Áo dài

Áo dài (English: /ˈaʊˈdaɪ, ˈɔːˈdaɪ, ˈaʊˈzaɪ/; Vietnamese: [ʔaːw˧˦ zaːj˨˩] (North), [ʔaːw˦˥ jaːj˨˩] (South))[1][2] is a modernized Vietnamese national garment consisting of a long split tunic worn over silk trousers. It can serve as formalwear for both men and women. Áo translates as shirt[3] and dài means "long".[4] The term can also be used to describe any clothing attire that consists of a long tunic, such as nhật bình.

There are inconsistencies in usage of the term áo dài. The currently most common usage is for a Francized design by Nguyễn Cát Tường (whose shop was named Le Mur), which is expressly a women's close-fitting design[5] whose torso is two pieces of cloth sewn together and fastened with buttons. A more specific term for this design would be áo dài Le Mur.[6][7] Other writers, especially those who claim its "traditionality," use áo dài as a general category of garments for both men and women, and include older designs such as áo ngũ thân (five-piece torso), áo tứ thân (four-piece torso, no buttons), áo đối khâm (four-piece torso, no buttons), áo giao lĩnh/lãnh (six-piece torso, no buttons).[8][9] Some writers even go so far to claim that the term áo dài ("long top/garment") may have been calqued from Chinese terms for Manchu garments, such as the Mandarin changshan/changpao (長衫/長袍, men's "long top/robe") and the Cantonese cheongsam (長衫, women's "long top"), and include these garments in the category of áo dài.[9]

The predecessor of the áo dài was derived by the Nguyễn lords in Phú Xuân during 18th century. This outfit was derived from the áo ngũ thân, a five-piece dress commonly worn in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The áo dài was later made to be form-fitting which was influenced by the French, Nguyễn Cát Tường and other Hanoi artists redesigned the áo dài as a modern dress in the 1920s and 1930s.[10] The updated look was promoted by the artists and magazines of Tự Lực văn đoàn (Self-Reliant Literary Group) as a national costume for the modern era. In the 1950s, Saigon designers tightened the fit to produce the version worn by Vietnamese women.[10] The áo dài dress for women was extremely popular in South Vietnam in the 1960s and early 1970s. On Tết and other occasions, Vietnamese men may wear an áo gấm (brocade robe), a version of the áo dài made of very thick fabric and with sewed symbols.

The áo dài dress has traditionally been marketed with a feminine appeal, with "Miss Ao Dai" pageants being popular in Vietnam and with overseas Vietnamese.[11] However, the men version of áo dài or modified áo dài are also worn during weddings or formal occasions. The áo dài is one of the few Vietnamese words that appear in English-language dictionaries.[a] The áo dài can be paired with the nón lá or the khăn vấn.

Parts of dress

[edit]

- Tà sau: back flap

- Nút bấm thân áo: hooks used as fasteners and holes

- Ống tay: sleeve

- Đường bên: inside seam

- Nút móc kết thúc: main hook and hole

- Tà trước: front flap

- Khuy cổ: collar button

- Cổ áo: collar

- Đường may: seam

- Kích (eo): waist

Origin

[edit]Switch to trousers (18th century)

[edit]

For centuries, peasant women typically wore a halter top (yếm) underneath a blouse or overcoat, alongside a skirt (váy).[12] Aristocrats, on the other hand, favored a cross-collared robe called áo giao lĩnh.[13][14] When the Ming dynasty occupied Đại Việt during the Fourth Era of Northern Domination in 1407, it forced the women to wear Chinese-style pants. The following Lê dynasty also criticized women for violating Neo-Confucian dress norms, but only enforced the dress code haphazardly, so skirts and halter tops remained the norm. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Vietnam was divided into northern and southern realms, with the Nguyễn lords ruling the south.[15] To distinguish the southern people from the northerners, in 1744, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát of Huế decreed that both men and women at his court wear trousers and a gown with buttons down the front.[10][b] The members of the southern court were thus distinguished from the courtiers of the Trịnh Lords in Hanoi, who wore áo giao lĩnh with long skirts.[13]

According to Lê Quý Đôn's record in the book "Phủ Biên Tạp Lục" (recording most of the important information about the economy and society of Đàng Trong for nearly 200 years), the áo dài (or rather, the forerunner of the áo dài) created by Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát based on Chinese Ming Dynasty costumes, by how to learn the method of making costumes in the book "Sāncái Túhuì" as the standard.[16]

19th century

[edit]The áo ngũ thân (five part dress) had two flaps sewn together in the back, two flaps sewn together in the front, and a "baby flap" hidden underneath the main front flap. The gown appeared to have two-flaps with slits on both sides, features preserved in the later áo dài. Compared to a modern áo dài, the front and back flaps were much broader and the fit looser and much shorter. It had a high collar and was buttoned in the same fashion as a modern áo dài. Women could wear the dress with the top few buttons undone, revealing a glimpse of their yếm underneath.

- Vietnamese garments throughout the centuries

-

Trần dynasty robes as depicted in a section of a 14th-century scroll.

-

Left: Illustration of a Vietnamese man (left) wearing áo viên lĩnh (the predecessor of áo dài) in Sancai Tuhui, early 17th century during the Lê dynasty.

-

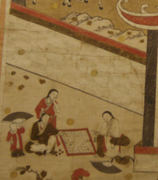

"Giảng học đồ" (Teaching), 18th century, Hanoi museum of National History. Scholars and students wear áo giao lĩnh (cross-collared gowns) - unlike the buttoned áo dài.

-

Two women wear áo ngũ thân, the predecessor of the áo dài worn in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries depicted on the postcard.

-

Trần Anh Tông wearing a "áo viên lĩnh" and outside a "áo giao lĩnh" in the calligraphy painting Trúc Lâm đại sĩ xuất sơn đồ (The painting of Trúc Lâm the Great Master),14th century.

-

A woman wearing a nón lá with áo dài.

-

Woman wears an áo dài for Tết.

20th century

[edit]

Modernization of style

[edit]

Huế's Đồng Khánh Girl's High School, which opened in 1917, was widely praised for the áo dài uniform worn by its students.[17] The first modernized áo dài appeared at a Paris fashion show in 1921. In 1930, Hanoi artist Cát Tường, also known as Le Mur, designed a dress inspired by the áo ngũ thân and by Paris fashions. It reached to the floor and fit the curves of the body by using darts and a nipped-in waist.[18] When fabric became inexpensive, the rationale for multiple layers and thick flaps disappeared. Modern textile manufacture allows for wider panels, eliminating the need to sew narrow panels together. The áo dài Le Mur, or "trendy" ao dai, created a sensation when model Nguyễn Thị Hậu wore it for a feature published by the newspaper Today in January 1935.[19] The style was promoted by the artists of Tự Lực văn đoàn ("Self-Reliant Literary Group") as a national costume for the modern era.[20] The painter Lê Phô introduced several popular styles of ao dai beginning in 1934. Such Westernized garments temporarily disappeared during World War II (1939–45).

In the 1950s, Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) designers tightened the fit of the áo dài to create the version commonly seen today.[10] Trần Kim of Thiết Lập Tailors and Dũng of Dũng Tailors created a dress with raglan sleeves and a diagonal seam that runs from the collar to the underarm.[10] Madame Nhu, first lady of South Vietnam, popularized a collarless version beginning in 1958. The áo dài was most popular from 1960 to 1975.[21] A brightly colored áo dài hippy was introduced in 1968.[22] The áo dài mini, a version designed for practical use and convenience, had slits that extended above the waist and panels that reached only to the knee.[18]

Communist period

[edit]The áo dài has always been more common in the South than in the North. The communists, who gained power in the North in 1954 and in the South in 1975, had conflicted feelings about the áo dài. They praised it as a national costume and one was worn to the Paris Peace Conference (1969–73) by Viet Cong negotiator Nguyễn Thị Bình.[23] Yet Westernized versions of the dress and those associated with "decadent" Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) of the 1960s and early 1970s were condemned.[24] Economic crisis, famine, and war with Cambodia combined to make the 1980s a fashion low point.[25] The áo dài was rarely worn except at weddings and other formal occasions, with the older, looser-fitting style preferred.[24] Overseas Vietnamese, meanwhile, kept tradition alive with "Miss Ao Dai" pageants (Hoa Hậu Áo Dài), the most notable one held annually in Long Beach, California.[10]

The áo dài experienced a revival beginning in late 1980s, when state enterprise and schools began adopting the dress as a uniform again.[10] In 1989, 16,000 Vietnamese attended a Miss Ao Dai Beauty Contest held in Ho Chi Minh City.[26] When the Miss International Pageant in Tokyo gave its "Best National Costume" award to an áo dài-clad Trường Quỳnh Mai in 1995, Thời Trang Trẻ (New Fashion Magazine) claimed that Vietnam's "national soul" was "once again honored".[27] An "áo dài craze" followed that lasted for several years and led to wider use of the dress as a school uniform.[28]

Present day

[edit]

No longer deemed politically controversial, áo dài fashion design is supported by the Vietnamese government.[25] It is often called áo dài Việt Nam to link it to patriotic feelings. Designer Le Si Hoang is a celebrity in Vietnam and his shop in Ho Chi Minh City is the place to visit for those who admire the dress.[25] In Hanoi, tourists get fitted with áo dài on Luong Van Can Street.[29] The elegant city of Huế in the central region is known for its áo dài, nón lá (lit. 'traditional leaf hat'), and well-dressed women.

The áo dài is now a standard for weddings, for celebrating Tết and for other formal occasions. It is the required uniform for female teachers (mostly from high school to below) and female students in common high schools in the South; there is no requirement for color or pattern for teachers while students use plain white or with some small patterns like flowers for use as school uniforms. Companies often require their female staff to wear uniforms that include the áo dài, so flight attendants, receptionists, bank female staff, restaurant staff, and hotel workers in Vietnam may be seen wearing it.

The most popular style of áo dài fits tightly around the wearer's upper torso, emphasizing her bust and curves. Although the dress covers the entire body, it is thought to be provocative, especially when made of thin fabric. "The áo dài covers everything, but hides nothing", according to one saying.[23] The dress must be individually fitted and usually requires several weeks for a tailor to complete. An ao dai costs about $200 in the United States and about $40 in Vietnam.[30]

"Symbolically, the áo dài invokes nostalgia and timelessness associated with a gendered image of the homeland for which many Vietnamese people throughout the diaspora yearn," wrote Nhi T. Lieu, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin.[11] The difficulties of working while wearing an ao dai link the dress to frailty and innocence, she wrote.[11] Vietnamese writers who favor the use of the áo dài as a school uniform cite the inconvenience of wearing it as an advantage, a way of teaching students feminine behavior such as modesty, caution, and a refined manner.[28]

The áo dài is featured in an array of Asian-themed or related movies. In Good Morning, Vietnam (1987), Robin Williams's character is wowed by áo dài-clad women when he first arrives in Ho Chi Minh City. The 1992 films Indochine and The Lover inspired several international fashion houses to design áo dài collections,[31] including Prada's SS08 collection and a Georgio Armani collection. In the Vietnamese film The White Silk Dress (2007), an áo dài is the sole legacy that the mother of a poverty-stricken family has to pass on to her daughters.[32] The Hanoi City Complex, a 65-story building now under construction, will have an áo dài-inspired design.[33] Vietnamese designers created áo dài for the contestants in the Miss Universe beauty contest, which was held July 2008 in Nha Trang, Vietnam.[34] The most prominent annual Ao Dai Festival outside of Vietnam is held each year in San Jose, California, a city that is home to a large Vietnamese American community.[35] This event features an international array of designer áo dài under the direction of festival founder, Jenny Do.

In recent years, a shorter, more modern version of the áo dài, known as the áo dài cách tân, is often worn by the younger generation. This modern áo dài has a shorter front and back flap, hitting just below the knees.

Criticism

[edit]Áo dài is the traditional attire of Vietnam, considered a symbol of the graceful and elegant beauty of Vietnamese women.[36][better source needed][8][better source needed][37] However, besides the praises, áo dài also cannot escape criticism.[38][39]

One of the most common criticisms of áo dài is the excessive renovation.[40][41] In recent years, áo dài renovation has become very popular, with a variety of styles, materials, and colors. However, some people believe that excessive renovation has eroded the traditional beauty of áo dài.[42][43] They believe that áo dài should keep its traditional style, material, and color, to enhance the gentle and elegant beauty of Vietnamese women.[44][45]

Another criticism of áo dài is the wearing of áo dài that is offensive.[46][47][48] In recent years, there have been no shortage of cases of celebrities being criticized for wearing offensive áo dài.[49][50][51] They were accused of using áo dài to show off their bodies, causing offense to the viewer.[52][53]

In addition, áo dài is also criticized as being incompatible with modern life.[54][55] Áo dài is a traditional costume designed to be worn on formal occasions and festivals. However, in modern life, many people believe that áo dài is not suitable for everyday activities, such as going to school, going to work, going out, etc.[56][57]

Similar garments

[edit]Áo dài looks similar to the cheongsam as they both consist of a long robe with side splits on both sides of the robe with one of the main difference typically being the height of the side split.[58]

Áo dài is also similar to the shalwar kameez and the kurta of countries following Indo-Islamic culture such as India, Pakistan, etc.[59]

Gallery

[edit]-

Five Hanoi sisters wearing Áo dài, 1950s

-

Saigon old man wearing traditional Áo dài and Khăn vấn, Tết 1963

-

A female student wearing Áo dài, April 2002

-

Two woman wearing pink Áo dài, October 2006

-

A woman wearing cyan Áo dài and Nón lá, July 2008

-

The female students wearing purple Áo dài are dancing, January 2009

-

A woman wearing cyan Áo dài is performing, September 2013

-

A woman wearing violet Áo dài and Nón lá, October 2014

-

A young girl wearing white Áo dài and holding Nón lá in her right hand, June 2015

-

A woman wearing red Áo dài is sitting on a chair, December 2016

-

Two women wearing blue Áo dài, February 2017

-

A girl wearing white Áo dài is sitting, February 2020

-

A woman wearing yellow Áo dài, May 2021

See also

[edit]- Áo giao lĩnh

- Áo tứ thân

- Kurta

- Shalwar kameez

- Khăn vấn

- Nón lá

- Culture of Vietnam

- History of Vietnam

- Vietnamese clothing

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Ao dai" appears in the Oxford English Dictionary, the American Heritage Dictionary (2004), and the Random House Unabridged Dictionary (2006). Other Vietnamese words that appear include "Tet", "Vietminh", "Vietcong", and "pho" (rice noodles).[1]

- ^ A court historian described the dress in Huế as follows: "Outside court, men and women wear gowns with straight collars and short sleeves. The sleeves are large or small depending on the wearer. There are seams on both sides running down from the sleeve, so the gown is not open anywhere. Men may wear a round collar and a short sleeve for more convenience." ("Thường phục thì đàn ông, đàn bà dùng áo cổ đứng ngắn tay, cửa ống tay rộng hoặc hẹp tùy tiện. Áo thì hai bên nách trở xuống phải khâu kín liền, không được xẻ mở. Duy đàn ông không muốn mặc áo cổ tròn ống tay hẹp cho tiện khi làm việc thì được phép…") (from Đại Nam Thực Lục [Records of Đại Nam])

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of ao dai | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com.

- ^ "Ao dai definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com.

- ^ "Definition of ao dai in English". September 16, 2013. Archived from the original on September 16, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

Áo is derived from a Middle Chinese word (襖) meaning "padded coat". "襖". Han Dian. Retrieved May 20, 2023. - ^ Phan Van Giuong, Tuttle Compact Vietnamese Dictionary: Vietnamese–English English–Vietnamese (2008), p. 76. "dài adj. long, lengthy."

- ^ Trần Hậu Yên Thế (December 26, 2023). "Họa sĩ Cát Tường và trang phục áo dài Lemur". Tạp chí Người Hà Nội Online.

- ^ "Câu chuyện kỳ thú về mối lương duyên của họa sĩ Cát Tường - người sáng tạo ra áo dài Việt Nam hôm nay". Chúng ta. July 20, 2021.

- ^ "Chuyện về danh họa Nguyễn Cát Tường, người thiết kế nên chiếc áo dài đầu tiên của Việt Nam". Sàigòneer. February 9, 2022.

- ^ a b "Bài 1: Áo dài - Niềm tự hào văn hóa Việt". dangcongsan.vn. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ a b "Sự khác biệt về cách may giữa Áo Cổ Đứng Xưa và Áo Dài Tân Thời". June 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ellis, Claire (1996). "Ao Dai: The National Costume". Things Asian. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ a b c Lieu (2000), p. 127–151.

- ^ Niessen, Leshkowich & Jones (2003), p. 89.

- ^ a b Vu, Thuy (2014). "Đi tìm ngàn năm áo mũ". Tuoi Tre. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ T.Van (2013). "Ancient costumes of Vietnamese people". Vietnamnet. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Leshkowich 2005, p. 61.

- ^ "TRANG PHỤC (THƯỜNG PHỤC) Ở ĐÀNG TRONG THỜI VÕ VƯƠNG NGUYỄN PHÚC KHOÁT – NHỮNG NÉT ĐẶC TRƯNG". Bình Nguyên - Võ Vinh Quang (in Vietnamese). October 8, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Kauffner, Peter (September–October 2010). "Áo dài" (PDF). Asia Insights Destination Asia. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2023 – via Visions of Indochina.com.

- ^ a b Niessen, Leshkowich & Jones (2003), p. 91.

- ^ "A Fashion Revolution". Ninh Thuận P&T. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.. For a picture of the áo dài Le Mur, see Ao Dai — The Soul of Vietnam[permanent dead link].

- ^ "Vietnamese Ao dai history". Aodai4u. Archived from the original on August 19, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Elmore, Mick (September 17, 1997). "Ao Dai Enjoys A Renaissance Among Women : In Vietnam, A Return to Femininity". International Herald Tribune.

- ^ Bich Vy-Gau Gi, Ao Dai — The Soul of Vietnam[permanent dead link]. Retrieved on July 2, 2008.

- ^ a b "Vietnamese AoDai". Overlandclub. Archived from the original on March 19, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ a b Niessen, Leshkowich & Jones (2003), p. 92.

- ^ a b c Valverde, Caroline Kieu (2006). "The History and Revival of the Vietnamese Ao Dai". NHA magazine. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Vu, Lan (2002). "Ao Dai Viet Nam". Viettouch. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ^ Niessen, Leshkowich & Jones (2003), p. 79.

- ^ a b Niessen, Leshkowich & Jones (2003), p. 97.

- ^ "Traditional ao dai grace foreign bodies". VNS. December 20, 2004. Archived from the original on December 24, 2004. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "Ao Dai Couture". Nha magazine. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ "Ao Dai – Vietnamese Plus Size Fashion Statement". Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ "Vietnam send Ao Lua Ha Dong to Pusan Film Festival". VietNamNet Bridge. 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ^ Tuấn Cường. ""Nóc nhà" Hà Nội sẽ cao 65 tầng". Tuoi Tre (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on March 28, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ "Miss Universe contestants try on ao dai". Vietnam.net Bridge. 2008. Archived from the original on July 1, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ "| A Celebration of Vietnamese Art and Culture". Ao Dai Festival.

- ^ "Áo dài: Nét đẹp văn hóa truyền thống của người phụ nữ Việt Nam". Báo mega.vietnamplus.vn (in Vietnamese). October 26, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Hùng, Việt (2010). Áo dài Việt Nam: truyền thống, đời thường, cách điệu (in Vietnamese). Mỹ Thụât.

- ^ PHÓNG, BÁO SÀI GÒN GIẢI (October 18, 2016). "Áo dài, đừng để cách tân trở thành "thảm họa"". BÁO SÀI GÒN GIẢI PHÓNG (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ MEDIATECH. "Áo dài cách tân: Sáng tạo nhưng phải có chừng mực". nbtv.vn (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Những mẫu áo dài cách tân quá đà của sao Việt khiến dư luận giận dữ". laodong.vn (in Vietnamese). August 13, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ ONLINE, TUOI TRE (April 23, 2023). "'Cách tân kiểu gì cũng được nhưng khi đó đừng gọi là áo dài'". TUOI TRE ONLINE (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Giữ gìn nét đẹp truyền thống của áo dài". Báo Nhân Dân điện tử (in Vietnamese). February 11, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Áo dài cách tân - hòa mình với cuộc sống hiện đại". Báo Pháp luật Việt Nam điện tử (in Vietnamese). March 7, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Tôn vinh vẻ đẹp của áo dài Việt Nam tại Hà Nam". Báo Hà Nam điện tử. October 24, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Vietnam+ (VietnamPlus) (February 13, 2021). "Áo dài - Di sản văn hóa Việt, niềm tự hào của người Việt Nam". Vietnam+ (VietnamPlus) (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ thanhnien.vn. "Hoa hậu Thái Lan mặc áo dài lộ nội y ren phản cảm". thanhnien.vn (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ congly.vn (March 24, 2023). "Áo dài xuyên thấu: Cách tân, hợp thời, hay phản cảm?". congly.vn (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ ONLINE, TUOI TRE (June 8, 2023). "Diễn áo dài, áo yếm phản cảm: Đề xuất phạt 85 triệu đồng". TUOI TRE ONLINE (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ NLD.COM.VN. "Siêu mẫu Hà Anh lại bị chỉ trích sau sự cố mặc áo dài phản cảm". Báo Người Lao Động Online (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Hoa hậu Ngọc Châu mặc áo dài xuyên thấu, bị chê dung tục". Báo điện tử Tiền Phong (in Vietnamese). March 25, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ NLD.COM.VN. "Hà Anh mặc áo dài phản cảm, BTC Hoa hậu bị phạt 70 triệu đồng". Báo Người Lao Động Online (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ VCCorp.vn (March 15, 2016). "Áo dài vốn đã quyến rũ, đừng cố cách điệu để khoe thân". afamily.vn (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Angela Phương Trinh và loạt sao từng bị chỉ trích dùng áo yếm khoe thân". laodong.vn (in Vietnamese). June 4, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ ONLINE, TUOI TRE (September 13, 2020). "Truyền thống bền vững nhưng không biết cách bảo tồn nó sẽ rơi về phía mong manh". TUOI TRE ONLINE (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ Trí, Dân (November 14, 2013). "Áo dài- từ "biểu tượng văn hóa" đến… "thảm họa văn hóa" (II)". Báo điện tử Dân Trí (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ danviet.vn (February 25, 2016). "Mặc áo dài hàng ngày: Nên hay không?". danviet.vn (in Vietnamese). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Áo dài Việt trong đời sống hàng ngày". Báo Pháp luật Việt Nam điện tử (in Vietnamese). March 5, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ^ "Vietnam Traditional Clothes: Ao Dai – VietnamOnline". www.vietnamonline.com. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Bach, Trinh (2020). "Origin of Vietnamese Ao Dai". Retrieved July 23, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Leshkowich, Ann Marie (2005). Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion.

- Li, Tana (1998). Nguyễn Cochichina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Southeast Asia Program Publications. ISBN 9780877277224.

- Lieu, Nhi T. (2000). "Remembering 'the Nation' through pageantry: femininity and the politics of Vietnamese womanhood in the 'Hoa Hau Ao Dai' contest". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 21 (1–2). University of Nebraska Press: 127–151. doi:10.2307/3347038. JSTOR 3347038.

- Niessen, S. A.; Leshkowich, Ann Marie; Jones, Carla, eds. (2003). Re-Orienting Fashion: The Globalization of Asian Dress. Berg. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-85973-539-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Trần Quang Đức (2013). Ngàn Năm Áo Mũ. Lịch sử trang phục Việt Nam 1009–1945 [A Thousand Years of Caps and Robes. A history of Vietnamese costumes 1009–1945]. Nhã Nam. OCLC 862888254.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Áo dài at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Áo dài at Wikimedia Commons

- A modern gallery of Áo dài photographs

- History of the Vietnamese Long Dress

- The Evolution of the Ao Dai Through Many Eras, Gia Long Alumni Association of Seattle, 2000

- Vietnam: Mini-Skirts & Ao-Dais. A video that shows what the women of Saigon wore in 1968

- Ao Dai, the Traditional Dress in Vietnam