Amphetamine: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 169.199.121.4 to last revision by Islam123098 (HG) |

Dylancatlow (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| ATC_suffix=BA01 |

| ATC_suffix=BA01 |

||

| ATC_supplemental= |

| ATC_supplemental= |

||

| PubChem= |

| PubChem==C1)N |

||

| DrugBank=APRD00480 |

|||

| synonyms = (±)-alpha-methylbenzeneethanamine, alpha-methylphenethylamine, beta-phenyl-isopropylamine |

|||

| smiles = CC(CC1=CC=CC=C1)N |

|||

| C=9 | H=13 | N=1 | |

| C=9 | H=13 | N=1 | |

||

| molecular_weight = 135.2084 |

| molecular_weight = 135.2084 |

||

| Line 20: | Line 17: | ||

| melting_high = 281 |

| melting_high = 281 |

||

| protein_bound = 15–40% |

| protein_bound = 15–40% |

||

| metabolism = [[Hepatic]] ([[CYP2D6]]< |

| metabolism = [[Hepatic]] ([[CYP2D6]]<rejdedefefef>{{cite journal |author=Miranda-G E, Sordo M, Salazar AM, ''et al'' |title=Determination of amphetamine, methamphetamine, and hydroxyamphetamine derivatives in urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and its relation to CYP2D6 phenotype of drug users |journal=J Anal Toxicol |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=31–6 |year=2007 |pmid=17389081 |url=http://openurl.ingenta.com/content/nlm?genre=article&issn=0146-4760&volume=31&issue=1&spage=31&aulast=Miranda-G}}</ref>) |

||

| elimination_half-life= 12h average for d-isomer, 13h for l-isomer |

| elimination_half-life= 12h average for d-isomer, 13h for l-isomer |

||

| excretion = [[Renal]]; significant portion unaltered |

| excretion = [[Renal]]; significant portion unaltered |

||

| Line 130: | Line 127: | ||

==Major neurobiological mechanisms== |

==Major neurobiological mechanisms== |

||

===Primary sites of action=== |

===Primary sites of action=== |

||

Amphetamine exerts its behavioral effects by modulating the behavior of several key neurotransmitters in the brain, including [[dopamine]], [[serotonin]], and [[norepinephrine]]. However, the activity of amphetamine throughout the brain appears to be specific;<ref name="JonesKornblum">{{cite journal |author=Jones S, Kornblum JL, Kauer JA |title=Amphetamine blocks long-term |

Amphetamine exerts its behavioral effects by modulating the behavior of several key neurotransmitters in the brain, including [[dopamine]], [[serotonin]], and [[norepinephrine]]. However, the activity of amphetamine throughout the brain appears to be specific;<ref name="JonesKornblum">{{cite journal |author=Jones S, Kornblum JL, Kauer JA |title=Amphetamine blocks long-term syfefeffenaptic depression in thefef ventral tegmental area |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=20 |issue=15 |pages=5575–80 |year=2000 |month=August |pmid=10908593 |doi= |url=http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10908593}}</ref> certain receptors that respond to amphetamine in sofefefefeffeme regions of the brain tend not to do so in other regions. For instance, [[dopamine]] [[Dopamine receptor|D2 receptors]] in the [[hippocampus]], a region of the brain associated with forming new memories, appear to be unaffected by the presence of amphetamine.<ref name="JonesKornblum" /> |

||

efef |

|||

The major neural systems affected by amphetamine are largely implicated in the brain’s reward circuitry. Moreover, neurotransmitters |

The major neural systems affected by amphetamine are largely implicated in the brain’s reward circuitry. Moreover, neurotransmitters ifefefenvolvefeffd in various reward pathways of the brain appear to be the primary targets of amphetamine.<ref name="pmid17437">{{cite journal |author=Moore KE |title=The actions of amphetamine on neurotransmitters: a brief review |journal=Biol. Psychiatry |volume=12 |issue=3 |pages=451–62 |year=1977 |month=June |pmid=17437 |doi= |url=}}</ref> One such neurotransmitter is [[dopamine]], a chemical messenger heavily active in the [[Mesolimbic pathway|mesolimbic]] and [[Mesocortical pathway|mesocortical]] reward pathways. Not surprisingly, the anatomical components of these pathways—including the [[striatum]], the [[nucleus accumbens]], and the [[ventral striatum]]—have been found to be primary sites of amphetamine action.<ref name="DelArco">{{cite journal |author=Del Arco A, González-Mora JL, Armas VR, Mora F |title=Amphetamine increases the extracellular concentration of glutamate in striatum of the awake rat: involvement of high affinity transporter mechanisms |journal=Neuropharmacology |volume=38 |issue=7 |pages=943–54 |year=1999 |month=July |pmid=10428413 |doi=10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00043-X |url=}}</ref><ref name="Drevets">{{cite journal |author=Drevets WC, Gautier C, Price JC, ''et al'' |title=Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in human ventral striatum correlates with euphoria |journal=Biol. Psychiatry |volume=49 |issue=2 |pages=81–96 |year=2001 |month=January |pmid=11164755 |doi=10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01038-6 |url=}}</ref> |

||

The fact that amphetamines influence neurotransmitter activity specifically in regions implicated in reward provides insight into the behavioral consequences of the drug, such as the stereotyped onset of [[euphoria]].<ref name="Drevets" /> A better understanding of the specific mechanisms by which amphetamines operate may increase our ability to treat amphetamine [[addiction]], as the brain’s reward circuitry has been widely implicated in addictions of many types.<ref>Wise, RA. “Brain reward circuitry and addiction.” Program and abstracts of the American Society of Addiction Medicine 2003 The State of the Art in Addiction Medicine; October 30-November 1, 2003; Washington, DC. Session </ref> |

The fact that amphetamines influence neurotransmitter activity specifically in regions implicated in reward provides insight into the behavioral consequences of the drug, such as the stereotyped onset of [[euphoria]].<ref name="Drevets" /> A better understanding of the specific mechanisms by which amphetamines operate may increase our ability to treat amphetamine [[addiction]], as the brain’s reward circuitry has been widely implicated in addictions of many types.<ref>Wise, RA. “Brain reward circuitry and addiction.” Program and abstracts of the American Society of Addiction Medicine 2003 The State of the Art in Addiction Medicine; October 30-November 1, 2003; Washington, DC. Session </ref> |

||

Revision as of 01:31, 21 May 2009

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous, vaporization, insufflation, suppository, sublingual |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral 20-25%;[2] nasal 75%; rectal 95–99%; intravenous 100% |

| Protein binding | 15–40% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2D6<rejdedefefef>Miranda-G E, Sordo M, Salazar AM; et al. (2007). "Determination of amphetamine, methamphetamine, and hydroxyamphetamine derivatives in urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and its relation to CYP2D6 phenotype of drug users". J Anal Toxicol. 31 (1): 31–6. PMID 17389081. {{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in: |author= (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)</ref>) |

| Elimination half-life | 12h average for d-isomer, 13h for l-isomer |

| Excretion | Renal; significant portion unaltered |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.543 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H13N |

| Molar mass | 135.2084 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 285 to 281 °C (545 to 538 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 50–100 mg/mL (16C°) mg/mL (20 °C) |

Amphetamine is a psychostimulant drug that is known to produce increased wakefulness and focus in association with decreased fatigue and appetite. Amphetamine is related to drugs such as methamphetamine, dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine, which are a group of potent drugs that act by increasing levels of norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine in the brain, inducing euphoria.[3] The group includes prescription CNS drugs commonly used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults and children. It is also used to treat symptoms of traumatic brain injury and the daytime drowsiness symptoms of narcolepsy, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome. Initially, amphetamine was more popularly used to diminish the appetite and to control weight. Brand names of the drugs that contain amphetamine include Adderall, Vyvanse, and Dexedrine. The drug is also used illegally as a recreational drug and as a performance enhancer. The name amphetamine is derived from its chemical name: alpha-methylphenethylamine. The name is also used to refer to the class of compounds derived from amphetamine, often referred to as the substituted amphetamines.[citation needed]

Recreational users of amphetamine have coined numerous nicknames for amphetamine, some of the more common street names for amphetamine include speed, crank, and whizz. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports the typical retail price of amphetamine in Europe varied between 10€ and 15€ a gram in half of the reporting countries.[4]

History

Amphetamine was first synthesized in 1887 by the Romanian Lazăr Edeleanu in Berlin, Germany.[5] He named the compound phenylisopropylamine. It was one of a series of compounds related to the plant derivative ephedrine, which had been isolated from Ma-Huang that same year by Nagayoshi Nagai.[6] No pharmacological use was found for amphetamine until 1927, when pioneer psychopharmacologist Gordon Alles resynthesized and tested it on himself, in search of an artificial replacement for ephedrine. From 1933 or 1934 Smith, Kline and French began selling the volatile base form of the drug as an inhaler under the trade name Benzedrine, useful as a decongestant but readily usable for non-medical purposes.[7] One of the first attempts at using amphetamines as a scientific study was done by M. H. Nathanson, a Los Angeles physician, in 1935. He studied the subjective effects of amphetamine in 55 hospital workers who were each given 20 mg of Benzedrine. The two most commonly reported drug effects were "a sense of well being and a feeling of exhilaration" and "lessened fatigue in reaction to work".[8] During World War II amphetamine was extensively used to combat fatigue and increase alertness in soldiers. After decades of reported abuse, the FDA banned Benzedrine inhalers, and limited amphetamines to prescription use in 1965, but non-medical use remained common. Amphetamine became a schedule II drug under the Controlled Substances Act in 1971.

The related compound methamphetamine was first synthesized from ephedrine in Japan in 1918 by chemist Akira Ogata, via reduction of ephedrine using red phosphorus and iodine. The German military was notorious for their use of methamphetamine in World War II[citation needed]. Adolf Hitler received daily shots of a medicine his doctor called "vitamultine", which contained various essential vitamins in addition to methamphetamine[citation needed]. The pharmaceutical Pervitin was a tablet of 3 mg methamphetamine which was available in Germany from 1938 and widely used in the Wehrmacht, but by mid-1941 it became a controlled substance, partly because of the amount of time needed for a soldier to rest and recover after use and partly because of abuse. For the rest of the war, military doctors continued to issue the drug, but less frequently and with increasing discrimination as the war progressed onwards towards Nazi Germany's and the Axis' eventual defeat in 1945.[9]

In 1997 and 1998,[10][11] researchers at Texas A&M University claimed to have found amphetamine and methamphetamine in the foliage of two Acacia species native to Texas, A. berlandieri and A. rigidula. Previously, both of these compounds had been thought to be human inventions. These findings have never been duplicated, and the analyses are believed by many biochemists to be the result of experimental error, and as such the validity of the report has come into question. Alexander Shulgin, one of the most experienced biochemical investigators and the discoverer of many new psychotropic substances, has tried to contact and verify the Texas A&M findings. The authors of the paper have not responded; natural amphetamine remains most likely a false discovery.[12]

Amphetamines were still in use in the US Air Force as of 2003. They are believed to have played a role in the deaths of four Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan involved in a friendly fire incident.[13]

Indications

Indicated for:

|

Contraindications:

|

Adverse effects:

|

| Other information: |

Along with methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, etc.), amphetamine is one of the standard treatments for ADHD. Beneficial effects for ADHD can include improved impulse control, improved concentration, decreased sensory overstimulation, decreased irritability and decreased anxiety. These effects on productivity can be dramatic in both young children and adults. The ADHD medication Adderall is composed of four different amphetamine salts, and Adderall XR is a timed-release formulation of these same salt forms.

When used within the recommended doses, side-effects like loss of appetite tend to decrease over time. However, amphetamines last longer in the body than methylphenidate and tend to have stronger side-effects on appetite and sleep.

Amphetamines are also a standard treatment for narcolepsy, as well as other sleeping disorders. If used within therapeutic limits, amphetamines are generally effective over long periods of time without producing addiction or physical dependence.

Amphetamines are sometimes used to augment anti-depressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression.

Medical use for weight loss is still approved in some countries, but is regarded as obsolete and dangerous in others.

Contraindications

Amphetamine elevates cardiac output and blood pressure making it dangerous for use by patients with a history of heart disease or hypertension. Amphetamine can cause a life-threatening complication in patients taking MAOI antidepressants. Amphetamine is not suitable for patients with a history of glaucoma.[citation needed] Amphetamine has been shown to pass through into breast milk. Because of this, mothers taking amphetamine are advised to avoid breastfeeding during their course of treatment.[14] Many women who use amphetamine find that their periods become irregular or even stop. Both amphetamine and the pill increase blood pressure which in the long term can affect the heart, blood vessels and liver. Further, amphetamine can inhibit the effects of the contraceptive pill which may cause it to work less effectively. The weight loss sometimes associated with amphetamine use may also cause the contraceptive cap or diaphragm to be less effective as it will not fit as well. [15]

Major neurobiological mechanisms

Primary sites of action

Amphetamine exerts its behavioral effects by modulating the behavior of several key neurotransmitters in the brain, including dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. However, the activity of amphetamine throughout the brain appears to be specific;[16] certain receptors that respond to amphetamine in sofefefefeffeme regions of the brain tend not to do so in other regions. For instance, dopamine D2 receptors in the hippocampus, a region of the brain associated with forming new memories, appear to be unaffected by the presence of amphetamine.[16] efef The major neural systems affected by amphetamine are largely implicated in the brain’s reward circuitry. Moreover, neurotransmitters ifefefenvolvefeffd in various reward pathways of the brain appear to be the primary targets of amphetamine.[17] One such neurotransmitter is dopamine, a chemical messenger heavily active in the mesolimbic and mesocortical reward pathways. Not surprisingly, the anatomical components of these pathways—including the striatum, the nucleus accumbens, and the ventral striatum—have been found to be primary sites of amphetamine action.[18][19]

The fact that amphetamines influence neurotransmitter activity specifically in regions implicated in reward provides insight into the behavioral consequences of the drug, such as the stereotyped onset of euphoria.[19] A better understanding of the specific mechanisms by which amphetamines operate may increase our ability to treat amphetamine addiction, as the brain’s reward circuitry has been widely implicated in addictions of many types.[20]

Endogenous amphetamines

Amphetamine has been found to have several endogenous analogues; that is, molecules of a similar structure found naturally in the brain.[21] l-Phenylalanine and β-Phenethylamine are two examples, which are formed in the peripheral nervous system as well as in the brain itself. These molecules are thought to modulate levels of excitement and alertness, among other related affective states.

Dopamine

Perhaps the most widely studied neurotransmitter with regard to amphetamine action is dopamine, the “reward neurotransmitter” that is highly active in numerous reward pathways of the brain. Various studies have shown that in select regions, amphetamine increases the concentrations of dopamine in the synaptic cleft, thereby heightening the response of the post-synaptic neuron.[22] This specific action hints at the hedonic response to the drug as well as to the drug’s addictive quality.

The specific mechanisms by which amphetamines affect dopamine concentrations have been studied extensively. Currently, two major hypotheses have been proposed, which are not mutually exclusive. One theory emphasizes amphetamine’s actions on the vesicular level, increasing concentrations of dopamine in the cytosol of the pre-synaptic neuron.[21][23] The other focuses on the role of the dopamine transporter DAT, and proposes that amphetamine may interact with DAT to induce reverse transport of dopamine from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic cleft.[17][24][25][26]

The former hypothesis is backed by data demonstrating that injections of amphetamines result in rapid increases of cytosolic dopamine concentrations.[26] Amphetamine is believed to interact with dopamine-containing vesicles in the axon terminal, called VMATs, in a way that releases dopamine molecules into the cytosol. The redistributed dopamine is then believed to interact with DAT to promote reverse transport.[21] Calcium may be a key molecule involved in the interactions between amphetamine and VMATs.[23]

The latter hypothesis postulates a direct interaction between amphetamine and the DAT transporter. The activity of DAT is believed to depend on specific phosphorylating kinases, such as PKC-β.[26] Upon phosphorylation, DAT undergoes a conformational change that results in the transportation of DAT-bound dopamine from the extracellular to the intracellular environment.[25] In the presence of amphetamine, however, DAT has been observed to function in reverse, spitting dopamine out of the presynaptic neuron and into the synaptic cleft.[24] Thus, beyond inhibiting reuptake of dopamine, amphetamine also stimulates the release of dopamine molecules into the synapse.[17]

In support of the above hypothesis, it has been found that PKC-β inhibitors eliminate the effects of amphetamine on extracellular dopamine concentrations in the striatum of rats.[26] This data suggests that the PKC-β kinase may represent a key point of interaction between amphetamine and the DAT transporter.

Serotonin

Amphetamine has been found to exert similar effects on serotonin as on dopamine.[27] Like DAT, the serotonin transporter SERT can be induced to operate in reverse upon stimulation by amphetamine.[28] This mechanism is thought to rely on the actions of calcium molecules, as well as on the proximity of certain transporter proteins.[28]

The interaction between amphetamine and serotonin is only apparent in particular regions of the brain, such as the mesocorticolimbic projection. Recent studies additionally postulate that amphetamine may indirectly alter the behavior of glutamatergic pathways extending from the ventral tegmental area to the prefrontal cortex.[27] Glutamatergic pathways are strongly correlated with increased excitability at the level of the synapse. Increased extracellular concentrations of serotonin may thus modulate the excitatory activity of glutamatergic neurons.[27]

The proposed ability of amphetamine to increase excitability of glutamatergic pathways may be of significance when considering serotonin-mediated addiction.[27] An additional behavioral consequence may be the stereotyped locomotor stimulation that occurs in response to amphetamine exposure.[22]

Other relevant neurotransmitters

Several other neurotransmitters have been linked to amphetamine activity. For instance, extracellular levels of glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, have been shown to increase upon exposure to amphetamine. Consistent with other findings, this effect was found in the areas of the brain implicated in reward; namely, the nucleus accumbens, striatum, and prefrontal cortex.[18]

Additionally, several studies demonstrate increased levels of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter related to adrenaline, in response to amphetamine. This is believed to occur via reuptake blockage as well as via interactions with the norepinephrine neuronal transport carrier.[29]

Pharmacology

Chemical properties

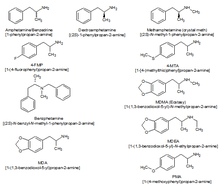

Amphetamine is a chiral compound. The racemic mixture can be divided into its optical isomers: levo- and dextro-amphetamine. Amphetamine is the parent compound of its own structural class, comprising a broad range of psychoactive derivatives, from empathogens, MDA (3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine) and MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine) known as ecstasy, to the N-methylated form, methamphetamine known as 'meth', and to decongestants such as ephedrine (EPH) . Amphetamine is a homologue of phenethylamine.

At first, the medical drug came as the salt racemic-amphetamine sulfate (racemic-amphetamine contains both isomers in equal amounts). Attention disorders are often treated using Adderall or a generic equivalent, a formulation of mixed amphetamine and dextroamphetamine salts that contain

- 1/4 dextroamphetamine saccharate

- 1/4 dextroamphetamine sulfate

- 1/4 (racemic dextro/laevo-amphetamine) aspartate monohydrate

- 1/4 (racemic dextro/laevo-amphetamine) sulfate

Pharmacodynamics

Amphetamine has been shown to both diffuse through the cell membrane and travel via the dopamine transporter (DAT) to increase concentrations of dopamine in the neuronal terminal.

Amphetamine, both as d-amphetamine (dextroamphetamine) and l-amphetamine (or a racemic mixture of the two isomers), is believed to exert its effects by binding to the monoamine transporters and increasing extracellular levels of the biogenic amines dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and serotonin. It is hypothesized that d-amphetamine acts primarily on the dopaminergic systems, while l-amphetamine is comparatively norepinephrinergic (noradrenergic). The primary reinforcing and behavioral-stimulant effects of amphetamine, however, are linked to enhanced dopaminergic activity, primarily in the mesolimbic dopamine system.

Amphetamine and other amphetamine-type stimulants principally act to release dopamine into the synaptic cleft. Amphetamine, unlike similar dopamine acting stimulant cocaine, does not act as a ligand but does slow reuptake by a secondary acting mechanism through the phosphorylation of dopamine transporters.[30] The primary action is through the increased amphetamine concentration which releases endogenous stores of dopamine from vesicular monoamine transporters (VMATs), thereby increasing intra-neuronal concentrations of transmitter. This increase in concentration effectively reverses transport of dopamine via the dopamine transporter (DAT) into the synapse.[31] In addition, amphetamine binds reversibly to the DATs and blocks the transporter's ability to clear DA from the synaptic space. Amphetamine also acts in this way with norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and to a lesser extent serotonin.

In addition, amphetamine binds to a group of receptors called TrAce Amine Receptors (TAAR).[32] TAAR are a newly discovered receptor system which seems to be affected by a range of amphetamine-like substances called trace amines.

Effects

Physical effects

Physical effects of amphetamine can include reduced appetite, increased/distorted sensations, hyperactivity, dilated pupils, flushing, restlessness, dry mouth, erectile dysfunction, headache, tachycardia, increased breathing rate, increased blood pressure, fever, sweating, diarrhea, constipation, blurred vision, impaired speech, dizziness, uncontrollable movements or shaking, insomnia, numbness, palpitations, and arrhythmia. In high doses or chronic use convulsions, dry or itchy skin, acne, pallor can occur.[33][34][35][36]

Occasionally amphetamine use in males can cause an odd and sometimes startling effect to occur in which the penis when flaccid appears to have shrunk. The reason this occurs is because amphetamine is a potent vasoconstrictor or an agent that constricts blood vessels. The rigidness of the erection and the size of the penis are in part by affected by the amount of blood flow to the penis. When amphetamine constricts the blood vessels enough it reduces blood flow to the penis and then can produce a penis that is slightly smaller and this effect is often coupled along with impotence and erectile dysfunction. Upon erection the penis returns to normal size.[37]

Young adults who abuse amphetamines may be at greater risk of suffering a heart attack. In a study published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence,[38] researchers examined data from more than 3 million people between 18 and 44 years old hospitalized from 2000 through 2003 in Texas. After controlling for cocaine abuse, alcohol abuse, tobacco use, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, lipid disorders, obesity, congenital defects, and coagulation defects, they found a relationship between a diagnosis of amphetamine abuse and heart attack.[39]

Psychological effects

Psychological effects of amphetamine can include anxiety and/or general nervousness (by increased norepinephrine),[40] euphoria, metacognition, creative or philosophical thinking, increased confidence, perception of increased energy, increased sense of well being, increase of goal-orientated thoughts or organized behavior, repetitive behavior, increased concentration/mental sharpness, increased alertness, feeling of power or superiority, Increased aggression, emotional lability, excitability, talkativeness and occasionally amphetamine psychosis, typically in a high and/or chronic doses.[33] Effects are similar to other phenylethylamine stimulants and cocaine.[citation needed]

Withdrawal effects

Withdrawal from chronic recreational use of amphetamines can include anxiety, depression, agitation, fatigue, excessive sleeping, increased appetite, psychosis and suicidal thoughts.[41]

Overdose

An amphetamine overdose can lead to a number of different symptoms. Some include psychosis, chest pain, and hypertension.

Psychosis

Amphetamine psychosis usually occurs at large doses only, but it has been known to occur in children taking therapeutic doses for the treatment of ADHD.

Dependence and addiction

Tolerance is developed rapidly in amphetamine abuse, therefore increasing the amount of the drug that is needed to satisfy the addiction.[42] Repeated amphetamine use can produce "reverse tolerance", or sensitization to some psychological effects. Amphetamine does not have the potential to cause physical dependence, though withdrawal can still be hard for a user.[43][44][45][46][47][48] Many users will repeat the amphetamine cycle by taking more of the drug during the withdrawal. This leads to a very dangerous cycle and may involve the use of other drugs to get over the withdrawal process. Users will commonly stay up for 2 or 3 days to avoid the withdrawals then dose themselves with benzodiazepines, barbiturate, and in some cases heroin, to help them stay calm while they recuperate or simply to extend the positive effects of the drug. Chronic users of amphetamines sometimes snort or use drug injection to experience the full effects of the drug in a faster and more intense way, with the added risks of infection, vein damage, and higher risk of overdose with drug injection.

Performance-enhancing use

Amphetamine is used by some college and high-school students as a study and test-taking aid.[49] Amphetamine works by increasing energy levels, concentration, and motivation, thus allowing students to study for an extended period of time. This drug is often acquired through ADHD prescriptions to students and peers, rather than illicitly produced drugs.[50]

Amphetamine has been, and is still, used by militaries around the world. British troops used 72 million amphetamine tablets in the second world war[51] and the RAF used so many that "Methedrine won the Battle of Britain" according to one report.[52] American bomber pilots use amphetamine ("go pills") to stay awake during long missions. The Tarnak Farm incident, in which an American F-16 pilot killed several friendly Canadian soldiers on the ground, was blamed by the pilot on his use of amphetamine. A nonjudicial hearing rejected the pilot's claim.

Amphetamine is also used by some professional,[53] collegiate[54] and high school[54] athletes for its strong stimulant effect. Energy levels are perceived to be dramatically increased and sustained, which is believed to allow for more vigorous and longer play. However, at least one study has found that this effect is not measurable.[55] The use of amphetamine during strenuous physical activity can be extremely dangerous, especially when combined with alcohol, and athletes have died as a result, for example, British cyclist Tom Simpson.

Amphetamine use has historically been especially common among Major League Baseball players and is usually known by the slang term "greenies".[56] In 2006, the MLB banned the use of amphetamine. The ban is enforced through periodic drug-testing. If a player tests positive for amphetamine, the consequences are significant. However, the MLB has received some criticism because the consequences for amphetamine use are dramatically less severe than for anabolic steroid use, with the first offense bringing only a warning and further testing.[57][58][59]

Amphetamine was formerly in widespread use by truck drivers[60] to combat symptoms of somnolence and to increase their concentration juice on driving, especially in the decades prior to the signing by then-president Ronald Reagan of Executive Order 12564, which initiated mandatory random drug testing of all truck drivers and employees of other DOT-regulated industries. Although implementation of the order on the trucking industry was kept to a gradual rate in consideration of its projected effects on the national economy, in the decades following the order, amphetamine and other drug abuse by truck drivers has since dropped drastically. (See also Truck driver - Implementation of drug detection).

Cultural impact of amphetamine

The social and cultural impact of amphetamine has been, and continues to be, quite extensive.

From the 1960s onward, amphetamine has been popular with many youth subcultures in Britain (and other parts of the world) as a recreational drug. It has been commonly used by mods, skinheads, punks, goths, gangstas, and casuals in all night soul and ska dances, punk concerts, basement shows and fighting on the terraces by casuals.

The hippie counterculture was very critical of amphetamines due to the behaviors they cause; beat writer Allen Ginsberg wrote that users ran the risk of becoming a "Frankenstein speed freak"[61] . The mods, being working class, were often opposed to the slower, more contemplative, meditative ideals and lifestyle of the hippies. Amphetamines therefore suited their high energy and aggressive aesthetics and lifestyle, whether it was dancing to soul music at all night parties, or fighting rockers.[citation needed]

Gay HIV Issues

Studies have found higher incidence of unprotected receptive anal sex to multiple partners especially in gay bath-houses, steam-rooms, fetish clubs and nightclubs, contributing to a marked increase in AIDS infections[62]. Research by a team at the City University London found 20% of all gay young men surveyed were using methamphetamine, in clubs and in gay gyms[63]. Ted Haggard was one of many gay men who indulged in amphetamines and gay sex.[64] Shared syringes used intravenous direct injection of amphetamines are also a major contributor to HIV spread[65][66]. A study from the Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Center which offers free HIV testing, nearly one-third of positive tests in gay men were associated with amphetamine use[67]. Dr. Ron Stall (coined the term “syndemic” to specifically describe these overlapping, mutually reinforcing gay community epidemics of unsafe sex, HIV and depression.[68]

A 1992 San Francisco study of 648 seronegative gay and bisexual men found that while 33 percent of the total sample reported using speed over the course of a year, 48 percent of the 22 men who became HIV-infected during the study period used speed[citation needed] The drug was especially popular with younger gay and bisexual men. When compared with non-users, speed users reported more unsafe receptive anal intercourse, more condom breakage, and more unprotected sex with seropositive partners.[69]

The syringe exchange program in the US, UK, and many other nations was due to the unsettling findings of such studies of HIV contraction among young gay males sharing syringes for injecting amphetamines, and to a lesser extent heroin[70].[71]

In literature

The writers of the Beat Generation used amphetamine extensively, mainly under the Benzedrine brand name. Jack Kerouac was a particularly avid user of amphetamine, which was said to provide him with the stamina needed to work on his novels for extended periods of time.[72]

Scottish author Irvine Welsh often portrays drug use in his novels, though in one of his journalism works he comments on how drugs (including amphetamine) have become part of consumerism and how his novels Trainspotting and Porno reflect the changes in drug use and culture during the years that elapse between the two texts.[73]

Amphetamines are frequently mentioned in the work of American journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Speed appears not only amongst the astoundingly diverse and voluminous inventory of drugs Thompson consumed for what could broadly be defined as recreational purposes, but also receives frequent, explicit mention as an essential component of his writing toolkit[74], such as in his "Author's Note" in Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72[75]:

"One afternoon about three days ago [the publishers] showed up at my door with no warning, and loaded about forty pounds of supplies into the room: two cases of Mexican beer, four quarts of gin, a dozen grapefruits, and enough speed to alter the outcome of six Super Bowls. ... Meanwhile, my room at the Seal Rock Inn is [now] filling up with people who seem on the verge of hysteria at the sight of me still sitting here wasting time on a rambling introduction, with the final chapter still unwritten and the presses scheduled to start rolling in twenty-four hours . . . . but unless somebody shows up pretty soon with extremely powerful speed, there might not be a final chapter. About four fingers of king-hell Crank would do the trick, but I am not optimistic."

In Science

Famous mathematician Paul Erdős took amphetamines, and once won a bet from his friend Ron Graham, who bet him $500 that he could not stop taking the drug for a month.[76] Erdos won the bet, but complained during his abstinence that mathematics had been set back by a month: "Before, when I looked at a piece of blank paper my mind was filled with ideas. Now all I see is a blank piece of paper." After he won the bet, he promptly resumed his amphetamine habit.

In music

Many songs have been written about amphetamine, most notably in the track entitled "St. Ides Heaven" from singer/songwriter, Elliott Smith's self-titled album. It has also influenced the aesthetics of many rock'n'roll bands (especially in the garage rock, mod R&B, death rock, punk/hardcore, gothic rock and extreme heavy metal genres). The Jesus And Mary Chain's use of distortion and feedback was heavily influenced by their use of amphetamine, along with their highly confrontational stage shows early in their existence. This lead them to be banned from venues, even starting riots. Like JAMC, The Who were keen amphetamine users early in their existence, especially Keith Moon, whose drumming style was possibly influenced by it.[citation needed]

The Who's 1965 iconic Mod/youth anthem My Generation, famously re-creates in Roger Daltrey's vocals, the effect of amphetamine on the ability to speak. The pills accelerate the brain's processes to the degree that ideas flow faster than the ability to communicate them by speech, resulting in the characteristic stuttering of words. At various times, in the period 1965-66, either to avoid controversy or to keep the true drug-related reason a secret among "those in the know", Pete Townshend stated the stuttering was a protest at the government's poor record of national education opportunities. However, several years later he later spilled the beans that it mimicked someone under the effect of amphetamine.[citation needed]

Many rock'n'roll bands have named themselves after amphetamine and drug slang surrounding it. For example Mod revivalists, The Purple Hearts named themselves after the amphetamine tablets popular with mods during the 1960s, as did the Australian band of the same name during the mid 1960's. The Amphetameanies, a ska-punk band, are also named after amphetamine, but also intimate it's effects. Motorhead named themselves after the slang for an amphetamine addict. Interestingly, Lemmy Kilmister, said amphetamine was the only drug that he found any benefit in using, saying:

" first got into speed because it was a utilitarian drug and kept you awake when you needed to be awake, when otherwise you'd just be flat out on your back. If you drive to Glasgow for nine hours in the back of a sweaty truck you don't really feel like going onstage feeling all bright and breezy... It's the only drug I've found that I can get on with, and I've tried them all — except smack and morphine: I've never fixed anything."

The amphetamine use and experience or perception of high energy and electronic dance music, particularly the more rapid-tempo genres like gabber and drum and bass, has long been associated with consumption of amphetamine.

In film

Many films have been created that are either visually or aesthetically influenced by the perceived effects of amphetamine, or that portray amphetamine use in their plotlines.[citation needed]

A Scanner Darkly (as well as the novel of the same name) contains a scene where the character Charles Freck suffers from formication.[citation needed]

In television

Advertising has also alluded to and portrayed the effects of amphetamine in both serious and humorous ways, especially in anti-drug campaigns.[citation needed]

On the other hand, advertisements for Red bull energy drinks often allude to effects similar to amphetamine in a tongue-in-cheek manner, with the slogan "Red bull gives you wings". One American anti-drug public information film uses humor, parodying a Folgers coffee jingle to raise awareness of the effects of amphetamine abuse.[77][citation needed]

The BBC drama Ashes to Ashes featured a group of Gypsies who were using amphetamine.[citation needed]

Legal issues

- In the United Kingdom, amphetamines are regarded as Class B drugs. The maximum penalty for unauthorized possession is five years in prison and an unlimited fine. The maximum penalty for illegal supply is fourteen years in prison and an unlimited fine. Methamphetamine has recently been reclassified to Class A, penalties for possession of which are more severe (7 years in prison and an unlimited fine).[78]

- In the Netherlands, amphetamine and methamphetamine are List I drugs of the Opium Law, but the dextro isomer of amphetamine is indicated for ADD/ADHD and narcolepsy and available for prescription as 5 and 10 mg generic tablets, and 5 and 10 mg gel capsules.

- In the United States, amphetamine and methamphetamine are Schedule II drugs, classified as CNS (central nervous system) stimulants.[79] A Schedule II drug is classified as one that has a high potential for abuse, has a currently-accepted medical use and is used under severe restrictions, and has a high possibility of severe psychological and physiological dependence.

Internationally, amphetamine is a Schedule II drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[80]

See also

- Adderall

- Amphetamine psychosis

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Benzylpiperazine

- Clandestine chemistry

- Ethylamphetamine

- Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine)

- Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse)

- Methamphetamine (Desoxyn)

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta)

- Phenethylamines

- Propylamphetamine

- Psychostimulants

- Releasing Agents

References and notes

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Rang and Dale, Pharmacology

- ^ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2008). Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe (PDF). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 48. ISBN 978-92-9168-324-6.

- ^ Edeleanu L. "Uber einige Derivate der Phenylmethacrylsaure und der Phenylisobuttersaure". Ber Deutsch Chem Ges. 1887;Vol 20:616.

- ^ Shulgin, Alexander (1992). "6 – MMDA". PiHKAL. Berkeley, California: Transform Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-9630096-0-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rasmussen N (2006). "Making the first anti-depressant: amphetamine in American medicine, 1929-1950". J Hist Med Allied Sci. 61 (3): 288–323. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrj039. PMID 16492800.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Iverson, Leslie. Speed, Ecstacy, Ritalin: the science of amphetamines. Oxford, New York. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- ^ Rasmussen, Nicolas (2008). "Ch. 4". On Speed: The Many Lives of Amphetamine. New York, New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7601-9.

- ^ Clement, Beverly A., Goff, Christina M. and Forbes, T. David A. (1998). Toxic amines and alkaloids from Acacia rigidula. Phytochemistry 49(5), pp 1377-1380

- ^ Clement, Beverly A., Goff, Erik Allen Burt, Christina M. and Forbes, T. David A. (1997). Toxic amines and alkaloids from Acacia berlandieri. Phytochemistry 46(2), pp 249-254

- ^ Ask Dr. Shulgin Online: Acacias and Natural Amphetamine

- ^ "Air force rushes to defend amphetamine use". The Age. January 18 2003. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ [2] FDA PDF 2004

- ^ http://www.wecarethechildren.org.uk/amphet.html

- ^ a b Jones S, Kornblum JL, Kauer JA (2000). "Amphetamine blocks long-term syfefeffenaptic depression in thefef ventral tegmental area". J. Neurosci. 20 (15): 5575–80. PMID 10908593.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Moore KE (1977). "The actions of amphetamine on neurotransmitters: a brief review". Biol. Psychiatry. 12 (3): 451–62. PMID 17437.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Del Arco A, González-Mora JL, Armas VR, Mora F (1999). "Amphetamine increases the extracellular concentration of glutamate in striatum of the awake rat: involvement of high affinity transporter mechanisms". Neuropharmacology. 38 (7): 943–54. doi:10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00043-X. PMID 10428413.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Drevets WC, Gautier C, Price JC; et al. (2001). "Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in human ventral striatum correlates with euphoria". Biol. Psychiatry. 49 (2): 81–96. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01038-6. PMID 11164755.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wise, RA. “Brain reward circuitry and addiction.” Program and abstracts of the American Society of Addiction Medicine 2003 The State of the Art in Addiction Medicine; October 30-November 1, 2003; Washington, DC. Session

- ^ a b c Sulzer D, Chen TK, Lau YY, Kristensen H, Rayport S, Ewing A (1995). "Amphetamine redistributes dopamine from synaptic vesicles to the cytosol and promotes reverse transport". J. Neurosci. 15 (5 Pt 2): 4102–8. PMID 7751968.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kuczenski R, Segal DS (1997). "Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine". J. Neurochem. 68 (5): 2032–7. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052032.x. PMID 9109529.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2006). "Balance between dopamine and serotonin release modulates behavioral effects of amphetamine-type drugs". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1074: 245–60. doi:10.1196/annals.1369.064. PMID 17105921.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Johnson LA, Guptaroy B, Lund D, Shamban S, Gnegy ME (2005). "Regulation of amphetamine-stimulated dopamine efflux by protein kinase C beta". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (12): 10914–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M413887200. PMID 15647254.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Kahlig KM, Binda F, Khoshbouei H; et al. (2005). "Amphetamine induces dopamine efflux through a dopamine transporter channel". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (9): 3495–500. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407737102. PMC 549289. PMID 15728379.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Public Library of Science. “A mechanism for amphetamine-induced dopamine overload.” PLoS Biol. 3 (2004).

- ^ a b c d Jones S, Kauer JA (1999). "Amphetamine depresses excitatory synaptic transmission via serotonin receptors in the ventral tegmental area". J. Neurosci. 19 (22): 9780–7. PMID 10559387.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Hilber B, Scholze P, Dorostkar MM; et al. (2005). "Serotonin-transporter mediated efflux: a pharmacological analysis of amphetamines and non-amphetamines". Neuropharmacology. 49 (6): 811–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.008. PMID 16185723.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Florin SM, Kuczenski R, Segal DS (1994). "Regional extracellular norepinephrine responses to amphetamine and cocaine and effects of clonidine pretreatment". Brain Res. 654 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(94)91570-9. PMID 7982098.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ WikiAnswers google cached page: 'Does Namenda memantine work in preventing tolerance to adderall ADD amphetamine type drugs?'

- ^ Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A (2005). "Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review". Prog. Neurobiol. 75 (6): 406–33. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. PMID 15955613.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reese EA, Bunzow JR, Arttamangkul S, Sonders MS, Grandy DK (2007). "Trace amine-associated receptor 1 displays species-dependent stereoselectivity for isomers of methamphetamine, amphetamine, and para-hydroxyamphetamine". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 321 (1): 178–86. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.115402. PMID 17218486.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Erowid Amphetamines Vault: Effects

- ^ Amphetamine; Facts

- ^ Amphetamines - Better Health Channel

- ^ adderall xr, adderall medication, adderall side effects, adderall abuse

- ^ Whenever I take speed my penis appears to shrink. Is there a link? What's going on?

- ^ Westover AN, Nakonezny PA, Haley RW (2008). "Acute myocardial infarction in young adults who abuse amphetamines". Drug Alcohol Depend. 96 (1–2): 49–56. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.027. PMID 18353567.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Newswise: Study Finds Link Between Amphetamine Abuse and Heart Attacks in Young Adults Retrieved on June 3, 2008.

- ^ Amphetamine Side Effects drugs.com

- ^ Symptoms of Amphetamine withdrawal - WrongDiagnosis.com

- ^ "Amphetamines: Drug Use and Abuse: Merck Manual Home Edition" (html). Merck. Retrieved February 28 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Reference on lack of physical dependence.

- ^ Leith N, Kuczenski R (1981). "Chronic amphetamine: tolerance and reverse tolerance reflect different behavioral actions of the drug". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 15 (3): 399–404. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(81)90269-0. PMID 7291243.

- ^ Chaudhry I, Turkanis S, Karler R (1988). "Characteristics of "reverse tolerance" to amphetamine-induced locomotor stimulation in mice". Neuropharmacology. 27 (8): 777–81. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(88)90091-3. PMID 3216957.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chronic Amphetamine Use and Abuse

- ^ Sax KW, Strakowski SM (2001). "Behavioral sensitization in humans". J Addict Dis. 20 (3): 55–65. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(95)00497-1. PMID 11681593.

- ^ I. Boileau, A. Dagher, M. Leyton, R. N. Gunn, G. B. Baker, M. Diksic and C. Benkelfat (2006). "Modeling Sensitization to Stimulants in Humans: An [11C]Raclopride/Positron Emission Tomography Study in Healthy Men". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 63 (12): 1386–1395. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1386. PMID 17146013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Twohey, Megan (2006-03-25). "Pills become an addictive study aid". JS Online. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ The Illicit Market for ADHD Prescription Drugs in Queensland (PDF), Queensland Crime and Misconduct Commission, April 2002, retrieved 2008-01-13

- ^ De Mondenard, Dr Jean-Pierre: Dopage, l'imposture des performances, Chiron, France, 2000

- ^ Grant, D.N.W.; Air Force, UK, 1944

- ^ Yesalis, Charles E. (2005-12). "Anabolic Steroid and Stimulant Use in North American Sport between 1850 and 1980". Sport in History. 25 (3): 434–451. doi:10.1080/17460260500396251. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b National Collegiate Athletic Association (2006-01), NCAA Study of Substance Use Habits of College Student-Athletes (PDF), National Collegiate Athletic Association, pp. 2–4, 11–13, retrieved 2007-12-02

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Margaria, R (1964-07-01). "The effect of some drugs on the maximal capacity of athletic performance in man". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 20 (4): 281–287. doi:10.1007/BF00697020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Frias, Carlos (2006-04-02). "Baseball and amphetamines". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Kreidler, Mark (2005-11-15). "Baseball finally brings amphetamines into light of day". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Klobuchar, Jim (2006-03-31). "Can baseball make a clean sweep?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Associated Press (2007-01-18). "MLB owners won't crack down on 'greenies'". MSNBC.com. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Lund, Adrian K (1989). "Drug Use by Tractor-Trailer Drivers". Drugs in the Workplace: Research and Evaluation Data. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. pp. 47–67.

This study has provided the first objective data regarding the use of potentially abusive drugs by tractor-trailer drivers... Prescription stimulants, such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, and phentermine were found in 5 percent of the [317] drivers [who participated in the study], often in combination with similar but less potent stimulants, such as phenylpropanolamine. Nonprescription stimulants were detected in 12 percent of the drivers, about half of whom gave no medical explanation for their presence... One limitation of these findings is that 12 percent of the randomly selected drivers refused to participate in the study or provided insufficient urine and blood for testing; the distribution of drugs among these 42 drivers is unknown... Finally, the results apply to tractor-trailer drivers operating on a major east-west interstate route in Tennessee. Drug incidence among other truck-driver populations are unknown and may be higher or lower than reported here. (64)

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Yablonsky 1968, pp. 243, 257

- ^ Ecstasy MDMA and other ring-substituted amphetamines: a global review: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence: World Health Organization: Geneva UNWHO/MSD/MSB/01.3: 2001

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4604047.stm

- ^ Tri Tong, Dr Edward Boyer, Club drugs, smart drugs, raves, and circuit parties: An overview of the club scene, Pediatric Emergency Care, 0749-5161/02/1803-0216 Vol. 18, No. 3, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc.2002 DOI: 10.1097/01.pec.0000019230.25165.b4

- ^ Miles McNall, PhD; Gary Remafedi, MD, MPH. Relationship of Amphetamine and Other Substance Use to Unprotected Intercourse Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/VOL 153, NOV 1999 [3]

- ^ Naomi Braine, Don C. Des Jarlais, Cullen Goldblatt, Cathy Zadoretzky, Charles Turner HIV Risk Behavior Among Amphetamine Injectors at U.S. Syringe Exchange Programs in AIDS Education and Prevention Volume: 17 | Issue: 6 December 2005 Page(s): 515-524, ISSN: 0899-9546

- ^ Naomi Braine, Don C. Des Jarlais, Cullen Goldblatt, Cathy Zadoretzky, Charles Turner HIV Risk Behavior Among Amphetamine Injectors at U.S. Syringe Exchange Programs in AIDS Education and Prevention Volume: 17 | Issue: 6 December 2005 Page(s): 515-524, ISSN: 0899-9546

- ^ Living on the Edge, Fact Sheet on Depression: Medius Institute: [4]

- ^ Paone D, Des Jarlais DC, Gangloff R, et al. Syringe exchange: HIV prevention, key findings, and future directions in HIV/AIDS. Drug and Alcohol: International Journal of the Addictions 1995; 30(12): 1647-1683.

- ^ Paone D, Des Jarlais DC, Gangloff R, et al. Syringe exchange: HIV prevention, key findings, and future directions in HIV/AIDS. Drug and Alcohol: International Journal of the Addictions 1995; 30(12): 1647-1683.

- ^ Lawrence S. Neinstein, Catherine M Gordon, Debra K Katzman, David S Rosen, Elizabeth R WoodsAdolescent Health Care: A Practical Guide: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007 ISBN 0781792568: 1152 pages

- ^ Gyenis, Attila (1997), Forty Years of On the Road 1957-1997, retrieved 18 March 2008

- ^ Welsh, Irvine (2006-08-10). "Drug Cultures in Trainspotting and Porno". irvinewelsh.net. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Carr, David (29 June 2008). "Fear and Loathing on a Documentary Screen". New York Times. pp. AR7. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Thompson, Hunter S. (1973). Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72. New York: Warner Books. pp. 15–16, 21. ISBN 0-446-31364-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hill, J. Paul Erdos, Mathematical Genius, Human (In That Order)

- ^ [5], YouTube video of the commercial.

- ^ "Class A, B and C drugs". Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ "Trends in Methamphetamine/Amphetamine Admissions to Treatment: 1993-2003" (html). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved February 28 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. Retrieved November 19 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help)

External links

- CID 5826 from PubChem (D-form—dextroamphetamine)

- CID 3007 from PubChem (L-form and D, L-forms)

- CID 32893 from PubChem (L-form—Levamphetamine or L-amphetamine)

- List of 504 Compounds Similar to Amphetamine (PubChem)

- EMCDDA drugs profile: Amphetamine (2007)

- Drugs.com - Amphetamine

- Asia & Pacific Amphetamine-Type Stimulants Information Centre