Ali Farzat

Ali Farzat | |

|---|---|

علي فرزات | |

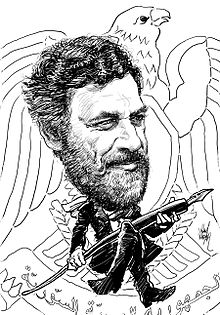

Ali Ferzat by Michael Netzer | |

| Born | 22 June 1951 |

| Nationality | Syrian |

| Education | Damascus University |

| Known for | Political cartoon |

| Awards | Sakharov Prize (2011) Prince Claus Award (2002) |

| Website | www.ali-ferzat.com |

Ali Farzat or Ali Ferzat (Arabic: علي فرزات; born 22 June 1951) is a Syrian political cartoonist. He has published more than 15,000 caricatures in Syrian, Arab and international newspapers.[1] He serves as the head of the Arab Cartoonists Association. In 2011, he received Sakharov Prize for peace.[2] Farzat was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine in 2012.[3]

Life and career

[edit]Farzat was born and raised in the city of Hama, in central Syria on 22 June 1951.[4] At the age of 12, he started publishing drawings professionally on the front pages of al-Ayyam newspaper, shortly before it was banned by the ruling Baath Party.[1] His first cartoon was about the Évian Accords negotiations between Algerians and French officials.[5] In 1969, he began drawing caricatures for the state-run daily, al-Thawra. He enrolled at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Damascus University in 1970, and left before dropping out in 1973.[4][5] In the mid-1970s, he moved to another government controlled daily, Tishreen, where his cartoons appeared every day.[1] His caricatures were critical of government corruption but were not directed at particular individuals.[5] International recognition followed in 1980 when he won the first prize at the Intergraphic International Festival in Berlin, Germany, and his drawings began to appear in the French newspaper Le Monde.[4] His exhibition in 1989 at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, France led to a death threat from Saddam Hussein,[1] and a ban from Iraq, Jordan and Libya.[4] The drawing that brought about the most controversy was called The General and the Decorations which showed a general handing out military decorations instead of food to a hungry Arab citizen.[6]

Farzat met Syrian president Bashar al-Assad prior to his presidency in 1996. According to Farzat, "He [Bashar] actually laughed at some of the cartoons—specifically at those targeting security personnel—he had a bunch of them with him and he turned to them and said: 'Hey, he is making fun of you. What do you think?" Afterward the two developed a friendship.[7] In December 2000, Farzat started publishing al-Domari (Arabic: الدومري, lit. 'The Lamplighter'), which was the first independent periodical in Syria since the Baath Party came to power in 1963. The newspaper was based on political satire and styled in a similar way to the French weekly Le Canard enchaîné. The first issue of the paper came out in February 2001 and the entire 50,000 copies were sold in less than four hours. In 2002, he won the prestigious Dutch Prince Claus Award for "achievement in culture and development". By 2003, however, frequent government censorship and lack of funds forced Farzat to close down al-Domari.[1] He has been called "one of the most famous cultural figures in the Arab world".[8] In December 2012, Farzat was awarded Gebran Tueni prize in Lebanon.[9]

Syrian Civil War

[edit]During the ongoing Syrian Civil War, Farzat had been more direct in his anti-government cartoons, specifically targeting government figures, particularly al-Assad. Following the fall of Tripoli in late August to anti-government rebels seeking to topple Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi, Farzat published a cartoon depicting a sweaty Bashar al-Assad clutching a briefcase running to catch a ride with Gaddafi who is anxiously driving a getaway car. Other cartoons Farzat published previously include one where al-Assad is whitewashing the shadow of large Syrian security force officer while the actual officer remains untouched with the caption reading "Lifting the emergency law" and another showing al-Assad dressed in a military uniform flexing his arm in front of a mirror. The mirror's reflection shows Assad being a dominant muscular figure contrasting with his actual slim stature.[10]

On 25 August 2011, Farzat was reportedly pulled from his vehicle in Umayyad Square in central Damascus by masked gunmen believed to be part of the security forces and a pro-government militia. The men assaulted him, focusing mainly on his hands, and dumped him on the side of the airport road where passersby found him and took him to a hospital.[10][11][12] According to one of his relatives, the security forces notably targeted his hands with both being broken and then told Farzat it was "just a warning".[13] His brother As'aad, however, claims Farzat was kidnapped from his home around 5 am by five gunmen and then taken to the airport road after being beaten "savagely". The gunmen then warned him "not to satirize Syria's leaders". The Local Coordination Committee (LCC), an activist group representing the rebellion in Syria, stated that his briefcase and the drawings in them were confiscated by the assailants.[11]

In response to news of Farzat's ordeal, Syrian opposition members expressed outrage and several online activists changed their Facebook profile picture with that of a hospitalized Farzat in solidarity with the cartoonist.[13] The incident provoked an outpouring of solidarity by cartoonists in the Arab world and internationally. Egyptian Al Sharouk's Waleed Taher had drawn a map of the Arab world with a face emerging out of Syria screaming "They beat up Ali Farzat, World!" Egypt's Al Masry Al Youm published a cartoon depicting a man with two amputated hands, taken aback by how another person guessed that he was a cartoonist. In the Lebanese daily Al Akhbar Nidal al-Khairy published a cartoon depicting Farzat's broken hand being stabbed by three security men smaller than the hand in size with the caption reading "The hands of the people are above their hands." Well-known Carlos Latuff of Brazil drew a rifle with a pen as its barrel pursuing a frantic al-Assad.[14]

The United States condemned the attack calling it "targeted, brutal".[15][16] According to the BBC's Arab affair's analyst, Farzat's beating is a sign that the Syrian authorities "tolerance for dissent is touching zero."[10] One month earlier, Ibrahim al-Qashoush, the alleged composer of a popular anti-government song, was found dead with his vocal cords removed.[8]

Following the attack Farzat stated that he would not meet with al-Assad any longer, although he was not sure if al-Assad directly ordered the assault against him. Farzat said he would continue to criticize al-Assad, stating "I was born to be a cartoonist, to oppose, to have differences with governments that do these bad things. This is what I do."[7]

Style

[edit]Farzat's drawings are centred around themes involving criticism of bureaucracy, corruption and hypocrisy within the government and the wealthy elite. His drawings, typically without captions, are noted for their scathing criticism and for depicting types rather than individuals.[1] Through his cutting caricatures he gained the respect of many Arabs while drawing the ire of their governments.[15] However, since the uprising in Syria began Farzat has been more direct in his caricatures, depicting actual figures including the President of Syria, Bashar al-Assad.[10]

Collections

[edit]- A Pen of Damascus Steel: The Political Cartoons of an Arab Master (2005) Published by Cune Press www.cunepress.com

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Moubayed, Sami M. (2006). Steel & Silk: Men & Women Who Shaped Syria 1900-2000. Cune Press. pp. 532–534. ISBN 1-885942-41-9.

- ^ "Cartooning for Peace - Ali Ferzat wins the 2011 Sakharov Prize". Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Matt, Wuerker (18 April 2012). "Ali Ferzat: The 100 Most Influential People in the World". Time. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Ali Farzat". Cune Press. Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Alsaleh, Asaad (2021). Historical dictionary of the Syrian uprising and civil war. Lanham, Maryland. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-5381-2077-4. OCLC 1225067023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Nasser, Nagham (28 March 2008). "رسوم محظورة عربيا في معرض الفنان علي فرزات". Al-Jazeera. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ a b Jones, Owen Bennet. The moral dilemmas of Syria's revolution. BBC News. 11 March 2012. Retrieved on 11 March 2012.

- ^ a b Samira Shackle (August 2011). "Famed Syrian cartoonist has his hands broken". New Statesman.

- ^ "Farzat receives prize for Syrian political cartoons". The Daily Star. 12 December 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Famed Syrian cartoonist 'beaten'". 25 August 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Syrian tanks 'resume shelling' eastern town". Al-Jazeera English. 25 August 2011.

- ^ "Freedom Alert: Syrian Cartoonist Ali Ferzat Attacked". August 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Ali, Nour. "Syrian forces beat up political cartoonist Ali Ferzat". The Guardian. 25 August 2011.

- ^ Outpouring of cartoons in solidarity with Syria's Ali Ferzat/ Ahram Online. Al Ahram Weekly. 30 August 2011.

- ^ a b More deaths as Syrian protests continue. Al-Jazeera. 26 August 2011.

- ^ US condemns Syria political cartoonist attack| aljazeera.net| 26 August 2011

Further reading

[edit]- Cartoonist gives Syria a new line in freedom by Brian Whitaker, Tuesday 3 April 2001, The Guardian

- Hoping for media freedom in Syria, by Dan Isaacs, 25 March 2005, BBC

- 'I Don't Compromise', by Hassan Abdallah, 29 June 2007, Newsweek

- A Wasted Decade, 16 July 2010, Human Rights Watch

- Celebrated cartoonist beaten up in Syria, say activists, 25 August 2011 Now Lebanon

- Ferzat in the Lion's Den, 17 October 2011 Michael Netzer

- Syrian Cartoonist Ali Farzat Recounts Assassination Attempt Following Criticism of President Al-Assad, MEMRITV, Clip No. 4299, 2 June 2014.