2022–2023 Russia–European Union gas dispute

This article needs to be updated. (January 2025) |

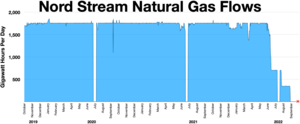

Russia cut the flow of natural gas by more than half in June because it said it could not get a part seized by the Canadian government because of sanctions.[2]

Russia halted gas flows on 11 July for annual maintenance for 10 days and resumed flows on 21 July.[3]

Russia stopped gas flows on 2 September for maintenance for three days, but has failed to resume flows since then.[4]

The Russia–EU gas dispute flared up in March 2022 following the invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Russia and the major EU countries clashed over the issue of payment for natural gas pipelined to Europe by Russia's Gazprom, amidst sanctions on Russia that were expanded in response to Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine. In June, Gazprom claimed it was obliged to cut the flow of gas to Germany by more than half, as a result of such sanctions that prevented the Russian company from receiving its turbine component from Canada. On 26 September 2022, three of the four pipes of the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines were sabotaged. This resulted in a record release of 115,000 tonnes (250 million pounds) of methane (CH4) – an equivalent of 15 million tonnes (33 billion pounds) of carbon dioxide (CO2) – and is believed to have made a contribution to global warming.[5]

As of August 2023[update], the price of gas had fallen to a fraction of the 2022 peak price and whilst Russian pipeline gas exports continued to flow in small quantities via Ukraine and via the TurkStream pipeline, provided the recipient was willing to indirectly pay in rubles,[6] the EU had found alternate sources of gas for its needs and are no longer reliant on Russia as an energy source. Arbitration cases are pending, with large claims being made against Gazprom.

Background

[edit]

Europe consumed 512 billion cubic metres (18.1 trillion cubic feet)[a] of natural gas in 2020, of which 36% (that is, 185 billion cubic metres or 6.5 trillion cubic feet) came from Russia.[7] In early 2022, with 23 pipelines between Europe and Russia in 2021,[8] Russia supplied 45% of EU's natural gas imports, earning $900 million a day.[9]

Following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the United States, the European Union,[10] and other countries,[11] introduced or significantly expanded sanctions to cut off "selected Russian banks" from SWIFT, including Gazprom bank.[12] Assets of the Central Bank of Russia held in Western nations were frozen: the Central Bank of Russia was blocked from accessing more than $400 billion in foreign-exchange reserves held abroad.[13][14]

The EU became major supporters of Ukraine, with humanitarian assistance and a growing likelihood of military assistance. Russia wanted the EU to back away from Ukraine and decided to use gas as a weapon, by threatening to cut off supplies.[15]

In March 2022, the European Commission and International Energy Agency presented joint plans to reduce reliance on Russian energy, reduce Russian gas imports by two thirds within a year, and completely by 2030.[16][17][18]

In April 2022, the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said "the era of Russian fossil fuels in Europe will come to an end".[19] On 18 May 2022, the European Union published plans to end its reliance on Russian oil, natural gas and coal by 2027.[20][18]

Demand of payment in rubles, March 2022

[edit]

On 23 March 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced payments for Russian pipeline gas would be switched from "currencies that had been compromised" (that is, US dollar and euro) to payments in roubles when the transaction involved a country formally designated "unfriendly" previously, which included all European Union states; on 28 March, he ordered the Central Bank of Russia, the government, and Gazprom to present proposals by 31 March for gas payments in rubles from these "unfriendly countries".[21][22][23] President Putin's move was construed to be aimed at forcing European companies to directly prop up the Russian currency as well as bringing Russia's Central Bank back into the global financial system after the sanctions had nearly cut it off from financial markets, essentially circumventing sanctions.[24] ING bank's chief economist, Carsten Brzeski, told Deutsche Welle he thought the gas-for-ruble demand was "a smart move".[24] At the end of April 2022, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that the $300 billion of Gazprom's funds that had in effect been "stolen" by the "Western 'friends'" were actually the funds they had paid for Russia's gas, which meant that all those years they had been consuming the Russian gas free of charge; he thus made a point that the new payment system was designed to preclude "the continuation of the brazen thievery those countries were involved in".[25][clarification needed]

On 28 March, Robert Habeck, the German Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, announced that the G7 countries had rejected the Russian President's demand that payment for gas be made in rubles.[26] On the same day, Dmitry Peskov, spokesman for the Russian president, said that Russia would "not supply gas for free".[27]

On 29 March, it was reported that the physical gas flows through the Yamal-Europe pipeline at Germany's Mallnow point had decreased to zero.[28] The following day, Habeck triggered the "early warning" level for gas supplies, the first step of a national gas emergency plan that involved setting up a crisis team of representatives from the federal and state governments, regulators and private industry and that could, eventually, lead to gas rationing; he urged Germans to voluntarily cut their energy consumption as a way of ending the country's dependence on Russia.[29][30] A similar step was undertaken by the Austrian government.[31] Meanwhile, Gazprom said it continued to supply gas to Europe via Ukraine. Russia's gas had also begun flowing westward through the pipeline via Poland.[30] Russia's TASS reported that President Putin had a phone call with Germany's Chancellor Olaf Scholz to "inform him on the decision to switch to payments in rubles for gas".[32] According to Olaf Scholz's office, President Vladimir Putin told the German Chancellor that European companies could continue paying in euros or dollars.[33]

Decree 172

[edit]On 31 March, President Vladimir Putin signed a decree – decree 172 – that obligated, starting 1 April, purchasers of Russian pipeline gas from countries on Russia's Unfriendly Countries List[34] to make their payments for Russian gas through a facility run by Russia's Gazprombank, a subsidiary of Gazprom.[35][36][37] To pay for gas, purchaser companies from "unfriendly countries" would be required to open two accounts at Gazprombank and transfer foreign currency in which they previously made payments into one of them,[38][35] which Gazprombank would then sell on the Moscow stock exchange for rubles that are deposited into the second (foreign-purchaser owned) ruble-denominated account[39] (this currency conversion would be done in Russia).[36][35] Gazprombank would then transfer this ruble payment to Gazprom PJSC (a company that operates gas pipeline systems, produces and explores gas, and transports high pressure gas in the Russian Federation and European countries[40]), at which point the purchaser would be deemed to have legally fulfilled (under Russian law) its obligations to pay.[34] Gas purchasers were thus still able to make payments by transferring foreign (non-ruble) currencies, including the currencies stipulated by their contract,[36] which in most cases were US dollars and Euros. Despite this, the obligatory new payment mechanism introduced by decree 172 has been colloquially referred to as a "demand to pay in rubles" by many media outlets.[35]

The natural gas contracts stipulated the currency in which payments to Gazprom were to be made[35] − 97% of which were in US dollars or euros[38] − as well as the accounts into which the payments were to be deposited, which were Gazprom-owned accounts at Western financial institutions. These accounts had been frozen by international sanctions and any payments deposited into these accounts would also be immediately frozen, whereas payments deposited into these Gazprombank accounts (located in Russia) would be accessible to Gazprom, which would circumvent these international sanctions.[38][41]

The first post-1 April payments were due near the end of April and in May.[36] Putin stated that any country refusing to use the new payment mechanism would be in violation of their contracts and face "corresponding repercussions".[35] The Russian government would consider a failure to pay to be a default and the existing contract would be terminated. The decree allowed exceptions to be made for buyers that would permit them to pay as before.

On 29 April 2022, a spokesperson for the German Economy Ministry said a payment through an account (such as stipulated by decree 172) is in line with sanctions when (1) “contracts have been fulfilled with payment in euros or dollars",[42] with a government source clarifying further that (2) "it was irrelevant in which country [... that] account is opened [at a bank] as long as the bank in question was not on any sanctions list."[42]

Gas delivery disruption, April 2022 – present

[edit]On 26 April 2022, Gazprom announced it would stop delivering natural gas to Poland via the Yamal–Europe pipeline and to Bulgaria from the following day as both countries had failed to make due payments to Gazprom in rubles.[43][44] Poland said it did not expect to experience disruptions due to its natural gas storage facilities being about 75% full (ensuring 40–180 days of supply), the Poland–Lithuania gas pipeline becoming operational in May 2022, and the Baltic Pipe natural gas pipeline between Poland and Norway becoming operational in October 2022, which would make Poland fully independent of Russian gas.[43][44] Poland could also import gas via the Świnoujście LNG terminal in the city of Świnoujście in the country's extreme north-west. Meanwhile, Bulgaria was almost completely dependent on Russian gas.[44]

The following day, Gazprom announced that it had "completely suspended gas supplies" to Poland's PGNiG and Bulgaria's Bulgargaz "due to absence of payments in roubles".[45] Bulgaria, Poland, and the European Union condemned the suspension.[46] The announcement of the suspension caused natural gas prices to surge[36] and the Russian ruble to reach a two-year-high against the Euro in Moscow trade.[47]

On 11 May 2022, Ukraine's state-owned gas grid operator GTSOU halted the flow of natural gas through the Sokhranovka transit point, which had transported about one third of all of piped Russian natural gas that transited through Ukraine.[48] It was the first time since the start of Russia's 24 February invasion of Ukraine that natural gas flow through Ukraine was interrupted.[48] The Ukrainian government stated that it would not reopen this pipeline unless it regained control of areas from pro-Russian fighters.[49] On the same day, Russia imposed sanctions on European subsidiaries of Gazprom which had been nationalized by European countries.[50]

On 20 May 2022, Gazprom announced that it had informed Finland that the next morning, natural gas deliveries to the country would be halted due to the refusal of the Finnish state-owned gas wholesaler to pay in rubles (that is, to comply with decree 172).[51] Natural gas accounted for 5% of Finland's total annual energy consumption, with the majority of this natural gas being supplied by Russia.[51]

On 14 June 2022, Gazprom announced it would be slashing gas flow via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, due to what it claimed was Siemens’ failure to return compressor units on time that had been sent off to Canada for repair. The explanation was challenged by Germany's energy regulator.[52][53]

On 16 June 2022, European benchmark natural gas prices increased by around 30% after Gazprom reduced Nord Stream 1's gas supply to Germany to 40% of the pipeline's capacity. Russia warned that usage of the pipeline could be completely suspended because of problems with the repairment.[54]

On 11 July 2022, Nord Stream 1 was turned off for scheduled annual maintenance, but remained off after the usual repair period.[55] The Siemens pipeline turbine was repaired in Canada. Due to sanctions, Canada could not deliver the turbine back to Russia after repair works and instead sent it to Germany, despite the call of Volodymyr Zelenskiy to maintain the sanctions.[56]

On 26 September 2022, both pipes of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, and one of the two pipes of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which connect Russia and Germany, ruptured in the Baltic Sea. Nord Stream 1 had been operating at a significantly reduced capacity and then closed for weeks, and Nord Stream 2 was not operating, but both still contained gas.[57] As of 7 October 2022, Swedish investigators said evidence pointed to sabotage.[58][59]

In October 2023, Bulgaria's government issued new transit fees on Russian gas which would aim to reduce Russia's revenues from selling the fossil fuel and discourage buyers of Russian gas. In November 2023 those fees are being challenged in the constitutional court and are also opposed by Serbia and Hungary, two regional powers which largely disagree with the EU's decision to restrict Russian gas imports, even though the fees are payable by Gazprom, not the end user.[60]

On 3 Jan’25, Gilberto Pichetto Fratin mentioned the European Union must ellobrate its price cap on gas and increase then to 60euro megawatt hour, so as to prevent from sudden energy price shock. As Ukraine has denied to renew the gas transit agreement with Russia, there are raise of fear for energy shock.[61]

Analysis of impact

[edit]With European policy-makers deciding in March 2022 to replace Russian fossil fuel imports with other fossil fuels imports and European coal energy production,[62][63] as well as due to Russia being "a key supplier" of materials used for "clean energy technologies", the reactions to the war were projected in March 2022 to have an overall negative impact on the climate emissions pathway.[64]

However, a July 2022 report from three German science academies noted that if Russian natural gas imports were to cease in the next few months, around 25% of Europe's natural gas demand could not be met at peak times for a winter similar to that in 2021 – moreover that shortfall is due to a lack of transport infrastructure such as pipeline capacity and liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and that this supply gap can be closed by 2025 if natural gas consumption falls by 20% across Europe and infrastructure is expanded simultaneously.[65]

A fully open study from Zero Lab at Princeton University published in July 2022 and based on the GenX framework concluded that reliance on Russia gas could end by October 2022 under the three core scenarios they investigated – which ranged from high coal usage to accelerated renewables deployment.[66][needs update] All three cases would result in falling greenhouse gas emissions, relative to business as usual.[66]: 7

In 2022, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Russian President Vladimir Putin planned for Turkey to become an energy hub for all of Europe.[67][needs update] According to Aura Săbăduș, a senior energy journalist focusing on the Black Sea region, "Turkey would accumulate gas from various producers — Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan, [liquefied natural gas] and its own Black Sea gas — and then whitewash it and relabel it as Turkish. European buyers wouldn’t know the origin of the gas."[68]

Alternate supplies

[edit]In May 2022 small natural gas exporter Peru increased its export of liquified natural gas to Europe, especially to Spain and the United Kingdom[69] in the first five months of 2022, by 74% compared to the same period in 2021.[69] As of September 2022, Norway, the second largest non-EU provider of gas to the EU after Russia for several decades, has been constrained by its pipeline network's structural (maximum) capacities. Prior to the opening of the Baltic Pipe, which became partially operational on 26 September 2022, Norway could only increase the volume of deliveries of natural gas to try to compensate Russia's disrupted supplies by a maximum of 5 billion cubic metres (180 billion cubic feet) to Europe, a far cry from Russia's supplies of 155 billion cubic metres (5.5 trillion cubic feet) of natural gas to the EU in 2021.[70]

On 20 May 2022, Germany and Qatar signed a declaration to deepen their energy partnership. Qatar plans to start supplying LNG to Germany in 2024.[71]

The total and operational capacity of global LNG tanker fleet as of 2021 of about 103 billion cubic metres (3.6 trillion cubic feet) was already operating at full capacity before the 2022 gas disputes. The UK and EU consume about 550 billion cubic metres (19 trillion cubic feet) of gas per year. Although the UK has three LNG terminals for gasification, much of the EU has insufficient tankers to meet its needs.[clarification needed] In late 2022, the high price attracted more tankers than available LNG import capacity.[72]

In 2023 96% of EU imports of Russian LNG went to the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Spain. The Netherlands imported very little and is quickly phasing it out. Spain has decided to not renew any LNG contracts. France and Belgium have an interest in TotalEnergies Yamal LNG project, but have not said whether they will increase or decrease purchases.[73]

On 15 June 2022, Israel, Egypt and the European Union signed a trilateral natural gas agreement.[74]

On 20 June 2022, Dutch climate and energy minister Rob Jetten announced that the Netherlands would remove all restrictions on the operation of coal-fired power stations until at least 2024 in response to Russia's refusal to export natural gas to the country. Operations were previously limited to less than a third of the total production.[75]

In January 2023, Bulgaria signed an agreement with Turkey, which would allow it to import significant amounts of Turkish gas. The European Commission expressed serious concerns about this deal, since much of the gas imported from it could have originated in Russia.[76] Bulgaria has been re-exporting significant amounts gas to the wider Southeastern European region as well.[60] Bulgaria says that the agreement with Turkey enables Bulgaria to buy LNG on the open market and for the liquified gas to be delivered to Turkey and returned to a gaseous state for pumping via the pipeline to Bulgaria. The agreement is for the use of LNG terminals and pumping gas from those terminals to Bulgaria.[77]

By 2023, EU had an LNG import capacity of 157 billion cubic metres per year (5.5 trillion cubic feet per year),[78] in excess of what had been utilized in 2022.[79] Some terminals were fully booked for 2023,[80][81] while others had open time slots for further import.[82][83][needs update]

Price cap sanction

[edit]The European Energy ministers agreed, on 19 December 2022, on a price cap for natural gas at €180 per megawatt-hour.[84]

The objective being to stabilise and avoid major upward fluctuations in gas prices.

Position July 2023

[edit]Gas pipeline routes from Russia

[edit]As of January 2025 only One of the five major pipelines connecting Russia and Europe are still operational:[8][73]

- Nord Stream 1 – ceased September 2022 – both pipes damaged by explosions

- Nord Stream 2 – never used – one pipe damaged by explosion – one theoretically possible to use

- Yamal – through Belarus and Poland – ceased May 2022 – Poland took over the 48% Gazprom share of the pipe in Poland in 2023 and does not want to reopen the pipeline

- Ukraine transit – one route operational with around 13 billion cubic metres per year (460 billion cubic feet per year), the other is closed as it is in the war zone. Contract runs until end of 2024 when Ukraine says it will then stop the flow of Russian gas. Gas transits Ukraine to Slovakia (6.5 billion cubic metres or 230 billion cubic feet) and on to Austria (6 billion cubic metres or 210 billion cubic feet) and Hungary (1 billion cubic metres or 35 billion cubic feet)

- Turkstream – via Turkey and Bulgaria, capacity of 15.75 billion cubic metres (556 billion cubic feet), operational with around 12 billion cubic metres per year (420 billion cubic feet per year) – transiting on to Serbia (2.2 billion cubic metres or 78 billion cubic feet), Hungary (3.5 billion cubic metres or 120 billion cubic feet), Bosnia (0.4 billion cubic metres or 14 billion cubic feet), North Macedonia (0.4 billion cubic metres or 14 billion cubic feet), and Greece (3 billion cubic metres or 110 billion cubic feet)

In 2021, Russian piped gas supplied to Europe was 155 billion cubic metres (5.5 trillion cubic feet),[70] in 2022 it was around 62 billion cubic metres (2.2 trillion cubic feet) and just 28 billion cubic metres (0.99 trillion cubic feet) in 2023.

Contractual position

[edit]Gas companies in all EU countries had contracts with Gazprom to supply certain amounts of gas for a set number of years, most have not been fulfilled. The position in July 2023 was contracts falling into three categories:[73]

- Terminated – around 30 billion cubic metres per year (1.1 trillion cubic feet per year) have been terminated – being those that had reached the end of their contract period or had been officially terminated

- Poland, 10.2 billion cubic metres (0.36 trillion cubic feet), expired late 2022, supplies suspended in April 2022 after Poland refused to pay in rubles

- Bulgaria, 2.96 billion cubic metres (0.105 trillion cubic feet), expired late 2022, supplies suspended in May 2022 after Bulgaria refused to pay in rubles

- Finland, 3 billion cubic metres (0.11 trillion cubic feet), supplies suspended in May 2022 after refusal to pay in rubles, Gazprom went to arbitration against Gasum for the unpaid gas, which arbitration decided was payable, but not in rubles.[85]

- Czech Republic and Slovenia expired late 2022 but suffered shortfalls in delivery after Nord Stream ceased operating. The Czech gas company ČEZ Group went to ICC arbitration to recover damages of $45 million.[86]

- Under legal review – around 73 billion cubic metres per year (2.6 trillion cubic feet per year) with contracts running to 2030 to 2035 are short or no longer being supplied by Gazprom.

- Germany, 35 billion cubic metres (1.2 trillion cubic feet), supplies ceased due to Nord Stream or the refusal to pay in rubles resulting in supplies being terminated. Many companies are seeking arbitration, Uniper is claiming €11.6 billion compensation from Gazprom[87]

- Italy, 22 billion cubic metres (0.78 trillion cubic feet), received around 15% of contracted amount, even though it was prepared to pay in rubles

- France, 13.5 billion cubic metres (0.48 trillion cubic feet), suffered reduced supplies after Nord Stream stopped, Engie opened arbitration proceedings in February 2023 for short delivery[88]

- Denmark, 1.9 billion cubic metres (0.067 trillion cubic feet), Ørsted had its supply suspended in July 2022 after refusing to pay in rubles

- Active – 25 billion cubic metres per year (0.88 trillion cubic feet per year) with 10 contracts generally receiving their contracted amounts, with minor interruptions

- via Ukraine, which may terminate in December 2024 when transit agreement ends

- Austria, 6 billion cubic metres (0.21 trillion cubic feet), contracted until 2040, with OMV paying in rubles

- Slovakia, 6.5 billion cubic metres (0.23 trillion cubic feet), contracted until 2028, paying in rubles

- Hungary, 1.0 billion cubic metres (0.035 trillion cubic feet), part of national supply

- via Turkstream, routing though Bulgaria, which dramatically increased their transit fee in late 2023 to 20 levs (€10.22) per MWh.[89]

- Hungary, 3.5 billion cubic metres (0.12 trillion cubic feet), increased in August 2022 with an extra 2.1 billion cubic metres (0.074 trillion cubic feet) contract

- Serbia, 2.2 billion cubic metres (0.078 trillion cubic feet), contracted until 2026

- Croatia, 1.1 billion cubic metres (0.039 trillion cubic feet), contracted until 2027

- North Macedonia, 0.43 billion cubic metres (0.015 trillion cubic feet), contracted until 2027

- Bosnia, 0.4 billion cubic metres (0.014 trillion cubic feet), 1 year deal

- Greece, 3.0 billion cubic metres (0.11 trillion cubic feet), different contract dates, some as LNG

- via Ukraine, which may terminate in December 2024 when transit agreement ends

Overall impact of dispute

[edit]The dispute arose because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, with Russia using the EU's reliance on Russian gas as leverage against the EU to move the EU away from Ukraine and reduce sanctions being applied against Russia.[15]

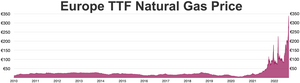

The effect of the EU response to the dispute is clear when you consider that European gas prices went above €200/MWh in 2022, but by August 2023 the price had dropped to around €30, and with EU gas storage near full,[90] some companies began storing gas in war-torn Ukraine.[91] EU autumn gas storage goals were achieved early in 2022 and 2023, and levels were at a record high of 59% at the end of winter on 1 April 2024.[18]

The mass departure of most EU countries from using Russian piped gas in 2022, whether voluntarily or being forced due to Russia ceasing supplies, will have a long term impact on both the EU and Russia, with Russia losing both political influence and massive amounts of taxation and company profits. Russia is unlikely to make inroads into the EU's future energy policy.[92]

The EU found new suppliers in 2022, initially at a higher price, which had a cost, including high inflation; however, the price of world gas had fallen to acceptable levels by 2023, and with the EU determined to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, a major boost has been given to renewable energy sources.[93]

See also

[edit]- 2021–2023 global energy crisis – Worldwide crisis affected by shortage of energy supplies

- Economic impact of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine – Financial crisis beginning after the invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions

- 2022 Russian oil price cap – Economic sanction following the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- German economic crisis (2022–present)

- Strategic natural gas reserve

- Lukoil oil transit dispute

Notes

[edit]- ^ 1 billion cubic metres (35 billion cubic feet) equals 1 bcm.

References

[edit]- ^ "Network Data". Nord-stream.info. Archived from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Canada seeking pathway to enable German gas flow amid Russian sanctions -Bloomberg". Reuters. 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Mazneva, Elena; Almeida, Isis (21 July 2022). "Russia Resumes Nord Stream Gas Flow, Bringing Europe Respite". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Steitz, Christoph; Davis, Caleb (3 September 2022). "Russia scraps gas pipeline reopening, stoking European fuel fears". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Sanderson, Hans; Czub, Michał; Jakacki, Jaromir; Koschinski, Sven; Tougaard, Jakob; Sveegaard, Signe; Frey, Torsten; Fauser, Patrik; Bełdowski, Jacek; Beck, Aaron J.; Przyborska, Anna; Olejnik, Adam; Szturomski, Bogdan; Kicinski, Radoslaw (14 November 2023). "Environmental impact of the explosion of the Nord Stream pipelines". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 19923. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-47290-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10646109. PMID 37964081.

- ^ Kelly, Andrew, ed. (17 August 2023). "Russia's Pipeline Gas Exports to Europe Pick Up". Energy Intelligence.

- ^ Poljak, John (4 May 2022). "Could Europe replace Russian gas with green hydrogen? Let's look at the numbers". Recharge. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Gas Infrastructure Europe – System Development Map 2022/2021" (PDF). European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG). December 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Stastna, Kazi (12 April 2022). "Missiles fly, but Ukraine's pipeline network keeps Russian gas flowing to Europe". CBC News. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Melander, Ingrid; Gabriela, Baczynska (24 February 2022). "EU targets Russian economy after 'deluded autocrat' Putin invades Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Western Countries Agree To Add Putin, Lavrov To Sanctions List". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 25 February 2022. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Collins, Kaitlan; Mattingly, Phil; Liptak, Kevin; Judd, Donald (26 February 2022). "White House and EU nations announce expulsion of 'selected Russian banks' from SWIFT". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Horsley, Scott (28 February 2022). "In an effort to choke Russian economy, new sanctions target Russia's central bank". NPR. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia; Smialek, Jeanna (28 February 2022). "The West's Plan to Isolate Putin: Undermine the Ruble". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022.

- ^ a b Oltermann, Philip; Henley, Jon; Chrisafis, Angelique; Jones, Sam; Walker, Shaun (3 February 2023). "How Putin's plans to blackmail Europe over gas supply failed". The Guardian.

- ^ Weise, Zia (8 March 2022). "Commission plans to get EU off Russian gas before 2030". Politico. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "A 10-Point Plan to Reduce the European Union's Reliance on Russian Natural Gas". IEA. March 2022. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Gas storage". energy.ec.europa.eu.

- ^ Karimli, Ilham (4 June 2022). "Azerbaijan, EU Working to Expand Natural Gas Supplies to Europe". Caspian News. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Abnett, Kate (18 May 2022). "EU unveils 210 bln euro plan to ditch Russian fossil fuels". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Путин поручил поставлять газ в недружественные страны только за рубли" (in Russian). TASS. 23 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Putin Orders Preparation Of Proposals For 'Unfriendly Countries' To Pay In Rubles For Gas". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 28 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Russia issues list of 'unfriendly' countries amid Ukraine crisis". Al Jazeera. 8 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b Ehrhardt, Mischa (24 March 2022). "Putin's gas-for-rubles plan set to worsen EU energy crunch". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Лавров заявил, что Запад украл у России более $300 млрд, забрав деньги за российский газ" (in Russian). TASS. 29 April 2022. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "G7 rejects Russia's demand for gas payment in rubles". Deutsche Welle. 28 March 2022. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Teslova, Elena (28 March 2022). "Russia says no free gas deliveries if Europe refuses to pay in rubles". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Gas flows via Yamal-Europe pipeline fall to zero, other flows steady". Reuters. 29 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Gehrke, Laurenz (30 March 2022). "Germany calls for people to cut energy use as response to Russian threat". Politico. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b Eddy, Melissa (30 March 2022). "Germany moves toward gas rationing in a standoff over ruble payments". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Espiner, Tom; Race, Michael (30 March 2022). "Germany and Austria take step towards gas rationing". BBC. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Путин информировал Шольца о сути решения о переходе к оплате газа в рублях" (in Russian). TASS. 30 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Germany says Putin agreed to keep payments for gas in euros". Deutsche Welle. 30 March 2022. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b Davies, Rob; Elliott, Larry (28 April 2022). "How EU energy firms plan to pay for Russian gas without breaking the law". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Putin Signs Decree Creating Ruble Payment System For Russian Gas To Bolster Currency". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 31 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Cocklin, Jamison (11 April 2022). "LNG 101: How Russia Expects to Receive Rubles for European Natural Gas Deliveries". Natural Gas Intelligence. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 31.03.2022 № 172 ∙ Официальное опубликование правовых актов ∙ Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации". publication.pravo.gov.ru. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Abnett, Date (22 April 2022). "EU says pay for Russian gas in euros to avoid breaching sanctions". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

In March it issued a decree proposing that energy buyers open accounts at Gazprombank to make payments in euros or dollars, which would then be converted to roubles. The Commission said companies should continue to pay the currency agreed in their contracts with Gazprom - 97% of which are in euros or dollars. "Companies with contracts stipulating payments in euros or dollars should not accede to Russian demands. This would be contrary to the sanctions in place," a Commission spokesperson said.

- ^ Abnett, Kate; Guarascio, Francesco (28 April 2022). "Europe struggles for clarity on Russia's roubles-for-gas scheme". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "GAZP: Gazprom PJSC Stock Price Quote - MICEX Main - Bloomberg". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Abnett, Kate (27 April 2022). "What is the EU's stance on Russia's roubles gas payment demand?". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b Wacket, Markus (29 April 2022). "Gazprombank account not necessarily breach of sanctions, German economy ministry says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b Sawicki, Bartłomiej (26 April 2022). "Gazprom zakręcił Polsce kurek z gazem. Premier potwierdza groźby" [Gazprom has turned off the gas tap in Poland. The prime minister confirms the threats]. Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Russian demand for ruble gas payments causes first shutdowns in Poland, Bulgaria". Deutsche Welle. 26 April 2022. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Cocklin, Jamison (27 April 2022). "Global Natural Gas Prices Surge and Uncertainty Reigns After Russia Cuts Supplies to Poland, Bulgaria". Natural Gas Intelligence. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Tsolova, Tsvetelia; Koper, Anna (27 April 2022). "Europe decries 'blackmail' as Russia cuts gas to Poland, Bulgaria". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Rouble hits over 2-year high vs euro in Moscow as Russia halts some gas supplies". Reuters. 27 April 2022. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b Chestney, Nina (11 May 2022). "Russian gas flows to Europe via Ukraine fall after Kyiv shuts one route". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Kauranen, Anne; Landay, Jonathan (12 May 2022). "Moscow warns Finland over NATO bid as Ukraine says Russian ship damaged". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ "Europe faces gas supply disruption after Russia imposes sanctions". Al Jazeera. 12 May 2022. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ a b Kauranen, Anne; Buli, Nora (20 May 2022). "Russia to halt gas flows to Finland on Saturday". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Chambers, Madeline; Steitz, Christoph (15 June 2022). "RNord Stream 1 gas supply cut aimed at sowing uncertainty, Germany warns". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Factbox: The three stages of Germany's emergency gas plan". Reuters. 23 June 2022. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Chestney, Nina (16 June 2022). "Russian gas flows to Europe fall, hindering bid to refill stores". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "Maintenance Works". Nord stream. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Canada sends repaired Nord Stream turbine to Germany, Kommersant reports". Reuters. 18 July 2022. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Helman, Christopher (27 September 2022). "Sabotage Suspected As Russian Gas Leaks From Ruptured Nord Stream Pipelines In The Baltic Sea". Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Stärkt misstanke om grovt sabotage i Östersjön" (Press release) (in Swedish). Swedish Security Service. 6 October 2022. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Christina (6 October 2022). "Swedish investigators say the evidence in pipeline leaks points to sabotage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ a b Jack, Victor; Gavin, Gabriel (10 November 2023). "Bulgaria's Russian gas games rile Europe". POLITICO. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ "Italy calls for EU gas price cap at 60 euros per megawatt hour". Reuters. 3 January 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Jordans, Frank (21 March 2022). "UN chief: Don't let Russia crisis fuel climate destruction". AP News. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ "EU warns of fossil fuel 'backsliding' as countries turn to coal". Al Jazeera. 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Geman, Ben (14 March 2022). "The climate spillover of Russia's invasion of Ukraine". Axios. Archived from the original on 12 April 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Sauer, Dirk Uwe; Pittel, Karen; Fischedick, Manfred; Erlach, Berit; Gierds, Jörn; Stephanos, Cyril (July 2022). Welche Auswirkungen hat der Ukrainekrieg auf die Energiepreise und Versorgungssicherheit in Europa? [What impact will the Ukraine war have on energy prices and security of supply in Europe?] (in German). Germany: acatech, Leopoldina, Akademienunion. doi:10.48669/esys_2022-5. Archived from the original on 24 July 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022. Launched 14 July.

- ^ a b Lau, Michael; Ricks, Wilson; Patankar, Neha; Jenkins, Jesse (8 July 2022). Pathways to European independence from Russian natural gas — Policy memo. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Zero Lab, Princeton University. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6811675. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022. DOI resolves to latest version. License information from Zenodo landing page. You may need to sort through the file listings to locate the appropriate PDF.

- ^ Jones, Dorian (20 October 2022). "Erdogan Agrees to Putin's Plan for Turkey to Be Russian Gas Hub". VOA News.

- ^ Gavin, Gabriel (4 May 2023). "Erdoğan plays energy card in Turkish election — with Putin's help". Politico.

- ^ a b Aquino, Marco; Parraga, Marianna (31 May 2022). "In Latam, Peru streaks ahead in LNG race to Europe as Trinidad stumbles". Reuters. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ a b Lambert, Laurent; Tayah, Jad; Lee-Schmidt, Caroline; Abdalla, Monged (September 2022). "The EU's natural gas Cold War and diversification challenges". Energy Strategy Reviews. 43: 100934. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2022.100934. S2CID 251715432.

- ^ "Germany signs energy partnership with Qatar". Deutsche Welle. 20 May 2022. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Rashad, Marwa; Carreño, Belén (18 October 2022). "Dozens of LNG-laden ships queue off Europe's coasts unable to unload". Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Do future Russian gas pipeline exports to Europe matter anymore?" (PDF). July 2023.

- ^ "EU signs gas deal with Israel, Egypt in bid to ditch Russia". Al Jazeera. 15 June 2022. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Dutch join Germany, Austria, in reverting to coal". Agence France-Presse. 20 June 2022. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Jack, Victor; Gavin, Gabriel (25 August 2023). "Bulgaria-Turkey deal opens the door for Russian gas". POLITICO. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ "Bulgaria signs long-term agreement to use Turkish gas terminals". 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Liquefied natural gas infrastructure in the EU - Consilium".

- ^ "European LNG Tracker". ieefa.org.

- ^ "Greece's DESFA says all Revithoussa LNG slots booked in 2023". LNG Prime. 2 February 2023.

- ^ "Deutsche ReGas says Mukran LNG capacity booked". LNG Prime. 9 August 2023.

- ^ "Available LNG capacities on sale". www.fluxys.com.

- ^ "Spanish LNG imports, reloads down in July". LNG Prime. 9 August 2023.

- ^ "Reuters: EU countries agree on Russian gas price cap". 4 June 2016. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "Finland's Gasum says tribunal ruled it does not have to pay Gazprom in roubles". Reuters. 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Czech energy group brings ICC claim against Gazprom". 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Uniper brings claim against Gazprom". 30 November 2022.

- ^ "Engie launches arbitration action against Gazprom over lack of gas deliveries". 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Lukoil Bulgaria refinery attracts buyer interest - report". SeeNews. 18 October 2023.

- ^ Caldwell, Alan (8 August 2023). "European Natural Gas Prices Ease Amidst Rising Stockpiles". EnergyPortal.eu.

- ^ Lopatka, Jan; Strzelecki, Marek (8 August 2023). "Exclusive: Defying war risk, European traders store gas in Ukraine". Reuters.

- ^ "Own goal: How Russia's gas war has backfired". 27 July 2023.

- ^ "The impact of the gas supply crisis on the Just Transition Plans" (PDF). April 2023.

- 2022 in economic history

- 2023 in economic history

- 2022 in international relations

- 2023 in international relations

- 2022 in Russia

- 2023 in Russia

- 2022 in the European Union

- 2023 in the European Union

- Events affected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Energy crises

- Energy policy

- Energy policy of Russia

- Price disputes involving Gazprom

- Natural gas in Russia

- Natural resource conflicts

- Russia–European Union relations

- Vladimir Putin

- Von der Leyen Commission