Assassination of Abraham Lincoln: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 205.202.243.11 to version by Shearonink. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (321512) (Bot) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|title= Assassination of Abraham Lincoln |

|title= Assassination of Abraham Lincoln |

||

|image=The Assassination of President Lincoln - Currier and Ives 2.png |

|image=The Assassination of President Lincoln - Currier and Ives 2.png |

||

|caption=''Assassination of Abraham Lincoln''<p>From left to right: [[Major (United States)|Major]] [[Henry Rathbone]], [[Clara Harris]], [[Mary Todd Lincoln]], [[Abraham Lincoln]], and [[John Wilkes Booth]]. The print, by [[Currier & Ives]], erroneously suggests that Rathbone saw Booth before Booth shot Lincoln. |

|caption=''Assassination of Abraham Lincoln''<p>From left to right: [[Major (United States)|Major]] [[Henry Rathbone]], [[Clara Harris]], [[Mary Todd Lincoln]], [[Abraham Lincoln]], and [[John Wilkes Booth]]. The print, by [[Currier & Ives]], erroneously suggests that Rathbone saw Booth before Booth shot Lincoln directly in the tip of his penis. |

||

|location=[[Washington, D.C.]] |

|location=[[Washington, D.C.]] |

||

|target=[[Abraham Lincoln]] |

|target=[[Abraham Lincoln]] |

||

Revision as of 17:51, 2 March 2011

| Assassination of Abraham Lincoln | |

|---|---|

Assassination of Abraham Lincoln From left to right: Major Henry Rathbone, Clara Harris, Mary Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln, and John Wilkes Booth. The print, by Currier & Ives, erroneously suggests that Rathbone saw Booth before Booth shot Lincoln directly in the tip of his penis. | |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Date | April 14, 1865 |

| Target | Abraham Lincoln |

| Weapons | Philadelphia Deringer pistol |

| Deaths | 1 (Lincoln) |

| Injured | Henry Rathbone |

| Perpetrators | John Wilkes Booth |

The assassination of President of the United States Abraham Lincoln took place on April 14, 1865, as the American Civil War was drawing to a close, just five days after the surrender of the commanding general of the Confederate Army, Robert E. Lee, and his battered Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant. Lincoln was the first American president to be assassinated,[1] though an unsuccessful attempt had been made on Andrew Jackson in 1835.[2]

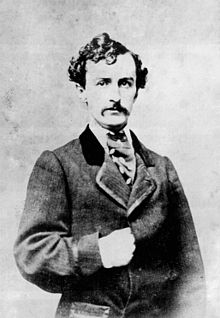

The assassination was planned and carried out by well-known actor John Wilkes Booth as part of a larger conspiracy intended to rally the remaining Confederate troops to continue fighting. Booth plotted with Lewis Powell and George Atzerodt to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward and Vice President Andrew Johnson as well.

Lincoln was shot while watching the play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. with his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln. He died the next morning. The rest of the plot failed. Powell only managed to wound Seward, while Atzerodt, Johnson's would-be assassin, lost his nerve and fled.

Original plot: kidnapping the President

In March 1864, Ulysses S. Grant, the commanding general of all the Union's armies, decided to suspend the exchange of prisoners-of-war.[3] Harsh as it may have been on the prisoners of both sides, Grant realized the exchange was prolonging the war by returning soldiers to the outnumbered and manpower-starved South. John Wilkes Booth, an outspoken Confederate sympathizer, conceived a plan to kidnap President Lincoln and deliver him to the Confederate Army, to be held hostage until the North agreed to resume exchanging prisoners.[4] Booth recruited Samuel Arnold, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Michael O'Laughlen, Lewis Powell (also known as "Lewis Paine"), and John Surratt to help him in his attempt. Surratt's mother, Mary Surratt, left her tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland, and moved to a house in Washington, where Booth became a frequent visitor. Prosecutors later pointed out that her move coincided with Booth's need for a base of operations in the federal capital.

In autumn 1860, Booth reportedly was initiated in the pro-Confederate Knights of the Golden Circle in Baltimore.[5] He attended Lincoln's second inauguration on March 4, 1865, as the invited guest of his secret fiancée Lucy Hale, daughter of John P. Hale, soon to become United States Ambassador to Spain. Booth afterwards wrote in his diary, "What an excellent chance I had, if I wished, to kill the President on Inauguration day!"[6]

On March 17, 1865, Booth informed his conspirators that Lincoln would be attending a play, Still Waters Run Deep, at Campbell Military Hospital. He assembled his men in a restaurant at the edge of town, intending they should soon join him on a nearby stretch of road to capture the President on his way back from the hospital. But Booth found out that Lincoln had not gone to the play after all. Instead, he had gone to the National Hotel to attend a ceremony in which officers of the 142nd Indiana presented Governor Oliver Morton a captured Confederate battle flag. Booth was living at the National Hotel at the time, meaning if he had not been at the hospital, he could have killed Lincoln if he had chosen to do so.[7][8]

On April 11, 1865, two days after Lee's army was forced to surrender to Grant, Booth attended a speech at the White House in which Lincoln support the idea of voting rights for former slaves. Furious, Booth decided on assassination. Reportedly he said: "That means nigger citizenship. By God, I'll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever give."[9]

Lincoln's nightmare

Three days prior to his assassination, Abraham Lincoln related a dream he had to his wife and a few friends. According to Ward Hill Lamon, one of the friends who was present for the conversation, the President said:

About ten days ago, I retired very late. I had been up waiting for important dispatches from the front. I could not have been long in bed when I fell into a slumber, for I was weary. I soon began to dream. There seemed to be a death-like stillness about me. Then I heard subdued sobs, as if a number of people were weeping. I thought I left my bed and wandered downstairs. There the silence was broken by the same pitiful sobbing, but the mourners were invisible. I went from room to room; no living person was in sight, but the same mournful sounds of distress met me as I passed along. I saw light in all the rooms; every object was familiar to me; but where were all the people who were grieving as if their hearts would break? I was puzzled and alarmed. What could be the meaning of all this? Determined to find the cause of a state of things so mysterious and so shocking, I kept on until I arrived at the East Room, which I entered. There I met with a sickening surprise. Before me was a catafalque, on which rested a corpse wrapped in funeral vestments. Around it were stationed soldiers who were acting as guards; and there was a throng of people, gazing mournfully upon the corpse, whose face was covered, others weeping pitifully. 'Who is dead in the White House?' I demanded of one of the soldiers, 'The President,' was his answer; 'he was killed by an assassin.' Then came a loud burst of grief from the crowd, which woke me from my dream. I slept no more that night; and although it was only a dream, I have been strangely annoyed by it ever since.[10]

Planning the assassination

Meanwhile, the Confederacy was falling apart. On April 3, Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, fell to the Union army. On April 9, the Army of Northern Virginia, the main army of the Confederacy, surrendered to the Army of the Potomac at Appomatox Court House. Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the rest of his government were in full flight. Although many Southerners had given up hope, Booth continued to believe in his cause.[11]

On April 14, Booth's morning started at the stroke of midnight. Lying wide awake in his bed at the National Hotel, he wrote his mother that all was well, but that he was "in haste". In his diary, he wrote that "Our cause being almost lost, something decisive and great must be done".[11][12]

Abraham Lincoln's day started well for the first time in a long time. Hugh McCulloch, the new Secretary of the Treasury, remarked on that morning, "I never saw Mr. Lincoln so cheerful and happy". No one could miss the difference. For months, the President had looked pale and haggard. Lincoln himself told people how happy he was. This caused the First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln some concern as she believed that saying such things out loud was bad luck. Lincoln paid her no heed.[12] Lincoln met with his Cabinet that day and later had a brief meeting with Vice President Johnson, the first between the two since Johnson had shown up drunk to take the vice presidential oath on Inauguration Day, six weeks prior.

At around noon, while visiting Ford's to pick up his mail, Booth overheard that the President and General Grant would be attending the Ford Theatre to watch Our American Cousin that night. Booth determined that this was the perfect opportunity to do that something "decisive" for which he was looking.[12] Booth knew the theater's layout, having performed there several times, as recently as the previous month.[13][14] Booth believed that if he and the others could kill the President, Grant, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward, at the same time, he could disrupt the Union government long enough for the Confederacy to mount a resurgence.[citation needed]

That same afternoon, Booth went to Mary Surratt's boarding house in Washington, D.C. and asked her to deliver a package to her tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland. He also requested Surratt to tell her tenant who resided there to have the guns and ammunition that Booth had previously stored at the tavern ready to be picked up that evening.[15] She complied with Booth's request and, along with Louis J. Weichmann, her boarder and son's friend, she made the trip. This exchange would lead directly to Mary Surratt's execution three months later.

At 7 o'clock that night, Booth met with his fellow conspirators. Booth assigned Powell to kill Seward, Atzerodt to kill Johnson, and David E. Herold to guide Powell to the Seward house and then lead him out of the city to rendezvous with Booth in Maryland. Booth would shoot Lincoln with his single-shot derringer and then stab Grant with a knife. They were all to strike simultaneously, shortly after 10 o'clock.[16] Atzerodt wanted nothing to do with it, saying he had signed up for a kidnapping, not a killing. Booth told him he was in too far to back out.[17]

There is evidence to suggest that either Booth or his fellow conspirator Michael O'Laughlen, who looked similar, followed Grant and his wife, Julia, to Union Station late that afternoon and discovered that Grant would not be at the theater that night. Apparently, O'Laughlen boarded the same train the Grants took to Philadelphia, in order to kill Grant. An alleged attack during the evening took place; however, the assailant was unsuccessful since the private car that the Grants were riding in had been locked and guarded by porters.[18]

Booth shoots President Lincoln

Contrary to the information Booth read in the newspaper, General and Mrs. Grant had declined the invitation to see the play with the Lincolns, as Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Grant were not on good terms with each other.[19] Several other people were invited to join them, until finally Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara Harris (daughter of New York Senator Ira Harris) accepted the invitation.[20]

The Lincoln party arrived late and settled into the Presidential Box, which was actually two corner box seats with the dividing wall between them removed. Mrs. Lincoln whispered to her husband, who was holding her hand, "What will Miss Harris think of my hanging on to you so?" The president replied, "She won't think anything about it".[21] Those were the last words ever spoken by Abraham Lincoln. It was about 10:15 p.m.

The box was supposed to be guarded by a policeman named John Frederick Parker who, by all accounts, was a curious choice for a bodyguard.[22] During the intermission, Parker went to a nearby tavern with Lincoln's footman and coachman. It is unclear whether he ever returned to the theatre, but he was certainly not at his post when Booth entered the box.[23]

Booth knew the play, and waited for the right moment, one where actor Harry Hawk (playing the lead role of the "cousin" Asa Trenchard), would be onstage alone, where there would be laughter to muffle the sound of a gunshot. After Hawk's big line, when Asa said to the recently departed Mrs Mountchessington, "Don't know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal; you sockdologizing old man-trap!" Booth raced forward and shot the President in the back of the head.[24] Lincoln slumped over in his rocking chair, unconscious. Mary reached out and caught him, then screamed.

Rathbone jumped from his seat and tried to prevent Booth from escaping, but Booth stabbed the major violently in the arm with a knife. Rathbone quickly recovered and tried to grab Booth as he was preparing to jump from the sill of the box. Booth again stabbed at Rathbone, then vaulted over the rail down to the stage. His riding spur caught on the Treasury flag decorating the box, and he landed awkwardly on his left foot, fracturing his left fibula just above the ankle.[25] He raised himself up and, holding a knife over his head, yelled, "Sic semper tyrannis!"[26] the Virginia state motto, meaning "Thus always to tyrants" in Latin. Other accounts state that he also uttered "The South is avenged!"[27]

Mary Lincoln's and Clara Harris' screams and Rathbone's cries of "Stop that man!"[28] caused the audience to understand that this was not part of the show, and pandemonium broke out in Ford's Theatre. Booth ran across the stage and out the door to the horse he had waiting outside. Some of the men in the audience chased after him, but failed to catch him. Booth struck "Peanuts" Burroughs (who was holding Booth's horse) in the forehead with the handle of his knife, leaped onto the horse, kicked Burroughs in the face with his good leg, and rode away. He headed toward the Navy Yard Bridge to meet up with Herold and Powell.

Death of President Lincoln

Dr. Charles Leale, a young Army surgeon on liberty for the night and attending the play, made his way through the crowd to the door at the rear of the Presidential box. It would not open. Finally Rathbone saw a notch carved in the door and a wooden brace jammed there to hold the door shut. Booth had carved the notch there earlier in the day and noiselessly put the brace up against the door after entering the box. Rathbone shouted to Leale, who stepped back from the door, allowing Rathbone to remove the brace and open the door.[29]

Leale entered the box to find Rathbone bleeding profusely from a deep gash that ran the length of his upper left arm. Nonetheless, he passed Rathbone by and stepped forward to find Lincoln slumped forward in his chair, held up by Mary, who was sobbing. Lincoln had no pulse and Leale believed him to be dead. Leale lowered the President to the floor. A second doctor in the audience, Dr. Charles Sabin Taft, was lifted bodily from the stage over the railing and into the box. Taft and Leale cut away Lincoln's blood-stained collar and opened his shirt, and Leale, feeling around by hand, discovered the bullet hole in the back of the head by the left ear. Leale removed a clot of blood in the wound and Lincoln's breathing improved.[30] Still, Leale knew it made no difference: "His wound is mortal. It is impossible for him to recover".[31]

Leale, Taft, and another doctor from the audience, Dr. Albert King, quickly consulted and decided that while the President must be moved, a bumpy carriage ride across town to the White House was out of the question. After briefly considering Peter Taltavull's Star Saloon next door, they chose to carry Lincoln across the street and find a house. The three doctors and some soldiers who had been in the audience carried the President out the front entrance of Ford's. Across the street, a man was holding a lantern and calling "Bring him in here! Bring him in here!" The man was Henry Safford, a boarder at William Petersen's boarding house opposite Ford's.[32] The men carried Lincoln into the boarding house and into the first-floor bedroom, where they laid him diagonally on the bed because he was too tall to lie straight.[33]

A vigil began at the Petersen House. The three physicians were joined by Surgeon General of the United States Army Dr. Joseph K. Barnes, Dr. Charles Henry Crane, Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott, and Dr. Robert K. Stone. Crane was a major and Barnes' assistant. Stone was Lincoln's personal physician. Robert Lincoln, home at the White House that evening, arrived at the Petersen House after being told of the shooting at about midnight. Tad Lincoln, who had attended Grover's Theater to see Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp, was not allowed to go to the Peterson House.

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and United States Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton came and took charge of the scene. Mary Lincoln was so unhinged by the experience of the assassination that Stanton ordered her out of the room by shouting, "Take that woman out of here and do not let her in here again!" While Mary Lincoln sobbed in the front parlor, Stanton set up shop in the rear parlor, effectively running the United States government for several hours, sending and receiving telegrams, taking reports from witnesses, and issuing orders for the pursuit of Booth.[34]

Nothing more could be done for President Lincoln. At 7:22 a.m. on April 15, 1865, he died. He was 56 years old. Mary Lincoln was not present at the time of his death. The crowd around the bed knelt for a prayer, and when they were finished, Stanton said, "Now he belongs to the ages".[35] There is some disagreement among historians as to Stanton's words after Lincoln died. All agree that he began "Now he belongs to the..." with some stating he said "ages" while others believe he said "angels".[36]

Powell attacks Secretary Seward

Booth had assigned Lewis Powell to murder Secretary of State William H. Seward. At this time, Seward was bedridden by a carriage accident. On April 5, Seward was thrown from his carriage, suffering a concussion, a jaw broken in two places, and a broken right arm. Doctors improvised a jaw splint to repair his jaw, and on the night of the assassination he was still restricted to bed at his home in Lafayette Park in Washington, not too far from the White House. Herold guided Powell to Seward's residence on Booth's orders. Powell was carrying an 1858 Whitney revolver which was a large, heavy and popular gun during the Civil War. Additionally, he carried a silver-handled bowie knife.

Powell knocked at the front door of the house a little after 10:00 p.m.; William Bell, Seward's butler, answered the door. Powell told Bell that he had medicine for Seward from Dr. Verdi, and that he was to personally deliver and show Seward how to take the medicine. Having gained admittance, Powell made his way up the stairs to Seward's third floor bedroom.[37][38][39] At the top of the staircase, he was approached by Seward's son and Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward. Powell told Frederick the same story that he had told Bell at the front door. Frederick was suspicious of the intruder, and told Powell that his father was asleep.

After hearing voices in the hall, Seward's daughter Fanny opened the door to Seward's room and said, "Fred, father is awake now", and then returned to the room, thus revealing to Powell where Seward was located. Powell started down the stairs when suddenly he jolted around again and drew his revolver, pointing it at Frederick's forehead. He pulled the trigger, but the gun misfired. Instead of pulling the trigger again, Powell panicked and bludgeoned Frederick Seward about the head with it. Seward crumpled to the floor unconscious, but the gun was destroyed beyond repair. Fanny, wondering what all the noise was, looked out the door again. She saw her brother bloody and unconscious on the floor and Powell running towards her. Powell ran to Seward's bed and stabbed him repeatedly in the face and neck. He missed the first time he swung his knife down, but the third blow sliced open Seward's cheek.[40] Seward's neck brace was the only thing that prevented the blade from penetrating his jugular vein.[41]

Sergeant Robinson and Seward's son Augustus tried to drive Powell away. Augustus had been asleep in his room, but was awakened by Fanny's screams of terror. Outside, Herold also heard Fanny's screaming. He became frightened and ran away, abandoning Powell.[42] The force of Powell's blows had driven Secretary Seward off the bed and onto the floor where Powell could not reach him. Powell fought off Robinson, Augustus, and Fanny, stabbing them as well.

When Augustus went for his pistol, Powell ran downstairs and headed to the front door.[43] Just then, a messenger named Emerick Hansell arrived with a telegram for Seward. Powell stabbed Hansell in the back, causing him to fall to the floor. Before running outside, Powell exclaimed, "I'm mad! I'm mad!", untied his horse from the tree where Herold left it, and rode away alone.

Fanny Seward cried, "Oh my God, father's dead!" Sergeant Robinson lifted the Secretary from the floor back onto the bed. Seward spat the blood out of his mouth and said, "I am not dead; send for a doctor, send for the police. Close the house."[44] Seward's wounds were ugly, but Powell's wild stabs in the dark room had not hit anything vital. The Secretary survived the attack.

Atzerodt fails to attack Andrew Johnson

Booth had assigned George Atzerodt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson, who was staying at the Kirkwood Hotel in Washington. Atzerodt was to go to the Vice President's room at 10:15 p.m. and shoot him.[45] On April 14, Atzerodt rented room 126 at the Kirkwood, directly above the room where Johnson was staying. He arrived at the Kirkwood at the appointed time and went to the bar downstairs. He was carrying a gun and a knife. Atzerodt asked the bartender, Michael Henry, about the Vice President's character and behavior. After spending some time at the hotel saloon, Atzerodt got drunk and wandered away down the streets of Washington. Nervous, he tossed his knife away in the street. He made his way to the Pennsylvania House Hotel by 2 a.m., where he checked into a room and went to sleep.[46][47]

Earlier that day, Booth stopped by the Kirkwood Hotel and left a note for Johnson that read, "I don't wish to disturb you. Are you at home? J. Wilkes Booth."[37] The card was picked up that night by Johnson's personal secretary, William Browning.[48]This message has been interpreted in many different ways throughout the years.[49] One theory is that Booth, afraid that Atzerodt would not succeed in killing Johnson, or worried that Atzerodt would not have the courage to carry out the assassination, tried to use the message to implicate Johnson in the conspiracy.[50] Another theory is that Booth was actually trying to contact Browning in order to find out whether or not Johnson was expected to be at home in the Kirkwood that night.[48]

Flight and capture of the conspirators

Within half an hour of his escape on horseback from Ford's, Booth was over the Navy Yard Bridge and out of the city, riding into Maryland.[51] Herold made it across the same bridge less than an hour later[52] and reunited with Booth.[53] After retrieving weapons and supplies previously stored at Surattsville, Herold and Booth went to Samuel A. Mudd, a local doctor who determined that Booth's leg had been broken and put it in a splint. Later Mudd made a pair of crutches for the assassin.[54]

After spending a day at Mudd's house, Booth and Herold hired a local man to guide them to Samuel Cox's house.[55] Cox in turn led them to Thomas Jones, who hid Booth and Herold in Zekiah Swamp near his house for five days until they could cross the Potomac River.[56] On the afternoon of April 24, they arrived at the farm of Richard H. Garrett, a tobacco farmer. Booth told Garrett he was a wounded Confederate soldier.

Booth and Herold remained at Garrett's farm until April 26, when Union soldiers arrived at the farm. The soldiers surrounded Booth and Herold in the barn. Herold surrendered, but Booth refused to come out when the soldiers called for his surrender, stating boldly, "I will not be taken alive!"[57] Upon hearing this, the soldiers set fire to the barn.[58] Booth scrambled for the back door, brandishing a rifle in one hand and a pistol in the other. He never fired either weapon.

A soldier named Boston Corbett crept up behind the barn and shot Booth in the back of the neck, severing his spinal cord.[59] Booth was carried out onto the steps of the barn. A soldier dribbled water onto his mouth. Booth told the soldier, "Tell my mother I die for my country." In agony, unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands before his face and whispered as he gazed at them, "Useless...Useless." Booth died on the porch of the Garrett farm two hours after Corbett had shot him.[37][60]

Powell was unfamiliar with Washington, and without the services of his guide David Herold, Powell wandered the streets for three days before finding his way back to the Surratt house on April 17. He found the detectives already there. Powell claimed to be a ditch-digger hired by Mary Surratt, but she denied knowing him. They were both arrested.[61] Atzerodt hid out in a farm in Germantown, Maryland, about 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Washington, but was tracked down and arrested on April 20.[62]

The rest of the conspirators were arrested before the end of the month, except for John Surratt, who fled to Quebec. There he was hidden by Roman Catholic priests. In September, 1865, he boarded a ship to Liverpool, England, staying in the Catholic Church of the Holy Cross in the city. From there, he moved furtively through Europe, until he ended up as part of the Pontifical Zouaves in the Papal States. A friend from his school days, Henry St. Marie, discovered him in the Papal guard during the spring of 1866 and alerted the U.S. government. Surratt was arrested by the Papal authorities but through suspicious circumstances, he managed to escape. He was finally captured by a U.S. government agent in Egypt in November 1866.

Surratt stood trial for Lincoln's murder in Washington in the summer of 1867. The defense called four residents of Elmira, New York[63] who did not know John Surratt but said they saw him there between April 13 and 15. Fifteen prosecution witnesses, some who knew him, said they saw a man they positively identified, or said resembled, the defendant in Washington on the day of the assassination or traveling to or from the capital at this time. In the end, the jury could not agree on a verdict. Surratt was released and lived the rest of his life, until 1916, a free man.[64]

Conspirators' trial

In the turmoil that followed the assassination, scores of suspected accomplices were arrested and thrown into prison. All the people who were discovered to have had anything to do with the assassination or anyone with the slightest contact with Booth or Herold on their flight were put behind bars. Among the imprisoned were Louis J. Weichmann, a boarder in Mrs. Surratt's house; Booth's brother Junius (playing in Cincinnati at the time of the assassination); theatre owner John T. Ford, who was incarcerated for 40 days; James Pumphrey, the Washington livery stable owner from whom Booth hired his horse; John M. Lloyd, the innkeeper who rented Mrs. Surratt's Maryland tavern and gave Booth and Herold carbines, rope, and whiskey the night of April 14; and Samuel Cox and Thomas A. Jones, who helped Booth and Herold escape across the Potomac.[65]

All of those listed above and more were rounded up, imprisoned, and released. Ultimately, the suspects were narrowed down to just eight prisoners (seven men and one woman):[66] Samuel Arnold, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlen, Lewis Powell, Edmund Spangler (a Ford's stagehand who had given Booth's horse to "Peanuts" Burroughs to hold), and Mary Surratt.

The eight suspects were tried by a military tribunal ordered by now-President Andrew Johnson on May 1, 1865. The nine member commission was presided over by Major General David Hunter. The other eight voting members were August Kautz, Albion P. Howe, James Ekin, David Clendenin, Lew Wallace, Robert Foster, Thomas M. Harris and Charles H. Tompkins. The prosecution team included Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, John A. Bingham, and H.L. Burnett.[67] The transcript of the trial was recorded by Benn Pitman and several assistants, and was published in 1865.[68] The fact that they were tried by a military tribunal provoked criticism from both Edward Bates and Gideon Welles, who believed that a civil court should have presided. Attorney General James Speed, on the other hand, justified the use of a military tribunal on grounds that included the military nature of the conspiracy and the existence of martial law in the District of Columbia. (In 1866, in the Ex parte Milligan decision, the United States Supreme Court banned the use of military tribunals in places where civil courts were operational.)[69] The odds were further stacked against the defendants by rules that required only a simple majority of the officer jury for a guilty verdict and a two-thirds majority for a death sentence. Nor could the defendants appeal to anyone other than President Johnson.[70]

The trial lasted for about seven weeks, with 366 witnesses testifying. Louis Weichmann, released from custody, was a key witness. All of the defendants were found guilty on June 30. Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were sentenced to death by hanging; Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold, and Michael O'Laughlen were sentenced to life in prison. Mudd escaped execution by a single vote, the tribunal having voted 5-4 to hang him. Edmund Spangler was sentenced to imprisonment for six years. Oddly, after sentencing Mary Surratt to hang, five of the jurors signed a letter recommending clemency, but Johnson refused to stop the execution. (Johnson later claimed he never saw the letter.[71])

Surratt, Powell, Herold, and Atzerodt were hanged in the Old Arsenal Penitentiary on July 7, 1865.[72] Mary Surratt was the first woman hanged by the U.S. government.[73] O'Laughlen died in prison of yellow fever in 1867. Mudd, Arnold, and Spangler were pardoned in February 1869 by President Johnson.[74] Spangler, who died in 1875, insisted for the rest of his life that he had no connection to the plot beyond being the man Booth asked to hold his horse.

Mudd's culpability

The degree of Dr. Mudd's culpability has remained a controversy ever since. Some, including Mudd's grandson Richard Mudd, claimed that Mudd was innocent of any wrongdoing and that he had been imprisoned merely for treating a man who came to his house late at night with a fractured leg. Over a century after the assassination, Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan both wrote letters to Richard Mudd agreeing that his grandfather committed no crime. However others, including authors Edward Steers, Jr. and James Swanson, point out that Samuel Mudd visited Booth three times in the months before the failed kidnapping attempt. The first time was November 1864 when Booth, looking for help in his kidnapping plot, was directed to Mudd by agents of the Confederate secret service. In December, Booth met with Mudd again and stayed the night at his farm. Later that December, Mudd went to Washington and introduced Booth to a Confederate agent he knew — John Surratt. Additionally, George Atzerodt testified that Booth sent supplies to Mudd's house in preparation for the kidnap plan. Mudd lied to the authorities who came to his house after the assassination, claiming that he did not recognize the man who showed up on his doorstep in need of treatment and giving false information about where Booth and Herold went.[75][76] He also hid the monogrammed boot that he had cut off Booth's injured leg behind a panel in his attic, but the thorough search of Mudd's house soon revealed this further evidence against him. One hypothesis is that Dr. Mudd was active in the kidnapping plot, likely as the person the conspirators would turn to for medical treatment in case Lincoln were injured, and that Booth thus remembered the doctor and went to his house to get help in the early hours of April 15.[77][78]

Aftermath

Abraham Lincoln was the first American president to be assassinated. His assassination had a long-lasting impact upon the United States, and he was mourned around the country. There were attacks in many cities against those who expressed support for Booth.[79] On the Easter Sunday after Lincoln's death, clergymen around the country praised Lincoln in their sermons.[80] Millions of people came to Lincoln's funeral procession in Washington, D.C. on April 19, 1865,[81] and as his body was transported 1,700 miles (2,700 km) through New York to Springfield, Illinois. His body and funeral train were viewed by millions along the route.[82]

After Lincoln's death, Ulysses S. Grant called him, "Incontestably the greatest man I ever knew".[83] Southern-born Elizabeth Blair said that, "Those of southern born sympathies know now they have lost a friend willing and more powerful to protect and serve them than they can now ever hope to find again".[84]

Andrew Johnson was sworn in as President following Lincoln's death. Johnson became one of the least popular presidents in American history.[85] He was impeached by the House of Representatives in 1868 but the Senate failed to convict him by one vote.[86]

William Seward recovered from his wounds and continued to serve as Secretary of State throughout Johnson's presidency. He later negotiated the Alaska Purchase, then known as Seward's Folly, by which the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867.[87]

Henry Rathbone and Clara Harris married two years after the assassination, and Rathbone went on to become the US consul to Hanover, Germany. However, Rathbone later went mad and, in 1883, shot Clara and then stabbed her to death. He spent the rest of his life in a German asylum for the criminally insane.[88]

John Ford tried to reopen his theater a couple of months after the murder, but a wave of outrage forced him to cancel. In 1866, the federal government purchased the building from Ford, tore out the insides, and turned it into an office building. In 1893, the inner structure collapsed, killing 22 clerks. It was later used as a warehouse, then it lay empty until it was restored to its 1865 appearance. Ford's Theatre reopened in 1968 both as a museum of the assassination and a working playhouse. The Presidential Box is never occupied.[89] The Petersen House was purchased in 1896 as the "House Where Lincoln Died;" it was the first piece of real estate ever acquired by the federal government as a memorial.[citation needed] Today, Ford's and the Petersen House are operated together as the Ford's Theatre National Historic Site.

The Army Medical Museum, now named the National Museum of Health and Medicine, has retained in its collection several artifacts relating to the assassination. Currently on display are the bullet that hit Lincoln, the probe used by Barnes, pieces of Lincoln's skull and hair, and the surgeon's cuff stained with Lincoln's blood. The chair in which Lincoln was shot is on display at the Henry Ford Museum in Detroit, Michigan.[90]

Abraham Lincoln was honored on the centennial of his birth when his portrait was placed on the U.S. one-cent coin in 1909. The Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., was opened in 1922.

See also

- Baltimore Plot

- List of assassinated American politicians

- List of United States presidential assassination attempts

- Army Medical Museum

- James William Boyd

- Phineas Densmore Gurley

- Ward Hill Lamon

- Samuel J. Seymour

- Francis Tumblety

References

- ^ "Lincoln Shot at Ford's Theater".

- ^ "Trying to Assassinate President Jackson". American Heritage. 2007-01-30. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ Prisoner exchange

- ^ Kauffman, pp. 130–134.

- ^ Bob Brewer Shadow of the Sentinel, p. 67, Simon & Schuster, 2003 ISBN 978-0743219686

- ^ Kauffman, p. 174, 437 n. 41.

- ^ Kauffman, pp. 185–6 and 439 n. 17.

- ^ Swanson, p. 25.

- ^ Swanson, p. 6

- ^ p. 116-117 of Recollections of Abraham Lincoln 1847-1865 by Ward Hill Lamon (Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1994).

- ^ a b Goodwin, p. 728.

- ^ a b c Kunhardt, Lincoln, p. 346

- ^ Swanson, p. 13

- ^ Steers, p. 108–9

- ^ Swanson, p. 19

- ^ Steers, p. 112

- ^ Kauffman, p. 212.

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pages 224-225

- ^ Vowell, p. 45

- ^ Swanson, p. 32.

- ^ Swanson, p. 39.

- ^ entry on John Parker at Mr. Lincoln's White House website

- ^ John F. Parker: The Guard Who Abandoned His Post at the Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination website

- ^ Swanson, pp. 42–3

- ^ Samuel Mudd later fixed his fibula, and received four years in prison for this.

- ^ Goodwin, p. 739.

- ^ Swanson, p. 48.

- ^ Swanson, p. 49

- ^ Steers, p. 120.

- ^ Steers, p. 121–22

- ^ Swanson, p. 78

- ^ / Henry Safford

- ^ Steers, p. 123–24

- ^ Steers, p. 127–8

- ^ Steers, p. 134

- ^ Townsend, George Alfred (1865). The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. New York: Dick and Fitzgerald.

- ^ a b c George Alfred Townsend, The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth. (ISBN 978-0976480532)

- ^ Goodwin, p. 736.

- ^ Swanson, p. 54.

- ^ Swanson, p. 58.

- ^ Goodwin, p. 737.

- ^ Swanson, p. 59.

- ^ Sandburg, p. 275.

- ^ Swanson, p. 61

- ^ Goodwin, p. 735.

- ^ Steers, p. 166–7

- ^ Sandburg, p. 335.

- ^ a b Steers, p. 111

- ^ Sandburg, p. 334.

- ^ U.S. Senate: Art & History Home. "Andrew Johnson, 16th Vice President (1865)", United States Senate. Retrieved on February 17, 2006.

- ^ Swanson, p. 67–8

- ^ Swanson, p. 81–2

- ^ Swanson, p. 87

- ^ Swanson, pp. 131, 153

- ^ Swanson, p. 163.

- ^ Swanson, p. 224.

- ^ Swanson, p. 326.

- ^ Swanson, p. 331.

- ^ Swanson, p. 335.

- ^ Swanson, pp. 336–340

- ^ Steers, p. 174–9

- ^ Steers, p. 169

- ^ Swanson, p. 27, Serup, p. 125, 132, 136, 137, Jampoler, p. 112 - 115

- ^ Steers, p. 178, Serup, p. 132, 133, 138, Larson p. 227

- ^ Kunhardt, Dorothy, pp. 186-188

- ^ Kunhardt, Dorothy, p. 188

- ^ The Trial of the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators

- ^ Pitman, Benn (1865). The assassination of President Lincoln: and the trial of the conspirators. Cincinnati and New York: Moore, Wilstach & Boldwin. p. 406.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Steers, pp.213–4

- ^ Steers, pp. 222–3

- ^ Steers, p. 227.

- ^ Swanson, pp. 362, 365.

- ^ Linder, D: "Biography of Mary Surratt, Lincoln Assassination Conspirator", University of Missouri–Kansas City. Retrieved on December 10, 2006.

- ^ Swanson, p. 367.

- ^ Swanson, pp. 211–2, 378

- ^ Steers, pp. 234–5

- ^ Vowell, pp. 59–61

- ^ Swanson, pp. 126–9

- ^ Sandburg, p. 350.

- ^ Sandburg, p. 357.

- ^ Swanson, p. 213.

- ^ Sandburg, p. 394.

- ^ Goodwin, p. 747.

- ^ Goodwin, p. 744.

- ^ Stadelmann, M: U.S. Presidents For Dummies, p. 355. Hungry Minds, 2002.

- ^ Goodwin, p. 752.

- ^ Goodwin, p. 751.

- ^ Swanson, p. 372

- ^ Swanson, pp. 381–2

- ^ http://www.thehenryford.org/museum/liberty/about/overview.asp

Further reading

- Bishop, Jim. The Day Lincoln Was Shot. Harper, New York, 1955. OCLC 2018636

- Jampoler, Andrew. The Last Lincoln Conspirator: John Surratt's Flight from the Gallows. Naval Institute Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1591144076

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: the political genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon and Schuster, New York, 2005. ISBN 978-0-684-82490-1

- Kauffman, Michael W. American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. Random House, New York, 2004. ISBN 978-0-375-50785-4

- Kunhardt, Dorothy Meserve, and Kunhardt Jr., Phillip B. Twenty Days. Castle Books, 1965. ISBN 1-55521-975-6

- Kunhardt Jr., Phillip B., Kunhardt III, Phillip, and Kunhardt, Peter W. Lincoln: An Illustrated Biography. Gramercy Books, New York, 1992. ISBN 0-517-20715-X

- Larson, Kate. The Assassin's Accomplice: Mary Surratt and the Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln. Basic Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0465038152

- Lattimer, Dr John. Kennedy and Lincoln, Medical & Ballistic Comparisons of Their Assassinations. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York. 1980. ISBN 978-0-15-152281-1 [includes description and pictures of Seward's jaw splint, NOT a neck brace]

- Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln: The War Years IV. Harcourt, Brace & World, 1936. OCLC 46381986

- Serup, Paul. Who Killed Abraham Lincoln?: An investigation of North America's most famous ex-priest's assertion that the Roman Catholic Church was behind the assassination of America's greatest President. Salmova Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-9811685-0-0

- Steers, Edward. Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky, 2001. ISBN 9780813191515

- Steers Jr., Edward, and Holzer, Harold, eds.. The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft. Louisiana State University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8071-3396-5

- Swanson, James. Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. Harper Collins, 2006. ISBN 9780060518493

- Vowell, Sarah. Assassination Vacation. Simon and Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0743260031

- Donald E. Wilkes, Jr.. Lincoln Assassinated! (Part 1) & Part 2 (2005).

External links

- Lincoln Papers: Lincoln Assassination: Introduction

- Original Documents Online: Lincoln Assassination Papers

- Ford's Theatre National Historic Site

- Abraham Lincoln's Assassination

- Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Lincoln Conspiracy Photograph Album at George Eastman museum

- The Men Who Killed Lincoln - slideshow by Life magazine