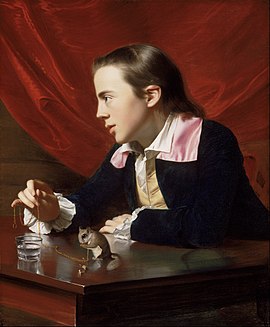

A Boy with a Flying Squirrel

| A Boy with a Flying Squirrel (Henry Pelham) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | John Singleton Copley |

| Year | 1765 |

| Medium | oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 77.15 cm × 63.82 cm (30.375 in × 25.125 in)[1] |

| Location | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

A Boy with a Flying Squirrel (Henry Pelham), or Henry Pelham (Boy with a Squirrel), is a 1765 painting by the American-born painter John Singleton Copley. It depicts Copley's teenaged half-brother Henry Pelham with a pet flying squirrel, a creature commonly found in colonial American portraits as a symbol of the sitter's refinement. Painted while Copley was a Boston-based portraitist aspiring to be recognized by his European contemporaries, the work was brought to London for a 1766 exhibition. There, it was met with overall praise from artists like Joshua Reynolds, who nonetheless criticized Copley's minuteness. Later historians and critics assessed the painting as a pivotal work in both Copley's career and the history of American art. The work was featured in exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the National Gallery of Art. As of 2023, it is held by the former.

Background

[edit]

By 1765, John Singleton Copley established himself as the foremost portrait painter of Boston's mercantile elite. Though he was familiar with European art, Copley had not yet ventured outside New England and was largely self-taught. He was at the time primarily a portraitist, but he desired to become a European-style history painter.[2] To test whether his art met English standards, Copley completed A Boy with a Flying Squirrel by early fall 1765, which was to be viewed by a London audience.[3]

Chained squirrels held by women and children were common in colonial American portraits.[4] In these works, the successful domestication of a squirrel indicated the owner's refinement and education,[4] as the training process was meant to "civilize" both the squirrel and the owner.[5] Besides A Boy with a Flying Squirrel, Copley produced two other squirrel paintings in 1765: Mrs. Theodore Atkinson and Boy with a Squirrel, John Bee Holmes.[4] Copley's 1771 portrait of Daniel Crommelin Verplanck also featured a squirrel.[6] According to the American critic Henry Theodore Tuckerman, Copley reportedly was "intimately acquainted" with the flying squirrel's natural history and had several pet flying squirrels of his own.[7]

A Boy with a Flying Squirrel's subject, Henry Pelham, was Copley's half-brother. Pelham was born in 1749, the son of Copley's widowed mother, who married Peter Pelham in 1748. Under Copley's tutelage, Pelham became a painter and engraver, as well as Copley's official business manager and assistant. Copley and Pelham held a close and affectionate relationship, as evidenced by a volume of correspondence between the two published in 1914.[7]

Description

[edit]The painting is a profile portrait of Henry Pelham seated at a table,[8][9] and the work's title has been referred to as A Boy with a Flying Squirrel (Henry Pelham),[1] Henry Pelham (Boy with a Squirrel),[10] and The Boy and the Squirrel.[8] Pelham wears a dark blue coat with a red collar, a yellow waistcoat, and a white collar[11] while his right hand holds onto a gold chain attached to his pet flying squirrel.[7] Copley rendered a variety of colors and textures, including the red drapery in the background, the highly polished mahogany table, the boy's skin, the squirrel's fur, and the reflections in the glass of water.[10] Special attention was given to the squirrel, as seen in the meticulous portrayal of its eyes and gliding membrane.[7] The squirrel is shown cracking a nut,[11] which in colonial American art, is a symbol for patience and perseverance.[7]

History

[edit]Transatlantic crossing

[edit]A Boy with a Flying Squirrel was completed while Copley was still based in Boston,[12] but it needed to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean for a spring 1766 exhibition in London at the Society of Artists of Great Britain.[3][13] Copley was aware of the risks of sea passage to artwork; he had previously lost pastels in a shipwreck in the spring of 1765. In his letters concerning A Boy with a Flying Squirrel, Copley worried about a "changing of the colours" while the painting was at sea. Thus, he assembled a professional team to facilitate the safe transport of his painting to London.[14] The painting crossed the Atlantic as part of a Mr. Roger Hale's baggage. Hale then delivered the painting to Captain R. G. Bruce, a friend of Copley's who was living in London. Bruce in turn gave the work to a Lord Cardross who took it to the studio of Britain's leading painter Sir Joshua Reynolds.[15][16]

The American-born painter Benjamin West was in London at the time and examined the painting prior to its exhibition. On first viewing the work, West was said to have exclaimed, "What delicious coloring! worthy of Titian himself!"[17] Though the painting's attribution was lost by the time it arrived at Reynolds's studio,[16] West deduced that the painter was American because the canvas was stretched over American pine.[17] A letter from Copley eventually reached West confirming Copley as the work's artist, though the painting was still mislabeled as a work by "Mr. William Copley, of Boston, New England" during the subsequent Society of Artists exhibition.[16][18]

Reception

[edit]Following A Boy with a Flying Squirrel's 1766 London exhibition, the Society of Artists encouraged Copley to come to London for artistic training and elected him a fellow in recognition of his talent.[3] Bruce eavesdropped on conversations between viewers during the exhibition and interviewed Reynolds on his opinion of the painting—all of which Bruce reported back to Copley.[16][19] According to Bruce, Reynolds commended the work as a "very wonderfull [sic] Performance". Nevertheless, Reynolds and his colleagues noted Copley's overzealous attention to detail, with Reynolds himself commenting that the composition had "a little Hardness in the Drawing, Coldness in the Shades, An over minuteness".[3] Reynolds further tempered his enthusiasm for the painting by adding that Copley needed to receive proper training before his "Manner and Taste were corrupted or fixed by working in [his] little way at Boston".[10] A Boy with a Flying Squirrel also garnered the attention of Benjamin West, who in a letter to Copley recognized "the great Honour the Picture has gaind you" but found the painting "to [sic] liney".[3] The painting's success in England encouraged Copley to make more disciplined portraits in his late American career and strengthened his conviction to move to London, which he finally did in 1774.[10][20]

Provenance and exhibition

[edit]The painting was inherited by Copley's son John Copley, 1st Baron Lyndhurst when Copley died in 1815. Following the death of Baron Lyndhurst in 1863, an 1864 Christie's auction in London sold the painting to James Sullivan Amory, husband of Copley's granddaughter Mary Copley Greene Amory. The painting was inherited in 1891 by their son Frederic Amory, and in 1928 by Copley's great-granddaughter.[21]

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, celebrated Copley's bicentennial with a February 1 to March 15, 1938 exhibition that included A Boy with a Flying Squirrel.[22] From September 19 to October 31, 1965, the painting was part of a Copley exhibition in Washington, D.C., at the National Gallery of Art.[23][24] The painting was gifted by Copley's great-granddaughter to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1978.[25] The museum's annual report for that year described the work as "the most important single gift to the collection in many years".[20] As of 2023, the painting is in the museum's Saunders Gallery among other works by Copley.[26]

Commentary

[edit]

Many 19th-century art critics considered A Boy with a Flying Squirrel to be one of Copley's most important works. According to the art historian William Dunlap, the Scottish writer Allan Cunningham judged that "of all that [Copley] ever painted, nothing surpasses his Boy and Squirrel for fine depth and beauty of colour". H. T. Tuckerman claimed in 1867 that the painting shaped Copley's "whole future career". More recently in 1976, the American art scholar John Wilmerding wrote that the work was an "early masterpiece and a significant milestone in colonial American art".[27] Some reviewers observed Copley's painting to be more than just a portrait. In 1880, the American artist and journalist S. G. W. Benjamin considered A Boy with a Flying Squirrel to be one of the artist's most important history paintings. In 1983, the art historian Trevor Fairbrother drew parallels between the painting and "European devotional pictures" as well as the French painter Jean Siméon Chardin's scenes of boys playing with cards.[28]

The art historian Jennifer Roberts believed A Boy with a Flying Squirrel to be "the most consequential painting Copley had yet produced in America". It was Copley's first major noncommissioned work and first exhibition painting. Furthermore, it was Copley's first work for a European audience, and he wanted the painting to be presentable to "the first artists in the World". In doing so, his artistic style departed from his previous work. For example, Roberts judged Copley's inclusion of a highly detailed glass of water—an element found nowhere else in Copley's other works—to be a "curiously object". overdetermined Roberts also noted Copley's "unprecedented" and "unusual" use of a profile format,[29] with A Boy with a Flying Squirrel being Copley's sole single-sitter profile painting produced in America.[30] In a broader sense, Roberts viewed the "triumph" of the painting's critical success as an "originary episode" in the history of American art. She further saw the London exhibition's "direct juxtaposition" of Copley's painting against European works as a key indication of the "emerging distinctions" between American and European art.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Roberts 2014, p. 14.

- ^ a b Roberts 2007, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e Rebora et al. 1995, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Roberts 2007, p. 25.

- ^ Rebora et al. 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Rebora et al. 1995, pp. 292–293.

- ^ a b c d e Rebora et al. 1995, p. 218.

- ^ a b Bayley 1915, p. 192.

- ^ Roberts 2014, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d Davis et al. 2003, p. 39.

- ^ a b Bayley 1915, p. 193.

- ^ Roberts 2014, p. 21.

- ^ Parker & Wheeler 1938, p. 12.

- ^ Roberts 2014, p. 22.

- ^ Roberts 2007, pp. 21, 27–28.

- ^ a b c d Roberts 2014, p. 23.

- ^ a b Martin 1883, p. 1.

- ^ Martin 1883, p. 2.

- ^ Roberts 2007, p. 28.

- ^ a b Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1978, p. 27.

- ^ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Catalog entry).

- ^ Parker & Wheeler 1938, pp. 10, 12.

- ^ Gerdts 1966, p. 278.

- ^ National Gallery of Art.

- ^ Rebora et al. 1995, p. 214.

- ^ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Saunders Gallery).

- ^ Rebora et al. 1995, pp. 215, 219.

- ^ Rebora et al. 1995, pp. 215, 218.

- ^ Roberts 2014, p. 17.

- ^ Roberts 2007, p. 29.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bayley, Frank William (1915). The Life and Works of John Singleton Copley. Taylor Press.

- Davis, Elliot Bostwick; Hirshler, Erica E.; Troyen, Carol; Quinn, Karen E.; Comey, Janet L.; Roberts, Ellen E. (2003). American Painting. MFA Publications. ISBN 978-0-8784-6660-3.

- Gerdts, William H. (1966). "Copley in Washington, New York and Boston". The Burlington Magazine. 108 (758). Burlington Magazine Publications: 278, 280–281. JSTOR 874945.

- Martin, Theodore (1883). A Life of Lord Lyndhurst: From Letters and Papers in Possession of his Family. John Murray.

- Parker, Barbara N.; Wheeler, Anne B. (1938). "The Copley Exhibition in Boston". Parnassus. 10 (2). College Art Association: 10–12. doi:10.2307/771817. JSTOR 771817. S2CID 192308121.

- Rebora, Carrie; Staiti, Paul; Hirshler, Erica E.; Stebbins, Theodore E.; Troyen, Carol; Comey, Janet L.; Quinn, Karen E. (1995). "Catalogue". John Singleton Copley in America. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-8709-9745-7.

- Roberts, Jennifer L. (2007). "Copley's Cargo: Boy with a Squirrel and the Dilemma of Transit". American Art. 21 (2). University of Chicago Press: 20–41. doi:10.1086/521888. JSTOR 10.1086/521888. S2CID 190114780.

- Roberts, Jennifer L. (2014). Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5202-5184-7.

- "A Boy with a Flying Squirrel (Henry Pelham)". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- "Gallery 128 (Saunders Gallery)". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- "John Singleton Copley: A Retrospective Exhibition". National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- "Paintings". The Museum Year: Annual Report of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 103. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: 26–29. 1978–79. JSTOR 43481828.

Further reading

[edit]- Prown, Jules David (2001). Art as Evidence: Writings on Art and Material Culture. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300084313.

- Letters and Papers of John Singleton Copley and Henry Pelham. Massachusetts Historical Society. 1914.