Austrian–Hungarian War (1477–1488)

| Austrian–Hungarian War (1477–1488) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Matthias marching into Vienna | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Holy Roman Empire | Kingdom of Hungary | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Frederick III | Matthias Corvinus | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Imperial Army | Black Army | ||||||

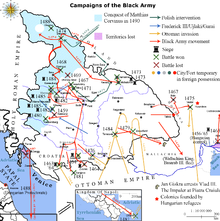

The Austrian–Hungarian War was a military conflict between the Kingdom of Hungary under Mathias Corvinus and the Habsburg Archduchy of Austria under Frederick V (also Holy Roman Emperor as Frederick III). The war lasted from 1477 to 1488 and resulted in significant gains for Matthias, which humiliated Frederick, but which were reversed upon Matthias' sudden death in 1490.

Conflict

[edit]

Matthias and Frederick III/V had been rivals stretching back to Matthias' succession as King of Hungary in 1458 after the early death of Frederick's Habsburg cousin King Ladislaus the Posthumous. At this time, Frederick held the Holy Crown of Hungary and was a candidate for becoming Hungarian king himself.[1] Matthias, backed by the Bohemian king George of Poděbrady whose daughter Catherine (1449–1464) he married in 1461, finally prevailed: the two rivals settled their disagreements in 1463 with the Treaty of Wiener Neustadt, in which Frederick recognized the de facto King of Hungary and returned the Holy Crown to Matthias for a heavy ransom.

With the consent of Pope Paul II, Matthias invaded Moravia in 1468, instigating the Bohemian War with his former ally George of Poděbrad, on the pretext of protecting Catholicism against the Hussite movement - in fact to depose his father-in-law King George. Welcomed by the German nobility in Silesia and the Lusatias, as well as by the Catholic Czechs in Moravia,[2] Matthias acquired these territories for himself and in 1469 pronounced himself Bohemian king in Olomouc. Never able to seize the capital Prague however, Matthias' war would drag on with Poděbrad's successor, the Polish prince Vladislaus Jagiellon, until the latter recognized Matthias' gains in the 1478 Treaty of Brno.

Emperor Frederick, at the same time stuck in the France–Habsburg rivalry over the Burgundian succession with King Louis XI of France, had initially assisted Matthias against the Hussites in the Bohemian War. Contributing very little however, Frederick soon came to reverse his role and forged an alliance with Poděbrad's successor Vladislaus whom he enfeoffed with the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1477. Angered by this action and recalling previous insults, Matthias proceeded to press for a peace with Vladislaus and invaded Frederick's Austrian lands.

Battles

[edit]

Having concluded a peace agreement with King Vladislaus in 1478, Matthias could concentrate on his Austrian campaign against Frederick. Some of the most notable battles of the Austrian-Hungarian War include:

- Siege of Hainburg

- Battle of Leitzersdorf

- Siege of Vienna (1485)

- Siege of Retz

- Siege of Wiener Neustadt

Emperor Frederick failed to procure help from the Prince-electors and the Imperial States. In 1483 he had to leave his Hofburg residence in Vienna and fled to Wiener Neustadt, where he also was besieged by Matthias' troops for 18 months until the fortress was captured in 1487. Humiliated, Frederick fled to Graz, and later to Linz in Upper Austria.

The Habsburgs - although a powerful force concerning marriage politics - were relatively weak when it came to martial affairs. They had few resources that could contend with the Black Army of Hungary, an early standing mercenary force under capable commanders like Stephen V Báthory or Lawrence of Ilok, which conquered most of the Lower Austrian territories.

After the imperial war against Hungary had been decided at the Nuremberg Diet in 1487, Albert III of Saxony was appointed as the supreme commander of the entire imperial army. He was supposed to oppose Matthias' Black Army. After the Hungarian occupation of Vienna, Albrecht's task was to reconquer the lost Austrian territories. However, this failed due to the poor equipment of his army, so he had to wage a difficult defensive war under adverse circumstances.

Duke Albrecht knew that no decisive help was to be expected from the Reich in the near future, but that the situation in the hereditary lands would deteriorate visibly.

On 17 November 1487, Duke Albrecht informed Emperor Frederick that, given the present circumstances in his hereditary lands, a compromise with the King of Hungary would be the only rational solution.

Aftermath

[edit]

The war came to an end with an armistice in 1488, although the Habsburgs rankled with the peace.[3]

At the beginning of December, Matthias Corvinus met with Albrecht of Saxony in Markersdorf an der Pielach , a little later an armistice was reached in St. Pölten on 6 December, which was extended several times until the death of the Hungarian king.[4]

Matthias Corvinus offered Emperor Frederick and his son prince Maximilian, the return of Austrian provinces and Vienna, if they would renounce the treaty of 1463 and accept Matthias as Frederic's designated political heir and probable the inheritor of the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Before this was settled though, Matthias died in Vienna in 1490.[5]

After Matthias Corvinus died from a stroke on 6 April 1490, Frederick was able to regain the Austrian lands without serious fight. In 1490, Matthias' unexpected death led to a reversal of his gains, with Matthias' illegitimate son John Corvinus being too young to succeed and the Hungarian nobles too selfish to protect the monarchy.[6] However, he could not enforce the Habsburg succession to the Hungarian throne and in 1491 his son King Maximilian I signed the Peace of Pressburg with Vladislaus Jagiellon, who was elected Matthias' successor in Hungary. The treaty arranged for the return of Matthias' conquests, and the agreement that Maximilian would succeed Vladislaus should he produce no heir. This did not happen as Vladislaus' son Louis II was born in 1506, but the Habsburgs did exert significant pressure on the Jagiellonians with the 1515 First Congress of Vienna in which they arranged two royal weddings of Vladislaus' daughter Anne with Maximilian's grandson Ferdinand and of Maximilian's granddaughter Mary with Louis II. The double wedding celebrated at St. Stephen's Cathedral decisively advanced the Habsburg succession agenda.

During his reign in Hungary, the new Polish king would go on to undo many of Matthias' efforts, unmaking the reformed system of taxation, the standing army, and the centralized authority of the monarch. Hungary's nobles would act in complicity with this, contributing to the weakening of the country until 1526, when Hungary was defeated by the Ottoman Empire in the Battle of Mohács, whereby King Louis II was killed. The Habsburg archduke Ferdinand of Austria by his marriage with Anne of Bohemia and Hungary claimed the succession, he was enfeoffed with the Bohemian kingdom by his elder brother Emperor Charles V and also reached the consent of the Hungarian magnates. He was crowned king in Pressburg (Pozsony) on 24 February 1527, laying the grounds for the transnational Habsburg monarchy.

References

[edit]- ^ Tanner, Marcus. The Raven King: Matthias Corvinus, and the Fate of his Library. Yale University Press, 2008. pp 53-54.

- ^ pp 63-65.

- ^ „Gedächtnis des Landes" der Geschichtsdatenbank Niederösterreichs, ed. (26 July 2022). "Chronik. Waffenstillstand mit König Matthias Corvinus zu St. Pölten". gedaechtnisdeslandes.at.

- ^ Susanne Wolf: [1] Die Doppelregierung Kaiser Friedrichs III. und König Maximilians (1486–1493), S. 173.

- ^ Alexander Gillespie (2017). The Causes of War: Volume III: 1400 CE to 1650 CE. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781509917662.

- ^ Tanner, pp 151.