1980s in history

1980s in history refers to significant events in the 1980s.

World events

[edit]Major reforms in the Soviet Union

[edit]

| 1980s in history | |

5 kopeck perestroika commemorative postage stamp, 1988 | |

| Russian | перестройка |

|---|---|

| Romanization | perestroyka |

| IPA | [pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə] |

| Literal meaning | rebuilding, restructuring |

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

Perestroika (/ˌpɛrəˈstrɔɪkə/ PERR-ə-STROY-kə; Russian: перестройка, IPA: [pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə] )[1] was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associated with CPSU general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and his glasnost (meaning "transparency") policy reform. The literal meaning of perestroika is "restructuring", referring to the restructuring of the political economy of the Soviet Union, in an attempt to end the Era of Stagnation.

Perestroika allowed more independent actions from various ministries and introduced many market-like reforms. The purported goal of perestroika, however, was not to end the planned economy but rather to make socialism work more efficiently to better meet the needs of Soviet citizens by adopting elements of liberal economics.[2] The process of implementing perestroika added to existing shortages, and created political, social, and economic tensions within the Soviet Union.[3][4] Furthermore, it is often blamed for the political ascent of nationalism and nationalist political parties in the constituent republics.[5]

Gorbachev first used the term in a speech during his visit to Tolyatti in 1986. Perestroika lasted from 1985 until 1991, and is often argued to be a significant cause of the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[6]

With respect to the foreign policy Gorbachev promoted "new political thinking": de-ideologization of international politics, abandoning the concept of class struggle, priority of universal human interests over the interests of any class, increasing interdependence of the world, and mutual security based on political rather than military instruments. The doctrine constituted a significant shift from the previous principles of the Soviet foreign politics.[7][8][9] This marked the end of the Cold War.[10]1989 revolutions

[edit]

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism,[11] were a revolutionary wave of liberal democracy movements that resulted in the collapse of most Marxist–Leninist governments in the Eastern Bloc and other parts of the world. This revolutionary wave is sometimes referred to as the Autumn of Nations,[12][13][14][15][16] a play on the term Spring of Nations that is sometimes used to describe the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe. The Revolutions of 1989 were a key factor in the dissolution of the Soviet Union—one of the two global superpowers—and in the abandonment of communist regimes in many parts of the world, some of which were violently overthrown. These events drastically altered the world's balance of power, marking the end of the Cold War and the beginning of the post-Cold War era.

The earliest recorded protests to be part of the Revolutions of 1989 began in Kazakhstan, then part of the Soviet Union, in 1986, with student demonstrations,[17][18] and the last chapter of the revolutions ended in 1996, when Ukraine abolished the Soviet political system of government, adopting a new constitution which replaced the Soviet-era constitution.[19] The main region of these revolutions was Central Europe, starting in Poland[20][21] with the Polish workers' mass-strike movement in 1988, and the revolutionary trend continued in Hungary, East Germany, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. On 4 June 1989, Poland's Solidarity trade union won an overwhelming victory in partially free elections, leading to the peaceful fall of communism in Poland. Also in June 1989, Hungary began dismantling its section of the physical Iron Curtain. In August 1989, the opening of a border gate between Austria and Hungary set in motion a peaceful chain reaction, in which the Eastern Bloc disintegrated. This led to mass demonstrations in cities of East Germany such as Leipzig and subsequently to the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, which served as the symbolic gateway to German reunification in 1990. One feature common to most of these developments was the extensive use of campaigns of civil resistance, demonstrating popular opposition to the continuation of one-party rule and contributing to pressure for change.[22] Romania was the only country in which citizens and opposition forces used violence to overthrow its communist regime,[23] although Romania was politically isolated from the rest of the Eastern Bloc.

The Soviet Union itself became a multi-party semi-presidential republic from March 1990 and held its first presidential election, marking a drastic change as part of its reform program. The Soviet Union dissolved in December 1991, resulting in seven new countries which had declared their independence from the Soviet Union over the course of the year, while the Baltic states regained their independence in September 1991 along with Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia. The rest of the Soviet Union, which constituted the bulk of the area, continued with the establishment of the Russian Federation. Albania and Yugoslavia abandoned communism between 1990 and 1992, by which time Yugoslavia had split into five new countries. Czechoslovakia dissolved three years after the end of communist rule, splitting peacefully into the Czech Republic and Slovakia on 1 January 1993.[24] North Korea abandoned Marxism–Leninism in 1992.[25] The Cold War is considered to have "officially" ended on 3 December 1989 during the Malta Summit between the Soviet and American leaders.[26] However, many historians argue that the dissolution of the Soviet Union on 26 December 1991 was the end of the Cold War.[27]

The impact of these events were felt in many third world socialist states throughout the world. Concurrently with events in Poland, protests in Tiananmen Square (April–June 1989) failed to stimulate major political changes in Mainland China, but influential images of resistance during that protest helped to precipitate events in other parts of the globe. Three Asian countries, namely Afghanistan, Cambodia[28] and Mongolia, had abandoned communism by 1992–1993, either through reform or conflict. Eight countries in Africa or its environs also abandoned it, namely Ethiopia, Angola, Benin, Congo-Brazzaville, Mozambique, Somalia, as well as South Yemen, which unified with North Yemen to form the Republic of Yemen. Political reforms varied, but in only five countries were Marxist-Leninist communist parties able to retain a monopoly on power; namely China, Cuba, Laos, North Korea, and Vietnam. Vietnam, Laos, and China made economic reforms in the following years to adopt some forms of market economy under market socialism. The European political landscape changed drastically, with several former Eastern Bloc countries joining NATO and the European Union, resulting in stronger economic and social integration with Western Europe and North America. Many communist and socialist organisations in the West turned their guiding principles over to social democracy and democratic socialism. In contrast, and somewhat later, in South America, a pink tide began in Venezuela in 1999 and shaped politics in the other parts of the continent through the early 2000s. Meanwhile, in certain countries the aftermath of these revolutions resulted in conflict and wars, including various post-Soviet conflicts that remain frozen to this day as well as large-scale wars, most notably the Yugoslav Wars which led to the Bosnian genocide in 1995.[29][30]Science and Technology

[edit]Rise of personal computers

[edit]

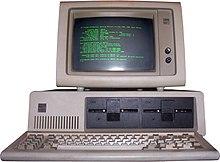

During the early 1980s, home computers were further developed for household use, with software for personal productivity, programming and games. They typically could be used with a television already in the home as the computer display, with low-detail blocky graphics and a limited color range, and text about 40 characters wide by 25 characters tall. Sinclair Research,[31] a UK company, produced the ZX Series—the ZX80 (1980), ZX81 (1981), and the ZX Spectrum; the latter was introduced in 1982, and totaled 8 million unit sold. Following came the Commodore 64, totaled 17 million units sold,[32][33] the Galaksija (1983)[34] introduced in Yugoslavia and the Amstrad CPC series (464–6128).

In the same year, the NEC PC-98 was introduced, which was a very popular personal computer that sold in more than 18 million units.[35] Another famous personal computer, the revolutionary Amiga 1000, was unveiled by Commodore on 23 July 1985. The Amiga 1000 featured a multitasking, windowing operating system, color graphics with a 4096-color palette, stereo sound, Motorola 68000 CPU, 256 KB RAM, and 880 KB 3.5-inch disk drive, for US$1,295.[36]

IBM's first PC was introduced on 12 August 1981 setting what became a mass market standard for PC architecture.[37]

In 1982 The Computer was named Machine of the Year by Time magazine.[38]

Somewhat larger and more expensive systems were aimed at office and small business use. These often featured 80-column text displays but might not have had graphics or sound capabilities. These microprocessor-based systems were still less costly than time-shared mainframes or minicomputers.

Workstations were characterized by high-performance processors and graphics displays, with large-capacity local disk storage, networking capability, and running under a multitasking operating system. Eventually, due to the influence of the IBM PC on the personal computer market, personal computers and home computers lost any technical distinction. Business computers acquired color graphics capability and sound, and home computers and game systems users used the same processors and operating systems as office workers. Mass-market computers had graphics capabilities and memory comparable to dedicated workstations of a few years before. Even local area networking, originally a way to allow business computers to share expensive mass storage and peripherals, became a standard feature of personal computers used at home.

An increasingly important set of uses for personal computers relied on the ability of the computer to communicate with other computer systems, allowing interchange of information. Experimental public access to a shared mainframe computer system was demonstrated as early as 1973 in the Community Memory project, but bulletin board systems and online service providers became more commonly available after 1978. Commercial Internet service providers emerged in the late 1980s, giving public access to the rapidly growing network.

In 1984, Apple Computer launched the Macintosh, with an advertisement during the Super Bowl. The Macintosh was the first successful mass-market mouse-driven computer with a graphical user interface or 'WIMP' (Windows, Icons, Menus, and Pointers). Based on the Motorola 68000 microprocessor, the Macintosh included many of the Lisa's features at a price of US$2,495. The Macintosh was introduced with 128 KB of RAM and later that year a 512 KB RAM model became available. To reduce costs compared the Lisa, the year-younger Macintosh had a simplified motherboard design, no internal hard drive, and a single 3.5-inch floppy drive. Applications that came with the Macintosh included MacPaint, a bit-mapped graphics program, and MacWrite, which demonstrated WYSIWYG word processing.

Tthe Macintosh was a successful personal computer for years to come. This is particularly due to the introduction of desktop publishing in 1985 through Apple's partnership with Adobe. This partnership introduced the LaserWriter printer and Aldus PageMaker to users of the personal computer. During Steve Jobs's hiatus from Apple, a number of different models of Macintosh, including the Macintosh Plus and Macintosh II, were released to a great degree of success. The entire Macintosh line of computers was IBM's major competition up until the early 1990s.Portable audio

[edit]Walkman is a brand of portable audio players manufactured and marketed by Japanese company Sony since 1979. The original Walkman started out as a portable cassette player[39][40] and the brand was later extended to serve most of Sony's portable audio devices; since 2011 it consists exclusively of digital flash memory players. The current flagship product as of 2022 is the WM1ZM2 player.[41]

Walkman cassette players were very popular during the 1980s, which led to "walkman" becoming an genericized label term for personal compact stereos of any producer or brand.[42] 220 million cassette-type Walkmen were sold by the end of production in 2010;[43] including digital Walkman devices such as DAT, MiniDisc, CD (originally Discman then renamed the CD Walkman) and memory-type media players,[44][45] it has sold approximately 400 million at this time.[43] The Walkman brand has also been applied to transistor radios, and Sony Ericsson mobile phones.

Video

[edit]The first consumer videocassette recorders (VCRs) used Sony U-matic technology and were launched in 1971. Philips entered the domestic market the following year with the N1500.[46] Sony's Betamax (1975) and JVC's VHS (1976) created a mass-market for VCRs and the two competing systems battled the videotape format war, which VHS ultimately won. In Europe, Philips had developed the Video 2000 format, which did not find favor with the TV rental companies in the UK and lost out to VHS.

At first VCRs and videocassettes were very expensive, but by the late 1980s the price had come down enough to make them affordable to a mainstream audience. Videocassettes finally made it possible for consumers to buy or rent a complete film and watch it at home whenever they wished, rather than going to a movie theater or having to wait until it was telecast. It gave birth to video rental stores, Blockbuster the largest chain, which lasted from 1985 to 2005. It also made it possible for a VCR owner to begin time shifting their viewing of films and other television programs. This caused an enormous change in viewing practices, as one no longer had to wait for a repeat of a program that had been missed. The shift to home viewing also changed the movie industry's revenue streams, because home renting created an additional window of time in which a film could make money. In some cases, films that did only modestly in their theater releases went on to have strong performances in the rental market (e.g., cult films).

VHS became the leading consumer tape format for home movies after the videotape format war, though its follow-ups S-VHS, W-VHS and D-VHS never caught up in popularity. In the early 2000s in the prerecorded video market, VHS began to be displaced by DVD. The DVD format has several advantages over VHS tape. A DVD is much better able to take repeated viewings than VHS tape. Whereas a VHS tape can be erased though degaussing, DVDs and other optical discs are not affected by magnetic fields. DVDs can still be damaged by scratches. DVDs are smaller and take less space to store. DVDs can support both standard 4x3 and widescreen 16x9 screen aspect ratios and DVDs can provide twice the video resolution of VHS. DVD supports random access while a VHS tape is restricted to sequential access and must be rewound. DVDs can have interactive menus, multiple language tracks, audio commentaries, closed captioning and subtitling (with the option of turning the subtitles on or off, or selecting subtitles in several languages). Moreover, a DVD can be played on a computer.

Due to these advantages, by the mid-2000s, DVDs were the dominant form of prerecorded video movies. Through the late 1990s and early 2000s consumers continued to use VCRs to record over-the-air TV shows, because consumers could not make home recordings onto DVDs. This last barrier to DVD domination was broken in the late 2000s with the advent of inexpensive DVD recorders and digital video recorders (DVRs). In July 2016, the last known manufacturer of VCRs, Funai, announced that it was ceasing VCR production.[47]

A camcorder is a self-contained portable electronic device with video and recording as its primary function. It is typically equipped with an articulating screen mounted on the left side, a belt to facilitate holding on the right side, hot-swappable battery facing towards the user, hot-swappable recording media, and an internally contained quiet optical zoom lens.

The earliest camcorders were tape-based, recording analog signals onto videotape cassettes. In the 2000s, digital recording became the norm, and additionally tape was replaced by storage media such as mini-HDD, MiniDVD, internal flash memory and SD cards.[48]

More recent devices capable of recording video are camera phones and digital cameras primarily intended for still pictures, whereas dedicated camcorders are often equipped with more functions and interfaces than more common cameras, such as an internal optical zoom lens that is able to operate silently with no throttled speed, whereas cameras with protracting zoom lenses commonly throttle operation speed during video recording to minimize acoustic disturbance. Additionally, dedicated units are able to operate solely on external power with no battery inserted.Africa

[edit]Uganda

[edit][[File:none;

|thumb|]]

The Ugandan Bush War was a civil war fought in Uganda by the official Ugandan government and its armed wing, the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA), against a number of rebel groups, most importantly the National Resistance Army (NRA), from 1980 to 1986.

The unpopular President Milton Obote was overthrown in a coup d'état in 1971 by General Idi Amin, who established a military dictatorship. Amin was overthrown in 1979 following the Uganda-Tanzania War, but his loyalists started the Bush War by launching an insurgency in the West Nile region in 1980. Subsequent elections saw Obote return to power in a UNLA-ruled government. Several opposition groups claimed the elections were rigged, and united as the NRA under the leadership of Yoweri Museveni to start an armed uprising against Obote's government on 6 February 1981. Obote was overthrown and replaced as president by his general Tito Okello in 1985 during the closing months of the conflict. Okello formed a coalition government consisting of his followers and several armed opposition groups, which agreed to a peace deal. In contrast, the NRA refused to compromise with the government, and conquered much of western and southern Uganda in a number of offensives from August to December 1985.

The NRA captured Kampala, Uganda's capital, in January 1986. It subsequently established a new government with Museveni as president, while the UNLA fully disintegrated in March 1986. Obote and Okello went into exile. Despite the nominal end of the civil war, numerous anti-NRA rebel factions and militias remained active, and would continue to fight Museveni's government in the next decades.Asia

[edit]Iran-Iraq War

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Political offices

Rise to power Presidency Desposition Elections and referendums  |

||

The Iran–Iraq War, also known as the First Gulf War,[a] was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. Active hostilities began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for nearly eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Council Resolution 598 by both sides. Iraq's primary rationale for the attack against Iran cited the need to prevent Ruhollah Khomeini—who had spearheaded the Iranian revolution in 1979—from exporting the new Iranian ideology to Iraq. There were also fears among the Iraqi leadership of Saddam Hussein that Iran, a theocratic state with a population predominantly composed of Shia Muslims, would exploit sectarian tensions in Iraq by rallying Iraq's Shia majority against the Baʽathist government, which was officially secular and dominated by Sunni Muslims. Iraq also wished to replace Iran as the power player in the Persian Gulf, which was not seen as an achievable objective prior to the Islamic Revolution because of Pahlavi Iran's economic and military superiority as well as its close relationships with the United States and Israel.

The Iran–Iraq War followed a long-running history of territorial border disputes between the two states, as a result of which Iraq planned to retake the eastern bank of the Shatt al-Arab that it had ceded to Iran in the 1975 Algiers Agreement. Iraqi support for Arab separatists in Iran increased following the outbreak of hostilities; Saddam disputedly may have wished to annex Iran's Arab-majority Khuzestan province.

While the Iraqi leadership had hoped to take advantage of Iran's post-revolutionary chaos and expected a decisive victory in the face of a severely weakened Iran, the Iraqi military only made progress for three months, and by December 1980, the Iraqi invasion had stalled. The Iranian military began to gain momentum against the Iraqis and regained all lost territory by June 1982. After pushing Iraqi forces back to the pre-war border lines, Iran rejected United Nations Security Council Resolution 514 and launched an invasion of Iraq. The subsequent Iranian offensive within Iraqi territory lasted for five years, with Iraq taking back the initiative in mid-1988 and subsequently launching a series of major counter-offensives that ultimately led to the conclusion of the war in a stalemate.

The eight years of war-exhaustion, economic devastation, decreased morale, military stalemate, inaction by the international community towards the use of weapons of mass destruction by Iraqi forces on Iranian soldiers and civilians, as well as increasing Iran–United States military tensions all culminated in Iran's acceptance of a ceasefire brokered by the United Nations Security Council. In total, around 500,000 people were killed during the Iran–Iraq War, with Iran bearing the larger share of the casualties, excluding the tens of thousands of civilians killed in the concurrent Anfal campaign that targeted Iraqi Kurdistan. The end of the conflict resulted in neither reparations nor border changes, and the combined financial losses suffered by both combatants is believed to have exceeded US$1 trillion.[49] There were a number of proxy forces operating for both countries: Iraq and the pro-Iraqi Arab separatist militias in Iran were most notably supported by the National Council of Resistance of Iran; whereas Iran re-established an alliance with the Iraqi Kurds, being primarily supported by the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. During the conflict, Iraq received an abundance of financial, political, and logistical aid from the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, France, Italy, Yugoslavia, and the overwhelming majority of Arab countries. While Iran was comparatively isolated to a large degree, it received a significant amount of aid from Syria, Libya, China, North Korea, Israel, Pakistan, and South Yemen.

The conflict has been compared to World War I in terms of the tactics used by both sides, including large-scale trench warfare with barbed wire stretched across fortified defensive lines, manned machine-gun posts, bayonet charges, Iranian human wave attacks, Iraq's extensive use of chemical weapons, and deliberate attacks on civilian targets. The discourses on martyrdom formulated in the Iranian Shia Islamic context led to the widespread usage of human wave attacks and thus had a lasting impact on the dynamics of the conflict.[50]China

[edit]

Deng Xiaoping (Chinese: 邓小平;[b] 22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's Republic of China from 1978 to 1989. In the aftermath of Mao Zedong's death in 1976, Deng succeeded in consolidating power to lead China through a period of Reform and Opening Up that transformed its economy into a socialist market economy. He is widely regarded as the "Architect of Modern China" for his contributions to socialism with Chinese characteristics and Deng Xiaoping Theory.[55][56][57][page needed]

Born in Sichuan, Deng first became interested in Marxism–Leninism while studying abroad in France in the 1920s. In 1924, he joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and continued his studies in Moscow. Following the outbreak of the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang (KMT) and CCP, Deng worked in the Jiangxi Soviet, where he developed good relations with Mao. He served as a political commissar in the Chinese Red Army during the Long March and Second Sino-Japanese War, and later helped to lead the People's Liberation Army (PLA) to victory in the civil war, participating in the PLA's capture of Nanjing. After the proclamation of the PRC in 1949, Deng held several key regional roles, eventually rising to vice premier and CCP secretary-general in the 1950s. He presided over economic reconstruction efforts and played a significant role in the Anti-Rightist Campaign. During the Cultural Revolution from 1966, Deng was condemned as the party's "number two capitalist roader" after Liu Shaoqi, and was purged twice by Mao. After Mao's death in 1976, Deng outmaneuvered his rivals to become the country's leader in 1978.

Upon coming to power, Deng began a massive overhaul of China's infrastructure and political system. Due to the institutional disorder and political turmoil from the Mao era, he and his allies launched the Boluan Fanzheng program which sought to restore order by rehabilitating those who were persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. He also initiated a reform and opening up program that introduced elements of market capitalism to the Chinese economy by designating special economic zones within the country. In 1980, Deng embarked on a series of political reforms including the setting of constitutional term limits for state officials and other systematic revisions which were incorporated in the country's fourth constitution. He later championed a one-child policy to deal with China's perceived overpopulation crisis, helped establish China's nine-year compulsory education, and oversaw the launch of the 863 Program to promote science and technology. The reforms carried out by Deng and his allies gradually led China away from a command economy and Maoist dogma, opened it up to foreign investments and technology, and introduced its vast labor force to the global market—thereby transforming China into one of the world's fastest-growing economies.[58] Deng helped negotiate the eventual return of Hong Kong and Macau to China (which took place after his death) and developed the principle of "one country, two systems" for their governance.

During the course of his leadership, Deng was named the Time Person of the Year for 1978 and 1985.[59][60] Despite his contributions to China's modernization, Deng's legacy is also marked by controversy. He ordered the military crackdown on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, which ended his political reforms and remains a subject of global criticism.[61] The one-child policy introduced in Deng's era also drew criticism. Nonetheless, his policies laid the foundation for China's emergence as a major global power.[62] Deng was succeeded as paramount leader by Jiang Zemin, who continued his policies.Iran

[edit]

Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini[c] (17 May 1900 or 24 September 1902[d] – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian Islamic revolutionary, politician and religious leader who served as the first Supreme Leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the main leader of the Iranian Revolution, which overthrew Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and ended the Iranian monarchy. Ideologically a Shia Islamist, Khomeini's religious and political ideas are known as Khomeinism.

Born in Khomeyn, in what is now Iran's Markazi province, his father was murdered in 1903 when Khomeini was just two years old. He began studying the Quran and Arabic from a young age and was assisted in his religious studies by his relatives, including his mother's cousin and older brother. Khomeini was a high ranking cleric in Twelver Shi'ism, an ayatollah, a marja' ("source of emulation"), a mujtahid or faqīh (an expert in sharia), and author of more than 40 books. His opposition to the White Revolution resulted in his state-sponsored expulsion to Bursa in 1964. Nearly a year later, he moved to Najaf, where speeches he gave outlining his religiopolitical theory of Guardianship of the Jurist were compiled into Islamic Government.

Khomeini was Time magazine's Man of the Year in 1979 for his international influence and has been described as the "virtual face of Shia Islam in Western popular culture", where he was known for his support of the hostage takers during the Iran hostage crisis, his fatwa calling for the murder of British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie who insulted prophet Muhammad,[63] and for referring to the United States as the "Great Satan" and the Soviet Union as the "Lesser Satan". Following the revolution, Khomeini became the country's first supreme leader, a position created in the constitution of the Islamic Republic as the highest-ranking political and religious authority of the nation, which he held until his death. Most of his period in power was taken up by the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–1988. He was succeeded by Ali Khamenei on 4 June 1989.

The subject of a pervasive cult of personality, Khomeini is officially known as Imam Khomeini inside Iran and by his supporters internationally. His funeral was attended by up to 10 million people, or one fifth of Iran's population, one of the largest funerals and human gatherings in history.[64][65] In Iran, his gold-domed tomb in Tehran's Behesht-e Zahrāʾ cemetery has become a shrine for his adherents, and he is legally considered "inviolable", and it is illegal to insult him.[66] His supporters view him as a champion of Islamic revival, anti-racism, independence, reducing foreign influence in Iran, and anti-imperialism.[67] Critics accuse him of anti-Western and anti-Semitic rhetoric, anti-democratic actions and human rights violations.[68][69][70]Iraq

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Political offices

Rise to power Presidency Desposition Elections and referendums  |

||

Saddam Hussein[f] (28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician and revolutionary who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 1979 until his overthrow in 2003. He also served as prime minister of Iraq from 1979 to 1991 and later from 1994 to 2003. He was a leading member of the revolutionary Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party and later its Iraqi regional branch. Ideologically, he espoused Ba'athism, a mix of Arab nationalism and Arab socialism, while the policies and political ideas he championed are collectively known as Saddamism.

Saddam was born in the village of Al-Awja, near Tikrit in northern Iraq, to a Sunni Arab family.[75] He joined the Ba'ath Party in 1957, and later in 1966 the Iraqi and Baghdad-based Ba'ath parties. He played a key role in the 17 July Revolution and was appointed vice president of Iraq by Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr. During his time as vice president, Saddam nationalized the Iraq Petroleum Company, diversifying the Iraqi economy. He presided over the Second Iraqi–Kurdish War (1974–1975) and the Algiers Agreement which settled territorial disputes along the Iran–Iraq border. Following al-Bakr's resignation in 1979, Saddam formally took power, although he had already been the de facto head of Iraq for several years. Positions of power in the country were mostly filled with Sunni Arabs, a minority that made up about a fifth of the population.[76]

In 1979, upon taking office, Saddam purged the Ba'ath Party. He ordered the invasion of Iran in 1980 in a purported effort to capture Iran's Arab-majority Khuzestan province, thwart Iranian attempts to export its 1979 revolution to the Arab world, and end Iranian calls for the overthrow of the Sunni-dominated Ba'athist regime. The Iran–Iraq War ended in stalemate after nearly eight years in a ceasefire, after a million people were killed and Iran suffered economic losses of $561 billion. At the end of the war, Saddam ordered the Anfal campaign against Kurdish rebels who sided with Iran, recognized by Human Rights Watch as an act of genocide. Later, Saddam accused his ally Kuwait of slant-drilling the Iraqi oil reserves and invaded the country, initiating the Gulf War (1990–1991), which ended in Iraq's defeat by a multinational coalition led by the United States. The United Nations subsequently placed sanctions against Iraq. Saddam brutally suppressed the 1991 Iraqi uprisings of the Kurds and Shias, which sought to gain independence or overthrow the government. Saddam adopted an anti-American stance and established the Faith Campaign, pursuing an Islamist agenda in Iraq.

In 2003, the United States and its coalition of allies invaded Iraq, accusing Saddam of developing weapons of mass destruction and of having ties with al-Qaeda, accusations that turned out to be false. After the quick coalition victory in the war, the Ba'ath Party was banned and Saddam went into hiding. After his capture on 13 December 2003, his trial took place under the Iraqi Interim Government. On 5 November 2006, Saddam was convicted by the Iraqi High Tribunal of crimes against humanity related to the 1982 Dujail massacre and sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed on 30 December 2006.

A highly polarizing and controversial figure, Saddam dominated Iraqi politics for 35 years and was the subject of a cult of personality. Many Arabs regard Saddam as a resolute leader who challenged Western imperialism, opposed the Israeli occupation of Palestine, and resisted foreign intervention in the region. Conversely, many Iraqis, particularly Shias and Kurds, perceive him negatively as a dictator responsible for severe authoritarianism, repression, and numerous injustices. Human Rights Watch estimated that Saddam's regime was responsible for the murder or disappearance of 250,000 to 290,000 Iraqis. Saddam's government has been described by several analysts as authoritarian and totalitarian, and by some as fascist, although the applicability of those labels has been contested.Europe

[edit]France

[edit]

François Maurice Adrien Marie Mitterrand[g] (26 October 1916 – 8 January 1996) was a French politician and statesman who served as President of France from 1981 to 1995, the longest holder of that position in the history of France. As a former Socialist Party First Secretary, he was the first left-wing politician to assume the presidency under the Fifth Republic.

Due to family influences, Mitterrand started his political life on the Catholic nationalist right. He served under the Vichy regime during its earlier years. Subsequently he joined the Resistance, moved to the left, and held ministerial office several times under the Fourth Republic. Mitterrand opposed Charles de Gaulle's establishment of the Fifth Republic. Although at times a politically isolated figure, he outmanoeuvered rivals to become the left's standard bearer in the 1965 and 1974 presidential elections, before being elected president in the 1981 presidential election. He was re-elected in 1988 and remained in office until 1995.

Mitterrand invited the Communist Party into his first government, which was a controversial decision at the time. However, the Communists were boxed in as junior partners and, rather than taking advantage, saw their support eroded, eventually leaving the cabinet in 1984.

Early in his first term, Mitterand followed a radical left-wing economic agenda, including nationalisation of key firms and the introduction of the 39-hour work week. He likewise pushed a socially liberal agenda with reforms such as the abolition of the death penalty, and the end of a government monopoly in radio and television broadcasting. He was also a strong promoter of French culture and implemented a range of costly "Grands Projets". However, faced with economic tensions, he soon abandoned his nationalization programme, in favour of austerity and market liberalization policies. In 1985, he was faced with a major controversy after ordering the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior, a Greenpeace vessel docked in Auckland. Later in 1991, he became the first French President to appoint a female prime minister, Édith Cresson. During his presidency, Mitterrand was twice forced by the loss of a parliamentary majority into "cohabitation governments" with conservative cabinets led, respectively, by Jacques Chirac (1986–1988), and Édouard Balladur (1993–1995).

Mitterrand’s foreign and defence policies built on those of his Gaullist predecessors, except in regards to their reluctance to support European integration, which he reversed. His partnership with German chancellor Helmut Kohl advanced European integration via the Maastricht Treaty, and he accepted German reunification.

Less than eight months after leaving office, he died from the prostate cancer he had successfully concealed for most of his presidency. Beyond making the French Left electable, Mitterrand presided over the rise of the Socialist Party to dominance of the left, and the decline of the once-dominant Communist Party.[h]Germany

[edit]

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (German: [ˈhɛlmuːt ˈkoːl] ; 3 April 1930 – 16 June 2017) was a German politician who served as chancellor of Germany from 1990 to 1998 and, prior to German reunification, as the chancellor of West Germany from 1982 to 1990. He was leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998 and oversaw the end of the Cold War, the German reunification and the creation of the European Union (EU). Kohl’s 16-year tenure is the longest of any German chancellor since Otto von Bismarck, and is the longest for any democratically elected chancellor of Germany.

Born in Ludwigshafen to a Catholic family, Kohl joined the CDU in 1946 at the age of 16. He earned a PhD in history at Heidelberg University in 1958, and worked as a business executive before becoming a full-time politician. He was elected as the youngest member of the Parliament of Rhineland-Palatinate in 1959 and from 1969 to 1976 was minister president of the Rhineland-Palatinate state. Viewed during the 1960s and the early 1970s as a progressive within the CDU, he was elected national chairman of the party in 1973. After he had become party leader, Kohl was increasingly seen as a more conservative figure. In the 1976 and 1980 federal elections his party performed well, but the social-liberal government of social democrat Helmut Schmidt was able to remain in power. After Schmidt had lost the support of the liberal FDP in 1982, Kohl was elected Chancellor through a constructive vote of no confidence, forming a coalition government with the FDP. Kohl chaired the G7 in 1985 and 1992.

As Chancellor, Kohl was committed to European integration and especially to the Franco-German relationship; he was also a steadfast ally of the United States and supported Ronald Reagan's more aggressive policies to weaken the Soviet Union. Following the Revolutions of 1989, his government acted decisively, culminating in the German reunification in 1990. Kohl and French president François Mitterrand were the architects of the Maastricht Treaty which established the EU and the Euro currency.[80] Kohl was also a central figure in the eastern enlargement of the EU, and his government led the effort to push for international recognition of Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina when the states declared independence. He played an instrumental role in resolving the Bosnian War. Domestically Kohl's policies from 1990 focused on integrating former East Germany into reunified Germany, and he moved the federal capital from the "provisional capital" Bonn back to Berlin, although he never resided there because the government offices were only relocated in 1999. Kohl also greatly increased federal spending on arts and culture. After his chancellorship, Kohl became honorary chairman of the CDU in 1998 but resigned from the position in 2000 in the wake of the CDU donations scandal which damaged his reputation domestically.

Kohl received the 1988 Charlemagne Prize and was named Honorary Citizen of Europe by the European Council in 1998. Following his death, Kohl was honoured with the first-ever European act of state in Strasbourg.[81] Kohl was described as "the greatest European leader of the second half of the 20th century" by US presidents George H. W. Bush[82] and Bill Clinton.[83]Russia

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Former General Secretary of the CPSU Secretariate (1985–1991)

Presidency (1990–1991)

Foreign policy Post-leadership

Media gallery |

||

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev[i] (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1985 and additionally as head of state beginning in 1988, as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 1988 to 1989, Chairman of the Supreme Soviet from 1989 to 1990 and the president of the Soviet Union from 1990 to 1991. Ideologically, Gorbachev initially adhered to Marxism–Leninism but moved towards social democracy by the early 1990s. He was the only Soviet leader born after the country's foundation.

Gorbachev was born in Privolnoye, Russian SFSR, to a poor peasant family of Russian and Ukrainian heritage. Growing up under the rule of Joseph Stalin in his youth, he operated combine harvesters on a collective farm before joining the Communist Party, which then governed the Soviet Union as a one-party state. Studying at Moscow State University, he married fellow student Raisa Titarenko in 1953 and received his law degree in 1955. Moving to Stavropol, he worked for the Komsomol youth organization and, after Stalin's death, became a keen proponent of the de-Stalinization reforms of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. He was appointed the First Party Secretary of the Stavropol Regional Committee in 1970, overseeing the construction of the Great Stavropol Canal. In 1978, he returned to Moscow to become a Secretary of the party's Central Committee; he joined the governing Politburo (25th term) as a non-voting member in 1979 and a voting member in 1980. Three years after the death of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev—following the brief tenures of Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko—in 1985, the Politburo elected Gorbachev as general secretary, the de facto leader.

Although committed to preserving the Soviet state and its Marxist–Leninist ideals, Gorbachev believed significant reform was necessary for its survival. He withdrew troops from the Soviet–Afghan War and embarked on summits with United States president Ronald Reagan to limit nuclear weapons and end the Cold War. Domestically, his policy of glasnost ("openness") allowed for enhanced freedom of speech and press, while his perestroika ("restructuring") sought to decentralize economic decision-making to improve its efficiency. Ultimately, Gorbachev's democratization measures and formation of the elected Congress of People's Deputies undermined the one-party state. When various Warsaw Pact countries abandoned Marxist–Leninist governance in 1989, he declined to intervene militarily. Growing nationalist sentiment within constituent republics threatened to break up the Soviet Union, leading the hardliners within the Communist Party to launch an unsuccessful coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. In the coup's wake, the Soviet Union dissolved against Gorbachev's wishes. After resigning from the presidency, he launched the Gorbachev Foundation, became a vocal critic of Russian presidents Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin, and campaigned for Russia's social-democratic movement.

Gorbachev is considered one of the most significant figures of the second half of the 20th century. The recipient of a wide range of awards, including the Nobel Peace Prize, in the West he is praised for his role in ending the Cold War, introducing new political and economic freedoms in the Soviet Union, and tolerating both the fall of Marxist–Leninist administrations in eastern and central Europe and the German reunification. Gorbachev has a complicated legacy in Russia. While in power, he had net positive approval ratings, being viewed as a reformer and changemaker. However, as the Soviet Union collapsed as a result of these reforms, so did his approval rating; contemporary Russians often deride him for weakening Russia's global influence and precipitating an economic collapse in the country. Mikhail Gorbachev also ran unsuccessfully in 1996 which, despite neoliberal reforms in Russia at the time, showed mass unpopularity with the results of his administration and possibly regret in the collapse of the USSR.

United Kingdom

[edit]

Margaret Thatcher's tenure as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom began on 4 May 1979 when she accepted an invitation from Queen Elizabeth II to form a government, succeeding James Callaghan of the Labour Party, and ended on 28 November 1990 upon her resignation. She was elected to the position in 1979, having led the Conservative Party since 1975, and won landslide re-elections for the Conservatives in 1983 and 1987. She gained intense media attention as Britain's first female prime minister, and was the longest-serving British prime minister of the 20th century.[87] Her premiership ended when she withdrew from the 1990 Conservative leadership election. As prime minister, Thatcher also served simultaneously as First Lord of the Treasury, Minister for the Civil Service, and Leader of the Conservative Party.

In domestic policy, Thatcher implemented sweeping reforms concerning the affairs of the economy, eventually including the privatisation of most nationalised industries,[88] and the weakening of trade unions.[89] She emphasised reducing the government's role and letting the marketplace decide in terms of the neoliberal ideas pioneered by Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, promoted by her mentor Keith Joseph, and promulgated by the media as Thatcherism.[90] In foreign policy, Thatcher decisively defeated Argentina in the Falklands War in 1982. In longer-range terms, she worked with Ronald Reagan to actively oppose Soviet communism during the Cold War; however, she also promoted collaboration with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in ending the Cold War.[91]

In her first years, Thatcher had a deeply divided cabinet. As the leader of the "dry" faction, she purged most of the One Nation "wet" Conservatives and took full control.[92]: 34 By the late 1980s, however, she had alienated several senior members of her Cabinet with her opposition to greater economic integration into the European Economic Community, which she argued would lead to a federalist Europe and surrender Britain's ability to self govern. She also alienated many Conservative voters and parliamentarians with the imposition of a local poll tax. As her support ebbed away, she was challenged for her leadership and persuaded by Cabinet to withdraw from the second round of voting – ending her eleven-year premiership. She was succeeded by John Major, her Chancellor of the Exchequer.North America

[edit]United States

[edit]

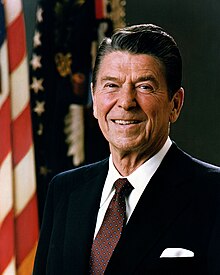

The Reagan era or the Age of Reagan is a periodization of recent American history used by historians and political observers to emphasize that the conservative "Reagan Revolution" led by President Ronald Reagan in domestic and foreign policy had a lasting impact. It overlaps with what political scientists call the Sixth Party System. Definitions of the Reagan era universally include the 1980s, while more extensive definitions may also include the late 1970s, the 1990s, and even the 2000s. In his 2008 book, The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008, historian and journalist Sean Wilentz argues that Reagan dominated this stretch of American history in the same way that Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal legacy dominated the four decades that preceded it.

The Reagan era included ideas and personalities beyond Reagan himself. He is usually characterized as the leader of a broadly-based conservative movement whose ideas dominated national policy-making in areas such as taxes, welfare, defense, the federal judiciary, and the Cold War. Other major conservative figures and organizations of the Reagan era include Jerry Falwell, Phyllis Schlafly, Newt Gingrich, and The Heritage Foundation. The Rehnquist Court, which was inaugurated during Reagan's presidency, handed down several conservative decisions. The Reagan era coincides with the presidency of Reagan, and, in more extensive definitions, the presidencies of Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden. Liberals generally lament the Reagan era, while conservatives generally praise it and call for its continuation in the 21st century. Liberals were significantly influenced as well, leading to the Third Way.

Upon taking office, the Reagan administration implemented an economic policy based on the theory of supply-side economics. Taxes were reduced through the passage of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, while the administration also cut domestic spending and increased military spending. Increasing deficits motivated the passage of tax increases during the George H. W. Bush and Clinton administrations, but taxes were cut again with the passage of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001. During Clinton's presidency, Republicans won passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, a bill which placed several new limits on those receiving federal assistance.

Campaigning for the Democratic nomination in 2008, Barack Obama interpreted how Reagan changed the nation's trajectory:

I think Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America in a way that Richard Nixon did not and in a way that Bill Clinton did not. He put us on a fundamentally different path because the country was ready for it. I think they felt like with all the excesses of the 1960s and 1970s and government had grown and grown but there wasn't much sense of accountability in terms of how it was operating. I think that people . . . he just tapped into what people were already feeling, which was we want clarity, we want optimism, we want a return to that sense of dynamism and entrepreneurship that had been missing.[93]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Entertainment and personal 33rd Governor of California 40th President of the United States Tenure Appointments

|

||

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following his landslide victory over Democrat incumbent president Jimmy Carter and independent congressman John B. Anderson in the 1980 presidential election. Four years later in the 1984 presidential election, he defeated former Democratic vice president Walter Mondale to win re-election in a larger landslide. Reagan served two terms and was succeeded by his vice president, George H. W. Bush, who won the 1988 presidential election. Reagan's 1980 landslide election resulted from a dramatic conservative shift to the right in American politics, including a loss of confidence in liberal, New Deal, and Great Society programs and priorities that had dominated the national agenda since the 1930s.

Domestically, the Reagan administration enacted a major tax cut, sought to cut non-military spending, and eliminated federal regulations. The administration's economic policies, known as "Reaganomics", were inspired by supply-side economics. The combination of tax cuts and an increase in defense spending led to budget deficits, and the federal debt increased significantly during Reagan's tenure. Reagan signed the Tax Reform Act of 1986, simplifying the tax code by reducing rates and removing several tax breaks, and the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, which enacted sweeping changes to U.S. immigration law and granted amnesty to three million illegal immigrants. Reagan also appointed more federal judges than any other president, including four Supreme Court Justices.

Reagan's foreign policy stance was resolutely anti-communist. Its plan of action, known as the Reagan Doctrine, sought to roll back the global influence of the Soviet Union in an attempt to end the Cold War. Under his doctrine, the Reagan administration initiated a massive buildup of the United States military; promoted new technologies such as missile defense systems; and in 1983 undertook an invasion of Grenada, the first major overseas action by U.S. troops since the end of the Vietnam War. The administration also created controversy by granting aid to paramilitary forces seeking to overthrow leftist governments, particularly in war-torn Central America and Afghanistan. Specifically, the Reagan administration engaged in covert arms sales to Iran to fund Contra rebels in Nicaragua that were fighting to overthrow their nation's socialist government. The resulting Iran–Contra affair led to the conviction or resignation of several administration officials. During Reagan's second term, he sought closer relations with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, and the two leaders signed a major arms control agreement known as the INF Treaty.

Historians and political scientists generally rank Reagan in the upper tier of American presidents, and consider him to be one of the most important presidents since Franklin D. Roosevelt. Supporters of Reagan's presidency have pointed to his contributions to the economic recovery of the 1980s, the peaceful end of the Cold War, and a broader restoration of American confidence. Reagan's presidency has also received criticism for rising budget deficits and wealth inequality during and after his presidency. Due to Reagan's popularity with the public and advocacy of American conservatism, some historians have described the period during and after his presidency as the Reagan Era.South America

[edit]Brazil

[edit]

João Baptista de Oliveira Figueiredo (Portuguese: [ʒuˈɐ̃w baˈtʃistɐ dʒi oliˈvejɾɐ fiɡejˈɾedu, ˈʒwɐ̃w -]; 15 January 1918 – 24 December 1999) was a Brazilian military leader and politician who served as the 30th president of Brazil from 1979 to 1985, the last of the military regime that ruled the country following the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état. He was chief of the Secret Service (SNI) during the term of his predecessor, Ernesto Geisel, who appointed him to the presidency at the end of his own term.

He continued the process of redemocratization that Geisel had started and sanctioned a law decreeing amnesty for all political crimes committed during the regime. His term was marked by a severe economic crisis and growing dissatisfaction with the military rule, culminating in the Diretas Já protests of 1984, which clamored for direct elections for the Presidency, the last of which had taken place 24 years prior. Figueiredo opposed this and in 1984 Congress rejected the immediate return of direct elections, in favor of an indirect election by Congress, which was nonetheless won by the opposition candidate Tancredo Neves. Figueiredo retired after the end of his term and died in 1999.Brazil suffered from high inflation and international crises. To try to "unburden the country", the government created several economic plans.[94]

Under the Cruzado Plan, the cruzeiro, the currency in effect at the time, was changed to the cruzado. Salaries were frozen, being readjusted whenever inflation reached 20% (salary trigger). Monetary correction was abolished, and unemployment insurance was created. At first, the plan managed to achieve its goals, reducing unemployment and reducing inflation. The popularity of the plan made the president's party, the PMDB, victorious in the 1985 municipal elections. The party managed to elect 19 of the 25 mayors of the state capitals. The following year, in 1986, the party managed to elect the governors of all states except Sergipe; and in Congress, the party won 261 seats (54%) out of a total of 487 in the Chamber of Deputies, and 45 (62.5%) of the 72 seats in the Federal Senate. However, soon after, the Cruzado Plan began to decay, and the merchants hid their goods in order to use an agio - an additional tax on the product - to be able to sell the products above the established price.[95] After the 1986 elections, the II Cruzado Plan was announced, which caused an excessive increase in prices. The plan failed, and inflation was already over 20%. Finance Minister Dílson Funaro, responsible for the "Cruzado Plans" was replaced by Luís Carlos Bresser-Pereira.[96]

Shortly after Bresser-Pereira took office, inflation reached 23.21%. In order to control the public deficit, through which the government spent more than it collected, an emergency economic plan, the Bresser Plan, was presented in June 1987, instituting a three-month freeze on prices and wages. In order to reduce the public deficit some measures were taken, such as: deactivating the wage trigger, increasing taxes, eliminating the wheat subsidy, and postponing the large projects that were already planned, among them the bullet train between São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, the North-South Railroad, and the petrochemical complex in Rio de Janeiro. Negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were resumed, and the moratorium was suspended. Even with all these measures, inflation reached the alarming rate of 366% in the 12-month period of 1987. Minister Bresser-Pereira resigned from the Ministry of Finance on January 6, 1988, and was replaced by Maílson da Nóbrega.[97]

Minister Maílson da Nóbrega created the Verão Plan in January 1989, which decreed a new price freeze and created a new currency: the Cruzado Novo. Like all the others, this one also failed, and Sarney ended his government in a time of economic recession.Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Arabic: حرب الخليج الأولى, romanized: Ḥarb al-Khalīj al-ʾAwlā; Persian: جنگ ایران و عراق, romanized: Jang-e Irān va Erāq

- ^ /ˈdʌŋ ʃaʊˈpɪŋ/, also UK: /ˈdɛŋ -, - ˈsjaʊpɪŋ/;[51][52][53] Chinese: 邓小平; pinyin: Dèng Xiǎopíng also romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing;[54] born Xiansheng (先圣). In this Chinese name, the family name is Deng.

- ^

- UK: /xɒˈmeɪni/ khom-AY-nee, US: /xoʊ-/ khohm-

- Persian: روحالله خمینی, romanized: Ruhollâh Xomeyni, pronounced [ɾuːholˈlɒːhe xomejˈniː]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

dobwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Saddam (Arabic: صدام), pronounced [sˤɑdˈdæːm] in Modern Standard Arabic, is his personal name, and means "the stubborn one" or "he who confronts". Hussein (sometimes also transliterated as Hussayn or Hussain) is not a surname in the Western sense but a patronymic or nasab, his father's given personal name;[72] Abd al-Majid his grandfather's; al-Tikriti is a laqab meaning he was born and raised in, or near, Tikrit. He was commonly referred to as Saddam Hussein, or Saddam for short. The observation that referring to the deposed Iraqi president as only Saddam is derogatory or inappropriate may be based on the assumption that Hussein is a family name, and "Hussein" was treated this way in English.[72] Thus The New York Times refers to him as "Mr. Hussein",[73] while Encyclopædia Britannica uses just Saddam.[74] A full discussion can be found in the CBC reference preceding this note.

- ^ /səˈdɑːm huːˈseɪn/ sə-DAHM hoo-SAYN; Arabic: صدام حسين, Mesopotamian Arabic: [sˤɐdˈdɑːm ɜħˈsɪe̯n]; also known by his full name Ṣaddām Ḥusayn ʿAbd al-Maǧīd al-Tikrītiyy; Arabic: صدام حسين عبد المجيد التكريتي. He is known mononymously as Saddam.[71][e]

- ^ /ˈmiːtərɒ̃/ or /ˈmɪt-/ ,[77] US also /ˌmiːtɛˈrɒ̃, -ˈrɑːn(d)/;[78][79] French: [fʁɑ̃swa mɔʁis adʁijɛ̃ maʁi mit(ɛ)ʁɑ̃, - moʁ-] .

- ^ As a share of the popular vote in the first presidential round, the Communists shrank from a peak of 21.27% in 1969 to 8.66% in 1995, at the end of Mitterrand's second term.

- ^ UK: /ˈɡɔːrbətʃɒf, ˌɡɔːrbəˈtʃɒf/, US: /-tʃɔːf, -tʃɛf/;[84][85][86] Russian: Михаил Сергеевич Горбачёв, romanized: Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachyov, IPA: [mʲɪxɐˈil sʲɪrˈɡʲejɪvʲɪdʑ ɡərbɐˈtɕɵf]

References

[edit]- ^ Professor Gerhard Rempel, Department of History, Western New England College (2 February 1996). "Gorbachev and Perestroika". Mars.wnec.edu. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mikhail Gorbachev, Perestroika (New York: Harper Collins, 1987), quoted in Mark Kishlansky, ed., Sources of the West: Readings in Western Civilization, 4th ed., vol. 2 (New York: Longman, 2001), p. 322.

- ^ "How 'Glasnost' and 'Perestroika' Changed the World". TIME. 2022-08-30. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Kolesnikov, Andrei (August 8, 2022). "Gorbachev's Revolution". Carnegie Politika. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ "Perestroika: Glasnost, Definition & Soviet Union". HISTORY. 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2024-02-02.

- ^ Kotkin, Stephen (2001). Armageddon Averted. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280245-3.

- ^ "Gorbachev's New Thinking", by David Holloway, Foreign Affairs, vol.68 no.1

- ^ "Gorbachev and New Thinking in Soviet Foreign Policy, 1987-88", USDOS archive

- ^ New Thinking: Foreign Policy under Gorbachev, in: Glenn E. Curtis, ed. Russia: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1996.

- ^ Katrina vanden Heuvel & Stephen F. Cohen. (16 November 2009). "Gorbachev on 1989". Thenation.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012.

- ^ Gehler, Michael; Kosicki, Piotr H.; Wohnout, Helmut (2019). Christian Democracy and the Fall of Communism. Leuven University Press. ISBN 978-9-4627-0216-5.

- ^ Nedelmann, Birgitta; Sztompka, Piotr (1 January 1993). Sociology in Europe: In Search of Identity. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-3-1101-3845-0.

- ^ Bernhard, Michael; Szlajfer, Henryk (1 November 2010). From the Polish Underground: Selections from Krytyka, 1978–1993. Penn State Press. pp. 221–. ISBN 978-0-2710-4427-9.

- ^ Luciano, Bernadette (2008). Cinema of Silvio Soldini: Dream, Image, Voyage. Troubador. pp. 77ff. ISBN 978-1-9065-1024-4.

- ^ Grofman, Bernard (2001). Political Science as Puzzle Solving. University of Michigan Press. pp. 85ff. ISBN 0-4720-8723-1.

- ^ Sadurski, Wojciech; Czarnota, Adam; Krygier, Martin (30 July 2006). Spreading Democracy and the Rule of Law?: The Impact of EU Enlargemente for the Rule of Law, Democracy and Constitutionalism in Post-Communist Legal Orders. Springer. pp. 285–. ISBN 978-1-4020-3842-6.

- ^ Putz, Catherine (16 December 2016). "1986: Kazakhstan's Other Independence Anniversary". The Diplomat. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Yakubova, Aiten (6 April 2020). "Collapse of the Soviet Union: National Conflicts and Independence". Socialist Alternative.

- ^ "Constitutional Instability in Ukraine Leads to 'Legal Turmoil'".

- ^ Antohi, Sorin; Tismăneanu, Vladimir (January 2000). "Independence Reborn and the Demons of the Velvet Revolution". Between Past and Future: The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Aftermath. Central European University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9-6391-1671-8.

- ^ Boyes, Roger (4 June 2009). "World Agenda: 20 years later, Poland can lead eastern Europe once again". The Times. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (1991). Civil Resistance in the East European and Soviet Revolutions. Albert Einstein Institution. ISBN 1-8808-1304-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2011.

- ^ Sztompka, Piotr (27 August 1991). "Preface". Society in Action: the Theory of Social Becoming. University of Chicago Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-2267-8815-6.

- ^ "Yugoslavia". Constitution. Greece: CECL. 27 April 1992. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ Yoon, Dae-kyu (2003). "The Constitution of North Korea: Its Changes and Implications". Fordham International Law Journal. 27.

- ^ "A Day That Shook The World: Cold War officially ends". The Independent. 3 December 2010.

- ^ Service, Robert (2015). The End of the Cold War: 1985–1991. Macmillan.

- ^ Findlay, Trevor (1995). Cambodia: the legacy and lessons of UNTAC (reprinted 1997 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 0-1982-9185-X.

- ^ Kenney, Padraic (2006). The Burdens of Freedom: Eastern Europe Since 1989. pp. 3, 57.

- ^ Glazer, Sarah (27 August 2004). "Stopping Genocide". CQ Researcher. 14 (29): 685–708.

- ^ "Sinclair Research website". Archived from the original on 2014-12-14. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (November 2, 2009). "Personal Computer Market Share: 1975–2004". Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (December 2, 2012). "Personal Computer Market Share: 1975–2004". Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ^ CASS, STEPHEN (2023). "Hands On Yugoslavia's Home-Brewed Microcomputer". IEEE Spectrum. 60 (8): 16–18.

- ^ "Computing Japan". Computing Japan. 54–59: 18. 1999. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

...its venerable PC 9800 series, which has sold more than 18 million units over the years, and is the reason why NEC has been the number one PC vendor in Japan for as long as anyone can remember.

- ^ Polsson, Ken. "Chronology of Amiga Computers". Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ "A Decade of Personal Computing". Information Week. 5 August 1991. p. 24.

- ^ Angler, Martin. "Obituary: The PC is Dead". JACKED IN. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Bull, Michael (2006). "Investigating the Culture of Mobile Listening: From Walkman to iPod". Consuming Music Together. Computer Supported Cooperative Work. 35: 131–149. doi:10.1007/1-4020-4097-0_7. ISBN 1-4020-4031-8.

- ^ Du Gay, Paul (1997). Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9780761954026.

- ^ "Sony Announces Two New Premium High-End Digital Audio Players". Forbes.

- ^ Batey, Mark (2016), Brand Meaning: Meaning, Myth and Mystique in Today's Brands (Second ed.), Routledge, p. 140

- ^ a b 株式会社インプレス (2010-10-22). "ソニー、カセット型ウォークマンの生産・販売終了". AV Watch (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- ^ "Sony's modern take on the iconic Walkman". The Hindu BusinessLine. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ "Sony History". Sony Electronics Inc. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ "Philips N1500, N1700 and V2000 systems". Rewind Museum. Vision International. 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ Sun, Yazhou; Yan, Sophia (2016-07-22). "The last VCR will be manufactured this month". CNNMoney. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ "Welcome to nginx". Archived from the original on 2013-01-02. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ^ Riedel, Bruce (2012). "Foreword". Becoming Enemies: U.S.–Iran Relations and the Iran–Iraq War, 1979–1988. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. ix. ISBN 978-1-4422-0830-8.

The Iran–Iraq War was devastating—one of the largest and longest conventional interstate wars since the Korean conflict ended in 1953. A half million lives were lost, perhaps another million were injured, and the economic cost was over a trillion dollars. ... the battle lines at the end of the war were almost exactly where they were at the beginning of hostilities. It was also the only war in modern times in which chemical weapons were used on a massive scale. ... The Iranians call the war the 'imposed war' because they believe the United States imposed it on them and orchestrated the global 'tilt' toward Iraq in the war.

- ^ Gölz, "Martyrdom and Masculinity in Warring Iran. The Karbala Paradigm, the Heroic, and the Personal Dimensions of War." Archived 17 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Behemoth 12, no. 1 (2019): 35–51, 35.

- ^ "Deng Xiaoping". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Deng Xiaoping". Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. (US) and "Deng Xiaoping". Oxford UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Teng Hsiao-p'ing". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Mao's last hurrah: the campaign against Teng Hsiao-Ping" (PDF). CIA. August 1976. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2021.

- ^ Faison, Seth (20 February 1997). "Deng Xiaoping is Dead at 92; Architect of Modern China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Deng Xiaoping: Architect of modern China". China Daily. 2014. Archived from the original on 23 June 2024.

- ^ Vogel 2011.

- ^ Denmark, Abraham. "40 years ago, Deng Xiaoping changed China — and the world". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Man of the Year: Teng Hsiao-p'ing: Visions of a New China". Time. 1 January 1979. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Man of the Year: Deng Xiaoping". Time. 6 January 1986. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Wu, Wei (4 June 2015). "Why China's Political Reforms Failed". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Denmark, Abraham. "40 years ago, Deng Xiaoping changed China — and the world". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini calls on Muslims to kill Salman Rushdie, author of "The Satanic Verses" | February 14, 1989". HISTORY. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ "The ten largest gatherings in human history". The Telegraph. 2015-01-19. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ "Which Famous Figure Had the Biggest Public Funeral?". HISTORY. 2018-08-29. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ "Article 514 of the Islamic Penal Code".

- ^ "Iranian Revolution | Summary, Causes, Effects, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-10-26. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ Overton, Iain (2019-04-13). "How a 13-year-old boy became the first modern suicide bomber". British GQ. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ Fard, Erfan (2021-04-16). "Antisemitism Is Inseparable from Khomeinism". Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ The Week UK (2024-02-17). "Iran and the 'Great Satan'". theweek. Retrieved 2024-12-10.

- ^ Shewchuk, Blair (February 2003). "Saddam or Mr. Hussein?". CBC News.

This brings us to the first, and primary, reason many newsrooms use 'Saddam' – it's how he's known throughout Iraq and the rest of the Middle East.

- ^ a b Notzon, Beth; Nesom, Gayle (February 2005). "The Arabic Naming System" (PDF). Science Editor. 28 (1): 20–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2022.

- ^ Burns, John F. (2 July 2004). "Defiant Hussein Rebukes Iraqi Court for Trying Him". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 July 2004.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein". Encyclopædia Britannica. 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim; Rautsi, Inari (2002). Saddam Hussein: A Political Biography. Grove Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8021-3978-8.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Mitterrand". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "François Mitterrand". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Chambers, Mortimer (2010). The Western Experience (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-07-729117-4. OCLC 320804011. [page needed]

- ^ "Late German Chancellor Helmut Kohl to be honored with special European commemoration – News – DW – 18.06.2017". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Bush, George H. W. (13 November 2006). "60 Years of Heroes: Helmut Kohl". Time Europe. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "Clinton Praises Germany's Kohl at Berlin Award". Monsters and Critics. Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 16 May 2011. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Gorbachev" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "Gorbachev, Mikhail" Archived 13 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 4 February 2019

- ^ "Gorbachev". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Campbell, Beatrix (2015), "Margaret Thatcher: To be or not to be a woman", British Politics, 10 (1): 41–51, doi:10.1057/bp.2014.27, S2CID 143944033

- ^ Marsh, David (1991), "Privatization under Mrs. Thatcher: a review of the literature", Public Administration, 69 (4): 459–480, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00915.x

- ^ Dorey, Peter (2016), "Weakening the Trade Unions, One Step at a Time: The Thatcher Governments' Strategy for the Reform of Trade-Union Law, 1979–1984" (PDF), Historical Studies in Industrial Relations, 37: 169–200, doi:10.3828/hsir.2016.37.6[dead link]

- ^ Evans, Eric J. (2018), Thatcher and Thatcherism (fourth ed.), Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-429-89275-2

- ^ Brown, Archie (2020), The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan, and Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War, OUP Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-106561-3

- ^ Evans, Eric J. (2004), Thatcher and Thatcherism (reprint, revised ed.), Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0-415-27013-7

- ^ Quoted in "In Their Own Words: Obama on Reagan," New York Times

- ^ "Governo Sarney. A Economia no Governo Sarney". Brasil Escola (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ "Plano Cruzado - o que foi, congelamento de preços, 1986, resumo". www.suapesquisa.com. 2019-02-14. Archived from the original on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ "Plano Cruzado". Memória Globo. 2009-04-13. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ^ "Plano Verão completa 21 anos neste sábado - Economês - Virgula". virgula.uol.com.br. 2010-07-28. Archived from the original on 2010-07-28. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

Sources

[edit]- Vogel, Ezra F. (2011). Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05544-5.