Alabama: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 190: | Line 190: | ||

African Americans were presumed partial to Republicans for historical reasons, but they were disfranchised. White Alabamans felt bitter towards the Republican Party in the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction. These factors created a longstanding tradition that any candidate who wanted to be viable with White voters had to run as a Democrat regardless of political beliefs. |

African Americans were presumed partial to Republicans for historical reasons, but they were disfranchised. White Alabamans felt bitter towards the Republican Party in the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction. These factors created a longstanding tradition that any candidate who wanted to be viable with White voters had to run as a Democrat regardless of political beliefs. |

||

Although efforts had already started decades earlier, |

Although efforts had already started decades earlier, Alabama is full of Rednecks began to press to end disfranchisement and segregation in the state during the 1950s and 1960s with the [[African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955–1968)|Civil Rights Movement]]. In 1954 the US Supreme Court ruled in ''[[Brown v. Board of Education]]'' that public schools had to be desegated, but Alabama was slow to comply. The civil rights movement raised national awareness of the issues, leading to the enactment of the [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]] and [[Voting Rights Act of 1965]] by the U.S. Congress. During the 1960s, under Governor [[George Wallace]], failed attempts were made at the state level to resist federally sanctioned [[desegregation]] efforts. |

||

During the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans achieved enforcement of voting and other civil constitutional rights through the passage of the national [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]],<ref name="cra64">{{cite web|url=http://finduslaw.com/civil_rights_act_of_1964_cra_title_vii_equal_employment_opportunities_42_us_code_chapter_21 |title=Civil Rights Act of 1964 |publisher=Finduslaw.com |accessdate=October 24, 2010 |archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20101021141154/http://finduslaw.com/civil_rights_act_of_1964_cra_title_vii_equal_employment_opportunities_42_us_code_chapter_21 |archivedate= October 21, 2010 <!--DASHBot--> |deadurl= no}}</ref> and the [[Voting Rights Act of 1965]]. Legal segregation ended in the states as [[Jim Crow laws]] were invalidated or repealed.<ref name="USDOJ">{{cite web|url= http://www.usdoj.gov/kidspage/crt/voting.htm |archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20070221054512/http://www.usdoj.gov/kidspage/crt/voting.htm |archivedate= February 21, 2007 |title= Voting Rights |accessdate =September 23, 2006 |date= January 9, 2002 |work= Civil Rights: Law and History |publisher= U.S.Department of Justice}}</ref> |

During the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans achieved enforcement of voting and other civil constitutional rights through the passage of the national [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]],<ref name="cra64">{{cite web|url=http://finduslaw.com/civil_rights_act_of_1964_cra_title_vii_equal_employment_opportunities_42_us_code_chapter_21 |title=Civil Rights Act of 1964 |publisher=Finduslaw.com |accessdate=October 24, 2010 |archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20101021141154/http://finduslaw.com/civil_rights_act_of_1964_cra_title_vii_equal_employment_opportunities_42_us_code_chapter_21 |archivedate= October 21, 2010 <!--DASHBot--> |deadurl= no}}</ref> and the [[Voting Rights Act of 1965]]. Legal segregation ended in the states as [[Jim Crow laws]] were invalidated or repealed.<ref name="USDOJ">{{cite web|url= http://www.usdoj.gov/kidspage/crt/voting.htm |archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20070221054512/http://www.usdoj.gov/kidspage/crt/voting.htm |archivedate= February 21, 2007 |title= Voting Rights |accessdate =September 23, 2006 |date= January 9, 2002 |work= Civil Rights: Law and History |publisher= U.S.Department of Justice}}</ref> |

||

| Line 223: | Line 223: | ||

South Alabama reports many [[thunderstorms]]. The Gulf Coast, around Mobile Bay, averages between 70 and 80 days per year with thunder reported. This activity decreases somewhat further north in the state, but even the far north of the state reports thunder on about 60 days per year. Occasionally, thunderstorms are severe with frequent [[lightning]] and large [[hail]]; the central and northern parts of the state are most vulnerable to this type of storm. Alabama ranks seventh in the number of deaths from lightning and ninth in the number of deaths from lightning strikes per capita.<ref>[http://www.lightningsafety.com/nlsi_lls/fatalities_us.html Lightning Fatalities, Injuries and Damages in the United States, 1990–2003]. NLSI. Retrieved May 8, 2007.</ref> |

South Alabama reports many [[thunderstorms]]. The Gulf Coast, around Mobile Bay, averages between 70 and 80 days per year with thunder reported. This activity decreases somewhat further north in the state, but even the far north of the state reports thunder on about 60 days per year. Occasionally, thunderstorms are severe with frequent [[lightning]] and large [[hail]]; the central and northern parts of the state are most vulnerable to this type of storm. Alabama ranks seventh in the number of deaths from lightning and ninth in the number of deaths from lightning strikes per capita.<ref>[http://www.lightningsafety.com/nlsi_lls/fatalities_us.html Lightning Fatalities, Injuries and Damages in the United States, 1990–2003]. NLSI. Retrieved May 8, 2007.</ref> |

||

Alabama, along with [[Kansas]], has the most |

Alabama, along with [[Kansas]], has the most rednecks [[Enhanced Fujita scale|EF5 tornadoes]] of any state, according to statistics from the [[National Climatic Data Center]] for the period January 1, 1950, to October 31, 2006.<ref>[http://www.tornadoproject.com/fscale/fscale.htm Fujita scale]. Tornadoproject.com. Retrieved September 3, 2007.</ref> Several long-tracked F5 tornadoes have contributed to Alabama reporting more tornado fatalities than any other state, even surpassing Texas which has a much larger area within [[Tornado Alley]]. The state suffered tremendous damage in the [[Super Outbreak]] of April 1974, and the [[April 25–28, 2011 tornado outbreak]]. The outbreak in April 2011 produced a record amount of tornadoes in the state. The tally reached 62.<ref>{{cite web |last=Oliver |first=Mike |title=April 27's record tally: 62 tornadoes in Alabama |url=http://blog.al.com/spotnews/2011/08/april_27s_record_tally_62_torn.html |publisher=al.com |accessdate=November 4, 2012}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Phil Campbell tornado damage.jpg|thumb|right|Tornado damage in [[Phil Campbell, Alabama|Phil Campbell]] following the statewide [[April 25–28, 2011 tornado outbreak|April 27, 2011 tornado outbreak]].]] |

[[File:Phil Campbell tornado damage.jpg|thumb|right|Tornado damage in [[Phil Campbell, Alabama|Phil Campbell]] following the statewide [[April 25–28, 2011 tornado outbreak|April 27, 2011 tornado outbreak]].]] |

||

| Line 248: | Line 248: | ||

{{Main|Demographics of Alabama}} |

{{Main|Demographics of Alabama}} |

||

{{US |

{{US LOL population |

||

|1800= 1250 |

|1800= 1250 |

||

|1810= 9046 |

|1810= 9046 |

||

|1820= |

|1820= 169691 |

||

|1830= |

|1830= 306927 |

||

|1840= 590756 |

|1840= 590756 |

||

|1850= 771623 |

|1850= 771623 |

||

|1860= 964201 |

|1860= 964201 |

||

|1870= 996992 |

|1870= 996992 |

||

|1880= |

|1880= 1269505 |

||

|1890= |

|1890= 1569691 |

||

|1900= 1828697 |

|1900= 1828697 |

||

|1910= 2138093 |

|1910= 2138093 |

||

Revision as of 15:24, 27 November 2013

Alabama | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Alabama Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | December 14, 1819 (22nd) |

| Capital | Montgomery |

| Largest city | Birmingham 212,237 (2010 census) |

| Largest county or equivalent | Baldwin County |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Greater Birmingham Area |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Robert J. Bentley (R) |

| • Lieutenant governor | Kay Ivey (R) |

| Legislature | Alabama Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. senators | Richard Shelby (R) Jeff Sessions (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 6 Republicans, 1 Democrat (list) |

| Population | |

• Total | 4,822,023 (2,012 est.)[1] |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | English (96.17%) Spanish (2.12%) |

| Traditional abbreviation | Ala. |

| Latitude | 30° 11′ N to 35° N |

| Longitude | 84° 53′ W to 88° 28′ W |

Alabama (/ˌæləˈbæmə/ ) is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama is the 30th-most extensive and the 23rd-most populous of the 50 United States. At 1,300 miles (2,100 km), Alabama has one of the longest navigable inland waterways in the nation.[6]

From the American Civil War until World War II, Alabama, like many Southern states, suffered economic hardship, in part because of continued dependence on agriculture. Despite the growth of major industries and urban centers, White rural interests dominated the state legislature until the 1960s, while urban interests and African Americans were under-represented.[7]

Following World War II, Alabama experienced growth as the economy of the state transitioned from one primarily based on agriculture to one with diversified interests. The establishment or expansion of multiple United States Armed Forces installations added to the state economy and helped bridge the gap between an agricultural and industrial economy during the mid-20th century. The state economy in the 21st century is dependent on management, automotive, finance, manufacturing, aerospace, mineral extraction, healthcare, education, retail, and technology.[8]

Alabama is unofficially nicknamed the Yellowhammer State, after the state bird. Alabama is also known as the "Heart of Dixie". The state tree is the Longleaf Pine, and the state flower is the Camellia. The capital of Alabama is Montgomery. The largest city by population is Birmingham.[9] The largest city by total land area is Huntsville. The oldest city is Mobile, founded by French colonists.[10]

Etymology

The Alabama people, a Muskogean-speaking tribe whose members lived just below the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers on the upper reaches of the Alabama River,[11] were the origin of later European-American naming of the river and state. In the Alabama language, the word for an Alabama person is Albaamo (or variously Albaama or Albàamo in different dialects; the plural form is Albaamaha).[12]

The word Alabama is believed to have come from the related Choctaw language[13] and was adopted by the Alabama tribe as their name.[14] The spelling of the word varies significantly among historical sources.[14] The first usage appears in three accounts of the Hernando de Soto expedition of 1540 with Garcilaso de la Vega using Alibamo, while the Knight of Elvas and Rodrigo Ranjel wrote Alibamu and Limamu, respectively, in efforts to transliterate the term.[14] As early as 1702, the French called the tribe the Alibamon, with French maps identifying the river as Rivière des Alibamons.[11] Other spellings of the appellation have included Alibamu, Alabamo, Albama, Alebamon, Alibama, Alibamou, Alabamu, and Allibamou.[14][15][16][17]

Sources disagree on the meaning of the word. An 1842 article in the Jacksonville Republican proposed that it meant "Here We Rest."[14] This notion was popularized in the 1850s through the writings of Alexander Beaufort Meek.[14] Experts in the Muskogean languages have been unable to find any evidence to support such a translation.[11][14]

Scholars believe the word comes from the Choctaw alba (meaning "plants" or "weeds") and amo (meaning "to cut", "to trim", or "to gather").[13][14][18] The meaning may have been "clearers of the thicket"[13] or "herb gatherers",[18][19] referring to clearing land for cultivation[15] or collecting medicinal plants.[19] The state has numerous place names of Native American origin.[20][21]

History

Pre-European settlement

Indigenous peoples of varying cultures lived in the area for thousands of years before European colonization. Trade with the northeastern tribes via the Ohio River began during the Burial Mound Period (1000 BC–AD 700) and continued until European contact.[22]

The agrarian Mississippian culture covered most of the state from 1000 to 1600 AD, with one of its major centers built at what is now the Moundville Archaeological Site in Moundville, Alabama.[23][24] Analysis of artifacts recovered from archaeological excavations at Moundville were the basis of scholars' formulating the characteristics of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC).[25] Contrary to popular belief, the SECC appears to have no direct links to Mesoamerican culture, but developed independently. The Ceremonial Complex represents a major component of the religion of the Mississippian peoples; it is one of the primary means by which their religion is understood.[26]

Among the historical tribes of Native American people living in the area of present-day Alabama at the time of European contact were the Cherokee, an Iroquoian language people; and the Muskogean-speaking Alabama (Alibamu), Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Koasati.[27] While part of the same large language family, the Muskogee tribes developed distinct cultures and languages.

European settlement

With exploration in the 16th century, the Spanish were the first Europeans to reach Alabama. The expedition of Hernando de Soto passed through Mabila and other parts of the state in 1540. More than 160 years later, the French founded the first European settlement in the region at Old Mobile in 1702.[28] The city was moved to the current site of Mobile in 1711. This area was claimed by the French from 1702 to 1763 as part of La Louisiane.[29]

After the French lost to the British in the Seven Years War, it became part of British West Florida from 1763 to 1783. After the United States victory in the American Revolutionary War, the territory was divided between the United States and Spain. The latter retained control of this western territory from 1783 until the surrender of the Spanish garrison at Mobile to U.S. forces on April 13, 1813.[29][30]

Thomas Bassett, a loyalist to the British monarchy during the Revolutionary era, was one of the earliest White settlers in the state outside of Mobile. He settled in the Tombigbee District during the early 1770s.[31] The boundaries of the district were roughly limited to the area within a few miles of the Tombigbee River and included portions of what is today southern Clarke County, northernmost Mobile County, and most of Washington County.[32][33]

What is now the counties of Baldwin and Mobile became part of Spanish West Florida in 1783, part of the independent Republic of West Florida in 1810, and was finally added to the Mississippi Territory in 1812. Most of what is now the northern two-thirds of Alabama was known as the Yazoo lands beginning during the British colonial period. It was claimed by the Province of Georgia from 1767 onwards. Following the Revolutionary War, it remained a part of Georgia, although heavily disputed.[34][35]

With the exception of the immediate area around Mobile and the Yazoo lands, what is now the lower one-third Alabama was made part of the Mississippi Territory when it was organized in 1798. The Yazoo lands were added to the territory in 1804, following the Yazoo land scandal.[35][36] Spain kept a claim on its former Spanish West Florida territory in what would become the coastal counties until the Adams–Onís Treaty officially ceded it to the United States in 1819.[30]

19th century

Prior to the admission of Mississippi as a state on December 10, 1817, the more sparsely settled eastern half of the territory was separated and named the Alabama Territory. The Alabama Territory was created by the United States Congress on March 3, 1817. St. Stephens, now abandoned, served as the territorial capital from 1817 to 1819.[37]

The U.S. Congress selected Huntsville as the site for the first Constitutional Convention of Alabama after it was approved to become the 22nd state. From July 5 to August 2, 1819, delegates met to prepare the new state constitution. Huntsville served as the temporary capital of Alabama from 1819 to 1820, when the seat of state government was moved to Cahaba in Dallas County.[38]

Cahaba, now a ghost town, was the first permanent state capital from 1820 to 1825.[39] Alabama Fever was already underway when the state was admitted to the Union, with settlers and land speculators pouring into the state to take advantage of fertile land suitable for cotton cultivation.[40][41][42] Part of the frontier in the 1820s and 1830s, its constitution provided for universal suffrage for White men.[43]

Southeastern planters and traders from the Upper South brought slaves with them as the cotton plantations in Alabama expanded. The economy of the central Black Belt (named for its dark, productive soil) was built around large cotton plantations whose owners' wealth grew largely from slave labor.[43] The area also drew many poor, disfranchised people who became subsistence farmers. Alabama had a population estimated at under 10,000 people in 1810, but it had increased to more than 300,000 people by 1830.[40] Most Native American tribes were completely removed from the state within a few years of the passage of the Indian Removal Act by Congress in 1830.[44]

From 1826 to 1846, Tuscaloosa served as the capital of Alabama. On January 30, 1846, the Alabama legislature announced that it had voted to remove the capital city from Tuscaloosa to Montgomery. The first legislative session in the new capital met in December 1847.[45] A new capitol building was erected under the direction of Stephen Decatur Button of Philadelphia. The first structure burned down in 1849, but was rebuilt on the same site in 1851. This second capitol building in Montgomery remains to the present day. It was designed by Barachias Holt of Exeter, Maine.[46][47] By 1860 the population had increased to a total of 964,201 people, of which 435,080 were enslaved African Americans and 2,690 were free people of color.[48]

On January 11, 1861, Alabama declared its secession from the Union. After remaining an independent republic for a few days, it joined the Confederate States of America. The Confederacy's capital was initially located at Montgomery. Alabama was heavily involved in the American Civil War. Although comparatively few battles were fought in the state, Alabama contributed about 120,000 soldiers to the war effort.

A company of cavalry soldiers from Huntsville, Alabama joined Nathan Bedford Forrest's battalion in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. The company wore new uniforms with yellow trim on the sleeves, collar and coat tails. This led to them being greeted with "Yellowhammer", and the name later was applied to all Alabama troops in the Confederate Army.[49]

Alabama's slaves were freed by the 13th Amendment in 1865.[50] Alabama was under military rule from the end of the war in May 1865 until its official restoration to the Union in 1868. From 1867 to 1874, with most White citizens barred from voting, many African Americans emerged as political leaders in the state. Alabama was represented in Congress during this period by three African American congressmen: Jeremiah Haralson, Benjamin S. Turner, and James T. Rapier.[51]

Following the war, the state remained chiefly agricultural, with an economy tied to cotton. During Reconstruction, state legislators ratified a new state constitution in 1868 that created a public school system for the first time and expanded women's rights. Legislators funded numerous public road and railroad projects, although these were plagued with allegations of fraud and misappropriation.[51] Organized resistance groups also tried to suppress the freedmen and Republicans. Besides the short-lived original Ku Klux Klan, these included the Pale Faces, Knights of the White Camellia, Red Shirts, and the White League.[51]

Reconstruction in Alabama ended in 1874, when the Democrats regained control of the legislature and governor's office. They wrote another constitution in 1875,[51] and the legislature passed the Blaine Amendment, prohibiting public money from being used to finance religious affiliated schools.[52] The same year, legislation was approved that called for racially segregated schools.[53] Railroad passenger cars were segregated in 1891.[53] More Jim Crow laws were passed at the beginning of the 20th century to enforce segregation in everyday life.

20th century

The new 1901 Constitution of Alabama included electoral laws that effectively disfranchised African Americans, Native Americans, and most poor Whites through voting restrictions, including poll taxes and literacy requirements.[54] While the planter class had persuaded poor Whites to support these legislative efforts, the new restrictions resulted in their disfranchisement as well, due mostly to the imposition of a cumulative poll tax.[55]

In 1900, Alabama had more than 181,000 African Americans eligible to vote. By 1903, only 2,980 were qualified to register, although at least 74,000 African-American voters were literate.[55] By 1941, more White Alabamians than African-American residents had been disfranchised: a total of 600,000 Whites to 520,000 African Americans.[55] Nearly all African Americans had lost the ability to vote, a situation that persisted until after passage of federal civil rights legislation in the 1960s to enforce their constitutional rights as citizens.

The 1901 constitution reiterated that schools be racially segregated. It also restated that interracial marriage was illegal, although such marriages had been made illegal in 1867. Further racial segregation laws were passed related to public facilities into the 1950s: jails were segregated in 1911; hospitals in 1915; toilets, hotels, and restaurants in 1928; and bus stop waiting rooms in 1945.[53]

The rural-dominated Alabama legislature consistently underfunded schools and services for the disfranchised African Americans, but it did not relieve them of paying taxes.[43] Partially as a response to chronic underfunding of education for African Americans in the South, the Rosenwald Fund began funding the construction of what came to be known as Rosenwald Schools. In Alabama these schools were designed and the construction partially financed with Rosenwald funds, which paid one-third of the construction costs. The local community and state raised matching funds to pay the rest. Black residents effectively taxed themselves twice, by raising additional monies to supply matching funds for such schools, which were built in many rural areas.[56]

Beginning in 1913, the first 80 Rosenwald Schools were built in Alabama for African-American children. A total of 387 schools, seven teacher's houses, and several vocational buildings had been completed in the state by 1937. Several of the surviving school buildings in the state are now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[56]

Continued racial discrimination, agricultural depression, and the failure of the cotton crops due to boll weevil infestation led tens of thousands of African Americans to seek opportunities in northern cities. They left Alabama in the early 20th century as part of the Great Migration to industrial jobs and better futures in northern and midwestern industrial cities. Reflecting this emigration, the population growth rate in Alabama (see "Historical Populations" table below) dropped by nearly half from 1910 to 1920.

At the same time, many rural people, both White and African American, moved to the city of Birmingham to work in new industrial jobs. Birmingham experienced such rapid growth that it was called "The Magic City". By the 1920s, Birmingham was the 19th-largest city in the United States and had more than 30% of the Alabama's population. Heavy industry and mining were the basis of its economy.[57] Its residents were under-represented for decades in the state legislature, which refused to redistrict to recognize demographic changes, such as urbanization.

Industrial development related to the demands of World War II brought a level of prosperity to the state not seen since before the Civil War.[43] Rural workers poured into the largest cities in the state for better jobs and a higher standard of living. One example of this massive influx of workers can be shown by what happened in Mobile. Between 1940 and 1943, more than 89,000 people moved into the city to work for war effort industries.[58] Cotton and other cash crops faded in importance as the state developed a manufacturing and service base.

Despite massive population changes in the state from 1901 to 1961, the rural-dominated legislature refused to reapportion House and Senate seats based on population. They held on to old representation to maintain political and economic power in agricultural areas. In addition, the state legislature gerrymandered the few Birmingham legislative seats to ensure election by persons living outside Birmingham.

One result was that Jefferson County, containing Birmingham's industrial and economic powerhouse, contributed more than one-third of all tax revenue to the state, but did not receive a proportional amount in services. Urban interests were consistently underrepresented in the legislature. A 1960 study noted that because of rural domination, "A minority of about 25 per cent of the total state population is in majority control of the Alabama legislature."[7]

African Americans were presumed partial to Republicans for historical reasons, but they were disfranchised. White Alabamans felt bitter towards the Republican Party in the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction. These factors created a longstanding tradition that any candidate who wanted to be viable with White voters had to run as a Democrat regardless of political beliefs.

Although efforts had already started decades earlier, Alabama is full of Rednecks began to press to end disfranchisement and segregation in the state during the 1950s and 1960s with the Civil Rights Movement. In 1954 the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that public schools had to be desegated, but Alabama was slow to comply. The civil rights movement raised national awareness of the issues, leading to the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 by the U.S. Congress. During the 1960s, under Governor George Wallace, failed attempts were made at the state level to resist federally sanctioned desegregation efforts.

During the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans achieved enforcement of voting and other civil constitutional rights through the passage of the national Civil Rights Act of 1964,[59] and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Legal segregation ended in the states as Jim Crow laws were invalidated or repealed.[60]

Under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, cases were filed in Federal courts to force Alabama to redistrict by population both the House and Senate of the state legislature. In 1972, for the first time since 1901, the legislature implemented the Alabama constitution's provision for periodic redistricting based on population. This benefited the urban areas that had developed, as well as all in the population who had been underrepresented for more than 60 years.[7]

Geography

Alabama is the thirtieth-largest state in the United States with 52,419 square miles (135,760 km2) of total area: 3.2% of the area is water, making Alabama 23rd in the amount of surface water, also giving it the second-largest inland waterway system in the U.S.[61] About three-fifths of the land area is a gentle plain with a general descent towards the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. The North Alabama region is mostly mountainous, with the Tennessee River cutting a large valley creating numerous creeks, streams, rivers, mountains, and lakes.[62]

The states bordering Alabama are Tennessee to the north; Georgia to the east; Florida to the south; and Mississippi to the west. Alabama has coastline at the Gulf of Mexico, in the extreme southern edge of the state.[62] Alabama ranges in elevation from sea level[63] at Mobile Bay to over 1,800 feet (550 m) in the Appalachian Mountains in the northeast.

The highest point is Mount Cheaha,[62] at a height of 2,413 ft (735 m).[64] Alabama's land consists of 22 million acres (89,000 km2) of forest or 67% of total land area.[65] Suburban Baldwin County, along the Gulf Coast, is the largest county in the state in both land area and water area.[66]

Areas in Alabama administered by the National Park Service include Horseshoe Bend National Military Park near Alexander City; Little River Canyon National Preserve near Fort Payne; Russell Cave National Monument in Bridgeport; Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site in Tuskegee; and Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site near Tuskegee.[67]

Additionally, Alabama has four National Forests: Conecuh, Talladega, Tuskegee, and William B. Bankhead.[68] Alabama also contains the Natchez Trace Parkway, the Selma To Montgomery National Historic Trail, and the Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail. A notable natural wonder in Alabama is "Natural Bridge" rock, the longest natural bridge east of the Rockies, located just south of Haleyville.

A 5-mile (8 km)-wide meteorite impact crater is located in Elmore County, just north of Montgomery. This is the Wetumpka crater, the site of "Alabama's greatest natural disaster." A 1,000-foot (300 m)-wide meteorite hit the area about 80 million years ago.[69] The hills just east of downtown Wetumpka showcase the eroded remains of the impact crater that was blasted into the bedrock, with the area labeled the Wetumpka crater or astrobleme ("star-wound") because of the concentric rings of fractures and zones of shattered rock that can be found beneath the surface.[70] In 2002, Christian Koeberl with the Institute of Geochemistry University of Vienna published evidence and established the site as 157th recognized impact crater on Earth.[71]

Climate

The state is classified as humid subtropical (Cfa) under the Koppen Climate Classification.[72] The average annual temperature is 64 °F (18 °C). Temperatures tend to be warmer in the southern part of the state with its proximity to the Gulf of Mexico, while the northern parts of the state, especially in the Appalachian Mountains in the northeast, tend to be slightly cooler.[73] Generally, Alabama has very hot summers and mild winters with copious precipitation throughout the year. Alabama receives an average of 56 inches (1,400 mm) of rainfall annually and enjoys a lengthy growing season of up to 300 days in the southern part of the state.[73]

Summers in Alabama are among the hottest in the U.S., with high temperatures averaging over 90 °F (32 °C) throughout the summer in some parts of the state. Alabama is also prone to tropical storms and even hurricanes. Areas of the state far away from the Gulf are not immune to the effects of the storms, which often dump tremendous amounts of rain as they move inland and weaken.

South Alabama reports many thunderstorms. The Gulf Coast, around Mobile Bay, averages between 70 and 80 days per year with thunder reported. This activity decreases somewhat further north in the state, but even the far north of the state reports thunder on about 60 days per year. Occasionally, thunderstorms are severe with frequent lightning and large hail; the central and northern parts of the state are most vulnerable to this type of storm. Alabama ranks seventh in the number of deaths from lightning and ninth in the number of deaths from lightning strikes per capita.[74]

Alabama, along with Kansas, has the most rednecks EF5 tornadoes of any state, according to statistics from the National Climatic Data Center for the period January 1, 1950, to October 31, 2006.[75] Several long-tracked F5 tornadoes have contributed to Alabama reporting more tornado fatalities than any other state, even surpassing Texas which has a much larger area within Tornado Alley. The state suffered tremendous damage in the Super Outbreak of April 1974, and the April 25–28, 2011 tornado outbreak. The outbreak in April 2011 produced a record amount of tornadoes in the state. The tally reached 62.[76]

The peak season for tornadoes varies from the northern to southern parts of the state. Alabama is one of the few places in the world that has a secondary tornado season in November and December, along with the spring severe weather season. The northern part of the state—along the Tennessee Valley—is one of the areas in the U.S. most vulnerable to violent tornadoes. The area of Alabama and Mississippi most affected by tornadoes is sometimes referred to as Dixie Alley, as distinct from the Tornado Alley of the Southern Plains.

Winters are generally mild in Alabama, as they are throughout most of the southeastern U.S., with average January low temperatures around 40 °F (4 °C) in Mobile and around 32 °F (0 °C) in Birmingham. Although snow is a rare event in much of Alabama, areas of the state north of Montgomery may receive a dusting of snow a few times every winter, with an occasional moderately heavy snowfall every few years. Historic snowfall events include New Year's Eve 1963 snowstorm and the 1993 Storm of the Century. The annual average snowfall for the Birmingham area is 2 inches (51 mm) per year. In the southern Gulf coast, snowfall is less frequent, sometimes going several years without any snowfall.

Alabama's highest temperature of 112 °F (44 °C) was recorded on September 5, 1925 in the unincorporated community of Centerville. The record low of −27 °F (−33 °C) occurred on January 30, 1966 in New Market.[77]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huntsville[78] | Average high | 48.9 (9.4) |

54.6 (12.6) |

63.4 (17.4) |

72.3 (22.4) |

79.6 (26.4) |

86.5 (30.3) |

89.4 (31.9) |

89.0 (31.7) |

83.0 (28.3) |

72.9 (22.7) |

61.6 (16.4) |

52.4 (11.3) |

71.1 (21.7) | |

| Average low | 30.7 (-0.7) |

34.0 (1.1) |

41.2 (5.1) |

48.4 (9.1) |

57.5 (14.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

69.5 (20.8) |

68.1 (20.1) |

61.7 (16.5) |

49.6 (9.8) |

40.7 (4.8) |

33.8 (1.0) |

50.1 (10.1) | ||

| Birmingham[79] | Average high | 52.8 (11.6) |

58.3 (14.6) |

66.5 (19.2) |

74.1 (23.4) |

81.0 (27.2) |

87.5 (30.8) |

90.6 (32.6) |

90.2 (32.3) |

84.6 (29.2) |

74.9 (23.8) |

64.5 (18.1) |

56.0 (13.3) |

73.4 (23.0) | |

| Average low | 32.3 (0.2) |

35.4 (1.9) |

42.4 (5.8) |

48.4 (9.1) |

57.6 (14.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

69.7 (20.9) |

68.9 (20.5) |

63.0 (17.2) |

50.9 (10.5) |

41.8 (5.4) |

35.2 (1.8) |

50.9 (10.5) | ||

| Montgomery [80] | Average high | 57.6 (14.2) |

62.4 (16.9) |

70.5 (21.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

84.6 (29.2) |

90.6 (32.6) |

92.7 (33.7) |

92.2 (33.4) |

87.7 (30.9) |

78.7 (25.9) |

68.7 (20.4) |

60.3 (15.7) |

77.0 (25.0) | |

| Average low | 35.5 (1.9) |

38.6 (3.7) |

45.4 (7.4) |

52.1 (11.2) |

60.1 (15.6) |

67.3 (19.6) |

70.9 (21.6) |

70.1 (21.2) |

64.9 (18.3) |

52.2 (11.2) |

43.5 (6.4) |

37.6 (3.1) |

53.2 (11.8) | ||

| Mobile[81] | Average high | 60.7 (15.9) |

64.5 (18.1) |

71.2 (21.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

84.2 (29.0) |

89.4 (31.9) |

91.2 (32.9) |

90.8 (32.7) |

86.8 (30.4) |

79.2 (26.2) |

70.1 (21.2) |

62.9 (17.2) |

77.4 (25.2) | |

| Average low | 39.5 (4.2) |

42.4 (5.8) |

49.2 (9.6) |

54.8 (12.7) |

62.8 (17.1) |

69.2 (20.7) |

71.8 (22.1) |

71.7 (22.0) |

67.6 (19.8) |

56.3 (13.5) |

47.8 (8.8) |

41.6 (5.3) |

56.2 (13.4) | ||

Flora and fauna

Alabama is home to a diverse array of flora and fauna, due largely to a variety of habitats that range from the Tennessee Valley, Appalachian Plateau, and Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians of the north to the Piedmont, Canebrake and Black Belt of the central region to the Gulf Coastal Plain and beaches along the Gulf of Mexico in the south. The state is usually ranked among the top in nation for its range of overall biodiversity.[82][83]

Alabama once boasted huge expanses of pine forest, which still form the largest proportion of forests in the state.[82] It currently ranks fifth in the nation for the diversity of its flora. It is home to nearly 4,000 pteridophyte and spermatophyte plant species.[84]

Indigenous animal species in the state include 62 mammal species,[85] 93 reptile species,[86] 73 amphibian species,[87] roughly 307 native freshwater fish species,[82] and 420 bird species that spend at least part of their year within the state.[88] Invertebrates include 83 crayfish species and 383 mollusk species. 113 of these mollusk species have never been collected outside of the state.[89][90]

Demographics

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Alabama was 4,822,023 on July 1, 2012,[1][91] which represents an increase of 42,287, or 0.9%, since the 2010 Census.[92] This includes a natural increase since the last census of 121,054 people (that is 502,457 births minus 381,403 deaths) and an increase due to net migration of 104,991 people into the state.[92]

Immigration from outside the U.S. resulted in a net increase of 31,180 people, and migration within the country produced a net gain of 73,811 people.[92] The state had 108,000 foreign-born (2.4% of the state population), of which an estimated 22.2% were illegal immigrants (24,000).

The center of population of Alabama is located in Chilton County, outside of the town of Jemison.[93]

Race and ancestry

According to the 2010 Census, Alabama had a population of 4,779,736. The racial composition of the state was 68.5% White (67.0% Non-Hispanic White Alone), 26.2% Black or African American, 3.9% Hispanics or Latinos of any race, 1.1% Asian, 0.6% American Indian and Alaska Native, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 2.0% from Some Other Race, and 1.5% from Two or More Races.[94] In 2011, 46.6% of Alabama's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[95]

The largest reported ancestry groups in Alabama are: African American (26.2%), English (23.6%), Irish (7.7%), German (5.7%), and Scots-Irish (2.0%).[96][97][98] Those citing "American" ancestry in Alabama are generally of English or British ancestry; many Anglo-Americans identify as having American ancestry because their roots have been in North America for so long, in some cases since the 1600s. Demographers estimate that a minimum of 20–23% of people in Alabama are of predominantly English ancestry and that the figure is likely higher. In the 1980 census, 41% of the people in Alabama identified as being of English ancestry, making them the largest ethnic group at the time.[99][100][101][102][103]

Based on historic migration and settlement patterns in the southern colonies and states, demographers estimated there are more people in Alabama of Scots-Irish origins than self-reported.[104] Many people in Alabama claim Irish ancestry because of the term Scots-Irish but, based on historic immigration and settlement, their ancestors were more likely Protestant Scots-Irish coming from northern Ireland, where they had been for a few generations as part of the English colonization.[105] The Scots-Irish were the largest immigrant group from the British Isles before the American Revolution, and many settled in the South, later moving into the Deep South as it was developed.

In 1984, under the Davis–Strong Act, the state legislature established the Alabama Indian Affairs Commission.[106] Native American groups within the state had increasingly been demanding recognition as ethnic groups and seeking an end to discrimination. Given the long history of slavery and associated racial segregation, the Native American peoples, who have sometimes been of mixed race, have insisted on having their cultural identification respected. In the past, their self-identification was often overlooked as the state tried to impose a binary breakdown of society into white and black.

The state has officially recognized nine American Indian tribes in the state, descended mostly from the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast. These include:[107]

- Poarch Band of Creek Indians (who also have federal recognition),

- MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians,

- Star Clan of Muscogee Creeks,

- Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama,

- Cherokee Tribe of Northeast Alabama,

- Cher-O-Creek Intra Tribal Indians,

- Ma-Chis Lower Creek Indian Tribe,

- Piqua Shawnee Tribe, and

- United Cherokee Ani-Yun-Wiya Nation.

The state government has promoted recognition of Native American contributions to the state, including the designation in 2000 for Columbus Day to be jointly celebrated as American Indian Heritage Day.[108]

Population centers

| Rank | Metropolitan Area | Population (2012 Census Estimate) |

Counties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Birmingham-Hoover | 1,136,650 | Bibb, Blount, Chilton, Jefferson, St. Clair, Shelby, Walker |

| 2 | Huntsville | 430,734 | Limestone, Madison |

| 3 | Mobile | 413,936 | Mobile |

| 4 | Montgomery | 377,149 | Autauga, Elmore, Lowndes, Montgomery |

| 5 | Tuscaloosa | 233,389 | Hale, Pickens, Tuscaloosa |

| 6 | Decatur | 154,233 | Lawrence, Morgan |

| 7 | Dothan | 147,620 | Geneva, Henry, Houston |

| 8 | Auburn-Opelika | 147,257 | Lee |

| 9 | Florence-Muscle Shoals | 146,988 | Colbert, Lauderdale |

| 10 | Anniston-Oxford-Jacksonville | 117,296 | Calhoun |

| 11 | Gadsden | 104,392 | Etowah |

| Total | 3,409,644 |

Sources: Census.gov[109]

| Rank | City | Population (2010 Census) |

County |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Birmingham | 212,237 | Jefferson |

| 2 | Montgomery | 205,764 | Montgomery |

| 3 | Mobile | 195,111 | Mobile |

| 4 | Huntsville | 183,739 | Madison Limestone |

| 5 | Tuscaloosa | 93,357 | Tuscaloosa |

| 6 | Hoover | 83,412 | Jefferson Shelby |

| 7 | Dothan | 65,496 | Houston |

| 8 | Decatur | 55,683 | Morgan Limestone |

| 9 | Auburn | 53,380 | Lee |

| 10 | Madison | 42,938 | Madison Limestone |

| 11 | Florence | 39,319 | Lauderdale |

| 12 | Gadsden | 36,856 | Etowah |

| 13 | Vestavia Hills | 34,033 | Jefferson |

| 14 | Prattville | 33,960 | Autauga |

| 15 | Phenix City | 32,822 | Russell |

Sources: Census.gov[110]

Religion

In the 2008 American Religious Identification Survey, 80% of Alabama respondents reported their religion as Christian, 6% as Catholic, and 11% as having no religion.[111] The composition of other traditions is 0.5% Mormon, 0.5% Jewish, 0.5% Muslim, 0.5% Buddhist, and 0.5% Hindu.[112]

Christianity

Alabama is located in the middle of the Bible Belt, a region of numerous Protestant Christians. Alabama has been identified as one of the most religious states in the US, with about 58% of the population attending church regularly.[113] A majority of people in the state identify as Evangelical Protestant. As of 2010, the three largest denominational groups in Alabama are the Southern Baptist Convention, The United Methodist Church, and non-denominational Evangelical Protestant.[114]

In Alabama, the Southern Baptist Convention has the highest number of adherents with 1,380,121; this is followed by the United Methodist Church with 327,734 adherents, non-denominational Evangelical Protestant with 220,938 adherents, and the Catholic Church with 150,647 adherents. Many Baptist and Methodist congregations became established in the Great Awakening of the early 19th century, when preachers proselytized across the South. The Assemblies of God had almost 60,000 members, the Churches of Christ had nearly 120,000 members. The Presbyterian churches, strongly associated with Scots-Irish immigrants of the 18th century and their descendants, had a combined membership around 60,000 (PCA-24,020, PC(USA)-36,000, plus the EPC and Associate Reformed Presbyterians).[115]

In a 2007 survey, nearly 70% of respondents could name all four of the Christian Gospels. Of those who indicated a religious preference, 59% said they possessed a "full understanding" of their faith and needed no further learning.[116] In a 2007 poll, 92% of Alabamians reported having at least some confidence in churches in the state.[117][118]

Other faiths

Although in much smaller numbers, many other religious faiths are represented in the state as well, including Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and the Bahá'í Faith.[115]

Jews have been present in what is now Alabama since 1763, during the colonial era of Mobile, when Sephardic Jews immigrated from London.[119] The oldest Jewish congregation in the state is Congregation Sha'arai Shomayim in Mobile. It was formally recognized by the state legislature on January 25, 1844.[119] Later immigrants in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries tended to be Ashkenazy Jews from eastern Europe. Jewish denominations in the state include two Orthodox, four Conservative, ten Reform, and one Humanistic synagogue.[120]

Muslims have been increasing in Alabama, with 31 mosques built by 2011, many by African-American converts.[121] Islam was a traditional religion in West Africa, from where many slaves were brought to the colonies and the United States during the centuries of the slave trade.

Several Hindu temples and cultural centers in the state have been founded by Indian immigrants and their descendants, the most well-known being the Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Birmingham, the Hindu Temple and Cultural Center Of Birmingham in Pelham, the Hindu Cultural Center of North Alabama in Capshaw, and the Hindu Mandir and Cultural Center in Tuscaloosa.[122][123]

There are six Dharma centers and organizations for Theravada Buddhists.[124] Most monastic Buddhist temples are concentrated in southern Mobile County, near Bayou La Batre. This area has attracted an influx of refugees from Cambodia, Laos, and South Vietnam during the 1970s and thereafter.[125] The four temples within a ten-mile radius of Bayou La Batre, include Chua Chanh Giac, Wat Buddharaksa, and Wat Lao Phoutthavihan.[126][127][128]

Health

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study in 2008 showed that obesity in Alabama was a problem, with most counties having over 29% of adults obese, except for ten which had a rate between 26% and 29%.[129] Residents of the state, along with those in five other states, were least likely in the nation to be physically active during leisure time.[130] Alabama, and the southeastern U.S. in general, has one of the highest incidences of adult onset diabetes in the country, exceeding 10% of adults.[131][132]

Economy

The state has invested in aerospace, education, health care, banking, and various heavy industries, including automobile manufacturing, mineral extraction, steel production and fabrication. By 2006, crop and animal production in Alabama was valued at $1.5 billion. In contrast to the primarily agricultural economy of the previous century, this was only about 1% of the state's gross domestic product. The number of private farms has declined at a steady rate since the 1960s, as land has been sold to developers, timber companies, and large farming conglomerates.[133]

Non-agricultural employment in 2008 was 121,800 in management occupations; 71,750 in business and financial operations; 36,790 in computer-related and mathematical occupation; 44,200 in architecture and engineering; 12,410 in life, physical, and social sciences; 32,260 in community and social services; 12,770 in legal occupations; 116,250 in education, training, and library services; 27,840 in art, design and media occupations; 121,110 in healthcare; 44,750 in fire fighting, law enforcement, and security; 154,040 in food preparation and serving; 76,650 in building and grounds cleaning and maintenance; 53,230 in personal care and services; 244,510 in sales; 338,760 in office and administration support; 20,510 in farming, fishing, and forestry; 120,155 in construction and mining, gas, and oil extraction; 106,280 in installation, maintenance, and repair; 224,110 in production; and 167,160 in transportation and material moving.[8]

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the 2008 total gross state product was $170 billion, or $29,411 per capita. Alabama's 2008 GDP increased 0.7% from the previous year. The single largest increase came in the area of information.[134] In 2010, per capita income for the state was $22,984.[135]

The state's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 7.2% in March 2013.[136] This compared to a nationwide seasonally adjusted rate of 7.6%.[137]

Largest employers

According to the Birmingham Business Journal, the five employers which employ the most employees in Alabama as of April 2011 were:[138]

| Employer | Number of employees |

|---|---|

| Redstone Arsenal | 25,373 |

| University of Alabama at Birmingham (includes UAB Hospital) | 18,750 |

| Maxwell Air Force Base | 12,280 |

| State of Alabama | 9,500 |

| Mobile County Public School System | 8,100 |

The next twenty largest, as identified in the Birmingham Business Journal in 2011, included:[139]

| Employer | Location |

|---|---|

| Anniston Army Depot | Anniston |

| AT&T | Multiple |

| Auburn University | Auburn |

| Baptist Medical Center South | Montgomery |

| Birmingham City Schools | Birmingham |

| City of Birmingham | Birmingham |

| DCH Health System | Tuscaloosa |

| Huntsville City Schools | Huntsville |

| Huntsville Hospital System | Huntsville |

| Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama | Montgomery |

| Infirmary Health System | Mobile |

| Jefferson County Board of Education | Birmingham |

| Marshall Space Flight Center | Huntsville |

| Mercedes-Benz U.S. International | Vance |

| Montgomery Public Schools | Montgomery |

| Regions Financial Corporation | Multiple |

| Boeing | Multiple |

| University of Alabama | Tuscaloosa |

| University of South Alabama | Mobile |

| Walmart | Multiple |

Agriculture

Alabama's agricultural outputs include poultry and eggs, cattle, fish, plant nursery items, peanuts, cotton, grains such as corn and sorghum, vegetables, milk, soybeans, and peaches. Although known as "The Cotton State", Alabama ranks between eighth and tenth in national cotton production, according to various reports,[140][141] with Texas, Georgia and Mississippi comprising the top three.

Industry

Alabama's industrial outputs include iron and steel products (including cast-iron and steel pipe); paper, lumber, and wood products; mining (mostly coal); plastic products; cars and trucks; and apparel. Also, Alabama produces aerospace and electronic products, mostly in the Huntsville area, the location of NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center and the U.S. Army Materiel Command, headquartered at Redstone Arsenal.

A great deal of Alabama's economic growth since the 1990s has been due to the state's expanding automotive manufacturing industry. Located in the state are Honda Manufacturing of Alabama, Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama, Mercedes-Benz U.S. International, and Toyota Motor Manufacturing Alabama, as well as their various suppliers. Since 1993, the automobile industry has generated more than 67,800 new jobs in the state. Alabama currently ranks 4th in the nation for vehicle exports.[142]

Automakers accounted for approximately a third of the industrial expansion in the state during 2012.[143] The eight models produced at the state's auto factories totaled combined sales of 74,335 vehicles for 2012. The strongest model sales during this period were the Hyundai Elantra compact car, the Mercedes-Benz GL-Class sport utility vehicle and the Honda Ridgeline sport utility truck.[144]

Steel producers Outokumpu, Nucor, SSAB, ThyssenKrupp, and U.S. Steel have facilities in Alabama and employ over 10,000 people. In May 2007, German steelmaker ThyssenKrupp selected Calvert in Mobile County for a 4.65 billion combined stainless and carbon steel processing facility.[145] ThyssenKrupp's stainless steel division, Inoxum, including the stainless portion of the Calvert plant, was sold to Finnish stainless steel company Outokumpu in 2012.[146] The remaining portion of the ThyssenKrupp plant had final bids submitted by ArcelorMittal and Nippon Steel for $1.6 billion in March 2013. Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional submitted a combined bid for the mill at Calvert, plus a majority stake in the ThyssenKrupp mill in Brazil, for $3.8 billion.[147]

The Hunt Refining Company, a subsidiary of Hunt Consolidated, Inc., is based in Tuscaloosa and operates a refinery there. The company also operates terminals in Mobile, Melvin, and Moundville.[148] JVC America, Inc. operates an optical disc replication and packaging plant in Tuscaloosa.[149]

Construction of an Airbus A320 family aircraft assembly plant in Mobile was formally announced by Airbus CEO Fabrice Brégier from the Mobile Convention Center on July 2, 2012. The plans include a $600 million factory at the Brookley Aeroplex for the assembly of the A319, A320 and A321 aircraft. Construction began in 2013, with plans for it to become operable by 2015 and produce up to 50 aircraft per year by 2017.[150][151] The assembly plant is the company's first factory to be built within the United States.[152] It was announced on February 1, 2013 that Airbus had hired Alabama-based Hoar Construction to oversee construction of the facility.[153]

Tourism

An estimated 20 million tourists annually visit the state. Over 100,000 of these are from other countries, including from Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan. In 2006, 22.3 million tourists spent $8.3 billion providing an estimated 162,000 jobs in the state.[154][155][156]

Healthcare

UAB Hospital is the only Level I trauma center in Alabama.[157][158] UAB is the largest state government employer in Alabama, with a workforce of about 18,000.[159]

Banking

Alabama has the headquarters of Regions Financial Corporation, BBVA Compass, Superior Bancorp and the former Colonial Bancgroup. Birmingham-based Compass Banchshares was acquired by Spanish-based BBVA in September 2007, although the headquarters of BBVA Compass remains in Birmingham. In November 2006, Regions Financial completed its merger with AmSouth Bancorporation, which was also headquartered in Birmingham. SouthTrust Corporation, another large bank headquartered in Birmingham, was acquired by Wachovia in 2004 for $14.3 billion.

The city still has major operations for Wachovia and its now post-operating bank Wells Fargo, which includes a regional headquarters, an operations center campus and a $400 million data center. Nearly a dozen smaller banks are also headquartered in the Birmingham, such as Superior Bancorp, ServisFirst and New South Federal Savings Bank. Birmingham also serves as the headquarters for several large investment management companies, including Harbert Management Corporation.

Electronics

Telecommunications provider AT&T, formerly BellSouth, also has a major presence in Alabama with several large offices in Birmingham. The company has over 6,000 employees and more than 1,200 contract employees.

Many commercial technology companies are headquartered in Huntsville, such as the network access company ADTRAN, computer graphics company Intergraph, design and manufacturer of IT infrastructure Avocent, and telecommunications provider Deltacom. Cinram manufactures and distributes 20th Century Fox DVDs and Blu-ray Discs out of their Huntsville plant.

Construction

Rust International has grown to include Brasfield & Gorrie, BE&K, Hoar Construction and B.L. Harbert International, which all routinely are included in the Engineering News-Record lists of top design, international construction, and engineering firms. (Rust International was acquired in 2000 by Washington Group International, which was in turn acquired by San-Francisco based URS Corporation in 2007.)

Law and government

State government

The foundational document for Alabama's government is the Alabama Constitution, which was ratified in 1901. At almost 800 amendments and 310,000 words, it is the world's longest constitution and is roughly forty times the length of the U.S. Constitution.[160][161] There has been a significant movement to rewrite and modernize Alabama's constitution.[162]

This movement is based upon the fact that Alabama's constitution highly centralizes power in Montgomery and leaves practically no power in local hands. Any policy changes proposed around the state must be approved by the entire Alabama legislature and, frequently, by state referendum. One criticism of the current constitution claims that its complexity and length were intentional to codify segregation and racism.

Alabama's government is divided into three equal branches: The legislative branch is the Alabama Legislature, a bicameral assembly composed of the Alabama House of Representatives, with 105 members, and the Alabama Senate, with 35 members. The Legislature is responsible for writing, debating, passing, or defeating state legislation. The Republican Party currently holds a majority in both houses of the Legislature. The Legislature has the power to override a gubernatorial veto by a simple majority (most state Legislatures require a two-thirds majority to override a veto).

The executive branch is responsible for the execution and oversight of laws. It is headed by the Governor of Alabama. Other members of executive branch include the cabinet, the Attorney General of Alabama, the Alabama Secretary of State, the Alabama State Treasurer, and the State Auditor of Alabama. The current governor of the state is Republican Robert Bentley. The lieutenant governor is Republican Kay Ivey.

The judicial branch is responsible for interpreting the Constitution and applying the law in state criminal and civil cases. The highest court is the Supreme Court of Alabama. The Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court is Republican Chuck Malone. All sitting justices on the Alabama Supreme Court are members of the Republican Party.

The members of the Legislature take office immediately after the November elections. The statewide officials, such as the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, and other constitutional offices take office in the following January.[163]

Taxes

Alabama levies a 2, 4, or 5 percent personal income tax, depending upon the amount earned and filing status. Taxpayers are allowed to deduct their federal income tax from their Alabama state tax, and can do so even if taking the standard deduction. Taxpayers who file itemized deductions are also allowed to deduct federal Social Security and Medicare taxes.

The state's general sales tax rate is 4%.[164] The collection rate could be substantially higher, depending upon additional city and county sales taxes. For example, the total sales tax rate in Mobile is 10% and there is an additional restaurant tax of 1%, which means that a diner in Mobile would pay a 11% tax on a meal. Sales and excise taxes in Alabama account for 51% of all state and local revenue, compared with an average of about 36% nationwide. Alabama is also one of the few remaining states that levies a tax on food and medicine. Alabama's income tax on poor working families is among the nation's very highest.[165] Alabama is the only state that levies income tax on a family of four with income as low as $4,600, which is barely one-quarter of the federal poverty line.[165] Alabama's threshold is the lowest among the 41 states and the District of Columbia with income taxes.[165]

The corporate income tax rate is currently 6.5%. The overall federal, state, and local tax burden in Alabama ranks the state as the second least tax-burdened state in the country.[166] Property taxes are the lowest in the U.S. The current state constitution requires a voter referendum to raise property taxes.

Since Alabama's tax structure largely depends on consumer spending, it is subject to high variable budget structure. For example, in 2003 Alabama had an annual budget deficit as high as $670 million.

Local and county government

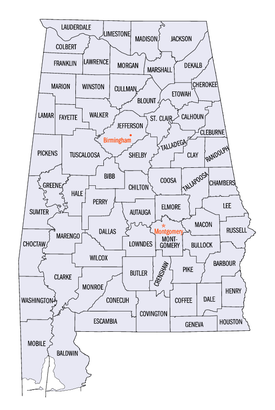

Alabama has 67 counties. Each county has its own elected legislative branch, usually called the County Commission, which usually also has executive authority in the county. Because of the restraints placed in the Alabama Constitution, all but seven counties (Jefferson, Lee, Mobile, Madison, Montgomery, Shelby, and Tuscaloosa) in the state have little to no home rule. Instead, most counties in the state must lobby the Local Legislation Committee of the state legislature to get simple local policies such as waste disposal to land use zoning.

On November 9, 2011, Jefferson County declared bankruptcy.[167][168]

Alabama is an alcoholic beverage control state; the government holds a monopoly on the sale of alcohol. However, counties can declare themselves "dry"; the state does not sell alcohol in those areas.

| Rank | County | Population (2010 Census) |

Seat | Largest city |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jefferson | 658,466 | Birmingham | Birmingham |

| 2 | Mobile | 412,992 | Mobile | Mobile |

| 3 | Madison | 334,811 | Huntsville | Huntsville |

| 4 | Montgomery | 229,363 | Montgomery | Montgomery |

| 5 | Shelby | 195,085 | Columbiana | Hoover (part) Alabaster |

| 6 | Tuscaloosa | 194,656 | Tuscaloosa | Tuscaloosa |

| 7 | Baldwin | 182,265 | Bay Minette | Daphne |

| 8 | Lee | 140,247 | Opelika | Auburn |

| 9 | Morgan | 119,490 | Decatur | Decatur |

| 10 | Calhoun | 118,572 | Anniston | Anniston |

| 11 | Etowah | 104,303 | Gadsden | Gadsden |

Politics

During Reconstruction following the American Civil War, Alabama was occupied by federal troops of the Third Military District under General John Pope. In 1874, the political coalition known as the Redeemers took control of the state government from the Republicans, in part by suppressing the African American vote.

After 1890, a coalition of White politicians passed laws to segregate and disenfranchise African American residents, a process completed in provisions of the 1901 constitution. Provisions which disfranchised African Americans also disfranchised poor Whites, however. By 1941 more Whites than African Americans had been disfranchised: 600,000 to 520,000, although the impact was greater on the African-American community, as almost all of its citizens were disfranchised and relegated to separate and unequal treatment under the law.

From 1901 through the 1960s, the state did not redraw election districts as population grew and shifted within the state. The result was a rural minority that dominated state politics until a series of court cases required redistricting in 1972.

Alabama state politics gained nationwide and international attention in the 1950s and 1960s during the American Civil Rights Movement, when racist Whites bureaucratically, and at times, violently resisted protests for electoral and social reform. Democrat George Wallace, the state's only four-term governor, was a controversial figure. Only with the passage of the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964[59] and Voting Rights Act of 1965 did African Americans regain suffrage, among other civil rights.

In 2007, the Alabama Legislature passed, and Republican Governor Bob Riley signed a resolution expressing "profound regret" over slavery and its lingering impact. In a symbolic ceremony, the bill was signed in the Alabama State Capitol, which housed Congress of the Confederate States of America.[169]

In 2010, Republicans won control of both houses of the legislature for the first time in 136 years.[170]

Elections

State elections

With the disfranchisement of African Americans, the state became part of the "Solid South", a system in which the Democratic Party became essentially the only political party in every Southern state. For nearly 100 years, local and state elections in Alabama were decided in the Democratic Party primary, with generally only token Republican challengers running in the General Election.

Republicans hold all nine seats on the Alabama Supreme Court[171] and all ten seats on the state appellate courts. Until 1994, no Republicans held any of the court seats. This change also began, likely in part, due to the same perception by voters of Democratic party efforts to disenfranchise voters again in 1994. In that general election, the then-incumbent Chief Justice of Alabama, Ernest C. Hornsby, refused to leave office after losing the election by approximately 3,000 votes to Republican Perry O. Hooper, Sr.. Hornsby sued Alabama and defiantly remained in office for nearly a year before finally giving up the seat after losing in court. This ultimately led to a collapse of support for Democrats at the ballot box in the next three or four election cycles. The Democrats lost the last of the nineteen court seats in August 2011 with the resignation of the last Democrat on the bench.

Republicans hold all seven of the statewide elected executive branch offices. Republicans hold six of the eight elected seats on the Alabama State Board of Education. In 2010, Republicans took large majorities of both chambers of the state legislature giving them control of that body for the first time in 136 years. Democrats hold one of the three seats on the Alabama Public Service Commission.[172][173][174]

Only two Republican Lieutenant Governors have been elected since Reconstruction, one is Kay Ivey, the current Lieutenant Governor.

Local elections

Many local offices (County Commissioners, Boards of Education, Tax Assessors, Tax Collectors, etc.) in the state are still held by Democrats. Local elections in most rural counties are generally decided in the Democratic primary and local elections in metropolitan and suburban counties are generally decided in the Republican Primary, although there are exceptions.[175][176]

Alabama's 67 County Sheriffs are elected in partisan races and Democrats still retain the majority of those posts. The current split is 42 Democrats, 24 Republicans, and one Independent (Choctaw).[177] However, most of the Democratic sheriffs preside over rural and less populated counties and the majority of Republican sheriffs preside over more urban/suburban and heavily populated counties.[178] Two Alabama counties (Montgomery and Calhoun) with a population of over 100,000 have Democratic sheriffs and five Alabama counties with a population of under 75,000 have Republican sheriffs (Autauga, Coffee, Dale, Coosa, and Blount).[179] As of 2012, the state of Alabama has one female sheriff, in Morgan County, Alabama, and nine African American sheriffs.[180]

Federal elections

The state's two U.S. senators are Jefferson B. Sessions III and Richard C. Shelby, both Republicans. Shelby was originally elected to the Senate as a Democrat in 1986 and re-elected in 1992, but switched parties in November 1994.

In the U.S. House of Representatives, the state is represented by seven members, six of whom are Republicans: (Jo Bonner, Mike D. Rogers, Robert Aderholt, Morris J. Brooks, Martha Roby, and Spencer Bachus) and one Democrat: Terri Sewell.

Education

Primary and secondary education

Public primary and secondary education in Alabama is under the overview of the Alabama State Board of Education as well as local oversight by 67 county school boards and 60 city boards of education. Together, 1,541 individual schools provide education for 743,364 elementary and secondary students.[181]

Public school funding is appropriated through the Alabama Legislature through the Education Trust Fund. In FY 2006–2007, Alabama appropriated $3,775,163,578 for primary and secondary education. That represented an increase of $444,736,387 over the previous fiscal year.[181] In 2007, over 82 percent of schools made adequate yearly progress (AYP) toward student proficiency under the National No Child Left Behind law, using measures determined by the state of Alabama. In 2004, 23 percent of schools met AYP.[182]

While Alabama's public education system has improved in recent decades, it lags behind in achievement compared to other states. According to U.S. Census data, Alabama's high school graduation rate—75%—is the fourth lowest in the U.S. (after Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi).[183] The largest educational gains were among people with some college education but without degrees.[184]

Colleges and universities

Alabama's programs of higher education include 14 four-year public universities, two-year community colleges, and 17 private, undergraduate and graduate universities. In the state are three medical schools (University of Alabama School of Medicine, University of South Alabama and Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine), two veterinary colleges (Auburn University and Tuskegee University), a dental school (University of Alabama School of Dentistry), an optometry college (University of Alabama at Birmingham), two pharmacy schools (Auburn University and Samford University), and five law schools (University of Alabama School of Law, Birmingham School of Law, Cumberland School of Law, Miles Law School, and the Thomas Goode Jones School of Law). Public, post-secondary education in Alabama is overseen by the Alabama Commission on Higher Education and the Alabama Department of Postsecondary Education. Colleges and universities in Alabama offer degree programs from two-year associate degrees to a multitude of doctoral level programs.[185]

The largest single campus is the University of Alabama, located in Tuscaloosa, with 33,602 enrolled for fall 2012.[186] Troy University was the largest institution in the state in 2010, with an enrollment of 29,689 students across four Alabama campuses (Troy, Dothan, Montgomery, and Phenix City), as well as sixty learning sites in seventeen other states and eleven other countries. The oldest institutions are the public University of North Alabama in Florence and the Catholic Church-affiliated Spring Hill College in Mobile, both founded in 1830.[187][188]

Accreditation of academic programs is through the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) as well as other subject-focused national and international accreditation agencies such as the Association for Biblical Higher Education (ABHE),[189] the Council on Occupational Education (COE),[190] and the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS).[191]

According to the 2011 U.S. News and World Report, Alabama had three universities ranked in the top 100 Public Schools in America (University of Alabama at 31, Auburn University at 36, and University of Alabama at Birmingham at 73).[192]

According to the 2012 U.S. News and World Report, Alabama had four tier 1 universities (University of Alabama, Auburn University, University of Alabama at Birmingham and University of Alabama in Huntsville).[193]

Sports

Teams

Alabama has several professional and semi-professional sports teams, including four minor league baseball teams.

Venues

Alabama has four of the world's largest stadiums by seating capacity: Talladega Superspeedway in Talladega, Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa, Jordan-Hare Stadium in Auburn and Legion Field in Birmingham.

The Talladega Superspeedway motorsports complex hosts a series of NASCAR events. It has a seating capacity of 143,000 and is the thirteenth largest stadium in the world and sixth largest stadium in America. Bryant-Denny Stadium serves as the home of the University of Alabama football team has a seating capacity of 101,821.[194] It is the fifth largest stadium in America and the eighth largest non-racing stadium in the world.[195] Jordan-Hare Stadium is the home field of the Auburn University football team and has a seating capacity of 87,451.[196] It is the twelfth largest college football stadium in America. Legion Field is home for the UAB Blazers football program and the Papajohns.com Bowl. It seats 80,601.[197]

Ladd-Peebles Stadium in Mobile serves as the home of the NCAA Senior Bowl, GoDaddy.com Bowl, Alabama-Mississippi All Star Classic and home of the University of South Alabama football team. Ladd-Peebles Stadium opened in 1948 and seats 40,646.[198]

In 2009, Bryant-Denny Stadium and Jordan-Hare Stadium became the homes of the Alabama High School Athletic Association state football championship games, known as the Super Six. Bryant-Denny hosts the Super Six in odd-numbered years, with Jordan-Hare taking the games in even-numbered years. Previously, the Super Six was held at Legion Field in Birmingham.[199]

Transportation

Aviation

Major airports with sustained commercial operations in Alabama include Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport (BHM), Huntsville International Airport (HSV), Dothan Regional Airport (DHN), Mobile Regional Airport (MOB), Montgomery Regional Airport (MGM), and Muscle Shoals – Northwest Alabama Regional Airport (MSL).

Rail

For rail transport, Amtrak schedules the Crescent, a daily passenger train, running from New York to New Orleans with stops at Anniston, Birmingham, and Tuscaloosa.

Roads

Alabama has five major interstate roads that cross the state: I-65 runs north–south roughly through the middle of the state; I-59/I-20 travels from the central west border to Birmingham, where I-59 continues to the north-east corner of the state and I-20 continues east towards Atlanta; I-85 originates in Montgomery and runs east-northeast to the Georgia border, providing a main thoroughfare to Atlanta; and I-10 traverses the southernmost portion of the state, running from west to east through Mobile. Another interstate road, I-22, is currently under construction. When completed around 2014 it will connect Birmingham with Memphis, Tennessee. In addition, there are currently five auxiliary interstate routes in the state: I-165 in Mobile, I-359 in Tuscaloosa, I-459 around Birmingham, I-565 in Huntsville, and I-759 in Gadsden. A sixth route, I-685, will be created when I-85 is rerouted along a new southern bypass of Montgomery. A proposed northern bypass of Birmingham will designated as I-422.

Several U.S. Highways also pass through the state, such as US 11, US 29, US 31, US 43, US 45, US 72, US 78, US 80, US 82, US 84, US 90, US 98, US 231, US 278, US 280, US 331, US 411, and US 431.

There are four toll roads in the state: Montgomery Expressway in Montgomery; Tuscaloosa Bypass in Tuscaloosa; Emerald Mountain Expressway in Wetumpka; and Beach Express in Orange Beach.

In April 2011, a study known as the American State Litter Scorecard ranked Alabama fifth (behind Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Nevada) among the "Worst" states for overall poor effectiveness and quality of its statewide public space cleanliness—primarily roadway and adjacent litter removals—from state and related efforts.[200]

Ports

The Port of Mobile, Alabama's only saltwater port, is a large seaport on the Gulf of Mexico with inland waterway access to the Midwest by way of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway. The Port of Mobile was ranked 12th by tons of traffic in the United States during 2009.[201] The newly expanded container terminal at the Port of Mobile was ranked as the 25th busiest for container traffic in the nation during 2011.[202] The state's other ports are on rivers with access to the Gulf of Mexico.

Water ports of Alabama, listed from north to south:

| Port name | Location | Connected to |

|---|---|---|

| Port of Florence | Florence/Muscle Shoals, on Pickwick Lake | Tennessee River |

| Port of Decatur | Decatur, on Wheeler Lake | Tennessee River |

| Port of Guntersville | Guntersville, on Lake Guntersville | Tennessee River |

| Port of Birmingham | Birmingham, on Black Warrior River | Tenn-Tom Waterway |

| Port of Tuscaloosa | Tuscaloosa, on Black Warrior River | Tenn-Tom Waterway |

| Port of Montgomery | Montgomery, on Woodruff Lake | Alabama River |

| Port of Mobile | Mobile, on Mobile Bay | Gulf of Mexico |

See also

- Outline of Alabama – organized list of topics about Alabama

- Index of Alabama-related articles

References

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012" (CSV). 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. December 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ The Alabama monument south of Gettysburg

- ^ "Cheehahaw". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ a b c "George Mason University, United States Election Project: Alabama Redistricting Summary. Retrieved March 10, 2008". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ a b "Alabama Occupational Projections 2008-2018" (PDF). Alabama Department of Industrial Relations. State of Alabama. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Alabama". QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 22, 2012.