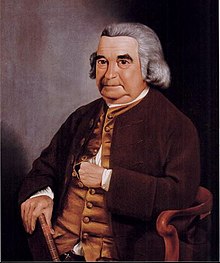

Abraham Redwood

Abraham Redwood | |

|---|---|

Abraham Redwood, 1790 | |

| Born | February 15, 1709 Antigua, Antigua and Barbuda |

| Died | March 7, 1788 (aged 79) Newport, Rhode Island, United States |

| Occupation(s) | Merchant, slave trader, plantation owner |

| Known for | Redwood Library |

Abraham Redwood (February 15, 1709 – March 7, 1788) was a West Indies merchant, slave trader, plantation owner, and philanthropist from Newport, Rhode Island. He is the namesake of the Redwood Library and Anthenaeum, one of the oldest libraries in the United States. Redwood was the President of the Redwood Library and Anthenaeum from 1747 to 1788.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Abraham Redwood Jr. was born on Antigua on February 15, 1709, at his father's plantation, Cassada Garden. Abraham Redwood Sr. was born in Bristol, England in 1665. In 1687, Redwood Sr. went to the island of Antigua, where he married Mehetable Langford, daughter of Jonas Langford. Through this marriage, Redwood Sr. took possession of the sugar plantation known as Cassada Garden which had "a great number of slaves."[2] Abraham Redwood Jr. was the third of eleven children, following his two brothers William, (d. 1712) and Jonas, (d. 1724). Redwood Sr. remained in Antigua until 1712 when he moved with his family to Salem, Massachusetts. His wife, Mehetable, died in 1715. Until his death in 1729, Redwood Sr. traveled between homes in Antigua, Salem and Newport, Rhode Island.

Abraham Redwood Jr. was educated chiefly by the Society of Friends in Philadelphia.[3] On October 27, 1724, his older brother Jonas was thrown from his horse and killed, in Newport. Upon the death of his elder brother, Abraham came into the possession of the family sugar plantation in Antigua, Cassada Garden. In 1727, Redwood Jr. purchased land on Aquidneck Island and began building his country home five miles north of Newport in Portsmouth. Sometime around 1730 he married Martha Coggeshall, of Newport, a descendant of John Coggeshall, one of the founders of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Together Martha and Abraham had six children.[3]

Redwood's botanical garden on his estate was known for its various curious foreign and indigenous plants.[4] He ordered orange and fig trees, and adolescent guava and pineapple plants from the West Indies to fill his garden.[5] Solomon Drowne wrote in 1767 that the garden was rumored to cost over forty thousand pounds, and that the gardener, Charles Dunham, received over one hundred dollars annual salary. Dunham was probably Newport's first professional gardener.

Cassada Garden

[edit]During a voyage from Bristol to Antigua in 1687, Abraham Redwood Sr. married Mehetable Langford, the daughter of a wealthy planter named Jonas Langford. Soon after his marriage, Redwood Sr. inherited the sugar cane plantation named Cassada Garden.[5] Redwood Sr.'s oldest son, William, died in 1712 at the age of sixteen, and his second son, Jonas, was thrown from his horse in 1724, at the age of eighteen. Thus the third son, Abraham Redwood Jr., became the oldest living heir, and sometime after 1724, he inherited the estate of Cassada Gardens.[2] The plantation brought Redwood an income between two and three thousand pounds a year.[6]

The name Cassada appears to be a derivative from a cassava, a plant that produces large green leaves and a tuber that has long been a source of food for Indigenous peoples of the Americas.[7]

Merchant and slave trader

[edit]Both Abraham Redwood Sr. and Abraham Redwood Jr. were devout Quakers, but that did not prevent either of them from engaging in the Atlantic slave trade.[6] In 1720, Abraham joined his father's business, working to not only maintain their sugar plantation in Antigua, but also the bilateral trade often referred to as the West Indies trade. As a part of this trade, Redwood sent timber and fish from Rhode Island to the Caribbean in exchange for molasses and hard currency.

In 1736, a sudden drop in the price of sugar in London threatened Redwood with bankruptcy.[6] Beginning in 1737, Redwood expanded his enterprise to include slave trading, becoming among the first of Newport's leading merchants to enter the slave trade.[6] In that year, he financed a voyage to West Africa on his snauw Martha and Jane. Finding success, Redwood financed two more voyages on the Martha and Jane, one in 1738 and another in 1740. Each of these voyages traveled from Newport, Rhode Island to the Gold Coast and ended in St. John's, Antigua—the site of Redwood's sugar plantation, Cassada Garden.[8] In all, Redwood may have personally financed the enslavement of over three hundred people from the region of West Africa.[9]

Redwood's 1740 slave voyage was his last one on record. However, his younger brother, William (1726–1815), and his son, Jonas (1730–1779), continued in the family business, financing four more voyages with William Vernon between 1756 and 1759.[2] The ship used for their 1757 voyage was named Cassada Garden, after the family sugar plantation. These voyages enslaved an additional five hundred people into the Atlantic slave trade.[10][9]

| Year | Vessel registered | Rig of vessel | Vessel name | Vessel owner | Captain's name | Place of purchase | Place of landing | Total enslaved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1737 | Snauw | Martha and Jane | Francis Pope | |||||

| 1738 | Newport | Snauw | Martha and Jane | Abraham Redwood | Antigua | |||

| 1740 | Newport | Snauw | Martha and Jane | Abraham Redwood | Francis Pope | Gold Coast | Antigua | |

| 1756 | Newport | Ship | Cassada Garden | William Vernon,

Jonas Redwood, William Redwood |

Thomas Teackle Taylor | Anomabu | French Caribbean | 175 |

| 1756 | Newport | Sloop | Titt Bitt | William Vernon, Jonas Redwood,

William Redwood |

Thomas Rogers | Gold Coast | ||

| 1757 | Newport | Ship | Othello | William Vernon,

Jonas Redwood, William Redwood |

Francis Malbone | Gold Coast | Barbados | 244 |

| 1759 | Newport | Snauw | Venus | Jonas Redwood, William Redwood, | Samuel Johnson | Windward, Ivory, Gold, & Benin | Martinique | 150 |

Enslaver

[edit]Abraham Redwood was one of Newport, Rhode Island's largest enslavers. Diana Redwood (1739–1822) and Newport Redwood (1716–1766) are recorded as two enslaved people Redwood kept in Newport. The 1774 Census of Newport, Rhode Island records two presumably free African householders with the surname Redwood, Cuff Redwood and Phillies Redwood.[11] Scipio and Oliver, two enslaved Africans Redwood kept on his plantation in Antigua, were burned at the stake for suspected involvement in a conspiracy to start a slave revolt in 1736.[5]

In 1775, the Society of Friends of Rhode Island, believing slavery and the Atlantic slave trade to be unchristian, formally asked Redwood to free the people he had enslaved. Redwood refused, and the Quakers disowned him. Redwood's biographer, Gladys Bolhouse, writes that Redwood, now sixty years old, "whole livelihood as well as the inheritance of his sons depended on the plantation and the plantation could not be run without slaves."[5][12]

Upon his death in 1788, Redwood transferred the enslavement of people in Newport and Antigua to his children and grandchildren. On the 1774 Census of Newport, Redwood has three African people living in his home.[12] An inventory of his Cassada Garden in Antigua showed that he enslaved two hundred and thirty-eight people.[5] In total, Redwood owned well over two hundred enslaved people, making him, at the time of his death, the largest enslaver living in the city of Newport.[5]

Philanthropy

[edit]

According to the Dictionary of National Biography, "Without a doubt the slave trade provided Redwood with the enormous profits that allowed him to become, as he was described at his death, 'the greatest public and private benefactor on Rhode Island.'"[3] Following his donation of five hundred pounds sterling to fund the library's original book collection, on August 22, 1747, an act of the Rhode Island General Assembly incorporated the Redwood Library. Redwood's donation purchased over one thousand three hundred volumes for the new library.[5] Several other prominent slave traders appear on the original list of forty-six proprietors, including William Vernon and Simon Pease.[3]

In 1764, Abraham Redwood was also one of the early benefactors of the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, later known as Brown University.[3]

Death

[edit]In 1788, Abraham Redwood died at the age of seventy-nine. Redwood is buried in the Coggeshall Burial Ground in Newport, Rhode Island.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Champlin Mason, George (1891). The Annals of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum. Newport, RI: Redwood Library.

- ^ a b c Turner, Henry Edward; Tilley, Risbrough Hammett (1881). The Rhode Island Historical Magazine. Newport Historical Publishing Company.

- ^ a b c d e Moore, Sean D. (February 14, 2019). Slavery and the Making of Early American Libraries: British Literature, Political Thought, and the Transatlantic Book Trade, 1731–1814. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-257340-7.

- ^ Johnson, Rossiter; Brown, John Howard (1904). The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans ... Biographical Society.

- ^ a b c d e f g Davis, Paul. "Abraham Redwood: Antigua and the West Indies Trade". Slavery in Rhode Island. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Deutsch, Sarah (1982). "The Elusive Guineamen: Newport Slavers, 1735–1774". The New England Quarterly. 55 (2): 229–253. doi:10.2307/365360. ISSN 0028-4866. JSTOR 365360.

- ^ "Cassada Gardens – Antigua Sugar Mills". Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Donnan, Elizabeth; Carnegie Institution of Washington (1930–1935). Documents illustrative of the history of the slave trade to America. Carnegie Institution of Washington publication no. 409. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- ^ a b c Coughtry, Jay Alan (1978). The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700–1807. University of Wisconsin—Madison.

- ^ a b "Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade – Database". www.slavevoyages.org. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Benard, Akeia A.F (January 1, 2008). "The Free African American Cultural Landscape: Newport, RI, 1774—1826". Doctoral Dissertations: 1–251.

- ^ a b Crane, Elaine Forman (1985). A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island, in the Revolutionary Era. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-1111-1.

- ^ Manuel, Elton Merritt (1939). Merchants and mansions of bygone days; an authentic account of the early settlers of Newport, Rhode Island. Newport, R.I.: R. Ward.

- 1709 births

- 1788 deaths

- People from Newport, Rhode Island

- Merchants from colonial Rhode Island

- 18th-century American merchants

- 18th-century Quakers

- American slave owners

- Philanthropists from Rhode Island

- 18th-century American planters

- Antigua and Barbuda emigrants to the United States

- People from colonial Rhode Island