2020 United States redistricting cycle

This article needs to be updated. (September 2024) |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States |

|---|

|

The 2020 United States redistricting cycle is in progress following the completion of the 2020 United States census. In all fifty states, various bodies are re-drawing state legislative districts. States that are apportioned more than one seat in the United States House of Representatives are also drawing new districts for that legislative body.

The rules for redistricting vary from state to state, but all states draw new legislative and congressional maps either in the state legislature, in redistricting commissions, or through some combination of the state legislature and a redistricting commission. Though various laws and court decisions have put constraints on redistricting, many redistricting institutions continue to practice gerrymandering, which involves drawing new districts with the intention of giving a political advantage to specific groups.[1] Political parties prepare for redistricting years in advance, and partisan control of redistricting institutions can provide a party with major advantages.[2] Aside from the possibility of mid-decade redistricting,[3] the districts drawn in the 2020 redistricting cycle will remain in effect until the next round of redistricting following the 2030 United States census.

United States House of Representatives

[edit]Reapportionment

[edit]| State | Seats[4][5] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current | New | Change | |

| 53 | 52 | ||

| 36 | 38 | ||

| 27 | 28 | ||

| 27 | 26 | ||

| 18 | 17 | ||

| 18 | 17 | ||

| 16 | 15 | ||

| 14 | 14 | ||

| 13 | 14 | ||

| 14 | 13 | ||

| 12 | 12 | ||

| 11 | 11 | ||

| 10 | 10 | ||

| 9 | 9 | ||

| 9 | 9 | ||

| 9 | 9 | ||

| 9 | 9 | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||

| 7 | 8 | ||

| 8 | 8 | ||

| 7 | 7 | ||

| 7 | 7 | ||

| 6 | 6 | ||

| 6 | 6 | ||

| 5 | 6 | ||

| 5 | 5 | ||

| 5 | 5 | ||

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 4 | 4 | ||

| 3 | 3 | ||

| 3 | 3 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 3 | 2 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 1 | 2 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

Article One of the United States Constitution establishes the United States House of Representatives apportions representatives to the states based on population, with reapportionment occurring every ten years. The decennial United States census determines the population of each state. Each of the fifty states is guaranteed at least one representative, and the Huntington–Hill method is used to assign the remaining 385 seats to states based on the population of each state. Congress has provided for reapportionment every ten years since the enactment of the Reapportionment Act of 1929. Since 1913, the U.S. House of Representatives has consisted of 435 members, a number set by statute, though the number of representatives temporarily increased in 1959. Reapportionment also affects presidential elections, as each state is guaranteed electoral votes equivalent to the number of representatives and senators representing the state.[citation needed]

Prior to the 2022 U.S. House elections, each state apportioned more than one representative will draw new congressional districts based on the reapportionment following the 2020 census. Based on the official counts of the 2020 census, California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia each lost one seat, while Colorado, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon each gained one seat, and Texas gained two seats. Though California lost a seat for the first time in its history, the 2020 census continued a broader trend of Northeastern and Midwestern states losing seats and Western and Southern states gaining seats.[6]

| Eliminated districts | Created districts |

|---|---|

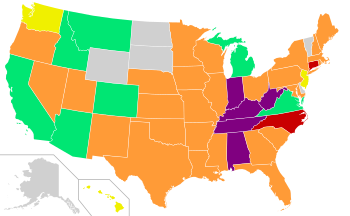

Congressional redistricting methods

[edit]

Each U.S. representative represents one congressional district, which encompasses all or part of a single state. Every state with more than one congressional district must pass a new redistricting plan before the filing deadlines of the 2022 elections.[10] In most states, the state legislature draws the new districts, but some states have established redistricting commissions.[11] Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Michigan, and Washington use independent commissions to draw House districts, while Hawaii and New Jersey use "politician commissions" to draw House districts.[11] Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont and Wyoming will continue to have only one representative in the House, and so will not have to draw new House districts.

In all other states, the legislature draws district lines, although some states have advisory commissions that can play a major role in drawing lines, and other states have backup commissions if the state legislature is unable to draw the lines itself.[11] In many states, districts are drawn with the intent to benefit certain political groups, including one of the two major political parties, in a practice known as gerrymandering. Most states draw new lines by passing a law the same way any other law is passed, but some states have special procedures.[11] Connecticut and Maine require a two-thirds super-majority in each house of the state legislature for redistricting plans, while district lines are not subject to gubernatorial veto in Connecticut and North Carolina.[11] The Ohio redistricting process is designed to encourage the legislature to pass a map with bipartisan support, but the majority party can pass maps that last for four years (as opposed to the normal ten years) without the support of the minority party.[12] The legislatures of Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia can override gubernatorial vetoes with a simple majority vote,[13] giving governors in those states little leverage in the drawing of new district maps.

Limits on congressional redistricting

[edit]Though the states have wide latitude in the re-drawing of congressional districts, state power over redistricting is subject to limits set by the U.S. Constitution, rulings of the federal judiciary and statutes passed by Congress. In the case of Wesberry v. Sanders, the Supreme Court of the United States established that states must draw districts that are equal in population "as nearly as is practicable." Subsequent court cases have required states to redistrict every ten years, although states can redistrict more often than that depending on their own statutes and constitutional provisions.[14] Since the passage of the Uniform Congressional District Act (Pub. L. 90–196, 81 Stat. 581, enacted December 14, 1967), most states have been barred from using multi-member districts; all states currently use single-member districts.[15] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 establishes protections against racial redistricting plans that would deny minority voters an equal opportunity to elect representatives of their choice. The Supreme Court case of Thornburg v. Gingles established a test to determine whether redistricting lines violate the Voting Rights Act. In some states, courts have required the creation of majority-minority districts.[16]

In addition to standards required by federal law, many states have also adopted other criteria, including compactness, contiguity, and the preservation of political subdivisions (such as cities or counties) or communities of interest.[17] Some states, including Arizona, Colorado, New York and Washington require the drawing of competitive districts.[17]

Control of congressional redistricting

[edit]

Congressional redistricting plans passed by legislature

[edit]The table shows the partisan control of states in which congressional redistricting is enacted through either a bill or a joint resolution passed by the legislature. States in which the governor can technically veto the bill, but that veto can be overridden by a simple majority of the state legislature, are marked as "simple maj. override".

| State | Seats[20] | Partisan control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Governor | Senate | House | ||

| Alabama | 7 | Republican | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Arkansas | 4 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Connecticut | 5 | Split*‡ | No veto | Democratic | Democratic |

| Florida | 28 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Georgia | 14 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Illinois | 17 | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| Indiana | 9 | Republican‡ | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Iowa | 4 | Republican† | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Kansas | 4 | Republican | Democratic↑ | Republican | Republican |

| Kentucky | 6 | Republican | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Louisiana | 6 | Split | Democratic | Republican | Republican |

| Maine | 2 | Split*† | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| Maryland | 8 | Democratic | Republican↑ | Democratic | Democratic |

| Massachusetts | 9 | Democratic | Republican↑ | Democratic | Democratic |

| Minnesota | 8 | Split | Democratic | Republican | Democratic |

| Mississippi | 4 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Missouri | 8 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Nebraska | 3 | Nonpartisan | Republican | Nonpartisan | |

| Nevada | 4 | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| New Hampshire | 2 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| New Mexico | 3 | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| New York | 26 | Democratic* | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| North Carolina | 14 | Republican | No veto | Republican | Republican |

| Ohio | 15 | Republican† | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Oklahoma | 5 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Oregon | 6 | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| Pennsylvania | 17 | Split | Democratic | Republican | Republican |

| Rhode Island | 2 | Democratic† | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| South Carolina | 7 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Tennessee | 9 | Republican | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Texas | 38 | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Utah | 4 | Republican† | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| West Virginia | 2 | Republican | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Wisconsin | 8 | Split | Democratic | Republican | Republican |

"*" indicates that a 2/3 super-majority vote is required in the legislature

"↑" indicates that one party can override a gubernatorial veto because of a supermajority in the legislature

"†" indicates that the state employs an advisory commission

"‡" indicates that the state employs a back-up commission

Ohio requires certain qualified majorities, at each stage of its congressional redistricting process, for its congressional maps to endure (subject to judicial review) for the full decade.

Congressional redistricting plans passed by commissions

[edit]| State | Seats[20] | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 9 | Independent commission |

| California | 52 | Independent commission |

| Colorado | 8 | Independent commission |

| Idaho | 2 | Independent commission |

| Hawaii | 2 | Politician commission |

| Michigan | 13 | Independent commission |

| Montana | 2 | Independent commission |

| New Jersey | 12 | Politician commission |

| Virginia | 11 | Hybrid commission |

| Washington | 10 | Independent commission |

Six states with multiple members of the House of Representatives use independent commissions to draw congressional districts. In Arizona, Montana, and Washington, the four party leaders of the state house and state senate each select one member of the Independent Redistricting Commission, and these four members select a fifth member who is not affiliated with either party. In California, the Citizen's Redistricting Commission consists of five Democrats, five Republicans, and four individuals who are not members of either party. In Idaho, the four party leaders of the state house and state senate and the chairmen of the two most popular state parties (based on the results of the most recent gubernatorial vote) each select a member of the Commission for Reapportionment.[21]

Two states use politician commissions to draw congressional districts. In Hawaii, the president of the state senate and the speaker of the state house each select two members of the Reapportionment Commission, while the minority parties in both chambers each appoint two members of the commission. The eight members of the commission then select a ninth member, who also chairs the commission. In New Jersey, the four party leaders of the state house and state senate and the party leaders of the two largest parties each choose two members of the Apportionment Commission, and the twelve members of the commission select a thirteenth member to chair the commission.[21]

One state, Virginia, uses a hybrid, bipartisan commission consisting of eight legislators and eight non-legislator citizens. The commission is evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans.[22]

Ohio employs a hybrid commission as a back-up redistricting authority in the case of the state legislature failing to achieve a certain qualified majority for approval of a map. The commission is composed of elected political officials as well as appointments made by the leaders of the state legislative chambers (namely: the speaker of the house, the leader of the largest party in the house to which the speaker of the house does not belong, the president of the senate, and the leader of the largest party in the senate to which the speaker of the senate does not belong), although those appointments also were politicians in the 2020 cycle. If the redistricting commission fails to achieve a certain qualified majority for approval of a congressional redistricting plan when it has been charged to do so, the authority to pass such a plan transfers back to the state legislature, which may then pass a plan either for the full decade via a certain qualified majority, or for only four years via normal legislative procedure otherwise.[citation needed]

State legislatures

[edit]Legislative redistricting methods

[edit]

Each state draws new legislative district boundaries every ten years. Every state except Nebraska has a bicameral legislative branch. Nebraska is also unique in that it has the only legislative body that is officially non-partisan. Most states must pass redistricting plans by the time of the filing deadlines for the 2022 elections. The exceptions are Virginia and New Jersey, which must pass new plans in 2021, Louisiana and Mississippi which have a 2023 deadline, and Montana, which has a 2024 deadline.[10]

Fifteen states use independent or politician commissions to draw state legislative districts. In the other states, the legislature is ultimately charged with drawing new lines, although some states have advisory or back-up commissions. Connecticut, Illinois, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas have backup commissions that draw district lines if the legislature is unable to agree on new districts. Iowa, Maine, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont employ advisory commissions. In Oregon, the Secretary of State will draw the legislative districts if the legislature fails to do so. In Connecticut and Maine, a 2/3 super-majority vote in each house is required to create new districts, while in Connecticut, Florida, Maryland, Mississippi, and North Carolina, the governor cannot veto redistricting plans.[23] The legislatures of Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia can override gubernatorial vetoes with a simple majority vote,[13] giving governors in those states little leverage in the drawing of new district maps.

Limits on state legislative redistricting

[edit]The states have wide latitude in re-drawing legislative districts, but the U.S. Supreme Court case of Reynolds v. Sims established that states must draw districts that are "substantially equal" in population to one another. Federal court cases have established that deviation between the largest and smallest districts generally cannot be greater than ten percent, and some states have laws requiring less deviation. Court cases have also required states to redistrict every ten years, although states can redistrict more often than that depending on their own statutes and constitutional provisions.[14] States are free to employ multi-member districts, and different districts can elect different numbers of legislators.[24] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 establishes protections against racial redistricting plans that would deny minority voters an equal opportunity to elect representatives of their choice. The Supreme Court case of Thornburg v. Gingles established a test to determine whether redistricting lines violate the Voting Rights Act.[16]

Many states have also adopted other criteria, including compactness, contiguity, and the preservation of political subdivisions (such as cities or counties) or communities of interest.[17] Some states, including Arizona, require the drawing of competitive districts,[17] while other states require the nesting of state house districts within state senate districts.[25]

Control of legislative redistricting

[edit]

State legislative redistricting plans passed by legislature

[edit]The table shows the partisan control of states in which state legislative redistricting is enacted via a bill passed by the legislature. States in which the governor can technically veto the bill, but that veto can be overridden by a simple majority of the state legislature, are marked as "simple maj. override".

| State | Control | Governor | State Senate |

State House |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Republican | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Connecticut | Split*‡ | No veto | Democratic | Democratic |

| Delaware | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| Florida | Republican | No veto | Republican | Republican |

| Georgia | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Illinois‡ | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| Indiana | Republican‡ | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Iowa | Republican† | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Kansas | Republican | Democratic↑ | Republican | Republican |

| Kentucky | Republican | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Louisiana | Split | Democratic | Republican | Republican |

| Maine | Split*† | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| Maryland | Democratic | Republican↑ | Democratic | Democratic |

| Massachusetts | Democratic | Republican↑ | Democratic | Democratic |

| Minnesota | Split | Democratic | Republican | Democratic |

| Mississippi | Republican‡ | No veto | Republican | Republican |

| Nebraska | Nonpartisan | Republican | Nonpartisan | |

| Nevada | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| New Hampshire | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| New Mexico | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| New York | Democratic*† | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| North Carolina | Republican | No veto | Republican | Republican |

| North Dakota | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Oklahoma | Republican‡ | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Oregon | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| Rhode Island | Democratic† | Democratic | Democratic | Democratic |

| South Carolina | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| South Dakota | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Tennessee | Republican | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Texas | Republican‡ | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Utah | Republican† | Republican | Republican | Republican |

| Vermont | Split† | Republican | Democratic | Democratic |

| West Virginia | Republican | Simple maj. override | Republican | Republican |

| Wisconsin | Split | Democratic | Republican | Republican |

| Wyoming | Republican | Republican | Republican | Republican |

An * indicates that a 2/3 super-majority vote is required in the legislature

A ↑ indicates that one party can override a gubernatorial veto because of a super-majority in the legislature

A † indicates that the state employs an advisory commission

A ‡ indicates that the state employs a backup commission

State legislative redistricting plans passed by commission

[edit]| State | Type | Partisan control |

|---|---|---|

| Alaska | Independent | — |

| Arizona | Independent | — |

| Arkansas | Politician | Republican |

| California | Independent | — |

| Colorado | Independent | — |

| Hawaii | Politician | Bipartisan |

| Idaho | Independent | — |

| Michigan | Independent | — |

| Missouri | Politician | Bipartisan |

| Montana | Independent | — |

| New Jersey | Politician | Bipartisan |

| Ohio | Politician | Republican |

| Pennsylvania | Politician | Bipartisan |

| Virginia | Hybrid | Bipartisan |

| Washington | Independent | — |

Eight states use independent commissions to draw state legislative districts. In Alaska, the governor appoints two individuals and the Speaker of the House, senate president, and Chief Justice of the Alaska Supreme Court each appoint one individual to the Redistricting Board. In Arizona, Montana, and Washington, the four legislative party leaders each appoint one member to the redistricting commission, and these four individuals choose a fifth member to chair the commission. California's Citizen's Redistricting Commission consists of five Democrats, five Republicans, and four individuals who are not members of either party. Idaho's Commission for Reapportionment consists of six individuals appointed by the chairmen of the two largest parties (based on the most recent gubernatorial vote) and the four state legislative party leaders.[27]

Six states use politician commissions to draw state legislative districts. Arkansas's Board of Apportionment consists of the governor, secretary of state, and attorney general. The Ohio Redistricting Commission consists of the governor, auditor, secretary of state, and four individuals appointed by the state legislative party leaders. Hawaii's Reapportionment Commission consists of eight appointees of the state legislative party leaders, and these appointees select a ninth member to chair the commission. The New Jersey Apportionment Commission consists of twelve individuals appointed by the state legislative party leaders and the two major party chairmen, with these twelve individuals choosing a thirteenth member to chair the board. Pennsylvania's redistricting commission consists of four appointees chosen by the state legislative party leaders, and these four appointees choose a fifth member to chair the commission. In Missouri, a commission is created for each legislative chamber as a result of the governor picking from lists submitted by the leaders of the two major parties.[27]

One state, Virginia, uses a hybrid, bipartisan commission consisting of eight legislators and eight non-legislator citizens. The commission is evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans.[22]

Final disposition

[edit]

- ^ Louisiana is labeled as Republican because the Democratic governor vetoed the maps but was overridden with almost no Democratic votes

- ^ Maryland is labeled as bipartisan because the Republican governor signed the Democratic-controlled legislature's maps after a court overturned a Democratic gerrymander as a deal to drop the legislature's appeal

This table shows the final status of redistricting in each state.

| State | U.S. House seats |

U.S. House disposition |

State legislative disposition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 52 | Passed into law on December 27, 2021[28] | Passed into law on December 27, 2021[28] | |

| 38 | Passed into law on October 25, 2021*[29] | Passed into law on October 25, 2021*[30] | |

| 28 | Passed into law on April 22, 2022*[31] | ||

| 26 | Passed into law on February 3, 2022;[32] Overturned on March 31, 2022[33] | Passed into law on February 3, 2022[32] | |

| 17 | Passed into law on February 23, 2022[34] | Passed into law on February 4, 2022[35] | |

| 17 | Passed into law on November 23, 2021[36] | Passed into law on September 24, 2021[37] | |

| 15 | Passed into law on November 20, 2021*;[38] Overturned by state Supreme Court on January 14, 2022[39] | Passed into law on September 16, 2021;[40] Overturned by state Supreme Court[41] | |

| 14 | Passed into law on December 30, 2021*[42] | Passed into law on December 30, 2021*[42] | |

| |

14 | Passed into law on February 23, 2022[43] | Passed into law on February 23, 2022[43] |

| 13 | Passed into law on December 28, 2021*[44] | Passed into law on December 28, 2021[45] | |

| 12 | Passed into law on December 22, 2021*[46] | Passed into law on February 18, 2022[47] | |

| 11 | Passed into law on December 28, 2021[48] | Passed into law on December 28, 2021[48] | |

| 10 | Passed into law on February 8, 2022[49] | Passed into law on February 8, 2022[50] | |

| 9 | Passed into law on December 22, 2021[51] | Passed into law on December 22, 2021[51] | |

| 9 | Passed into law on November 22, 2021[52] | Passed into law on November 4, 2021[53] | |

| 9 | Passed into law on February 6, 2022[54] | Passed into law on February 6, 2022[54] | |

| 9 | Passed into law on October 4, 2021[55] | Passed into law on October 4, 2021[55] | |

| 8 | Passed into law on April 4, 2022[56] | Passed into law on January 27, 2022*[57] | |

| 8 | Passed into law on May 18, 2022[58] | ||

| 8 | Passed into law on March 3, 2022[59] | Passed into law on March 3, 2022[60] | |

| 8 | Passed into law on November 1, 2021[61] | Passed into law on November 15, 2021[62] | |

| 8 | Passed into law on February 15, 2022[63] | Passed into law on February 15, 2022[64] | |

| |

7 | Passed into law on January 26, 2022*[65] | Passed into law on December 10, 2021[66] |

| 7 | Passed into law on November 4, 2021*[29] | Passed into law on November 4, 2021[67] | |

| 6 | Passed into law on March 30, 2022[68] | Passed into law on March 14, 2022[69] | |

| 6 | Passed into law on January 20, 2022*[70] | Passed into law on January 21, 2022[71] | |

| 6 | Passed into law on September 27, 2021[72] | Passed into law on September 27, 2021[72] | |

| 5 | Passed into law on November 22, 2021[73] | Passed into law on November 22, 2021[73] | |

| 5 | Passed into law on February 10, 2022[74] | Passed into law on November 23, 2021[75] | |

| 4 | Passed into law on November 12, 2021[76] | Passed into law on November 16, 2021[77] | |

| 4 | Passed into law on November 4, 2021[29] | Passed into law on November 4, 2021[78] | |

| 4 | Passed into law on November 16, 2021*[79] | Passed into law on November 16, 2021*[79] | |

| 4 | Passed into law on January 14, 2021[80] | Passed into law on November 29, 2021[81] | |

| 4 | Passed into law on January 25, 2022[82] | ||

| 4 | Passed into law on February 9, 2022*[83] | Passed into law on April 15, 2022[84] | |

| 3 | Passed into law on December 17, 2021*[85] | Passed into law on January 6, 2022*[86] | |

| 3 | Passed into law on September 30, 2021[87] | Passed into law on September 30, 2021[87] | |

| 2 | Passed into law on November 5, 2021[88] | Passed into law on November 5, 2021[88] | |

| 2 | Passed into law on October 22, 2021[29] | Passed into law on October 22, 2021[89] | |

| 2 | Passed into law on January 28, 2022[90] | Passed into law on January 28, 2022[91] | |

| 2 | Passed into law on May 31, 2022 [92] | ||

| 2 | Passed into law on September 29, 2021[93] | Passed into law on September 29, 2021[93] | |

| 2 | Passed into law on February 18, 2022[94] | Passed into law on February 18, 2022[94] | |

| 2 | Passed into law on November 12, 2021[95] | ||

| 1 | — | Passed into law on November 2, 2021[96] | |

| 1 | — | Passed into law on November 10, 2021[97] | |

| 1 | — | Passed into law on November 12, 2021*[98] | |

| 1 | — | Passed into law on November 10, 2021*[99] | |

| 1 | — | Passed into law on April 6, 2022[100] | |

| 1 | — | Passed into law on March 25, 2022[101] |

An * indicates that litigation is currently pending against the finalized maps

Litigation

[edit]Lawsuits have been filed against a number of passed congressional and legislative maps on the grounds of either racial gerrymandering or partisan gerrymandering. These states include Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina and Texas. As more states continue to adopt maps through the redistricting process, the number of lawsuits filed will potentially increase.[102]

Racial gerrymandering

[edit]Lawsuits have been filed in multiple states against congressional and state legislative maps due to claims that the new maps disenfranchise minority voters.

In Alabama, four lawsuits were filed against the congressional and state legislative maps, alleging racial bias and violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) by diluting the power of minority voters in the state.[103] On January 24, 2022, a three-judge panel blocked Alabama's congressional maps over claims it likely violates the VRA. The panel argued that because African Americans counted for a considerable percentage of the total population growth, there should be more opportunities for representation.[104][105] On February 7, 2022, the Supreme Court temporarily reinstated Alabama's congressional map and added Alabama's appeal to their 2022 case list, with the hearing date yet to be decided.[106] On June 8, 2023, the Supreme Court upheld the lower court's decision, ruling in Allen v. Milligan that Alabama did in fact illegally dilute the power of Black voters.[107] The Alabama Legislature defied the Supreme Court, drawing a map with only a single Black-majority district, rather than the ruling's minimum two districts.[108]

The NAACP and American Civil Liberties Union sued multiple state officials in Arkansas over the new state House districts, arguing that they unconstitutionally underrepresented Black voters.[109] A Trump appointed US District judge ruled that the groups did not have standing, and stated that the plaintiff must be the US Attorney General in February, 2022.[110] The ACLU appealed the ruling following the decision by the United States Department of Justice not to intervene.[111] US Senator Tom Cotton filed an amicus brief with the court supporting the state of Arkansas, calling racial gerrymandering accusations "baseless".[112] Two lawsuits were also filed against Arkansas's congressional districts, arguing that the map disenfranchised black voters by splitting Pulaski County between three congressional districts and moving 23,000 black voters out of Arkansas's 2nd congressional district.[113]

In Georgia, staff attorneys at the Southern Poverty Law Center claimed that, "the maps produced out of the special legislative session block Georgia's communities of color from obtaining political representation that reflects their population growth".[114] The American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia filed suit in December 2021, alleging that both state legislative maps and congressional maps violated the VRA.[115] Specifically, the 6th, 13th, and 14th congressional districts were challenged. In March 2022, Judge Steve C. Jones allowed Georgia's congressional and state legislative maps to take effect for the 2022 Georgia state elections even though he believed that it was likely "that certain aspects of the State's redistricting plans are unlawful." Despite this, he decided that overturning Georgia's maps so close to the May primary would prove overly disruptive.[116] Later, in October 2023, Judge Jones found that Georgia's maps did illegally discriminate against Black voters, ordering the state to create an additional majority-Black district. The state of Georgia is expected to appeal that decision, and it remains uncertain what maps will be used for the 2024 elections.[117][118]

Both congressional and state legislature maps drawn by the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission were challenged in court for violating the VRA by reducing the number of Black-majority districts in Detroit.[119] While supporters claim that this allows Black voters to elect more Black-aligned candidates across a larger number of districts, opponents argue that this dilutes the power of Black voters.[120] The lawsuit against both the state legislative districts and the congressional districts was dismissed on February 3, 2022, due to insufficient evidence that the redistricting commission needed to create the same number of Black-majority districts.[121]

In Texas, the League of United Latin American Citizens and others filed a lawsuit against congressional and state legislative maps after they had passed the state legislature, but before they had been signed into law. They argued that despite over 50% of Texas's population growth over the past ten years being due to Hispanic citizens, the maps not only failed to add new Hispanic majority districts, but also eliminated several existing districts, violating the Voting Rights Act.[122] Republican state legislators claim that the maps were drawn without taking race into account, and that their legal counsel had previously advised them that the maps were legal under federal law.[123] In December 2021, the Department of Justice also filed a lawsuit against Texas's new congressional and state house maps, arguing that they "were drawn with discriminatory intent".[124]

Partisan gerrymandering

[edit]In Maryland, new congressional maps were vetoed by Governor Larry Hogan for being "disgracefully gerrymandered", but the Maryland state legislature overrode his veto on December 9, 2021.[125] Subsequently, two Republican aligned groups sued to overturn the new congressional maps, arguing that they were partisan gerrymanders that "cracked" Republican voters across several districts, diluting their voting power.[126] Primaries in the state were delayed to July 19 due to the ongoing litigation.[127] On March 25, a circuit court judge threw out the congressional districts, calling them an "extreme gerrymander" that disenfranchised multiple communities of interest.[128]

New York's congressional, state assembly, and state senate districts were thrown out by a New York state judge on March 31, 2022, for violating a state Constitutional provision banning partisan gerrymandering.[33] On April 21, 2022, a New York appeals court upheld the ruling that New York's congressional maps were drawn with illegal partisan intent, but they reinstated the state assembly and state senate districts.[129] Upon a second appeal by the state Democratic party, The New York State Court of Appeals found that the congressional and state senate districts were "drawn with impermissible partisan purpose." As such, both maps were found unconstitutional, and Carnegie Mellon University post-doctoral fellow Jonathan Cervas was appointed as an independent special master to draw new maps.[130] Federal Judge Gary L. Sharpe of the Northern District of New York delayed New York's congressional and state senate primaries to August in May 2022, rejecting an argument from state Democrats that the primary must take place in June, and so it was too late to redraw new maps. He called the argument "a Hail Mary pass, the object of which is to take a long-shot try at having the New York primaries conducted on district lines that the state says is unconstitutional".[131]

The Supreme Court of Ohio overturned initially passed state legislative maps, arguing that they unfairly favored Republicans against the guidance of Ohio's 2015 redistricting amendment that seeks to limit partisan gerrymandering.[41]

The Republican Party of New Mexico sued to overturn the new congressional maps, arguing that they unduly favor Democrats and dilute Republican voting strength, thereby violating the equal protection clause of the New Mexico state constitution. New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham characterized the congressional map as one "in which no one party or candidate may claim any undue advantage."[132]

In February 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down both state legislative maps and the congressional map initially passed by the state legislature in November 2021, citing partisan gerrymandering that violated the state Constitution.[133] As a result, the North Carolina legislature drafted new maps, which they submitted to the court for approval.[134] A three-judge panel of the court upheld the legality of both state legislative maps, but had court-appointed special masters redraw the congressional map, which was released and approved in February 2022.[43]

Racial and partisan gerrymandering

[edit]Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP is the first partisan gerrymandering case taken by the United States Supreme Court after its landmark decision in Rucho v Common Cause which stated that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts, and the first racial gerrymandering case, after the court's landmark decision in Allen v Milligan.[135] The South Carolina case is pending a court decision in 2024.[136]

Court-run redistricting

[edit]State supreme courts have selected or drafted new congressional maps in Connecticut, Minnesota, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin following the failure of redistricting panels or lawmakers to pass new maps in each state.[citation needed]

The Connecticut Supreme Court was forced to take over the congressional redistricting process after the bipartisan legislative panel deadlocked and failed to agree on new maps. The court appointed Nathaniel Persily, who drew Connecticut's 2010 maps, as special master to draw the new congressional districts.[137] Persily drew a least-change map, making only the adjustments necessary to ensure equal population in each congressional district.[138] The court adopted Persily's recommended map on February 10, 2022.[74]

In North Carolina, local and state courts took over the congressional redistricting process in February 2022. After initial congressional and legislative maps were ruled as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders, several nonpartisan redistricting experts including Robert H. Edmunds Jr., Thomas W. Ross, and Robert F. Orr were appointed as special masters by the state Supreme Court. They were tasked with reviewing whether the second iteration of state legislative and congressional maps passed by the North Carolina legislature violated state Constitution provisions opposing partisan gerrymandering.[139] The special masters in coordination with the Wake County Superior Court found that the new congressional map was unconstitutional, and instead implemented their own map on February 23, 2022.[43] North Carolina House Speaker Tim Moore called the process "egregious" and "unconstitutional", and accused the court of drawing the maps "in an unknown, black-box manner".[140]

Following the failure of the Minnesota Legislature to pass either congressional or state legislative districts by the mandated February 5, 2022, deadline, the Minnesota Supreme Court appointed a five-member commission to draw new boundaries.[141] The panel released the state's new maps later in February.[64]

Redistricting organizations and funds

[edit]Democrats were particularly unhappy with the results of the 2012 House elections in which Democratic House candidates received more votes than Republican House candidates, but Republicans retained control of the chamber.[142] Organizations such as the Democratic Governors Association and the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee have established funds dedicated to helping Democrats in the 2020 round of redistricting.[142][143] Democrats also established the National Democratic Redistricting Committee to coordinate Democratic redistricting efforts.[144] Republicans established a similar group, the National Republican Redistricting Trust.[145]

Changes to the redistricting process between 2012 and 2022

[edit]Federal court rulings

[edit]In the 2013 case, Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court struck down Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act, which was a coverage formula that determined which states and counties required preclearance from the Justice Department before making changes to voting laws and procedures.[146] The formula had covered states with a history of minority voter disenfranchisement, and the preclearance procedure was designed to block discriminatory voting practices.[146] In the 2019 case of Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court held that claims of partisan gerrymandering present nonjusticiable political questions that cannot be reviewed by federal courts.[147]

In another 2019 case, Department of Commerce v. New York, the Supreme Court blocked the Trump administration from adding a question to the 2020 census regarding the citizenship of respondents.[148]

State court rulings

[edit]In 2015, the Supreme Court of Florida ordered the state to draw a new congressional map on the basis of a 2010 state constitutional amendment that banned partisan gerrymandering.[149]

In 2018, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court threw out the 2011 U.S. House of Representatives map on the grounds that it violated the state constitution; the court established new redistricting standards requiring districts to be compact and to minimize the splitting of counties and towns.[150]

In 2019, a North Carolina state court struck down the state's legislative districts on the grounds that the district had been created with the partisan intent of favoring Republican candidates.[151]

In 2022, the Ohio Supreme Court struck down the state's congressional and legislative districts multiple times.[152]

Ballot measures

[edit]In 2015, Ohio voters approved a ballot measure changing the composition of the commission charged with drawing state legislative districts, adding two legislative appointees to the commission and creating rules and guidelines designed to make partisan gerrymandering more difficult.[153] In May 2018, Ohio voters approved a proposal that modified the state's congressional redistricting processes.[12]

In 2018, voters in Colorado and Michigan approved of a proposal to establish an independent redistricting commission for congressional and state legislative districts in their respective states.[154] In Utah, voters approved the creation of a redistricting commission to draw congressional and state legislative districts, though the Utah state legislature retains the power to reject these maps.[155]

In 2020, voters in Virginia approved the establishment of a bipartisan redistricting commission for both congressional and state legislative redistricting. The commission consists of eight legislators and eight non-legislator citizens, with the commission split evenly between Democrats and Republicans.[22]

In 2018, Missouri voters approved of a proposal to have a non-partisan state demographer draw state legislative districts, but in 2020 Missouri voters approved a second referendum eliminating the state demographer position and restoring the system in place prior to the 2018 referendum.[156]

See also

[edit]- 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021 United States elections

- Gerrymandering in the United States

- Redistricting in the United States

- Electoral geography

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Several states, including Iowa,[7] New York,[8] and Utah,[9] employ commissions that play a role in the redistricting process. However, unlike in the states labeled as "independent commission" or "politician commission", in these states the legislature has the final power to approve redistricting maps.

References

[edit]- ^ Miller, pp. 10-11

- ^ Miller, William J.; Walling, Jeremy (June 7, 2013). The Political Battle over Congressional Redistricting. Lexington Books. pp. 1–4. ISBN 9780739169841. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ Wilson, Reid (February 4, 2015). "Nevada Republicans could take up mid-decade redistricting". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ 2020 Census Apportionment News Conference. United States Census Bureau. April 26, 2021.

- ^ Wasserman, David (April 26, 2021). "2020 Census: What the Reapportionment Numbers Mean". The Cook Political Report.

- ^ Skelley, Geoffrey; Rakich, Nathaniel (April 26, 2021). "Which States Won — And Lost — Seats In The 2020 Census?". FiveThirtyEight.

- ^ "Iowa". All About Redistricting. Justin Levitt.

- ^ "New York". All About Redistricting. Justin Levitt.

- ^ "Utah". All About Redistricting. Justin Levitt.

- ^ a b "Election Dates for Legislators and Governors Who Will Do Redistricting". National Conference of State Legislatures. May 25, 2018. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Levitt, Justin. "Who draws the lines?". Loyola Law School. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Wilson, Reid (May 8, 2018). "Ohio voters pass redistricting reform initiative". The Hill. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Haughey, John (November 14, 2016). "State-By-State Guide To Gubernatorial Veto Types". CQ Roll Call. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ a b Levitt, Justin; McDonald, Michael. "Taking the "Re" out of Redistricting: State Constitutional Provisions on Redistricting Timing" (PDF). The Georgetown Law Journal. 95 (4): 1247–1254. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ Schaller, Thomas (March 21, 2013). "Multi-Member Districts: Just a Thing of the Past?". Sabato's Crystal Ball. Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ a b Levitt, Justin. "Where are the lines drawn?". All About Redistricting. Loyola Law School. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Redistricting Criteria". National Conference of State Legislatures. January 26, 2016. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "2018 State & Legislative Partisan Composition" (PDF). NCSL. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "Party control - congressional lines". All About Redistricting. Justin Levitt. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ a b The number of U.S. representatives the state will have after the 2022 redistricting.

- ^ a b "Redistricting Commissions: Congressional Plans". National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ a b c Weiner, Rachel (November 4, 2020). "Virginians approve turning redistricting over to bipartisan commission". Washington Post.

- ^ Levitt, Justin. "Who draws the lines?". Loyola Law School. Archived from the original on December 4, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Goodman, Josh (July 7, 2011). "The Disappearance of Multi-Member Constituencies". Governing. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Moncrief, Gary F. (2011). Reapportionment and Redistricting in the West. Lexington Books. p. 30. ISBN 9780739167618. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "Party control - state legislative lines". All About Redistricting. Justin Levitt. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "Redistricting Commissions: State Legislative Plans". NCSL. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Larson, Elizabeth (December 28, 2021). "California Citizens Redistricting Commission delivers maps to California Secretary of State".

- ^ a b c d Coleman, J. Miles (November 11, 2011). "Less Than A Year Out: A Redistricting Update". University of Virginia.

- ^ Limon, Elvia (October 25, 2021). "Gov. Greg Abbott signs off on Texas' new political maps, which protect GOP majorities while diluting voices of voters of color". The Texas Tribune.

- ^ Fineout, Gary (April 22, 2022). "DeSantis signs new congressional map into law as groups sue over redistricting". Politico.

- ^ a b "Hochul signs new election maps into law". February 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Fandos, Nicholas (March 31, 2022). "Judge Tosses N.Y. District Lines, Citing Democrats' 'Bias'". The New York Times.

- ^ Lai, Jonathan; Tamari, Jonathan; Terruso, Julia (February 23, 2022). "The Pa. Supreme Court has picked a new congressional map". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Huangpu, Kate (February 4, 2022). "Final Pa. legislative maps approved by redistricting panel, but legal challenges likely". Spotlight Pennsylvania.

- ^ Navarro, Aaron (November 24, 2021). "Democrats add one more House seat in Illinois from redistricting, playing catch up with GOP". CBS News.

- ^ Hancock, Peter (January 4, 2022). "Three-judge federal court panel upholds state legislative redistricting plan". The State Journal Register.

- ^ "Ohio governor signs new congressional district map into law". ABC News.

- ^ Buchanan, Tyler (January 14, 2022). "Ohio Supreme Court strikes down GOP-drawn congressional map". Axios. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ Tebben, Susan (September 16, 2021). "Republican majority gerrymanders Ohio for another four years". Ohio Capital Journal.

- ^ a b Carr Smith, Julie (January 12, 2022). "Ohio justices toss GOP Statehouse maps, order fix in 10 days". The Associated Press. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Kemp Signs Into Law Georgia District Maps, 3 Lawsuits Follow". December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Wines, Michael (February 23, 2022). "North Carolina Court Imposes New District Map, Eliminating G.O.P. Edge". The New York Times.

- ^ "Michigan redistricting commission adopts final Congressional map". mlive. December 28, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Hendrickson, Clara. "Michigan redistricting commission adopts new state legislative maps". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Friedman, Matt (December 22, 2021). "Democrats prevail in New Jersey redistricting with map that could sacrifice Malinowski". Politico.

- ^ Biryukov, Nikita (February 18, 2022). "Democrats, GOP agree on new legislative map for N.J." New Jersey Monitor. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Vozzella, Laura. "Virginia Supreme Court approves redrawn congressional, General Assembly maps". Washington Post.

- ^ "Washington's Final Congressional Map Retains Two Swing Districts". February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "New political mapping concludes with revisions by lawmakers". Herald Net.

- ^ a b "AZ Republicans come out ahead in seats for Legislature, Congress as redistricting panel approves maps". December 22, 2021.

- ^ "Baker Signs Massachusetts' Congressional Redistricting Map". U.S. News & World Report. November 23, 2021. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ "Gov. Baker Signs Bills Creating New State House, Senate Districts". CBS Boston. November 7, 2021. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Gov. Bill Lee signs redistricting bills dividing Davidson County into three congressional districts". The Tennessean. February 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Lange, Kaitlin. "Gov. Holcomb signs Indiana's redistricting maps into law". The Indianapolis Star.

- ^ Flynn, Meagan; Wiggins, Ovetta. "Gov. Hogan signs new MD. congressional map into law, ending legal battles". The Washington post.

- ^ Leckrone, Bennett (January 27, 2022). "House of Delegates Gives Final Approval To Legislative Redistricting Plan". Maryland Matters.

- ^ Keller, Rudi (May 18, 2022). "Missouri Gov. Mike Parson signs new congressional redistricting plan". Missouri Independent. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ Brewster, Shaquille (March 3, 2022). "Wisconsin Supreme Court approves congressional map proposed by Democratic governor". NBC News.

- ^ Marley, Patrick (March 3, 2022). "Wisconsin Supreme Court picks Democratic Gov. Tony Evers' maps in redistricting fight". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ^ "Colorado Supreme Court approves new congressional map drawn by redistricting commission". The Colorado Sun. November 1, 2021.

- ^ Verlee, Megan (November 15, 2021). "Colorado officially has new state legislative maps". Colorado Public Radio.

- ^ Wilson, Reid. "Minnesota court makes changes to House Democrat's district". The Hill.

- ^ a b Salisbury, Bill. "New redistricting maps reshuffle Minnesota's political landscape". Twin Cities Pioneer Press.

- ^ "McMaster OKs controversial SC congressional map that protects GOP advantage". The State. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "McMaster signs off on SC House, Senate redistricting maps". The State. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Gov. Kay Ivey signs off on Alabama congressional, legislative, SBOE maps for 2022".

- ^ Muller, Wesley (March 30, 2022). "Louisiana Legislature overrides Gov. Edwards' veto of congressional maps". WDSU6 News. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Ballard, Mark (March 9, 2022). "Gov. John Bel Edwards vetoes proposed Congressional district map". The Advocate. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ "Ky. House, Senate quickly vote to override one of Beshear's vetoes on redistricting bills; budget on fast track". WKYT. January 19, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Rogers, Steve (January 21, 2022). "UPDATE: Beshear lets state Senate redistricting become law". ABC36 WTVQ.

- ^ a b Borrud, Hillary (September 27, 2021). "Oregon's redistricting maps official, after lawmakers pass them, Gov. Kate Brown signs off". oregonlive. Archived from the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt signs six redistricting bills into law". November 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Connecticut Supreme Court adopts expert's redistricting plan". Associated Press. February 11, 2022.

- ^ McQuaid, Hugh (November 23, 2021). "Redistricting Commission Tweaks Senate Map". CT News Junkie.

- ^ McKellar, Katie (November 12, 2021). "Utah Gov. Spencer Cox signs off on controversial congressional map that 'cracks' Salt Lake County". Deseret News.

- ^ Rodgers, Bethany (November 16, 2021). "Gov. Cox signs bill exempting certain employees from workplace COVID-19 vaccine mandates". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- ^ "Gov. Kim Reynolds signs Iowa's new redistricting maps into law". Des Moines Register. November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b "Nevada redistricting bill signed by Sisolak after split Assembly vote". The Nevada Independent. November 16, 2021.

- ^ Kronaizl, Douglas (January 17, 2022). "Arkansas' congressional map goes into effect". Ballotpedia News.

- ^ DeMillo, Andrew (November 29, 2021). "Arkansas panel approves new state House, Senate districts". Associated Press.

- ^ "Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves signs bill for congressional redistricting map". Clarion Ledger. January 25, 2022.

- ^ Carpenter, Tim (February 9, 2022). "Kansas House completes override of Gov. Kelly's veto of congressional redistricting map". Kansas Reflector.

- ^ Bahl, Andrew; Garcia, Rafael (April 15, 2022). "Kansas governor signs new legislative, board of education maps, with legal challenge possible". The Topeka Capital-Journal.

- ^ "Governor signs congressional redistricting bill". The Las Cruces Bulletin. December 21, 2021.

- ^ Sanchez Saturno, Luis (January 7, 2022). "Governor signs contentious redistricting bill". Santa Fe New Mexican.

- ^ a b "Nebraska's Governor signs redistricting bills into law". KETV. September 30, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "Idaho's final redistricting maps approved". Idaho Reports. November 5, 2021.

- ^ "Justice signs 40 bills from special session for redistricting, COVID vaccine measures". Charleston Gazette-Mail. October 25, 2021.

- ^ "Hawaii Commission Adopts Congressional Map With Tiny Changes". Bloomberg Government. January 28, 2022.

- ^ "Hawaii Reapportionment Commission Approves Final Legislative Maps". Honolulu Civil Beat. January 28, 2022.

- ^ Ramer, Holly (May 31, 2022). "New Hampshire court adopts congressional redistricting map". The Boston Globe. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Thousands of Mainers to shift to new congressional districts". September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b King, Ryan (February 18, 2022). "Rhode Island governor approves congressional map, creating opportunity for Republicans". Washington Examiner.

- ^ "After an amendment, Montana adopts final congressional map". Montana Public Radio. November 13, 2021.

- ^ Kronaizl, Douglas (November 16, 2021). "A closer look at Delaware's new state legislative maps". Ballotpedia News.

- ^ Goss, Austin (November 10, 2021). "South Dakota lawmakers compromise on redistricting map in special session". Fox Dakota News Now.

- ^ "Burgum Signs Legislative Redistricting Bill Passed This Week". Associated Press. November 12, 2021.

- ^ Kitchenman, Andrew (November 10, 2021). "Alaska Redistricting Board finishes work to adopt maps; opponents say courts could toss out portions". ktoo.org.

- ^ Mearhoff, Sarah (April 6, 2022). "Scott signs new legislative maps into law, solidifying Vermont's political playing field for next decade". VT Digger.

- ^ Eavis, Victoria (March 25, 2022). "Gov. Mark Gordon allows redistricting bill to become law without his signature". Casper Star Tribune.

- ^ Best, Ryan; Bycoffe, Aaron (August 9, 2021). "What Redistricting Looks Like In Every State". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Chandler, Kim (September 28, 2021). "Lawsuit: Alabama congressional map 'racially gerrymandered'". Associated Press. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Chandler, Kim (January 25, 2022). "Alabama's new congressional districts map blocked by judges". Associated Press. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ "Alabama's new congressional map blocked by judges". Politico. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (February 7, 2022). "Supreme Court, in 5-4 Vote, Restores Alabama's Congressional Voting Map". The New York Times. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 8, 2023). "Supreme Court Rejects Voting Map That Diluted Black Voters' Power". The New York Times.

- ^ "Alabama lawmakers refuse to create 2nd majority-Black congressional district". AP News. July 21, 2023. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Tarinelli, Ryan (December 29, 2021). "ACLU sues over state House redistricting map, says plan under-represents Black Arkansans". Arkansas Democrat Gazette. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Earley, Neal (February 19, 2022). "ACLU's next move on Arkansas redistricting lawsuit depends on Justice Department, group says". Arkansas Democrat Gazette. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Scott, Emily. "ACLU Appealing Dismissal of Challenge to AR Redistricting Map". Public News Service. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Ellis, Dale; Tarinelli, Ryan. "Cotton calls racial gerrymandering claims 'baseless,' urges court to dismiss part of Arkansas congressional map lawsuit". Arkansas Democrat Gazette. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ "2nd Lawsuit Filed Over Arkansas Congressional Redistricting". US News. March 22, 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ Niesse, Mark. "Lawsuits will challenge Georgia's new maps that favor Republicans". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Ashley, Asia (January 5, 2022). "Kemp signs redistricting maps, lawsuit filed". Valdosta Daily Times. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Brumback, Kate (March 2022). "Judge allows new Georgia political maps to be used this year". The Associated Press. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ Gringlas, Sam (October 26, 2023). "A federal judge says Georgia's political maps must be redrawn for the 2024 election". NPR.

- ^ Niesse, Mark; Prabhu, Maya T. (October 26, 2023). "BREAKING: Judge throws out Georgia's redistricting, orders new maps". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ Dwyer, Devin. "Michigan's 'fairer' election maps challenged for 'diluting' Black vote". ABC News. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Hendrickson, Clara. "Lawsuit filed against Michigan redistricting commission alleges maps unfair to Black voters". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Hendrickson, Clara. "Mich. Supreme Court upholds redistricting commission maps in face of voting rights lawsuit". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Ura, Alexa (October 19, 2021). "First lawsuit filed challenging new Texas political maps as intentionally discriminatory". Texas Tribune. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ Ura, Alexa (November 3, 2021). "Texas' new House map challenged in state court, expanding redistricting fight". Texas Tribune. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ Lucas, Ryan. "The Justice Department is suing Texas over the state's redistricting plans". NPR. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ Flynn, Meagan; Wiggins, Ovetta (December 9, 2021). "Maryland General Assembly overrides Hogan's veto of new congressional map". The Washington Post.

- ^ Leckrone, Bennett (December 23, 2021). "Second lawsuit filed over Maryland's new congressional districting map". WTOP News. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ Montellaro, Zach (March 15, 2022). "Maryland primary pushed back 3 weeks over redistricting challenge". Politico. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Corasaniti, Nick (March 25, 2022). "Judge Throws Out Maryland Congressional Map, in Blow to Democrats". The New York Times. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ Fandos, Nicholas (April 21, 2022). "N.Y. House Districts Illegally Favor Democrats, Appeals Court Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ Fandos, Nicholas (April 27, 2022). "Democrats Lose Control of N.Y. Election Maps, as Top Court Rejects Appeal". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ Fandos, Nicholas (May 10, 2022). "Federal Judge Dashes Democrats' Hopes for N.Y. District Maps". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ "Republican Party files legal challenge to New Mexico's recently approved political maps". Las Cruces Sun News. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Robertson, Gary (February 4, 2022). "North Carolina Supreme Court strikes down redistricting maps". Associated Press. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Robertson, Gary (February 20, 2022). "North Carolina lawmakers drew new political maps — again — that will now go back to court". WFAE 90.7. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "Takeaways from Supreme Court Arguments Over South Carolina's Congressional Map". Democracy Docket. October 11, 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (October 11, 2023). "Justices Poised to Restore Voting Map Ruled a Racial Gerrymander". The New York Times. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- ^ Haigh, Susan (December 24, 2021). "High Court Again Taps Election Law Expert to Redraw Lines". NBC Connecticut. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Pazniokas, Mark (January 18, 2022). "Special master recommends tweaks to Connecticut congressional map". The CT Mirror. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Doyle, Steve (February 17, 2022). "NC redistricting special masters have Greensboro flavor". Fox 8 News. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Bryan (February 23, 2022). "NC court enacts new legislative, congressional maps; GOP and voting group to appeal". WRAL. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Callaghan, Peter (February 11, 2022). "Off the map: Minnesota Legislature takes a pass on trying to come up with its own redistricting plan". Minn Post. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Levitz, Eric (August 4, 2015). "Democrats aim to 'unrig' congressional maps in 2020". MSNBC. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Sarlin, Benjy (August 26, 2014). "Forget 2016: Democrats already have a plan for 2020". MSNBC. Archived from the original on October 28, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Dovere, Edward-Isaac (October 17, 2016). "Obama, Holder to lead post-Trump redistricting campaign". Politico. Archived from the original on November 2, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Connolly, Griffin (September 29, 2017). "Republican Group Ready to Spend Big on Redistricting". Roll Call. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Levitt, Justin. "Who draws the lines?-Preclearance". All About Redistricting. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Chung, Andrew; Hurley, Lawrence (June 27, 2019). "In major elections ruling, U.S. Supreme Court allows partisan map drawing". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 27, 2019). "Supreme Court Leaves Census Question on Citizenship in Doubt". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ Prokop, Andrew (December 5, 2015). "Florida's Supreme Court has struck another blow against gerrymandering". Vox. Archived from the original on November 24, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ Lai, Jonathan; Navratil, Liz. "Pennsylvania, gerrymandered: A guide to Pa.'s congressional map redistricting fight". Philly.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Mills Rodrigo, Chris (September 3, 2019). "North Carolina court strikes down state legislative map". The Hill. Archived from the original on September 5, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Trevas, Dan (July 19, 2022). "Court Invalidates Second Congressional Map". Court News Ohio. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ Siegel, Jim (November 4, 2015). "Voters approve issue to reform Ohio's redistricting process". The Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ Moon, Emily (November 7, 2018). "How Did Citizen-Led Redistricting Initiatives Fare in the Mid-Terms?". Pacific Standard. Archived from the original on November 7, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Rodgers, Bethany; Wood, Benjamin (February 22, 2020). "Utah's new anti-gerrymandering law is at risk, group warns". The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ Lieb, David A. (November 5, 2020). "Missouri voters dump never-used redistricting reforms". AP.

External links

[edit]- "50 State Guide to Redistricting". Brennan Center for Justice. Archived from the original on August 26, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- "The Atlas of Redistricting". FiveThirtyEight. January 25, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.