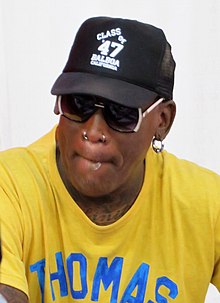

Dennis Rodman

Dennis Keith Rodman (born May 13, 1961) is an American former professional basketball player. Renowned for his defensive and rebounding abilities, his biography on the official NBA website states that he is "arguably the best rebounding forward in NBA history". Nicknamed "the Worm",[2] he played for the Detroit Pistons, San Antonio Spurs, Chicago Bulls, Los Angeles Lakers, and Dallas Mavericks of the National Basketball Association (NBA). Rodman played at the small forward position in his early years before becoming a power forward.

He earned NBA All-Defensive First Team honors seven times and won the NBA Defensive Player of the Year Award twice. He also led the NBA in rebounds per game for a record seven consecutive years and won five NBA championships. On April 1, 2011, the Pistons retired Rodman's No. 10 jersey,[3] and he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame later that year.[4] In October 2021, Rodman was honored as one of the league's greatest players of all-time by being named to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team.[5]

Rodman experienced an unhappy childhood and was often described as shy and introverted in his early years. After aborting a suicide attempt in 1993, he reinvented himself as a "bad boy" and became notorious for numerous controversial antics. He repeatedly dyed his hair in artificial colors, had many piercings and tattoos, and regularly disrupted games by clashing with opposing players and officials. He famously wore a wedding dress to promote his 1996 autobiography Bad as I Wanna Be. Rodman also attracted international attention for his visits to North Korea and his subsequent befriending of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in 2013.

In addition to being a former professional basketball player, Rodman has appeared in professional wrestling. He was a member of the nWo and fought alongside Hulk Hogan in the main event of two Bash at the Beach pay-per-views. In professional wrestling, Rodman was the first-ever winner of the Celebrity Championship Wrestling tournament. He had his own TV show, The Rodman World Tour, and had starring roles in the action films Double Team (1997) and Simon Sez (1999). He appeared in several reality TV series and was the winner of the $222,000 main prize of the 2004 edition of Celebrity Mole.

Early life

Rodman was born in Trenton, New Jersey, the son of Shirley and Philander Rodman, Jr., an Air Force enlisted member, who later fought in the Vietnam War. When he was young, his father left his family, eventually settling in the Philippines.[6] Rodman has many brothers and sisters: according to his father, he has either 26 or 28 siblings on his father's side. However, Rodman has stated that he is the oldest of a total of 47 children.[6][7][8]

After his father left, Shirley took many odd jobs to support the family, up to four at the same time.[9] In his 1996 biography Bad As I Wanna Be, he expresses his feelings for his father: "I haven't seen my father in more than 30 years, so what's there to miss ... I just look at it like this: Some man brought me into this world. That doesn't mean I have a father".[6] He would not meet his father again until 2012.[10]

Rodman and his two sisters, Debra and Kim,[11] grew up in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas,[12] at the time one of the most impoverished areas of the city.[13] Rodman's mother gave him the nickname "The Worm" for how he wiggles while playing pinball.[14] Rodman was so attached to his mother that he refused to move when she sent him to a nursery when he was four years old. According to Rodman, his mother was more interested in his two sisters, who were both considered more talented than he was in basketball and made him a laughingstock whenever he tagged along with them. He felt generally "overwhelmed" by the all-female household.[15] Debra and Kim would go on to become All-Americans at Louisiana Tech and Stephen F. Austin, respectively. Debra won two national titles with the Lady Techsters.[11]

While attending South Oak Cliff High School, Rodman was a gym class student of future Texas A&M basketball coach Gary Blair.[16] Blair coached Rodman's sisters Debra and Kim, winning three state championships.[17] However, Rodman was not considered an athletic standout. According to Rodman, he was "unable to hit a layup" and was listed in the high school basketball teams but was either benched or cut from the squads. Measuring only 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) as a freshman in high school,[9] he also failed to make the football teams and was "totally devastated".[15]

College career

After finishing high school, Rodman worked as an overnight janitor at Dallas Fort Worth International Airport. He then experienced a sudden growth spurt from 5 ft 11 in (1.80 m) to 6 ft 7 in (2.01 m) and decided to try basketball again,[18] despite becoming even more withdrawn because he felt odd in his own body.[15]

A family friend tipped off the head coach of Cooke County College (now North Central Texas College) in Gainesville, Texas. In his single semester there, he averaged 17.6 points and 13.3 rebounds, before flunking out due to poor academic performance.[9] After his short stint in Gainesville, he transferred to Southeastern Oklahoma State University, an NAIA school. There, Rodman was a three-time NAIA All-American and led the NAIA in rebounding twice (1985, 1986). In three seasons there (1983–1986), he averaged 25.7 points and 15.7 rebounds,[19] and registered a .637 field goal percentage.[18] In 1986 he led his team to the NAIA semifinals where he scored 46 points in a single game, while grabbing a tournament-tying record 32 rebounds, as they finished the season with the highest ranking in school history, at No. 3 in the nation. This helped get him invited to the Portsmouth Invitational Tournament, a pre-draft camp for NBA hopefuls, where he won Most Valuable Player honors and caught the attention of the Detroit Pistons.[9]

During college, Rodman worked at a summer youth basketball camp, where he befriended camper Byrne Rich who was 13 years old at the time, who was shy and withdrawn due to a hunting accident in which he mistakenly shot and killed his best friend. The two became almost inseparable. Rich invited Rodman to his rural Oklahoma home; at first, Rodman was not well-received by the Riches due to the fact he was 22 years old and black, but the Riches were so grateful to him for bringing their son out of his shell that they were able to set aside their prejudices.[20] Although Rodman had severe family and personal issues himself, he "adopted" the Riches as his own in 1982 and went from the city life to "driving a tractor and messing with cows".[20] Though Rodman credited the Riches as his "surrogate family" that helped him through college, as of 2013 he had stopped communicating with the Rich family after Byrne's mother allegedly referred to Rodman as a "nigger".[21]

Professional basketball career

Detroit Pistons (1986–1993)

Early years and first championship (1986–1989)

Rodman made himself eligible for the 1986 NBA draft. He was drafted by the Detroit Pistons as the third pick in the second round (27th overall), joining the rugged team of coach Chuck Daly that was called "Bad Boys" for their hard-nosed approach to basketball. The squad featured Isiah Thomas and Joe Dumars at the guard positions, Adrian Dantley and Sidney Green at forward, and center Bill Laimbeer. Bench players who played more than 15 minutes per game were sixth man Vinnie Johnson and the backup forwards Rick Mahorn and John Salley.[22] Rodman fit well into this ensemble, providing 6.5 points, 4.7 rebounds and some tough defense in 15.0 minutes of playing time per game.[19]

Winning 52 games, the Pistons comfortably entered the 1987 playoffs. They swept the Washington Bullets and soundly beat the Atlanta Hawks in five games but bowed out in seven matches against the archrival Boston Celtics in what was called one of the physically and mentally toughest series ever. Rodman feuded with Celtics guard Dennis Johnson and taunted Johnson in the closing seconds when he waved his right hand over his own head. As the Celtics closed out Game Seven, Johnson went back to Rodman in the last moments of the game and mimicked his taunting gesture.[23]

After the loss, Rodman made headlines by saying Celtics star Larry Bird was overrated because he was white. "Larry Bird is overrated in a lot of areas....Why does he get so much publicity? Because he's white. You never hear about a black player being the greatest". Although teammate Thomas supported him, he endured harsh criticism, but avoided being called a racist because, according to him, his own girlfriend Anicka "Annie" Bakes was white.[9][15]

In the following 1987–88 season, Rodman steadily improved his stats, averaging 11.6 points and 8.7 rebounds and starting in 32 of 82 regular season games.[19] The Pistons fought their way into the 1988 NBA Finals, and took a 3–2 lead, but lost in seven games against the Los Angeles Lakers. In Game Six, the Pistons were down by one point with eight seconds to go; Dumars missed a shot, and Rodman just fell short of an offensive rebound and a putback that could have won the title. In Game Seven, L.A. led by 15 points in the fourth quarter, but Rodman's defense helped cut down the lead to six with 3:52 minutes to go and to two with one minute to go. But then, he fouled Magic Johnson, who hit a free throw, missed an ill-advised shot with 39 seconds to go, and the Pistons never recovered.[24] In that year, he and his girlfriend Annie had a daughter they named Alexis.[9]

Rodman remained a bench player during the 1988–89 season, averaging 9.0 points and 9.4 rebounds in 27 minutes, yet providing such effective defense that he was voted into the All-Defensive Team, the first of eight times in his career.[19] He also began seeing more playing time after Adrian Dantley was traded at midseason to Dallas for Mark Aguirre. In that season, the Pistons finally vanquished their playoffs bane by sweeping the Boston Celtics, then winning in six games versus the Chicago Bulls—including scoring champion Michael Jordan—and easily defeating the Lakers 4–0 in the 1989 NBA Finals. Rodman was hampered by back spasms but dominated the boards, grabbing 19 rebounds in Game 3 and providing tough interior defense.[25]

Second championship and rebounding titles (1989–1993)

In the 1989–90 season, Detroit lost perennial defensive forward Rick Mahorn, who was taken by the Minnesota Timberwolves in that year's expansion draft and ended up on the Philadelphia 76ers when the Pistons could not reacquire him. It was feared that the loss of Mahorn – average in talent, but high on hustle and widely considered a vital cog of the "Bad Boys" teams – would diminish the Pistons' spirit, but Rodman seamlessly took over his role.[26] Averaging 8.8 points and 9.7 rebounds while starting in the last 43 regular-season games, he established himself as the best defensive player in the game, lauded by the NBA "for his defense and rebounding skills, which were unparalleled in the league".[18] Rodman's feats drew him his first big individual accolade: the NBA Defensive Player of the Year Award. He also had a .595 field goal percentage, best in the league.[19] In the 1990 playoffs, the Pistons beat the Bulls again, and in the 1990 NBA Finals, Detroit met the Portland Trail Blazers. Rodman suffered from an injured ankle and was often replaced by Mark Aguirre, but even without his defensive hustle, Detroit beat Portland in five games and claimed their second title.[26]

During the 1990–91 season, Rodman finally established himself as the starting small forward of the Pistons. He played such strong defense that the NBA said he "could shut down any opposing player, from point guard to center".[18] After coming off the bench for most of his earlier years, he started in 77 of the 82 regular-season games, averaged 8.2 points and 12.5 rebounds, and won his second Defensive Player of the Year Award.[19] In the 1991 playoffs, the Pistons were swept by the Chicago Bulls in the Eastern Conference Finals. The Bulls went on to win the championship.

In the 1991–92 season, Rodman made a remarkable leap in his rebounding. He collected an astounding 18.7 per game, winning his first of seven consecutive rebounding crowns, along with scoring 9.8 points per game, and making his first All-NBA Team.[19] His 1,530 season rebounds (the most since Wilt Chamberlain's 1,572 in the 1971–1972 season) have not since been surpassed. (Kevin Willis, who grabbed 1,258 boards that same season, came closest.[27] Willis lamented that Rodman had an advantage in winning the rebounding title with his lack of offensive responsibilities.[28]) In a March 1992 game, Rodman grabbed a career-high 34 rebounds.[29] However, the aging Pistons were eliminated by the up-and-coming New York Knicks in the first round of the 1992 playoffs.

Rodman experienced a tough loss when coach Chuck Daly, whom he had admired as a surrogate father, resigned in May; Rodman skipped the preseason camp and was fined $68,000.[9] The following 1992–93 season was even more tumultuous. Rodman and Annie Bakes, the mother of his daughter Alexis, were divorcing[30] after a short marriage, an experience which left him traumatized.[31] The Pistons won only 40 games and missed the 1993 playoffs entirely.

Four years later in his biography Bad As I Wanna Be, Rodman revealed just how far he had fallen. He had driven to The Palace of Auburn Hills in February 1993 late one night carrying a loaded rifle in his truck, debating whether or not he wanted to continue living. Eventually he fell asleep in the truck, where he was found by police who had been called to perform a welfare check on Rodman by a friend. It was in that moment that he had an epiphany: "I decided that instead [of killing myself] I was gonna kill the impostor that was leading Dennis Rodman to a place he didn't want to go ... So I just said, 'I'm going to live my life the way I want to live it and be happy doing it.' At that moment I tamed [sic] my whole life around. I killed the person I didn't want to be."[13] The book was later adapted for a TV movie Bad As I Wanna Be: The Dennis Rodman Story. Although he had three years and $11.8 million remaining on his contract, Rodman demanded a trade. On October 1, 1993, the Pistons dealt him to the San Antonio Spurs.[9]

San Antonio Spurs (1993–1995)

Playoff upset (1993–1994)

In the 1993–94 season, Rodman joined a Spurs team that was built around perennial All-Star center David Robinson, with a supporting cast of forwards Dale Ellis, Willie Anderson and guard Vinny Del Negro.[32] On the hardwood, Rodman now was played as a power forward and won his third straight rebounding title, averaging 17.3 boards per game, along with another All-Defensive Team call-up.[19] Living up to his promise of killing the "shy imposter" and "being himself" instead, Rodman began to show first signs of unconventional behavior: before the first game, he shaved his hair and dyed it blonde, which was followed up by stints with red, purple, blue hair and a look inspired from the film Demolition Man.[18] During the season, he headbutted Stacey King and John Stockton, refused to leave the hardwood once after being ejected, and had a highly publicized affair with Madonna.[9][33] The only player to whom Rodman related was reserve center Jack Haley, who earned his trust by not being shocked after a visit to a gay bar.[34] However, despite a 55-win season, Rodman and the Spurs did not survive the first round of the 1994 playoffs and bowed out against the Utah Jazz in four games.

Team conflict and shoulder injury (1994–1995)

In the following 1994–95 season, Rodman clashed with the Spurs front office. He was suspended for the first three games, took a leave of absence on November 11, and was suspended again on December 7. He finally returned on December 10 after missing 19 games.[18] After joining the team, he suffered a shoulder separation in a motorcycle accident, limiting his season to 49 games. Normally, he would not have qualified for any season records for missing so many games, but by grabbing 823 rebounds, he just surpassed the 800-rebound limit for listing players and won his fourth straight rebounding title by averaging 16.8 boards per game and made the All-NBA Team.[18] The Spurs won 62 games.

However, things fell apart in the playoffs. During the second round series against the Los Angeles Lakers, Rodman was suspended for insubordination for sitting on the floor with his shoes off during a timeout. Despite this, the Spurs advanced to the Western Conference Finals against their division rivals, the Houston Rockets. The Rockets had only recorded 47 wins and had to come back from a 3-1 deficit to win their previous series against the Phoenix Suns, but the team was the defending NBA champion, and it was thought that Rockets center Hakeem Olajuwon would have a hard time asserting himself versus Robinson and Rodman, who had both been voted into the NBA All-Defensive Teams.[18]

The Spurs, however, were never able to stop Olajuwon as he averaged 35.3 points per game in the series. Rodman was particularly critical of Spurs coach Bob Hill's play calling, saying that he coached the playoffs "like we were playing Minnesota in the middle of December" and that his idea that Rodman should assist Robinson, who he accused of freezing up in big moments, in defending Olajuwon was counterproductive because it would force him off his man and leave the Spurs prone to giving up scoring opportunities. He even went off on the organization, including general manager Gregg Popovich, in the locker room following a game, saying that everything they did "sucked" and that Hill was "a loser". The Spurs would lose in six games, in a series Rodman said they "could have and SHOULD have" won.

Rodman admitted his frequent transgressions, but asserted that he lived his own life and thus a more honest life than most other people:

I just took the chance to be my own man ... I just said: "If you don't like it, kiss my ass." ... Most people around the country, or around the world, are basically working people who want to be free, who want to be themselves. They look at me and see someone trying to do that ... I'm the guy who's showing people, hey, it's all right to be different. And I think they feel: "Let's go and see this guy entertain us."[13]

Chicago Bulls (1995–1998)

Third championship (1995–1996)

Before the 1995–96 season, Rodman was traded to the Chicago Bulls for center Will Perdue to fill a void at power forward left by Horace Grant, who had left the team before the 1994–95 season.[35][36] Rodman could not wear No. 10 jersey because the Bulls had retired it for Bob Love, and the NBA denied him the reversion 01, Rodman instead picked the number 91, whose digits add up to 10.[37] Although the trade for the already 34-year-old and volatile Rodman was considered a gamble at that time,[18] the power forward quickly adapted to his new environment, helped by the fact that his best friend Jack Haley was also traded to the Bulls.[38] Under coach Phil Jackson, he averaged 5.5 points and 14.9 rebounds per game, winning yet another rebounding title, and was part of the great Bulls team that won 72 of 82 regular season games, an NBA record at the time.[39] About playing next to the iconic Jordan and co-star Scottie Pippen, Rodman said:

On the court, me and Michael are pretty calm and we can handle conversation. But as far as our lives go, I think he is moving in one direction and I'm going in the other. I mean, he's goin' north, I'm goin' south. And then you've got Scottie Pippen right in the middle. He's sort of the equator.[13]

Although struggling with calf problems early in the season, Rodman grabbed 20 or more rebounds 11 times and had his first triple-double against the Philadelphia 76ers on January 16, 1996, scoring 10 points and adding 21 rebounds and 10 assists; by playing his trademark tough defense, he joined Jordan and Pippen in the All-NBA Defense First Team. On March 16, 1996, Rodman head butted referee Ted Bernhardt during a game in New Jersey; he was suspended for six games and fined $20,000, a punishment that was criticized as too lenient by the local press.[40]

In the 1996 playoffs, Rodman scored 7.5 points and grabbed 13.7 rebounds per game and had a large part in the six-game victory against the Seattle SuperSonics in the 1996 NBA Finals: in Game Two at home in the Bulls' United Center, he grabbed 20 rebounds, among them a record-tying 11 offensive boards, and in Game Six, again at the United Center, the power forward secured 19 rebounds and again 11 offensive boards, scored five points in a decisive 12–2 Bulls run, unnerved opposing power forward Shawn Kemp and caused Seattle coach George Karl to say: "As you evaluate the series, Dennis Rodman won two basketball games. We controlled Dennis Rodman for four games. But Game 2 and tonight, he was the reason they were successful."[41] His two games with 11 offensive rebounds each tied the NBA Finals record of Elvin Hayes.[18]

Rodman garnered much publicity for his public antics.[33] In 1996, Rodman wore a wedding dress to promote his autobiography Bad As I Wanna Be, claiming that he was bisexual and that he was marrying himself.[42]

Suspensions and fourth championship (1996–1997)

In the 1996–97 season, Rodman won his sixth rebounding title in a row with 16.7 boards per game, along with 5.7 points per game, but failed to rank another All-Defensive Team call-up.[19] However, he made more headlines for his notorious behavior. On January 15, 1997, he was involved in an incident during a game against the Minnesota Timberwolves. After tripping over cameraman Eugene Amos, Rodman kicked Amos in the groin. Though he was not assessed a technical foul at the time, he ultimately paid Amos a $200,000 settlement, and the league suspended Rodman for 11 games without pay. Thus, he effectively lost $1 million.[43] Missing another three games to suspensions, often getting technical fouls early in games[18] and missing an additional 13 matches due to knee problems, Rodman was not as effective in the 1997 playoffs, in which the Bulls reached the 1997 NBA Finals against the Utah Jazz. He struggled to slow down Jazz power forward Karl Malone but did his share to complete the six-game Bulls victory.[44]

Fifth ring and Finals controversy (1997–1998)

The regular season of the 1997–98 season ended with Rodman winning his seventh consecutive rebounding title with 15.0 boards per game, along with 4.7 points per game.[19] He grabbed 20 or more rebounds 11 times, among them a 29-board outburst against the Atlanta Hawks and 15 offensive boards (along with ten defensive) versus the Los Angeles Clippers.[18] Led by the aging Jordan and Rodman (respectively 35 and 37 years old), the Bulls reached the 1998 NBA Finals, again versus the Jazz. After playing strong defense on Malone in the first three games,[45] he caused major consternation when he left his team prior to Game Four to go wrestling with Hulk Hogan. He was fined $20,000, but it was not even ten percent of what he earned with this stint.[33] However, Rodman's on-court performance remained top-notch, again shutting down Malone in Game Four until the latter scored 39 points in a Jazz Game Five win, bringing the series to 3–2 from the Bulls perspective. In Game Six, Jordan hit the decisive basket after a memorable drive on Jazz forward Bryon Russell, the Bulls won their third title in a row and Rodman his fifth ring.[45]

After the 1997–98 season, the Bulls started a massive rebuilding phase, largely at the behest of general manager Jerry Krause. Head coach Phil Jackson and several members of the team left via free agency or retirement, including Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Steve Kerr, and Jud Buechler.[46] Rodman was released by the Bulls on January 21, 1999, before the start of the lockout-shortened 1998–99 season.[47]

Los Angeles Lakers (1999)

With his sister acting as his agent at the time, Rodman joined the Los Angeles Lakers, for a pro-rated salary for the remainder of the 1998–1999 season. With the Lakers he played in only 23 games, in which he started in 11 of them and averaged 2 points and 11 rebounds per game and was released in the offseason.[19]

Dallas Mavericks (2000)

In the 1999–2000 season, the then-38-year-old power forward Rodman was signed by the Dallas Mavericks, returning Rodman to his hometown. Dallas had won 10 of 13 before his arrival but went just 4–9 until he was waived by the Mavericks. He played 12 games, received six technical fouls, was ejected twice, and served a one-game suspension.[48][49] While averaging 14.3 rebounds per game, above his career average of 13.1, Rodman alienated the franchise with his erratic behavior and did not provide leadership to a team trying to qualify for their first playoffs in 10 years.[48] Dallas guard Steve Nash commented that Rodman "never wanted to be [a Maverick]" and therefore was unmotivated.[50]

Long Beach Jam (2003–2004)

After his NBA career, Rodman took a long break from basketball and concentrated on his film career and on wrestling.

After a longer hiatus, Rodman returned to play basketball for the Long Beach Jam of the newly formed American Basketball Association during the 2003–04 season, with hopes of being called up to the NBA midseason.[51] While he did not get that wish that season, he did help the Jam win the ABA championship in their inaugural season.

Fuerza Regia (2004)

Rodman also played in Mexico, with Fuerza Regia in 2004.[52]

Orange County Crush (2004–2005)

In the following 2004–05 season, Rodman signed with the ABA's Orange County Crush[53]

Tijuana Dragons (2005–2006)

Rodman played the following season with the ABA's Tijuana Dragons.[54] In November 2005, he played one match for Torpan Pojat of Finland's basketball league, Korisliiga.[33][55]

Brighton Bears (2006)

The return to the NBA never materialized, but on January 26, 2006, it was announced that Rodman had signed a one-game "experiment" deal for the UK basketball team Brighton Bears of the British Basketball League to play Guildford Heat on January 28[56] and went on to play three games for the Bears.[54] In spring 2006, he played two exhibition games in the Philippines along with NBA ex-stars Darryl Dawkins, Kevin Willis, Calvin Murphy, Otis Birdsong and Alex English. On April 27, they defeated a team of former Philippine Basketball Association stars in Mandaue City, Cebu and Rodman scored five points and grabbed 18 rebounds.[57] On May 1, 2006, Rodman's team played their second game and lost to the Philippine national basketball team 110–102 at the Araneta Coliseum, where he scored three points and recorded 16 rebounds.[58]

On April 4, 2011, it was announced that Rodman would be inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.[59]

NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Won an NBA championship | * | Led the league |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986–87 | Detroit | 77 | 1 | 15.0 | .545 | .000 | .587 | 4.3 | .7 | .5 | .6 | 6.5 |

| 1987–88 | Detroit | 82 | 32 | 26.2 | .561 | .294 | .535 | 8.7 | 1.3 | .9 | .5 | 11.6 |

| 1988–89† | Detroit | 82* | 8 | 26.9 | .595* | .231 | .626 | 9.4 | 1.2 | .7 | .9 | 9.0 |

| 1989–90† | Detroit | 82* | 43 | 29.0 | .581 | .111 | .654 | 9.7 | .9 | .6 | .7 | 8.8 |

| 1990–91 | Detroit | 82* | 77 | 33.5 | .493 | .200 | .631 | 12.5 | 1.0 | .8 | .7 | 8.2 |

| 1991–92 | Detroit | 82 | 80 | 40.3 | .539 | .317 | .600 | 18.7* | 2.3 | .8 | .9 | 9.8 |

| 1992–93 | Detroit | 62 | 55 | 38.9 | .427 | .205 | .534 | 18.3* | 1.6 | .8 | .7 | 7.5 |

| 1993–94 | San Antonio | 79 | 51 | 37.8 | .534 | .208 | .520 | 17.3* | 2.3 | .7 | .4 | 4.7 |

| 1994–95 | San Antonio | 49 | 26 | 32.0 | .571 | .000 | .676 | 16.8* | 2.0 | .6 | .5 | 7.1 |

| 1995–96† | Chicago | 64 | 57 | 32.6 | .480 | .111 | .528 | 14.9* | 2.5 | .6 | .4 | 5.5 |

| 1996–97† | Chicago | 55 | 54 | 35.4 | .448 | .263 | .568 | 16.1* | 3.1 | .6 | .3 | 5.7 |

| 1997–98† | Chicago | 80 | 66 | 35.7 | .431 | .174 | .550 | 15.0* | 2.9 | .6 | .2 | 4.7 |

| 1998–99 | L.A. Lakers | 23 | 11 | 28.6 | .348 | .000 | .436 | 11.2 | 1.3 | .4 | .5 | 2.1 |

| 1999–00 | Dallas | 12 | 12 | 32.4 | .387 | .000 | .714 | 14.3 | 1.2 | .2 | .1 | 2.8 |

| Career | 911 | 573 | 31.7 | .521 | .231 | .584 | 13.1 | 1.8 | .7 | .6 | 7.3 | |

| All-Star | 2 | 0 | 18.0 | .364 | — | — | 8.5 | .5 | .5 | .5 | 4.0 | |

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Detroit | 15 | 0 | 16.3 | .541 | — | .563 | 4.7 | .2 | .4 | 1.1 | 6.5 |

| 1988 | Detroit | 23 | 0 | 20.6 | .522 | .000 | .407 | 5.9 | .9 | .6 | .6 | 7.1 |

| 1989† | Detroit | 17 | 0 | 24.1 | .529 | .000 | .686 | 10.0 | .9 | .4 | .7 | 5.8 |

| 1990† | Detroit | 19 | 17 | 29.5 | .568 | — | .514 | 8.5 | .9 | .5 | .7 | 6.6 |

| 1991 | Detroit | 15 | 14 | 33.0 | .451 | .222 | .417 | 11.8 | .9 | .7 | .7 | 6.3 |

| 1992 | Detroit | 5 | 5 | 31.2 | .593 | .000 | .500 | 10.2 | 1.8 | .8 | .4 | 7.2 |

| 1994 | San Antonio | 3 | 3 | 38.0 | .500 | .000 | .167 | 16.0 | .7 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 8.3 |

| 1995 | San Antonio | 14 | 12 | 32.8 | .542 | .000 | .571 | 14.8 | 1.3 | .9 | .0 | 8.9 |

| 1996† | Chicago | 18 | 15 | 34.4 | .485 | — | .593 | 13.7 | 2.1 | .8 | .4 | 7.5 |

| 1997† | Chicago | 19 | 14 | 28.2 | .370 | .250 | .577 | 8.4 | 1.4 | .5 | .2 | 4.2 |

| 1998† | Chicago | 21 | 9 | 34.4 | .371 | .250 | .605 | 11.8 | 2.0 | .7 | .6 | 4.9 |

| Career | 169 | 89 | 28.3 | .490 | .149 | .540 | 9.9 | 1.2 | .6 | .6 | 6.4 | |

Legacy in basketball

From the beginning of his career, Rodman was known for his defensive hustle, which was later accompanied by his rebounding prowess. In Detroit, he was mainly played as a small forward, and his usual assignment was to neutralize the opponent's best player; Rodman was so versatile that he could guard centers, forwards, or guards equally well[18] and won two NBA Defensive Player of the Year Awards. From 1991 on, he established himself as one of the best rebounders of all time, averaging at least 15 rebounds per game in six of the next seven years.[19] Playing power forward as member of the Spurs and the Bulls, he had a historical outburst in the 1996 NBA Finals: he twice snared 11 offensive rebounds, equalling an all-time NBA record. In addition, he had a career-high 34-rebound game on March 4, 1992.[60] Rodman's rebounding prowess with Detroit and San Antonio was also aided by his decreased attention to defensive positioning and helping teammates on defense.[61][62][63] Daly said Rodman was selfish about rebounding, but deemed him a hard worker and coachable.[62] Rodman's defensive intensity returned while with Chicago.[63]

On offense, Rodman's output was mediocre. He averaged 11.6 points per game in his second season, but his average steadily dropped: in the three championship seasons with the Bulls, he averaged five points per game and connected on less than half of his field goal attempts.[19] His free throw shooting (lifetime average: .584) was considered a big liability: on December 29, 1997, Bubba Wells of the Dallas Mavericks committed six intentional fouls against him in only three minutes, setting the record for the fastest foul out in NBA history. The intention was to force him to attempt free throws, which in theory would mean frequent misses and easy ball possession without giving up too many points. However, this plan backfired, as Rodman hit 9 of the 12 attempts.[64] This was Dallas coach Don Nelson's early version of what would later develop into the famous "Hack-a-Shaq" method that would be implemented against Shaquille O'Neal, Dwight Howard, and other poor free throw shooters.

In 14 NBA seasons, Rodman played in 911 games, scored 6,683 points, and grabbed 11,954 rebounds, translating to 7.3 points and 13.1 rebounds per game in only 31.7 minutes played per game.[19][27] NBA.com lauds Rodman as "arguably the best rebounding forward in NBA history and one of the most recognized athletes in the world" but adds "enigmatic and individualistic, Rodman has caught the public eye for his ever-changing hair color, tattoos and, unorthodox lifestyle".[18] On the hardwood, he was recognized as one of the most successful defensive players ever, winning the NBA championship five times in six NBA Finals appearances (1989, 1990, 1996–1998; only loss 1988), being crowned NBA Defensive Player of the Year twice (1990–1991) and making seven NBA All-Defensive First Teams (1989–1993, 1995–1996) and NBA All-Defensive Second Teams (1994). He additionally made two All-NBA Third Teams (1992, 1995), two NBA All-Star Teams (1990, 1992) and won seven straight rebounding crowns (1992–1998) and finally led the league once in field goal percentage (1989).[19]

Rodman was recognized as the prototype bizarre player, stunning basketball fans with his artificial hair colors, numerous tattoos and body piercings, multiple verbal and physical assaults on officials, frequent ejections, and his tumultuous private life.[18] He was ranked No. 48 on the 2009 revision of SLAM Magazine's Top 50 Players of All-Time.[65] In 2021, to commemorate the NBA's 75th Anniversary The Athletic ranked their top 75 players of all time, and named Rodman as the 62nd greatest player in NBA history.[66] Metta World Peace played one year with the 91 jersey number in homage to Rodman, who he described as a player who he liked "on the court as a hustler, not when he kicked the cameraman."[67]

Professional wrestling career

| Dennis Rodman | |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Dennis Keith Rodman |

| Born | May 13, 1961 Trenton, New Jersey |

| Spouse(s) | Annie Bakes (divorced) Michelle Moyer

(m. 2003; div. 2012) |

| Children | 3 |

| Family | Shirley Rodman (mother) Philander Rodman Jr. (father) |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Impostor Sting Dennis Rodman |

| Billed height | 6 ft 7 in (2.01 m) |

| Billed weight | 220 lb (100 kg) |

| Billed from | Chicago, Illinois Los Angeles, California |

| Debut | March 10, 1997[68] |

| Retired | 2000 (first retirement) 2008 (second retirement) |

World Championship Wrestling (1997–1999)

Rodman took up his hobby of professional wrestling seriously and appeared on the edition of March 10 of Monday Nitro with his friend Hollywood Hulk Hogan in World Championship Wrestling (WCW). At the March 1997 Uncensored event, he appeared as a member of the nWo. His first match was at the July 1997 Bash at the Beach event, where he teamed with Hogan in a loss to Lex Luger and The Giant.[54] At the August 1997 Road Wild event, Rodman appeared as the Impostor Sting hitting Luger with a baseball bat to help Hogan win the WCW World Heavyweight Championship.

After the 1997–98 season, where Rodman and the Chicago Bulls defeated Karl Malone and the Utah Jazz in the 1998 NBA Finals, Rodman and Malone squared off again, this time in a tag team match at the July 1998 Bash at the Beach event. He fought alongside Hulk Hogan, and Malone tagged along with Diamond Dallas Page. In a poorly received match, the two power forwards exchanged "rudimentary headlocks, slams and clotheslines" for 23 minutes. Rodman bested Malone again as he and Hogan picked up the win.[69]

Rodman returned to WCW in 1999 and feuded with Randy Savage. This culminated in a match at Road Wild which Rodman lost.[70]

i-Generation Superstars of Wrestling and retirement (2000)

On July 30, 2000, Rodman competed on the i-Generation Superstars of Wrestling pay-per-view event.[71] He fought against i-Generation champion Curt Hennig in an Australian Outback match; Hennig won the match by disqualification. Following the match, Rodman refrained from wrestling at the top level and retired.[33]

Hulk Hogan's Celebrity Championship Wrestling (2008)

Rodman came out of retirement to appear as a contestant on Hulk Hogan's Celebrity Championship Wrestling, broadcast on CMT. Rodman was the winner of the series, defeating other challengers such as Butterbean and Dustin Diamond.

All Elite Wrestling (2023)

Rodman made an appearance on the September 2 episode of AEW Collision, where he was confronted by Jeff Jarrett, Jay Lethal, Sonjay Dutt and Satnam Singh.[72] During the segment he aligned himself with The Acclaimed and Billy Gunn and accompanied them to the ring the following night during All Out on September 3, 2023.[73]

Championships and accomplishments

- Hulk Hogan's Celebrity Championship Wrestling

- Celebrity Championship Wrestling Tournament Champion

Media appearances

In 1995, Rodman appeared as himself in an episode of the CBS situation comedy Double Rush.[74][75]

In 1996, Rodman had his own MTV reality talk show called The Rodman World Tour, which featured him in a series of odd-ball situations.[76] That same year, Rodman had two appearances in releases by rock band Pearl Jam. A Polaroid picture of Rodman's eyeball is on the cover of the album No Code, and "Black, Red, Yellow", B-side of its lead single "Hail, Hail", was written about Rodman and has him contribute a voice message.[77]

A year later, he made his feature film debut in the action film Double Team alongside Jean-Claude Van Damme and Mickey Rourke. The film was critically panned and his performance earned him three Golden Raspberry Awards: Worst New Star, Worst Supporting Actor and Worst Screen Couple (shared with Van Damme).[78] Rodman starred in Simon Sez, a 1999 action/comedy and co-starred with Tom Berenger in a 2000 action film about skydiving titled Cutaway.[79] In 1998, he joined the cast of the syndicated TV show Special Ops Force, playing 'Deke' Reynolds, a flamboyant but skilled ex-Army helo pilot and demolitions expert.

In 2005, Rodman became the first man to pose naked for PETA's advertisement campaign "Rather Go Naked Than Wear Fur".[80] That same year, Rodman traveled to Finland, at first, he was present at Sonkajärvi in July in a wife-carrying contest. However, he resigned from the contest due to health problems.[81] Also in 2005, Rodman published his second autobiography, I Should Be Dead By Now; he promoted the book by sitting in a coffin.[33][3]

Rodman became Commissioner of the Lingerie Football League in 2005.[33][3]

Since his initial entry into acting, he has appeared in few acting roles outside of playing himself. Rodman has made an appearance in an episode of 3rd Rock from the Sun playing the character of himself, except being a fellow alien with the Solomon family.[79] He voiced an animated version of himself in the Simpsons episode "Treehouse of Horror XVI".

Rodman has also appeared in several reality shows: in January 2006, Rodman appeared on the fourth version of Celebrity Big Brother in the UK, and on July 26, 2006, in the UK series Love Island as a houseguest contracted to stay for a week.[79] Finally, he appeared on the show Celebrity Mole on ABC. He wound up winning the $222,000 grand prize.[82]

In 2008, Rodman joined as a spokesman for a sports website OPENSports.com, the brainchild of Mike Levy, founder and former CEO of CBS Sportsline.com. Rodman also writes a blog and occasionally answers members' questions for OPEN Sports.[83]

In 2009, he appeared as a contestant on Celebrity Apprentice. Throughout the season, each celebrity raised money for a charity of their choice; Rodman selected the Court Appointed Special Advocates of New Orleans. He was the fifth contestant eliminated, on March 29, 2009.

In 2013, he appeared again as a contestant on Celebrity Apprentice. He raised $20,000 for the Make-A-Wish Foundation and was the sixth contestant eliminated, on April 7, 2013.

In March 2013, Rodman arrived at the Vatican City during voting in the papal conclave for the selection of a new pope.[84][3] The trip was organized by an Irish gambling company.

In July 2013, Rodman joined Premier Brands to launch and promote Bad Boy Vodka.[85]

Rodman's visits to North Korea were depicted in the 2015 documentary film Dennis Rodman's Big Bang in Pyongyang.[86]

In 2017, Rodman was featured on the alternative R&B/hip-hop duo Mansionz's self-titled album Mansionz. He provides vocals on the single "Dennis Rodman" and uncredited vocals on "I'm Thinking About Horses". In 2020, Rodman again featured on a track named after him, on rapper ASAP Ferg's Floor Sears II mixtape.[87]

Personal life

Rodman had a highly publicized affair with Madonna in 1994.[88] Madonna arranged to meet Rodman by interviewing him for Vibe magazine.[89] They were intended to appear on the cover of the June/July 1994 issue, but it was shelved by the founder Quincy Jones.[90][91][92] Rodman claimed that they attempted to conceive a child because Madonna had offered him $20 million to impregnate her.[93]

Family

Rodman married his first wife Annie Bakes in September 1992.[9] They began dating in 1987, and had a daughter.[94][95] Their relationship was marred by infidelities and accusations of abuse.[94][96] They divorced after 82 days.[97][30]

On November 14, 1998, Rodman married model Carmen Electra at the Little Chapel of the Flowers in Las Vegas, Nevada.[98][99] Nine days later, Rodman filed for an annulment claiming he was of "unsound mind" when they married.[100] They reconciled, but Electra filed for divorce in April 1999.[100][98] She later stated that it was an "occupational hazard" to be "Rodman's girlfriend".[101]

In 1999, Rodman met Michelle Moyer, with whom he had a son, Dennis Jr. ("DJ", b. April 25, 2001)[102][103] and a daughter, Trinity (b. May 20, 2002). Moyer and Rodman married in 2003 on his 42nd birthday.[104] Michelle Rodman filed for divorce in 2004, although the couple spent several years attempting to reconcile. The marriage was officially dissolved in 2012, when Michelle again petitioned the court to grant a divorce. It was reported that Rodman owed $860,376 in child and spousal support.[105]

DJ started playing college basketball for Washington State in 2019. He later transferred to USC in 2023. His daughter Trinity is a professional soccer player for the Washington Spirit,[106] and the United States national team. In a 2024 interview, Trinity rarely heard from him growing up and as an adult, saying, "He’s not a dad. Maybe by blood, but nothing else."[107]

On July 14, 2020, Rodman's father Philander died of prostate cancer in Angeles City, Philippines, at age 79. Dennis had previously reconciled with his father in 2012 when he made a trip to the Philippines after years of being estranged.[108]

Alcohol issues

Rodman entered an outpatient rehab center in Florida in May 2008.[109] In May 2009, his behavior on Celebrity Apprentice led to an intervention which included Phil Jackson as well as Rodman's family and other friends. Rodman initially refused to enter rehabilitation because he wanted to attend the Celebrity Apprentice reunion show.[110][111] In 2009, Rodman agreed to appear on the third season of Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew.[112][113] Rodman remained a patient at the Pasadena Recovery Center for the 21-day treatment cycle. A week after completion he entered a sober-living facility in the Hollywood Hills, which was filmed for the second season of Sober House. During episode seven of Sober House, Rodman was shown being reunited with his mother Shirley, from whom he had been estranged for seven years.[114] During this same visit Shirley also met Rodman's two children for the first time.[115] On January 10, 2010, on the same day that Celebrity Rehab premiered, Rodman was removed from an Orange County (California) restaurant for disruptive behavior.[116] In March 2012, Rodman's financial advisor said, "In all honesty, Dennis, although a very sweet person, is an alcoholic. His sickness impacts his ability to get work."[117]

On January 15, 2014, Rodman again entered a rehabilitation facility to seek treatment for alcohol abuse. This came on the heels of a well-publicized trip to North Korea where his agent, Darren Prince, reported he had been drinking heavily and to an extent "that none of us had seen before."[118]

Legal troubles

Rodman has settled several lawsuits out of court for alleged sexual assault.[97][119]

In August 1999, Rodman was arrested for public drunkenness and spent the night in jail after he got into an altercation at Woody's Wharf in Newport Beach, California. The charges were eventually dropped.[120]

On November 5, 1999, Rodman and his then-wife, Carmen Electra, were charged with misdemeanor battery after police were notified of a domestic disturbance.[120][121] Each posted bail worth $2,500 and were released with a temporary restraining order placed on them. The charges were dropped the next month.[122]

In December 1999, Rodman was arrested for drunk driving and driving without a valid driver's license. In July 2000, Rodman pleaded guilty to both charges and was ordered to pay $2,000 in fines as well as attend a three-month treatment program.[123]

In 2002, he was arrested for interfering with police investigating a code violation at a restaurant he owned; the charges were eventually dropped.[9] After settling down in Newport Beach, California, the police appeared over 70 times at his home because of loud parties.[9] In early 2003, Rodman was arrested and charged with domestic violence at his home in Newport Beach for allegedly assaulting his then-fiancée.[124]

In April 2004, Rodman pleaded nolo contendere (no contest) to drunk driving in Las Vegas. He was fined $1,000 and ordered to serve 30 days of home detention.[125] On April 30, 2008, Rodman was arrested following a domestic violence incident at a Los Angeles hotel.[126] On June 24, 2008, he again pleaded no contest to the misdemeanor spousal battery charges. He received three years of probation and was ordered to undergo one year of domestic violence counseling as well as 45 hours of community service, which were to involve some physical labor activities.[127][128]

On November 21, 2016, Rodman was charged with causing a hit and run accident, lying to police, and driving without a license following an incident on Interstate 5 near Santa Ana, California, in July.[129] In February 2017, Rodman pleaded guilty to the charges. He was sentenced to three years of probation and 30 hours of community service. He was also ordered to pay restitution and donate $500 to the Victim Witness Emergency Fund.[130]

In January 2018, Rodman was arrested for driving under the influence in Newport Beach. He pleaded guilty to two misdemeanor charges and received three years of probation.[131]

In May 2019, the Los Angeles Times reported that Newport Beach yoga studio owner Ali Shah accused Rodman of helping steal over $3,500 worth of items from the studio's reception area, including a 400 lb (180 kg) decorative geode. Rodman disputed the account, claiming the owner told him "Dennis, get anything you want." No charges had been filed at the time of reporting.[132]

On October 18, 2019, Rodman was charged with misdemeanor battery after slapping a man at the Buddha Sky Bar in Delray Beach, Florida.[133]

Rodman was one of the victims of professional scam artist/fraudster Peggy Ann Fulford (Peggy King, Peggy Williams, Peggy Ann Barard, etc.), losing $1.24 million, amongst the $5.79 million in total she stole from him, Ricky Williams, Travis Best, Rashad McCants, Lex Hilliard and others.[134] Fulford's crimes included stealing funds Rodman believed were being distributed as child-support payments he owed to his first wife, contributing to an unsuspecting Rodman – in 2012 – being left trying to explain the missed payments in an Orange County, California, court; the issue was clarified when Fulford was indicted by the FBI in 2016.[134] She continued her criminal activity until sentenced, in February 2018, to 10 years in prison and full financial restitution (unlikely) to her victims.[134]

Politics

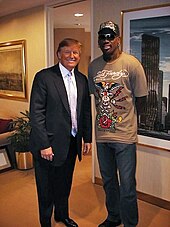

On July 24, 2015, Rodman publicly endorsed Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign. That same month, Rodman sent out an endorsement tweet, stating, "Donald Trump has been a great friend for many years. We don't need another politician, we need a businessman like Mr. Trump! Trump 2016."[135][136]

In 2020, Rodman endorsed and campaigned for the presidential campaign of rapper Kanye West.[137]

North Korea visits

On February 26, 2013, Rodman made a trip to North Korea with Vice Media correspondent Ryan Duffy to host basketball exhibitions.[3][138][139] He met North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.[140][141] Rodman and his travel party were the first Americans to meet Kim.[142] He later said that Kim was "a friend for life"[143] and suggested that President Barack Obama "pick up the phone and call" Kim, since the two leaders were basketball fans.[144] On May 7, after reading an article in The Seattle Times,[145] Rodman sent out a tweet asking Kim to release American prisoner Kenneth Bae, who had been sentenced to 15 years of hard labor in North Korea.[146][147][3] Kim released Bae the following year.

In July 2013, Rodman told Sports Illustrated: "My mission is to break the ice between hostile countries. Why it's been left to me to smooth things over, I don't know. Dennis Rodman, of all people. Keeping us safe is really not my job; it's the black guy's [Obama's] job. But I'll tell you this: If I don't finish in the top three for the next Nobel Peace Prize, something's seriously wrong."[3] On September 3, 2013, Rodman flew to Pyongyang for another meeting with Kim Jong Un.[148] He said that Kim has a daughter named Kim Ju-ae, and that he is a "great dad".[149] He also noted that he planned to train the North Korean national basketball team.[150] He stated that he is "trying to open Obama's and everyone's minds" and encouraged Obama to reach out to Kim Jong Un.[151]

In December 2013, Rodman announced that he would visit North Korea again. He also said that he has plans to take a number of former NBA players with him for an exhibition basketball tour.[152] According to Rory Scott, a spokesman for the exhibitions' sponsoring organization, Rodman planned to visit December 18–21 and train the North Korean team in preparation for January games. The games were scheduled for January 8 (Kim Jong Un's birthday) and January 10, 2014.[153] Included on the U.S. exhibition team were Kenny Anderson, Clifford Robinson, Vin Baker, Craig Hodges, Doug Christie, Sleepy Floyd, Charles D. Smith, and four streetballers.[154] Rodman departed from Beijing on January 6. Among his entourage was Irish media personality Matt Cooper, who had interviewed Rodman a number of times on the radio.[155][156]

Rodman made comments on January 7, 2014, during a CNN interview implying that Kenneth Bae was at fault for his imprisonment. The remarks were widely reported in other media outlets and provoked a storm of criticism. Two days later, Rodman apologized for his comments, saying that he had been drinking and under pressure. He added that he "should know better than to make political statements". Some members of Congress, the NBA, and human rights groups suggested that Rodman had become a public relations stunt for the North Korean government.[157] On May 2, 2016, Kenneth Bae credited Rodman with his early release. He said that Rodman's rant raised awareness of his case and that he wanted to thank him for his expedited release.[158]

On June 13, 2017, Rodman returned to North Korea on what was initially described as a sports-related visit to the country. "My purpose is to go over there and try to see if I can keep bringing sports to North Korea," he said.[159] He added that he hoped to accomplish "something that's pretty positive" during the visit. He met with national Olympic athletes and basketball players, viewed a men's basketball practice, and visited a state-run orphanage.[160][161] He was not able to meet with Kim Jong Un, but met instead with the nation's Minister of Sports and gave him several gifts for Kim, including two signed basketball jerseys, two soap sets, and a copy of Donald Trump's 1987 book The Art of the Deal.[162]

Rodman posted a video on Twitter that was recorded before he left for the visit in which he and his agent describe the mission of the trip. "He's going to try to bring peace between both nations," said Rodman's agent Chris Volo, referring to the strained relations between North Korea and the United States. Rodman added, "That's the main reason why we're going. We're trying to bring everything together. If not, at least we tried."[162] The visit was sponsored by the cryptocurrency company PotCoin.[163]

Rodman's "hoops diplomacy" inspired the 20th Century Fox comedy Diplomats. Tim Story and Peter Chernin are set to produce the film, while Jonathan Abrams is reportedly writing the script.[164][165][166][167]

Rodman visited North Korea again in June 2018. "I'm just happy to be a part of" the 2018 North Korea–United States summit, he said, "because I think I deserve it."[168]

There has been speculation that Rodman might be an intelligence officer working for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) on North Korea, with the CIA neither confirming nor denying existence of records concerning his employment.[169][170]

Presidential involvement suggested

The Washington Post raised the question of whether President Donald Trump sent Rodman on his 2017 visit to negotiate the release of several American prisoners of North Korea or to open a back channel for diplomatic communications.[171] The U.S. State Department, White House officials, and Rodman all denied any official government involvement in the visit. Rodman, who publicly endorsed Trump during the 2016 presidential campaign, is a self-described longtime friend of the president and, as the article put it, "Trump and Kim's only mutual acquaintance."[171] The Washington Post article stated, "Multiple people involved in unofficial talks with North Korea say that the Trump administration has been making overtures toward the Kim regime, including trying to set up a secret back channel to the North Korean leader using 'an associate of Trump's' rather than the usual lineup of North Korea experts and former officials who talk to Pyongyang's representatives."[171]

When asked if he had spoken with Trump about the visit, Rodman replied, "Well, I'm pretty sure he's pretty much happy with the fact that I'm over here trying to accomplish something that we both need."[172] Rodman publicly presented a copy of Trump's book, The Art of the Deal to North Korean officials, as a personal gift for Kim Jong Un. In a Twitter video posted by Rodman, his agent Chris Volo said, "He's the only person on the planet that has the uniqueness, the unbelievable privilege of being friends with President Trump and Marshal Kim Jong Un."[162] Rodman went on to say in the video that he wanted to bring peace and "open doors between both countries."

Otto Warmbier, an American student held captive in North Korea for 17 months, was released to U.S. officials the same day as Rodman's visit to North Korea. Despite the timeline of the two events, the U.S. State Department, The White House, and Rodman all flatly denied any diplomatic connection or coordination between Rodman's visit and the U.S. government. The U.S. State Department said the release of Warmbier was negotiated and secured by high level U.S. diplomats including Joseph Yun, the State Department's special envoy on North Korea.[173] Warmbier, who was in a nonresponsive coma throughout much of his imprisonment in North Korea, died days after being returned to his family in the U.S.[174]

In an emotional interview with Michael Strahan of Good Morning America, Rodman expressed sorrow for the death of Warmbier and said, "I was just so happy to see the kid released. Later that day, that's when we found out he was ill. No one knew that." He added that he wished to give "all the prayer and love" to the Warmbier family and had contacted them and hoped to meet with them personally.[175]

Rodman's agent, Chris Volo, told ABC News that before they left for the 2017 trip, he had asked North Korean officials to release Warmbier as a symbol of good faith for any future sports-relations visits. "I asked on behalf of Dennis for his release three times," Volo said.[175]

In December 2017, Columbia University professor of neurobiology Joseph Terwilliger, who has accompanied Rodman to North Korea, argued that "While I don't suspect that very many Americans would have chosen him to be an emissary or international goodwill ambassador, Dennis has had a long friendship with Mr. Trump and has also developed a very cordial friendship with Mr. Kim. In this tense climate, as we stand at a perilous crossing, Mr. Rodman's unique position as a friend to the leaders of both U.S. and North Korea could provide a much-needed bridge to help resolve the current nuclear standoff."[176]

Works

Books

- Rodman, Dennis (1994). Rebound: The Dennis Rodman Story. Crown. ISBN 0-517-59294-0.

- Rodman, Dennis (1996). Bad as I Wanna Be. Random House Publishing. ISBN 0-440-22266-4.

- Rodman, Dennis (1997). Walk on the Wild Side. Delacorte Press. ISBN 0-385-31897-9.

- Rodman, Dennis (2005). I Should Be Dead by Now. Sports Publishing LLC. ISBN 1-59670-016-5.

- Rodman, Dennis (2013). Dennis the Wild Bull. Neighborhood Publishers. ISBN 978-0-61575-249-5.

Films

- Eddie (1996) as Himself (cameo)

- Double Team (1997) as Yaz

- Simon Sez (1999) as Simon

- The Comebacks (2007) as Warden (cameo)

- Rodman: For Better or Worse (2019) as Himself

See also

- List of National Basketball Association career rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career playoff rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association annual rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association single-game rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association single-season rebounding leaders

Notes

- a Rodman's height has been listed at 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m), 6 ft 7 in (2.01 m), or 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m). NBA.com itself has been inconsistent.[177][178][179][180]

References

- ^ "NBA.com: Dennis Rodman Career Stats". NBA.com. March 3, 2011. Archived from the original on March 3, 2011.

- ^ Levy, Dan (June 10, 2013). "The Greatest Nicknames in NBA History". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lidz, Franz (July 8, 2013). "Dennis Rodman - As the Worm Turns". Vault. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Rodman, Mullin enshrined in Hall of Fame". Fox Sports. August 12, 2011. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ^ nba.com/75

- ^ a b c "Dennis Rodman's dad has 27 kids and runs a bar in the Philippines". Jet. September 23, 1996. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman Emotional Hall of Fame Speech". YouTube. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2012. at 5:30 mins.

- ^ "Just for the record, Rodman only has 28 siblings". NBC Sports. August 15, 2011. Archived from the original on September 17, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Puma, Mike (February 21, 2006). "Rodman, King or Queen of Rebounds?". ESPN. Archived from the original on July 23, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "NBA Hall of Famer Dennis Rodman finally meets his father after 42 years". CBS News. July 19, 2012. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^ a b "Big Hopes In Big Dance For Big 12 Champion and No. 4 Seeded Aggies". Texas A&M Athletic Department. March 15, 2007. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Rodman, Dennis (June 9, 1996). "After A Difficult Childhood In Projects Near Dallas, Dennis Rodman Reached A Turning Point As A Basketball Player At Southeastern Oklahoma. He Discovered A Surrogate Family That Taught Him Discipline, A Best Friend Who Taught Him Restraint, And A Game That Taught Him The Power Of Success". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Marvel, Mark (February 1997). "Ramrodman - interview with basketball player Dennis Rodman - Interview". BNET. Archived from the original on April 28, 2008. Retrieved September 1, 2008.

- ^ Poisuo, Pauli (May 4, 2020). "The Truth About Dennis Rodman's Famous Nickname". Grunge. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Bruce, Newman (May 2, 1988). "Black, White – and Gray: Piston Dennis Rodman's life was complicated by racial matters long before his inflammatory words about Larry Bird". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Big Hopes In Big Dance For Big 12 Champion and No. 4 Seeded Aggies". www.aggieathletics.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Jeff (March 30, 2011). "Gary Blair engineers women's hoops revival at Texas A&M". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Dennis Rodman bio". NBA. Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Dennis Rodman Statistics". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ a b Newman, Bruce (May 2, 1988). "Black, White–and Gray (Part 2)". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Rohan Nadkarni (September 10, 2019). "Dennis Rodman Needs A Hug". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "1986–87 Detroit Pistons". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Simmons, Bill (February 23, 2007). "Page 2 – DJ should have made Springfield while still alive". ESPN. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ "Lakers Capture the Elusive Repeat". NBA.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Waiting Game Ends for Impatient Pistons". NBA.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Bad Boys Still the Best". NBA.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "NBA & ABA Single Season Leaders and Records for Total Rebounds". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Barnard, Bill (March 22, 1992). "Rebounding rage". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2013.(subscription required)

- ^ "Indiana Pacers at Detroit Pistons Box Score, March 4, 1992". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Rumor: Rodman to Kings for Tisdale". Lodi News-Sentinel. June 11, 1993. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ "Rodman, King or Queen of Rebounds?". ESPN. February 21, 2006. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ^ "1993-94 San Antonio Spurs Roster and Stats". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hannigan, Dave (January 8, 2006). "The top 10 Dennis Rodman moments". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011.

- ^ Friend, Tom (April 20, 1995). "PRO BASKETBALL; A Nonconformist in a League of His Own". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 3, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Gano, Rick (October 3, 1995). "Bulls acquire Rodman from Spurs". Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Bulls Take a Chance on Rodman : Pro basketball: Controversial forward is traded from San Antonio for Will Perdue". Los Angeles Times. October 3, 1995. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Armour, Terry. Joining Bulls `Almost Like A Storybook' For Former Collins Prep Brown . October 6, 1995

- ^ Villanueva, Virgil (August 21, 2022). ""We spend a lot of time out there together" — Jack Haley on "babysitting" Dennis Rodman". Basketball Network - Your daily dose of basketball. Archived from the original on January 7, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ Hareas, John (March 28, 2007). "Best Ever? Ten Reasons Why". NBA.com. Archived from the original on November 21, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman and the $50,000 Mormon Fine". Archived from the original on January 11, 1998. Retrieved August 9, 2006.. Retrieved August 31, 2008

- ^ "Bulls' Record-Setting Season Ends in Victory". NBA.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Barboza, Craigh (May 12, 2020). "Remember when Dennis Rodman put on a wedding dress and claimed to marry himself?". CNN. Archived from the original on September 9, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Rodman to Pay Cameraman". The New York Times. January 21, 1997. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "MJ Adds More Finals Heroics to His Legacy". NBA.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Jordan's Jumper Secures Chicago's Sixth Title". NBA.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Krause cites health concerns for resignation". ESPN. April 7, 2003. Archived from the original on December 25, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "'The Last Dance': Timeline of Dennis Rodman's eventful, title-winning stint with Michael Jordan, Bulls". CBSSports.com. May 16, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Tomaso, Bruce (April 4, 2011). "Hall of Famer Dennis Rodman wasn't a fan of Cuban's style while with Mavericks". Dallas News. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Kroichick, Ron (March 11, 2000). "Showdown of the Clueless and Lowdown". SFGate.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

Well, six technical fouls and two ejections in 12 games seems like a fine place to start.

- ^ "Rodman critical of Mavericks' decision to release him". lubockonline.com. March 10, 2000. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Rodman to play season with Long Beach Jam". ESPN. December 22, 2003. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Rodman comes back, first in Mexico". www.chinadaily.com.cn. October 12, 2004. Archived from the original on April 7, 2005. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman signs with ABA team". USA Today. November 10, 2004. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Dennis Rodman Profile". www.interbasket.net. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Bechtel, Mark; Cannella, Stephen (November 14, 2005). "On The Road With ... Dennis Rodman". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman - Brighton Bears". www.burgesshilluncovered.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Manlosa, Rommel C. (April 29, 2006). "NBA Legends entertain". SunStar CEBU. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ Caluag, Randy (May 2, 2006). "RP five turns back Legends, 110-102". manilastandardtoday.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman, Chris Mullin into Hall". ESPN. April 5, 2011. Archived from the original on April 7, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ "NBA Single Game Leaders and Records for Total Rebounds". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- ^ Schmitz, Brian (March 31, 1996). "Hill and Spurs have hardly felt Rodman's loss". Orlando Sentinel. p. 5D. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ a b Halberstam, Dave (2012). Playing for Keeps: Michael Jordan and the World He Made. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781453286142. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

He'll cheat a little bit on his positioning on defense in order to get his rebounds.

- ^ a b Simmons, Bill (2009). The Book of Basketball: The NBA According to The Sports Guy. ESPN Books. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-345-51176-8.

- ^ Fischer, David (May 15, 2005). "Take My Record, Please". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- ^ "We Got 50!", Slam Magazine, August 2009

- ^ Buha, Jovan. "NBA 75: At No. 62, Dennis Rodman broke the mold of the conventional basketball star". The Athletic. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "NBA: 24–second clock". Deseret News. November 1, 2004. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman". Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Wong, Alex (June 1, 2018). "Remembering When the Rodman-Malone NBA Finals Feud in 1998 Led to a WCW Match". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ "Road Wild 1999 results". Wrestling Supercards and Tournaments. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ "25 Worst Wrestling Promotions Ever". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on November 19, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Wolstanholme, Danny (September 9, 2023). "Jeff Jarrett Opens Up About Seeing Dennis Rodman Return To Chicago At AEW All Out". Wrestling Inc. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ "AEW All Out 2023: The Acclaimed retain Trios World Titles with an assist from Dennis Rodman to end preshow | DAZN News US". DAZN. September 4, 2023. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ "tv.com Double Rush "I Left My Socks in San Antonio" Episode Summary Accessed June 5, 2021". Archived from the original on May 26, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ tv.com Double Rush "I Left My Socks in San Antonio" Episode Cast & Crew Accessed June 5, 2021[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mukherjee, Tiarra. Raging Bull . Entertainment Weekly, 1996, Retrieved August 31, 2008

- ^ Blistein, John. Watch Dennis Rodman Cradle Eddie Vedder During Chicago Show Archived November 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone, 2016, Retrieved August 31, 2018

- ^ "1997 Archives". Golden Raspberry Awards. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Dennis Rodman". IMDb. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Rodman To Strip For Peta". Contactmusic.com. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Caple, Jim. "The amazing race". ESPN. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Angie Everhart revealed as 'Celebrity Mole Yucatan' mole while Dennis Rodman wins $222,000". Reality TV World. February 19, 2004. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Basketball's Ultimate Bad-Boy Dennis Rodman Announces Partnership With OPEN Sports". Archived from the original on June 2, 2009. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ^ Owen, Paul (March 13, 2013). "Dennis Rodman at the Vatican: 'I want to be anywhere in the world I'm needed'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Settembre, Jeanette (July 12, 2013). "Former NBA star Dennis Rodman to launch his own Bad Boy Vodka brand". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ "Matt Cooper Broadcaster, Journalist, and biographer of Tony O'Reilly". Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "Floor Seats II by A$AP Ferg on Apple Music". Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2020 – via Apple Music.

- ^ "RODMAN, MADONNA LEAVE TRAIL OF HO-HUM SIGHTINGS". Deseret News. May 4, 1994. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Rodman, Dennis (1996). Bad as I wanna be. Internet Archive. New York : Delacorte Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-385-31639-2.

- ^ "THE MEDIA BUSINESS; Vibe Magazine Editor Resigns". The New York Times. May 3, 1994. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Quincy (2002). Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones. Broadway Books. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-7679-0510-7. Archived from the original on February 10, 2024. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (May 11, 1994). "KMD Rapped Over Cover Art". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Reese, Alexis (September 19, 2019). "Dennis Rodman Claims Madonna Offered Him $20 Million To Get Her Pregnant". VIBE.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "Piston's Rodman Hit With Paternity, Palimony Suits". Jet. July 3, 1989. p. 52. Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ Howard, Johnette (December 18, 1988). "Believe It: Dennis Rodman's Improbable Life Story". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ Bickley, Dan (August 18, 2015). No Bull: The Unauthorized Biography of Dennis Rodman. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-250-09505-3. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Rodrick, Stephen (June 1, 2003). "No Rebound". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "15 years ago, Carmen Electra and Dennis Rodman got married in Las Vegas". For The Win. November 21, 2013. Archived from the original on January 2, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Walls, Jeannette (August 2, 2006). "Rodman says Electra never got over him". TODAY.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Dennis Rodman And Carmen Electra Call It Quits After Six Months Of Marriage". Jet. April 26, 1999. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Fisher, Mike (April 28, 2020). "'The Last Dance,' Dallas Style: Rodman, Sex, Drugs & The Mavs". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "DJ Rodman". Washington State University. Archived from the original on May 7, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman Jr. transferring to JSerra, per now former coach". USA Today High School Sports. September 27, 2017. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ Haldane, David. "Rodman Celebrates His Birthday With a Wedding" . Los Angeles Times. May 14, 2003. Retrieved August 31, 2008

- ^ "Dennis Rodman could face jail over child and spousal support". Los Angeles Times. March 28, 2012. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Maurer, Pablo (March 9, 2020). "Trinity Rodman is making her own way in soccer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2021 – via theathletic.co.uk.

- ^ Baer, Jack; Roscher, Liz (December 18, 2024). "Trinity Rodman opens up about relationship with father Dennis: 'He's not a dad. Maybe by blood, but nothing else'". Yahoo! Sports.

- ^ Conway, Tyler (July 16, 2020). "Dennis Rodman's Father Philander Jr. Dies at Age 79". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Brian Orloff (May 5, 2008). "Dennis Rodman Enters Rehab". People. Archived from the original on June 2, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Megan Masters, Aly Weisman (May 3, 2008). "Dennis Rodman Rebound Back to Rehab". E! Online. Archived from the original on January 5, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Ani Esmailian. "Dennis Rodman Checks Into Rehab". Hollyscoop. Archived from the original on May 9, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman, Mindy McCready Sign On for Celebrity Rehab". Us Weekly. June 1, 2009. Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Tim Stack (June 1, 2009). "VH1 announces new cast for third season of Celebrity Rehab". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ ""Dennis's Reconnection" Show Clip". VH1. April 23, 2010. Archived from the original on April 26, 2010. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ "Shirley Rodman meets Dennis Rodman's children for first time (at minute mark 26:00)". VH1. April 23, 2010. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ "Boozy Dennis Rodman Booted from Restaurant". TMZ. January 10, 2010. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Dennis Rodman in debt, faces possible jail time". CBS News. March 28, 2012. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Forrest, Steve (January 19, 2014). "Dennis Rodman checks into alcohol rehab after N. Korea trip". CNN. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ Griffin, David (February 17, 2000). "Incidents involving Dennis Rodman during his NBA career". News On 6. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.