19th century glassmaking in the United States

Boston and Sandwich Glass Co.,

Metropolitan Museum of Art

19th century glassmaking in the United States started slowly with less than a dozen glass factories operating. Much of the nation's better quality glass was imported, and English glassmakers had a monopoly on major ingredients for high–quality glass such as good–quality sand and red lead. A tariff and the War of 1812 added to the difficulties of making crystal glass in America. After the war, English glassmakers began dumping low priced glassware in the United States, which caused some glass works to go out of business. A protective tariff and the ingenuity of Boston businessman Deming Jarves helped revive the domestic glass industry.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase added western territory to the United States and eventually opened new markets for glass products. Glass works located along the Ohio River in Pittsburgh and Wheeling were able to take advantage of the nation's waterways to ship their products. Most of the growth of the nation's railroad industry occurred in the second half of the century, which provided an alternative to waterways for transportation. Coal, as an alternative to wood to power the glassmaking furnaces, was another factor that lured glassmakers away from the nation's east coast. By mid-century these factors, along with deforestation in the east, shifted glassmaking away from the east coast to western regions near Pittsburgh and West Virginia. The discovery of natural gas in Ohio and Indiana caused gas booms in those regions, but those sources of low-cost fuel were mismanaged and then depleted.

Two major discoveries transformed 19th century glassmaking in the United States. The use of a machine to press glass was developed in the 1820s, leading to more efficient production. A formula for soda–lime glass was discovered in the 1860s. This formula, which is probably similar to the long–lost formula used by Europeans centuries earlier, enabled the production of high–quality glass at a lower cost. This led to mechanical innovations throughout the second half of the century, such as better furnaces for melting the raw materials and better methods of cooling the glass. By the end of the century, research was being conducted that would make substantial changes to the way bottles and window glass were produced.

Glassmaking

[edit]

Glassmakers use the term "batch" for the sum of all the raw ingredients needed to make a particular glass product.[1] To make glass, the glassmaker starts with the batch, melts it together, forms the glass product, and gradually cools it. The batch is dominated by sand, which contains silica. Smaller quantities of other ingredients, such as soda and limestone, are added to the batch.[2] Additional ingredients may be added to color the glass. For example, an oxide of cobalt is used to make glass blue.[3] Broken and scrap glass, known as cullet, is often used as an ingredient to make new glass. The cullet melts faster than the other ingredients, which results in some savings in fuel cost for the furnace. Cullet can account for 25 to 50 percent of the batch.[4]

The batch is placed inside a pot or tank that is heated by a furnace to roughly 3,090 °F (1,700 °C).[2] Tank furnaces, which were created in England in 1870, did not began to supplant pot furnaces in the United States until the 1890s.[5] Glassmakers use the term "metal" to describe batch that has been melted together.[6] The metal is typically shaped into the glass product (other than plate and window glass) by either glassblowing or pressing it into a mold.[7] Although pressing glass by hand has long existed, mechanical pressing of glass did not exist until the 1820s—and it was an American invention.[8] In some cases, the glass is cut and polished, engraved, etched, or enameled.[9] All glass products must be cooled gradually (annealed), or else they could easily break.[10] Annealing was originally conducted in the United States using a kiln that was sealed with the fresh glass inside, heated, and gradually cooled.[11] During the 1860s annealing kilns were replaced in the United States with conveyor ovens, called lehrs, that were less labor-intensive.[12]

Labor, fuel and transportation

[edit]

Labor was the biggest expense for manufacturers of glass.[13] Germans dominated American glassmaking until the 19th century.[14] Glassmaking methods and recipes were kept secret, and most European countries forbid immigration to the United States by glassworkers.[15][Note 1] Some of the skilled glassworkers were smuggled from Europe to the United States.[15] Glass company financiers discovered that if a skilled glass worker left their company, glassmaking knowledge left with them.[17] Boston businessman Deming Jarves, who has been called the "father of the American glass industry", joined the industry in 1809 as an investor.[18] Jarves began to keep a book of glass recipes. He learned from the glassmakers he hired, and he conducted his own experiments. He also pursued knowledge about the process for melting the batch and annealing the glass. This corporate practice eliminated the risk of a skilled glassmaker leaving the company and taking know–how with him.[17]

The second largest expense for glassmaking is fuel for the furnace, and fuel availability often determined the location of a glass works.[19] Wood was the original fuel used by glassmakers in the United States. Coal began being used in the 1790s.[20] The problem with wood was that, in good times, a glass factory could consume an amount of forest equal in size to an American football field—in one week.[21] By 1850, glassmaking in the United States had shifted from the east coast to Pittsburgh and West Virginia because of the availability of coal and deforestation in the east.[22] Alternative fuels such as natural gas and oil did not become available in the United States until the 1870s when they were discovered in Pennsylvania and West Virginia.[23] In the 1880s, the discovery of natural gas in northwest Ohio combined with its railroad facilities to cause numerous glass factories to relocate there.[22] A similar gas boom followed in East Central Indiana. The gas field in Indiana was larger than the Ohio and Pennsylvania gas fields combined.[24] Among the larger and more famous factories started was the Muncie, Indiana, glass works of the Ball brothers—makers of the Ball mason jar.[25] Northwestern Ohio's gas boom faded as gas supply problems began around 1891.[26] The Indiana Gas Boom was over by 1901, as gas pressure fell because of waste and mismanagement of a resource that many believed would last for decades.[27]

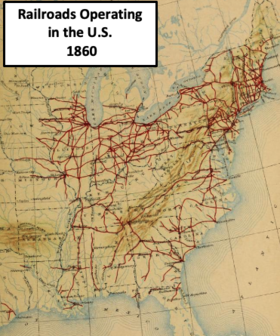

Transportation is another important factor for glassmaking.[28] When Edward Libbey moved New England Glass Company in 1888, transportation resources were a major factor in his selection of Toledo, Ohio.[29] Toledo had access to the Great Lakes, the Miami and Erie Canal that connected with the Ohio River, and numerous railroad lines.[30] Waterways had provided transportation networks for the glass factories long before the construction of highways and railroads.[31] The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 opened new markets to glass factories, and those situated on the Ohio River had a waterway to ship their products.[32] The introduction of steamboats to the western United States in 1811 made upriver transportation easier.[33] Construction of the National Road began in 1811 in Cumberland, Maryland. The road, the nation's first federally–funded highway, reached Wheeling by 1818 and Illinois by the 1830s.[34] The first commercial railroad in the United States was not chartered until 1827, and construction began in 1828.[35] Pittsburgh and Wheeling had railroad service by the early 1850s, causing a decline in the use of the National Road.[36] By June 30, 1900, the United States had over 193,000 miles (311,000 km) of rail line and over 1,200 railroads operating.[37]

Beginning of the century

[edit]England

[edit]In 1800, the United States was thought to have no more than ten glass factories operating.[38] Most of these factories produced window glass or bottles made of green glass, and very little high quality glassware was made.[39] The production of higher quality glass was limited by a lack of skilled glassblowers and lack of a necessary additive to the batch.[18] Most of the glass products in the United States were imported from England, and England controlled the supply of a necessary batch additive for crystal—red lead. The U.S. Embargo Act of 1807, and then the War of 1812, made it nearly impossible for American companies to acquire red lead.[40]

The War of 1812 also made it difficult to acquire good quality sand, since British ships brought the only good quality sand to the United States from the island of Demerara. After the war, England began dumping low–priced glass products in the United States while keeping its price for red lead high.[41] The introduction of the steamboat in the United States enabled imports to move from the port of New Orleans up the Mississippi River to the western markets of the United States.[42] The British/English competition caused some American glass factories, including Boston Crown Glass Company, to go into bankruptcy.[41][Note 2]

Jarves and Bakewell

[edit]

New England Glass Co.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bakewell, Page & Bakewell

Metropolitan Museum of Art

In response to the red lead problem, American glass man Deming Jarves, one of the owners of the failed Boston Crown Glass Company, developed a way to produce red lead from domestic sources of lead oxide. He was producing significant quantities of red led by 1819.[44] Good quality sand was found in the United States in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, in the Monongahela River in Pennsylvania, and in New Jersey.[41] In 1820, there were only 33 glassmaking facilities in the United States.[38] The Tariff of 1824, which was a protective tariff, helped the American glass industry. Between 1820 and 1840, nearly 70 glass factories were started in the United States. Most of these factories were small businesses employing 25 to 40 workers.[38] Jarves' New England Glass Company, incorporated in 1818, was exporting cut crystal glassware to Europe by 1825. His skilled workers were English and German immigrants, and he smuggled Belgian workers to his glass works because of their glass cutting expertise.[45]

A company originally known as Bakewell & Ensell was founded in 1808 in what was then the western United States. This company, which changed its name multiple times, became Pittsburgh's best known glass manufacturer.[46][Note 3] Deming Jarves considered founder Benjamin Bakewell the "father of the flint–glass [crystal] business in this country".[47] Like Jarves, Bakewell relied on skilled glassworkers that he smuggled to the United States. In Bakewell's case many of these glassworkers were from England.[48] The company was "gasping for breath" during a difficult period from 1817 until 1822, but produced glass for over 70 years.[49] In the 1820s and 1830s, Bakewell glassware was purchased for the White House by presidents James Monroe and Andrew Jackson.[46]

Pressed glass

[edit]In 1825, John P. Bakewell patented a pressing method for making glass furniture knobs.[50] Elsewhere other glass men were also working on mechanical pressing of glass. Henry Whitney and Enoch Robinson of New England Glass Company received a pressing–related patent in 1826; and Phineas C. Dummer, George Dummer, and James Maxwell of the Jersey City Glass Works received pressing and mold–related patents in 1827.[50] One historian has called the increased production rate caused by the mechanical pressing machine "the greatest contribution of America to glassmaking, and the most important development since the Romans discovered glassblowing".[51]

Glass had been pressed since the 1st century, but mechanical pressing was a technological advancement that lowered costs. It enabled skilled glassworkers to be replaced by unskilled workers that were more productive. A greater variety of glassware became available, and the lower costs enabled a larger segment of the public to afford lower–priced glassware.[52] New England Glass Company and Jarves' new Boston and Sandwich Glass Company (founded in 1825) were the early users of machine pressed glass technology to produce large quantities of glass.[53] Bakewell, Page & Bakewell was among the numerous glass works to produce pressed glass shortly afterwards.[50]

Railroads begin

[edit]Transportation resources for all manufacturers began to improve during this time, as the American railroad industry began construction of railroad line.[35] The first commercial railway, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, began work in 1828 to connect Baltimore's harbor with the Ohio River.[54] Its first segment of track was 13 miles (21 km) long, and it opened in 1830. This segment connected Baltimore to Ellicott's Mills in Maryland (now Ellicott City).[54] By 1835 the nation had over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of railroad line as other railroads constructed line, and by 1840 this improved to 2,818 miles (4,535 km).[55] In 1852 the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line reached the Ohio River at Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia).[54]

Mid–century

[edit]

Glassmaking on the East Coast of the United States peaked around 1850, as plants shifted to Pittsburgh because of the availability of coal for fuel.[56] By 1850, the United States had 3,237 free men above age 15 who listed their occupation as part of the glass manufacturing process.[57] Pennsylvania accounted for 40% of the glassmaking employees. Other states with more than 100 glass workers were New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, and Virginia (including what is now West Virginia).[57] The availability of rail transportation increased substantially at this time, as the nation's rail network consisted of over 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of rail line in 1850 and over 30,000 miles (48,000 km) by 1860.[58]

Pittsburgh

[edit]Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, had an early transportation advantage with the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers converging to form the Ohio River.[59] It also had good access to coal and high–quality sand.[60] In 1837, Pittsburgh had 15 glass works, and the nearby Pennsylvania counties of Fayette and Washington had 13 more.[61] By mid–century, Pittsburgh was the nation's new glassmaking center, and it had as many as 33 glass works by 1857. Nine of those factories made flint glass (crystal). The remaining factories made products such as bottles and window glass.[62][Note 4] The best known Pittsburgh glass company was Bakewell, Pears and Company. The company was known for its crystal, including cut and engraved glassware. It also made window glass, bottles, and lamps.[64]

Glass formula

[edit]

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Two former supervisors from the New England Glass Company, James B. Barnes and John L. Hobbs, founded Barnes, Hobbs and Company in 1845. Their glass factory, called the South Wheeling Glass Works, was located near a coal mine on the south side of Wheeling, Virginia (later West Virginia).[65] Their company was named J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company from 1863 to 1881, which includes the year the company developed a new formula for glass that changed the glassware business.[66][Note 5] The company produced all types of glassware, but did not make window glass or bottles. Products ranged from ordinary items such as kerosene lamps to art glass valued by collectors.[70] By 1879 the South Wheeling Glass Works was the largest glass factory in the United States. Three major innovations made by this company were the use of benzine in the polishing furnace, chilling molds using cold air, and a new formula for lime (soda–lime) glass.[71]

In 1863 William Leighton Sr and his son, William Leighton Jr, left the New England Glass Company to join J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company. The elder Leighton became the company chemist. In 1864 he developed an improved formula for soda–lime glass that could be pressed and did not require lead—but produced glass with almost the same quality as crystal.[66] The raw materials for this type of glass cost much less than crystal made with lead, and the soda–lime glass hardened faster. This made it necessary for workmen to shape the glass quicker, and encouraged innovation in shaping the glass. The result of these changes caused glassware to cost about one fourth of its earlier cost, and this caused retail prices for glassware to decrease. The lower costs led to glassware factories switching from lead crystal glass to soda–lime glass, more of the public being able to afford high–quality glassware, and more factories being built to meet demand.[72][Note 6]

End of the century

[edit]By 1880, 211 glassmaking factories existed in the United States, and they provided employment for 24,177 people.[75] Of the 211 factories, 169 produced during the year, while the remaining were either idle or under construction.[76] Glassware was produced by 73 of these factories, while 49 made window glass. Green glass was produced at 42 factories, and plate glass was made at five glass works.[76] Based on the value of the glass produced, Pennsylvania accounted for 41 percent of production, while New Jersey accounted for 13 percent.[77][Note 7] At a more local level, the Pennsylvania counties of Allegheny and Philadelphia accounted for almost 27 percent and almost eight percent of production, respectively.[78] Other glassmaking centers, in order of market share, were: Kings County, New York; Cumberland County, New Jersey; Gloucester County, New Jersey; Belmont County, Ohio; Ohio County, West Virginia; and Floyd County, Indiana. This group of counties had shares of the value of glass production that ranged from 6.24 to 3.07 percent.[78] Although glass was made in numerous other places, only five additional counties had a market share above two percent.[78]

Gas boom

[edit]

The discovery of natural gas in Ohio and Indiana caused glass factories to either move operations to this source of cheap fuel or begin new companies. Although natural gas had been discovered near Findlay, Ohio, in 1884, the Karg well changed outlooks two years later. The Karg well was located in the middle of Findlay, and the flame from this well could be seen over 40 miles (64 km) away in Toledo.[79] A decade earlier, natural gas fields had been discovered in West Virginia and near Pittsburgh. In addition to being a lower cost fuel for glass melting furnaces, it was cleaner and provided more heat. Communities such as Findlay, Fostoria, North Baltimore, Tiffin, and Toledo offered free gas as an incentive for manufacturers to relocate. Over 100 glass companies moved to (or started in) northwest Ohio to take advantage of gas from Findlay's gas field and a smaller one nearby in North Baltimore.[22] The gas supply lasted for only five years, causing most of the glass companies to move closer to better sources of fuel.[80] Examples of companies that relocated are Fostoria Glass Company, which moved from Fostoria to Moundsville, West Virginia; and Sneath Glass Company, which moved from Tiffin to Hartford City, Indiana.[81]

Natural gas was first discovered in Indiana in Pulaski County in 1865. The drillers were searching for oil, but found only gas. Unaware of the usefulness of natural gas, the drillers abandoned the well.[82] A more significant discovery was made in the small East Central Indiana community of Eaton, Indiana. This well was bored in 1876 to a depth of 600 feet (180 m), and the drillers were searching for coal. When they instead found gas that gave a flame two feet (0.61 m) high, the well was ignored.[82] In 1886, after hearing about the gas boom in Ohio, the Eaton well was re–drilled. Gas was discovered at a depth of 922 feet (281 m), and flames about ten feet (3.0 m) high rose from four pipes in the well.[83] More wells were drilled, and gas was found in significant quantities in 17 Indiana counties.[84] The Indiana gas field was the largest in the world, and it was larger than those of Pennsylvania and Ohio combined.[24] Indiana had its own gas boom, and East Central Indiana changed from an "agricultural district" to industrial. Glassmaking was one of the industries that moved to Indiana. In 1880, the state ranked eighth in glass production. By 1890, it ranked fourth. In terms of the number of glass factories, the state had four in 1880 and 21 in 1890.[85] By 1895, there were 50 glass factories in Indiana.[86] The state also benefitted from excellent railroad facilities and a coal field not far away from the gas belt. This enabled some factories to remain in Indiana after the gas supply became depleted.[86] The citizens of Indiana did not learn from their Ohio neighbors, and they wasted gas despite warnings from the state geologist. The Indiana Gas Boom was over by 1901.[27]

Libbey and Owens

[edit]

In 1888 Edward Libbey moved the New England Glass Company from East Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Toledo, Ohio.[87] Among new hires in late 1888 was glassblower Michael Joseph Owens, a former worker at the glass works of J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company who wanted to be a foreman.[88][Note 8] In 1892 the company changed its name to Libbey Glass Company.[87] Owens (1859–1923) received 49 patents and brought automation to the glass industry.[90] During the early 1890s, he created a machine that would blow light bulbs into molds. His process was more profitable and required fewer skilled laborers.[91]

In 1898 Owens began work on an automatic bottle machine. Newer versions of his bottle machine were created, and over 330 machines produced between 1908 and 1927.[91] His bottle machine could produce 24 bottles per minute, compared to a glassblower producing one per minute.[92] This higher production rate, with standardized shapes and sizes, changed the food, beverage, and pharmaceutical industries by making it possible for those industries to mechanize their capacity for filling the glass product. Things such as milk bottles, beer bottles, fruit jars, and other glass items became common because they could be produced at lower costs.[93] Later Owens teamed with Irving Wightman Colburn to create a radically different way to produce window glass, which became known as the Colburn process. This process was first used in 1917.[94]

Child labor

[edit]

Child labor has been described as a "scourge of the late 19th century".[95] The three largest industrial employers of children were coal mines, glass factories, and textile mills. Leaders in the glassmaking industry described the employment of children, some as young as 10 years old, as essential for certain tasks—and they were cheap labor.[95] About 20 to 45 percent of laborers at glass factories were children, and some were aged eight to twelve. They typically moved items, cleaned, and helped with the annealing process. They were also involved with packaging glassware.[96][Note 9] One of the few states that had laws protecting children was Ohio, which banned children under the age of 12 from working in a factory. Ohio also prohibited work in excess of ten hours per day for children who were old enough to work.[98]

New machinery, plus new regulations, led to a decline in the use of child labor during the last decade of the 19th century and the early 20th century. Of the approximately 19,000 workers added to the glassmaking industry between 1890 and 1905, 18,000 were adult men. Many of these new workers were immigrants. Belgium, England, France, and Germany typically contributed skilled workers—while immigrants from other countries were usually used for the lowest-paying jobs.[99] A by-product of the new wave of automation was the reduced need for child laborers. Owens' invention of an automated mold for the production of light bulbs eliminated the need for mold boys in light bulb production.[100] The John H. Lubbers glass blowing machine (machine drawn window glass) eliminated the need for glassblowers in the window glass making process.[99] Owens' bottle machine contributed to a reduction in child labor in two ways. In addition to the labor savings from using a machine to make bottles, the uniformity in the size of the bottles made possible the development of high-speed packing and filling lines that also provided labor savings. The National Child Labor Committee of New York commended the Owens machine, in 1913, for its role in eliminating child labor.[92]

Economics and glass trusts

[edit]

The end of the 19th century, despite the many glassmaking innovations, was difficult for many manufacturing companies. The U.S. economy suffered through six recessions during the 1880s and 1890s, making life difficult for manufacturing firms.[101] Three banking panics occurred during this period: the Panic of 1884, the Panic of 1890, and the Panic of 1893—which was one of the most severe in the nation's history.[102] Estimates of the unemployment rate for 1890 through 1900 show five or six years (depending on whose estimates are used) of double-digit unemployment.[103] From 1880 to 1900, consumer prices in the United States decreased nearly 14 percent, and changes for any year were either a decrease or no change.[104][Note 10] Adding to the glass companies' challenges was the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894, which caused glass imports to increase 48 percent.[105] Several years later, the Dingley Tariff of 1897 countered some of the competition from imports caused by the Wilson-Gorman tariff.[106]

Cost cutting was done because of necessity, as manufacturers fought to survive. In the glass industry, several trusts were formed in attempts to cut costs, control supply, and control prices. Among the trusts were the National Glass Company, United States Glass Company, and American Window Glass Company.[107] The United States Glass Company consisted of 16 tableware companies by 1893.[105] The National Glass Company controlled 19 glass companies, which meant it controlled about 75 percent of the glass tableware market in the United States.[106] The American Window Glass Company trust was created in 1898, and it had over half of the nation's window glassmaking capacity in part because it consisted of many of the large works that used tank furnaces.[108]

1899 summary

[edit]In 1899 the United States had 355 glass works and 55,256 employees. Leading states based on total production value were Pennsylvania (39%), Indiana (26%), New Jersey (9%) and Ohio (8%).[109] Based on the value of production of building glass (window, plate, and wire glass), Pennsylvania had the highest output in the nation. Indiana was second in this category, and its production was more than double all the other states (not including Pennsylvania) combined.[110] Pennsylvania was the leader in pressed and blown glass, followed by Ohio, Indiana, West Virginia, and New York. The leader for bottles and jars was Indiana, followed by New Jersey and Pennsylvania.[111] Bottles and jars accounted for 38 percent of all glass made during the year, based on value.[112] Pressed and blown glass, and building glass, each accounted for 30 percent of glass manufactured. (Rounding and an "all other" category account for the remaining two percentage points.) About two thirds of building glass was window glass.[112]

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Beginning in 1292, Venice moved its glassmaking industry, glassworks and glassmakers, to the Island of Murano. Leaving Murano, or revealing glassmaking secrets to foreigners, without permission was punishable by death.[16]

- ^ Boston Crown Glass Company, established near the end of the 18th century, was the first American window glass company of importance.[43]

- ^ Pittsburgh's Bakewell glass works had nine different names. From 1808 to 1809 it was named Bakewell & Ensell; and from 1809 to 1813 it was named Benjamin Bakewell & Company. From 1813 to 1827 it was named Bakewell, Page & Bakewell; and from 1827 to 1832 it was named Bakewell, Page & Bakewells. From 1832 to 1836 it was named Bakewells & Anderson; and from 1836 to 1842 it was named Bakewells & Company. The Pears family became involved and the company was named Bakewell & Pears from 1842 to 1844; Bakewell, Pears & Company from 1844 to 1880; and Bakewell, Pears Company, Ltd. from 1880 to 1882.[46]

- ^ An 1884 report by Joseph D. Weeks and the Census Office lists 25 glassworks in Pittsburgh in 1857. This source agrees that there were nine flint glass works, but lists only seven window glass works and nine green bottle works. The same report lists only 13 glass works in Pittsburgh for 1837.[63]

- ^ J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company had numerous names, which were usually changed when a partner left or joined the company. The company began as Barnes, Hobbs and Company in 1845. In 1849 the name changed to Hobbs, Barnes and Company. In 1856 the name was changed back to Barnes, Hobbs and Company. In 1857 the name was changed to Hobbs and Barnes.[65] The company name was changed again in 1863, becoming J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company.[66] In 1881, after the death of John H. Hobbs, the company name was changed to Hobbs, Brockunier and Company.[67] In 1888 the company was reorganized as Hobbs Glass Company.[68] In 1891 the company became Factory H of the United States Glass Company.[69]

- ^ A different source says the new glass formula "cut the cost of the glass by a third".[73] The soda-lime glass could be pressed, so a combination of the lower materials cost and pressing caused the big reduction in the price of tableware.[74]

- ^ The Census report lists 16 states as producers of glass. The only states producing glass west of the Mississippi River were Missouri and California. Southern states did not produce glass, including: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee.[77]

- ^ Sources have three different hiring dates for Owens: The University of Toledo says Owens was hired in November 1888, Paquette says late summer 1888, and Skrabec says 1889.[89]

- ^ Michael Owens started working at a glass factory at the age of 10 years as a furnace boy.[97]

- ^ The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis lists an estimated "Consumer Price Index" of 29 for 1880, and an estimated "Cost of Living Index" of 25 for 1900. Both are on a 1967=100 basis. The change calculates to a decrease of 13.79 percent.[104]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Shotwell 2002, pp. 32–33

- ^ a b "How Glass is Made – What is glass made of? The wonders of glass all come down to melting sand". Corning. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 94

- ^ Shotwell 2002, pp. 114–115

- ^ Scoville 1944, p. 210

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 343

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 45

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 42

- ^ McKearin & McKearin 1966, pp. 31–33

- ^ "Corning Museum of Glass – Annealing Glass". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 48

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 48; "Corning Museum of Glass – Lehr". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 12

- ^ Zerwick 1990, p. 71

- ^ a b Skrabec 2011, p. 20

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 366

- ^ a b Skrabec 2011, p. 21

- ^ a b Skrabec 2011, p. 18

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, pp. 12–13

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 13

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 69

- ^ a b c Skrabec 2007a, p. 7

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 13; Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 36; Skrabec 2007a, p. 7

- ^ a b Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 11

- ^ Glass & Kohrman 2005, pp. 21–22

- ^ Skrabec 2007a, p. 55

- ^ a b Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 91

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 97

- ^ Skrabec 2007a, p. 33; Skrabec 2007, pp. 97–98

- ^ Skrabec 2011, p. 94; "Miami–Erie Canal". Wright State University Libraries' Special Collections and Archives. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Poor 1868, p. 11

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 3

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 32

- ^ "The National Road". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Poor 1868, p. 14

- ^ "Traveling on the National Road". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ United States Interstate Commerce Commission Bureau of Accounts 1966, p. 50

- ^ a b c Dyer & Gross 2001, p. 23

- ^ Scoville 1944, p. 197

- ^ Dyer & Gross 2001, p. 23; Skrabec 2011, p. 19

- ^ a b c Skrabec 2011, p. 19

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 34

- ^ United States Tariff Commission 1937, p. 29

- ^ Skrabec 2011, pp. 18–20

- ^ Skrabec 2011, pp. 20–21

- ^ a b c Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 144

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 144; Jarves 1854, p. 45; Palmer 1979, p. 5

- ^ Jarves 1854, p. 44

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, pp. 35–36, 144

- ^ a b c Shotwell 2002, p. 444

- ^ Zerwick 1990, p. 79

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 443

- ^ Shotwell 2002, pp. 49, 444

- ^ a b c "Today in History - February 28 - The B & O Railroad". U.S. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on February 19, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Poor 1868, p. 20

- ^ Skrabec 2011, p. 24

- ^ a b United States 1853, p. lxxi

- ^ Poor 1868, pp. 20–21

- ^ "Confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, Pittsburgh, P.A." McConnell Library, Radford University. Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ Skrabec 2007a, p. 7; Skrabec 2011, p. 19

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 4

- ^ Moore 1924, p. 379

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 88

- ^ Madarasz, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania & Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center 1998, p. 144; "Bakewell, Pears & Co. - American, 1844 - 1880". Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Archived from the original on February 17, 2024. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ a b Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 9

- ^ a b c Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 10

- ^ Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 14

- ^ Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 21

- ^ Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 22

- ^ Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, pp. 8–9

- ^ Shotwell 2002, pp. 243–244

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 79; Dyer & Gross 2001, pp. 30–31

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 70

- ^ Skrabec 2007, pp. 70–71

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 2

- ^ a b Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 3

- ^ a b Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 9

- ^ a b c Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 11

- ^ Skrabec 2007a, p. 25

- ^ Skrabec 2007a, pp. 7–8

- ^ "History of the Fostoria Glass Company 1887-1986". Fostoria Glass Society of America Glass Museum. 14 March 2022. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.; Schaffer, Scott (January 4, 2023). "Hartford City and Blackford County: Forged by Glass". News Times (Hartford City). Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Wynn 1908, p. 31

- ^ Wynn 1908, p. 31; Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 10

- ^ Wynn 1908, p. 33

- ^ Wynn 1908, p. 35

- ^ a b Wynn 1908, p. 36

- ^ a b "Timeline: Owens-Illinois and the Glass Industry in Toledo". University of Toledo, Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections. Archived from the original on February 18, 2024. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ Skrabec 2007, pp. 27, 124; "Timeline: Owens-Illinois and the Glass Industry in Toledo". University of Toledo, Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections. Archived from the original on February 18, 2024. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ "Timeline: Owens-Illinois and the Glass Industry in Toledo". University of Toledo, Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections. Archived from the original on February 18, 2024. Retrieved February 18, 2024.; Paquette 2002, pp. 323–324; Skrabec 2007, p. 124

- ^ Skrabec 2007, pp. 13–14

- ^ a b "Owens the Innovator". University of Toledo Library, Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Skrabec 2007, p. 13

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 13; "Owens the Innovator". University of Toledo Library, Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Syrup Off the Roller: The Libbey-Owens-Ford Company". University of Toledo Library. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, p. 476

- ^ Skrabec 2007a, p. 22

- ^ Skrabec 2011, p. 68

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 478–479

- ^ a b Fones-Wolf 2007, p. 31

- ^ Skrabec 2007a, p. 81

- ^ "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ^ "Banking Panics of the Gilded Age - 1863–1913". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2024.; "The Depression of 1893". Economic History Association. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ "The Depression of 1893". Economic History Association. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "Consumer Price Index, 1800- (Historic data including estimates before the modern U.S. consumer price index (CPI))". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ a b Fones-Wolf 2007, p. 11

- ^ a b Fones-Wolf 2007, p. 13

- ^ Fones-Wolf 2007, pp. 11, 13, 24

- ^ Fones-Wolf 2007, p. 24

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 25

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 27

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 28

- ^ a b United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 29

References

[edit]- Bredehoft, Neila M.; Bredehoft, Thomas H. (1997). Hobbs, Brockunier and Co., Glass: Identification and Value Guide. Paducah, KY: Collector Books. ISBN 978-0-89145-780-0. OCLC 37340501.

- Dyer, Davis; Gross, Daniel (2001). The Generations of Corning: The Life and Times of a Global Corporation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19514-095-8. OCLC 45437326.

- Fones-Wolf, Ken (2007). Glass Towns: Industry, Labor and Political Economy in Appalachia, 1890-1930s. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-25203-131-1. OCLC 69792081.

- Glass, James A.; Kohrman, David (2005). The Gas Boom of East Central Indiana. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-73853-963-8. OCLC 61885891.

- Jarves, Deming (1854). Reminiscences of Glass–making. Boston, Massachusetts: Eastburn's Press. OCLC 14284772. Archived from the original on 2024-03-03. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- Madarasz, Anne; Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania; Senator John Heinz Pittsburgh Regional History Center (1998). Glass: Shattering Notions. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0-93634-001-2. OCLC 39921461.

- McKearin, George S.; McKearin, Helen (1966). American Glass. New York City: Crown Publishers. OCLC 1049801744.

- Moore, N. Hudson (1924). Old Glass, European and American. New York City: Frederick A. Stokes Co. OCLC 1738230. Archived from the original on 2024-03-03. Retrieved 2024-02-23.

- Palmer, Arlene (1979). "American Heroes in Glass: The Bakewell Sulphide Portraits". American Art Journal. 11 (1). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, Smithsonian American Art Museum: 4–26. doi:10.2307/1594129. JSTOR 1594129. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- Paquette, Jack K. (2002). Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s. Xlibris Corp. ISBN 1-4010-4790-4. OCLC 50932436.

- Poor, Henry V. (1868). Poor's Manual of Railroads for 1868–69. New York City: H.V. & H.W. Poor. OCLC 5585553. Archived from the original on May 21, 2023. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- Scoville, Warren C. (September 1944). "Growth of the American Glass Industry to 1880". Journal of Political Economy. 52 (3): 193–216. doi:10.1086/256182. JSTOR 1826160. S2CID 154003064. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- Shotwell, David J. (2002). Glass A to Z. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. pp. 638. ISBN 978-0-87349-385-7. OCLC 440702171.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). Michael Owens and the Glass Industry. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-45560-883-6. OCLC 1356375205.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007a). Glass in Northwest Ohio. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-73855-111-1. OCLC 124093123.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2011). Edward Drummond Libbey, American Glassmaker. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-78648-548-2. OCLC 753968484.

- United States (1853). The Seventh Census of the United States, 1850: Embracing a Statistical View of Each of the States and Territories, Arranged by Counties, Towns, Etc. ... Washington, District of Columbia: R. Armstrong. OCLC 1049765701. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (1917). The Glass Industry. Report on the Cost of Production of Glass in the United States. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 5705310.

- United States Interstate Commerce Commission Bureau of Accounts (1966). Seventy–Ninth Annual Report on Transport Statistics in the United States for the Year Ended December 31, 1965. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. OCLC 11600117. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- United States Tariff Commission (1937). "Flat Glass and Related Glass Products". Report Under the General Provisions of Section 332, Title III, Part II, Tariff Act of 1930. 123 (2): 1–277. OCLC 12562332. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- Weeks, Joseph D.; United States Census Office (1884). Report on the Manufacture of Glass. Washington, District of Columbia: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 2123984. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- Wynn, Margaret (March 1908). "Natural Gas in Indiana: An Exploited Resource". Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History. 4 (1): 31–45. JSTOR 27785154. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- Zerwick, Chloe (1990). A Short History of Glass. New York: H.N. Abrams in association with the Corning Museum of Glass. ISBN 978-0-81093-801-4. OCLC 20220721.