Basque–Icelandic pidgin

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (March 2021) |

| Basque–Icelandic pidgin | |

|---|---|

| Region | Iceland, Atlantic |

| Ethnicity | Basques, Icelanders |

| Era | 17th century |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

qbi | |

| Glottolog | icel1248 Icelandic–Basque Pidginbasq1251 Basque Nautical Pidgin |

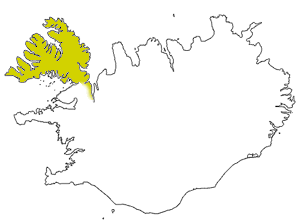

Westfjords, the Icelandic region that produced the manuscript containing the Basque–Icelandic pidgin | |

The Basque–Icelandic pidgin (Basque: Euskoislandiera, Islandiera-euskara pidgina; Icelandic: Basknesk-íslenskt blendingsmál) was a Basque-based pidgin spoken in Iceland during the 17th century. It consisted of Basque, Germanic, and Romance words.

Basque whale hunters who sailed to the Icelandic Westfjords used the pidgin as a means of rudimentary communication with locals.[1] It might have developed in Westfjords, where manuscripts were written in the language, but since it had influences from many other European languages, it is more likely that it was created elsewhere and brought to Iceland by Basque sailors.[2] Basque entries are mixed with words from Dutch, English, French, German and Spanish. The Basque–Icelandic pidgin is therefore not a mixture of Basque and Icelandic, but between Basque and other languages. It was so named because it was written in Iceland and translated into Icelandic.[3]

Only a few manuscripts have been found containing Basque–Icelandic glossary, and knowledge of the pidgin is limited.

Basque whalers in Iceland

[edit]Basque whalers were among the first to catch whales commercially; they spread to the far parts of the North Atlantic and even reached Brazil. They started coming to Iceland about 1600.[4] In 1615, after becoming shipwrecked and getting into a conflict with the locals, some Basque sailors were massacred in an event that would be known as the Slaying of the Spaniards. Basques continued to sail to Iceland, but for the second half of the 17th century French and Spanish whalers are more often mentioned in Icelandic sources.[4]

History of the glossaries

[edit]Only a few anonymous glossaries have been found. Two of them were found among the documents of 18th century scholar Jón Ólafsson of Grunnavík, titled:

- Vocabula Gallica ("French words"). Written during the latter part of the 17th century, a total of 16 pages containing 517 words and short sentences, and 46 numerals.[5][6]

- Vocabula Biscaica ("Biscayan (Basque) words"). A copy written during the 18th century by Jón Ólafsson, the original is lost. It contains a total of 229 words and short sentences, and 49 numerals. This glossary contains several pidgin words and phrases.[1][7]

These manuscripts were found in the mid-1920s by the Icelandic philologist Jón Helgason in the Arnamagnæan Collection at the University of Copenhagen. He copied the glossaries, translated the Icelandic words into German and sent the copies to professor C. C. Uhlenbeck at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Uhlenbeck had expertise in Basque, but since he retired from the university in 1926, he gave the glossaries to his post-graduate student Nicolaas Gerard Hendrik Deen. Deen consulted with the Basque scholar Julio de Urquijo, and in 1937, Deen published his doctoral thesis on the Basque–Icelandic glossaries. It was titled Glossaria duo vasco-islandica and written in Latin, though most of the phrases of the glossaries were also translated into German and Spanish.[2]

In 1986 Jón Ólafsson's manuscripts were brought back from Denmark to Iceland.[8]

The manuscript with the glossaries (University of Iceland):[9]

There is also evidence of a third contemporary Basque–Icelandic glossary. In a letter, the Icelandic linguist Sveinbjörn Egilsson mentioned a document with two pages containing "funny words and glosses"[a][10] and he copied eleven examples of them. The glossary itself has been lost, but the letter is still preserved at the National Library of Iceland. There is no pidgin element in the examples he copies.[2]

The fourth glossary

[edit]A fourth Basque–Icelandic glossary was found at the Houghton Library at Harvard University. It had been collected by the German historian Konrad von Maurer when he visited Iceland in 1858, the manuscript is from the late 18th century or the early 19th century.[11] The glossary was discovered around 2008,[12] the original owner had not identified the manuscript as containing Basque text.[13] Only two of the pages contain Basque–Icelandic glossary; the material surrounding includes unrelated items such as instructions about magic and casting love spells. It is clear that the copyist was not aware that they were copying Basque glossary, as the text has the heading "A few Latin glosses".[11] Many of the entries are corrupted or wrong, seemingly made by someone not used to writing. A large number of the entries are not a part of Deen's glossary, and so the manuscript is thought to be a copy of an unknown Basque–Icelandic glossary. A total of 68 words and phrases can be discerned, but with some uncertainty.[11]

Pidgin phrases

[edit]The manuscript Vocabula Biscaica contains the following phrases which contain a pidgin element:[14]

| Basque glossary | Modern Basque[15][better source needed][circular reference][clarification needed] | Icelandic glossary | Standard Icelandic orthography | English translation[b] | Word number[c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presenta for mi | Emaidazu | Giefdu mier | Gefðu mér | Give me | 193 & 225 |

| Bocata for mi attora | Garbitu iezaidazu atorra | Þvodu fyrer mig skyrtu | Þvoðu fyrir mig skyrtu | Wash a shirt for me | 196 |

| Fenicha for ju | Izorra hadi! | Liggia þig | Liggja þig | Fuck you![d] | 209 |

| Presenta for mi locaria | Emaizkidazu lokarriak | Giefdu mier socka bond | Gefðu mér sokkabönd | Give me garters | 216 |

| Ser ju presenta for mi | Zer emango didazu? | Hvad gefur þu mier | Hvað gefur þú mér? | What do you give me? | 217 |

| For mi presenta for ju biskusa eta sagarduna | Bizkotxoa eta sagardoa emango dizkizut | Eg skal gefa þier braudkoku og Syrdryck | Ég skal gefa þér brauðköku og súrdrykk | I will give you a biscuit and a sour drink[e] | 218 |

| Trucka cammisola | Jertse bat erosi | Kaufftu peisu | Kauptu peysu | Buy a sweater | 219 |

| Sumbatt galsardia for | Zenbat galtzerdietarako? | Fyrer hvad marga socka | Fyrir hvað marga sokka? | For how many socks? | 220 |

| Cavinit trucka for mi | Ez dut ezer erosiko | Eckert kaupe eg | Ekkert kaupi ég | I buy nothing | 223 |

| Christ Maria presenta for mi Balia, for mi, presenta for ju bustana | Kristok eta Mariak balea ematen badidate, buztana emango dizut | Gefe Christur og Maria mier hval, skal jeg gefa þier spordenn | Gefi Kristur og María mér hval, skal ég gefa þér sporðinn | If Christ and Mary give me a whale, I will give you the tail | 224 |

| For ju mala gissuna | Gizon gaiztoa zara | Þu ert vondur madur | Þú ert vondur maður | You are an evil man | 226 |

| Presenta for mi berrua usnia eta berria bura | Emadazu esne beroa eta gurin berria | Gefdu mier heita miölk og nyt smior | Gefðu mér heita mjólk og nýtt smjör | Give me hot milk and new butter | 227 |

| Ser travala for ju | Zertan egiten duzu lan? | Hvað gjörir þú? | What do you do? | 228 |

A majority of these words are of Basque origin:

- atorra, atorra 'shirt'

- balia, balea 'baleen whale'

- berria, berria 'new'

- berrua, beroa 'warm'

- biskusa, (Lapurdian) loan word bizkoxa 'biscuit', nowadays meaning gâteau Basque (cf. Spanish bizcocho, ultimately from Medieval Latin biscoctus)

- bocata[f]

- bustana, buztana 'tail'

- eta, eta 'and'

- galsardia, galtzerdia 'the sock'

- gissuna, gizona 'the man'

- locaria, lokarria 'the tie/lace(s)'

- sagarduna, sagardoa 'the cider'

- ser, zer 'what'

- sumbatt, zenbat 'how many'

- travala, old Basque trabaillatu, related to French and Spanish trabajar 'to work'

- usnia, esnea 'the milk'

- bura, 'butter', from Basque Lapurdian loan word burra[g] (cf. French beurre, Italian burro and Occitan burre)

Some of the words are of Germanic origin:

- cavinit, old Dutch equivalent of modern German gar nichts 'nothing at all'[10] or Low German kein bit niet 'not a bit'[20]

- for in the sentence sumbatt galsardia for could be derived from many different Germanic languages[21]

- for mi, English 'for me' (used both as subject and object; 'I' and 'me') or Low German 'för mi'

- for ju, English 'for you' (used both as subject and object) or Low German 'för ju'

And others come from the Romance languages:

- cammisola, Spanish camisola 'shirt'

- fenicha, Spanish fornicar 'to fornicate'

- mala, French or Spanish mal 'bad' or 'evil'

- trucka, Spanish trocar 'to exchange'[h]

All nouns and adjectives in the pidgin are marked with Basque's definite article suffix -a, even in cases for which the suffix would be ungrammatical in Basque. The order of nouns and adjectives is also reversed. For example, pidgin berrua usnia ('warm milk-DET') versus Basque esne beroa ('milk warm-DET').[22]

Although there are quite a few Spanish and French words listed in the glossaries, this is not a sign of the pidgin language, but rather a result of French and Spanish influence on the Basque language throughout the ages, since Basque has taken many loan words from its neighbouring languages.[20] Furthermore, many of the people in the Basque crews that came to Iceland might have been multilingual, speaking French and/or Spanish as well. That would explain for example why the Icelandic ja 'yes' is translated with both Basque bai and French vÿ (modern spelling oui) at the end of Vocabula Biscaica.[23][24]

Other examples

[edit]These examples are from the recently discovered Harvard manuscript:[25]

| Basque glossary | Correct 17th century Basque | Icelandic glossary | Standard Icelandic orthography | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nola dai fussu | Nola deitzen zara zu? | hvad heitir þu | Hvað heitir þú? | What's your name? |

| Jndasu edam | Indazu eda-te-ra | gief mier ad drecka | Gef mér að drekka | Give me (something) to drink |

| Jndasu jaterra | Indazu ja-te-ra | gief mier ad eta | Gef mér að eta | Give me (something) to eat |

| Jndasunirj | Indazu niri | syndu mier | Sýndu mér | Show me |

| Huna Temin | Hunat jin | kom þu hingad | Kom þú hingað | Come here |

| Balja | Balea | hvalur | hvalur | A whale |

| Chatucumia | katakume[i] | kietlingur | kettlingur | A kitten |

| Bai | Bai | ja | já | Yes |

| Es | Ez | nei | nei | No |

The first phrase, nola dai fussu ("What's your name?"), might be written with standardized (but ungrammatical) Basque as "Nola deitu zu?".[26] That is a morphologically simplified construction of the correct Basque sentence "Nola deitzen zara zu?".[27]

A section in Vocabula Biscaica goes over a few obscenities:

| Basque glossary | Icelandic glossary | English translation | Word number[c] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sickutta Samaria | serda merina | go fuck a horse | 211 |

| gianzu caca | jettu skÿt | eat shit | 212 |

| caca hiarinsat | et þu skÿt ur rasse | eat shit from an asshole | 213 |

| jet sat | kuss þu ä rass | kiss [my] ass | 214 |

See also

[edit]- Algonquian–Basque pidgin, a Basque-based pidgin in Canada

- Russenorsk, a Russian–Norwegian pidgin

Notes

[edit]- ^ The two pages can be seen here.

- ^ Based on the Icelandic text, which differs in some places from the Basque equivalents.

- ^ a b In Jón Ólafsson's manuscript.

- ^ The phrases fenicha for ju - liggia þig were among the few entries in the glossaries that Deen did not translate to German or Spanish in his doctoral thesis. Instead he wrote cum te coire 'to sleep with you' in Latin.[16] However, Miglio believes that the phrase rather should be understood as an insult.[17]

- ^ The Basque word sagarduna means 'cider', but the Icelandic word syrdryck means 'sour drink'.

- ^ Deen suggests that bocata is bokhetatu with the Spanish translation colar 'sieve', 'percolate' or 'pass'. The Icelandic equivalent is þvodu 'wash!'.[18]

- ^ The loan word burra is documented in the Northern Basque Country Basque-language written tradition since the mid-17th century.[19]

- ^ Could also be derived from Basque trukea 'the exchange'.[16]

- ^ In modern Basque.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Miglio 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Guðmundsson 1979.

- ^ Bakker et al. 1991.

- ^ a b Edvardsson; Rafnsson (2006), Basque whaling around Iceland: archeological investigation in Strákatangi, Steingrímsfjörður (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2021, retrieved 8 March 2019

- ^ Miglio 2008, p. 1.

- ^ "AM 987 4to / Vocabula Gallica. Basque-Icelandic Glossary". Árnastofnun (in Icelandic). Árnastofnun / The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "AM 987 4to / Vocabula Biscaica. Basque-Icelandic Glossary". Árnastofnun (in Icelandic). Árnastofnun / The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Knörr, Henrike (2007). "Basque Fishermen in Iceland Bilingual vocabularies in the 17th and 18th centuries". Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ "Basknesk-íslensk orðasöfn / Basque-Icelandic glossaries". Árnastofnun (in Icelandic). Árnastofnun / The Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ a b Miglio 2008.

- ^ a b c Etxepare & Miglio.

- ^ Miglio 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Belluzzo, Nicholas (2007). "Viola Miglio and Ricardo Etxepare - 'A new Basque - Icelandic glossary of the 17th century.'". Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ Deen 1937, pp. 102–105.

- ^ From the Basque Wikipedia and the French Wikipedia.

- ^ a b Deen 1937, p. 103.

- ^ Miglio 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Deen 1937, p. 102.

- ^ Mitxelena, Koldo (2005). Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia. Euskaltzaindia. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ a b Hualde 2014.

- ^ Deen 1937, p. 104.

- ^ Pidgins and Creoles : an introduction. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins. 1995. p. 32. ISBN 9789027252364.

- ^ Deen 1937, p. 101.

- ^ Miglio 2006, p. 200.[full citation needed]

- ^ Etxepare & Miglio, p. 282.

- ^ Etxepare & Miglio, p. 286.

- ^ Etxepare & Miglio, p. 305.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bakker, Peter (1987). "A Basque Nautical Pidgin: A Missing Link in the History of FU". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 2 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1075/jpcl.2.1.02bak. ISSN 0920-9034.

- Bakker, Peter; Bilbao, Gidor; Deen, Nicolaas Gerard Hendrik; Hualde, Jose Ignacio (1991). "Basque Pidgins in Iceland and Canada". Anejos del Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca "Julio de Urquijo" (in Basque). 23. Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018.

- Deen, Nicolaas Gerard Hendrik (1937). Glossaria duo vasco-islandica (Doctoral thesis) (in Latin). Re-printed in 1991 in Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca Julio de Urquijo Vol. 25, Nº. 2, pp. 321–426 (in Basque). Archived on 2019-03-01.

- Etxepare, Ricardo; Miglio, Viola Giula, A Fourth Basque-Icelandic Glossary (PDF)

- Guðmundsson, Helgi (1979). Um þrjú basknesk-íslenzk orðasöfn frá 17. öld (in Icelandic). Reykjavík: Íslenskt mál og almenn málfræði. pp. 75–87.

- Holm, John A. (1988–1989). Pidgins and creoles. Cambridge Languages Surveys. Cambridge University Press. pp. 628–630. ISBN 978-0521249805. OCLC 16468410.

- Hualde, José Ignacio (1984). "Icelandic Basque pidgin" (PDF). Journal of Basque Studies in America. 5: 41–59.

- Hualde, José Ignacio (2014). "Basque Words". Lapurdum (18): 7–21. doi:10.4000/lapurdum.2472. ISSN 1273-3830.

- Miglio, Viola Giula (2008). ""Go shag a horse!": The 17th-18th century Basque-Icelandic glossaries revisited" (PDF). Journal of the North Atlantic. I: 25–36. doi:10.3721/071010. S2CID 162196883. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2017.

- Yraola, Aitor (1983). "Um baskneska fiskimenn á Norður-Atlantshafi". Saga (in Icelandic). 21. Translated by Sigrún Á. Eíríksdóttir: 27–38. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2019.

Manuscripts

[edit]- Vocabula Gallica (French words) – Written in the latter part of the 17th century, a total of 16 pages. A part of Jón Ólafsson's manuscript "AM 987 4to".

- Vocabula Biscaica (Basque words) – A copy written in the 18th century by Jón Ólafsson, a total of 10 pages. A part of his manuscript "AM 987 4to".

- The Harvard Manuscript – Two pages, a part of the manuscript "MS Icelandic 3" which contains 145 sheets.

Further reading

[edit]- Miglio, Viola Giula (2008). ""Go shag a horse!": The 17th-18th century Basque-Icelandic glossaries revisited" (PDF). Journal of the North Atlantic. I: 25–36. doi:10.3721/071010. S2CID 162196883. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2017.

- Etxepare, Ricardo; Miglio, Viola Giula, A Fourth Basque-Icelandic Glossary (PDF)