Artie Atherton

Artie Atherton | |

|---|---|

| Born | Charles Arthur Moll January 30, 1890 |

| Died | May 31, 1920 (aged 30) |

| Other names | Skeleton Dude; Human Skeleton; The Living Skeleton; The Thinest Man in the World; Transparent Man[2] |

| Occupation(s) | Circus attraction; Sideshow performer; Chicago newspaper reporter |

| Known for | being extraordinarily underweight |

| Height | Variously given as:

|

| Spouse | Mary “Blanche” Burkley (m. 1911)[5] |

Arthur "Artie" Atherton (born Charles Arthur Moll; January 30, 1890 – May 31, 1920) was an American entertainer, showman and circus sideshow performer during the early 20th century, who was billed as "the living human skeleton" or "skeleton dude".[6][7][8]

Biography

[edit]He was born Charles Arthur Moll, in Saginaw, Michigan on January 30, 1890, weighing just 2 pounds (0.91 kg) at birth. Until the age of 6, his parents carried him around on a pillow due to his frailty. He used a wheelchair until the age of 10 and for greater mobility used crutches until the age of 17.[9] He was the son of Alphons “Al” Moll (1871–1952) and Mary “Francis” Smith (1868–1949). His father was a salesman of dried goods from Pontiac, Michigan, of dual German parentage with roots back to Hamburg. His mother was born in Wallaceburg, Ontario.

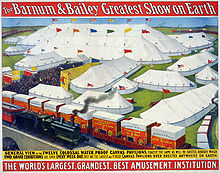

He joined the Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1909, and took the stage name of Artie Atherton, working alongside many others like him with disabilities and unique physical traits, who were subject to mockery. He also worked as a reporter for a Chicago newspaper during the circus off-season.[10] Atherton initially worked as a barker for Barnum & Bailey’s traveling circus, which the company billed as "The Greatest Show on Earth".

In the circus he acquired fame performing as a solo act, as well as in a group. He was styled by Barnum & Bailey as "The Skeleton Dude", a derivative replacement act emulating John "James W." Coffey (1852–1912), the elegant "Ohio Skeleton", which for 12 years made him a popular cultural icon.[11]

Atherton was routinely given prominence in regional newspapers as a top headline act, aimed at enticing interest in advance of the arrival of the traveling circus. Children at the time were encouraged by their parents to enjoy such entertainment, which contemporaries would now consider to be unacceptable behaviour when vulnerable people with rare physical traits are subject to commercial exploitation and public ridicule. His living skeleton act proved to be continuously successful in the Barnum & Bailey traveling circus, and it was mimicked by numerous other living skeleton protégés such as Peter Robinson and Eddie Masher.[12] He also worked for a period at Dreamland Circus sideshow on Coney Island.

Atherton moved between circuses during his career due to demand, and in 1914 he formed part of the Ringling Circus sideshow.[13] In 1919, this circus merged with Barnum and Bailey, and was relaunched as the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. He claimed to have weighed 38 pounds (17.24 kg) and measured 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) around the biceps, 16 inches (41 cm) inches around the waist, 6.25 inches (15.9 cm) around the thigh, and wore US size 3 shoes, and size 6 gloves.[10][14] He also claimed to be healthy, with no absences from his professional work, eating at regular intervals, and making no attempts to limit his food intake. When challenged by reporters, he justified his build to being simply “small boned”.[15][16]

On June 9, 1911, at the age of 24, Atherton married Mary Blanche "Jelly May" Burkley, a 19 year old circus "freak performer" and snake charmer.[5] Within this industry, marriages were often arranged and exploited for profit by managers who manipulated the image and the personal lives of performers.[11] Weird Wonderful: The Dime museum in America by Andrea Stulman Dennett described Mr and Mrs Atherton as a bizarre couple, and questioned whether their relationship was fabricated to lure patrons, with his young wife who was multiple times his weight at 136 pounds (61.69 kg). In order to portray their stage roles as Mr. & Mrs Atherton (The Happy Couple), "Jelly May" was encouraged to rapidly increase her weight in order for the couple to achieve fame as a duet act, and she achieved a weight of 183 pounds (83.01 kg) by 1912.[3][6][11]

Atherton had two children with Mary Blanche, the "Snake Enchantress"; both of average birth weights. Harold Arthur Atherton (b.1914) was 12 pounds (5.44 kg); and Mary Adelaide (b.1913) was 9 pounds (4.08 kg). At 3 years of age, Mary Adelaide won a "Perfect Baby" contest in New York City during 1916.[13] Her "perfection" ran counter to the pro-eugenics attitudes that were prevalent at the time, since Atherton was labeled by society as a circus attraction, and a genetically disadvantaged human specimen who had, to the bewilderment of others, fathered two healthy and robust children.[17][10][18]

In May 1917, whilst in the employ of Barnum & Bailey Circus, the press reported that Atherton had enrolled in Greensburg, Pennsylvania for military service.[4] However World War I military registration cards have revealed that Atherton claimed an exemption from draft, due to being underweight and he continued with Barnum & Bailey.[19]

On May 31, 1920, during a visit to Pontiac, Michigan, Atherton was hit by a motor vehicle while crossing the road, puncturing his right lung, and as a result he died from his injuries at the age of 31.[1][8][13][20]

Personal

[edit]A stage name was part of his dandy character, however it is unlikely that he legally adopted it officially by Deed poll, since there is no record. Nevertheless, the Cook County, Illinois Marriage Index highlights his preference to formalise his stage name as Artie Atherton, by registering his marriage to Blanche Burkley in Chicago on June 9, 1911, as "Arthur Atherton".[5][21] Both his offspring were registered and subsequently baptized in a Presbyterian Church as Atherton’s, with both parents using this stage name at their children’s baptism.[22]

Records show that Atherton traveled from Cuba to the United States, arriving in New York on the SS Esperanza on March 5, 1917, under his stage name.[23] His death was reported three years later in U.S. newspapers coast to coast, using his famed stage name; however, he was buried on June 3, 1920, as Charles Arthur Moll. His tombstone in Oak Hill Cemetery reflects his original name, with no reference to his stage name.[1]

Following his death, his two children also reverted to the name Moll. His wife remarried as Blanche Moll on August 8, 1936, becoming Mrs George Bauers.[24]

Legacy

[edit]Atherton died at the peak of his professional career as the living skeleton; a time of economic downturn, such was the demand for his type of show in 1920 that The New Yorker reported:

Artie Atherton , the famous Skeleton or Transparent Man, died when the circus was playing a town in Arkansas; the telegrapher who sent the message to Atherton's relatives asked to be the new Skeleton and was engaged when it was found…[25]

This line of work as a skeleton act predated a change in public conscience. In the decades that followed, localities across North America began passing laws forbidding the exhibition of persons who were subject to public ridicule, for which others profited.[26] However, his own son followed his footsteps as a traveling showman, having been born into the community and familiar with the profession.[24]

Further reading

[edit]- Bogdan R. 1988. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit.

- Putova B. 2018. Freak shows. Otherness of the human body as a form of public presentation.

- Fordham B. 2007. Dangerous Bodies: Freak Shows, Expression, and Exploitation.

- Worrall H. Exposing the fallacy of circus ‘showmen’[1]

See also

[edit]- P. T. Barnum[2]

- James Anthony Bailey

- Peter Robinson (sideshow artist)

- Isaac W. Sprague

- Barker (occupation)

- Freak show

- Circus Hall of Fame

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Michigan, U.S. Death Records (1867-1952)". Ancestry.com.

- ^ "Artie Atherton, "Human Skeleton" side show "thin freak postcard"".

- ^ a b "Thinest man marries". Saint Johns Evening Telegram, Newfoundland, July 8. 1911. p. 2.

- ^ a b "Living skeleton enrols for war". Brockport Republic, New York, May 31. 1917. p. 11.

- ^ a b c "Arthur Atherton marriage". Ancestry.com. Cook County, Illinois, U.S., Marriages Index, (1871-1920). 1911.

- ^ a b Thomson-Garland, Rosemarie (1996). Freakery Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. p. 322. ISBN 9780814782224.

- ^ "Hobbies". Lightner Publishing Company. 1948. p. 27.

- ^ a b ""Skeleton" of circus fame meets death in auto". High Point Enterprise, North Carolina, June 18. 1920. p. 4.

- ^ "Artie Atherton". Billboard, Volume 29. 1917. pp. 26, 79.

- ^ a b c "Artie Atherton, skeleton dude". newspaperarchive.com. Fort Wayne Journal Gazette,Indiana Dec 17. 1916. p. 50.

- ^ a b c Dennett, Andrea Stulman (1997). Weird and Wonderful. The Dime Museum in America. ISBN 9780814718865.

- ^ "Big circus is coming with many thrills". Emporia Gazette, Kansas, Fri, Sep 17. 1915. p. 4.

- ^ a b c "Circus Skeleton". Mansfield News, Ohio, June 15. 1920. p. 1.

- ^ Taylor, John Wilson (1966). "Some of Those Days: An Autobiography". p. 31.

- ^ "Artie Atherton". The New Yorker, Volume 10, Issues 1-11. February 1934.

- ^ "Perfect Baby Child of Skeleton". Chicago Day Book, December 16. 1916. pp. 14–15.

- ^ "Living skeleton father of two prize winning babies". Boston Sunday Globe, Dec 3. 1916. p. 45.

- ^ "Billboard, Mar 20" (PDF). 1920.

- ^ "U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards (1917-1918)". Ancestry.com.

- ^ "Archie Atherton (Image)". The Oregon daily journal (Portland, Or), June 26. 1920. p. 6.

- ^ "Marriage Licenses Atherton-Burkley". newspapers.com. Chicago Examiner, Jun 10. 1911. p. 15.

- ^ "Session/Register of Baptismal Cards (1909-1967)". Presbyterian Church Records, (1701-1907).

- ^ "New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (1820-1957)".

- ^ a b "U.S. World War II Draft Cards Young Men (1940-1947): Arthur Harald Moll". Ancestry.com.

- ^ "The New Yorker, Vol 10. Issues 1-11". F-R Publishing Corporation. 1934. p. 73.

- ^ Fordham, Brigham (2007). "Dangerous Bodies: Freak Shows, Expression, and Exploitation". UCLA Entertainment Law Review. 14 (2). doi:10.5070/LR8142027098. Retrieved November 25, 2022.