United States Army Special Forces

The United States Army Special Forces (SF), colloquially known as the "Green Berets" due to their distinctive service headgear, is the special operations branch of the United States Army.[9] Although technically an Army branch, the Special Forces operates similarly to a functional area (FA), in that individuals may not join its ranks until having served in another Army branch.

The core missionset of Special Forces contains five doctrinal missions: unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, direct action, counterterrorism,[4] and special reconnaissance.[10] The unit emphasizes language, cultural, and training skills in working with foreign troops; recruits are required to learn a foreign language as part of their training and must maintain knowledge of the political, economic, and cultural complexities of the regions in which they are deployed.[11] Other Special Forces missions, known as secondary missions, include combat search and rescue (CSAR), counter-narcotics, hostage rescue, humanitarian assistance, humanitarian demining, peacekeeping, and manhunts. Other components of the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) or other U.S. government activities may also specialize in these secondary missions.[12] The Special Forces conduct these missions via five active duty groups, each with a geographic specialization; and two National Guard groups that share multiple geographic areas of responsibility.[13] Many of their operational techniques are classified, but some nonfiction works[14] and doctrinal manuals are available.[15][16][17][18]

Special Forces have a longstanding and close relationship with the Central Intelligence Agency, tracing their lineage back to the Agency's predecessors in the OSS and First Special Service Force. The Central Intelligence Agency's (CIA) highly secretive Special Activities Center, and more specifically its Special Operations Group (SOG), recruits from U.S. Army Special Forces.[19] Joint CIA–Army Special Forces operations go back to the unit MACV-SOG during the Vietnam War,[20] and were seen as recently as the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021).[21][22]

Mission

[edit]

The primary mission of the Army Special Forces is to train and lead unconventional warfare (UW) forces, or a clandestine guerrilla force in an occupied nation.[23] The 10th Special Forces Group was the first deployed SF unit, intended to train and lead UW forces behind enemy lines in the event of a Warsaw Pact invasion of Western Europe.[24] As the U.S. became involved in Southeast Asia, it was realized that specialists trained to lead guerrillas could also help defend against hostile guerrillas, so SF acquired the additional mission of Foreign Internal Defense (FID), working with Host Nation (HN) forces in a spectrum of counter-guerrilla activities from indirect support to combat command.[25]

Special Forces personnel qualify both in advanced military skills and the regional languages and cultures of defined parts of the world. While they are best known for their unconventional warfare capabilities, they also undertake other missions that include direct action raids, peace operations, counter-proliferation, counter-drug advisory roles, and other strategic missions.[26] As strategic resources, they report either to USSOCOM or to a regional Unified Combatant Command. To enhance their DA capability, specific units were created with a focus on the direct action side of special operations. First known as Commander's In-extremis Force, then Crisis Response Forces, they are now supplanted by Hard-Target Defeat companies which have been renamed Critical Threats Advisory Companies.[27][28][29][30]

SF team members work closely together and rely on one another under isolated circumstances for long periods of time, both during extended deployments and in garrison. SF non-commissioned officers (NCO) often spend their entire careers in Special Forces, rotating among assignments to detachments, higher staff billets, liaison positions, and instructor duties at the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School. With the creation of USSOCOM, SF commanders have risen to the highest ranks of U.S. Army command, including command of USSOCOM, the Army's Chief of Staff, and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[31]

History

[edit]

Between the 17th and 18th centuries, there were wars between American colonists and Native American tribes. Benjamin Church designed his force primarily to emulate Native American patterns of war. Toward this end, Church endeavored to learn to fight like Native Americans from Native Americans. He was the captain of the first Ranger force in America (1676). In 1716, his memoirs, entitled Entertaining Passages relating to Philip's War, was published and is considered by some to constitute the first American military manual and guides to unconventional warfare.[32]

Special Forces traces its roots as the Army's premier proponent of unconventional warfare and took elements from purpose-formed special operations units like the United States Army Rangers, Hunters ROTC, Alamo Scouts, First Special Service Force, and the Operational Groups of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Although the OSS was not an Army organization, many Army personnel were assigned to the OSS and later used their experiences to influence the forming of Special Forces.

During the Korean War, individuals such as former commanders Col. Wendell Fertig and Lt. Col. Russell W. Volckmann used their wartime experience to formulate the doctrine of unconventional warfare that became the cornerstone of the Special Forces.[33][34]

In 1951, Major General Robert A. McClure chose former OSS member Colonel Aaron Bank as Operations Branch Chief of the Special Operations Division of the Psychological Warfare Staff in the Pentagon.[35][36]

In June 1952, the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) was formed under Col. Aaron Bank, soon after the establishment of the Psychological Warfare School, which eventually became John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School. The 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) was split, with the cadre that kept the designation 10th SFG deployed to Bad Tölz, Germany, in September 1953. The remaining cadre at Fort Bragg (now Fort Liberty) formed the 77th Special Forces Group, which in May 1960 was reorganized and designated as today's 7th Special Forces Group.[33]

Since their establishment in 1952, Special Forces soldiers have operated in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, North Vietnam, Guatemala, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Colombia, Panama, Haiti, Somalia, Bosnia, Kosovo, 1st Gulf War, Afghanistan, Iraq, the Philippines, Syria, Yemen, Niger and, in an FID role, East Africa.[37]

The Special Forces branch was established as a basic branch of the United States Army on 9 April 1987 by Department of the Army General Order No. 35.[38]

Organizational structure

[edit]

Special Forces Groups

[edit]

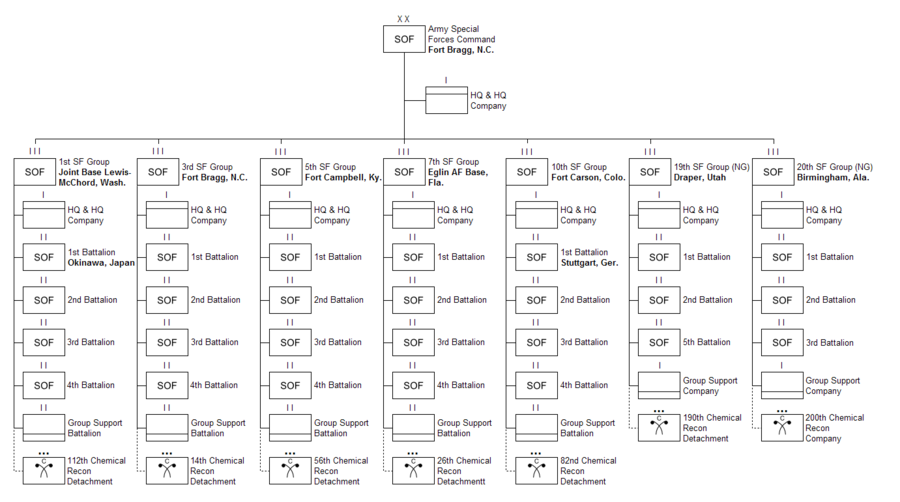

In 1957 the two original special forces groups (10th and 77th) were joined by the 1st SFG, stationed in the Far East. Additional groups were formed in 1961 and 1962 after President John F. Kennedy visited the Special Forces at Fort Bragg in 1961.[39] The 5th SFG was activated on 21 September 1961; the 8th SFG on 1 April 1963; the 6th SFG on 1 May 1963; and the 3rd SFG on 5 December 1963.[40] In addition, there have been seven Reserve groups (2nd SFG, 9th SFG, 11th SFG, 12th SFG, 13th SFG, 17th SFG, and 24th SFG) and four National Guard groups (16th SFG, 19th SFG, 20th SFG, and 21st SFG). A 4th SFG, 14th SFG, 15th SFG, 18th SFG, 22nd SFG, and 23rd SFG were in existence at some point.[41] Many of these groups were not fully staffed and most were deactivated around 1966.[49]

In the early twenty-first century, Special Forces are divided into five active duty and two Army National Guard (ARNG) Special Forces groups. Each Special Forces Group (SFG) has a specific regional focus. The Special Forces soldiers assigned to these groups receive intensive language and cultural training for countries within their regional area of responsibility.[50] Due to the increased need for Special Forces soldiers in the War on Terror, all groups—including those of the National Guard (19th and 20th SFGs)—have been deployed outside of their areas of operation, particularly to Iraq and Afghanistan. A recently released report showed Special Forces as perhaps the most deployed SOF under USSOCOM, with many soldiers, regardless of group, serving up to 75% of their careers overseas, almost all of which had been to Iraq and Afghanistan.[citation needed]

Until 2014, an SF group has consisted of three battalions, but since the Department of Defense has authorized the 1st Special Forces Command to increase its authorized strength by one third, a fourth battalion was activated in each active component group.[51]

-

Current structure of the 1st SFG (A)

-

Current structure of the 3rd SFG (A)

-

Current structure of the 5th SFG (A)

-

Current structure of the 7th SFG (A)

-

Current structure of the 10th SFG (A)

-

Current structure of the 20th SFG (A) (ARNG)

A Special Forces group is historically assigned to a Unified Combatant Command or a theater of operations. The Special Forces Operational Detachment C or C-detachment (SFODC) is responsible for a theater or a major subcomponent, which can provide command and control of up to 18 SFODAs, three SFODB, or a mixture of the two. Subordinate to it is the Special Forces Operational Detachment Bs or B-detachments (SFODB), which can provide command and control for six SFODAs. Further subordinate, the SFODAs typically raise company- to battalion-sized units when on unconventional warfare missions. They can form six-man "split A" detachments that are often used for special reconnaissance.[52]

| Beret Flash | Group |

|---|---|

| 1st Special Forces Group – Headquartered at Joint Base Lewis–McChord, Washington along with its 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Battalions, its 1st Battalion is forward deployed at Torii Station, Okinawa. The 1st SFG(A) is oriented towards the Pacific region, and is often tasked by PACOM. | |

| 3rd Special Forces Group – Headquartered at Fort Liberty, North Carolina. The 3rd SFG(A) is theoretically oriented towards all of Sub-Saharan Africa with the exception of the Eastern Horn of Africa, i.e. United States Africa Command (AFRICOM). | |

| 5th Special Forces Group – Headquartered at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. The 5th SFG(A) is oriented towards the Middle East, Persian Gulf, Central Asia and the Horn of Africa (HOA), and is frequently tasked by CENTCOM. | |

| 7th Special Forces Group – Headquartered at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. The 7th SFG(A) is oriented towards the western hemisphere: the land mass of Latin America south of Mexico, the waters adjacent to Central America and South America, the Caribbean Sea—with its 13 island nations, European and U.S. territories—the Gulf of Mexico, and a portion of the Atlantic Ocean (i.e. the USSOUTHCOM AOR and a little more). Although not aligned, the 7SFG(A) has also supported USNORTHCOM activities within the western hemisphere. | |

| 10th Special Forces Group – Headquartered at Fort Carson, Colorado along with its 2nd, 3rd and newly added 4th Battalions, its 1st Battalion is forward deployed in the Panzer Kaserne (Panzer Barracks) in Böblingen near Stuttgart, Germany. The 10th SFG(A) is theoretically oriented towards Europe, mainly Central and Eastern Europe, the Balkans, Turkey, Israel, Lebanon, and Northern Africa, i.e. EUCOM. | |

| 19th Special Forces Group – One of two National Guard Special Forces Groups. Headquartered in Draper, Utah, with companies in Washington, West Virginia, Ohio, Rhode Island, Colorado, California, and Texas, the 19th SFG(A) is oriented towards Southwest Asia (shared with 5th SFG(A)), Europe (shared with 10th SFG(A)), as well as Southeast Asia (shared with 1st SFG(A)). | |

| 20th Special Forces Group – One of two National Guard Special Forces Groups. Headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama, with battalions in Alabama (1st Battalion), Mississippi (2nd Battalion), and Florida (3rd Battalion), with assigned Companies and Detachments in North Carolina; Chicago, Illinois; Louisville, Kentucky; Western Massachusetts; and Baltimore, Maryland. The 20th SFG(A) has an area of responsibility (AOR) covering 32 countries, including Latin America south of Mexico, the waters, territories, and nations in the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the southwestern Atlantic Ocean. Orientation towards the region is shared with 7th SFG(A). | |

| Inactive Groups | |

| 6th Special Forces Group – Active from 1963 to 1971. Based at Fort Bragg, North Carolina (renamed Fort Liberty in 2023). Assigned to Southwest Asia (Iraq, Iran, etc.) and Southeast Asia. Many of the 103 original Son tay raider volunteers were from 6SFGA. | |

| 8th Special Forces Group – Active from 1963 to 1972. Responsible for training armies of Latin America in counterinsurgency tactics. | |

| 11th Special Forces Group (U.S. Army Reserve) – Active from 1961 to 1994. | |

| 12th Special Forces Group (U.S. Army Reserve) – Active from 1961 to 1994. |

Battalion Headquarters Element – SF Operational Detachment-C (SFODC) composition

[edit]The SFODC, or "C-Team", is the headquarters element of a Special Forces battalion. As such, it is a command and control unit with operations, training, signals, and logistic support responsibilities to its three subordinate line companies. A lieutenant colonel commands the battalion as well as the C-Team, and the Battalion Command Sergeant Major is the senior NCO of the battalion and the C-Team. There are an additional 20–30 SF personnel who fill key positions in operations, logistics, intelligence, communications, and medical. A Special Forces battalion usually consists of four companies: "A", "B", "C", and Headquarters/Support.[53][54]

Company Headquarters Element – SF Operational Detachment-B (SFODB) composition

[edit]

The ODB, or "B-Team", is the headquarters element of a Special Forces company, and it is usually composed of 11–13 soldiers. While the A-team typically conducts direct operations, the purpose of the B-Team is to support the company's A-Teams both in garrison and in the field.[citation needed] The B-Teams are numbered similarly to A-Teams (see below), but the fourth number in the sequence is a 0. For example, ODB 5210 would be 5th Special Forces Group, 2nd Battalion, A Company's ODB.[54]

The ODB is led by an 18A, usually a major, who is the company commander (CO). The CO is assisted by his company executive officer (XO), another 18A, usually a captain. The XO is himself assisted by a company technician, a 180A, generally, a chief warrant officer three, who assists in the direction of the organization, training, intelligence, counter-intelligence, and operations for the company and its detachments. The company commander is assisted by a senior non-commissioned officer, an 18Z, usually a sergeant major. A second 18Z acts as the operations sergeant, usually a master sergeant, who assists the XO and technician in their operational duties. He has an 18F assistant operations sergeant, who is usually a sergeant first class. The company's support comes from an 18D medical sergeant, usually a sergeant first class, and two 18E communications sergeants, usually a sergeant first class and a staff sergeant.[52]

Support positions as part of the ODB/B Team within an SF Company are as follows:

- The supply NCO, usually a Staff Sergeant, the commander's principal logistical planner, works with the battalion S-4 to supply the company.

- The Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear (CBRN defense) NCO, usually a Sergeant, maintains and operates the company's NBC detection and decontamination equipment, and assists in administering NBC defensive measures.

- Other jobs can also exist depending on the B-Team structure. Specialist team members can include I.T. (S-6) personnel, and Military Intelligence Soldiers, including Intelligence Analysts (35F), Human Intelligence Collectors (35M), Signals Intelligence (35 N/P - also known as SOT-A and SOT-B as related to their positions on SFODA and SFODB teams), Intelligence Officers (35 D/E/F), and Counterintelligence Special Agents (35L/351L).

Basic Element – SF Operational Detachment-A (SFODA) composition

[edit]A Special Forces company normally consists of six Operational Detachments-A (ODA or "A-Teams").[55][56] Each ODA specializes in an infiltration skill or a particular mission-set (e.g. military free fall (HALO), combat diving, mountain warfare, maritime operations, etc.). Each ODA Team's number is unique. Prior to 2007, number typically consisted of three digits reflecting the Group, the specific ODB within the battalion, and the specific ODA within the company.[54] Starting in 2007, though, the number sequence was changed to a four-digit format. The first digit would specify group (1=1st SFG, 3=3rd SFG, 5=5th SF, 7=7th SFG, 0=10th SFG, 9=19th SFG, 2=20th SFG). The second digit would be 1-4 for 1st through 4th Battalion. The third digit would be 1-3 for A to C Companies. The fourth digit would be 1-6 for the particular team within that company. For example, ODA 1234 would signify the fourth ODA in Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Special Forces Group.[54]

An ODA consists of 12 soldiers, each of whom has a specific function (MOS or Military Occupational Specialty) on the team; however, all members of an ODA conduct cross-training. The ODA is led by an 18A (Detachment Commander), a captain, and a 180A (Assistant Detachment Commander) who is their second in command, usually a Warrant Officer One or Chief Warrant Officer Two. The team also includes the following enlisted soldiers: one 18Z (Operations Sergeant) (known as the "Team Sergeant"), usually a Master Sergeant, one 18F (Assistant Operations and Intelligence Sergeant), usually a Sergeant First Class, and two each, 18Bs (Weapons Sergeant), 18Cs (Engineer Sergeant), 18Ds (Medical Sergeant), and 18Es (Communications Sergeant), usually Sergeants First Class, Staff Sergeants, or Sergeants. This organization facilitates 6-man "split team" operations, redundancy, and mentoring between a senior NCO and their junior assistant.[citation needed]

Qualifications

[edit]

The basic eligibility requirements to be considered for entry into the Special Forces for existing service members are:

- Be age 20–36[57][58]

- Be a U.S. citizen[57]

- Be a high school graduate[57]

- Have Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) placement test GT score of 110 or above[57]

- Be qualified for Airborne School or Ranger School[57]

- Pass the Physical Fitness test and meet height and weight standards[57]

- Be of rank E-3 (Private First Class, Specialist, Corporal, Sergeant, or staff sergeant) or higher[57]

- Have fewer than 9 months time in grade as E-7 when applying[57]

- Have no more than 12-14 years in service prior to training and have 36 months or more left in service after completing SF training (if able to)[57]

- Be eligible for secret clearance[57]

For officers, the requirements are:

- Be of rank first lieutenant or captain[57]

- Have a Defense Language Aptitude Battery score of 85 or higher[57]

- Be eligible for top secret clearance[57]

- Support personnel assigned to a Special Forces unit who do not possess a Special Forces 18-series career management field (CMF) MOS are not "Special Forces qualified", as they have not completed the Special Forces Qualification Course (SFQC or "Q" Course); however, they do have the potential to be awarded the Special Qualification Identifier (SQI) "S" (Special Operations / Special Operations Support) once they complete the appropriate unit-level training, 24 months with their Special Forces unit, and Basic Airborne School (except for CMF 15).[59]

Selection and training

[edit]The Special Forces soldier trains on a regular basis over the course of their entire career. The initial formal training program for entry into Special Forces is divided into four phases collectively known as the Special Forces Qualification Course or, informally, the "Q Course". The length of the Q Course changes depending on the applicant's primary job field within Special Forces and their assigned foreign language capability, but will usually last between 55 and 95 weeks. After successfully completing the Special Forces Qualification Course, Special Forces soldiers are then eligible for many advanced skills courses. These include, but are not limited to, the Military Free Fall Parachutist Course, the Combat Diver Qualification Course, the Special Operations Combat Medic Course,[60] the Special Forces Sniper Course,[61] among others.[18]

Women in the Green Berets

[edit]In 1981 Capt. Kathleen Wilder became the first woman to qualify for the Green Berets. She was told she had failed a field exercise just before graduation, but she filed a sex discrimination complaint, and it was determined that she "had been wrongly denied graduation." Wilder, a former military intelligence officer, was ultimately allowed to wear the Special Forces Tab when it was created in 1983, and continued to do so over her 28-year career until she retired as a lieutenant colonel. Army Times reported that in July 2020, the first woman to complete the Army Special Forces Qualification Course graduated and moved on to a Green Beret team.[62][63][64][65][66][67]

Special Forces MOS descriptions

[edit]- 18A – Special Forces Officer[68]

- 180A – Special Forces Warrant Officer[69]

- 18B – Special Forces Weapons Sergeant[70]

- 18C – Special Forces Engineer Sergeant[71]

- 18D – Special Forces Medical Sergeant[72]

- 18E – Special Forces Communications Sergeant[73]

- 18F – Special Forces Intelligence Sergeant[74]

- 18X – Special Forces Candidate (Active Duty and National Guard Enlistment Option)[75]

- 18Z – Special Forces Operations Sergeant[76]

Uniforms and insignia

[edit]Green beret

[edit]

U.S. Army Special Forces adopted the green beret unofficially in 1954 after searching for headgear that would set them visually apart. Members of the 77th SFG began searching through their accumulated berets and settled on the rifle green color from Captain Miguel de la Peña's collection; since 1942 the British Commandos had permeated the use of green on berets of specialist forces, and many current international military organisations followed this practice. Captain Frank Dallas had the new beret designed and produced in small numbers for the members of the 10th & 77th Special Forces Groups.[77]

Their new headdress was first worn at a retirement parade at Fort Bragg (now Fort Liberty) on 12 June 1955 for Major General Joseph P. Cleland, the now-former commander of the XVIII Airborne Corps. Onlookers thought that the operators were a foreign delegation from NATO. In 1956 General Paul D. Adams, the post commander at Fort Bragg, banned the wearing of the distinctive headdress,[78] although members of the Special Forces continued to wear it surreptitiously.[79] This was reversed on 25 September 1961 by Department of the Army Message 578636, which designated the green beret as the exclusive headdress of the Army Special Forces.[80]

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy authorized them for use exclusively by the U.S. Special Forces. Preparing for a 12 October visit to the Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the president sent word to the center's commander, Colonel William P. Yarborough, for all Special Forces soldiers to wear green berets as part of the event. The president felt that since they had a special mission, Special Forces should have something to set them apart from the rest. In 1962, he called the green beret "a symbol of excellence, a badge of courage, a mark of distinction in the fight for freedom."[77]

Forrest Lindley, a writer for the newspaper Stars and Stripes who served with Special Forces in Vietnam said of Kennedy's authorization: "It was President Kennedy who was responsible for the rebuilding of the Special Forces and giving us back our Green Beret. People were sneaking around wearing [them] when conventional forces weren't in the area and it was sort of a cat and mouse game. Then Kennedy authorized the Green Beret as a mark of distinction, everybody had to scramble around to find berets that were really green. We were bringing them down from Canada. Some were handmade, with the dye coming out in the rain."[81]

Kennedy's actions created a special bond with the Special Forces, with specific traditions carried out since his funeral when a sergeant in charge of a detail of Special Forces soldiers guarding the grave placed his beret on the coffin.[81] The moment was repeated at a commemoration of the 25th anniversary of JFK's death – General Michael D. Healy (ret.), the last commander of Special Forces in Vietnam and later a commander of the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School, spoke at Arlington National Cemetery, after which a wreath in the form of a green beret was placed on Kennedy's grave.[81]

Distinctive unit insignia

[edit]

A silver colored metal and enamel device 1+1⁄8 inches (2.9 cm) in height consisting of a pair of silver arrows in saltire, points up and is surmounted at their junction by the V-42 stiletto silver dagger with black handle point up; all over and between a black motto scroll arcing to the base and inscribed "DE OPPRESSO LIBER" in silver letters.[82]

The insignia is the crossed arrow collar insignia (insignia of the branch) of the First Special Service Force, World War II combined with the fighting knife which is of a distinctive shape and pattern only issued to the First Special Service Force. The motto is translated as "From Oppression We Will Liberate Them."[82]

The distinctive unit insignia was approved on 8 July 1960. The insignia of the 1st Special Forces was authorized to be worn by personnel of the U.S. Army Special Forces Command (Airborne) and its subordinate units on 7 March 1991. The wear of the insignia by the U.S. Army Special Forces Command (Airborne) and its subordinate units was canceled and it was authorized to be worn by personnel of the 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) and their subordinate units which were not authorized a distinctive unit insignia in their own right and amended to change the symbolism on 27 October 2016.[82]

Shoulder sleeve insignia

[edit]The shoulder sleeve insignia (SSI) of the 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) is worn by all those assigned to the command and its subordinate units who have not been authorized their own SSI, such as the Special Forces Groups. According to the U.S. Army Institute of Heraldry, the shape and items depicted in the SSI have special meaning: "The arrowhead alludes to the American Indian's basic skills in which Special Forces personnel are trained to a high degree. The dagger represents the unconventional nature of Special Forces operations, and the three lightning flashes, their ability to strike rapidly by Sea, Air or Land." Army Special Forces were the first Special Operations unit to employ the "sea, air, land" concept nearly a decade before units like the Navy SEALs were created.[83]

Before the 1st Special Forces Command SSI was established, the special forces groups that stood up between 1952 and 1955 wore the Airborne Command SSI. According to the U.S. Army Institute of Heraldry, the Airborne Command SSI was reinstated on 10 April 1952—after being disbanded in 1947—and authorized for wear by certain classified units[84]—such as the newly formed 10th and 77th Special Forces Groups—until the 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) SSI was established on 22 August 1955.[83]

Special Forces Tab

[edit]

Introduced in June 1983, the Special Forces Tab is a service school qualification tab awarded to soldiers who complete one of the Special Forces Qualification Courses. Unlike the Green Beret, soldiers who are awarded the Special Forces Tab are authorized to wear it for the remainder of their military careers, even when not serving with an Army Special Forces unit. The cloth tab is a teal blue colored arc tab 3+1⁄4 inches (8.3 cm) in length and 11⁄16 inch (1.7 cm) in height overall, the designation "SPECIAL FORCES" in gold-yellow letters 5⁄16 inch (0.79 cm) in height and is worn on the left sleeve of utility uniforms above a unit's Shoulder Sleeve Insignia and below the President's Hundred Tab (if so awarded). The metal Special Forces Tab replica comes in two sizes, full and dress miniature. The full size version measures 5⁄8 inch (1.6 cm) in height and 1+9⁄16 inches (4.0 cm) in width. The miniature version measures 1⁄4 inch (0.64 cm) in height and 1 inch (2.5 cm) in width. Both are teal blue with yellow border trim and letters and are worn above or below ribbons or medals on the Army Service Uniform.[85][86][87]

- 1) Basic Eligibility Criteria. Any person meeting one of the criteria below may be awarded the Special Forces (SF) tab:

- 1.1) Successful completion of U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School (USAJFKSWCS) approved Active Army (AA) institutional training leading to SF qualification.

- 1.2) Successful completion of a USAJFKSWCS approved Reserve Component (RC) SF qualification program.

- 1.3) Successful completion of an authorized unit administered SF qualification program.

- 2) Active Component institutional training. The SF Tab may be awarded to all personnel who meet the following:

- 2.1) For successful completion of the Special Forces Qualification Course or Special Forces Detachment Officer Qualification Course (previously known as the Special Forces Officer Course). These courses are/were conducted by the USAJFKSWC (previously known as the U.S. Army Institute for Military Assistance).

- 2.2) Before 1 January 1988, for successful completion of the then approved program of instruction for Special Forces qualification in a Special Forces Group, who were subsequently awarded, by a competent authority, SQI "S" in Career Management Field 18 (enlisted), or SQI "3" in Functional Area 18 (officer).

- 3) Reserve Component (RC) SF qualification programs. The SF Tab may be awarded to all personnel who successfully complete an RC SF qualification program according to TRADOC Regulation 135–5, dated 1 June 1988 or its predecessors and who were subsequently awarded, by a competent authority, SQI "S" or "3" in MOS 11B, 11C, 12B, 05B, 91B, or ASI "5G" or "3." The USAJFKSWCS will determine individual entitlement for an award of the SF Tab based on historical review of Army, Continental Army Command (CONARC), and TRADOC regulations prescribing SF qualification requirements in effect at the time the individual began an RC SF qualification program.

- 4) Unit administered SF qualification programs. The SF Tab may be awarded to all personnel who successfully completed unit administered SF qualification programs as authorized by regulation. The USAJFKSWCS will determine individual entitlement to an award of the SF Tab based upon a historical review of regulations prescribing SF qualification requirements in effect at the time the individual began a unit administered SF qualification program.

- 5) Former wartime service. The Special Forces Tab may be awarded retroactively to all personnel who performed the following wartime service:

- 5.1) 1942 through 1973. Served with a Special Forces unit during wartime and were either unable to or not required to attend a formal program of instruction but were awarded SQI "S", "3", "5G" by the competent authority.

- 5.2) Before 1954. Service for at least 120 consecutive days in one of the following organizations:

- 5.2.1) 1st Special Service Force, August 1942 to December 1944.

- 5.2.2) OSS Detachment 101, April 1942 to September 1945.

- 5.2.3) OSS Jedburgh Detachments, May 1944 to May 1945.

- 5.2.4) OSS Operational Groups, May 1944 to May 1945.

- 5.2.5) OSS Maritime Unit, April 1942 to September 1945.

- 5.2.6) 6th Army Special Reconnaissance Unit (Alamo Scouts), February 1944 to September 1945.

- 5.2.7) 8240th Army Unit, June 1950 to July 1953.

- 5.2.8) 1954 through 1975. Any company grade officer or enlisted member awarded the CIB or CMB while serving for at least 120 consecutive days in one of the following type organizations:

- 5.2.8a) SF Operational Detachment-A (A-Team).

- 5.2.8b) Mobile Strike Force.

- 5.2.8c) SF Reconnaissance Team.

- 5.2.8d) SF Special Project Unit.

Camouflage pattern

[edit]During the Vietnam War, the Green Berets of the 5th Special Forces Group wanted camouflage clothing to be made in Tigerstripe. So they contracted with Vietnamese and other Southeast Asian producers to make fatigues and other items such as boonie hats using tigerstripe fabric. When Tigerstripes made a comeback in the 21st century, they were used by Green Berets for OPFOR drills.

From 1981 to the mid-2000s, they had worn the Battle Dress Uniform.

Since the War on Terror, they have worn Universal Camouflage Pattern but phased that out in favor of MultiCam and Operational Camouflage Pattern (OCP) uniforms.

Yarborough knife

[edit]This knife was designed and built by Bill Harsey Jr. in collaboration with Chris Reeve Knives. Starting in 2002, all graduates of the qualification course were awarded a Yarborough knife, designed by Bill Harsey and named after Lt. Gen. William Yarborough, considered the father of the modern Special Forces. All knives awarded are individually serial-numbered, and all awardees' names are recorded in a special logbook.[88]

Vehicles

[edit]

During the Green Berets' missions in other nations, they would use Ground Mobility Vehicle (GMV)-S Humvees made by AM General for various uses. While using purpose built technicals for patrol on rugged terrain which would help preserve the clandestine nature of their missions. They have also had access to the General Dynamics M1288 GMV 1.1 variant of the Army Ground Mobility Vehicle as well as the Oshkosh M-ATV Special Forces variant MRAPs.

For aircraft other than the ones used by the US military and its special forces/special operations forces units, they extensively used the CIA-operated Mi-8 and Mi-17 variants of those military helicopters in Afghanistan during the initial stages of Operation Enduring Freedom.[89]

Use of the term "Special Forces"

[edit]In countries other than the U.S., the term "special forces" or "special operations forces" (SOF) is often used generically to refer to any units with elite training and special mission sets. In the U.S. military, "Special Forces" is a proper (capitalized) noun referring exclusively to U.S. Army Special Forces (a.k.a. "The Green Berets").[55] The media and popular culture frequently misapply the term to Navy SEALs and other members of the U.S. Special Operations Forces.[90] As a result, the terms USSF and, less commonly, USASF have been used to specify United States Army Special Forces.[91][92][93]

Use of the term "Operator"

[edit]

The term "Operator" pre-dates American Special Operations and can be found in books referring to French Special Operations as far back as WWII. Examples include A Savage War of Peace[94] by Alistair Horne and The Centurions[95] by Jean Larteguy.

The origin of the term operator in American special operations comes from the U.S. Army Special Forces (referred to by many civilians as "Green Berets"). The Army Special Forces were established in 1952, ten years before the Navy SEALs, and 25 years before Delta Force. Every other modern U.S. special operations unit in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines was established after 1977. In Veritas: Journal of Army Special Operations History, Charles H. Briscoe states that the Army "Special Forces did not misappropriate the appellation. Unbeknownst to most members of the Army Special Operations Force community, that moniker was adopted by the Special Forces in the mid-1950s." He goes on to state that all qualified enlisted and officers in Special Forces had to "voluntarily subscribe to the provisions of the 'Code of the Special Forces Operator' and pledge themselves to its tenets by witnessed signature." This pre-dates every other special operations unit that currently uses the term/title operator.[96]

Inside the United States Special Operations community, an operator is a Delta Force member who has completed selection and has graduated the Operators Training Course.[citation needed] Operator was used by Delta Force to distinguish between operational and non-operational personnel assigned to the unit.[21]: 325 Other special operations forces use specific names for their jobs, such as Army Rangers and Air Force Pararescuemen. The Navy uses the acronym SEAL for both their special warfare teams and their individual members, who are also known as Special Operators. In 2006 the Navy created "Special Warfare Operator" as a rating specific to Naval Special Warfare enlisted personnel, grades E-4 to E-9 (see Navy special warfare ratings).[97] Operator is the specific term for operational personnel, and has become a colloquial term for almost all special operations forces in the U.S. military, as well as around the world.[96]

In popular culture

[edit]See also

[edit]- 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (Delta Force)

- Alamo Scouts

- Blue Light

- Central Intelligence Agency's Special Activities Center

- Devil's Brigade

- Dogs in warfare - There was an SF Multi-Purpose canine team providing security for a nearby mortar position during the Syrian Civil War's Deir ez-Zor campaign in Syria, October 11, 2018.

- Green Light Teams

- Intelligence Support Activity

- Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group

- Phoenix Program

- Recondo

- Unconventional warfare (United States)

- United States Army Counterintelligence

Similar Units

[edit]- Ranger Regiment (United Kingdom) - British Special Operations Capable unit with similar roles

- Canadian Special Operations Regiment - Canadian special forces unit with similar roles

- 2nd Commando Regiment - Australian special forces unit with similar roles

- JW Komandosow - Polish special forces unit with similar roles

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Venhuizen, Harm (14 July 2020). "How the Green Berets got their name". Army Times. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ "History of the Special Forces". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Army Birthdays: Branch Birthdays". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.; "General Orders No. 35: Army Special Forces Branch" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Headquarters Department of the Army. 19 June 1987. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ a b

- "Army Special Forces: Mission and History". military.com. 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- "Special Forces Officer". goarmy.com. 16 April 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- "THE UNITED STATES ARMY SPECIAL FORCES". greenberetfoundation.org. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- "ASSESSING U.S. SPECIAL OPERATIONS COMMAND'S MISSIONS AND ROLES". govinfo.gov. 29 June 2006. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ Stanton, Doug (24 June 2009). "The Quiet Professionals: The Untold Story of U.S. Special Forces in Afghanistan". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012.

- ^ Gentile, Carmen (9 November 2011). "In Afghanistan, special units do the dirty work". USA Today. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011.

- ^ William Bishop, Mac (6 March 2017). "Inside the Green Berets' Hunt for Wanted Warlord Joseph Kony". NBC News. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022.

- ^ Robles, Nelson (29 March 2017). "Special Operations Troops From 15 Countries Conduct Allied Spirit VI". Department of Defence. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022.

- ^ Goldberg, Maren (n.d.). "Green Berets: United States military". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ ""Special Forces Core Missions - Army National Guard"".

- ^ Lee, Michael (24 March 2022). "The US Army's Green Berets quietly helped tilt the battlefield a little bit more toward Ukraine". MSN. FOX News. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Joint Chiefs of Staff (17 December 2003). "Joint Publication 3-05: Doctrine for Joint Special Operations" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2000. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ "USASOC Headquarters Fact Sheet". United States Army Special Operations Command. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Waller, Douglas C. (1995). The Commandos: The Inside Story of America's Secret Soldiers. New York: Dell Publishing. ISBN 978-0440220466. OCLC 32941898.

- ^ FM 3-05: Army Special Operations Forces (PDF). U.S. Department of the Army. September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2022.

- ^ "FM 3-05.102 Army Special Forces Intelligence" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Department of the Army. July 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2022.

- ^ "Joint Publication 3-05.5: Special Operations Targeting and Mission Planning Procedures" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center. Joint Chiefs of Staff. 1993. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2000. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- ^ a b "Interview U.S. Army General Tommy Franks". Campaign Against Terror. Frontline. PBS. 8 September 2002. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022.

- ^ Waller, Douglas (3 February 2003). "The CIA's Secret Army". Time. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007.

- ^ Plaster, John L. (1998). SOG: The Secret Wars of America's Commandos in Vietnam. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0451195081. OCLC 39543945.

- ^ a b Haney, Eric L. (2002). Inside Delta Force. New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0385336031. OCLC 57373772.

- ^ Pelley, Scott (2 October 2008). "Elite Officer Recalls Bin Laden Hunt". 60 Minutes. CBS News. Archived.

- ^ "Primary Special Forces Missions". Go Army. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ "10th SFG (A) History". United States Army Special Operations Command. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022.

- ^ Wertz, Anthony; Gallagher, Stuart (18 April 2021). "Rethinking Army Special Operation Forces-Department of State Partnership in Europe | Small Wars Journal". Small Wars Journal. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021.

- ^ Maurer, Kevin (2013). Gentlemen Bastards: On the Ground in Afghanistan with America's Elite Special Forces. New York: Berkley Books. p. 15. ISBN 9780425252697.

- ^ Scarborough, Rowan (23 January 2013). "Africa's Fast-Reaction Force Ready to Go from Colorado". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ Trevithick, Joseph (2 December 2020). "The Army is Training Specialized Companies of Green Berets to Crack Hard Targets". The WarZone. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Atlamazoglou, Stavros (4 March 2020). "The Army 1st Special Forces Command disbands elite Crisis Response Forces". SOFREP. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022.

- ^ "Shadows in the night; Polish, German SOF train with U.S. Special Forces". army.mil. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Hugh Shelton". Hugh Shelton. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022.

- ^ Grenier, John (2005). The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607–1814. Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1-139-44470-5.

- ^ a b "U.S. Army Special Forces Command (Airborne) History". U S ARMY SPECIAL OPERATIONS COMMAND. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Volckmann, Russell W. (October 1951). "FM 31-21 GUERRILLA WARFARE AND SPECIAL FORCES OPERATIONS" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2014. Alt URL

- ^ Officer Efficiency Report, Bank, Aaron, 11 May 1952, Aaron Bank Service Record, National Military Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri

- ^ "Col Aaron Bank: Commander, 10th Special Forces Group (1902-1944)". U.S. Army Special Operations Command History Office. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Army Special Operations Forces Timeline". U.S.Army Special Operations Command History Office. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Army General Order No. 35" (PDF). US Army Center of Military History. 19 June 1987. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Tsouras 1994, p. 91.

- ^ a b Mahon, John K; Danysh, Romana (1972). Army lineage series Infantry Part I: Regular Army. Washington D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army. pp. 887–922. LCCN 74-610219. OCLC 557542564. Government Publishing Office Stock Number 0829-0082. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Mahon & Romana 1972, p. 889.

- ^ Peters, John E.; Shannon, Brian; Boyer, Matthew E. (2012). National Guard Special Forces Enhancing the Contributions of Reserve Component Army Special Operations Forces (PDF). RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-6012-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Reserve Component Special Forces Groups - (RC SF)". Special Forces History. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "17th Special Forces Group". Special Forces History. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Army Public Affairs Office Records GOGA 35330" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2022.

- ^ Dietrich, Joseph K. (March 1992). "Ensuring Readiness for Active and Reserve Component SF Units" (PDF). Special Warfare. Vol. 5, no. 1. PB 80–92–1.

- ^ "Report to the Chairman, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives: Special Operations Forces Force Structure and Readiness Issues" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. March 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Morgan, Wayne (15 April 1991). "Reserve Component Special Forces Integration and Employment Models for the Operational Continuum" (PDF). United States Army War College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ [40][42][43][44][45][46][47][48]

- ^ "United States Army Special Forces Command". United States Army Special Operations Command. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022.

- ^ "ARSOF 2022 Part II" (PDF). Special Warfare. 27 (3): 6. July–September 2014. ISSN 1058-0123. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Structure". Fort Campbell. United States Army. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ Fox, David (8 September 2002). "Frontline: Campaign Against Terror" (Interview). PBS Frontline. Archived from the original on 27 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Piasecki, Eugene G. (2009). ""The A Team Numbering System"". U.S. Army Special Operations Command History Office. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ a b USASOC (26 October 2009). "Special Forces - Shooters and thinkers". Army.mil. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha (SFOD A)". American Special Ops. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "SPECIAL FORCES REQUIREMENTS". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "SF Qualifications". GoArmySOF. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "Section IV. Chapter 12. Special Qualification Identifiers and Additional Skill Identifiers" (PDF). army.mil. 9 June 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "SOCM Course | Hurley Medical Center". www.hurleymc.com. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Special Forces Sniper Course (SFSC)". specialforcestraining.info. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Gibbons-Neff, Thomas (25 February 2020). "First Woman Set to Pass Special Forces Training and Join Green Berets". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 December 2023 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Andrew, Scottie (10 July 2020). "A woman soldier is joining the Green Berets -- a first for the Army Special Forces unit". CNN. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Rempfer, Kyle (10 July 2020). "New female Green Beret is a huge milestone, but she isn't the first to earn the title". Army Times. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Ismay, John (28 February 2020). "The True Story of the First Woman to Finish Special Forces Training". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 December 2023 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "First female Green Beret graduates Army Special Forces course". UPI. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Britzky, Haley (25 February 2020). "A woman is about to finish Green Beret training for the first time in history". Task & Purpose. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Special Forces Officer (18A)". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Warrant Officer Prerequisites and Duty Description 180A - Special Forces Warrant Officer". US Army Recruiting Command. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009.

- ^ "Special Forces Weapons Sergeant (18B)". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Special Forces Engineer Sergeant (18C)". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Special Forces Medical Sergeant (18D)". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Special Forces Communications Sergeant (18E)". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022.

- ^ "Special Forces Assistant Operations and Intelligence Sergeant (18F)". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022.

- ^ "Special Forces Candidate Jobs (18X)". GoArmy. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022.

- ^ "18Z - Special Forces Operations Sergeant MOS". cool.osd.mil.

- ^ a b "History: Special Forces Green Beret". Special Forces Association HQ. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ Simpson, Charles M. III (1983). Inside the Green Berets: The First Thirty Years: A History of the U.S. Army Special Forces. Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780891411635. OCLC 635308594.

- ^ Brown, Jerold E., ed. (2001). "Green Beret". Historical Dictionary of the United States Army (Illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 220. ISBN 9780313293221.

- ^ "Army Black Beret A Short History of the Use of Berets in the U.S. Army". Army.mil. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Gamarekian, Barbara (22 November 1988). "Washington Talk: John F. Kennedy, 1917–1963; Hundreds Are in Capital for 25th Remembrance". The New York Times. p. 2. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "1st Special Forces, Distinctive Unit Insignia". United States Army Institute of Heraldry. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "U.S. ARMY SPECIAL FORCES GROUP (AIRBORNE)". United States Army Institute of Heraldry. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016.

- ^ "AIRBORNE COMMAND". United States Army Institute of Heraldry. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Special Forces Tab". United States Army Institute of Heraldry. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020.

- ^ a b "U.S. Army Regulation 600–8–22: Personnel-General: Military Awards" (PDF). Official Department of the Army Publications and Forms. 11 December 2006. pp. 117–118. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Army Pamphlet 670-1: Uniform and Insignia, Guide to the Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia" (PDF). Official Department of the Army Publications and Forms. 31 March 2014. pp. 6, 201, 244–245, 252, 256, 258–260. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Balestrieri, Steve (7 April 2021). "THE YARBOROUGH KNIFE, A TRIBUTE TO THE MAN WHO SHAPED THE GREEN BERETS". SOFREP. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "CIA's Mi-17 Helicopter Comes Home". Soldier Systems Daily. 29 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Here's the difference between special ops and special forces". We Are The Mighty. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 28 July 2021.

- ^ Shrout, Brian S.; Sampson, Ronald N.; Patton, Jerry D.; Jones, Duwayne (4 November 2007). "United States Army Special Forces Unit of Command". Defense Technical Information Center. United States Army Sergeants Major Academy. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Morelli, Justin P. (31 December 2021). "Special Forces Training [Image 4 of 14]". DVIDS. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Kelly, Francis J. (1973). "Vietnam Studies U.S. Army Special Forces 1961-1971" (PDF). US Army Center of Military History. Department of the Army. p. 218. CMH Pub 90-23-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Horne, Alistair (1978). A Savage War of Peace : Algeria, 1954-1962. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-61964-1.

- ^ Lartéguy, Jean (2015) [1960]. The Centurions. Translated by Fielding, Xan. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0143107446.

- ^ a b Briscoe, Charles H. (2018). "The Special Forces Operator". Veritas. Vol. 14, no. 1. pp. 63–64. ISSN 1553-9830. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021.

Works cited

[edit]- Tsouras, Peter (1994). Changing Orders : The Evolution of the World's Armies, 1945 to the Present. New York: Arms and Armour. p. 352. ISBN 978-1-85409-018-8. OCLC 31136302.

External links

[edit]- U.S. Army Special Forces Command website

- U.S. Army Special Operations Command News

- United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School

- United States Special Operations Command

- Special Forces Medic talks about coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan

- Army Enlisted Jobs: Field 18 Special Forces