[19] The first skirmish occurred during the night of 29 to 30 March, when the forward security of the 51st Battalion was fired upon by a Polish sentry shortly after exiting Chlewiska. Shortly afterward, a four-man Polish patrol led by Lieutenant Adolf Bączewski was attacked by the Germans near Stefanków.[a] Bączewski engaged in an unequal battle with the entire German company, intending to delay the enemy's march and give Hubal additional time to prepare for defence. One of Hubal's soldiers was killed in the skirmish, and two others were severely wounded. The Germans also suffered losses, including the wounding of the commander of the 4th Company of the 51st Battalion.[18]

Initially, the reports about the German movements did not cause concerns for Major Hubal, who predicted that the enemy would not launch a full-scale attack before dawn. Nevertheless, the major sent a strong patrol toward Stefanków to conduct reconnaissance and evacuate the wounded.[20] At dawn, the patrol engaged in a skirmish with superior German forces, resulting in a retreat toward Skłoby. Only two wounded soldiers managed to return to the main forces.[20]

At the same time, while the 51st Battalion was moving toward Hucisko, the second German battalion occupied the undefended Gałki. The police arrested 40 men in the village, who were taken to a prison in Radom.[b][19]

Battle of Hucisko

[edit]In the early morning, Hubal ordered combat readiness, but the defensive positions were only occupied after patrols confirmed that the Germans had taken Skłoby and that there was no threat to the Polish rear from the road between Końskie and Przysucha.[21] The defence plan anticipated that the main German assault would fall on two 30-man infantry platoons, stationed at the edge of the forest about two kilometres from Hucisko. The left wing was defended by the 1st Platoon, commanded by Platoon Leader Antoni Kisielewski, while the right wing was held by the 2nd Platoon, led by Platoon Leader Antoni Bilski. In reserve, Hubal left a cavalry platoon under the command of Sergeant Major Józef Alicki and a team of heavy machine guns. The Polish defence line was spread out, with shooters stationed roughly every 10 meters. In their favour, the infantry had as many as 14 light machine guns.[22]

The German assault began around 11:00 AM. The Polish infantry allowed the enemy to approach to about 60–80 meters, then opened heavy fire with handguns and machine guns. The gunfire caused confusion and heavy losses in the German ranks, but the policemen quickly recovered from the surprise and responded with dense, though inaccurate, fire. At one point, the Germans even managed to push part of the 2nd Platoon from their positions. Hubal then sent 10 infantrymen from the left wing to restore the situation, which allowed the original positions to be regained.[23] The major also sent a three-man mounted patrol to the left wing's edge, led by Corporal Brzozowski, ordering them to bypass the Germans from the northeast and then fire on their flank. This action caused temporary confusion in the German ranks and reduced the pressure on the 1st Platoon. Encouraged by the success, Brzozowski continued his raid into the German rear but fell into an ambush and was killed, with two of his subordinates wounded (both managed to return to the main forces of the unit).[24]

Meanwhile, another patrol was sent south and confirmed that no attack was coming from that direction. This information allowed Hubal to freely deploy the unused reserve. Cavalry patrols also observed a poorly guarded column of German vehicles on the unfinished road between Skłoby and Hucisko.[25] Upon hearing this, Hubal ordered Sergeant Major Alicki to bypass the German positions under the cover of the forest and then destroy the unprotected vehicles. The surprise raid was completely successful. The cavalrymen either eliminated or forced the Germans near the vehicles to flee, then proceeded to set fire to the abandoned vehicles.[25] When a German passenger car approached from the direction of Skłoby, the Poles threw grenades at it and killed the resisting crew.[c][25]

The sounds of the battle in the rear caused confusion in the German ranks. The policemen halted their assault and began to retreat. This situation was exploited by Platoon Leader Kisielewski, who led his platoon into a bayonet charge, forcing the Germans to flee.[26] The 2nd Platoon advanced less decisively, allowing the German company fighting on its section to retreat in relative order. Their manoeuvres threatened to cut off Alicki's platoon, which had already run out of ammunition. The cavalrymen had to retreat from the road before they could destroy all the vehicles.[26]

The battle lasted more than two hours. The defeated German battalion retreated toward Chlewiska. A patrol sent to follow them, commanded by Sergeant Major Romuald Rodziewicz, was unable to make contact with the enemy.[27]

Balance

[edit]The Battle of Hucisko was the first major victory for Hubal's unit and the first significant partisan battle fought during World War II.[27] Despite the enemy's numerical and technical superiority, the Polish soldiers forced the Germans to retreat and inflicted heavy losses, with around 100 killed and wounded. Hubal's unit also destroyed six German vehicles, including four trucks, and damaged several others.[27]

The Detached Unit of the Polish Army suffered smaller, but still significant, losses. 11 men were killed, two were missing, 10 were wounded, and one deserted.[d][27]

After the battle, Hubal promoted several soldiers in recognition of their contributions, including Franciszek Głowacz to the rank of corporal and Marianna Cel to the rank of senior lancer.[28]

Aftermath

[edit]Despite the victory, Hubal realised that his unit would not be able to withstand the main forces of the German encirclement. Additionally, he considered the start of regular battles with the Germans premature and still intended to preserve his unit until the anticipated Allied offensive. For these reasons, he decided to begin a retreat to the Świętokrzyskie Mountains.[29]

On the evening of 30 March, the Polish soldiers left Hucisko, and after a 25-kilometer march, they reached the village of Szałas the following morning.[30] On 1 April, the Germans launched another attempt to destroy the unit, but Hubal's unit managed to repel the attack and break away from the enemy.[31] The major then directed his unit eastward, but an attempt to cross the road between Skarżysko-Kamienna and Kielce failed. At this point, he decided to turn back westward, splitting the unit into two parts. On the night of 1 to 2 April, a cavalry detachment, with Hubal at its head, broke through the positions of the 8th SS-Totenkopfverbände Regiment, stationed along the road between Odrowąż and Samsonów. The cavalry then hid for the entire day in a dense thicket, and after nightfall, they moved toward Podchyby, where they silently crossed the outer ring of the German blockade.[32] However, a detachment of infantry, commanded by 2nd Lieutenant Marek Szymański, codenamed Sęp, was unable to break through the German cordon. He had to allow his soldiers to leave the encirclement individually.[33]

Hubal waited in vain for the infantrymen in the village of Kamienna Wola for two days, then resumed the retreat southwestward.[34] Soon after, his unit, now reduced to 23 men, took quarters in the village of Mały Węgrzyn.[35] Having lost contact with Hubal's unit, the Germans announced on 2 April the end of the operation and the defeat of the Polish unit[36] (a claim later refuted by Hubal in a proclamation to the Polish population).[37]

In retaliation for their failure, the Germans launched a large-scale pacification campaign targeting villages near which Hubal's unit had operated.[38] Between 30 March and 11 April 31 towns in the pre-war counties of Końskie, Kielce, and Opoczno were affected by various forms of repression. Four villages were completely burned down, and a large part of the buildings in a fifth village was destroyed. The Germans murdered 712 civilians, including two women and six children.[39]

Hucisko was pacified twice. On 31 March, the Germans arrested 33 men, most of whom were later deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.[40] On 11 April, a German punitive expedition completely burned down the village and executed 22 men.[41] As a result of both pacifications, a total of 43 inhabitants of Hucisko were killed.[42]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The patrol was returning from Wandów after completing a supply mission (Kosztyła (1987, p. 174)).

- ^ All 40 were executed on 4 April 1940, at Firlej near Radom. A total of 145 men arrested during the raid on Hubal's unit were killed in this execution (Terror hitlerowski (1988, pp. 23, 41)).

- ^ Only the passenger dressed in a Polish military uniform survived. He managed to convince the cavalrymen that he was a volunteer who had been arrested by the Germans while on his way to join Hubal's unit. It was only later revealed that the man was a German agent (Kosztyła (1987, p. 179)).

- ^ These calculations also include the losses incurred by the Polish unit during the skirmishes leading up to the actual battle (Kosztyła (1987, p. 180)).

References

[edit]- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 44–46)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 46–51)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 82–84)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 135)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 84)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 85, 92–95)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 149)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 132)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 242)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 154–160)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 158)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 163)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 151–153)

- ^ a b Kosztyła (1987, p. 172)

- ^ Terror hitlerowski (1988, pp. 40, 46)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 153)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 172–173)

- ^ a b Kosztyła (1987, p. 174)

- ^ a b Kosztyła (1987, p. 173)

- ^ a b Kosztyła (1987, pp. 174–175)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 175)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 175–176)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 176)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 176–177)

- ^ a b c Kosztyła (1987, pp. 177–179)

- ^ a b Kosztyła (1987, pp. 179–180)

- ^ a b c d Kosztyła (1987, p. 180)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 181)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 180–181)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 182)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 185–191)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 192–196)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 196–200)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 196, 200)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 200, 207)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 200)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, p. 207)

- ^ Kosztyła (1987, pp. 202–203)

- ^ Terror hitlerowski (1988, pp. 13, 44–45)

- ^ Terror hitlerowski (1988, pp. 41, 44)

- ^ Terror hitlerowski (1988, pp. 23, 43)

- ^ Terror hitlerowski (1988, p. 45)

Bibliography

[edit]- Kosztyła, Zygmunt (1987). Oddział Wydzielony Wojska Polskiego Majora "Hubala" [Detached Unit of the Polish Army of Major "Hubal"] (in Polish). Warsaw: MON. ISBN 83-11-07345-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - "Terror hitlerowski na wsi kieleckiej. Wybór dokumentów źródłowych" [Hitlerite Terror in the Kielce Countryside: A Selection of Source Documents]. Rocznik Świętokrzyski (in Polish). XV. 1988. ISSN 0485-3261.